Abstract

Cardiac auscultation – even with its limitations – is still a valid and economical technique for the diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases, and despite the growing demand for sophisticated imaging techniques, clinical use of the stethoscope in medical practice has not yet been abandoned. In 1816, René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laënnec invented the stethoscope, while examining a young woman with suspected heart disease, giving rise to mediated auscultation. He described in detail several heart and lung sounds, correlating them with postmortem pathology. Even today, a correct interpretation of heart sounds, integrated with the clinical history and physical examination, allows to detect properly most of the structural heart abnormalities or to evaluate them in a differential diagnosis. However, the lack of organic teaching of auscultation and its inadequate practice have a negative impact on the clinical competence of physicians in training, also reflecting a diminished academic interest in physical semiotic. Medical simulation could be an effective instructional tool in teaching and deepening auscultation. Handheld ultrasound devices could be used for screening or for integrating and improving auscultatory abilities of physicians; the electronic stethoscope, with its new digital capabilities, will help to achieve a correct diagnosis. The availability of innovative representations of the sounds with phono- and spectrograms provides an important aid in diagnosis, in teaching practice and pedagogy. Technological innovations, despite their undoubted value, must complement and not supplant a complete physical examination; clinical auscultation remains an important and cost-effective screening method for the physicians in cardiorespiratory diagnosis. Cardiac auscultation has a future, and the stethoscope has not yet become a medical heirloom.

Introduction

For over 200 years, cardiac auscultation has been the cornerstone of the clinical approach to the cardiac patient and is still used in medical practice.

Auscultation – empirically used since ancient times – entered as a method of semeiotic survey only at the dawn of the 19th century, thanks to the French physician René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laënnec(1781–1826), the inventor of the stethoscope, who defined and interpreted most of the acoustic phenomena.Citation1 The stethoscope, since then, was used as an essential tool for cardiovascular evaluation.

Two hundred years ago, in February 1818, Laënnec presented the discovery and potential application of his stethoscope at the Paris Academy of Sciences and in 1819 published the work De l’auscultation médiate or Traité du Diagnostic des Maladies des Poumon et du Coeur, in two volumesCitation1 ().

Figure 1 Laënnec’s masterpiece, entitled De l’auscultation médiate ou Traité du Diagnostic des Maladies des Poumonet du Coeur [A treatise on the diseases of the chest and on mediate auscultation], 1819.

![Figure 1 Laënnec’s masterpiece, entitled De l’auscultation médiate ou Traité du Diagnostic des Maladies des Poumonet du Coeur [A treatise on the diseases of the chest and on mediate auscultation], 1819.](/cms/asset/29da9edd-9b0b-4a8b-820e-d96859224e8f/djmd_a_193904_f0001_c.jpg)

Heart auscultation is a routine procedure that provides important clinical-prognostic information and should guide especially general practitioners in proposing further instrumental examinations. However, the decrease of rheumatic valvular disease and the widespread availability of new diagnostic methods of cardiac imaging (in particular, Doppler echocardiography) have reduced the importance of the diagnostic value of auscultation. Nowadays, it is poorly taught, neglected, or improperly performed, with consequent inaccurate and incomplete patient assessments.Citation2–Citation4

Nevertheless, auscultation – even with its limitations – remains an important, cost-effective, and widespread approach to a preliminary clinical evaluation by the physician.

Historical perspective

Since the days of Hippocrates (c.460–c.370 BC), physicians performed auscultation of lung and heart sounds by placing their ear directly on the patient’s chest, a technique called “immediate auscultation”. The succussion splash of hydro- pneumothorax was one of the first thoracic sounds described by Hippocrates.Citation5,Citation6 He also described the friction rub of pleuritis (“a creak like new leather”) and other types of medical sounds.Citation5 Instead, the heart sounds, though they must have been auscultated, were never discussed before William Harvey.

Also, the Roman physician Caelius Aurelianus (fifth century AD), Leonardo Da Vinci (1452–1519), Ambroise Paré (1510–1590), Giovan Battista Morgagni (1682–1771), Gerhard Van Swieten (1700–1772), and others became interested in cardiac auscultation.

