Abstract

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) have been on the rise in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) over the last few decades and represent a significant healthcare concern. Over 85% of “premature” deaths worldwide due to NCDs occur in the LMICs. NCDs are an economic burden on these countries, increasing their healthcare expenditure. However, targeting NCDs in LMICs is challenging due to evolving health systems and an emphasis on acute illness. The major issues include limitations with universal health coverage, regulations, funding, distribution and availability of the healthcare workforce, and availability of health data. Experts from across the health sector in LMICs formed a Think Tank to understand and examine the issues, and to offer potential opportunities that may address the rising burden of NCDs in these countries. This review presents the evidence and posits pragmatic solutions to combat NCDs.

Graphical abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) account for 41 million (71%) of all global deaths annually.Citation1 Furthermore, around one-third of these deaths are premature (affecting people aged 30–69 years) which significantly impacts economic development and a nation’s progress.Citation2 An estimated 80% of all “premature” NCD deaths are due to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes – commonly referred to as major NCDs.Citation1 A disproportionate number of premature deaths due to NCDs occur in the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) – amounting to nearly 85% of the total global “premature” deaths due to NCDs.Citation3 The United Nations (UN) Development Program has reported the “likelihood of dying from any of the major NCDs between the age of 30–69 years” to be 60% in LMICs compared to 10% in developed nations.Citation3 As per the estimation by the World Health Organization (WHO), NCDs will be responsible for seven out of 10 deaths in LMICs by 2020.Citation4

Globally, mental disorders are associated with greater disability than any of the physical conditions,Citation5 and 75% of suicides occur in LMICs.Citation6 Yet, mental health issues are poorly addressed in LMICs largely due to the impact of stigma related to mental health.Citation7 The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target 3.4, that specifically relates to NCDs, is for a one-third reduction in premature deaths from the four major NCDs and promotion of mental health and well-being by 2030 (relative to 2015 levels).Citation8 Most of the LMICs are unlikely to meet this target for 2030.Citation9 In 2011; the World Economic Forum concluded that NCDs would incur losses of $21.3 trillion in developing countries over the next two decades.Citation10 Among all LMICs, the upper-middle-income countries would contribute to most of the cost as their populations and economies would continue to grow, and their populations would age more rapidly.Citation2 This cost is much higher than the cost of instituting preventive measures. Thus, especially in LMICs, inaction towards NCDs is unacceptable and the cost of inaction far outweighs the cost of action.Citation11

The United Nations High Level Meeting (UNHLM) held during the UN General Assembly in 2014, which focused on non-communicable diseases (NCD), emphasized the need for strengthening health systems, prioritizing NCDs, and engaging the private sector to prevent and control NCDs.Citation12 Embracing the role of the private sector, Pfizer launched Upjohn in 2018 as a division dedicated to the fight against NCDs through a focused, strategic, and collaborative approach across the healthcare value chain.Citation13

When gathering insights that would inform appropriate interventions, Upjohn found considerable variability in the burden of NCDs across nations and in corresponding preparedness to deal with it. No country has yet completed all the requirements to be in full readiness to combat NCDs. This insight was the key driver to establishing a Think Tank, the Expert Forum on NCDs in Emerging Nations. The objective was to provide further granularity – (a) review the impact of NCDs in low- and middle-income countries, (b) explore the challenges to combating them and (c) offer pragmatic solutions.

In association with leading NCD combatants in Latin America, the Middle East and Asia, actors from LMICs in these regions who are involved in NCDs from frontline clinicians in public health and private practice, civil society, academia, health technology, public policy and patient advocacy were invited to the Think Tank. The selection was based on publicly available knowledge of their work on NCDs, recognition by their peers, an expressed desire to be a change-agent and, to quote Richard Horton, Editor-in-Chief of The Lancet, not be “too polite to make the impact it (the NCD movement) deserves”.Citation14 Any observation or assertion made by individuals on the Think Tank, on the objectives were supported by evidence in the literature or qualified as personal communication.

Upjohn’s approach was clearly aligned with the 2019 UNHLM acknowledgement of the significance and complexity of NCDs, and the challenge for governments to work alone in managing them. Along with a call to further strengthen efforts to address non-communicable diseases, the UNHLM fostered public- and private-sector collaborations.Citation15

The Expert Forum on NCDs in Emerging Nations was convened in Dubai in late 2019. We report on the deliberations of the Think Tank and describe some practical solutions offered to tackle NCDs in LMICs. It adds a unique, multisector perspective and consensus to the growing body of work on the challenges and solutions to reduce the burden of NCDs in LMICs.

Assessment of NCD Burden in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

Epidemiology

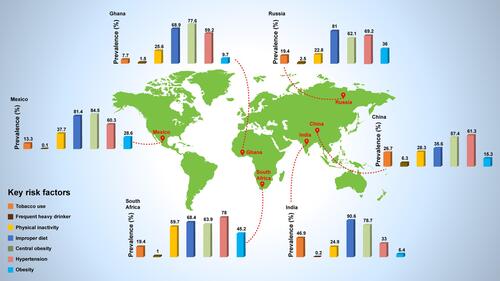

In 2018, the UN outlined a 5 × 5 model to address the NCD burden across LMICs. It identified five disease areas – CVDs, chronic respiratory diseases, cancer, diabetes, and mental and neurological conditions, that are related to five key preventable risk factors – unhealthy diet, tobacco, excessive alcohol, physical inactivity, and air pollution.Citation5 However, there is increasing data to suggest that the effect of risk factors varies between different populations.Citation16 For example, studies conducted in the UK showed that people who persistently smoke, have a three-fold higher risk of death from lung cancer, whereas in China, the risk of mortality was only double.Citation17–Citation19 Long-term, population-specific data are necessary to identify critical areas to target with appropriate intervention in individual countries.Citation16 depicts the prevalence of various risk factors across several LMICs in Asia, Africa and Latin America. In the Middle East, there are also wide variations in the prevalence of NCD risk factors across countries.Citation20 Prevalence rates for obesity are higher in the more affluent Middle Eastern countries while smoking is more prevalent in Lebanon (55.8%), followed by Jordan and Syria.Citation20

Figure 1 Prevalence of key risk factors among persons aged >50 years in selected low- and middle-income countries.

