Abstract

Purpose

Asthma is a common chronic disease with gender differences in terms of severity and quality of life. This study aimed to understand the gendered practices of male asthmatic adolescents in terms of living with and managing their chronic disease. The study applied a sociological perspective to identify the gender-related practices of participants and their possible consequences for health and disease.

Patients and methods

The study used a combined ethnomethodology and grounded theory design, which was interpreted using Bourdieu’s theory of practice. We aimed to discover how participants interpreted their social worlds to create a sense of meaning in their everyday lives. The study was based on multistage focus group interviews with five adolescent participants at a specialist center for asthmatic children and youths. We took necessary precautions to protect the participants, according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the hospital’s research department.

Results

The core concept for asthmatic male adolescents was being men. They were focused on being nonasthmatic, and exhibited ambivalence towards the principles of the health services. Physical activity supported their aim of being men and being nonasthmatic, as well as supported their treatment goals. Being fearless, unconcerned, “cool,” and dependent also supported the aim of being men and being nonasthmatic, but not the health service principle of regular medication. Occasionally, the participants were asthmatic when they were not able to or gained no advantages from being nonasthmatic. Their practice of being men independently of being asthmatic emphasized their deeply gendered habits.

Conclusion

Understanding gender differences in living with and managing asthma is important for health workers. Knowledge of embodied gendered habits and their reproduction in social interactions and clinical work should be exploited as a resource during the supervision of asthmatic adolescent boys.

Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic disease. About 10% of the adolescent population in Scandinavia has medically diagnosed asthma.Citation1,Citation2 Adolescent and postadolescent males have a higher health-related quality of life than females,Citation3–Citation6 but there is a gender difference in how adolescents manage and live with chronic disease.Citation7

“Doing gender” is a sociological term derived from the writings of West and Zimmerman. Citation8 The term has its roots in ethnomethodology, and refers to gendered practices as ongoing situated processes rather than a being.Citation8 In this study, the term is used in the context of Bourdieu’s theory of practice.Citation9

The aim of this study was to explore gendered practices among adolescent boys who were living with and managing asthma. We investigated different practices and embodied habits, and found a sense of ambivalence about health when “doing gender.” The conclusion summarizes the study’s findings and their implications for health personnel practice.

Background

Bourdieu’s theory of practiceCitation9 describes the deeply embodied habits and practices of people as an ongoing process. The pattern of deep habits in different social groups is described as structured, while the same habits simultaneously recreate the pattern. Statistical patterns do not indicate social laws, but they occur because practices tend to constantly reproduce themselves. The reproduction of embodied habits is based on habitus, which is a set of capital disposals. Bourdieu widened the term “capital” from an economic context to incorporate cultural, symbolic, and social capital. Here, the concept of capital is briefly explained in the theoretical background, but it is not explained further in this study. Capital is realized through embodied habits, which mediate the self and social interactions.Citation9 The social field is the context of the social interactions that we naturally delimit and examine.Citation10 Gendered practice refers to the pattern of embodied habits in groups of men or women in social fields.Citation11 West and Zimmerman’s concept of “doing gender”Citation8 is a supplementary theoretical perspective in gendered practice. The concept describes gender as contextual and situated, and as a process. Both theories focus on what people do and construct, rather than categorizing them using fixed terms.

WilliamsCitation7 described how adolescent boys with asthma and diabetes did gender and addressed their health by excluding their chronic diseases from their personal and social sphere. At the same time, most of these boys made choices about their activities and diets that improved their health. HanssonCitation12 reported that young men often camouflage their disease from both themselves and their surroundings. He also reported that there was a mismatch between the biomedical intentions of health workers and the actual experiences of patients. Thus, their disease and body were objects of a biomedical agenda when they received medical information and treatment. At the same time, the biomedical agenda assumed that patients considered themselves to be self-consistent subjects, who took responsibility for their own health. HanssonCitation12 suggested that this was an explanation for the well-known noncompliance with medications among young asthmatic men.