In 1628, William Harvey (1578–1657) first treated heart sounds in De Motu Cordis: “With each movement of the heart, when there is the delivery of a quantity of blood from the veins to the arteries, a pulse takes place and can be heard within the chest”.Citation7 Harvey, in his “visceral lectures” of 1616, compared heart sounds to “two clacks of a water bellows to rayse water.”Citation8

Robert Hooke (1635–1703) – secretary of the Royal Society of London, best known for Hooke’s Law – was familiar with heart sounds and predicted the utility of auscultation.Citation9

In 1715, James Douglas (1675–1742), fellow of the Royal Society of London, heard severe aortic regurgitation murmur at some distance from the patient’s bedside.Citation10

In 1757, William Hunter (1718–1783), professor of Anatomy to the Royal Academy, London, described a thrill (“particular vibratory movement”) and a murmur (“bruissement”) of arteriovenous fistula.Citation11

Jean-Nicholas Corvisart (1755–1821), one of Laënnec’s teachers and physician to Napoleon, suggested the possibility of using the sounds coming from the internal organs to diagnose diseases.Citation9

Allan Burns (1781–1813), cardiologist and lecturer on anatomy and surgery at Glasgow, described the heart murmurs clearly and in detail.Citation9

Gaspard-Laurent Bayle (1774–1816) taught Laënnec direct auscultation, but the pupil found the technique uncomfortable and often embarrassing, especially to females.

Immediate auscultation was a useful method for examining the respiratory system, since the ear direct application to the chest allowed auscultation of a large lung area. Instead, it was not equally appropriate for cardiac examination, as it was unfit to locate heart sounds coming from small and circumscribed precordial zones.

But above all, it was essential to meet the needs of decency, hygiene, and opportunity: it was embarrassing to perform immediate auscultation on young women and it was generally difficult to perceive and interpret paraphonic sounds of obese patients.

Precisely, during a medical examination of a young woman who presented the general symptoms of heart disease, Laënnec had a brilliant idea for chest auscultation. In order to avoid the embarrassment caused by placing his ear on the girl’s breasts, he tightly rolled a sheet of paper into a cylinder and applied one end to the woman’s chest and the other to his ear. According to him, “was not a little surprised and pleased to find that I could thereby perceive the action of the heart in a manner much more clear and distinct than I had ever been able to do by the immediate application of my ear.”Citation6,Citation12

In the following three years, Laënnec experimented with various materials to make the tube and finally decided for a 25-by-2.5-cm hollow wooden cylinder. The instrument was subsequently improved into a more functional portable device, with three detachable cylinders. Thus the stethoscope was born, the first medical instrument that allowed “mediated auscultation”. The word stethoscope derives from the Greek stethos=chest and scopein=to examine; “auscultation” was a word coined by Laënnec himself, derived from the Latin auscultare, meaning to listen carefully, and not simply to listen; “Mediate” implied that the auscultation was not direct, but mediated by the tube.

Laënnec studied with his stethoscope cardiac and pulmonary sounds of about 3,000 patients, correlating his antemortem observations with the autopsy findings.

In February 1818, he presented the results of his research at the Académie de médecine, and, in 1819, published the first edition of his masterpiece in two volumes De l’auscultation médiate ou Traité du Diagnostic des Maladies des Poumon et du Coeur,Citation1 of which more than 3,500 copies were printed. John Forbes (1787–1861) published an English translation of the treatise in London in 1821 and in Philadelphia in 1823.Citation6 The German translation of the work was made in 1822 and the Italian translation in 1833. In 1826 a second revised edition of the treatise was published, with masterly discussion on the correlation between stetoacoustic findings and autopsy data.

Laënnec coined the terms – which appeared for the first time in his work and are still used today – rhonchi, rales, crepitance, egophony, bronchophony, pectoriloquy, to describe the thoracic acoustic findings that he had auscultated (). He erroneously attributed S1 to ventricular systole and S2 to atrial systole, rather than the closing of the atrioventricular valves and aortic and pulmonary semilunar valves, respectively.

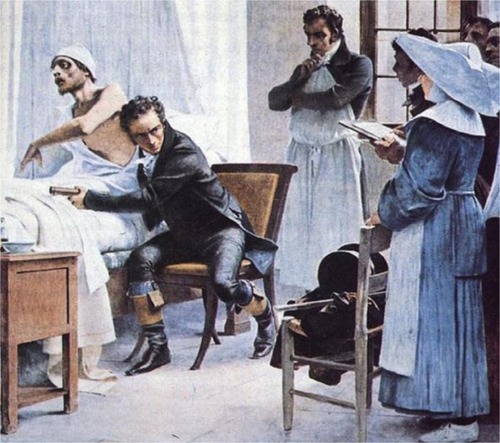

Figure 2 Laënnec at the bedside performing direct auscultation.

