Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive and debilitating but preventable and treatable disease characterized by cough, phlegm, dyspnea, and fixed or incompletely reversible airway obstruction. Most patients with COPD rely on primary care practices for COPD management. Unfortunately, only about 55% of US outpatients with COPD receive all guideline-recommended care. Proactive and consistent primary care for COPD, as for many other chronic diseases, can reduce hospitalizations. Optimal chronic disease management requires focusing on maintenance rather than merely acute rescue. The Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH), which implements the chronic care model, is a promising framework for primary care transformation. This review presents core PCMH concepts and proposes multidisciplinary team-based PCMH care strategies for COPD.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive and debilitating but preventable and treatable disease characterized by cough, phlegm, dyspnea, and fixed or incompletely reversible airway obstruction.Citation1 Only 55% of US outpatients with COPD and 33% of COPD inpatients receive all guideline-recommended care.Citation2 Gaps in care for COPD and other chronic diseases do not merely result from underfunding. Regions of the US costing Medicare the most do not necessarily do better on care quality indicators than less costly, but otherwise similar, regions.Citation3,Citation4 Focus on reimbursable procedures rather than evidence-based primary care is often the culprit.Citation3 Primary management of chronic diseases requires more integrative “thinking” than technological “doing”,Citation5 and is too often underpaid and undervalued relative to its importance to patients.Citation3

Superficial remedies, ie, “just trying harder” and primary care gatekeeping, will not improve patient outcomesCitation6 or cure cost disparities.Citation7 Redesign of practice is needed to facilitate proactive primary care of chronic conditions and integrated and accountable delivery of specialty and inpatient services.Citation8 The Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) is a promising framework for this practice transformation. Multiple professions, including physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners, as well as nurses, medical assistants, and registered respiratory therapists, all have roles to play in team-based PCMH care for COPD.

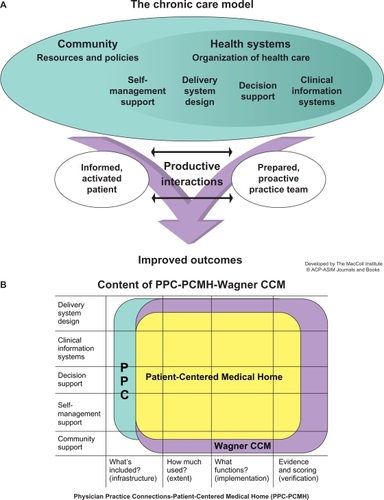

The PCMH implements, refines, and extends the principles of its predecessor, the chronic care model ().Citation9 Multidisciplinary team care focused on maintaining wellness, rather than merely reacting to acute illness, is central to the chronic care model and the PCMH.Citation10,Citation11 Because providing all current guideline-recommended care to patients in an average practice would require nearly three full-time primary care providers, practices need to reorient to a team approach in which physician assistants and/or nurse practitioners do most first-contact care, and physicians lead the care team and manage complex patients.Citation12 PCMH demonstration projects have found expansion of multidisciplinary allied-health roles indispensable for a sustainable PCMH transition.Citation13 This shift from physician-centered to a team approach may be the greatest personal challenge a physician faces in the PCMH transition.Citation14

Figure 1 The chronic care model (CCM).

Accountable care organizations can be considered integrated “medical villages” for the PCMH, coordinating evidence-based and cost-effective specialty and inpatient services with primary care.Citation8,Citation15 Proactiveness, quality, and continuity of primary care for COPD, as for other “ambulatory care-sensitive” chronic diseases, are crucial in reducing inpatient utilization.Citation16 Thus, COPD care stands to benefit from the PCMH-accountable care organization approach. This review will present core PCMH concepts and discuss multidisciplinary team-based PCMH care strategies for COPD.

PCMH components, certification, and compensation

The American Academy of Family Practice model of the PCMH is shown in . PCMH principles were jointly developed by the American Academy of Family Practice, American College of Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American Osteopathic Association,Citation10 and their contents are summarized with COPD examples in . Elements scored in the 2011 standards and guidelines for Physician Practice Connections (PPC)-PCMH recognition evaluations are shown in .Citation17 Although PPC-PCMH, like the joint principles, defines a PCMH as physician-led, the PCMH resource organization, TransforMEDSM, also recognizes PCMH practices led by physician assistants or nurse practitioners.

Figure 2 The American Academy of Family Practice model of the Patient-Centered Medical Home.

