Abstract

Chronic pain is largely underdiagnosed, often undertreated, and expected to increase as the American population ages. Many patients with chronic pain require long-term treatment with analgesic medications, and pain management may involve use of prescription opioids for patients whose pain is inadequately controlled through other therapies. Yet because of the potential for abuse and addiction, many clinicians hesitate to treat their patients with pain with potentially beneficial agents. Finding the right opioid for the right patient is the first – often complicated – step. Ensuring that patients continue to properly use the medication while achieving therapeutic analgesic effects is the long-term goal. Combined with careful patient selection and ongoing monitoring, new formulations using extended-release technologies incorporating tamper-resistant features may help combat the growing risk of abuse or misuse, which will hopefully reduce individual suffering and the societal burden of chronic pain. The objective of this manuscript is to provide an update on extended-release opioids and to provide clinicians with a greater understanding of which patients might benefit from these new opioid formulations and how to integrate the recommended monitoring for abuse potential into clinical practice.

Introduction

Chronic pain is a societal problem that is likely to become increasingly significant with the aging of the American population. The most recent estimate from the Institute of Medicine suggests that at least 100 million American adults have chronic pain: more than those affected by heart disease, cancer, and diabetes combined.Citation1 It is believed that 25% of American adults are affected by moderate to severe chronic pain, and 6%–13% of adults report severe disabling pain.Citation2,Citation3 The prevalence of chronic pain appears to be higher among women than men,Citation2,Citation3 and seems to increase with age.Citation2–Citation4 Chronic pain interferes with quality of life (QoL) and sleep; it leads to diminished cognitive function, impaired relationships, decreased productivity, and increased mental health concerns, particularly anxiety and depression.Citation5–Citation7

Despite its high prevalence, chronic pain remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. More than half of patients with pain are managed by their primary care physician; only 2% are managed by a pain specialist.Citation3,Citation8 Paradoxically, while nearly half of all patients with chronic pain receive inadequate analgesia,Citation3,Citation7,Citation9,Citation10 the use of prescription opioids for pain management has escalated to approximately 20% of all prescriptions.Citation11 These findings suggest that some patients are receiving a disproportionately large amount of analgesics while others remain undertreated.

Most patients with chronic pain receive long-term treatment with analgesic medications. Opioids are suggested when other, less problematic approaches are ineffective or poorly tolerated, or if the benefit–risk of their use is surpassed by opioids.Citation12–Citation14 However, there are issues associated with long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain, particularly with respect to the risk of tolerance, dependence, or abuse.Citation15–Citation18 While it is broadly accepted that chronic opioid therapy is associated with the development of tolerance, the exact nature of this and the extent to which it may limit the clinical utility of opioid therapy are still poorly characterized.Citation19 Evidence of long-term improvements in functional activity is also inconclusive, and the continuing effectiveness of opioids taken chronically is difficult to quantify, as the quality of long-term efficacy studies varies widely.Citation16 However, despite these concerns, multiple expert panels have concluded that chronic opioid therapy can be effective for patients with chronic noncancer pain who are carefully selected and monitored.Citation17

The introduction of new extended-release (ER) formulations has provided physicians with a range of management options. More recently, a selection of putative abuse-deterrent formulations (ADFs) of these agents have also been employed. Early data suggest that these formulations may be impacting abuse specific to individual drugs, although no impact on community rates of abuse has so far been reported.Citation20 The objective of this review is to provide an update on ER opioids and to furnish clinicians with a greater understanding of which patients might benefit from these new opioid formulations and how recommended monitoring for abuse potential may be integrated into clinical practice.

Managing chronic pain with extended-release opioids

Several well-described reasons have been identified for limiting prescription of opioids for patients who might benefit from them. Clinicians are especially reluctant to prescribe opioid analgesics because of regulatory oversight concerns, documentation requirements, fear of abuse potential, and lack of foundational knowledge regarding these agents.Citation8,Citation21 Consequently, nearly one in three clinicians do not initiate opioid therapy.Citation22 Recent data suggest this fear or lack of understanding exists across various diseases and clinical environments. For example, a recent study showed that one-third of patients with invasive cancer pain had inadequate analgesic prescribing, and minorities were twice as likely not to receive adequate pain medication.Citation23 Furthermore, some patients may choose to live with some degree of chronic pain for various reasons (eg, to avoid common side effects of opioids or other analgesics).Citation24 Patient-centered care must therefore encourage greater understanding of the appropriate use of opioids, to enable more patients with chronic pain to receive analgesia that is adequate for their requirements and to experience improvements in work capacity, functioning, and QoL, while minimizing abuse potential.

Pharmacokinetics of extended-release formulations

Prescription opioids can be categorized according to several different parameters, including affinity and selectivity for opioid receptors, pharmacodynamic effects, and pharmacokinetic profiles. Most commercially available prescription opioids exert clinical effects via interactions with mu-opioid receptors and produce a constellation of typical opioid-mediated effects, including analgesia, sedation, nausea, constipation, and (potential) elevations in mood. Regarding their relative ability to produce such effects, opioid analgesics are categorized as either weak (eg, codeine, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, and tramadol) or strong (eg, oxycodone, hydromorphone, morphine, fentanyl, and oxymorphone).Citation25 Prescription opioids are available as immediate-release (IR) or ER formulations, distinguishing features that have relevance for their clinical utility. As with IR opioids, which typically have clinical effect for 3–6 hours, common side effects with ER formulations include constipation, nausea, and somnolence.Citation26–Citation31 In addition, respiratory depression and risk of death from overdose have been directly associated with higher opioid doses.Citation32

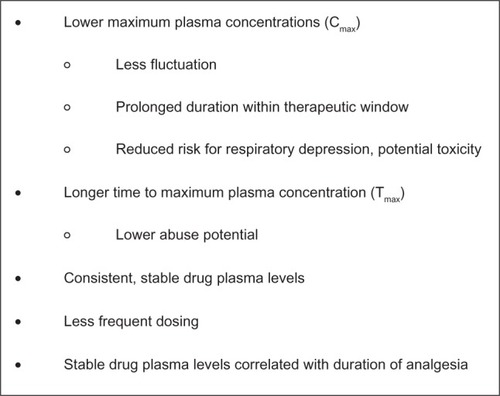

Compared with IR formulations, ER formulations are specifically designed to allow a controlled release of the active agent to provide relatively consistent and prolonged plasma drug levels with lower maximum concentration (Cmax) and fewer peak-to-trough fluctuations ().Citation26,Citation33 To prevent gaps in pain relief, IR formulations require regular administration every 4–6 hours, and consequently produce numerous peaks and troughs in plasma drug levels throughout the day. In contrast, ER formulations are dosed less frequently (one to three times per day or fewer), allowing for less fluctuation and affording an elongated duration within the therapeutic window.Citation34 In addition, a lower maximum daily dose has been associated with a reduced risk of respiratory depression and overdose.Citation32 The time to peak blood concentration level (Tmax) is generally longer with ER formulations, a parameter that may confer a reduced abuse liability when intact tablets are taken whole (see below).Citation35,Citation36 Two separate surveys, one sent to patients and the other to physicians, concluded that the two most important factors when selecting an opioid are the ability to relieve pain and the duration of pain relief.Citation37 Studies demonstrate that duration of stable blood plasma levels is significantly correlated with the overall duration of analgesia.Citation26,Citation34

Figure 1 Putative pharmacokinetic advantages of extended-release versus immediate-release opioids.Citation26,Citation33

ER opioids have been shown to be efficacious for treatment durations of up to 1 year in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain associated with a variety of underlying etiologies, including low-back pain,Citation38–Citation44 osteoarthritis,Citation40,Citation41,Citation45–Citation47 postherpetic neuralgia,Citation48 and neuropathic pain.Citation49,Citation50 Although prescriptions using IR preparations are far more prevalent than those using ER formulations,Citation51 few studies have directly compared ER with IR opioid formulations. At the time of this writing, there is no clear evidence to recommend one over the other.Citation30,Citation51,Citation52 Additional head-to-head studies are necessary to elucidate the range of conditions under which ER opioids perform better.

Extended-release opioid formulations

A number of oral and transdermal ER opioid formulations are currently available ().Citation53–Citation66 Clinically important differences focus on the pharmacokinetics of individual agents and the benefits related to specific formulations. Potency, defined as the dose required to produce a given effect, is typically compared relative to morphine and differs not only between agents but also by both route of administration and whether the formulation is IR or ER.Citation67 Recent additions to the pharmacologic armamentarium include formulations designed to reduce abuse liability among the subset of people who manipulate existing formulations to obtain a faster or greater opioid response; although these ADFs cannot reduce or eliminate all means for opioid abuse, they may help deter particular forms of opioid abuse among specific populations.