In a study of gendered health, Lilleaas highlighted the vulnerability of the stronger sex,Citation13 as well as the need to understand the living and gendered body in health research and medicine.Citation14 Men tend to see their bodies as machines and as objects that can be used until they cease to function. They do not always care enough for their health and body when fulfilling their breadwinner role.Citation13 CharmazCitation15 studied the identity dilemmas of chronically ill men and described how the disease threatened their male identity. Consequently, males struggled to maintain their strength and continue as a breadwinner in their public sphere, whereas they often managed to assimilate their new situation as a chronically ill person into their private sphere.

There are different explanations for the well-documented gender difference in the quality of life among asthmatics.Citation3–Citation6 After adolescence, asthma is more severe for girls than for boys, which is related to the impact of hormonal changes.Citation16 This pattern of a decreased quality of life for girls compared with boys is also documented for other chronic diseases, and may be related to socioeconomic factors or other indicators of poor health, such as a high body mass index or smoking.Citation6 Osborne et alCitation3 suggest that there is a gendered response to asthma, which affects quality of life. Clark et alCitation17 suggest that gendered counseling can enhance self-regulation and quality of life, because it addresses gender-related factors such as hormonal changes and social factors that affect women with asthma. Understanding how adolescent boys do gender and how this affects their disease and health are important for the health staff working with these patients.

Material and methods

Research design

The study used a combined qualitative design. This was an ethnomethodological study which aimed to discover how participants interpreted their social worlds in a socially acceptable way and made sense of their everyday lives.Citation18 The meaning of words is indexical and context-dependent, so a qualitative interview can be considered as reflexive and a construction of meaning and knowledge based on how informants and the researcher bring themselves to each new situation.Citation19 The method clarified how the researcher and participants presupposed the construction of meaning during the interview situation and subsequent analysis.Citation19 The analysis employed the grounded theory approach proposed by Strauss and Corbin.Citation20 Grounded theory aims to discover the main concerns of the participants, and to explore how basic social processes explain the resolution of those concerns.Citation18 This method contributes the concepts of preopenness and systematic inductive analysis. Citation20 Both designs have their roots in symbolic interaction, which regard social interactions as consisting of meaningful communicative activity between individuals. Symbolic interaction focuses on the meaning of events to people and the symbols (ie, language) they use to convey that meaning.Citation18,Citation19

Ethnomethodology and the theory of practice treat habits as contextual; however, BourdieuCitation9 supplemented the understanding of habits by stating that they are bodily inscribed. Studies using this theoretical combination can help to understand the construction of a sense of meaning by participants and their preconscious embodied habits.

Setting and participants

This study was conducted in a specialist center for asthmatic children and youths in Norway during autumn 2010. This institution was focused on patients’ daily physical activity and their regular use of medication, which are also the two main issues in the treatment and self-regulation of asthma.Citation12 The inclusion criteria for the participants were: (1) males aged 13–16 years; (2) medically diagnosed asthma for ≥1 year; (3) sustained inhalation therapy for ≥1 year; and (4) agreement from the participant to be included in the study with permission from one of their parents.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted as semi-structured focus group interviews, which were audiotaped. A male nurse from the institution was present as an observer during the interviews. All participants were informed that the interviewer had been practicing as a children’s nurse for several years.

Focus group interviews are a well-documented means of promoting openness among the participants, where they can express their thoughts and follow the direction of further reflections to explore different perspectives.Citation21–Citation24 Each participant was interviewed twice to allow for further reflections on the same theme. HummelvollCitation25 described this method as a multistage focus group interview, which can allow more in-depth exploration of the same theme compared with single focus group interviews. The first interview (43 minutes) focused on how the participants lived and coped with their disease at that time. The second interview (51 minutes) focused on their future expectations as 25-year-old men. Both interviews were conducted within 24 hours. The participants were asked to write a short note between the sessions about their life expectations when they reached 25 years of age. Only one subject wrote this note, but all subjects said they had considered the theme, which was the main objective of this exercise. During both interviews, the subjects were asked questions about how they lived and how they managed current issues, but their reflections about these areas were not solicited because this was a descriptive process.

