Abstract

Background

A number of studies indicated that prescribing errors in the intensive care unit (ICU) are frequent and lead to patient morbidity and mortality, increased length of stay, and substantial extra costs. In Ethiopia, the prevalence of medication prescribing errors in the ICU has not previously been studied.

Objective

To assess medication prescribing errors in the ICU of Jimma University Specialized Hospital (JUSH), Southwest Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the ICU of Jimma University Specialized Hospital from February 7 to April 15, 2011. All medication-prescribing interventions by physicians during the study period were included in the study. Data regarding prescribing interventions were collected from patient cards and medication charts. Prescribing errors were determined by comparing prescribed drugs with standard treatment guidelines, textbooks, handbooks, and software. Descriptive statistics were generated to meet the study objective.

Results

The prevalence of medication prescribing errors in the ICU of Jimma University Specialized Hospital was 209/398 (52.5%). Common prescribing errors were using the wrong combinations of drugs (25.7%), wrong frequency (15.5%), and wrong dose (15.1%). Errors associated with antibiotics represented a major part of the medication prescribing errors (32.5%).

Conclusion

Medication errors at the prescribing phase were highly prevalent in the ICU of Jimma University Specialized Hospital. Health care providers need to establish a system which can support the prescribing physicians to ensure appropriate medication prescribing practices.

Introduction

Medication errors (MEs) are major issues in health care and are probably one of the most common types of medical errors.Citation1,Citation2 These events may occur due to professional practice, health care products, and procedures such as prescribing, dispensing, and administration.Citation2 High error rates with serious consequences are most likely to occur in intensive care units but errors are minimized in the presence of intensivists.Citation1,Citation3 MEs are more common in ICUs, probably because of polypharmacy and a more stressful environment than other wards in the hospital.Citation1,Citation4–Citation7 The majority of errors are not due to reckless behavior on the part of health care providers, but occur as a result of the speed and complexity of the medication use cycle, combined with faulty systems, processes, and conditions that lead people to make mistakes or fail to prevent them.Citation1,Citation4–Citation6,Citation8

Prescribing errors in critical care units are frequent, serious, and expected, since these patients are prescribed twice as many medications as patients outside critical care.Citation1,Citation6–Citation7 More patients suffer a potentially life-threatening error at some point during their stay than patients in other hospital wards due to their decreased physiological reserves which increases the risks of harm from medication-related errors.Citation7,Citation9 Camire et al reported the point prevalence of medication errors in the ICU to be 10.5 per 100 patient-days, with the prescribing error rate being 54%.Citation7 However, there is wide variation in the definition of errors and the methods used to detect them.Citation6–Citation7,Citation10 Factors contributing to the frequency of MEs include: unobtainable medical history since most patients in the ICU are sedated (unable to identify potential errors by themselves); multiple medications being received; most medications in the ICU being given intravenously, where calculation of infusion rates is often required; and insufficient staff numbers.Citation1,Citation10,Citation11

The major consequences of MEs are patient morbidity and mortality.Citation4–Citation6 MEs can affect patients, families, and health care providers indirectly because of cost implications, prolonged hospital stays, and psychological impact, since errors erode public confidence in the health care service.Citation1,Citation6 However, data regarding MEs in Africa,Citation12 especially in Ethiopia is scarce. Information regarding MEs in the ICUs of Ethiopian health institutions is absent.

Owing to the staffing structure in the ICU, the settings in which patients are managed, and the types of medications commonly used in the Ethiopian context, we expected the type and prevalence of MEs to be different from those reported in other studies. Prescribing error was specifically chosen for this evaluation because of the absence of any system to support prescribing physicians, who usually rely on their memory, to ensure correct prescribing practice. Therefore, this study was initiated to determine the prevalence and types of medication errors in the prescribing phase in the ICU of JUSH, Southwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study area

A cross-sectional study was conducted from February 7 to April 15, 2011 in the ICU of JUSH, a teaching hospital located in Jimma, in Southwestern Ethiopia, 350 km southwest of the capital Addis Ababa. JUSH is the only referral hospital in the southwestern part of Ethiopia, with 450 beds and 558 health professionals, where a multidisciplinary team of diverse professionals provide a range of health care services for approximately 9000 inpatients and 80,000 outpatients each year. The ICU has six beds and serves critically ill patients from different departments of the hospital. Medication distribution is centralized and there is no floor-based decentralized pharmacy service currently available in the ICU.Citation12

Study subjects

All medication-prescribing interventions by all prescribing physicians for all patients admitted to the ICU during the data collection period were included in this study. Data regarding prescribing of medications were collected from patient cards and medication charts using a pre-tested data collection format.