Notes: Data compiled from Wu et al, 2015.Citation16 Use of tobacco varies considerably from 7.7% in Ghana to 46.9% in India.Citation16 Although the prevalence of tobacco smoking is declining in most countries, tobacco use is increasing in the African Region.Citation16,Citation108 Consumption of alcohol is highest in China (6.3%) and considerably lower in India and Mexico.Citation16 However, alcohol use has increased drastically in Mexico since 2011, especially in women.Citation109 Obesity is more common in South Africa, Russia and Mexico compared to China, India and Ghana.Citation16 As per the “Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development” 2017 report, Mexico had the highest prevalence of obesity in the population aged 15–74 years (32.4%).Citation110 Prevalence of hypertension varied from 33% (India) to 78% (South Africa).Citation16

Macroeconomic Status

The cost of healthcare is rising more rapidly in most countries, than their economic growth, leading to an essential requirement for “value-based healthcare” (VBHC). This concept enables countries to adopt value-based approaches for their health systems to deliver improved care by the best use of limited resources.Citation21 In 2016, a landmark studyCitation21 was conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) across 25 nations. It examined the alignment of health systems across four main domains of value-based healthcare consisting of 17 qualitative indicators. The four domains included – (1) “policy and institutions” within which the health systems operate to capture the level of commitment to value-based healthcare; (2) “metrics for measuring outcomes and costs” that capture the existence of the data collection and infrastructure within a health system; (3) “integrated and patient-focused care pathways” that capture a nation’s efforts to integrate care; and (4) “outcome-based payments approach” that measures the extent of moving away from paid services. Some LMICs have aligned with these components, whilst many are finding them challenging.Citation21 Key challenges include enabling access to healthcare, improving the quality of care and decreasing the costs.Citation22 There is a shift in focus from access to health systems towards the quality of health systems, and the pressure is increasing on LMICs to innovate domestically.Citation21 Also, a change in perspective from “sick-care” to “health and wellness” is necessary, whereby solutions are focused on root-cause and preventative care.

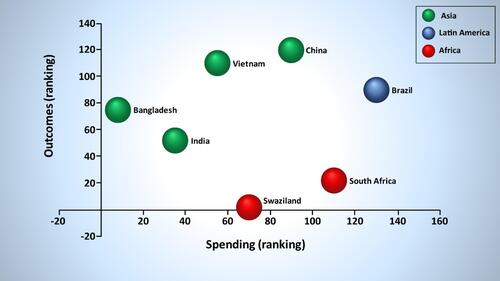

It is believed that a close relationship exists between healthcare spending and outcomes. As countries begin to invest more, better outcomes are observed.Citation23 However, the determinants of good outcomes are not based just on investment. illustrates a study by EIUCitation24 comparing healthcare outcomes and expenditure in several countries. Stark disparities in spending and outcomes are observed in certain LMICs. Countries like Bangladesh, which spend very little in comparison to others and still generate good outcomes, need to be studied to understand the underlying reasons for their success and efficiency. Similarly, countries such as eSwatini (formerly Swaziland) that are not generating good outcomes, despite spending large sums of money should also be studied to identify and overcome any challenge.Citation24 A recent study from the Eastern Mediterranean Region has confirmed that high total health expenditure with high rates of out-of-pocket expenses leads to poorer financing performance of a country and does not improve its financing status.Citation23

Figure 2 Healthcare expenditure and outcomes in low- and middle-income countries.

Notes: The EIU studyCitation24 compared healthcare outcomes and spending in 166 countries. “Disability Adjusted Life Years” and “Health-Adjusted Life Expectancy” were used as the main indicators to measure healthcare outcomes along with “average life expectancy at age 60” and “adult mortality rates”. A composite index score was generated from all the four indicators (higher scores indicate better healthcare outcomes). The countries were ranked based on healthcare outcomes (with 166 being the best) and spending per head (with 166 being the most expensive).Citation24

Social Development

Increasing incomes, access to digital and mobile platforms, and better health literacy are placing a higher demand on health systems. Furthermore, a globally aging population with longer life expectancies and an increasing number of risk factors and comorbidity is placing higher demands on existing health systems.Citation25 And yet, resources for improved health systems remain mostly stagnant and are definitely not growing in parallel with the aging population.Citation21

To bridge the NCD healthcare gap between LMICs and developed nations, a value-based sustainable healthcare system is needed that goes beyond therapeutics and addresses issues along all stages of the patient journey (covering not only diagnosis, treatment, and adherence to therapy but also prevention and screening for lifestyle and metabolic risk factors).Citation26 Many countries are leading innovative initiatives towards value-based healthcare; however, the sustainability and scalability of these efforts need to be assessed.Citation21

Challenges in Combating NCD Burden in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

The first UN High-Level Meeting on prevention and control of NCDs was held in 2011, with WHO member states committing to reduce mortality due to NCDs by 25%.Citation8 The second UN High-Level Meeting held in 2014 reaffirmed the political declaration and recognized mental health as an important contributor to global NCD burden. The need for implementing multisectoral strategies for managing the NCD burden were further reiterated.Citation12 The progress by member nations was reviewed at the third UN High-Level Meeting held in 2018, which concluded that the progress was not adequate to meet the expected goals. Several key challenges were identified including need for stronger health systems, improved access to healthcare and need for adequate and well-trained workforce.Citation27

Low Prioritization of Healthcare

Prioritization of prevention and management of NCDs in LMICs competes with a variety of other important priorities, eg, combating poverty, access to clean water, housing, education, gender equality, etc. This is further complicated by existing models of health systems in LMICs designed for acute health conditions, which are economically unsustainable for the management of chronic diseases.Citation28,Citation29 Many of the LMICs are not providing basic NCD interventions in primary care – driving patients to private healthcare with heavy out-of-pocket expenses and worsening of poverty.Citation30 Also, the political, social, environmental, and economic frameworks are generally not structured for health-promoting behaviors in LMICs.Citation28

The various challenges faced by LMICs in combating the NCD burden can be divided into five major categories () and are explored below.

Limited Implementation of Universal Health Coverage

In 2015, all member nations endorsed the SDGs by UN with a commitment to universal health coverage (UHC) to achieve these goals.Citation3 Further, under the stewardship of the WHO, governments agreed on globally accepted targets to measure the performance of their health systems. Targets emphasized the role of high-level political commitment and government action to reduce premature deaths due to NCDs by 25% by the year 2025.Citation31 It also entailed ensuring that target level for the availability of the essential NCD medicines is at least 80%Citation32 and that at least 50% of eligible patients receive drug therapy and counselling to prevent heart attacks and strokes.Citation31 The first United Nations High-Level Meeting (UNHLM) on UHC held in New York on 23rd September 2019Citation33 emphasized that primary healthcare is the cornerstone of strong and equitable healthcare and countries need to invest in a primary care strategy.Citation15 It was mandated that healthcare should be people-centric and primary healthcare should prioritize NCDs.Citation15

