Abstract

Purpose

An important task in primary health care (PHC) is to address lifestyle-related diseases. Overweight (OW) individuals make up a large proportion of PHC patients, and they increasingly have lifestyle-related illnesses that influence their quality of life. Structured health promotion and weight reduction programs could help these patients. The objective of this study was to explore the characteristics, lifestyle habits, and health conditions of individuals seeking a health promotion and weight reduction program in PHC.

Patients and methods

The study involved a comparative cross-sectional design performed in PHC in southwestern Sweden. The study population comprised 286 participants (231 women, aged 40–65 years, body mass index [BMI] 28–35 kg/m2) who were recruited between March 2011 and April 2014 to the 2-year program by adverts in local newspapers and recruitment from three PHC centers. Two reference populations were used: a general population group and an OW group. The study population data were collected using a questionnaire, with validated questions regarding health, lifestyle, illnesses, and health care utilization.

Results

People seeking a health promotion and weight reduction program were mostly women. They had a higher education level and experienced worse general health than the OW population, and they visited PHC more frequently than both reference groups. They also felt more stressed, humiliated, had more body pain, and smoked less compared to the general population. However, they did not exercise less or had a lower intake of fruits and vegetables than either reference population.

Conclusion

Individuals seeking a weight reduction program were mostly women with a higher education level and a worse general health than the OW population. They used more health care services compared to the reference groups.

Introduction

Being overweight (OW; body mass index [BMI] >25 kg/m2) has reached epidemic proportions worldwide, with >1.9 billion OW individuals. The prevalence of obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2) more than doubled between 1980 and 2014, and >600 million individuals were obese in 2014.Citation1 According to an annual report in Sweden, 43% of women and 57% of men were OW.Citation2

OW is associated with negative health implications, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, various forms of cancer,Citation3 psychiatric disorders (eg, depression and anxiety), and many symptoms, such as body pain,Citation4,Citation5 fatigue, and sleeping problems.Citation6 Increasing OW (in terms of increasing BMI) is also associated with worse health-related quality of life among women.Citation7 Many OW individuals in a primary health care (PHC) program for weight reduction also felt more stressed than the general population.Citation8 As a high BMI is associated with many health problems, OW individuals attend general practices more frequently; therefore, it is particularly important to prevent individuals from becoming OW or help them to lose weight by supporting them in adopting a healthy lifestyle.Citation9 Health-related behavior, such as food intake, is also affected by socioeconomic position. Socioeconomically disadvantaged groups have a higher fat intake, a diet lower in fiber, and a lower consumption of fruits and vegetables.Citation10

Personal difficulties occur more frequently among OW individuals, and many report that they are victims of stigmatization, marginalization, and discrimination.Citation11 While external influences on weight, such as environmental factors, are important, it seems that internal factors, such as emotions, are of higher importance.Citation12 However, further research on public attitudes toward and perception of OW is urgently needed to determine the prevailing degree of stigmatization.Citation12 Additionally, weight loss programs have to consider both internal and external factors. Reported weight loss intervention attrition rates vary with individual expectations regarding weight loss.Citation13 Unrealistic weight goals should be dealt with at the beginning of treatment. Individuals who terminate these programs early usually do not receive the support that they need to develop the strategies required for weight loss.Citation14

It is therefore important to determine the characteristics of the population seeking a health promotion and weight reduction program in PHC and to determine how these characteristics differ from those of general and OW populations in order to improve the targeting of PHC resources to individualize treatment and reduce dropout rates. The objective of this study was to explore the characteristics, lifestyle habits, and health conditions of individuals seeking a health promotion and weight reduction program in PHC.

Materials and methods

Design and settings

The study used a comparative cross-sectional design and was performed in a PHC setting in the southwestern part of Sweden. The study was performed at three PHC centers located in different cities and socioeconomic areas.