After the publication of his treatise, Laënnec acquired an important scientific authority: in 1822, he became chair of the College of France, professor of medicine in 1823, and in August 1824, he was made a knight of the Legion of Honor.Citation13

Cardiac auscultation taught by Laënnec was a great success, and in subsequent years became a crucial component of cardiac physical examination, especially in times of important diffusion of rheumatic valvulopathies. The study of related heart sounds thus became extremely important for a correct diagnosis and for the clinicopathological correlations of heart disease. As all the major innovations that involve a radical change in daily clinical practice, the stethoscope was initially viewed with skepticism by the scientific community of the time and its extensive use occurred only later. The numerous medical students in Paris spread the new instrument everywhere, as many physicians went to Paris from around the world to learn auscultation directly from Laënnec.

Laënnec’s invention marked an epochal turning point, greatly improving the diagnostic possibilities with clinical examination. His discovery was considerably influenced by French clinical empiricism, by the studies of Ippolito Francesco Albertini, Giovan Battista Morgagni, Leopold Auenbrugger, and Jean-Nicholas Corvisart, and it was the natural evolution of the new clinicopathological method they introduced, based on bedside examination and pathologic anatomy, and contrary to speculative clinical philosophy.

Thus, the stethoscope represented the new scientific and clinical tool that miraculously allowed the physician to transform the sounds he heard into an image he could see.

In the following years, considerable improvements were made to Laënnec’s stethoscope, always based on the original principles of his instrument. In 1851, Arthur Leared (1822–1879) invented a binaural stethoscope with two ear pieces,Citation14 and in 1852, George Philip Cammann (1804–1863) perfected the design of the stethoscope for commercial production, that then became the standard.Citation15

Several stethoscopes were subsequently realized with weight and design improvements (using flexible rubber tubes) and equipped with a bell for the auscultation of the low tone sounds and the diaphragm, to better listen to the acute sounds.

The simple stethoscope then evolved into a sophisticated digital device.

The present and future

Cardiac auscultation is a technique in which interpretative reliability is achieved only after long, patient, and careful clinical exercise: the auscultatory finding should be auscultated hundreds of times before it can be recognized and memorized.

However, the competence in this clinical skill has been greatly reduced in the last decades. Already in 1963, Harold Nathan Segall (1897–1990) hypothesized that in 2016, after 200 years of clinical use, the classic stethoscope would become obsolete and replaced by new electronic systems.Citation16

Reliance on technology for cardiovascular diagnosis seems to have reduced the importance of a thorough physical examination at the bedside, since more accurate diagnostic information can be obtained with more recent instrumental methods. Furthermore, fewer resources are currently being devoted to the teaching and the practice of this technique.Citation2–Citation4

Several works have shown that the current physical examination skills, especially cardiac auscultation, of students and practicing clinicians are surprisingly inadequate, with significant repercussions on patient safety, medical decision-making, and cost-effective care; moreover, acquired auscultatory abilities diminish if they are not exercised enough. This implies the need to improve the teaching and the practice of this important clinical method.Citation2–Citation4,Citation17–Citation20

There is a global decline of general proficiency in physical diagnostic, as shown by a study of internal medicine residents in the United States, Canada, and England, where the correct assessment on auscultation was made in only 22%, 26%, and 20% of patients, respectively.Citation21

Likewise, a study on auscultatory proficiency of pediatric residents in the United States showed a low diagnostic accuracy (30%) and poorly improved with training; those who completed a cardiology rotation improved their ability to diagnose diastolic murmurs of aortic regurgitation and, in particular, the ability to recognize a harmless heart murmur.Citation22

Therefore, on the whole, the sensitivity of cardiac auscultation is low, ranging from 0.21 to 1.00, mainly due to difficulties in the diagnosis of diastolic murmurs; the sensitivity for systolic murmurs alone is better, ranging from 0.67 to 1.00.Citation23

Handheld ultrasound

An important technological innovation is the introduction of pocket-sized handheld ultrasound devices, capable of providing a more accurate diagnosis than cardiac auscultation, in patients with suspected heart disease. In effect, several studies have demonstrated the superiority of this practice defined “point-of-care ultrasound”. This approach would be useful for medical students, doctors in training, general practitioners, and emergency care physicians, which could perform cardiac imaging quality at reduced costs, decreasing additional tests.Citation24–Citation27

This would reaffirm the importance of bedside diagnosis, albeit without a stethoscope, at least for cardiac examination.