Table 1 TransforMED PCMH Principles (http://www.transformed.com/pdf/TransforMEDMedicalHomeModel-letter.pdf) and their potential applications to COPD

Table 2 Practice components evaluated for PPC-PCMH recognitionCitation17

PCMH care is labor-intensive behind the scenes as well as in patient visits and should be compensated accordingly. Fee-for-service excludes nonvisit work and encourages overuse. Salary alone does not reward productivity, pure capitation encourages underuse, and pay for performance may shortchange unmetricated care. The American College of PhysiciansCitation18 therefore advocates blended payment that retains visit-based fee-for-service payments and adds prospective, bundled payments for the structural overhead of PCMH practices and for care-coordinating “desktop medicine” activities.Citation13 The final component is pay for performance, thus rewarding quality and efficiency goals.

Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound conducted a 12-month quasi-experimental study comparing a designated PCMH practice with usual care clinics.Citation13 Prior to the study, electronic health records and same-day scheduling had been adopted systemwide. The PCMH demonstration clinic reduced clinicians’ case loads from about 2300 to 1800 patients, increased standard visits from 20 to 30 minutes, provided protected “desktop medicine” time, and altered the staff mix, raising physician assistant staffing levels by 44%, registered nurses by 17%, medical assistants and licensed practical nurses by 18%, and clinical pharmacists by 72%.Citation13 At the end of 12 months, PCMH patients had 29% fewer emergency room/urgent care visits and 11% fewer hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (including COPD) than usual care patients. Overall costs were unchanged between the PCMH and usual care, staff burnout levels were significantly reduced, and quality indicators improved significantly more in the PCMH than in usual care.Citation13 The Group Health experience exemplifies the importance of multidisciplinary contributions to PCMH success.

Contributions of physician assistants and nurse practitioners

Physician assistants and nurse practitioners play important roles in PCMH transformation of practices and development of team care workflows for COPD management. They can help change care culture from reactive to proactive, combat therapeutic pessimism, and design and implement COPD care processes. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners at the first-line primary care interface can combat patients’ denial of COPD, encourage smoking cessation, institute maintenance treatment, and enable self-management. PCMH team members collaborating with patients can develop concordant care plans, making it easier for the patient to persevere with a smoke-free, active lifestyle and to remain on appropriate medication.

Chronic care for COPD should strive to reduce the risk of exacerbations and delay their onset to reduce health care burden and improve health-related quality of life. The elements of primary care COPD management include smoking cessation, immunizations, physical activity, pulmonary rehabilitation (if dyspnea and functional disability are present), acute care of exacerbations arising, and maintenance pharmacotherapy to reduce exacerbations.Citation1

Smoking cessation, especially before the age of 40–45 years, slows loss of lung function in COPD to a rate usual for age.Citation19 Evidence-based smoking cessation assistance should be offered to patients choosing to quit.Citation1,Citation20

Major COPD guidelines recommend that maintenance treatment with long-acting inhaled anticholinergic or β-adrenergic agents begin no later than moderate COPD.Citation1 Maintenance treatment of COPD may reduce severity of symptoms, reduce exacerbations, maintain activity, and improve health-related quality of life. Tiotropium is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for maintenance treatment of bronchospasm associated with COPD and to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients; salmeterol/fluticasone is also approved by the FDA for maintenance treatment of airway obstruction in COPD and to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients with a history of exacerbations. Budesonide/formoterol is approved by the FDA for maintenance treatment of airway obstruction in COPD but does not have an approved indication to reduce exacerbations. Oral roflumilast received FDA approval on March 1, 2011 to reduce the risk of exacerbations of COPD in patients with severe COPD associated with chronic bronchitis and a history of exacerbations (http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm244989.htm; http://www.frx.com/news/PressRelease.aspx?ID=1534051). The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines of 2010 state that roflumilast may be combined with long-acting bronchodilators.Citation1 Maintenance therapies that have been shown to improve exercise parameters in patients with COPD include tiotropium,Citation21 salmeterol/fluticasone,Citation22 combined tiotropium and salmeterol/fluticasone,Citation23 combined tiotropium and formoterol,Citation24 budesonide/formoterol,Citation25 salmeterol alone,Citation26 or formoterol alone.Citation27 Improving patients’ capacity for physical activity may enhance both pulmonary rehabilitation and valued life activities. Care team members can connect COPD patients with pulmonary rehabilitation and encourage routine physical activity, forestalling progressive deconditioning and worsening dyspnea.Citation28