However, the implementation of these strategies faces several barriers, including limitations in human resources, finances, acceptability and sustainability. Policies are easier to implement in countries where an established primary healthcare system is in place. This entails prior investment in healthcare, good legislation, well-trained staff, a strong health system including good infrastructure, and access to medicines.Citation34 Thus, in countries like Sudan, inequality in access and the quality of the health system are significant barriers to care. Despite low rates of diabetes in Sudan when compared with other LMICs, the rate of complications is relatively high due to its limited healthcare budget and access to medicines.Citation35 Refugees’ and migrant families without medical records, coupled with the unavailability of free medicines place further demands on healthcare.Citation36 For example, in 2015, the refugee population represented almost one-third of the total population in Lebanon, and a fragmented and uncoordinated healthcare system is unable to cope with the humanitarian crisis in that country.Citation37

Though few Southeast Asian Nations have made good progress towards UHC,Citation38 there remains a tremendous gap on the coverage of services related to NCDs.Citation39–Citation42 According to recent estimates from the WHO, healthcare spending pushes at least 65 million people into poverty every year in Southeast Asia.Citation43

Need for Regulations Governing NCD Risks

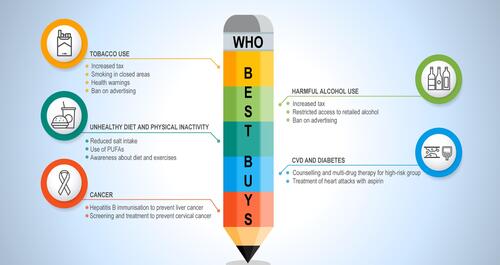

The WHO has identified “Best Buys”, which are evidence-based, cost-effective interventions targeting tobacco use, harmful alcohol use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, CVD, diabetes and cancer ().Citation44 The cost for a scaled-up implementation of these “best buys” strategies is quite low. In health gains, the return on the investment is many millions of avoided “premature” deaths, and for a nation’s economy, the return is several billions of dollars.Citation45

Figure 4 “Best Buys” identified by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Notes: The Best Buy recommendations by WHO aims to encourage a healthy lifestyle by imposing restrictions on access and increasing excise on alcohol and tobacco and supports the education of the public regarding a healthy lifestyle and primary prevention of NCDs.Citation44 The cost for a scaled-up implementation of these “best buys” strategies is quite low. In health gains, the return on the investment is many millions of avoided “premature” deaths, and for a nation’s economy, the return is several billions of dollars.Citation45

Abbreviation: PUFAs, polyunsaturated fatty acids.

While governments in many LMICs have committed to WHO guidelines and have enacted various tobacco-related laws in place (eg, taxes on cigarettes, smoking in closed areas), inadequate enforcement of some measures reduces their impact.Citation46 For example, in Lebanon, smoking is strictly prohibited in indoor public places. However, the laws are frequently violated without penalty, and public smoking is often allowed, especially in restaurants and bars.Citation47 Sugar and alcohol taxes have been imposed in a few countries; there is also a move to reduce added salt and fat and legislative measures to reduce unhealthy oils. However, these attempts are sparse, require a centralized government approach and are difficult to implement. Environmental pollution and safe spaces for physical activity have meagre investments, the majority of countries still use fossil fuels, and ambient and household air pollution are still among the major causes of deaths in LMICs.Citation48 Additional support is needed to plan and implement policies and regulations in LMICs effectively.Citation49 Despite a commitment towards UHC and to address NCDs; the policies remain underdeveloped or not implemented. Even with policies being in place in many LMICs, enforcement and accountability have been wanting.Citation49 Transparency and availability of data in the public domain for monitoring and tracking may assist in change for the better.

Unequal Distribution of Health Workforce

The key barriers to care in LMICs include not only access to healthcare but also the availability and gaps in the education of health providers.Citation50 Quality of care is diminished due to large patient volumes and a low health providers to patient ratio.Citation22,Citation51,Citation52 Working conditions, work burden and burnout of the health workforce also affect their performance, motivation and efficiency.Citation22,Citation50,Citation52,Citation53 Retention of health workers especially in remote and rural areas remains a key challenge in LMICs.Citation51

Additionally, a lack of incentives for health providers to promote NCD issues and preventive healthcare remains a challenge. Given the limited budgets, many health systems have a “fire-fighting” approach and can only address acute illnesses.Citation54

Need for Intersectoral Partnerships

At the UN High-Level Meeting in 2019,Citation28 NCDs were acknowledged as significant and complex issues that cannot be properly addressed by governments alone.Citation29 The meeting called for civil societies to play a key role in highlighting NCDs, and voiced the need for public- and private-sector partnerships.Citation55

Gaps exist when translating scientific knowledge into effective policies with the scientific community and policymakers tending to exist in silos. To support change in policy, it is essential to conduct a stakeholder analysis to understand where capabilities and resources lie and to define priorities.Citation56 While the WHO has outlined a large number of strategies to improve healthcare in LMICs, it is crucial to consider accessibility and affordability of these in each country before their implementation.Citation57

The fear of the impact on cross-border security and trade generates significant immediate public health responses to communicable disease outbreaks like EbolaCitation58 and COVID-19.Citation59 However, despite the huge impact of NCDs, a similar response is not readily forthcoming.Citation28,Citation60 Broadening the framing of health security to include NCDs has been suggested.Citation58

Intersectoral partnerships across government, industry, and professional and civil societies may help to effectively address these challenges and reduce the NCD burden in LMICs. Such alliances would be useful to shape policies and to improve healthcare and patient outcomes.Citation55

Gaps in Systematic Data Collection and Longitudinal Surveillance Data

Public health surveillance refers to “the continual systematic collection, recording, and analysis of health data for the planning, execution and assessment of public healthcare practice”.Citation61

The Global Burden of Disease StudyCitation62 now includes data from almost every country in the world. However, a significant proportion of the information is based on data-modelling due to gaps in data from individual countries. Despite significant improvements in the last 20 years, these gaps still exist.Citation62

Longitudinal surveillance data can define the scope of public health problems due to NCDs to enable the development of evidence-based solutions.Citation22,Citation63 Multiple methods may be required to collect essential information for effective NCD surveillance.Citation64 Many cross-sectional studies have been undertaken in different countries, including the WHO STEPS survey.Citation64 However, prospective cohort studies which help to understand the interaction of multiple risks and their impact on healthcare outcomes are few.Citation63,Citation64

Systemic Solutions for Tackling NCDs in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

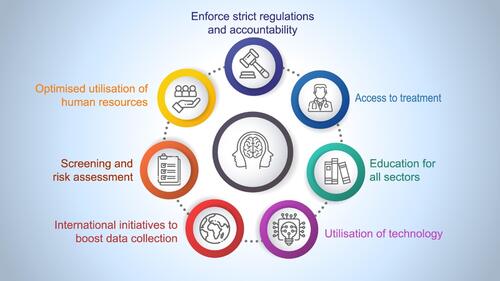

Health systems require the evidence and then governance and leadership to implement the best possible health initiatives, policies, along with ongoing surveillance for monitoring the performance of such initiatives.Citation28 The stage of development of a country as well as their priorities should be considered while determining the most cost-effective interventions for that particular nation.Citation65 The comparative and historical experiences of countries are an important consideration when reviewing data and responses. Effectiveness of interventions may vary in different countries, and several factors such as politics, religion and culture should be considered when translating an intervention from one country to another.Citation30 summarizes some of the proposed solutions for tackling NCDs in LMICs.