Study population

The participants were recruited (using adverts in local newspapers and direct recruitment at the three PHC centers) to a 2-year PHC weight reduction intervention study. The participants were randomized to a high- and low-intensive group. Both groups underwent laboratory tests and physical examinations, and filled in a questionnaire. They also received a cook book on the Nordic dietCitation15 and a dietary lecture. The high-intensive group also underwent motivational interviewing.Citation16 Both groups were followed up after 2 years. The inclusion criteria were being aged 40–65 years and having a BMI of 28–35 kg/m2. The exclusion criteria were undergoing treatment that could be affected by study participation (such as chemotherapy or radiation), having known drug problems, and not understanding or being able to use Swedish in speech or writing.

Reference populations

Two reference populations were selected: one OW reference population (ORP) (40–65 years of age, BMI 28–35 kg/m2) from the same region as the study population and one general population (GRP; 40–65 years of age, mean BMI 26 kg/m2). Data for both reference populations were obtained from the national population study known as “Health on Equal Terms” (HLV)Citation17 ().

Table 1 Population characteristics

Data collection

The study population’s baseline data for the 2-year weight reduction program were collected between March 2011 and April 2014. Data were collected through Web-based questionnaires. The physical measurements (BMI, etc) were obtained and blood samples (hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c], etc) were taken by a nurse at the three PHCs during the first visit and after 2 years. The definition for each education level was based on the standards in Statistics Sweden, BA034.Citation18 This classification consists of six education levels, with an algorithm defining three overall levels (low, medium, and high). The data collection for the two reference populations occurred between February and March 2014 using the HLV questionnaire.Citation17

Instruments

General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12)

Psychological well-being was assessed using the GHQ-12, which was developed as a screening instrument for mental illness.Citation19 The instrument, which has been validated and used worldwide, includes 12 questions and each uses an ordinal scale. The responses were dichotomized as good or impaired psychological well-being.Citation20

National health survey (HLV 2014)

The questions in the national health survey relate to physical and mental health, drug consumption, health care contacts, dental health, lifestyle, economic conditions, labor and employment, safety, security, and social relations. The questionnaire includes 80 issues. The survey has been administered nationally every year in Sweden since 2004, and at the regional level, it is performed every fourth year. In this study, we selected seven of the questionnaire domains: health status, health conditions, humiliation, symptoms, diseases, health care visits, and lifestyle.

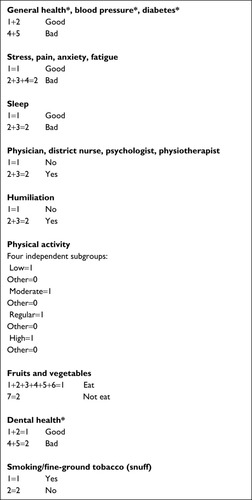

The question “How would you rate your general health condition?” had a 5-point ordinal response scale (ranging from very good to very bad), which was converted into a dichotomous item consisting of the options good and bad.Citation17 Dichotomization was also performed for the following domains (which contained items assessed using ordinal scales): health conditions, humiliation, pain symptoms, sickness, health care visits, and lifestyle. The other variables were items with dichotomous responses in their original forms ().

Figure 1 Dichotomization criteria used for the reference groups from a national health survey in Sweden (HLV 2014).

Statistics

The study population was compared with the two reference populations. Descriptive statistics were used to obtain the primary results. For comparison between populations, the chi-squared test was performed. The significance level was set at P=0.05.

Ethical approval

The Central Ethical Review Board of the University of Stockholm granted permission for this study (no 29–2010). Additionally, prior ethics approval was obtained for the 2015 intervention health care study Dietary Advice on Prescription “DAP” (no 2010/543). Participants were informed about the aim of the study, their right to withdraw at any time without consequences, and that the data would be stored and analyzed confidentially and only be available to the researchers. When the participants agreed to participate, they were asked to sign a consent form.

