Abstract

Background:

Parkinson’s disease (PD) eventually leads to severe functional decline and dependence. Specialized care units for PD patients in need of permanent care are lacking.

Methods:

Patients with severe PD are referred to the PD permanent care unit harboring 30 patients with specialized medical and health care provided by trained staff. Patients need to have intensive medical and care needs, and be no longer able to stay at home or at an ordinary institution. A written and continuously reviewed care plan is made for each patient at admission, with the overriding aim to preserve quality of life and optimize functionality.

Results:

After five years, the PD permanent care unit has cared for 70 patients (36 men and 34 women) with a mean age of 76.6 years and a mean duration of Parkinsonism of 11.8 years. Hoehn and Yahr severity of disease was 3.7, cognition was 25.3 (Mini-Mental State Examination), and the mean daily levodopa dose was 739 mg. The yearly fatality rate was seven, and the mean duration of stay was 26.9 months. Only five patients moved out from the unit.

Conclusion:

A specially designed and staffed care unit for Parkinsonism patients seems to fill a need for patients and caregivers, as well as for social and health care authorities. This model is sensitive to the changing needs and capacities of patients, ensuring that appropriate services are available in a timely manner. There was a rather short duration of patient stay and remaining life span after admission to the unit. Despite the chronic/palliative state of patients at the PD permanent care unit, there are many therapeutic options, with the overriding objective being to allow the patients to end their days in a professional and comfortable environment.

Introduction

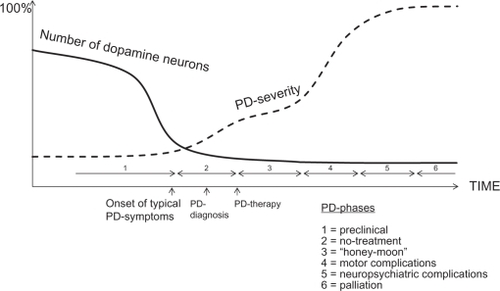

The most common neurodegenerative movement disorder is Parkinson’s disease (PD), eventually leading to severe functional decline and dependence.Citation1 During disease progression, patients develop not only motor complications, like fluctuations and dyskinesia, but also nonmotor symptoms from many organs.Citation2,Citation3 These nonmotor symptoms are those that do not traditionally count as PD symptoms, but are receiving more interest in recent years because PD today is recognized as a multisystem brain disorder. The longer the duration of disease, the more the accumulation of these symptoms, which are often more devastating to patients than the motor symptoms. Neuropsychiatric symptoms like nightmares, paranoid ideas, hallucinations, and, ultimately, psychosis, often accompanied by cognitive decline, may appear.Citation4 These symptoms are often very troublesome to the patient as well as to the caregiver, and are sometimes so difficult to treat and cope with, that affected patients are eventually institutionalized.Citation5 This occurs even if the patients have devoted caregivers, as well as formal home help services.

From disease onset and/or diagnosis, most patients are treated and cared for at outpatient departments. However, with PD being a progressive disorder, the worsening of and onset of new symptoms increases the need for outpatient visits, temporary hospital stays, home help, and respite care. It is evident that PD patients, unlike many other vulnerable patient groups, eg, those with Alzheimer’s disease or stroke, are often excluded from permanent stay in special care units. Such a unit could be an appropriate site when the disease is at an end-stage and palliative phase, the caregivers are no longer able to care for the patient, and more home help is not possible or adequate. This should be appropriate because the view of palliative care is now broader, and includes care for those patients in whom the consequences of their illness require treatment, regardless of the prognosis of the patient.Citation6 Thus, palliation is not the same as end-of-life care, care targeted for cancer patients, or patients with a bad prognosis. When it comes to complex neurodegenerative diseases like PD, it is difficult to use prognosis estimates as determining factors for referrals to palliative care,Citation7 and even if there is a need for palliative care for a PD patient, such care is poorly developed.Citation8

Therefore, there was a need for patients, caregivers, patient organizations, and social authorities to organize a special care unit for PD patients in need of permanent care with specially trained and interested staff. Such a specialized PD care unit for permanent stay was launched in 2004 and, to our knowledge, no such unit was then currently existing in Europe. The organization and launching of the unit was preceded by negotiations and agreements between local health and social care authorities, a housing company, and the Swedish Parkinson Disease Organization leading to joint liability for lodging, caring, and medical health services. We report here the general design, implementation, and results since starting five years ago.