Figure 5 Think Tank Proposed Solutions for tackling NCDs in low- and middle-income countries.

Notes: “Screening and risk assessment”, “optimised utilisation of human resources” and “education for all sectors” along with “utilisation of technology for inadequate effective health workforce” can help to fill in the gaps created by insufficient “effective health workforce availability and distribution” in LMICs. “Access to treatment” and “public–private partnerships” can bridge the gaps in the “universal health coverage” in LMICs. “Enforcing strict regulations and accountability” is the key solution for “gaps in the implementation of regulations” seen in most LMICs. “International initiatives to boost data collection” as well as “screening and risk assessment” can boost “systematic data collection and longitudinal surveillance data in LMICs”

Screening and Risk Assessment

Asymptomatic and high-risk patients may not present to primary healthcare, and preventative measures should be considered for such cases.Citation44 While it is better to have population-specific risk assessment tools, these require good-quality long-term local outcomes data. International risk assessment tools, validated using available datasets in LMICs, could be utilised.Citation66

The WHO has set the foundation for major NCDs screening and risk assessment guidance for LMICs.Citation67 The WHO-STEP survey can be used to collect data on NCDs and associated risk factors. Additionally, the STEP survey also calculates the total risk factor for the population as a percentage of the number of people in the community with comorbidities and multiple risk factors.Citation68 The WHO risk prediction charts were recently implemented in the Philippines in the “E-Sakto study” and demonstrated a reduction in the 10-year CVD risk in the target population.Citation69

Optimized Utilization of Human Resources

NCD prevention and treatment require the integration of care between hospitals and the community. Healthcare providers like pharmacists and nurses are often not utilized effectively. “Task-shifting” refers to these healthcare providers and, to health workers who are coached and trained, performing and executing certain activities that are traditionally undertaken by physicians.Citation52,Citation70 Utilizing community health workers (CHWs) and trained peers increase the outreach of the health system and reduce the burden on the clinicians.Citation71 “Task-shifting” from physicians to CHWs through re-configuring of the health system is a potentially effective and affordable strategy for combating NCDs in LMICs.Citation52,Citation70

However, implementation of a multi-component strategy, which can monitor health trends and accumulate data require the cooperation of clinical (for diagnosis and treatment) and non-clinical personnel (for evaluation, engagement and empowerment).Citation22,Citation52 Further, in addition to adequate finances and resources, policies, and a skilled workforce augmented with incentives are needed to achieve optimal outcomes.Citation29 To reach this goal, strengthening of governance and accountability; coordination of services within and across sectors; and the creation of an enabling and supportive environment for health providers, including incentives for supporting remote/rural areas is required.Citation22,Citation29,Citation63,Citation72

In countries like Lebanon, community pharmacies have been acting as a point of care for testing and screening for many NCDs.Citation73 The NCD e-module was developed on their Health Information System to aid the centers collect NCD-related data and calculate the CV risk.Citation74 Community pharmacists are implementing initiatives with the support of private pharmaceutical companies and are also responsible for the management of NCDs by improving treatment adherence, empowering patients and families, and counselling them on medical therapy and lifestyle interventions.Citation73 However, despite being available free of charge, these services remain underutilized due to a lack of education and patient inhibitions.Citation75 This also demonstrates the need for patient representation when discussing and implementing NCD care.

Enforcement of Regulations and Accountability

WHO “best buys” are voluntary and governments can choose to adopt any of the proposed policies. Although, all countries should aspire to execute the WHO “best buys”,Citation44 currently most countries will not achieve their targets (eg, 50% reduction in tobacco use) even though it could provide countries with tangible goals that represent progress in the right direction.Citation9 Conflict of interest between different sectors often creates challenges for the successful implementation of policies. In these cases, civil societies and patient groups can play an essential role in the execution of these measures.Citation76

Strategies for implementation of behavior changes need to vary based on environmental differences. Data from Western countries suggest that health awareness does not necessarily elicit a shift in behavior, whilst taxation or other incentives may be more successful.Citation77 Tobacco, alcohol and unhealthy diets play a significant role in NCDs. In Western countries, the reduction in tobacco use was primarily driven by increased taxes, regulations, and reduced advertising, as opposed to education and awareness. For example, smoking rates halved when taxes on tobacco were doubled in France.Citation78 In Latin America, Brazil has implemented many cross-sectoral measures to control tobacco use, including taxes on cigarettes, which are leading to a significant reduction in smoking in the country (around 35% in 1989 to around 11% in 2013).Citation79,Citation80 However, the most successful implemented strategy was the change in the social acceptability of tobacco use and creation of “tobacco-free environments” which went from being implemented in the 1980s–1990s to being broadly consolidated in the 2000s.Citation79

Implementation of Sin Tax in the Philippines, which increased taxes on cigarettes and alcohol effectively reduced cigarette and alcohol consumption in the country.Citation81 While there has been some success in controlling NCDs through initiatives addressing unhealthy diets, taxes, this time on sugar-sweetened drinks, have again been shown to be most effective in countries like Mexico and Chile.Citation82

Further to establishing regulations in LMICs, enforcing them is a key challenge. For example, the food industry is very influential in many countries and remains a significant barrier to effectively implement and maintain interventions that target unhealthy diets.Citation76 These industries need to be part of the solution.

Civil society, private sector, and patient groups can help foster accountability by monitoring strategies and interventions. Sustainable Development Goals and their targets, and other targets for NCDs may help accountability in countries as they are regularly monitored and benchmarked.Citation76

A suggestion to address the multi-level implementation gap is the formation of a consortium of healthcare experts with the following operational guidance:

Rotating leadership (perhaps between regions or countries).

Elect a steering committee.

Invite expert panels that regularly renew with fresh contributors.

Be close to policymakers.

Tap into networks such as the Geneva Health Forum.