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed together with the note written by the one participant. A grounded theory approach was employed, as described by Strauss and Corbin.Citation20 First, the text was read several times to gain an appreciation of the material’s main issues. Second, the text was condensed using a systematic coding process. During the process, notes or memos were made to keep track of the iterative process between the text and the categories described by different authors.Citation20,Citation26 A brief overview of the analysis was achieved during the first level of coding, also known as “in vivo coding,”Citation18 which included a section about taking medicines at school, referred to as “I take my medicines openly.” This section was compiled with similar sections and renamed as the category “my asthma is well-known in my surroundings,” which is described as a level two code in grounded theory.Citation18 Axial coding was used after identifying the context and dimensions of this category, which was then renamed and linked to other sections of the text and categories. Finally, the same section could be tracked as part of the category “being asthmatic,” which was identified as level three coding. All categories identified are relative to each other and cover the complete text.

Ethical considerations

The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the hospital’s research department approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants who enrolled in the study, as well as from one of each participant’s parents before inclusion in the study. The leader of the hospital department where the study was conducted distributed written information to the boys and their parents, and access to conduct the interviews was allowed after consent was granted. Each interview began by providing information about the study, so the boys could choose not to participate for no particular reason and with no negative consequences. The names of the participants were changed during the analysis and when presenting the findings.

Results

The sample

This study included five participants between the ages of 13 and 15 who were all diagnosed with asthma during early childhood. They were all participating in a 4-week education/training/treatment program to help improve their health and self-regulation of medications. All of the participants used inhalation medications for symptom management and disease control. They knew each other from the institution, where they had been residents for 3 weeks prior to the interviews. One of the participants did not attend the first interview, but all five participants were present at the second interview.

The practices of male adolescents with asthma

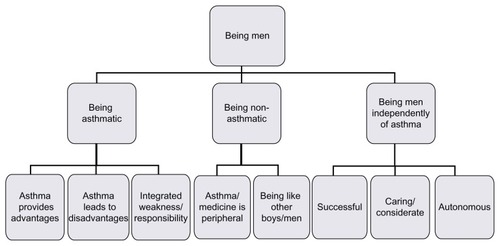

The core category identified in the material was “being men.” Linked to this were the main categories of “being asthmatic,” “being nonasthmatic,” and “being men independently of asthma.” A visual view of the main categories and their relationships is shown in .

Being asthmatic

“Being asthmatic” revealed how the boys saw themselves as asthmatics and how they used this to cope with themselves and others. All participants stated that they were open about their disease, and that all of their friends were aware of it. They did not mind taking their medicines in the locker room before taking part in physical education, and they suggested that their friends were sometimes jealous of the advantages they gained because of their asthma. Morgan stated that, “… I gave a lecture at school … and … they actually didn’t think about it. They think it’s cool actually [laughter] … they want to try as well …”

The participants were allowed an extra hour during school tests. They could easily drop out of swimming or physical education lessons and they could maintain their good marks even with bad performances if they informed their teachers that they were short of breath or had left their medications at home. The subcategory “asthma provides advantages” describes these issues.

As well as gaining advantages due to having asthma, the participants also described how “asthma leads to disadvantages.” The problems of taking longer in the morning and the bad mood of the teacher because they had to assimilate the asthmatic pupil were two examples of the disadvantages described. The physical weakness experienced occasionally by the participants, and their adaption to it were included in the subcategory of “integrated weakness/responsibility.” Integrated responsibility referred to the responses and actions required to cope with weakness. All subjects described their use of control medicine to prepare for episodes of shortage of breath, particularly taking their medicine before physical education and other activities.

Being nonasthmatic

In contrast to “being asthmatic,” the participants also described “being nonasthmatic.” They did not know the names of their medications, and medicines and asthma were described as being insignificant parts of their lives. Roy stated that, “I’m just normal like everybody else, I don’t have to speak about it you know.” When the researcher asked about what happened in a situation when Peter left his medicine at home during a weekend trip, he replied, “It went just fine.” During discussions about their future adult lives, they all stated that they hoped to grow out of their asthma, but the asthma would not make any difference if they did not. Karl said, “As far as I am concerned, I hope to get rid of it [the asthma], or that it improves, even if I don’t care about having asthma …” This relates to a subcategory of “being nonasthmatic” where “asthma/ medicine is peripheral.”