Results

There were 286 participants (231 women) in the weight reduction study, with an overall response rate of 93% (n=266). There were more women in the study population compared to the two reference populations (). The mean age was 55 years (SD 7.1), and the mean BMI was 31 (SD 2.0). Both values were higher than those of the reference populations (). Most participants in the study population had a low or medium level of education, but there were more participants with a low education level in the OW reference population (). There were no significant differences in education level between the three PHC centers.

Study population compared to the OW reference population (ORP)

There was no difference in self-reported well-being in the study population compared to the ORP, but a lower proportion in the study population reported good general health ( and ). In contrast, oral health was better in the study population than in the ORP.

Table 2 Health questionnaire responses among women

Table 3 Health questionnaire responses among men

Regarding health care consumption for women, the level was significantly higher among the study participants compared to the ORP for visits to district nurses, physiotherapists, and psychologists; however, they visited physicians less frequently. Regarding men, only the visits to physiotherapists were increased compared to the ORP.

The men in the study population (but not women) also reported more humiliation than the men in the ORP ( and ).

Regarding pain, the women in the study population had more hand pain than the ORP.

Regarding diabetes, neither women nor men showed an increased prevalence compared to the corresponding subgroups in the ORP ( and ).

In terms of lifestyle habits, tobacco use did not differ significantly between the study population and the ORP ( and ). There were no significant differences in physical activity for women; however, there were fewer men with low activity level in the study population than the ORP. There were no significant differences in the consumption of fruits and vegetables.

Study population compared to the general reference population (GRP)

The study population reported worse general health than the GRP; however, oral health was better in the study population.

Regarding health care consumption for women, there were significantly higher levels among the study participants than the GRP for visits to district nurses, physiotherapists, and psychologists; however, they visited physicians less frequently.

Both women and men in the study population reported more stress and humiliation than the corresponding subgroups in the GRP, and women reported more fatigue but less anxiety ( and ). Regarding pain, the women in the study population had more back pain than the women in the GRP, while the men had more shoulder pain than the men in the GRP.

Both women and men in the study population had higher blood pressure than the corresponding groups in the GRP, but there was no increased prevalence of diabetes compared to the prevalence in the GRP.

Discussion

The individuals seeking a weight reduction program were mostly women and they had a higher education level than the ORP. They also differed in terms of having worse general health than the ORP, despite not reporting worse psychological well-being, as measured by the GHQ12.Citation19 General health includes physical health, and many of the study participants had body pain, which could have affected how they rated their health. A previous survey that followed OW and obese individuals between 2002 and 2010 showed that the risk of pain and low general health increased with increasing BMI.Citation21 However, our findings differed from those of another study, which found both worse general health and impaired psychological well-being in obese women in Spain.Citation22

Oral health was better in the study population compared to both the ORP and GRP. There is a link between increased education and better oral health and also between increased education and less smoking, which also leads to better oral health.Citation23,Citation24

The study population, particularly women, utilized more health care services than the reference groups, except for general practitioner visits, and other studies also demonstrated that women tend to use health care more frequently than men and medical conditions (eg, hypertension, diabetes, and mental illness) were common.Citation25,Citation26 OW individuals are often prepared to try many different solutions to improve their general health,Citation27 which may be one of the reasons why they were frequent visitors to PHC facilities.

The study population felt more humiliated than the general population, in accordance with other studies.Citation28,Citation29 A previous study showed that, compared with diseases “believed to be caused by individuals themselves”, such as obesity and HIV/AIDS, persons with diseases experienced less sympathy both in health care settings and in wider society.Citation30 This is not a fact or the opinion of a health professional but the opinion or perception of some parts of the population. There are documented links between perceived weight stigmatization and adverse health consequences, such as binge eating, increased food consumption, avoidance of physical activity, physiological stress, and impaired weight loss outcomes.Citation31