Uniform Access to Treatment

The WHO has developed a Package of Essential NCD interventions (PEN) for primary care in low-resource settings with the aim of providing cost-effective care for NCDs. The package includes tools that aid early diagnosis and management of NCDs.Citation83 Governments need to allocate a certain percentage of gross domestic product for tools such as PEN to combat NCDs; however, this can be difficult in LMICs.Citation21 Much of their health spending tends to be financed through development assistance for health (DAH), in comparison to wealthier nations. In 2018, total DAH was $38.9 billion. However, less than 1% was allocated to NCDs.Citation84 There is a need for public–private partnerships, at least to make avail of packages like PEN. Many public–private partnerships have successfully demonstrated the catalysis of prevention, access and delivery of care for communicable diseases by providing complementary strengths.Citation85 Perhaps these models of partnership have the potential to transform the existing solutions in combating NCDs in LMICs.

Education for All Sectors and the Inclusion of Patients

A multi-component strategy is needed to tackle the complex interactions between physical, psychosocial and behavioral factors.Citation22 The stigma associated with mental health, for example, is not limited to patients but also impacts healthcare providers resulting in low rates of screening.Citation86 With limited resources to spend on healthcare, LMICs need to prioritize critical areas for investment, which can offer maximum impact. A holistic approach to the training of healthcare providers should be adopted, taking into account critical risk factors, lifestyle modifications, psychotherapy, nutrition and physical activity.Citation57 Ongoing patient education and family engagement is also vital—in presence of shortage of health providers, digital and mobile health technology can be used to convey and reinforce information to patients and caregivers.Citation87–Citation89 Cost-effective health education should penetrate the targeted populations in remote areas with low health resources and among people, with poor education.Citation90 Active involvement of youth in health education is recommended as they have the most access to technology and may serve to influence their communities towards better health practices. Health messages also must be translated into local language or dialects and to effectively train patients as well as caregivers.

Standards of care can vary for different health conditions with varying guideline recommendations from different associations. This often leads to confusion among patients who receive conflicting information from various health providers.Citation91,Citation92 There remains a major need to bridge the gap between physicians, nurses and pharmacists to ensure consistency in what is shared with patients. Patients are often thought of as recipients of care, but they can also be equal participants. There is increasing recognition of expert patients contributing to knowledge and resource pools.Citation93 Initiatives via professional societies could help to support education, information sharing and patient empowerment. Sustainability of these initiatives is the biggest challenge; there is a good opportunity for the private sector to provide funding.Citation94,Citation95

With ready access to the internet on mobile devices, patients are no longer passive recipients of care. Patients are increasingly assuming the role of health consumers with autonomy, demanding health information and the ability to choose. They are also an essential component of the healthcare system and need to start taking more responsibility.Citation93 This may be accomplished by providing them with the tools to become part of the healthcare system supply chain.

Utilization of Technology

Social media plays a key role in improving patients’ awareness of diseases and helping patients find the relevant physician, clinic or hospital for their symptoms.Citation96 However, it is important to acknowledge that social media can have negative effects by propagating misinformation (eg, miracle cures).Citation96 There is a need for a source of credible information in layman’s language, which can be easily accessed by the patient. For instance, just as physicians turn to the Centers for Disease Control for trustworthy information, patients too need a similar source of reliable information. Technologies can also be used to address the challenges faced in relation to NCDs.Citation97 For example, a number of countries have begun to use technology to facilitate communication between patients and care providers through “virtual clinics”.Citation98 Currently available applications of continuous glucose monitoring in diabetes can successfully alert and track patients in relation to blood glucose levels.Citation99

A multichannel mHealth platform deployed in many countries includes an automated clinical decision triage that allows patients to access medical helpline remotely.Citation100,Citation101 A clinical trial utilizing this intervention has demonstrated improved adherence and clinical outcomes with patients reporting high levels of satisfaction with the intervention.Citation98 The Dia360 interventionCitation102 is a similar project which was developed in collaboration with the Diabetes Association of Bangladesh. The application aims to improve adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes through health educational content, phone-based consultations and mobile messaging by physicians trained in diabetes management to facilitate behavior change and remind patients for follow-up appointments.Citation102 The E-SaktoCitation69 program in the Philippines has integrated technology into rural healthcare with community healthcare workers measuring, student volunteers uploading and clinicians monitoring patients’ risk factors. CHWs conduct monthly health training on lifestyle tips and health information to registered patients and their families on a monthly basis (Community Health Club).Citation69

Mobile infrastructure currently reaches 5 billion people worldwide,Citation100 providing an opportunity for new platforms for patient and healthcare provider engagement, coordination of care and disease prevention.Citation103 The scope may vary from training health providers on the latest clinical recommendations, disease management best practices, creating automated workflows for healthcare delivery as well as leveraging patient data to build predictive algorithms.Citation87–Citation89 Beyond clinical interventions, the financing of healthcare also needs to find sustainable solutions – new initiatives aimed at reducing out-of-pocket health spends and others aimed at accelerating UHC, are required.Citation104

While some of these interventions were successful, driving change and engagement at the front end of the patient journey and delivering deep integration into provider tools and workflows remains a challenge. Three key components need to be considered while looking at core capabilities to implement change – (1) health engagement and behavioral change for the patient; (2) improvement in the outreach of primary care and provider networks; and (3) health insurance and payments to ensure sustainability.

International Initiatives to Boost Data Collection

Data for the burden of disease and antecedent risk factors from cross-sectional surveys do exist for many LMICs, but gaps exist in long-term prospective data and understanding the interactions among risk factors.Citation65 A high level of data is available for a significant portion of the population in the developed nations because of integrated healthcare systems in these countries.Citation105 Highly committed international initiatives are required to enhance data collection in LMICs.Citation106 However, prospective data collection requires a lot of time, effort and investment. Hence available local data, even from smaller studies, should be shared with policymakers for immediate action.Citation30 In the Middle East, Iran is taking the lead in prospective cohort studies and clinical trials, exemplified by a recently published polypill study.Citation107 However, rather than waiting for the study results, changes should occur in parallel with the progress of studies.Citation29 In the absence of prospective cohort studies, other sources of data such as health insurance records may be utilized to gather the required information.

Conclusion

The Expert Forum acknowledged the challenges faced by governments in managing NCDs and the need for public- and private-sector collaborations to achieve targeted outcomes.

Under the stewardship of the WHO, many LMICs are trying to achieve the SDG target 3.4 through UHC. However, even though governments are making progress to improve access to treatment and instituting regulations for healthy lifestyles, many are finding it challenging to implement policies, devote adequate funds and engage human resources for healthcare. Access to safe and quality management of NCDs is determined by a combination of factors including geographical and financial access, health literacy, availability of essential medicines, skilled workforce and an enabling environment that fosters risk screening. Sharing of data collected from screening programs can help to understand the feasibility and design of interventions and policies. The spread of mobile telecommunications and technology should be tapped to improve access and delivery of healthcare, especially to remote areas in LMICs. A multisectoral approach with novel accountable alliances involving key stakeholders from both public and private sectors is needed to ensure that the essential resources for NCD care are evenly distributed and accessible to all, particularly for those who need it the most.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Phua Kai Hong, Health and Social Policy, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, Singapore for his valuable insights during the Expert Forum meeting, which were critical for drafting this article. The authors sincerely appreciate the medical writing support provided by Dr Sajita Setia, Executive Director, Transform Medical Communications, Auckland, New Zealand, and editorial support provided by Dr Veena Angle, Singapore on behalf of Transform Medical Communications.