“Being dependent” is a subcategory of “asthma/medicine is peripheral.” Parents (mainly mothers) had the main responsibility for disease control. The parent and the doctor responded to the asthma, while the consultation at the doctor’s office was predictable and dealt only with medications and examinations. Again, Roy explained that, “… I always forget … just … which medicines … I don’t have a clue.” I asked about how they managed to remember their medicines during weekends, and Morgan answered, “Then, you have Mum.” This question was followed with, “But when you’re 25, you don’t have your mum?” and Morgan replied, “Then, you have a wife.”

“Physical activity” is another subcategory linked to “asthma/medicine is peripheral.” This category can be viewed as being the opposite of dependency, and is concerned with being strong, satisfied with physical achievements, and identifying with sporting models, which demonstrates ideals and actual physical activity. The two youngest subjects described an ideal that was linked to the institution’s treatment goal and sporting models in society, whereas one of the oldest subjects described a lot of actual physical activity.

“Being like other boys/men” is a second subcategory in “being nonasthmatic.” The two youngest subjects expressed “uncertainty” about how they handled their lives, while the two oldest subjects indicated what they felt was acceptable or unacceptable. They made fun of failures described by Peter and Karl, and they ridiculed the idea of placing a reminder note about medicines on the bathroom mirror. Robert occasionally disagreed when the two oldest seemed to agree, but he subsided after short disputes. Karl was the only boy who described an episode of severe shortage of breath using the phrase “asthma attack.” All of the other subjects denied experiencing these episodes, but they still discussed situations where they “breathed like a whale,” “became dizzy,” or were “breathless.” This phenomenon was categorized as “fearless/ unconcerned.” Roy in particular described the ideal of “being ‘cool.’” This subcategory was understood to mean not being too proper and not taking issues too seriously. “Uncertainty,” “fearless/unconcerned,” and “being cool” were all subcategories of “being like other boys/men.”

Being men independently of asthma

“Being men independently of asthma” reflected how boys were being men without linking it to their diagnoses, and this subcategory was linked to the core category of “being men.” The boys described a good man as being “successful” in terms of money and status. A good man was considered to be rich, and he had an important or heroic job, or great success in sports. At the same time, this status was linked to how “women define success.” Roy described his perfect day as an electrician:

… you are working with electricity in a house and a single lady is present … and then there is a lotto coupon, which she gives to you … and then … and then you complete the task (the electricity work) very fast, and your boss happens to notice this, and you become promoted, and known to the lady, then you win the lotto … excellent!

While relating this, his eyes and voice showed that the “single lady” was very attractive, so “known to the lady” was interpreted as becoming sweethearts. “Women defining success” was subordinate to “successful,” which in turn was subordinate to “being men independently of asthma.” All of the participants described a gorgeous girl admiring them for doing something extraordinary when they described their perfect day as adults.

A parallel category to “successful” was “autonomous.” Participants described a good life as freedom to do whatever they wanted (eg, travelling around the world without looking back). This phenomenon was superior to “being curious” and “sensation seeking.” Ultimately, they described a good man as being “caring and considerate.” They described how good men and fathers must care for their children and include them in healthy leisure pursuits.

Discussion

When interpreting the findings, it was necessary to consider the setting and situation where the data collection was conducted. At the institution, the staff repeatedly reiterated their focus on daily physical activity and how strictly they handled medication routines. After ending the first interview, the observer stated to one of the participants that a period of noncompliance with his medication routine must not recur. The institution’s routine and culture was related to strict medication routines and daily physical activity, which agreed with the modern asthma treatment described by Hansson.Citation12

Ethnomethodological interviews are a construction of meaning, which is essentially indexical, and a product of a person’s reflexivity.Citation19 The participants had all lived for years as asthma patients who engaged with the health services. The stories of their lives mirrored their adaptation to this context; this was how they handled their everyday lives to create meaning and sense. Their presence in the interview situation created a sense of meaning in the situation. The participants adapted to each other, the interviewer, and the observer – who were also nurses and men in this situation – while we adapted to the statements of the participants. From this perspective, each clinical consultation with patients creates a sense of meaning.