Data collection process

Data were collected, using a structured format, by two clinical pharmacy postgraduate students who were instructed on how to approach the patients and health care professionals to obtain data from patient cards and medication charts. The content included demographic variables, dates and times of prescription, name of the medication, dosage forms, doses, frequency, and duration of medications prescribed. Demographic information about patients was obtained from patient cards and medication charts. Diagnostic test results were used to determine the accuracy of diagnosis, and thus determine appropriate medications for each patient. Health professionals who prescribed the drugs were given unique identification numbers until the end of the data collection period to prevent bias.

Prescribing errors were determined by comparing prescribed drugs with national standard treatment guidelines, textbooks, handbooks, and software.Citation13–Citation24 Data were edited, coded, and entered into SPSS (Windows v 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics were computed to determine specific errors and the overall prevalence of prescribing error.

Operational definitions

Prescribing error: implies deviation of medication prescribing from standard practices (as indicated in national standard treatment guidelines, textbooks, handbooks, and software) excluding dosage form errors, illegible hand writing, and failure to authenticate the prescription with signature and/or date.

Complex regimen: prescription of more than three drugs to one patient at the same time.

Antibiotics: in this study, implies antibacterial drugs.

Wrong combination: implies drug interactions and therapeutic duplications.

Omission error: implies medications ordered without specifying dose/frequency/route.

Wrong frequency: implies drugs prescribed with a frequency greater or less than what is recommended.

Wrong dose: implies the dose ordered by physician was higher or lower than what is recommended.

Wrong route: implies that the medication was prescribed to be given in a route other than the one recommended.

Wrong indication: implies the presence of incorrect indication and contraindications which were not noted by the prescribing physician.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of Jimma University. Before the start of data collection, permission was obtained from the hospital management and written consent was obtained from respondents. Moreover, the names of patients and health professionals were replaced with codes to avoid individual identifiers.

Results

Characteristics of interventions and participants

This study included 398 physician drug prescriptions for 69 patients who were admitted to the ICU of JUSH during the study period. Those medication orders with illegible handwriting (8.8%), failure to authenticate the medications with signature and date (30.9%), and dosage form errors were not included in the definition of prescribing errors.

The majority of the 69 patients (55.1%) were females, with 44 (63.8%) of them aged 18–50 years, and a mean age of 32.9 (±17.0) years. Fifty-four (78.3%) of them were admitted to other wards before they were admitted to the ICU. Thirty-two (46.4%) of the patients were unconscious and 49 (71.0%) received a complex regimen, with the average number of medications per patient being 5 (±2.0) drugs. Patients stayed an average of 5.654 (±5.2) days in the ICU, until death or transfer to other wards. The average number of comorbid conditions per patient was 3 ± 2.0 ().

Table 1 Characteristics of patients admitted to the ICU of JUSH, April 2011 (n = 69)

Twenty-seven physicians were involved in prescribing medications in the ICU during the data collection period. Almost all of the prescribers were in the age range 20–25 years and were males. Medical interns were most frequently involved in prescribing medications although they only had a 1-week-long stay in the ICU as part of their work experience in the internal medicine department (). About 13 (61.9%) of the physicians were off duty 1–4 nights per week but all of them took the day off following a night shift. The remaining eight (38.1%) of the physicians had part-time work outside the hospital during the data collection period. Eleven (52.4%) physicians had encountered at least one incident of medication error. Seven of them responded with self-intervention, and only two had reported to the appropriate senior physician.

Table 2 Characteristics of physicians involved in prescribing medications in the ICU of JUSH, April 2011 (n = 21)

Medication errors

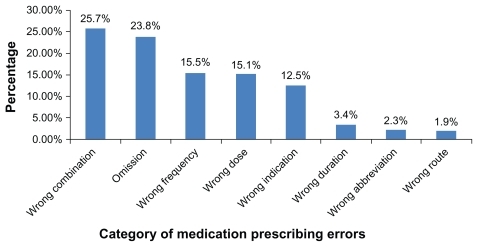

Among the 398 drug prescriptions for the 69 patients, there were 209 prescriptions containing at least one error. This constitutes a prescribing error prevalence of 52.5% during the study period (67 days). This implies that on average there were more than three prescriptions with at least one error every day in the ICU while on average only one patient was admitted per day during the same period. Out of these errors, wrong combination, frequency, and dose of drugs accounted for 68 (25.7%), 41 (15.5%), and 40 (15.1%), respectively. For 63 (23.8%) of the medications prescribed, dose/frequency/route of administration and unit of measurement were omitted ().

Figure 1 Medication prescribing error categories in the ICU of JUSH, April 2011.

Drugs with prescribing errors were classified according to their therapeutic category. Antibiotics (32.5%) and cardiovascular drugs (26.3%) were the most common categories of drugs associated with prescribing errors followed by analgesic/antipyretics (9.6%; ).