Despite the superiority of handheld echocardiography for the detection of many heart abnormalities and the potential use by different operators, expertise in this area requires specific training in both execution and interpretation.Citation28

Furthermore, a randomized parallel group controlled trial with pocket-sized ultrasound as an aid to physical diagnosis had not shown a greater diagnostic accuracy than the traditional physical exam among medicine residents, after a 3-hour training session and 1 month of independent practice, suggesting the need for a longer or more intense training to exploit the diagnostic potential of such devices.Citation29

Similarly, a recent systematic review of handheld ultrasound scanners in medical education showed a lack of consensus on the protocols best suited to the training needs of medical students, on long-term impact and decay in skills.Citation30

Cardiovascular assessment with pocket-sized imaging devices should be considered as an integral part of the patient’s physical examination, without replacing auscultation. These tools should be used for screening or to complement and improve auscultatory abilities, since they – by themselves – do not allow the execution of a complete echocardiographic examination.Citation31

Ultrasound and physical exams are complementary; the peculiar and indispensable purpose of cardiac auscultation is to frame the patient in a clinical setting, in which the echocardiographic findings must also be considered.

New teaching methods, such as auditory training and repetitive listening, facilitate valid identification of murmur and diagnostic learning, and handheld ultrasound can be useful support for teaching auscultation.Citation32

The digital stethoscope

The development of the electronic and digital stethoscopes has ushered in a new era of computer-aided auscultation. The digital stethoscope – made up of three different modules, called data acquisition, preprocessing, and signal processing – transform acoustic sounds into electronic signals, which can be further amplified to optimize auscultation. The subsequent digitalization of the electronic signals allows the transmission of heart sounds to a PC or laptop, for automated analysis, graphic visualization, storage, and archiving.Citation33

Furthermore, several digital stethoscopes can – through Bluetooth connection – transmit heart sounds wirelessly to a remote processing network, promoting the evolution and potential applications of telemedicine.Citation34

Recent studies have suggested the feasibility, in the pre-hospital phase, of a cardiac auscultation of good diagnostic accuracy using smartphones, although the apps used need further improvements.Citation35

This use must be further validated by more in-depth studies and researches.

Digital stethoscope – suppressing ambient noise and friction – allows the doctor to auscultate heart and lung sounds as faithfully as possible to the original; this facilitates more accurate diagnosis based on quantifiable clinical evaluation and thereby promotes better medical care. The possibility of automatic acoustic interpretation opens up intriguing future scenarios not only in cardiovascular diagnostics, but also in enhancing the clinical teaching at the bedside.

Finally, doctors with hearing loss – almost 100% of the practitioner >60 years of age – can benefit from electronic stethoscopes.Citation36

Intelligent phonocardiography – acoustic cardiography

The phonocardiogram is a recording of acoustic waves produced by the mechanical action of the heart, and it was developed in an attempt to provide quantitative and qualitative information of heart sounds and murmurs. The first phonocardiograms resembling modern devices were made by Einthoven and Geluc in 1894,Citation37 and in 1904, Otto Frank first performed recordings of precordial vibrations with optical amplification or direct phonocardiograms.Citation38 In the past, this method was particularly useful to clarify heart sounds having abnormal components: atrial sounds, split sounds, opening snaps, gallop rhythms, clicks, and rubs. The efficiency of phonocardiographic diagnosis has been significantly improved by using modern digital signal processing techniques; the analysis of various signals provides a wide range of statistical parameters and consequently aids diagnosis.Citation39

Several studies have successfully used the discrete wavelet transform in the analysis of pathological severity of aortic and mitral diseases.Citation40 New intelligent computer-aided diagnosis systems (Intelligent Phonocardiography) based on heart sound signal analysis are used to diagnose various heart diseases (atrial fibrillation, aortic regurgitation, mitral regurgitation, normal sound, pulmonary stenosis, ventricular septal defect, pediatric heart diseases, and assessment of aortic valve stenosis).Citation41–Citation43

Acoustic cardiography, a noninvasive and less operator-dependent method, allows the acquisition of detailed information on the systolic and diastolic left ventricular function with a computerized interpretation. It can be used in patients with heart failure, ischemia, and cardiac arrhythmias. Its applications include other diseases, such as sleep apnea, constrictive pericarditis, and left ventricular hypertrophy. It is also a cost-effective and time-efficient tool in heart failure follow-up in both home and hospital settings.Citation44–Citation46

The innovative representations of the sounds with phono- and spectrograms provide an important aid not only in diagnosis, but also in teaching practice and pedagogy.