Disclosure

This article is based on the dialogue that occurred at the “Expert Forum on NCDs in Emerging Nations” convened by Pfizer in Dubai, UAE, 27–28 September 2019 and attended by all authors. Honoraria were provided by Pfizer to the external experts for their attendance at the meeting No author received an honorarium for the preparation of the article. Dr Amrit Ray, Dr Anurita Majumdar, Dr Barrett W Jeffers, Dr Kannan Subramaniam and Dr Shekhar Potkar are employees of Pfizer. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent or reflect in any way the official policy or position of their current or previous employers. Editorial and medical writing support was provided by Transform Medical Communications, which was funded by Pfizer.

Mr Mathew Guilford reports personal fees from Common Health, Inc., during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Pfizer Upjohn, outside the submitted work. Dr Raghib Ali reports personal fees from Pfizer Upjohn, grants from Pfizer Upjohn, outside the submitted work. Dr Rayaz A Malik has attended advisory board to discuss NCD’s by pfizer, during the conduct of the study; and received grants from Pfizer, grants to support a consensus meeting on neurodegenerative disease from Biogen, personal fees from Novo Nordisk, personal fees from Aventis, outside the submitted work.

References

- Non communicable diseases [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- The Global Economic Burden of Non-communicable Diseases [homepage on the internet]. Geneva: World Economic Forum. World Economic Forum. Available from: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Harvard_HE_GlobalEconomicBurdenNonCommunicableDiseases_2011.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Guidance note on the integration of noncommunicable diseases into the united nations development assistance framework [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/nmh/ncd-task-force/guidance-note.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2019.

- Islam SM, Purnat TD, Phuong NT, Mwingira U, Schacht K, Fröschl G. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in developing countries: a symposium report. Global Health. 2014;10. doi:10.1186/s12992-014-0081-9

- Stein DJ, Benjet C, Gureje O, et al. Integrating mental health with other non-communicable diseases. BMJ. 2019;364:l295. doi:10.1136/bmj.l295

- Mental Health and Neurological Disorders [homepage on the internet] NCD Alliance. Available from: https://ncdalliance.org/why-ncds/ncd-management/mental-health-and-neurological-disorders. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Mascayano F, Armijo JE, Yang LH. Addressing stigma relating to mental illness in low- and middle-income countries. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6(38). doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00038

- Bennett JE, Stevens GA, Mathers CD; NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators. NCD Countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1072–1088. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5

- NCD countdown 2030 [homepage on internet]. Available from: http://www.ncdcountdown.org/. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- What legislators need to know [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/HIV-AIDS/NCDs/Legislators%20English.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Allen LN. Financing national non-communicable disease responses. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1326687. doi:10.1080/16549716.2017.1326687

- Outcome document of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Comprehensive Review and Assessment of the Progress Achieved in the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases [homepage on the internet]. UN General Assembly; 2014. Available from: http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/774662/files/A_68_L.53-EN.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Leading the Conversation on Noncommunicable Diseases Worldwide: an Evidence-Based Review of Key Research and Strategies to Develop Sustainable Solutions [homepage on internet]. Pfizer Upjohn. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/upjohn_ncd_white_paper. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Horton R. Offline: chronic diseases—the social justice issue of our time. Lancet. 2015;386(10011):2378. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01178-2

- Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage [homepage on the internet]. Available from: https://www.un.org/pga/73/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2019/07/FINAL-draft-UHC-Political-Declaration.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Wu F, Guo Y, Chatterji S, et al. Common risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases among older adults in China, Ghana, Mexico, India, Russia and South Africa: the study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE) wave 1. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):88. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-1407-0

- Parascandola M, Xiao L. Tobacco and the lung cancer epidemic in China. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(Suppl 1):S21–S30. doi:10.21037/tlcr.2019.03.12

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE

- Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V. Million Women Study Collaborators. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381(9861):133–141. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6

- Sibai AM, Nasreddine L, Mokdad AH, Adra N, Tabet M, Hwalla N. Nutrition transition and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Middle East and North Africa countries: reviewing the evidence. Ann Nutr Metab. 2010;57(3–4):193–203. doi:10.1159/000321527

- Value-based healthcare: A global assessment [homepage on the internet]. Economist Intelligence Unit. Available from: https://perspectives.eiu.com/sites/default/files/EIU_Medtronic_Findings-and-Methodology_1.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Chan JC, Lim LL, Luk AO, et al. From Hong Kong diabetes register to JADE program to RAMP-DM for data-driven actions. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(11):2022–2031. doi:10.2337/dci19-0003

- Pourmohammadi K, Shojaei P, Rahimi H, Bastani P. Evaluating the health system financing of the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) countries using Grey Relation Analysis and Shannon Entropy. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2018;16(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12962-018-0151-6

- Health outcomes and cost: A 166-country comparison [homepage on the internet]. Economist Intelligence Unit. Available from: https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=Healthoutcome2014. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- Arokiasamy P, Uttamacharya U, Jain K, et al. The impact of multimorbidity on adult physical and mental health in low- and middle-income countries: what does the study on global ageing and adult health (SAGE) reveal? BMC Med. 2015;13(1):1–16. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0402-8

- Adair T. Progress towards reducing premature NCD mortality - The Lancet Global Health. Lancet. 2018;6(12):E1254–E1255.

- 2018 United Nations High-Level Meeting on Non-communicable Diseases [homepage on the internet]. ESMO. Available from: https://www.esmo.org/policy/world-health-organization-united-nations/united-nations-high-level-meetings/2018-United-Nations-High-Level-Meeting-on-Non-communicable-Diseases. Accessed May 26, 2020.

- Allotey P, Davey T, Reidpath DD. NCDs in low and middle-income countries - assessing the capacity of health systems to respond to population needs. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(2):1–3. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-S2-S1

- Tham TY, Tran TL, Prueksaritanond S, Isidro JS, Setia S, Welluppillai V. Integrated health care systems in Asia: an urgent necessity. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:2527–2538. doi:10.2147/CIA.S185048

- Mendis S. The policy agenda for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. Br Med Bull. 2010;96(1):23–43. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldq037

- Know the NCD targets [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/beat-ncds/take-action/targets/en/. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Wirtz VJ, Kaplan WA, Kwan GF, Laing RO. Access to medications for cardiovascular diseases in low- and middle-income countries. Circulation. 2016;133(21):2076–2085. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.008722

- UN High-Level Meeting on universal health coverage [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2019/09/23/default-calendar/un-high-level-meeting-on-universal-health-coverage. Accessed October 28, 2019.