Bourdieu repeatedly emphasized reflexivity.Citation10 The researcher’s doxa, or unconscious assumptions, are present through habitus, practices, meaning, and sense throughout the entire research process. As a male nurse, the interviewer has adjusted to biomedical intentions and nursing practice in many ways. Thus, his practices and habits may have affected the discussions with the participants. By sensing a willingness to help, the participants may have related stories that they felt satisfied the interviewer’s intentions. Reflecting on these issues rather than denying them as nonexistent is the premise for all research, according to Bourdieu.Citation10 For example, the participants’ stories were partly about being dependent on their parents. This accorded with the researchers’ preconceptions, and the interviewer asked questions about this because he considered this to be an interesting phenomenon that conflicted with the goal of self-regulation. The interviewer’s questions about what they did and how they lived intentionally avoided reflection and encouraged them to talk about their practices; however, this still reflected unconscious values. Reflexivity is not about being neutral, but instead it is about revealing the researchers’ own practices and those of the participants. The present individuals and their practices are continuously influenced, and the participants influence each other during the interview process.Citation10

According to Bourdieu,Citation9 the habits and everyday philosophy that participants reveal can be conscious and unconscious. Their statements and actions are based on doxa. Laughing about placing a reminder note on the bathroom mirror about taking one’s medications may reveal an obvious, unquestioned way of living; they simply did not want to acknowledge this situation publicly. The participants described themselves in terms of ideals of autonomy, but they did not take into account their dependency on their parents when it came to the self-regulation of medication administration.

Living as an adolescent boy is part of the context for the participants. Their statements may be considered to be symbolic interactions (ie, how they present themselves to the researcher, the observer, and each other). They manage the current social processes and create social order.Citation19,Citation20 Their statements may also be considered as embodied habits,Citation9 whereas their actions and thoughts are incorporated in their existence, and simultaneously both post and pre to the social interaction they appear in.

BourdieuCitation9 described how practice and deep habits are structured, and how these habits also structure practice. For example, being cool or physically active can be viewed as adapting to ideals that are acceptable for a boy or a man. However, being cool or physically active can also be viewed as creating a boy or a man, and an unconscious creation of their everyday philosophy and embodied habits.

In the analysis, the daily physical activity and lack of a routine for self-medication were highlighted as practices of being nonasthmatic. Physical activity is a component of asthma treatment, but it is also synonymous with growing out of asthma and making it peripheral, according to the perceptions of the boys. Physical activity improves the self-reported health of adolescents in general,Citation27 but physical activity was not viewed as a method of managing asthma by the participants. Physical activity was merely a practice that made asthma as insignificant as possible. This agrees with Lilleaas’Citation13 concept of male practices, whereby they consider the body to be an object and a machine. WilliamsCitation7 also observed that male adolescents with asthma endanger their health, for example, by not taking precautions in case of shortness of breath related to physical activity, and not using their medicines as directed by health workers.

The participants’ lack of self-medication routines did not satisfy the treatment goals in the same way as physical activity. In terms of medication routines, the subjects were dependent, “cool,” fearless, and unconcerned. Medications and asthma were peripheral to their practice of being men and being nonasthmatic.

It may be assumed that asthmatic adolescents manage their life and disease based on complex unconscious competitive factors. Charmaz’sCitation15 focus on identity dilemmas can be used as a parallel, even if the focus of identity differs from the actual practice. Acceptance of and adapting to chronic illness in the privacy of family life may conflict with the lack of adaption in the public sphere.Citation15 The participants in this study were occasionally asthmatic, but this practice was subordinate to being men. Based on the current findings, it can be suggested that the practice of being nonasthmatic may conflict with being asthmatic in different situations. The practice revealed in the categories of “asthma provides advantages” and “integrated weakness/responsibility” can be considered to be a form of acceptance. Being “cool” and making asthma a peripheral element of someone’s life may be the opposite of acceptance. Thus, the dilemma between practices of acceptance and adjustment may be interpreted as competitive, which reveals further complexity.