Conclusion

Clinical auscultation – despite its limits – remains an important and cost-effective screening technique for cardiovascular diagnosis and is still essential for the doctor. A physical examination performed correctly allows to detect properly most of the structural heart abnormalities or to evaluate them in a differential diagnosis. Auscultatory findings provide important prognostic information and guide physicians in recommending appropriate examinations by limiting further expensive tests. Often, excessive specialization leads students and young doctors to overlook the importance of clinical skills and to overemphasize the use of costly high-tech diagnostic methods, reducing their clinical capacity, which should instead remain one of the most important values acquired during the training period.

Simulation-based medical education could be an effective instructional approach for teaching and deepening auscultation. Digital stethoscopes and intelligent phonocardiography can help the doctor to achieve a correct diagnosis, offering further research perspectives in this area. General practitioners are also possible operators of handheld ultrasound devices.

A balanced approach, combining the clinical method with new digital technology to enhance learning and practice, might be the most appropriate procedure to follow.

After 200 years, the stethoscope has not yet become a medical heirloom, and auscultation of the heart should not be considered a lost art.

Key messages are as follow:

In 1816, R.T.H. Laënnec invented the stethoscope and in 1819 published his famous masterpiece De l’auscultation médiate.

Cardiac auscultation is still an important and cost-effective screening method for the physician.

Cardiac auscultation skills are inadequate, probably due to inappropriate use of Doppler echocardiography.

New technological advances such as the electronic stethoscope, handheld ultrasound devices, and simulation-based medical education are a useful support to improve auscultation.

A balanced strategy, combining the clinical method with new digital technology to enhance learning, might be the most appropriate procedure to follow.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- LaënnecRTHDe l’auscultation médiate ou Traité du Diagnostic des Maladies des Poumons et du CoeurA treatise on the diseases of the chest and on mediate auscultationParisChaude1819 French

- MangioneSNiemanLZGracelyEKayeDThe teaching and practice of cardiac auscultation during internal medicine and cardiology training: a nationwide surveyAnn Intern Med1993119147548498764

- MookherjeeSPheattLRanjiSRChouCLPhysical examination education in graduate medical education--a systematic review of the literatureJ Gen Intern Med20132881090109923568186

- MangioneSNiemanLZCardiac auscultatory skills of internal medicine and family practice trainees. A comparison of diagnostic proficiencyJAMA199727897177229286830

- LittréEOeuvres Complètes D’HippocrateHippocrates’s Complete Works7ParisJ. B. Baillère1851 French

- LaënnecRTHA Treatise on the Diseases of the Chest in Which They Are Described According to Their Anatomical Characters and Their DiagnosisForbesJohnLondonT and G Underwood182125

- HarveyWExercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in AnimalibusThe anatomical exercises of Dr William Harvey concerning the motion of the heart and bloodLeakeChauncey DSpringfieldCharles C. Thomas192849 French

- WrightTWilliam Harvey: A Life in CirculationOxfordOxford University Press2012183

- McKusickVACardiovascular Sound in Health and DiseaseBaltimoreWilliams & Wilkins Company1958

- DouglasJAn extraordinary dilatation or enlargement of the left ventricle of the heartTr Roy Soc London1715345181

- HunterWMedical Observations and Researches1764II403

- DuffinJTo See With a Better Eye: A Life of RTH LaennecPrinceton, NJPrinceton University Press1998Reprinted for the Princeton Legacy Library Series2014121141

- JayVThe legacy of LaënnecArch Pathol Lab Med20001241420142111035568

- WilliamsCTLaënnec and the evolution of the stethoscopeBr Med J190726820763351

- PeckPDrCammann and the binaural stethoscopeJ Kans Med Soc19636412112313942295

- SegallHNCardiovascular sound and the stethoscope 1816–2016. The twenty-fifth Louis gross memorial lectureCan Med Assoc J19638830831813987676

- MangioneSThe teaching of cardiac auscultation during internal medicine and family medicine training–a nationwide comparisonAcad Med19987310 SupplS10S129795637

- Vukanovic-CrileyJMCrileySWardeCMCompetency in cardiac examination skills in medical students, trainees, physicians, and faculty: a multicenter studyArch Intern Med2006166661061616567598