Table 1 Extended-release opioidsCitation53–Citation66

Morphine

Morphine is considered the prototype of pure mu-agonist opioids.Citation27 Oral controlled-, extended-, and sustained-release morphine formulations are available in the United States as tablets or capsules. Recent additions include a once-daily capsule formulation containing both IR and ER beads that release morphine in a distinct time-dependent manner using a spheroidal oral drug-absorption system, or SODAS (Avinza; King Pharmaceuticals, Bristol, TN, USA), and a once- or twice-daily ER capsule (Kadian; Actavis Elizabeth, Morristown, NJ, USA).Citation27,Citation54,Citation56,Citation68 The once-daily formulation provides the same total systemic exposure over 24 hours as the twice-daily formulation, but with different pharmacokinetics, including a lower Cmax and higher Cmin, resulting in reduced peak-to-trough fluctuations compared with the twice-daily formulation.Citation27,Citation68,Citation69 The controlled-release (MS Contin; Purdue Pharma, Stamford, CT, USA) and sustained-release formulations (Oramorph SR; Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals, Newport, KY, USA) are dosed every 12 hours but can be dosed every 8 hours for patients whose pain is not fully controlled over the 12-hour release time.Citation57,Citation58 An ADF that combines morphine sulfate with naltrexone hydrochloride has been developed, but is not currently being marketed (Embeda; King Pharmaceuticals).Citation55 For all available morphine formulations, studies suggest that food impacts the pharmacokinetics, predominantly by increasing Tmax, although some research suggests that food can also increase the area under the curve (AUC) and Cmax for IR and specific ER morphine formulations.Citation34

Oxymorphone

Oxymorphone is a semisynthetic opioid agonist with approximately two to three times greater analgesic potency and a more rapid onset of action compared with morphine.Citation70,Citation71 Originally, an ER matrix formulation using the TIMERx (Endo Pharmaceuticals, Chadds Ford, PA, USA) delivery system slowly releases oxymorphone over 12 hours to afford consistent plasma levels with low peak-to-trough fluctuations. Studies suggest a reasonable oral morphine: oxymorphone equianalgesic potency ratio of 2–3:1.Citation59,Citation67 A recently released putative ADF of oxymorphone ER (Opana ER; Endo Pharmaceuticals, Chadds Ford, PA, USA), in which the active drug is embedded in a hard polymer matrix (INTAC; Grünenthal, Aachen, Germany) is currently marketed in the United States.Citation59,Citation72 Clinical studies suggest these two oxymorphone ER formulations are bioequivalent and have similar safety profiles.Citation72 Modest alcohol consumption (modeled using 240 mL of 4% ethanol) along with oxymorphone ER tablets does not appear to have an effect, whereas moderate alcohol use or abuse (modeled using 240 mL of 20% and 40% ethanol, respectively) may produce meaningful consequences.Citation73 Coadministration of oxymorphone ER with 20% or 40% ethanol increased Cmax levels by an average of 31% and 70%, respectively, and the median Tmax was shortened by 30 minutes.Citation59,Citation73

Hydromorphone

A new once-daily, oral osmotic pump (OROS; Alza, Mountain View, CA, USA) formulation of the semisynthetic opioid hydromorphone (Exalgo, Mallinckrodt Brand Pharmaceuticals, Hazelwood, MO, USA) was approved in 2010 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).Citation60 This ADF provides relatively constant steady-state concentrations over 24 hours, equivalent AUCs, and a 26% lower Cmax and 43% higher Cmin compared with an IR hydromorphone formulation.Citation74,Citation75 Bioavailability is only minimally affected by food or alcohol.Citation76 This formulation has low plasma protein binding and low probability of interfering with the metabolism of other drugs.Citation76,Citation77 Research has demonstrated comparable steady-state plasma drug concentrations and bioequivalence between the OROS ER and IR formulations, with substantially smaller peak-to-trough fluctuations associated with OROS ER compared with IR hydromorphone formulations (61% vs 172%, respectively).Citation74 The hard exterior of the tablet has been shown to withstand significant force, minimizing its ability to be intentionally manipulated through biting or chewing.Citation78 In addition, after milling the tablet, only 30% of active ingredient could be recovered, minimizing the appeal of bolus doses through this form of manipulation.Citation78 When switching to OROS hydromorphone from morphine sulfate, the relative potency dose ratio is 5:1 (HM:MS).Citation75,Citation79

Tapentadol

Tapentadol has a dual mechanism of action: it is a mu-opioid receptor agonist and a norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitor, with minimal serotonin effects.Citation80,Citation81 As a mu-opioid, it has similar abuse liability to the other strong mu-opioids. The synergistic interaction may be particularly beneficial for patients with neuropathic pain,Citation80 and limited protein binding minimizes the risk of drug–drug interactions.Citation80 An oral ER formulation (Nucynta ER, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Titusville, NJ, USA) provides a 12-hour duration of effect with comparable analgesia and a favorable gastrointestinal tolerability profile.Citation61,Citation80,Citation82–Citation85 Tapentadol has recently had its indication expanded from chronic moderate to severe pain to include neuropathic pain resulting from diabetic peripheral neuropathy.Citation61

Oxycodone

Oxycodone controlled release (OxyContin; Purdue Pharma) is a pure mu-opioid receptor agonist that has an abuse potential similar to that of other strong opioids.Citation62 The controlled-release oxycodone formulation provides delivery of oxycodone continuously over a 12-hour period and has high oral bioavailability (60%–87%) due to low presystemic and/or first-pass metabolism.Citation62 Upon repeated dosing in healthy subjects in pharmacokinetic studies, steady-state plasma concentrations of oxycodone were achieved within 24–36 hours.Citation62

Methadone

Methadone (Dolophine, Roxane Laboratories, Columbus, OH, USA; Methadose, Mallinckrodt Brand Pharmaceuticals) is a highly lipophilic synthetic mu-opioid agonist with unique pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.Citation63,Citation64,Citation86 The relative potency may depend upon the dose of the opioid taken before the switch to methadone, and whether the patient was switching from or to methadone.Citation67 Unlike other ER opioids, methadone is an intrinsically long-acting opioid because it has a long and variable half-life, ranging from 12 to 120 hours, compared with 2–4 hours with oral morphine. This has been associated with an elevated risk of overdose deaths, because severe toxicities may not become apparent for 2–5 days.Citation33,Citation86 The low cost of methadone may account for the dramatic increases in prescriptions over the past decade.Citation22,Citation87 Although methadone represents fewer than 5% of opioid prescriptions dispensed, it is implicated in one in three opioid-related deaths.Citation87 Because of its unpredictable pharmacokinetics, caution should be used when prescribing methadone.Citation13

Transdermal formulations

In addition to the ER oral formulations, two transdermal formulations are available, one containing fentanyl and the other containing buprenorphine.Citation65,Citation66 Both fentanyl and buprenorphine are potent synthetic opioids that are highly lipophilic and have a low molecular weight.Citation88,Citation89 In addition to possible cutaneous reactions to the patches, patients should be aware that any direct heat to the attached patch – including increases in body temperature (eg, fevers) or elevations in ambient temperatures (eg, hot tubs, heating blankets) – can substantially increase the amount of active drug released.Citation88,Citation90

Fentanyl

The original transdermal fentanyl reservoir formulation has had problems with adhesion and is associated with a risk of drug leakage and greater ease of drug extraction, limiting its use.Citation91,Citation92 The newer matrix patch (Duragesic, Janssen Pharmaceuticals) was designed with a reduced drug load: drug-containing droplets are contained within a silicone matrix with a rate-controlling membrane.Citation65,Citation91,Citation92 The patch is to be replaced every 72 hours. Comparing reservoir to matrix systems indicates comparable systemic and topical safety profiles, as well as bioequivalent systemic exposures of fentanyl.Citation93 However, increased skin temperature, as through exposure to heat, has been associated with greater fentanyl absorption and may increase the risk of overdose.Citation94,Citation95 In addition, recent research indicates greater intrasubject and intersubject variability in absorption, metabolism due to genetic polymorphisms, and interference of metabolism associated with concomitant medication use than was previously observed, which has been associated with unpredictable adverse effects, including fatalities.Citation96 In general, the matrix patch appears to be less amenable to tampering than the traditional reservoir system: the design of the matrix patch makes it more difficult to extract active drug. Nevertheless, both types of patches contain very high doses of fentanyl both before and after use, increasing the risk for overdose.Citation94