Methods

The Parkinsonism permanent care unit is situated in the center of Täby, a suburb of Stockholm. Patients with a diagnosis of Parkinsonism living within the Stockholm catchment area of about 2,020,000 inhabitants are eligible to be referred to the unit. Referred patients are carefully assessed by two specially trained nurses, as well as representatives from the Stockholm social care authorities, in order to assess the patient’s needs and grant a permit for permanent care for the patient before admission. Referrals are issued by physicians or representatives of social care authorities with the prerequisite that the patient has intense medical and caring needs and, due to these, is no longer able to stay at home or at an ordinary nursing home. Patients with severe psychotic or behavioral symptoms making it impossible to stay within the unit and those at risk of hurting others are the only ones who are ineligible.

The PD permanent care unit houses 30 patients, all in their own rooms with options to do their own furnishing. There are shared dining and living rooms, as well as training facilities within the unit. Patients have their meals together at regular times, with the option for patients to assist the staff in meal preparation in order to maintain normal activities of daily living as far as possible.

The staff comprises two nurses and ten assistant nurses during the day time, six assistant nurses in the evenings until 10 pm, and two at night time. A physician, ie, a movement disorder specialist, visits the PD permanent care unit every fourth week and then, according to a preset schedule, assesses ten patients each time, as well as on request. There is also a geriatrician who visits the PD permanent care unit weekly, taking care of general medical problems. Moreover, an occupational therapist and a physiotherapist work part-time on a daily basis at the unit. Before the opening of the PD permanent care unit, the staff had been carefully selected and then educated for six weeks regarding symptomatology, treatment, and care of PD.

A written and continuously reviewed care plan with a multidisciplinary approach is made for each patient at admission. This includes recognition of the patient’s medical and care status, as well as their social, emotional, cultural, and spiritual needs. It also means determining and regularly assessing these, and whether the PD permanent care unit is the appropriate site of care. Severity of disease is measured by Hoehn and YahrCitation9 and cognition by Mini-Mental State Examination. Citation10 Hoehn and Yahr is an ordinal scale categorizing the severity of PD from 0 to 5, where 0 represents mild disease and 5 very severe disease. All services aim to preserve the patient’s quality of life and optimize functionality as much as possible, as well as to alleviate problematic symptoms whatever their cause, with a supporting and comforting attitude from caring staff. Physical, mental, and emotional changes in the patient are handled at the PD permanent care unit as much as possible, with the possibility of a temporary transfer to hospital if there are other illnesses demanding specialized investigations or treatments. However, patients are to be readmitted to the PD permanent care unit after the acute phase is over.

Common nonmotor symptoms are handled individually, guided by a special treatment protocol ().Citation11 In addition to the risk of developing or having cognitive failure, another common and pervasive complication in late-stage PD is postural instability. This may create a fear of falling, resulting in dependency and immobilization, which might increase the risk of constipation and osteoporosis.Citation11 Physiotherapy and exercise to improve gait, balance, joint mobility, and transfers are performed to compensate for debilitating disease progression.Citation12

Table 1 Treatment guide for some nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease

Patients are thoroughly assessed at admission to the PD permanent care unit, and screened with laboratory tests on a yearly basis thereafter, as well as continuously followed up regarding their Parkinsonism, especially their nonmotor symptoms. Weight, appetite, stool, and risk of falls,Citation13 as well as neuropsychiatric problems and sleep, are followed up on a daily basis, with adequate action plans when needed. Family members are also incorporated in the patient’s care planning and regular family meetings are established, thus informing and involving family members and assessing their needs and wishes. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee of Stockholm.