The practices of being asthmatic and being nonasthmatic can be viewed as harmonizing the core concept of being men. The advantages linked to being asthmatic may be related to a need for hiding weakness and for being “cool,” fearless, and unconcerned. Hiding weakness may be a way of making sense to create meaning and acceptance as a boy or a man, although it can be viewed as a deep habit based on the doxa that men are not weak. This also suggests that while being asthmatic and open about the disease, they simultaneously hide their weakness by being nonasthmatic. Hansson’sCitation12 perspective of camouflaging asthma supports this suggestion. Moreover, being a cunning person in the eyes of their friends fits well with not being “cool” and too proper. In the context of their teachers and parents, these boys can easily slip away from their responsibilities and gain advantages by being asthmatic; given these advantages, they may appear nonasthmatic in the eyes of their friends. This makes sense when viewed from the perspective of symbolic interaction,Citation18,Citation19 and the social processCitation20 is resolved. A doxa of nonweakness and habits that embody these beliefs also fits well from the perspective of the theory of practice.Citation9

The core concept of these findings is being men. When interpreted using the theory of practice,Citation9 it is the most obvious way of living. The boys’ thoughts and embodied habits are based on their doxa of what a boy or man is or should be, which allows them to prioritize without considering the advice of health personnel. The strategy and practice of being asthmatic is dominant if participants can gain advantages, or when they are not able to hide or camouflage their disease. They may then accept and develop practices that health personnel could characterize as healthy and desirable. However, this study was conducted with only five participants, and all suggestions should be interpreted carefully.

Being men independently of asthma may not be an obvious practice that affects health and disease; however, it is a subcategory of being men. Autonomy, curiosity, care, and consideration could all harmonize with the health service agenda, and with adolescent boys being men and being asthmatic. These practices may act as resources for further reflective communication when supervising this patient group. Linking the intended practice of self-regulation and healthy physical activity with patients by discussing these embodied habits and reflected values may facilitate acceptable changes.

The ideal that success is defined by a woman is worth consideration. Being men is linked with having a lady who recognizes success. The boys also described the practices and ideals of being dependent on a woman, so they could maintain the practice of being “cool.” This perspective fits with Bourdieu’sCitation11 suggestion that Western culture views men and women as complementary opposites, although he has been criticized for generalizing his findings from the Kabyle society.Citation28 In other words, we can make a suggestion about how men are dependent on women to be complete men, while women are dependent on men to be complete women. Having a woman who recognizes success defines the good asthmatic man, while the same woman keeps the man healthy by supplying him with his required medication.

Being like other boys or men emphasizes the deep habits of asthmatic adolescent boys and the sense of meaning that they create. The need to adapt to what the group deems acceptable was obvious in the uncertainty of the two youngest subjects, according to the two oldest subjects. One of the participants subsided after several short disputes, which indicated his adaptation to the general culture of the group, to the acceptable practices of men, and was reflective of the embodied habits of being men.

Limitations of the study

This study was conducted with a limited number of participants, so the findings are not readily generalizable to large asthmatic male adolescent populations. However, for small group contexts with fewer participants, the findings provide an opportunity to gain an in-depth understanding of the cultural structures that are both reflected in and underlie the deep habits and practices of asthmatic male adolescents. From this perspective, this study provides insight into the ways in which individual habits differ, but also into the ways in which individual or small group habits follow cultural paths, or are set within existing cultural structures. SmithCitation29 argues that knowledge in postmodernism and poststructuralist research can be described with the metaphor “map,” not to “displace and subordinate people’s experience but can be used by them to expand their knowledge beyond it.”Citation29 Findings from the current study reflect an understanding of these cultural structures, and fit with findings in previous studies on men’s health.Citation13,Citation30 Future process studies within this research area can help to both deepen and widen the knowledge that has been developed in this paper.