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a semisynthetic derivative of thebaine, and its unique mechanism of action as a partial agonist at the mu-opioid receptor shows a decreased propensity to produce respiratory depression unless combined with other central nervous system (CNS) depressants.Citation89,Citation97 In contrast to the other mu-opioid receptor agonists that are Schedule II agents, buprenorphine is considered a Schedule III drug, meaning that it can be used for medical purposes and has a moderate (vs high) addiction potential. Therapeutic efficacy is achieved with daily doses of 0.5–2 mg, making it 25–50 times more potent as an analgesic per milligram than morphine.Citation89,Citation98 The low-dose transdermal 7-day buprenorphine matrix patch (Butrans, Purdue Pharma), recommended for patients with moderate to severe pain, appears to be efficacious, generally well tolerated, and convenient.Citation66,Citation99–Citation101 The formulation provides continuous delivery of buprenorphine to afford generally consistent plasma drug concentrations throughout the 7-day dosing interval.Citation97 It does not require dosage adjustments in older patients (aged ≥ 65 years) and has an adverse-event profile comparable to other opioid analgesics,Citation97 although local skin reactions can be therapy-resistant and may be treatment-limiting.Citation89 In an analysis of long-term use, data from a Norwegian Prescription Database study of 13,451 new users of this patch, from its introduction in November 2005 through December 2008, showed that nearly half (44%) of patients were dispensed only one prescription.Citation102

Therapeutic benefits of extended-release opioids

Among the putative benefits associated with the pharmacokinetic properties of ER formulations are the potential for sustained and consistent analgesia, less end-of-dose failure or breakthrough pain, and better consolidated nighttime pain control with less need for nighttime dosing.Citation5,Citation26,Citation27 Nearly 89% of patients with chronic pain report comorbid pain-related sleep disturbance; pain exacerbates sleep problems that can lead to physical and mental symptoms, including depression.Citation26,Citation103–Citation105 Although both IR and ER opioid formulations have the potential to improve sleep, IR agents may not provide as much benefit as ER formulations for patients who wake during the night with pain or who have early morning pain.Citation26 ER agents may facilitate more consolidated sleep patterns compared with IR agents.Citation106,Citation107 Sleep problems resulting from osteoarthritis-induced chronic pain were qualitatively and quantitatively improved after treatment with a once-daily ER morphine formulation.Citation108 Similarly, a higher percentage of patients with pain receiving a buprenorphine transdermal patch compared with patients receiving a placebo patch reported uninterrupted sleep for durations longer than 6 hours.Citation109

Both IR and ER formulations improve QoL measures of mood, social and overall physical function, and work.Citation26 However, ER formulations appear to improve treatment responses and afford better patient perceptions of QoL than do IR formulations.Citation107,Citation110 A recent study under real-world conditions involving once-daily ER morphine sulfate tablets demonstrated significantly reduced pain scores that led to improved sleep and physical functioning among patients with chronic moderate to severe pain over the 3-month study period.Citation65 Another study showed that a once-daily ER morphine sulfate formulation was associated with significantly better and earlier improvements in physical function and ability to work than a twice-daily oxycodone formulation.Citation111

Less frequent dosing may also facilitate greater treatment adherence.Citation5 ER formulations appear to increase adherence and reduce pain-related anxieties.Citation107 Good adherence has been associated with improved treatment efficacy in pain relief and QoL.Citation112

Clinical practices to promote appropriate choice and use of opioid formulations

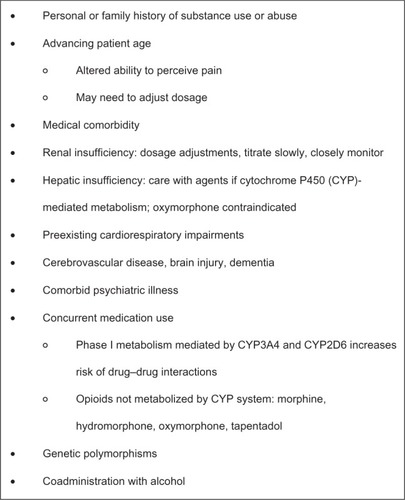

Whether prescribing ER or IR opioid therapy for an individual patient, selecting an appropriate formulation must take into consideration a variety of factors, including patient age, hepatic and renal status, the risk for drug–drug interactions, and the effects of coadministration with alcohol and other CNS depressants ().Citation12–Citation14

Figure 2 Factors to consider before initiating treatment with an opioid analgesic.Citation12–Citation14

Identifying appropriate candidates for extended-release opioid therapy

Opioids have demonstrated efficacy against most forms of pain.Citation13 However, prescription opioids are not appropriate for all patients and all chronic pain conditions. According to labeling by the FDA, modified-release opioids are “for the management of moderate to severe pain when a continuous, around-the-clock analgesic is needed for an extended period of time; they are not intended for intermittent dosing or as an as-needed analgesic.”Citation113 In addition, the boxed warning on all modified-release prescription opioids highlights the need for proper patient selection, noting that “persons at increased risk for opioid abuse include those with a personal or family history of substance abuse or mental illness. Patients should be assessed for their clinical risks for opioid abuse or addiction prior to being prescribed opioids. All patients receiving opioids should be routinely monitored for signs of misuse, abuse and addiction.”Citation113

Reviewing relevant patient health conditions

Health conditions such as hepatic or renal impairment and presence of cardiovascular disease, dementia, or cerebrovascular conditions can impact opioid effects, and patients should be assessed for these conditions prior to initiating opioids. Older patients, in particular, may be likely to have one or more of these comorbidities.Citation114 The slower metabolism of older patients, along with decreased renal and hepatic blood flow and mass, make them particularly vulnerable to adverse events and increased sensitivities to opioid agents.Citation14,Citation76,Citation115,Citation116 In addition, this population has a high use of polypharmacy, which may increase the likelihood of drug–drug interactions.Citation117 Similarly, older patients experience an elevated risk of respiratory depression, bradycardia, or hypotension with prescription opioid use.Citation114,Citation118,Citation119 Patients with existing cardiorespiratory impairment should be monitored very carefully if prescribed opioids.Citation52,Citation114,Citation120

Most opioid analgesics or their metabolites – active or inactive – are primarily eliminated in the urine, necessitating dosage adjustments for patients with significant renal impairments.Citation114 Clinicians can prescribe opioid analgesics – albeit with caution – to patients with renal or hepatic failure, using low doses and slow titration schedules.Citation114,Citation121,Citation122 Specific agents, including morphine, codeine, and hydromorphone, should be avoided or used with caution, because of the accumulation of bioactive drug or metabolites, which might result in potential toxicities.Citation59,Citation62,Citation65,Citation114,Citation123–Citation127 In patients with renal impairment, accumulation of morphine or codeine can cause severe adverse effects; administration of hydromorphone to patients with chronic renal failure can cause neuroexcitatory symptoms, including pain, cognitive impairments, and seizures.Citation114 The high variability in pharmacokinetics associated with methadone leads to recommendations against its use as a first-line agent among older patients.

Reviewing existing medications for interactions

Research indicates that nearly one in five patients take multiple opioid analgesics: 32% take more than five concurrent medications, and 21% take more than ten medications.Citation114,Citation128 Polypharmacy has been associated with poor adherence to treatment and increased potential risk of drug–drug interactions.Citation76,Citation129

Many prescription opioids undergo phase I metabolism mediated by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, especially CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. Multiple agents affect 3A4 activity. Fewer affect 2D6, but genetic variations in 2D6 expression may result in altered pharmacokinetics as well. Thus, agents metabolized this way may substantially increase the risk of drug–drug interactions and can influence the efficacy or tolerability of the agent.Citation114,Citation130–Citation133 For example, absorption of methadone is mediated by gastric pH and P-glycoprotein and is metabolized in part by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6, resulting in many potential drug interactions.Citation86 Morphine, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, and tapentadol are among the few opioid agents that undergo phase II hepatic metabolism via glucuronidation, bypassing CYP-mediated metabolism and thereby reducing the risk of drug–drug interactions involving the CYP450 system.Citation114,Citation123,Citation133–Citation136 However, the metabolites themselves may vary in biologic effect, activity, and potency, and therefore awareness of these pathways alone might not be sufficient in avoiding drug–drug interactions or the consequences of accumulated breakdown products.

Educating patients on alcohol use

Coadministration of prescription opioids with alcohol or other CNS depressants can exacerbate the respiratory depressant effects of opioids. Concurrent use of specific opioid-delivery systems with alcohol can also result in an increase in the release rate of the opioid, an effect known as “dose dumping,” resulting in absorption of a potentially fatal dose of the analgesic.Citation137 This phenomenon was observed with an ER formulation of hydromorphone (Palladone CL), leading to the removal of this product from the market.Citation138 Variable effects have been observed with an ER formulation of oxymorphone,Citation59,Citation139 although a new formulation is being developed that is more resistant to the effects of alcohol.Citation73 On the other hand, alcohol has not been found to alter appreciably the release characteristics of morphine sulfate ER capsules or OROS hydromorphone ER tablets.Citation137,Citation140–Citation142 Regardless of the pharmacokinetic effects, warnings concerning the coad-ministration of any opioid with alcohol are warranted, due to the pharmacodynamic effects and the combination of two CNS depressants.