Results

Over a period of five years, the PD permanent care unit has cared for 70 patients (36 men and 34 women) of mean age 76.6 (range 60–90) years at admission. The mean duration of Parkinsonism was 11.8 (range 3–29) years, with a mean Hoehn and Yahr of 3.7 (range 1–5) and a mean Mini-Mental State Examination of 23.8 (range 10–30, see ). Some activities of daily living-dependent factors as surrogate measures of caregiver burden are also depicted in .

Table 2 Characteristics of patients at the Parkinson’s disease permanent care unit 2005–2009

There were 62 patients with a diagnosis of idiopathic PD, three with multiple system atrophy, two with progressive supranuclear palsy, one with corticobasal degeneration, one with dementia with Lewy bodies, and one with vascular-induced Parkinsonism. The initial PD diagnosis was later on reassessed and rediagnosed as multiple system atrophy in two cases and dementia with Lewy bodies in one case. The mean daily levodopa dose was 739 (range 300–1200) mg, with 16 patients having additional therapy with a catechol-O-methyl transferase inhibitor, 14 patients with a monoamine oxidase B inhibitor, 12 patients with a dopamine agonist, one patient with Duodena®, and three with deep brain stimulation. The mean duration of stay was 26.9 (range 1–58) months, where five patients moved out from the PD permanent care unit for social reasons after a mean length of stay of six (range 1–13) months. There were 13 acute transfers to hospital due to exacerbation or new onset of comorbidity, but none due to Parkinsonism per se. The mean annual fatality rate was seven (range 5–8) with pneumonia as the most common cause of death. There were no significant gender differences for the parameters described (). During the last three years, there has been a waiting list for admission of 2.5 months.

Discussion

A specially designed and staffed care unit, exclusively for patients with Parkinsonism, appears to fill a need for both patients and caregivers, as well as for social and health care authorities. Patients are in a complicated chronic/palliative state of their disease, which is a prerequisite for being referred and accepted to the PD permanent care unit. They are mostly elderly patients, with a PD duration of more than ten years, and a rather high caregiver burden, as reflected by high Hoehn and Yahr scores, a high number of neuropsychiatric symptoms and medications, and a need for help in activities of daily living, as indicated by the need for a wheelchair and help with feeding (see ).

Parkinsonism was the inclusion criterion, and not only that arising from idiopathic PD, because the need for and approach to treatment would be the same for all affected patients. However, the majority of our patients had a diagnosis of idiopathic PD. Only a few patients have been permanently discharged from the unit during the first five years of the unit’s operation, and those who actually moved out from the PD permanent care unit did so for social and not medical reasons, mostly in order to be closer to their relatives. However, the vast majority of patients remained at the unit until the end of their lives. Surprisingly, there was a rather short duration of stay and remaining life span for these patients after admission to the unit, despite the fact that they had had Parkinsonism for about ten years, but were now in a severe stage of disease. Not unexpectedly, the patients deteriorated during their stay, having more severe symptoms as well as concomitant diseases. Other studies have highlighted the complications experienced by PD patients and pointed out strategies to maintain symptom control in late-stage PD.Citation14,Citation15 Even cognitive behavior therapy has been tried in PD patients suffering from nonmotor symptoms like depression, fatigue, sleep disturbances, or pain, but there are no conclusive results of its effectiveness.Citation16 However, to our knowledge, there is no such unit as the one described in this paper.