- Universal health coverage (UHC) [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc). Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Bos M, Agyemang C. Prevalence and complications of diabetes mellitus in Northern Africa, a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):387. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-387

- Kotsiou O, Kotsios P, Srivastava D, Kotsios V, Gourgoulianis K, Exadaktylos A. Impact of the refugee crisis on the Greek healthcare system: a long road to Ithaca. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(8):1790. doi:10.3390/ijerph15081790

- Blanchet K, Fouad FM, Pherali T. Syrian refugees in Lebanon: the search for universal health coverage. Confl Health. 2016;10(1):1–5. doi:10.1186/s13031-016-0079-4

- Van Minh H, Pocock NS, Chaiyakunapruk N, et al. Progress toward universal health coverage in ASEAN. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):25856. doi:10.3402/gha.v7.25856

- Noncommunicable diseases and mental health: south East Asian Region [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/nmh/ncd-tools/who-regions-south-east-asia/en/. Accessed October 25, 2019.

- Myint CY, Pavlova M, Thein KN, Groot W. A systematic review of the health-financing mechanisms in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations countries and the People’s Republic of China: lessons for the move towards universal health coverage. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217278. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217278

- Joint Annual Health Review 2016 [homepage on the internet]. Vietnam Ministry of Health. Available from: http://jahr.org.vn/downloads/JAHR2016/JAHR2016_Edraft.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Agustina R, Dartanto T, Sitompul R, et al. Universal health coverage in Indonesia: concept, progress, and challenges. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):75–102. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31647-7

- Singh PK, Travis P. Universal health coverage in the World Health Organization South-East Asia Region: how can we make it “business unusual”? WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2018;7:1–4. doi:10.4103/2224-3151.228420

- Tackling NCDs: best buys [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259232/WHO-NMH-NVI-17.9-eng.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- From Burden to “Best Buys”: reducing the Economic Impact of Non-Communicable Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Countries [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/nmh/publications/best_buys_summary.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, Bialous SA, Jackson RR. Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2015;385(9972):1029–1043. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60312-9

- Lebanon: needs assessment mission [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: http://www.who.int/fctc/implementation/needs/factsheet-na-fctc-lebanon.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Ambient air pollution [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/gho/phe/outdoor_air_pollution/en/. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Robertson L, Nyamurungi KN, Gravely S, et al. Implementation of 100% smoke-free law in Uganda: a qualitative study exploring civil society’s perspective. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5869-8.

- Workforce Resources for Health in Developing Countries [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/media/KeyMessages_3GF.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2019.

- Bangdiwala SI, Fonn S, Okoye O, Tollman S. Workforce resources for health in developing countries. Public Health Rev. 2010;32(1):296–318. doi:10.1007/BF03391604

- Lim LL, Lau ES, Kong AP, et al. Aspects of multicomponent integrated care promote sustained improvement in surrogate clinical outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(6):1312–1320. doi:10.2337/dc17-2010

- Lemaire JB, Wallace JE. Burnout among doctors. BMJ. 2017;358:j3360. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3360

- Long H, Huang W, Zheng P, et al. Barriers and facilitators of engaging community health workers in non-communicable disease (NCD) prevention and control in China: a systematic review (2006–2016). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2378. doi:10.3390/ijerph15112378

- CSEM reflections on UHC global monitoring report [homepage on the internet]. Available from: https://www.uhc2030.org/fileadmin/uploads/uhc2030/Documents/Key_Issues/UHC2030_civil_society_engagement/CSEM_GMR_Commentary_2019_EN_WEB.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Expert group meeting on the science‐policy interface summary [homepage on the internet]. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2075Summary%20of%20science-policy%20interface%20EGM_final.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- Approaches to establishing country-level multisectoral coordination mechanisms for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/entity/noncommunicable_diseases/documents/ncd-multisectoral-coordination.pdf?ua=1. Accessed October 30, 2019.

- Heymann DL, Chen L, Takemi K, et al. Global health security: the wider lessons from the west African Ebola virus disease epidemic. Lancet. 2015;385(9980):1884–1901. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60858-3

- Zhang Y, Xu J, Li H, Cao B. A novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a call for action. Chest. 2020;157(4):e99–e101. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2020.02.014

- Walls H, Smith R, Cuevas S, Hanefeld J. International trade and investment: still the foundation for tackling nutrition related non-communicable diseases in the era of Trump? BMJ. 2019;365:I2217. doi:10.1136/bmj.l2217

- CDC’s Vision for Public Health Surveillance in the 21st Century [homepage on the internet]. Centers for Disease Control. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6103.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2019.

- Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study [homepage on the internet]. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Available from: http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/2019/GBD_2017_Booklet.pdf. Accessed October. 30, 2019.

- IDF Diabetes Atlas 9th edition 2019 [homepage on the internet]. International Diabetes Federation. Available from: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Kroll M, Phalkey RK, Kraas F. Challenges to the surveillance of non-communicable diseases – a review of selected approaches. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2570-z

- Sharma A. Global research priorities for noncommunicable diseases prevention, management, and control. Int J Non-Commun Dis. 2017;2:107–112.

- Chia YC, Gray SY, Ching SM, Lim HM, Chinna K. Validation of the Framingham general cardiovascular risk score in a multiethnic Asian population: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e007324. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007324

- WHO/ISH Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Charts Strengths and Limitations [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/cvd_qa.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- STEPS: A framework for surveillance [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/ncd_surveillance/en/steps_framework_dec03.pdf. Accessed October 25, 2019.

- Ramos-Cañizares IJ. E-Sakto: lowering the cardiovascular risk of patients with hypertension and diabetes through public–private partnership. KnE Social Sci. 2018;3(6):578. doi:10.18502/kss.v3i6.2406

- Joshi R, Alim M, Kengne AP, et al. Task shifting for non-communicable disease management in low and middle income countries – a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103754. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103754

- Fisher EB, Coufal MM, Parada H, et al. Peer support in health care and prevention: cultural, organizational, and dissemination issues. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2014;35. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182450

- Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(11):11. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3

- Beating non-communicable diseases in the community: the contribution of pharmacists [homepage on the internet]. International Pharmaceutical Federation. Available from: https://www.fip.org/files/content/publications/2019/beating-ncds-in-the-community-the-contribution-of-pharmacists.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2019.