Another finding that distinguished our study participants from the GRP was that they had more symptoms, such as shoulder, back, and hand pain, stress, and fatigue, than the GRP. It has been shown that there is a relationship between BMI, chronic pain, and reduced quality of life, and it seemed to be aligned with increasing BMI.Citation22 As mentioned, the study population also reported more stress than the GRP. Perceived stress is connected with a higher consumption of fat, snacks, and fast food but not necessarily a lower intake of fruits and vegetables,Citation32 as was the case in our study. The women in the study also felt more fatigue compared to the women in the GRP, despite the fact that there was no difference in sleeping disorders. There could be a stronger connection between stress, anxiety, and fatigue among women because they often take on more responsibilities in the home.Citation33 Diabetes has been shown to be common among OW individuals,Citation34 but in our study, the study participants did not show a higher prevalence than the other reference groups. The study participants’ blood pressure levels were higher compared to the GRP, which may be explained by higher BMI and increased stress.Citation35,Citation36

Negative lifestyle habits have been found to be independent determinants of frequent attendance at general practitioners’ offices; however, higher education and employment had a reduced attendance levels.Citation25,Citation26 The male study participants had a lower prevalence of low physical activity than the men in the ORP, which may be explained by their higher education levels, although a previous study suggests that self-reported physical activity questionnaires are less valid in populations with lower education levels.Citation37 Daily smoking has decreased in Sweden; however, smoking is still linked to low education levels,Citation38 which could explain the lower smoking prevalence in the study population compared to the ORP.

Methodological discussion

The GHQ-12 appears to be a good proxy for assessments of depressive disorder when used in public health surveys.Citation39 Self-rated health is a widely used measure of population health status. It correlates with physical health, functional capacity, and psychological well-being, and it is a significant predictor of morbidity, mortality, and health care utilization.Citation40

The strengths of this study include the possibility for comparisons, both at the national and regional levels. The use of validated instruments increases the validity of the questions. The study assessments did not occur at exactly the same time as the data collection for the two reference groups; however, they were matched to approximately the same time period (February and March 2014). Furthermore, the amalgamation of responses into dichotomized responses can reduce the nuance in the responses, and we used the same method as that used in the reference population research.Citation17

The study population consisted of more women than men (81% women), which is often the case in these types of intervention studies about weight loss .Citation41 The study population was self-selected, which may explain the higher education level and higher proportion of women compared to those in the ORP and GRP, which could have influenced the results. Women in their 50s, with low education and chronic illness, sought more PHC treatment,Citation42 though our study showed that women with high education sought more PHC treatment. However, these are the conditions in a PHC setting. The study participants were divided by gender to determine whether there were any major differences with corresponding subgroups in the ORP and GRP ( and ), and it was found that there were differences in the frequency of health care attendance and symptoms such as anxiety and fatigue. Our study participants had a mean age of 2 years older than the ORP and GRP participants, which is unlikely to have affected the outcomes. Three PHC centers were chosen to ensure socioeconomic diversity; however, the education level was higher in the study population than the ORP (but not the GRP). People with high school diplomas, regardless of their literacy levels and other sociodemographic factors, are more likely to seek and use health information. Education levels and literacy levels are both strongly linked to health outcomes.Citation43

Conclusion

The individuals seeking the weight reduction program were mostly women, they had a higher education level than the OW population, and they also had worse general health, despite not reporting worse psychological well-being. They also utilized more health care services, except for general practitioner visits.