Table 3 Therapeutic category of medications with prescribing errors in the ICU of JUSH, April, 2011

Taking specific drugs into consideration, diclofenac (7.7%), ceftriaxone (7.2%), and furosemide (6.2%) were the three drugs most commonly associated with prescribing error ().

Table 4 Top ten drugs associated with prescribing error in the ICU of JUSH, April, 2011

Table 5 Examples of medication prescribing errors in the ICU of JUSH, April, 2011

Discussion

Although the definition of prescribing error did not include illegible hand writing, lack of authentication, errors associated with dosage forms, and severity of error, the findings of this study shed light on the magnitude of the problem in the ICUs of hospitals in resource-limited settings. According to this study the frequency of medication prescribing errors was 209 (52.5%). This finding is a relatively low frequency compared to the results of an earlier study involving 205 ICUs in 29 countries.Citation7 Conversely, there were higher frequencies of prescribing errors in this study than those voluntarily reported in: the intensive care and general care units in Pennsylvania in the US; a before-and-after study in a surgical ward in London; a prospective cohort study in Japan; and a multicenter prospective cohort study of seven ICUs in two hospitals in Rabat.Citation25–Citation28 The difference could be due to differences in definitions of errors, methods used to detect errors, level and type of ICUs, and availability of facilities for patient care. However, the higher frequency of errors in the ICU of JUSH even after excluding errors related with illegible hand writing, lack of authentication, and dosage form might be related to lack of sufficiently trained staff, absence of a pharmacist in the health care team, absence of a closed-loop electronic prescribing mechanism, and lack of required medical facilities in the ICU.

In this study, the most common types of medication prescribing errors were the wrong combination of drugs (25.7%), dose/frequency/route/unit omitted (23.8%), frequency (15.5%) and dose (15.1%), wrong indication (3.4%), wrong abbreviations (2.3%), and wrong route (1.9%). Omission errors, wrong indication, and wrong dose were lower than in a study from London,Citation29 probably due to low number of total errors in the other study. Frequencies of wrong dose and indication were higher than findings in a study from London while they were lower than those from Pennsylvania in the US.Citation25,Citation26 Such errors could result in toxicity/treatment failure in settings which lack therapeutic drug monitoring as is the case in our study area.

According to this study, the three most common categories of drugs encountered in prescribing errors were antibiotics (32.5%), cardiovascular drugs (26.3%), and analgesic/antipyretics (9.6%). This was different from what was reported from Pennsylvania, USA, where opioid analgesics (13.2%) were the most common category followed by β-lactam antimicrobials (8.4%) and blood coagulation modifiers (6.4%). It is also worth noting that the frequency of error among the top-rating drug categories in our study is much higher than those in the Pennsylvania study. The frequency of errors associated with opioid analgesics (5.7%) was quite low in this study and there were no errors recorded in relation to blood coagulation modifiers.Citation26 The difference might be attributed to differences in the types of cases admitted to the ICU, and comorbid conditions in the patients.

Different studies have proposed different strategies to prevent medication errors. These include optimizing the medication process, eliminating situational risk factors, oversight and error interception, and interdisciplinary teams.Citation5–Citation7,Citation30 Many studies have emphasized inclusion of the clinical pharmacist in the health care team to help to identify MEs, contribute to the rationalization of drug therapy, and potentially prevent negative consequences, leading to increased medication safety.Citation5,Citation7,Citation31,Citation32 Raising awareness of risk factors, medication reconciliation, prescribing vigilance among physicians, and good handover technique between physicians were also recommended.Citation7

Finally, it must be noted that this study did not explore the severity of errors, outcome of treatment or reasons for errors. Patients’ weight and dosage forms were often omitted from patient cards and medication charts. Illegible handwriting and prescriptions which were not signed and dated were not considered as errors. The use of guidelines rather than clinical opinions to determine error, and the small number of patients included in the study must also be noted.

In conclusion, medication errors at the prescribing phase were highly prevalent in the ICU of the JUSH. The errors reported in this study clearly show that there are multiple causes for prescribing errors in the ICU of JUSH. With the increasing complexity of care in critically ill patients, organizational factors such as the absence of quality assurance measures, error reporting systems, and routine checks could have contributed to the errors reported here. The lack of close supervision for the prescribing medical interns, along with the absence of the clinical pharmacist in the ICU team, could have made things worse. Hospital managers should strive to create better awareness about the possibility of medication errors at the prescribing phase among health care professionals. Introduction of quality assurance measures and routine checks with close supervision of the prescribing intern physicians are strongly recommended. We also recommend the inclusion of the clinical pharmacist in the health care team of the hospital in general and the ICU in particular.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CorriganJMDonaldsonMSKohnLTfor Institute of MedicineTo Err is Human: Building a Safer Health SystemWashington, DCNational Academy Press1999 Available from: www.iom.eduAccessed November 15, 2010