We believe that patients with end-stage Parkinsonism and their caregivers are confronted with similar problems and needs as those with typical palliative diagnoses, like cancer.Citation17 However, patients often do not want to identify themselves as having a terminal illness with a limited lifespan.Citation18 In general, disease survival in PD patients differs between studies. One study showed a two-fold increased risk of death, with a mean age at death of 82 years,Citation19,Citation20 and another study demonstrated survival of PD patients to be similar to that in a control population, up to a disease duration of ten years.Citation21 After ten years, these rates were followed by a rise in mortality, which could explain our figures. It has been shown that, in PD patients reaching Hoehn and Yahr Stage III, as in our patients, the patient’s survival time is limited.Citation22

The multidisciplinary palliation approach performed by our staff is probably beneficial to patients and their caregivers, as indicated by the low discharge rate of patients from the unit. It has also earlier been described that non-neurologically educated health care personnel are unfamiliar with PD.Citation23

The well-trained, specialized staff may also temper the impact of disease because there have been no acute transfers to hospital due to Parkinsonism. A recent study has reported that one-third of PD patients are dissatisfied with the way their PD was managed during an acute hospital stay.Citation24 In contrast, that study also showed that PD patients are hospitalized in frequencies ranging from 7% to 29% per year, and that a substantial number of admissions may be prevented. In our PD permanent care unit it seems that the number of places is adequate with regard to demand, as indicated by the small waiting list.

The PD permanent care unit’s work contrasts with that performed by families, which is categorized as a simple caring role with adjunctive professional services regularly or on demand. The content of the PD permanent care unit is more of complex care, continuously under surveillance by trained health care professionals, and also often involving advanced medical tasks in accordance with the concept of stroke units.Citation25 Another study has emphasized that the nature of the disease will test the skills and coping abilities of everyone involved when caring for the PD patient.Citation26 Clinical competence, commitment, and communication are three crucial parameters of the work process at the PD permanent care unit. This includes confirmation of diagnosis through medical records and ad hoc complementary investigations. The emphasis of the services is on quality of life. Individual and regular assessment of patients, with goal setting and follow-up, is crucial, as is the integration of family members into the caring process. A constant readjustment to a changing level of ability of the patient is important for the Parkinsonism patient. During the course of the disease, nutritional requirements often change, resulting in body weight gain or loss, which make a regular nutritional assessment important because it may affect the patient’s quality of life.Citation27 Moreover, common problem areas are well considered and handled, including careful observation for potentially contraindicated drugs, exact timing or even temporary cessation of drug administration, monitoring of complications due to immobilization, as well as monitoring of emerging psychiatric and cognitive dysfunction.

A limitation of our study is that we did not assess the impact of the PD permanent care unit on caregivers, ie, if they felt supported and/or relieved that their loved one’s care was better. Moreover, we have no data on the health economic aspects of this model, ie, if it is cost-beneficial compared with traditional alternatives, like home care or care in a nonspecialized unit.

It is reasonable to believe that when patients are transferred from home to the PD permanent care unit, many aspects of caregiver burden are relieved. These include the physical, emotional, and social impact on caregivers, as well as the common limitations of personal time, eventually leading to decreased life space.Citation28 It has been reported that caregiver burden increases with increasing disability and disease duration.Citation29,Citation30 The PD permanent care unit may therefore function as a relief of responsibilities for caregivers, although they are a valuable source of communication and are also very familiar with the patient and can help to identify the patient’s needs.Citation31 This is especially important for PD patients, because the symptoms of PD can vary widely between doses of medication and the side effects can be complex to manage.

Meeting all the needs of patients with Parkinsonism in a chronic/palliative state is an important aim of the PD permanent care unit. Despite the chronic/palliative state of these patients, there are many therapeutic options, with the overriding objective to let the patients end their days in a professional and comfortable environment. Future studies should include assessment of patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life and the impact on caregivers’ life. A health-economic calculation, including the costs of caregivers, should also be integrated in such a study.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all staff members and especially the two nurses, Birgitta Wiklund and Lena Hultgren, of the PD permanent care unit who performed many of the assessments and provided much of the data.

Disclosure

The study was not supported by any monetary grants. The author has no connections with the pharmaceutical industry or stock companies which could be considered to be potential areas of conflict.