Collecting complete histories of substance-use behavior

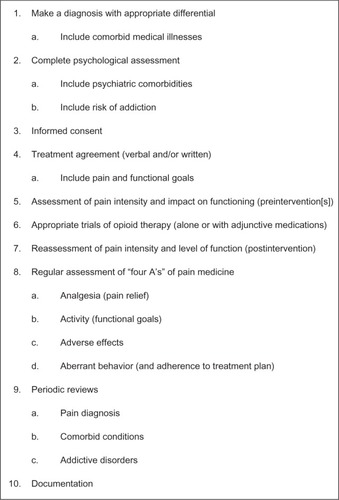

Balancing the risks and benefits of opioid analgesics, therefore, is essential in the management of pain with opioids. In recent decades, a structured approach to manage risk has been recommended ().Citation13,Citation33,Citation143 Clinicians can adopt a universal precautions approach, in which all patients who might benefit from prescription opioids undergo a substance-use assessment, using an appropriate minimum level of precaution ().Citation13,Citation33,Citation143 A number of rapid-assessment tools are amenable for use in the primary care setting, including the Opioid Risk ToolCitation144 and the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain.Citation145 Patients should be asked in a nonjudgmental manner about current and prior use of licit and illicit drugs, their willingness to see specialists if referred, and their willingness to participate in urine drug testing. Patients with current or a history of drug abuse can be safely treated with opioid analgesics, but typically require more careful monitoring.Citation146 However, those patients who demonstrate a high risk for misuse or abuse of opioids might not be appropriate candidates.Citation143 The high comorbidity between pain and psychiatric conditions, especially depression, leads to poorer prognoses for both conditionsCitation76 and might increase the patient’s risk for substance abuse or addiction.Citation114,Citation147 Clinicians need to continually monitor all patients, regardless of their age, for signs of tolerance, hyperalgesia, or drug abuse.Citation112

Figure 3 Ten steps of universal precautions in pain medicine.

Given the wide variability in response of patients to different opioids, selecting a specific agent that is effective and well tolerated in a given patient initiating opioid therapy represents yet another challenge.Citation132 Specific genetic polymorphisms have been identified that may explain some of this variability (eg, CYP2D6 polymorphisms that result in either rapid or slow drug metabolism can impact both the analgesic response to an opioid and the risk for adverse events),Citation132,Citation148–Citation150 but genetic testing is not yet routinely performed.Citation149 Accordingly, a trial of several different opioids may be necessary to find the appropriate regimen for an individual patient. In a retrospective chart review of patients with chronic pain initiated on opioid therapy, four opioid rotations were required in order for 80% of patients (cumulatively) to find an effective and well-tolerated opioid.Citation151 Only 36% of patients responded to the first opioid prescribed; approximately one-third discontinued treatment because of ineffectiveness, and another 30% because of side effects.Citation151

Incorporating regular urine screening

Urine toxicology screening can be of use in monitoring patients on long-term opioid therapy,Citation152 especially those at risk for aberrant behavior. Screening can help improve adherence to therapy by detecting use of prescribed medications, as well as illicit drug use. However, physicians should be aware of the limitations of screening: it is not particularly effective at detecting synthetic opioids, and cross-reactivity between drugs is common.Citation153

Planning to address side effects

Given that side effects frequently cause patients to discontinue opioid therapy, clinicians should assess and treat comorbidities and discontinue as appropriate current medications that contribute to the incidence and severity of side effects. Pharmacological approaches for preventing or treating opioid-induced side effects include symptomatic treatment (eg, antiemetics), switching route of administration, using an opioid-sparing regimen (eg, by addition of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent), or, as discussed above, switching to an alternative opioid.Citation15

Minimizing potential for abuse and diversion

The abuse liability of opioids has been well established. Opioids have mood-altering and anxiolytic effects that can induce euphoria, especially when plasma drug levels quickly rise.Citation154 However, the means of misuse and abuse differ depending upon an individual’s drug-use history. Experienced abusers are likely to manipulate the tablets (by crushing, injecting, or snorting) to obtain the greatest or fastest response, whereas less experienced users of prescription opioids are likely to misuse the agents by taking more than the recommended dose or by taking the prescribed dose more frequently than recommended. Consequently, rapid-acting IR formulations can be particularly attractive to experienced abusers. Similarly, the greater amount of active agent in ER formulations also makes them attractive to experienced abusers, and it makes these formulations potentially more lethal when abused. However, clinicians should be aware that the vast majority of opioid abuse is through oral use and does not entail tablet manipulation. Both forms of abuse are important to address, albeit through different venues. Conventional abuse of oral tablets can only be addressed through appropriate patient selection, counseling, and monitoring. Drug manufacturers are trying to address abuse through nonoral routes by developing ADFs. In addition, US governmental agencies have developed Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) that include, among other strategies, physician education and patient counseling.

Epidemiology of abuse

In the US, an increasing number of people are misusing prescription opioids.Citation26,Citation155–Citation157 The proportion of the US population aged 12 years or over that has ever used prescription pain relievers nonmedically increased from 30 million in 2002 to 35 million in 2010.Citation142 Among first-time users of illicit drugs, nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers was second only to marijuana use in 2009.Citation156 During the 7-year period between 2002 and 2009, the percentage of young adults aged 18–25 years who misused pain relievers increased from 4.1% to 4.8%, whereas the percentage who abused cocaine or methamphetamines decreased (from 2.0% to 1.5%, and from 0.6% to 0.2%, respectively).Citation156 College-age students have the highest prevalence rate of nonmedical use of opioids, which they predominantly obtained from friends or parents.Citation158 Abuse is not limited to young adults, and the rate of illicit drug use in adults aged 50–59 years increased from 2.7% to 5.8% between 2002 and 2010.Citation156 One study suggests that as many as 75% of patients with pain do not take their prescriptions as prescribed.Citation159 The prevalence of addiction in the general population is estimated at 10%; compared with general population samples, the frequency of opioid-use disorders is substantially elevated among patients receiving opioid therapy.Citation160–Citation163

Essentially three types of persons abuse or misuse opioid drugs: patients receiving pain medication who also abuse (those who obtain the drug legally for medical use but use it unsafely or in ways not prescribed), recreational drug abusers who obtain the drug illegally for experimentation or to get high, and experienced drug abusers.Citation164 Patients with pain typically fall into the first category: their most common means of misuse or abuse is through oral administration, by taking more of the medication at or above the recommended doses using the normal route of administration, or by taking the pills when not in pain.Citation158,Citation165,Citation166 This use may be for euphoria, to address other complaints such as anxiety or insomnia (referred to as chemical coping), or for undertreated pain. In contrast, recreational and experienced drug abusers who use opioids may be more likely to alter the drug to change the route of administration.Citation167 By altering sustained-release formulations through crushing, snorting, or injecting, a greater portion of the drug can be released than originally intended, to provide the high.Citation154,Citation164,Citation165

Identifying patients at elevated risk of progressing from misuse to abuse is imperative. The boxed warning on all prescription-opioid agents highlights that persons with a personal or family history of substance abuse or mental illness (including but not limited to depression) are at increased risk for opioid abuse.Citation113 Other potential risk factors include patients with other medical or psychiatric comorbidities and patients with (typically undertreated) significant levels of pain.Citation4,Citation168,Citation169 Aberrant behaviors that suggest misuse or abuse include the use of pain medications for reasons other than pain, evidence of impaired control, compulsive use of the medication, continued use of the opioid agent despite a lack of benefit or a risk of harm, calling for early refills, “losing” prescriptions, or other drug-seeking behaviors, including “doctor shopping.”Citation170

Source of abused prescription opioids

While the most common motives for opioid abuse include relieving pain, getting high, or experimentation, the most common source of prescription opioids used for nonmedical purposes is from a friend or relative – for free – the majority of whom had originally received the drug as a prescription from one physician.Citation21,Citation154,Citation156,Citation158 Fewer than 5% of persons over age 12 years have obtained a prescription pain reliever from a drug dealer or stranger.Citation21,Citation156 Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions report that prescription-opioid abusers are more likely to be white, male, and college-educated adults.Citation171 What is unclear is whether the source of the drug is from a legitimate prescriber or from a source that is or is likely an illegitimate prescribing source (ie, so-called pill mills). Recent arrests in Florida highlight the concern of legitimate pain clinics compared to those solely dealing in the illegal prescribing of opioids.Citation172