- HaringCMCoolsBMvan der MeerJWMPostmaCTStudent performance of the general physical examination in internal medicine: an observational studyBMC Med Educ20141417324712683

- RoelandtJRThe decline of our physical examination skills: is echocardiography to blame?Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging201415324925224282219

- MangioneSCardiac auscultatory skills of physicians-in-training: a comparison of three English-speaking countriesAm J Med2001110321021611182108

- DhuperSVashistSShahNSokalMImprovement of cardiac auscultation skills in pediatric residents with trainingClin Pediatr (Phila)200746323624017416879

- Attenhofer JostCHTurinaJMayerKEchocardiography in the evaluation of systolic murmurs of unknown causeAm J Med200010861462010856408

- MehtaMJacobsonTPetersDHandheld ultrasound versus physical examination in patients referred for transthoracic echocardiography for a suspected cardiac conditionJACC Cardiovasc Imaging201471098399025240450

- PanoulasVFDaigelerALMalaweeraASPocket-size hand-held cardiac ultrasound as an adjunct to clinical examination in the hands of medical students and junior doctorsEur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging201314432333022833550

- KaulSIs it time to replace physical examination with a hand-held ultrasound device?J Cardiovasc Echogr20142449710228465916

- KimuraBJPoint-of-care cardiac ultrasound techniques in the physical examination: better at the bedsideHeart20171031398799428259843

- Chamsi-PashaMASenguptaPPZoghbiWAHandheld echocardiography: current state and future perspectivesCirculation20171362178218829180495

- OjedaJCColbertJALinXPocket-sized ultrasound as an aid to physical diagnosis for internal medicine residents: a randomized trialJ Gen Intern Med201530219920625387438

- GaluskoVKhanjiMYBodgerOWestonCChambersJIonescuAHand-held ultrasound scanners in medical education: a systematic reviewJ Cardiovasc Ultrasound2017253758329093769

- SicariRGalderisiMVoigtJUThe use of pocket-size imaging devices: a position statement of the European association of echocardiographyEur J Echocardiogr2011122858721216764

- BarrettMJMackieASFinleyJPCardiac auscultation in the modern era: premature requiem or phoenix rising?Cardiol Rev201725520521028786895

- LengSTanRSChaiKTWangCGhistaDZhongLThe electronic stethoscopeBiomed Eng Online20151416626159433

- LakheASodhiIWarrierJSinhaVDevelopment of digital stethoscope for telemedicineJ Med Eng Technol2016401202426728637

- KangS-HJoeBYoonYChoG-YShinISuhJ-WCardiac auscultation using Smartphones: pilot studyJMIR Mhealth Uhealth201862e4929490899

- RabinowitzPTaiwoOSircarKAliyuOSladeMPhysician hearing lossAm J Otolaryngol200627182316360818

- EinthovenWGelucMAJDie Registrierung der HerztonePflugers Arch Ges Physiol189457617

- FrankODie Unmittelbare Registrierung Der HerztoneMunchen Med Wochenschr190451593

- ObaidatMSPhonocardiogram signal analysis: techniques and performance comparisonJ Med Eng Technol19931762212278169938

- MezianiFDebbalSMAtbiAAnalysis of the pathological severity degree of aortic stenosis (AS) and mitral stenosis (MS) using the discrete wavelet transform (DWT)J Med Eng Technol2013371617423173773

- SepehriAAKocharianAJananiAGharehbaghiAAn intelligent phonocardiography for automated screening of pediatric heart diseasesJ Med Syst20164011626573653

- GharehbaghiASepehriAALindénMBabicAIntelligent phonocardiography for screening ventricular septal defect using time growing neural networkStud Health Technol Inform201723810811128679899

- GharehbaghiAEkmanIAskPNylanderEJanerot-SjobergBAssessment of aortic valve stenosis severity using intelligent phonocardiographyInt J Cardiol2015198586026151715

- WangSLiuMFangFPrognostic value of acoustic cardiography in patients with chronic heart failureInt J Cardiol201621912112627323336

- ZuberMErnePAcoustic cardiography to improve detection of coronary artery disease with stress testingWorld J Cardiol20102511812421160713

- ErnePResinkTJMuellerAUse of acoustic cardiography immediately following electrical cardioversion to predict relapse of atrial fibrillationJ Atr Fibrillation2017101152729250219