- Bizri LE The role of the community pharmacists in non-communicable diseases: it is time for change. Proceedings of the 26th Annual Congress of Lebanese Order of Pharmacists; November 16–18, 2018; Beirut, Lebanon.

- Primary Health Care Systems (PRIMASYS): comprehensive case study from Lebanon [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/projects/AHPSR-PRIMASYS-Lebanon-comprehensive.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Tuangratananon T, Wangmo S, Widanapathirana N, et al. Implementation of national action plans on noncommunicable diseases, Bhutan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;97(2):129–141. doi:10.2471/BLT.18.220483

- Marsiglia FF, Booth JM. Cultural adaptation of interventions in real practice settings. Res Soc Work Pract. 2015;25(4):423–432. doi:10.1177/1049731514535989

- Global Tobacco Economics Consortium. The health, poverty, and financial consequences of a cigarette price increase among 500 million male smokers in 13 middle income countries: compartmental model study. BMJ. 2018;361:k1162. doi:10.1136/bmj.k1162

- Malta DC, Oliveira TP, Luz M, Stopa SR, da Silva Junior JB, Dos Reis AA. Smoking trend indicators in Brazilian capitals, 2006–2013. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20(3):631–640. doi:10.1590/1413-81232015203.15232014

- Portes LH, Machado CV, Turci SR, Figueiredo VC, Cavalcante TM, Silva VL. Tobacco Control Policies in Brazil: a 30-year assessment. Cien Saude Colet. 2018;23:1837–1848. doi:10.1590/1413-81232018236.05202018

- “Sin Tax” expands health coverage in the Philippines [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/features/2015/ncd-philippines/en/. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- Follow-up to the high-level meetings of the United Nations General Assembly on health-related issues [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327434. Accessed October 29, 2019.

- Tools for implementing WHO PEN [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: who.int/ncds/management/pen_tools/en/. Accessed October 27, 2019.

- Chang AY, Cowling K, Micah AE, et al. Past, present, and future of global health financing: a review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 195 countries, 1995–2050. Lancet. 2019;393(10187):2233–2260. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30841-4

- Piot P, Caldwell A, Lamptey P, et al. Addressing the growing burden of non–communicable disease by leveraging lessons from infectious disease management. J Glob Health. 2016;6(1).

- Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare. Healthc Manage Forum. 2017;30(2):111–116. doi:10.1177/0840470416679413

- Quinn CC, Swasey KK, Crabbe JCF, et al. The impact of a mobile diabetes health intervention on diabetes distress and depression among adults: secondary analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2017;5(12):e183. doi:10.2196/mhealth.8910

- Murthy N, Chandrasekharan S, Prakash MP, et al. The Impact of an mHealth voice message service (mMitra) on infant care knowledge, and practices among low-income women in india: findings from a pseudo-randomized controlled trial. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23(12):1658–1669. doi:10.1007/s10995-019-02805-5

- Yang Q, Van Stee SK. The comparative effectiveness of mobile phone interventions in improving health outcomes: meta-analytic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;7(4):e11244. doi:10.2196/11244

- Dobe M. Health promotion for prevention and control of non-communicable diseases: unfinished agenda. Indian J Public Health. 2012;56(3):180. doi:10.4103/0019-557X.104199

- Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7182):527–530. doi:10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527

- Maneze D, Weaver R, Kovai V, et al. “Some say no, some say yes”: receiving inconsistent or insufficient information from healthcare professionals and consequences for diabetes self-management: A qualitative study in patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;156(107830):107830. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107830

- Vahdat S, Hamzehgardeshi L, Hessam S, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Patient involvement in health care decision making: a review. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(1). doi:10.5812/ircmj.12454

- Setia S, Ryan N, Nair PS, Ching E, Subramaniam K. Evolving role of pharmaceutical physicians in medical evidence and education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:777–790. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S175683

- Setia S, Tay JC, Chia YC, Subramaniam K. Massive open online courses (MOOCs) for continuing medical education – why and how? Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:805–812. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S219104

- De Martino I, D’Apolito R, McLawhorn AS, Fehring KA, Sculco PK, Gasparini G. Social media for patients: benefits and drawbacks. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10(1):141–145. doi:10.1007/s12178-017-9394-7

- Islam SM, Tabassum R, Liu Y, et al. The role of social media in preventing and managing non-communicable diseases in low-and-middle income countries: hope or hype? Health Policy Technol. 2019;8(1):96–101. doi:10.1016/j.hlpt.2019.01.001

- Kakkar AK, Sarma P, Medhi B. mHealth technologies in clinical trials: opportunities and challenges. Indian J Pharmacol. 2018;50(3):105–107. doi:10.4103/ijp.IJP_391_18

- Ristau RA, Yang J, White JR. Evaluation and evolution of diabetes mobile applications: key factors for health care professionals seeking to guide patients. Diabetes Spectr. 2013;26(4):211–215. doi:10.2337/diaspect.26.4.211

- mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organisation. Available from: https://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_mhealth_web.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- Joshi A, Rane M, Roy D, et al. Supporting treatment of people living with HIV/AIDS in resource limited settings with IVRs. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; April 2014; Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Mohiuddin AK. Diabetes fact: Bangladesh perspective. Int J Diabetes Res. 2019;2(1):14–20.

- Huckvale K, Wang CJ, Majeed A, Car J. Digital health at fifteen: more human (more needed). BMC Med. 2019;17(1):1–4. doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1302-0

- Beran D, Pedersen HB, Robertson J. Noncommunicable diseases, access to essential medicines and universal health coverage. Glob Health Action. 2019;12(1):1670014. doi:10.1080/16549716.2019.1670014

- Briggs AM, Persaud JG, Deverell ML, et al. Integrated prevention and management of non-communicable diseases, including musculoskeletal health: a systematic policy analysis among OECD countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(5):e001806. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001806

- Mishra SR, Sharma A, Kaplan WA, Adhikari B, Neupane D. Liberating data to combat NCDs. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(6):482–483. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30054-7

- Roshandel G, Khoshnia M, Poustchi H, et al. Effectiveness of polypill for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases: a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:672–683. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31791-X

- Prevalence of tobacco smoking [homepage on the internet]. World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/gho/tobacco/use/en/. Accessed February 17, 2020.

- Escobar ER, Gamino MN, Salazar RM, et al. National trends in alcohol consumption in Mexico: results of the National Survey on Drug, Alcohol and Tobacco Consumption 2016–2017. Salud Ment. 2018;41(1):7–16.

- Shamah-Levy T, Romero-Martínez M, Cuevas-Nasu L, Méndez Gómez-Humaran IM, Antonio Avila-Arcos M, Rivera-Dommarco JA. The Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey as a Basis for Public Policy Planning: overweight and Obesity. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1727. doi:10.3390/nu11081727