PCMH team members, including physician assistants, nurse practitioners, registered respiratory therapists, and/or designated and specially trained health coachesCitation29 (who may be nurses, medical assistants, or health educators), can teach and empower patients to self-manage COPD between office visits. Exacerbation self-management action plans (such as the Canadian Thoracic Society plan available online at http://www.lung.ca/pdf/1408_THOR_ActionPlan_v3.pdf) can help patients recognize and medicate exacerbations promptly and discern when to visit the primary care clinic or emergency room. Self-management support reduces health care utilization in COPD. Provision of one education session, an exacerbation action plan, and a monthly telephone follow-up to US veterans with severe COPD reduced COPD-related hospitalizations/emergency room visits by 41%.Citation30

PCMH-based solutions to challenges in COPD management

PCMH methods provide multiple ways to improve COPD care (), where “practice as usual” has encountered challenges. Continuous healing relationships for whole-person care can change episodic, reactive, and emergent COPD care into planned ongoing proactive management. In current practice, COPD care is often driven by exacerbation emergencies,Citation31 with acute non-respiratory problems and multiple comorbidities taking primary care physician visit time away from COPD concerns.Citation11 Scheduled well-care visits (eg, every four months) devoted to COPD maintenance are a potential PCMH solution.Citation32 Some practices that conduct well-care COPD visits find that patients spontaneously evolve into an informal peer support group.

Access to care and information can reduce COPD-related emergency room use and help patients and families cope. Prompt primary care of exacerbations improves outcomes, yet is difficult to achieve in current practice. Direct emergency room visits for exacerbations are sometimes the initial presentation of undiagnosed and unaware COPD patients.Citation31,Citation33 Emergency room visits may result from after-hours acute events but also from patients’ difficulty in scheduling prompt primary care physician visits. Advanced access to same-day primary care in COPD chronic care programs reduces inpatient and emergency room utilization.Citation34 Group visits, which is another PCMH emphasis, allow interactive and efficient COPD maintenance and patient education. Nurse practitioners or physician assistants can effectively conduct group visits,Citation35 and registered respiratory therapists can teach inhaler technique for any stage of COPD and proper long-term oxygen use for hypoxemic severe COPD. Diabetes care has a well developed group visit methodology;Citation36 but COPD group visit models need further research.

Practice-based services and care management in the PCMH can integrate COPD diagnosis and treatment resources. In current practice, COPD diagnosis is often recorded without performing spirometry,Citation37 maintenance treatment is underused, and adherence and persistence are insufficiently monitored.Citation38 More newly diagnosed COPD patients received primary care physician practice-based spirometry in the Group Health Cooperative PCMH demonstration clinic than in usual care clinics.Citation13 Practice-based spirometry also may help reduce tobacco use and COPD progression; smokers who learn that they have spirometric airway obstruction are more likely to quit.Citation39 Chronic disease patient registries help a practice to improve the health of its COPD patient population.Citation40 Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set indicators applicable to COPD care may be appropriate for within-practice tracking as well as public reporting. Additional registry contents may include exacerbation rates, primary care physician follow-up after exacerbations, prescription refill rates, activity levels, employment/retirement status, and household members.

Care coordination and electronic communication can improve care transitions. If primary care providers remain unaware when their own patients are hospitalized for exacerbations, maintenance treatment may not be restarted at discharge,Citation41 heightening the risk of recurrent exacerbations.Citation42,Citation43 In addition, lung function test results or pulmonologists’ reports may not promptly reach all primary care team members. A recent evaluation showed that Group Health Cooperative PCMH patients were 1.89 times more likely than usual care patients to receive a call or secure email from a primary care physician within three days of hospital or emergency room discharge.Citation13

Practice-based care teams can consciously assign COPD management tasks (smoking cessation support, inhaler technique instruction, and adherence monitoring) to specific members of the care team so that nothing needful is omitted. In a successful PCMH workflow, the division of tasks depends on individual skill sets rather than on rigid job descriptions, and every team member works at his or her highest licensed level of care.

Quality and safety systems, including meaningful electronic health records use and evidence-based decision support, are central to the PCMH. In current practice, guidelines are often not followed,Citation2 and patients on maintenance treatment may be insufficiently followed up regarding adherence.Citation38 Guideline-based COPD careCitation1 includes diagnostic postbronchodilator spirometry, short-acting bronchodilators, maintenance treatment, and pulmonary rehabilitation beginning at moderate COPD, and influenza and pneumonia vaccinations. Electronic reminders help clinicians implement guidelines, and electronic prescribing can track patient medication use, adherence, and potential drug interactions. An electronic COPD registry can track exacerbation rates to reduce them over time. Electronic health records, electronic prescribing, and guideline reminders are required for tiers 2 and 3 of PPC-PCMH certification. Publicly reportable Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set indicators relevant to COPD are shown in .