Pharmacokinetic factors

Specific drug factors that influence the abuse liability of an agent include its intrinsic pharmacologic activity, its physicochemical properties, and its pharmacokinetic properties (ie, absorption, distribution, biotransformation, excretion).Citation173 Regarding pharmacokinetic parameters, increases in Cmax and decreases in Tmax have been associated with greater abuse potential of an opioid formulation.Citation164,Citation174 The ratio between these two factors (Cmax/Tmax) has been advanced as a common metric to quantify the abuse potential of a particular formulation, although additional research is necessary to assess the validity of this “abuse quotient.” Consistent with findings from the controlled human abuse-liability studies above, veteran abusers indicate that “attractive” agents are those that produce a rapid onset and a sustained duration of effect.Citation175 In contrast, unattractive attributes, such as withdrawal effects, slow onset of effect, unpleasantness of administration, and other negative formulation issues, have been associated with reduced abuse potential.Citation175

Abuse-deterrent formulations

Altering formulations to address the problem of overcon-sumption, either unintentional or intentional, is not currently possible.Citation164 However, drug manufacturers are now developing ADFs with the aim of either making opioid analgesics less attractive for nonoral abuse or increasing the consequences of abuse, ultimately to minimize the abuse of opioids among recreational reward-seekers. Current ER opioid formulations maintain constant plasma levels for prolonged periods, thereby reducing the euphoric effects of the drug through less rapid rises in plasma levels and lower peak levels.Citation35,Citation176 The current approaches for ADFs or abuse-resistant formulations involve including physical barriers to tampering, agonist–antagonist formulations (eg, adding naltrexone), modified-release formulations, and formulations that are or become highly viscous when attempts are made to defeat the ER mechanisms.Citation154,Citation164,Citation177,Citation178 Examples include the currently available OROS hydromorphone ER (Exalgo), the new OxyContin formulation that has tamper-resistant properties, and a number of possible formulations currently under investigation: oxycodone ER in high-viscosity hard gelatin capsules (Remoxy; Pain Therapeutics, Austin, TX, USA); two oral oxycodone formulations using the DETERx tamper-resistant formulation (COL-003 and COL-172; Collegium Pharmaceutical, Cumberland, RI, USA); and an oxycodone formulation combined with naltrexone (OxyNal, Elite Pharmaceuticals, Northvale, NJ, USA; PTI-801 or Oxytrex, Pain Therapeutics).Citation21

A study that compared the abuse potential of OROS hydromorphone ER with IR hydromorphone among subjects with a history of recreational opioid use showed that the delayed onset of good drug effects and prominent bad drug effects of the OROS ER formulation was likely to decrease its potential for abuse.Citation35 The hard outer shell of the OROS hydromorphone ER tablet further minimizes its abuse potential by making the tablet substantially more difficult to manipulate through chewing or biting.Citation78 In addition, research indicates that only 50% of active ingredient was recovered after 24 hours of immersion in water, and only 30% was recovered after milling.Citation78 Another ADF involves embedding pellets of ER morphine sulfate with a sequestered core of naltrexone (MS-sNT, Embeda): naltrexone is released if the capsule is crushed, mitigating any morphine-induced effects.Citation179 This formulation is currently not being marketed. There are, as yet, no data establishing an increased efficacy or decreased risk of misuse or abuse with this formulation.Citation180

A controlled-release formulation of oxycodone has been associated with less drug-liking than the IR formulation when intact tablets are taken whole, requiring nearly twofold-higher doses to achieve comparable subjective effects.Citation176 In an effort to curb the widespread nonmedical use and abuse of controlled-release oxycodone, the FDA approved a new tamper-resistant formulation in 2010.Citation181 The controlled-release polymer system of the new formulation makes the tablet more difficult to crush, chew, dissolve, or melt, potentially discouraging injection and inhalation.Citation20,Citation181 Recent data from 103 opioid-dependent patients entering treatment programs in the United States showed that reporting of controlled-release oxycodone as the primary drug of abuse decreased from 35.6% of respondents before release of the new formulation to 12.8% 21 months later (P < 0.001),Citation20 supporting the utility of tamper-resistant properties in curbing abuse. A water-insoluble oral formulation of oxycodone ER is also currently in development. Research suggests this formulation (either whole or chewed) has a significantly lower abuse potential on a drug-liking subscale compared with either oxycodone ER or oxycodone IR, when manipulated.Citation36

In summary, ADFs are an incremental improvement that may decrease certain forms of abuse involving tablet manipulation. However, because oral abuse is more common, it is important for clinicians to adhere to best-practice guidelines for prescribing opioids, which include stratifying patients according to risk, counseling patients about the risks of their medications, and periodically monitoring and reassessing patients for signs of misuse or abuse. Unfortunately, it is not possible for ADFs to fully address the problems of abuse, misuse, or diversion. While these formulations may offer additional deterrence, clinicians should not have a false sense of security associated with ADFs.

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies

The goal of REMS is to ensure that a drug’s benefits outweigh any risks in clinical practice.Citation21 To address the escalating problem of prescription-drug abuse, the FDA has proposed a prescription-drug abuse-prevention plan that includes opioid REMS, patient–provider agreements and guidelines, an increased use of prescription-drug monitoring programs, and establishing regulations for controlled-substance prescription drugs.Citation182,Citation183 Toward this end, physicians may be required to undergo mandatory education, provide patient education, and potentially enroll patients into registries.Citation155,Citation182 A government blueprint has been created that emphasizes that health-care professionals have a responsibility to ensure the safe and effective use of ER opioid analgesics, and that providers are knowledgeable about these agents.Citation113

The four main components of this blueprint comprise patient screening, initiating and discontinuing treatment, managing opioid treatment (including goal-setting), and counseling patients about appropriate opioid use. When assessing patients for possible treatment with ER opioid analgesics, clinicians are recommended to assess the potential risks against the potential benefits of prescription-opioid use, and to determine the individual patient’s risk of abuse and tolerance for opioids.

Physicians should be aware of current regulations and appropriate dose selection and titration of opioid therapies. This includes familiarity with converting from IR to ER formulations, as well as equianalgesic dosing concepts. While managing patients on opioid therapy, clinicians must focus on appropriate goal-setting and integrating patient–provider agreements and prescription-drug monitoring programs. In addition, clinicians should be familiar with how to manage adverse events and tolerance, and should continue to monitor the patient’s symptoms and any underlying medical conditions. During chronic treatment, physicians should periodically assess continuing requirements for opioid analgesia on an individual patient basis.

Of particular importance is the need to counsel patients and their caregivers adequately regarding the safe use, storage, and disposal of ER opioids. Proper disposal of unused medicine is essential for preventing unintentional overdose. Although most medications can be disposed of in the household trash (after mixing them with an unpalatable substance such as coffee grounds and sealing the mixture in a bag) or taken to drug “take-back” programs in the community, for controlled substances such as strong ER opioids, the FDA recommends flushing the unused medication to reduce risk of exposure to patients’ household members.Citation184

These processes embody many best practices recommended by numerous authors for the safe use of opioids.Citation13,Citation143 However, the degree to which REMS and other opioid-prescribing guidelines will impact the upward trend in opioid prescribing is unknown.

Conclusion

Chronic pain is a substantial problem that is likely to continue growing with the aging of the American population. It is currently underdiagnosed and undertreated, leading to substantial burdens on both the personal and the national level. Appropriate management typically includes the use of prescription-opioid analgesics; however, many clinicians remain hesitant and confused about the proper use of opioid analgesics. In addition to proper patient selection and ongoing monitoring, new formulations using ER technologies and other abuse-deterrent approaches may help combat the growing risk of abuse or misuse.

Acknowledgments

Technical editorial and medical writing support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Lynne Kolton Schneider, PhD, and Synchrony Medical Communications, LLC, West Chester, PA, USA. Funding for this support was provided by Mallinckrodt Inc, the Pharmaceuticals business of Covidien, Hazelwood, MO, USA.

Disclosure

Dr Brennan reports serving as a consultant or speaker for Apricus Biosciences, Covidien Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Endo Pharmaceuticals, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Insys Therapeutics, Johnson and Johnson, Purdue Pharma, and Teva Pharmaceuticals.