The men in the study population differed from the women, with more self-reported humiliation compared to the OW population among men but not among women. The study participants did not have more stress, diseases, or body pain compared to the OW population; however, they differed from the general population in terms of more humiliation and more stress but better lifestyle habits regarding smoking. OW is a complex condition, and these findings could be important to create improved professional PHC teams and adapt health care resources to each individual.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof Gunnar Johansson, who initiated the weight reduction program. We thank Capio Sjukvård AB for the support and Sparbanksstiftelsen Varberg for the production of this publication which does not constitute an endorsement of the study contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, therefore Capio Sjukvård AB and Sparbanksstiftelsen Varberg cannot be held responsible for any use of the information contained therein.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health Organizationhomepage on the InternetGenevaObesity and overweight2014 Available from: www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/Accessed Jan 22, 2017

- Public Health Agency of Sweden 2016homepage on the InternetSweden Available from: www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/2017Accessed March, 2017

- National Task Force on the prevention and treatment of obesityOverweight, obesity and health riskArch Intern Med2000160789890410761953

- CoaccioliSMasiaFCeliGGrandoneICrapaMEFatatiGDolore Cronico nell’obecità: studio ossevazionale quali-quantitativo [Chronic pain in the obese: a quali-quantitative observational study]Recenti Prog Med20141054151154 Italian24770540

- PaansNPBotMGibson-SmithDThe association between personality traits, cognitive reactivity and body mass index is dependent on depressive and/or anxiety statusJ Psychosom Res201689263127663107

- FukudaKStrausSEHickieISharpeMCDobbinsJGKomaroffAThe chronic fatigue syndromeAnn Intern Med1994121129539597978722

- KorhonenPESeppäläTJärvenpääSKautiainenHBody mass index and health-related quality of life in apparently healthy individualsQual Life Res2014231677423686578

- MetzUWelkeJEschTRennebergBBraunVHeintzeCPerception of stress and quality of life in overweight and obese people-implications for preventive consultancies in primary careMed Sci Monit2009151PH1PH619114978

- van SteenkisteBKnevelMFvan den AkkerMMetsemakersJFMIncreased attendance rate: BMI matters, lifestyles don’t. Results from the Dutch SMILE studyFam Pract201027663263720696755

- GiskesKAvendaňoMBrugJKunstAEA systematic review of studies on socioeconomic inequalities in dietary intakes associated with weight gain and overweight/obesity conducted among European adultsObes Rev201011641342919889178

- DeckKMHaneyBFitzpatrickCFPhillipsSJTisoSMPrescription for obesity: eat less and move more. Is it really that simple?Open J Nurs201449656662

- SikorskiCLuppaMKaiserMThe stigma of obesity in the general public and its implications for public health – a systematic reviewBMC Public Health201111166121859493

- Dalle GraveRCalugiSMolinariEQUOVADIS Study GroupWeight loss expectations in obese patients and treatment attrition: an observational multicenter studyObes Res200513111961196916339128

- De PanfilisCTorreMCeroSPersonality and attrition from behavioral weight-loss treatment for obesityGen Hosp Psychiatry200830651552019061677

- AdamssonVReumarkAFredrikssonIBEffects of a healthy Nordic diet on cardiovascular risk factors in hypercholesterolaemic subjects: a randomized controlled trial (NORDIET)J Intern Med2011269215015920964740

- GraneheimUHLundmanBQualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthinessNurse Educ Today200424210511214769454

- National Health Survey 2014homepage on the InternetSweden Available from: www.fhi.seAccessed January, 2017

- Utbildningsnivån SUN 2000 NIVAThe Education codes and levels (SUN 2000)Statistiska Centralbyrån (SCB), Statistics Sweden 2018; ÖrebroSweden Available from: https://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Publiceringskalender/Visa-detaljerad-information/?publobjid=2061Accessed April, 2018

- GoldbergDPWilliamsPAUser’s guide to the general health questionnaire. Windsor: NFER/NelsonSoc Psych Psychiatric Epidem198811213218

- LundinAÅhsJÅsbringNDiscriminant validity of the 12-Item version of the general health questionnaire in a Swedish case-control studyNord J Psychiatry201771317117927796153

- HolmgrenMLindgrenAde MunterJRasmussenFAhlströmGImpacts of mobility disability and high and increasing body mass index on health-related quality of life and participation in society: a population-based cohort study from SwedenBMC Public Health201414138124742257