Table 3 Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information set 2011 indicators relevant to COPD care

Practice management patterns in the PCMH emphasize planned, coordinated, and reflective chronic care, in contrast with current practice focusing on acute care episodes and payment for procedures.Citation8 In a fee-for-service system, lack of payment for care coordination and registry-related tasks is a disincentive to expend energy on them.Citation18 PCMH payment structures should reflect the value of PCMH care planning and management (). The accountable care organization approach includes specialty, inpatient, and emergency room services in an integrated and electronically interoperable patient-centered medical village, sharing in the Medicare savings it generates by coordinating care rather than driving supply-sensitive utilization.Citation8,Citation15,Citation44 Optimizing payment models for PCMH care patterns provides an economically viable and sustainable practice.

Conclusion

The PCMH model has the potential to improve outcomes in chronic diseases, such as COPD, by shifting the primary care focus from acute rescue to proactive maintenance and by shifting practice culture from maximizing reimbursable specialty procedures to maintaining coordinated, reflective, and accountable chronic disease care. PCMH-based multidisciplinary redesign of the COPD care workflow offers new approaches to primary care and patient education that will contribute critically to improving patient outcomes and controlling costs in a sustainable health care system.

Acknowledgements

This article was developed on the basis of presentations and discussions by the authors at the Overcoming Barriers to COPD Identification and Management task force meeting in New York, NY, March 22–23, 2009. This meeting, author participation, and manuscript preparation were supported by funding from Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc. Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Kim Coleman Healy, of Envision Scientific Solutions, which was contracted by BIPI for these services. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, and were involved at all stages of review article development. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the review article. The article reflects the concepts of the authors and is their sole responsibility. It was not reviewed by BIPI and Pfizer Inc, except to ensure medical and safety accuracy.

Disclosure

GO has been a consultant to Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc, CSL Behring, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough/Merck, Sepracor, and TEVA, and currently serves as a consultant for Dey, Merck, Sunovion, and TEVA, and is a speakers’ bureau member for Phadia AS, Merck, and TEVA. LF has received speakers’ bureau honoraria from Boehringer-Ingelheim Inc and Pfizer and is a member of the board of TransforMED, LLC; a not for profit subsidiary of the American Academy of Family Practice.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD122010 http://www.goldcopd.com/Guidelineitem.asp?l1=2&l2=1&intId=989. Accessed March 14, 2011.

- MularskiRAAschSMShrankWHThe quality of obstructive lung disease care for adults in the United States as measured by adherence to recommended processesChest200613061844185017167007

- GawandeAThe cost conundrumNew Yorker612009

- FisherESWennbergDEStukelTAGottliebDJLucasFLPinderELThe implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2: health outcomes and satisfaction with careAnn Intern Med2003138428829812585826

- Blue Ribbon Panel of the Society of General Internal MedicineRedesigning the practice model for general internal medicine. A proposal for coordinated care: a policy monograph of the Society of General Internal MedicineJ Gen Intern Med200722340040917356976

- Institute of MedicineCrossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st centuryWashington, DCNational Academy Press2001

- MirabitoAMBerryLLLessons that patient-centered medical homes can learn from the mistakes of HMOsAnn Intern Med2010152318218520124235

- RittenhouseDRShortellSMFisherESPrimary care and accountable care – two essential elements of delivery-system reformN Engl J Med2009361242301230319864649

- WagnerEHChronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness?Eff Clin Pract1998112410345255

- American Academy of Family PhysiciansJoint principles of the Patient-Centered Medical HomeDel Med J2008801212218284087

- BodenheimerTWagnerEHGrumbachKImproving primary care for patients with chronic illnessJAMA2002288141775177912365965

- YarnallKSOstbyeTKrauseKMPollakKIGradisonMMichenerJLFamily physicians as team leaders: “time” to share the carePrev Chronic Dis200962A5919289002

- ReidRJFishmanPAYuOPatient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluationAm J Manag Care2009159e71e8719728768

- NuttingPAMillerWLCrabtreeBFJaenCRStewartEEStangeKCInitial lessons from the first national demonstration project on practice transformation to a patient-centered medical homeAnn Fam Med20097325426019433844

- FisherESMcClellanMBBertkoJFostering accountable health care: moving forward in MedicareHealth Aff (Millwood)2009282w219w23119174383

- BindmanABChattopadhyayAAuerbackGMInterruptions in Medicaid coverage and risk for hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditionsAnn Intern Med20081491285486019075204