The stories told by the participants may have influenced each other, which may have biased the current findings to the views of the most dominant member of the group.Citation22–Citation24 This issue was considered during the preparation of the study, as well as during the interviews and the analysis. Ahead of the interviews, information was gained about the participants from the staff of the institution, so they could be placed intentionally and appropriately around a table using name boards. HalkierCitation22 explains how the interviewer can then use eye contact, address a participant using his or her name to ask questions directly to the participants who are less engaged, and even having the interviewer turn his or her face away from the most dominant member to avoid having only one or two voices being heard. Using these techniques, the interviews conducted actually reflect the opinions and stories from all five participants; however, in a situation where participants in a group create meaning and sense,Citation19 a kind of “bias” created through domination and social order is inevitable, and it is even sometimes wanted in order to accurately reflect participants’ lives and social interactions. This issue is considered through the analysis. Future studies with additional participants may both confirm and vary findings from the current pilot study.

The findings from the present study may be transferable to clinical work to aid in the understanding of asthmatic adolescents. Citation31,Citation32 The participants represented a clinical patient group with knowledge of and experience with asthma, so they can be considered key informants,Citation18 or information rich.Citation33 This study was also conducted according to an approved qualitative research design,Citation18–Citation20 which was described openly with a clear theoretical framework.Citation9,Citation32 The findings were also interpreted and validated in light of previous research from different scientific traditions. The data and the analysis captured the intended focus of the study, which was a major issue for its credibility.Citation31 As with other qualitative studies, the findings were influenced by the researcher’s preconceptions.Citation34 It was also implicit in the research design of the study and its theoretical framework that the interviewer was doing gender while conducting interviews. With the aim of emphasizing reflexivity, a professor and a group of experienced qualitative researchers supervised the research process. Reflections and discussions about norms, practices, values, and intended changes were maintained throughout the overall process. This increased the conformability and the trustworthiness/dependability of the study,Citation33,Citation31 as did the feedback from the observer who, together with the research group, can be considered as different “legitimate knowers,” as described by Kvale and Brinkmann,Citation21 as well as by Hesse- Biber and Leavy.Citation26

Conclusion

This study revealed embodied habits and practices that both conflicted and were aligned with medical advice for the patient group. In conclusion, we can state that gendered practices were deeply incorporated within the bodies, lives, and diseases of the participants. Knowledge and understanding of this concept is essential for health workers.

This study makes no conclusion about how we can consciously change embodied habits and develop new practices among health personnel or patients. However, BourdieuCitation11 claimed that it is necessary to identify deep unconscious habits and doxa. In clinical care, the unconscious deep habits that are identified may reflect the appropriateness to create a sense of meaning that also improves one’s health. However, Bourdieu also claimed that even if practices change, certain embodied habits, socialization conditions, and cultural influences are deeply incorporated and resistant to change.Citation11

The ambivalence observed in this study can be exploited as a resource when supervising asthmatic adolescent boys. If similar deep habits and doxas of boys are identified in clinical situations, one can assume that these habits may be threatened by the efforts of health workers to strictly enforce patients’ medication routines. The boys’ need to be strong and physically active may be threatened by highlighting their weaknesses; this could also explain the risk-taking behavior described in previous studies.Citation7

Future research should focus on developing clinical care practices for asthmatic adolescent boys, and evaluate whether or not this patient group may receive better health services if gendered perspectives are implemented in routine clinical practice. Health researchers may develop a research-based tool to support this integration, and evaluate the consequences of health personnel making efforts to accept the boys’ deeply engrained habits, helping them to identify what they take for granted, while exploring acceptable steps in order to make changes, and exploiting the ambivalent priorities of asthmatic adolescent boys. Reflexivity and knowledge about what health personnel take for granted when consulting patients should also be emphasized and evaluated in future research, since that reflects how they, together with patients, create a sense of meaning in clinical situations.Citation19

Further research should also focus on how asthmatic adolescent girls do gender to obtain an understanding of how they live with and manage their asthma.