- Martín-LópezRPérez-FarinósNHernández-BarreraVde AndresALCarrasco-GarridoPJiménez-GarcíaRThe association between excess weight and self-rated health and psychological distress in women in SpainPublic Health Nutr20111471259126521477413

- PaulanderJAxelssonPLindheJAssociation between level of education and oral health status in 35-, 50-, 65- and 75-year-oldsJ Clin Periodontol200330869770412887338

- AxelssonPPaulanderJLindheJRelationship between smoking and dental status in 35-, 50-, 65-, and 75-year-old individualsJ Clin Periodontol19982542973059565280

- ChenRTunstall-PedoeHSocioeconomic deprivation and waist circumference in men and women: The Scottish MONICA surveys 1989–1995Eur J Epidemiol200520214114715792280

- KoskelaTHRyynanenOPSoiniEJRisk factors for persistent frequent use of the primary health care services among frequent attenders: a Bayesian approachScand J Prim Health Care2010281556120331389

- ElfhagKRössnerSWho succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regainObes Rev200561678515655039

- KushnerRFThe burden of obesity: personal stories, professional insightsNarrat Inq Bioeth20144212913325130352

- ThomasSLHydeJKarunaratneAHerbertDKomesaroffPABeing ‘fat’ in today’s world: a qualitative study of the lived experiences of people with obesity in AustraliaHealth Expect200811432133018684133

- PuhlRMHeuerCAObesity stigma: important considerations for public healthAm J Public Health201010061019102820075322

- PuhlRSuhYHealth consequences of weight stigma: implications for obesity prevention and treatmentCurr Obes Rep20154218219026627213

- BarringtonWEBeresfordSAMcGregorBAWhiteEPerceived stress and eating behaviors by sex, obesity status, and stress vulnerability: findings from the vitamins and lifestyle (VITAL) studyJ Acad Nutr Diet2014114111791179924828150

- JaroszPADavisJEYarandiHNObesity in urban women: associations with sleep and sleepiness, fatigue and activityWomens Health Issues2014244e447e45424981402

- American Diabetes AssociationStandards of medical care in diabetes-2013Diabetes Care201336Suppl 1S11S6623264422

- HigginsMKannelWGarrisonRPinskyJStokes J 3rd. Hazards of obesity-the Framingham experienceActa Med Scand Suppl198872323363164971

- CarrollDRingCHuntKFordGMacintyreSBlood pressure reactions to stress and the prediction of future blood pressure: effects of sex, age, and socioeconomic positionPsychosom Med20036561058106414645786

- WinckersANEMackenbachJDCompernolleSEducational differences in the validity of self-reported physical activityBMC Public Health2015151129926856811

- Public Health Agency of Sweden 2017homepage on the InternetSweden Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/livs-villkor-levnadsvanor/alkohol-narkotika-dopning-tobak-och-spel-andts/tobak/utvecklingen-av-bruket/bruk-av-cigaretter-snus-och-e-cigaretter-i-den-vuxna-befolkningen/Accessed March, 2017

- LundinAHallgrenMTheobaldHHellgrenCTorgénMValidity of the 12-Item version of the general health questionnaire in detecting depression in the general populationPublic Health2016136667427040911

- CandemirIErgunPKaymazDEfficacy of a multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation outpatient program on exacerbations in overweight and obese patients with asthmaWien Klin Wochenschr201712919–2065566428894957

- MelchartDLöwPWührEKehlVWeidenhammerWEffects of a tailored lifestyle self-management intervention (TALENT) study on weight reduction: a randomized controlled trialDiabetes Metab Syndr Obes2017101023524528684917

- GomesJMachadoACavadasLFThe primary care frequent attender profileActa Med Port20132611723 Portuguese23697353

- EgerterSBravemanPSadegh-NobariTGrossman-KahnRDekkerMIssue Brief 6: Education and HealthPrinceton, NJRobert Wood Johnson Foundation2009