- National Committee for Quality AssurancePCMH 2011 StandardsWashington, DCNational Committee for Quality Assurance2011

- American College of PhysiciansA System in Need of Change: Restructuring Payment Policies to Support Patient-Centered Care. [PositionPaper]Philadelphia, PAAmerican College of Physicians2006

- YoungRPHopkinsREatonTEForced expiratory volume in one second: not just a lung function test but a marker of premature death from all causesEur Respir J200730461662217906084

- RadinACoteCPrimary care of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – part 1: frontline prevention and early diagnosisAm J Med20081217 SupplS3S1218558105

- MaltaisFHamiltonAMarciniukDImprovements in symptom-limited exercise performance over 8 h with once-daily tiotropium in patients with COPDChest200512831168117816162703

- O’DonnellDESciurbaFCelliBEffect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol on lung hyperinflation and exercise endurance in COPDChest2006130364765616963658

- PasquaFBiscioneGCrignaGAucielloLCazzolaMCombining triple therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with advanced COPD: a pilot studyRespir Med2010104341241719892540

- BertonDCReisMSiqueiraACEffects of tiotropium and formoterol on dynamic hyperinflation and exercise endurance in COPDRespir Med201010491288129620580216

- WorthHForsterKErikssonGNihlenUPetersonSMagnussenHBudesonide added to formoterol contributes to improved exercise tolerance in patients with COPDRespir Med2010104101450145920692140

- O’DonnellDEVoducNFitzpatrickMWebbKAEffect of salmeterol on the ventilatory response to exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J2004241869415293609

- NederJAFuldJPOverendTEffects of formoterol on exercise tolerance in severely disabled patients with COPDRespir Med2007101102056206417658249

- PittaFTroostersTProbstVSLangerDDecramerMGosselinkRAre patients with COPD more active after pulmonary rehabilitation?Chest2008134227328018403667

- BodenheimerTLaingBYThe teamlet model of primary careAnn Fam Med20075545746117893389

- RiceKLDewanNBloomfieldHEDisease management program for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182789089620075385

- ZoiaMCCorsicoAGBeccariaMExacerbations as a starting point of pro-active chronic obstructive pulmonary disease managementRespir Med200599121568157515890509

- BodenheimerTPlanned visits to help patients self-manage chronic conditionsAm Fam Physician20057281454145616273815

- BastinAJStarlingLAhmedRHigh prevalence of undiagnosed and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at first hospital admission with acute exacerbationChron Respir Dis201072919720299538

- AdamsSGSmithPKAllanPFAnzuetoAPughJACornellJESystematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and managementArch Intern Med2007167655156117389286

- WattsSAGeeJO’DayMENurse practitioner-led multidisciplinary teams to improve chronic illness care: the unique strengths of nurse practitioners applied to shared medical appointments/group visitsJ Am Acad Nurse Pract200921316717219302693

- KirshSWattsSPascuzziKShared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular riskQual Saf Health Care200716534935317913775

- WalkerPPMitchellPDiamanteaFWarburtonCJDaviesLEffect of primary-care spirometry on the diagnosis and management of COPDEur Respir J200628594595216870668

- RestrepoRDAlvarezMTWittnebelLDMedication adherence issues in patients treated for COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083337138418990964

- ParkesGGreenhalghTGriffinMDentREffect on smoking quit rate of telling patients their lung age: the Step 2 quit randomised controlled trialBMJ2008336764459860018326503

- JonesRCDickson-SpillmannMMatherMJMarksDShackellBSAccuracy of diagnostic registers and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Devon primary care auditRespir Res200896218710575

- DrescherGSCarnathanBJImusSColiceGLIncorporating tiotropium into a respiratory therapist-directed bronchodilator protocol for managing in-patients with COPD exacerbations decreases bronchodilator costsRespir Care200853121678168419025702

- HurstJRDonaldsonGCQuintJKGoldringJJBaghai-RavaryRWedzichaJATemporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179536937419074596

- McGhanRRadcliffTFishRSutherlandERWelshCMakeBPredictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPDChest200713261748175517890477

- FisherESWennbergJEHealth care quality, geographic variations, and the challenge of supply-sensitive carePerspect Biol Med2003461697912582271

- American Academy of Family PracticePatient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Available from: http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/membership/initiatives/pcmh.html. Accessed September 29, 2011.

- National Committee for Quality AssuranceHEDIS 2011 Summary Table of Measures, Product Lines and Changes Available from: http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/HEDISQM/HEDIS%202011/HEDIS%202011%20Measures.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2011.