References

- Institute of Medicine of the National AcademiesRelieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and ResearchWashingtonIOM2011 Available from: http://www.iom.edu/relievingpainAccessed October 12, 2011

- CroftPBlythFMvan der WindtDThe global occurrence of chronic pain: an introductionCroftPBlythFMvan der WindtDChronic Pain Epidemiology: From Aetiology to Public HealthOxfordOxford University Press2010918

- BreivikHCollettBVentafriddaVCohenRGallacherDSurvey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatmentEur J Pain20061028733316095934

- CiceroTJSurrattHLKurtzSEllisMSInciardiJAPatterns of prescription opioid abuse and comorbidity in an aging treatment populationJ Subst Abuse Treat201242879421831562

- NicholsonBBenefits of extended-release opioid analgesic formulations in the treatment of chronic painPain Pract20089718119019047

- GurejeOVon KorffMSimonGEGaterRPersistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization study in primary careJAMA19982801471519669787

- GurejeOSimonGEVon KorffMA cross-national study of the course of persistent pain in primary carePain20019219520011323140

- BreuerBCrucianiRPortenoyRKPain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national surveySouth Med J201010373874720622716

- KuehnBMOpioid prescriptions soar: increase in legitimate use as well as abuseJAMA200729724925117227967

- MoskovitzBLBensonCJPatelAAAnalgesic treatment for moderate-to-severe acute pain in the United States: patient perspectives in the Physicians Partnering Against Pain (P3) surveyJ Opioid Manag2011727728621957827

- ManchikantiLSinghVDattaSCohenSPHirschJAComprehensive review of epidemiology, scope, and impact of spinal painPain Physician200912E35E7019668291

- ManchikantiLAbdiSAtluriSAmerican Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part 2 – guidancePain Physician201215S67S11622786449

- ChouRFanciulloGJFinePGClinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer painJ Pain20091011313019187889

- American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older PersonsPharmacological management of persistent pain in older personsPain Med2009101062108319744205

- McNicolEOpioid side effects and their treatment in patients with chronic cancer and noncancer painJ Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother20082227028121923311

- ChanBKBTamLKWatCYChungYFTsuiSLCheungCWOpioids in chronic non-cancer painExpert Opin Pharmacother20111270572021254859

- ManchikantiLAilinaniHKoyyalaguntaDA systematic review of randomized trials for long-term opioid management for chronic non-cancer painPain Physician2011149112121412367

- StannardCFOpioids for chronic pain: promise and pitfallsCurr Opin Support Palliat Care2011515015721430541

- AngstMSChuLFTingleMSShaferSLClarkJDDroverDRNo evidence for the development of acute tolerance to analgesic, respiratory depressant and sedative opioid effects in humansPain2009142172619135798

- CiceroTJEllisMSEffect of abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContinN Engl J Med201236718718922784140

- WebsterLSt MarieBMcCarbergBPassikSDPanchalSJVothECurrent status and evolving role of abuse-deterrent opioids in managing patients with chronic painJ Opioid Manag2011723524521823554

- LeverenceRRWilliamsRLPotterMChronic non-cancer pain: a siren for primary care – a report from the Primary Care Multiethnic Network (PRIME Net)J Am Board Fam Med20112455156121900438

- FischMJLeeJWWeissMProspective, observational study of pain and analgesic prescribing in medical oncology outpatients with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancerJ Clin Oncol2012301980198822508819

- PappagalloMIncidence, prevalence, and management of opioid bowel dysfunctionAm J Surg200118211S18S11755892

- TrescotAMDattaSLeeMHansenHOpioid pharmacologyPain Physician200811S133S15318443637

- ArgoffCESilversheinDIA comparison of long- and short-acting opioids for the treatment of chronic noncancer pain: tailoring therapy to meet patient needsMayo Clin Proc20098460261219567714

- PortenoyRKSciberrasAEliotLLoewenGButlerJDevaneJSteady-state pharmacokinetic comparison of a new, extended-release, once daily morphine formulation, Avinza, and a twice-daily controlled-release morphine formulation in patients with chronic moderate-to-severe painJ Pain Symptom Manage20022329230011997198

- CaldwellJRHaleMEBoydRETreatment of osteoarthritis pain with CR oxycodone or fixed combination oxycodone plus acetaminophen added to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a double blind, randomized, multicenter, placebo controlled trialJ Rheumatol19992686286910229408

- HagenNAThirlwellMEisenhofferJQuigleyPHarsanyiZDarkeAEfficacy, safety, and steady-state pharmacokinetics of once-a-day controlled-release morphine (MS Contin XL) in cancer painJ Pain Symptom Manage200529809015652441

- CarsonSThakurtaSLowASmithBChouRDrug class review Long-acting opioid analgesics. Final update 6 reportPortland (OR)Oregon Health and Science University2011 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62335Accessed September 14, 2012

- ColuzziFMattiaCOxycodone. Pharmacological profile and clinical data in chronic pain managementMinerva Anestesiol20057145146016012419

- BohnertASValensteinMBairMJAssociation between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deathsJAMA20113051315132121467284

- FinePGMahajanGMcPhersonMLLong-acting opioids and short-acting opioids: appropriate use in chronic pain managementPain Med200910Suppl 2S79S8819691687

- GourlayGKSustained relief of chronic pain. Pharmacokinetics of sustained release morphineClin Pharmacokinet1998351731909784932

- ShramMJSathyanGKhannaSEvaluation of the abuse potential of extended release hydromorphone versus immediate release hydromorphoneJ Clin Psychopharmacol201030253320075644

- SetnikBRolandCLClevelandJMWebsterLThe abuse potential of Remoxy, an extended-release formulation of oxycodone, compared with immediate- and extended-release oxycodonePain Med20111261863121463474

- DuensingLEksterowiczNMacarioABrownMSternLOgbonnayaAPatient and physician perceptions of treatment of moderate-to-severe chronic pain with oral opioidsCurr Med Res Opin2010261579158520429822

- HaleMKhanAKutchMLiSOnce-daily OROS hydromorphone ER compared with placebo in opioid-tolerant patients with chronic low back painCurr Med Res Opin2010261505151820429852

- GordonACallaghanDSpinkDBuprenorphine transdermal system in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled crossover study, followed by an open-label extension phaseClin Ther20103284486020685494

- WildJEGrondSKuperwasserBLong-term safety and tolerability of tapentadol extended release for the management of chronic low back pain or osteoarthritis painPain Pract20101041642720602712

- FriedmannNKlutzaritzVWebsterLLong-term safety of Remoxy (extended-release oxycodone) in patients with moderate to severe chronic osteoarthritis or low back painPain Med20111275576021481168

- WallaceMThipphawongJOpen-label study on the long-term efficacy, safety, and impact on quality of life of OROS hydromorphone ER in patients with chronic low back painPain Med2010111477148821199302

- PergolizziJAlonEBaronRTapentadol in the management of chronic low back pain: a novel approach to a complex condition?J Pain Res2011420321021887117

- ChaoJRetrospective analysis of Kadian (morphine sulfate sustained-release capsules) in patients with chronic, nonmalignant painPain Med2005626226515972090

- MatsumotoAKBabulNAhdiehHOxymorphone extended-release tablets relieve moderate to severe pain and improve physical function in osteoarthritis: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled phase III trialPain Med2005635736616266356

- GibofskyABarkinRLChronic pain of osteoarthritis: considerations for selecting an extended-release opioid analgesicAm J Ther20081524125518496262

- KatzNSunSJohnsonFStaufferJAOL-01 (morphine sulfate and naltrexone hydrochloride) extended-release capsules in the treatment of chronic pain of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safetyJ Pain20101130331119944650

- FashnerJBellALHerpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia: prevention and managementAm Fam Physician2011831432143721671543

- MoulinDERicharzUWallaceMJacobsAThipphawongJEfficacy of the sustained-release hydromorphone in neuropathic pain management: pooled analysis of three open-label studiesJ Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother20102420021220718640

- HermannsKJunkerUNolteTProlonged-release oxycodone/naloxone in the treatment of neuropathic pain – results from a large observational studyExpert Opin Pharmacother20121329931122224497

- VictorTWAlvarezNAGouldEOpioid prescribing practices in chronic pain management: guidelines do not sufficiently influence clinical practiceJ Pain2009101051105719595639

- SloanPABarkinRLOxymorphone and oxymorphone extended release: a pharmacotherapeutic reviewJ Opioid Manag2008413114418717508

- Facts and Comparisons [homepage on the Internet] Available from: http://www.factsandcomparisons.com/index.aspxSt LouisWolters Kluwer HealthAccessed December 29, 2012

- King PharmaceuticalsAvinza (morphine sulfate extended-release capsules): US prescribing informationBristol (TN)King Pharmaceuticals2008

- King PharmaceuticalsEmbeda (morphine sulfate and naltrexone hydrochloride) extended-release capsules: US prescribing informationBristol (TN)King Pharmaceuticals2012

- Actavis ElizabethKadian (morphine sulfate) extended-release capsules: US prescribing informationMorristown (NJ)Actavis Elizabeth2012

- Purdue PharmaMS Contin (morphine sulfate controlled-release) tablets: US prescribing informationStamford (CT)Purdue Pharma2009

- Xanodyne PharmaceuticalsOramorph SR (morphine sulfate) tablets: US prescribing informationNewport (KY)Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals2006

- Endo PharmaceuticalsOpana ER (oxymorphone hydrochloride) extended-release tablets: US prescribing informationChadds Ford (PA)Endo Pharmaceuticals2012