- Counsel of EuropePartial agreement in the social and public health fieldSurvey on medication errors112002 Available from: http://www.coe.int/t/e/social_cohesion/soc-sp/Survey%20med%20errors.pdfAccessed October 15, 2010

- ICU physician staffingFact sheetThe Leapfrog group for patient safety rewarding higher standards Available from: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/media/file/FactSheet_IPS.pdfAccessed November 15, 2010

- FahimiFSistanizadbMAbrishamiRBaniasadiSAn observational study of errors related to the preparation and administration of medications given by infusion devices in a teaching hospitalInt J Pharm Res200764295299

- WilliamsDJPMedication errorsJ R Coll Physicians Edinb200737343346

- MoyenECamiréEStelfoxHTClinical review: Medication errors in critical careCrit Care200812220818373883

- CamiréEMoyneEStelfoxHTMedication errors in critical care: risk factors, prevention and disclosureCMAJ2009180993694319398740

- BarkerKNFlynnEAPepperGABatesDWMikealRLMedication errors observed in 36 health care facilitiesArch Intern Med2002162161897190312196090

- MohamedNGabrHQuality improvement techniques to control medication errors in surgical intensive care units at emergency hospitalJ Med Biomed Sci20102435

- WilmerALouieKDodekPWongHAyasNIncidence of medication errors and adverse drug events in the ICU: a systematic reviewQual Saf Health Care2010195e720671079

- GoldsteinRSManagement of the critically ill patient in the emergency department: focus on safety issuesCrit Care Clin2005211818915579354

- Jimma University Specialized Hospital Available at: http://www.ju.edu.et/node/94Accessed on November 15, 2010

- Drug Administration and Control Authority of Ethiopia Standard treatment guidelines for general hospitals2nd edAddis Ababa, EthiopiaChamber Printing House2010

- Drug Administration and Control Authority of EthiopiaEthiopian National drug formulary1st edAddis Ababa, Ethiopia2008

- HenryGPGilbertRPHandbook of Drugs in Intensive Care: An A–Z Guide3rd edNew YorkCambridge University Press2006

- FauciASKasperDLLongoDLHarrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine17th edNew YorkMcGraw-Hill2008

- KliegmanRMBehrmanREJensonHBStantonBFNelson Text Book of Pediatrics18th edPhiladelphia, PASaunders Elsevier2007

- BerekJSBerek and Novak’s Gynecology14th edPhiladelphia, PALippincott Williams and Wilkins2006

- AndersonPOKnobenJETroutmanWGHandbook of Clinical Drug Data10th edNew YorkMcGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division2002

- SuslaGMSuffrediniAFMcAreaveyDHandbook of critical care drug therapy3rd editionPhiladelphia, PALippincott Williams and Wilkins2006

- DipiroJTTalbertRLYeeGCPharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach7th edNew YorkMcGraw-Hill, Medical Publishing Division2008

- Koda-KimbleMAYoungLYAlldredgeBAApplied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs9th edPhiladelphia, PALippincott Williams and Wilkins2009

- BaxterKStockley’s Drug Interactions Pocket Companion1st edLondon, UKPharmaceutical Press2011

- ReutersTMICROMEDEX(R) Healthcare SeriesDRUG-REAX® Interactive: Drug Interactions1974–2010146

- FranklinBO’GradyKDonyaiPJacklinABarberNThe impact of a closed-loop electronic prescribing and administration system on prescribing errors, administration errors and staff time: a before and after studyQual Saf Health Care200716427928417693676

- Kane-GillSLKowiatekJGWeberRJA comparison of voluntarily reported medication errors in intensive care and general care unitsQual Saf Health Care2010191555920172884

- MorimotoTSakumaMMatsuiKIncidence of Adverse Drug Events and Medication Errors in Japan: the JADE StudyJ Gen Intern Med201026214815320872082

- BenkiraneRRAbouqalRHaimeurCCIncidence of adverse drug events and medication errors in intensive care units: a prospective multicenter studyJ Patient Saf200951162219920434

- ShulmanRSingerMGoldstoneJBellinganGMedication errors: prospective cohort study of hand-written and computerized physician order entry in the intensive care unitCrit Care200595R516R52116277713

- WentKAntoniewiczPCornerDAReducing prescribing errors: Can a well-designed electronic system help?J Eval Clin Pract201016355655920102435

- VessalGDetection of prescription errors by a unit-based clinical pharmacist in a nephrology wardPharm World Sci2010321596519838816

- SabryNAFaridSFAbdel AzizEORole of the pharmacist in identification of medication related problems in the ICU: a preliminary screening study in an Egyptian teaching hospitalAust J Basic and Appl Sci2009329951003