Acknowledgments

Thomas Westergren was supervised by Ulla-Britt Lilleaas, and he was responsible for the study’s conception and design, and for drafting the manuscript. He also performed the data collection and analysis, and Ulla-Britt Lilleaas made critical revisions to the analysis and the paper.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WennergrenGEkerljungLAlmBErikssonJLötvallJLundbäckBAsthma in late adolescence – farm childhood is protective and the prevalence increase has levelled offPediatr Allergy Immunol201021580681320408968

- HenriksenAHHolmenTLBjermerLGender differences in asthma prevalence may depend on how asthma is definedRespir Med200397549149712735665

- OsborneMLVollmerWMLintonKLBuistASCharacteristics of patients with asthma within a large HMO: a comparison by age and genderAm J Respir Crit Care Med199815711231289445289

- BurkhartPVSvavarsdottirEKRayensMKOakleyMGOrlygsdottirBAdolescents with asthma: predictors of quality of lifeJ Adv Nurs200965486086619243461

- RydströmIDalheim-EnglundACHolritz-RasmussenBMöllerCSandmanPOAsthma – quality of life for Swedish childrenJ Clin Nurs200514673974915946282

- NalewayALVollmerWMFrazierEAO’ConnorEMagidDJGender differences in asthma management and quality of lifeJ Asthma200643754955216939997

- WilliamsCDoing health, doing gender: teenagers, diabetes and asthmaSoc Sci Med200050338739610626762

- WestCZimmermanDHAccounting for doing genderGender and Society2009231112122

- BourdieuPOutline of a Theory of PracticeCambridgeCambridge University Press1977

- BourdieuPWacquantLJDAn Invitation to Reflexive SociologyCambridgePolity Press1992

- BourdieuPMasculine DominationCambridgePolity Press2001

- HanssonKI Ett Andetag: En Kulturanalys av Astma som Begränsning och MöjlighetIn a Breath: A Cultural Analysis of Asthma as Limitation and PossibilityStockholmCritical Ethnography Press2007 Swedish

- LilleaasUBDet sterke kjønns sårbarhetThe vulnerability of the stronger sexSosiologisk Tidsskrift200614311325 Norwegian

- LilleaasUBDen sosiale kroppenThe social bodyTidsskrift for Sygeplejeforskning200831320 Norwegian

- CharmazKIdentity dilemmas of chronically ill menSociol Q1994352269288 Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4121547Accessed October 18, 2012

- AlmqvistCWormMLeynaertBfor working group of GA2LEN WP 2.5 GenderImpact of gender on asthma in childhood and adolescence: a GA2LEN reviewAllergy2008631475717822448

- ClarkNMGongZMWangSJValerioMABriaWFJohnsonTRFrom the female perspective: Long-term effects on quality of life of a program for women with asthmaGend Med20107212513620435275

- PolitDFBeckCTEssentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing PracticePhiladelphiaWolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins2010

- DowlingMEthnomethodology: time for a revisit? A discussion paperInt J Nurs Stud20074482683316824525

- StraussACorbinJBasics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and TechniquesNewbury Park (CA)Sage1990

- KvaleSBrinkmannSInterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research InterviewingLos Angeles (CA)Sage2009

- HalkierBFokusgrupperFocus GroupsFrederiksbergSamfundslitteratur2008 Danish

- MorganDLFocus Groups as Qualitative Research2nd edThousand Oaks (CA)Sage1997

- KruegerRACaseyMAFocus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research4th edLos Angeles (CA)Sage2009

- HummelvollJKMulti-stage focus group interview: a central method in participatory and action-oriented research designsKlin Sygepleje2010243413

- Hesse-BiberSNLeavyPThe Practice of Qualitative ResearchThousand Oaks (CA)Sage2006

- NesheimTHauglandSPhysical activity and perceived health among 11–15-year old NorwegiansTidsskr Nor Laegeforen2003123677277412693111

- FowlerBReading Peirre Bourdieu’s Masculine Domination: notes towards an intersectional analysis of gender, culture and classCultural Studies2003173/4468494

- SmithDETelling the truth after postmodernismSymbolic Interaction1996193171202

- LilleaasUBMasculinities, sport, and emotionsMen and Masculinities20071013953

- GraneheimUHLundmanBQualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthinessNurse Educ Today200424210511214769454

- MalterudKQualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelinesLancet2001358928048348811513933

- CheekJOnslowMCreamABeyond the divide: comparing and contrasting aspects of qualitative and quantitative research approachesInt J Speech Lang Pathol200463147152

- NyströmMDahlbergKPre-understanding and openness – a relationship without hope?Scand J Caring Sci200115433934612453176