- Mallinckrodt Brand PharmaceuticalsExalgo (hydromorphone hydrochloride) extended-release tablets: US prescribing informationHazelwood (MO)Mallinckrodt Brand Pharmaceuticals2012

- Janssen PharmaceuticalsNucynta ER (tapentadol) extended-release oral tablets: US prescribing informationTitusville (NJ)Janssen Pharmaceuticals2012

- Purdue PharmaOxyContin (oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release) tablets: US prescribing informationStamford (CT)Purdue Pharma2012

- Roxane LaboratoriesDolophine (methadone hydrochloride) tablets: US prescribing informationColumbus (OH)Roxane Laboratories2012

- Mallinckrodt Brand PharmaceuticalsMethadose oral tablets (methadone hydrochloride tablets USP): US prescribing informationHazelwood (MO)Mallinckrodt Brand Pharmaceuticals2012

- Janssen PharmaceuticalsDuragesic (fentanyl transdermal system): US prescribing informationTitusville (NJ)Janssen Pharmaceuticals2012

- Purdue PharmaButrans (buprenorphine) transdermal system: US prescribing informationStamford (CT)Purdue Pharma2012

- KnotkovaHFinePGPortenoyRKOpioid rotation: the science and the limitations of the equianalgesic dose tableJ Pain Symptom Manage20093842643919735903

- AdamsEHChwieckoPAce-WagonerYA study of Avinza (morphine sulfate extended-release capsules) for chronic moderate-to-severe noncancer pan conducted under real-world treatment conditions –the ACCPT StudyPain Pract2006625426417129306

- CaldwellJRRapoportRJDavisJCEfficacy and safety of a once-daily morphine formulation in chronic, moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis pain: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial and an open-label extension trialJ Pain Symptom Manage20022327829111997197

- MatsumotoAKOral extended-release oxymorphone: a new choice for chronic pain reliefExpert Opin Pharmacother200781515152717661733

- HaleMEDvergstenCGimbelJEfficacy and safety of oxymorphone extended release in chronic low back pain: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled phase III studyJ Pain20056212815629415

- BenedekIHJobesJXiangQFiskeWDBioequivalence of oxymorphone extended release and crush-resistant oxymorphone extended releaseDrug Design Devel Ther20115455463

- FiskeWDJobesJXiangQChangSCBenedekIHThe effects of ethanol on the bioavailability of oxymorphone extended-release tablets and oxymorphone crush-resistant extended-release tabletsJ Pain201213909922208805

- MooreKTSt-FleurDMarriccoNCSteady-state pharmacokinetics of extended-release hydromorphone (OROS hydromorphone): a randomized study in healthy volunteersJ Opioid Manag2010635135821046932

- WallaceMRauckRLMoulinDThipphawongJKhannaSTudorICOnce-daily OROS hydromorphone for the management of chronic nonmalignant pain: a dose-conversion and titration studyInt J Clin Pract2007611671167617877652

- LussierDRicharzUFincoGUse of hydromorphone, with particular reference to the OROS formulation, in the elderlyDrugs Aging20102732733520361803

- SathyanGXuEThipphawongJGuptaSKPharmacokinetic investigation of dose proportionality with a 24-hour controlled-release formulation of hydromorphoneBMC Clin Pharmacol20077317270058

- PandePHinesJWBrogranAPTamper-resistant properties of once-daily hydromorphone ER (OROS hydromorphone ER)Paper presented at the American Pain Society 30th Annual Scientific MeetingMay 19–21, 2011Austin, USA

- WallaceMRauckRLMoulinDThipphawongJKhannaSTudorICConversion from standard opioid therapy to once-daily oral extended-release hydromorphone in patients with chronic cancer painJ Internat Med Res200836343352

- HartrickCTRozekRJTapentadol in pain management: a mu-opioid receptor agonist and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitorCNS Drugs20112535937021476608

- HartrickCTRodriguez HernandezJRTapentadol for pain: a treatment evaluationExpert Opin Pharmacother20121328328622192161

- RiemsmaRForbesCHarkerJSystematic review of tapentadol in chronic severe painCurr Med Res Opin2011271907193021905968

- VadiveluNTimchenkoAHuangYSinatraRTapentadol extended-release for treatment of chronic pain: a reviewJ Pain Res2011421121821887118

- EtropolskiMKellyKOkamotoARauschkolbCComparable efficacy and superior gastrointestinal tolerability (nausea, vomiting, constipation) of tapentadol compared with oxycodone hydrochlorideAdv Ther201128410417

- CepedaMSSuttonAWeinsteinRKimMEffect of tapentadol extended release on productivity: results from an analysis combining evidence from multiple sourcesClin J Pain20122881321646907

- ToombsJDKralLAMethadone treatment for pain statesAm Fam Physician2005711353135815832538

- WebsterLRCochellaSDasguptaNAn analysis of the root causes for opioid-related overdose deaths in the United StatesPain Med201112Suppl 2S26S3521668754

- MuijsersRBRWagstaffAJTransdermal fentanyl: an updated review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in chronic cancer pain controlDrugs2001612289230711772140

- HansGRobertDTransdermal buprenorphine – a critical appraisal of its role in pain managementJ Pain Res2009211713421197300

- NelsonLSchwanerRTransdermal fentanyl: pharmacology and toxicologyJ Med Toxicol2009523024119876859

- HairPIKeatingGMMcKeageKTransdermal matrix fentanyl membrane patch (Matrifen) in severe cancer-related chronic painDrugs2008682001200918778121

- MarierJ-FLorMMorinJComparative bioequivalence study between a novel matrix transdermal delivery system of fentanyl and a commercially available reservoir formulationBr J Clin Pharmacol20066312112416939522

- MooreKTAdamsHDNatarajanJAriyawansaJRichardsHMBioequivalence and safety of a novel fentanyl transdermal matrix system compared with a transdermal reservoir systemJ Opioid Manag201179910721561033

- [No authors listed]Fentanyl patches: preventable overdosePrescrire Int201019222520455338

- MooreKTSathyanGRicharzUNatarajanJVandenbosscheJRandomized 5-treatment crossover study to assess the effects of external heat on serum fentanyl concentrations during treatment with transdermal fentanyl systemsJ Clin Pharmacol2011521174118521878578

- ColeJMBestBMPesceAJVariability of transdermal fentanyl metabolism and excretion in pain patientsJ Opioid Manag20106293920297612

- PloskerGLBuprenorphine 5, 10, and 20 micrograms/h transdermal patch: a review of its use in the management of chronic non-malignant painDrugs2011712491250922141389

- CowanALewisJWMacfarlaneIRAgonist and antagonist properties of buprenorphine: a new antinociceptive agentBr J Pharmacol197760537545409448

- SchutterURitzdorfIHeckesBThe transdermal 7-day buprenorphine patch – an effective and safe treatment of pain if tramadol or tilidate/naloxone is insufficient. Results of a non-interventional studyMMW Fortschr Med2010152Suppl 26269 German21591321

- SteinerDMuneraCHaleMRipaSLandauCEfficacy and safety of buprenorphine transdermal system (BTDS) for chronic moderate to severe low back pain: a randomized, double-blind studyJ Pain2011121163117321807566

- SteinerDJSitarSWenWEfficacy and safety of the seven-day buprenorphine transdermal system in opiate-naïve patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain: an enriched, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Pain Symptom Manage20114290391721945130

- NordboASkurtveitSBorchgrevinkPCKaasaSFredheimOMLow-dose transdermal buprenorphine – long-term use and co-medication with other potentially addictive drugsActa Anaesthesiol Scand201256889422092357

- McCrackenLMIversonGLDisrupted sleep patterns and daily functioning in patients with chronic painPain Res Manag20027757912185371

- KosinskiMJaganapCGajriaKScheinJFreedmanJPain relief and pain-related sleep disturbance with extended-release tramadol in patients with osteoarthritisCurr Med Res Opin2007231615162617559754

- TangNKWrightKJSalkovskisPMPrevalence and correlates of clinical insomnia co-occurring with chronic back painJ Sleep Res200716859517309767

- BinsfeldHSzczepanskiLWaechterSRicharzUSabatowskiRA randomized study to demonstrate noninferiority of once-daily OROS hydromorphone with twice-daily sustained-release oxycodone for moderate to severe chronic noncancer painPain Pract20101040441520384968

- RauckRLWhat is the case for prescribing long-acting opioids over short-acting opioids for patients with chronic pain? A critical reviewPain Pract2009946847919874536

- RosenthalMMoorePGrovesESleep improves when patients with chronic OA pain are managed with morning dosing of once a day extended-release morphine sulfate (Avinza): findings from a pilot studyJ Opioid Manag2007314515418027540

- SittlRTransdermal buprenorphine in the treatment of chronic painExpert Rev Neurother2005531532315938664