References

- MaetzlerWLiepeltIBergDProgression of Parkinson’s disease in the clinical phase: Potential markersLancet Neurol200981158117119909914

- ChaudhuriKRSchapiraAHNon-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: Dopaminergic pathophysiology and treatmentLancet Neurol2009846447419375664

- PoeweWClinical measures of progression in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord200924Suppl 2S671S67619877235

- AarslandDMarschLSchragANeuropsychiatric symptoms in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord2009242175218619768724

- AarslandDLarsenJPTandbergELaakeKPredictors of nursing home placement in Parkinson’s disease: A population-based prospective studyJ Am Geriatr Soc20004893894210968298

- LanoixMPalliative care and Parkinson’s disease: Managing the chronic-palliative interfaceChronic Illn20095465519276225

- ChristakisNLamontEExtent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective study cohortBMJ200032046947310678857

- CloughCGBlockleyAPalliative care for Parkinson’sVoltzRBernatJLBorasioGDMaddocksIOliverDPortenoyRKPalliative Care in NeurologyNew YorkOxford University Press2004

- HoehnMMYahrMDParkinsonism: Onset, progression and mortalityNeurology1967174274426067254

- CockrellJRFolsteinMFMini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)Psychopharmacol Bull1988246896923249771

- LeesAJHardyJRevesczTParkinson’s diseaseLancet20093732055206619524782

- KeusSHBloemBRHendriksEJEvidence-based analysis of physical therapy in Parkinson’s disease with recommendations for practice and researchMov Disord20072245146017133526

- DowntonJHAndrewsKPrevalence, characteristics and factors associated with falls among the elderly living at homeAging199132192281764490

- WatersCHTreatment of advanced stage patients with Parkinson’s diseaseParkinsonism Relat Disord20029152112217618

- RockwoodKSyoleePMcDowellIFactors associated with institutionalization of older people in Canada: Testing a multifactorial definition of frailtyJ Am Geriatric Soc1996144578582

- MallickSPalliative care in Parkinson’s disease: Role of cognitive behavior therapyIndian J Palliat Care200915515620606856

- HudsonPLToyeCKristjansonLJWould people with Parkinson’s disease benefit from palliative care?Palliat Med200620879416613404

- HudsonPLElmanLBHoughtonDJPalliative care in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosisJ Palliat Med20071043345717472516

- MorganteLSalemiGMeneghiniFParkinson disease survival: A population-based studyArch Neurol20005750751210768625

- FallPASalehAFredricksonMOlssonGranérusAKSurvival time, mortality, and cause of death in elderly patients with Parkinson’s disease: A 9-year follow-upMov Disord2003181312131614639673

- Diem-ZanglerASeppiKWenningGMortality in Parkinson’s disease: A 20-year follow-up studyMov Disord20092481982519224612

- RoosRAJongenJCvan der VeldeEAClinical course of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord1996112362428723138

- MartignoniEGodiLCitterioAComorbid disorders and hospitalization in Parkinson’s disease: A prospective studyNeurol Sci200425667115221624

- GerlachOWinogrodzkaAWeberWClinical problems in the hospitalized Parkinson’s disease patient: Systematic reviewMov Disord1312011 [Epub ahead of print]

- Bunting-PerryLKPalliative care in Parkinson’s disease: Implications for neuroscience nursingJ Neurosci Nurs20063810611316681291

- VergenzSCaring for the Parkinson’s patient: A nurse’s perspectiveDis Mon20075324325117586331

- BarichellaMCeredaEPezzoliGMajor nutritional issues in the management of Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord2009241881189219691125

- LökkJReduced life-space of non-professional caregivers to Parkinson’s disease patients with increased disease durationClin Neurol Neurosurg200911158358719559520

- SchragAMoreyDQuinnNJahanshahiMImpact of Parkinson’s disease on patients’ adolescent and adult childrenParkinsonism Relat Disord20041039139715465394

- LökkJCaregiver strain in Parkinson’s disease and the impact of disease durationEur J Phys Rehabil Med200844394518385627

- GoyERCarterJHGanziniLParkinson’s disease at end of life: Caregiver perspectivesNeurology20076961161217679683