- KornickCASantiago-PalmaJMorylNPayneRObbensEABenefit-risk assessment of transdermal fentanyl for the treatment of chronic painDrug Saf20032695197314583070

- RauckRLBookbinderSABunkerTRA randomized, open-label, multicenter trial comparing once-a-day Avinza (morphine sulfate extended-release capsules) versus twice-a-day OxyContin (oxycodone hydrochloride controlled-release tablets) for the treatment of chronic, moderate to severe low back pain: improved physical functioning in the ACTION trialJ Opioid Manag20073354317367093

- GraziottinAGardner-NixJStumpfMBerlinerMNOpioids: how to improve compliance and adherencePain Pract20111157458121410639

- US Food and Drug AdministrationRisk evaluation and mitigation strategies (REMS) for extended-release and long-acting opioids2012 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/UCM311290.pdfAccessed November 21, 2012

- SmithHBruckenthalPImplications of opioid analgesia for medically complicated patientsDrugs Aging20102741743320450239

- DosaDMDoreDDMorVTenoJMFrequency of long-acting opioid analgesic initiation in opioid-naïve nursing home residentsJ Pain Symptom Manage20093851552119375273

- RazaqMBalicasMMankanNUse of hydromorphone (Dilaudid) and morphine for patients with hepatic and renal impairmentAm J Ther20071441441617667220

- PergolizziJVJrLabhsetwarSAPuenpatomRAJooSBen-JosephRHSummersKHPrevalence of exposure to potential CYP450 pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions among patients with chronic low back pain taking opioidsPain Pract20111123023920807350

- PeacockWFHollanderJEDiercksDBMorphine and outcomes in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE analysisEmerg Med J20082520520918356349

- GruberEMTschernkoEMAnaesthesia and postoperative analgesia in older patients with chronic obstructive analgesia in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: special considerationsDrugs Aging20032034736012696995

- BellvilleJWEscarragaLAWallensteinSLRelative respiratory depressant effects of oxymorphone (Numorphan) and morphineAnesthesiology19602139740013798620

- MurtaghFEChaiMODonohoePThe use of opioid analgesia in end-stage renal disease patients managed without dialysis: recommendations for practiceJ Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother20072151617844723

- TegederILotschJGeisslingerGPharmacokinetics of opioids in liver diseaseClin Pharmacokinet199937174010451781

- Purdue PharmaDilaudid (hydromorphone hydrochloride) oral liquid and tablets: US prescribing informationStamford (CT)Purdue Pharma2008

- WolffJBiglerDChristensenCBInfluence of renal function on the elimination of morphine and morphine glucoronidesEur J Clin Pharmacol1988343533573402521

- BabulNDurkeACHagenNHydromorphone metabolite accumulation in renal failureJ Pain Symptom Manage1995101841867543126

- GuayDRAwniWMFindlayJWPhamacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of codeine in end-stage renal diseaseClin Pharmacol Ther19884363713335120

- BarkinRLExtended-release tramadol (Ultram ER): a pharmacotherapeutic, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamics focus on effectiveness and safety in patients with chronic/persistent painAm J Ther20081515716618356636

- Parsells KellyJCookSFKaufmanDWPrevalence and characteristics of opioid use in the US adult populationPain200813850751318342447

- JansàMHernándezCVidalMMultidimensional analysis of treatment adherence in patients with multiple chronic conditions. A cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospitalPatient Educ Couns20108116116820167450

- FosterAMobleyEWangZComplicated pain management in a CYP4502D6 poor metabolizerPain Pract2007735235617986163

- SusceMTMurray-CarmichaelEDe LeonJResponse to hydrocodone, codeine and oxycodone in a CYP2D6 poor metabolizerProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry2005301356135816631290

- SmithHSOpioid metabolismMayo Clin Proc20098461362419567715

- AdamsMPieniaszekHJJrGammaitoniAROxymorphone extended release does not affect CYP2C9 or CCYP3A4 metabolic pathwaysJ Clin Pharmacol20054533734515703368

- CoffmanBLRiosGRKingCDHuman UGT287 catalyzes morphine glucuronidationDrug Metab Dispos199725149010622

- De WildtSNKearnsGLLeederJSGlucoronidation in humans: pharmacogenetic and developmental aspectsClin Pharmacokinet19993643945210427468

- SinatraROpioid analgesics in primary care: challenges and new advances in the management of noncancer painJ Am Board Fam Med20061916517716513905

- SathyanGSivakumarKThipphawongJPharmacokinetic profile of a 24-hour controlled-release OROS formulation of hydromorphone in the presence of alcoholCurr Med Res Opin20082429730518062845

- US Food Drug AdministrationFDA alert. Alcohol–Palladone interaction Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/Drug-Safety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm129288.htmAccessed January 28, 2013

- WaldenMNichollsFASmithKJTuckerGTThe effect of ethanol on the release of opioids from oral prolonged-release preparationsDrug Devel Indust Pharm20073311011111

- BarkinRLShiraziDKinzlerEEffect of ethanol on the release of morphine sulfate from Oramorph SR tabletsAm J Ther20091648248619770796

- JohnsonFWagnerGSunSStaufferJEffect of concomitant ingestion of alcohol on the in vivo pharmacokinetics of Kadian (morphine sulfate extended-release) capsulesJ Pain2008933033618201934

- GuayDROral hydromorphone extended-releaseConsult Pharm20102581682821172762

- GourlayDLHeitHAAlmahreziAUniversal precautions in pain medicine: a rational approach to the treatment of chronic painPain Med2005610711215773874

- WebsterLRWebsterRMPredicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk ToolPain Med200569643244216336480

- ButlerSFBudmanSHFernandezKCFanciulloGJJamisonRNCross-validation of a screener to predict opioid misuse in chronic pain patients (SOAPP-R)J Addict Med20093667320161199

- PassikSDKirshKLWhitcombLA new tool to assess and document pain outcomes in chronic pain patients receiving opioid therapyClin Ther20042655256115189752

- EdlundMJSteffickDHudsonTRisk factors for clinically recognized opioid abuse and dependence among veterans using opioids for chronic non-cancer painPain200712835536217449178

- ZangerUMRaimundoSEichelbaumMCytochrome P450 2D6: overview and update on pharmacology, genetics, biochemistryNaunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol2004369233714618296

- ZhouSFPolymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2D6 and its clinical significance: part 1Clin Pharmacokinet20094868972319817501

- KirchheinerJSchmidtHTzvetkovMPharmacokinetics of codeine and its metabolite morphine in ultra-rapid metabolizers due to CYP2D6 duplicationPharmacogenomics J2007725726516819548

- Quang-CantagrelNDWallaceMSMagnusonSKOpioid substitution to improve the effectiveness of chronic noncancer pain control: a chart reviewAnesth Analg20009093393710735802

- KatzNFanciulloGJRole of urine toxicology testing in the management of chronic opioid therapyClin J Pain200218S76S8212479257

- ManchikantiLAtluriSTrescotAMGiordanoJMonitoring opioid adherence in chronic pain patients: tools, techniques, and utilityPain Physician200811S155S18018443638

- WoolfCJHashmiMUse and abuse of opioid analgesics: potential methods to prevent and deter non-medical consumption of prescription opioidsCurr Opin Investig Drugs200456166

- US Food and Drug AdministrationJoint meeting of the Anesthetic and Life Support Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee: Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) for extended-release and long-acting opioid analgesics2010 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrugClass/ucm217510.pdfAccessed September 6, 2012

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services AdministrationResults from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National FindingsRockville (MD)Office of Applied Studies2011 Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/2k10nsduh/2k10results.htmAccessed July 30, 2012

- ManchikantiLSinghATherapeutic opioids: a ten-year perspective on the complexities and complications of the escalating use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioidsPain Physician200811S63S8818443641

- McCabeSECranfordJABoydCJTeterCJMotives, diversion and routes of administration associated with nonmedical use of prescription opioidsAddict Behav20073256257516843611

- CoutoJERomneyMCLeiderHLSharmaSGoldfarbNIHigh rates of inappropriate drug use in the chronic pain populationPopul Health Manag20091218519019663620

- ChabalCErjavecMKJacobsonLMarianoAChaneyEPrescription opiate abuse in chronic pain patients: clinical criteria, incidence, and predictorsClin J Pain1997131501559186022

- ManchikantiLPampatiVDamronKSFellowsBBarnhillRCBeyerCPrevalence of opioid abuse in interventional pain medicine practice settings: a randomized clinical evaluationPain Physician2001435836516902682

- KatzNPSherburneSBeachMBehavioral monitoring and urine toxicology testing in patients receiving long-term opioid therapyAnesth Analg2003971097110214500164

- FlemingMFBalousekSLKlessigCLMundtMPBrownDDSubstance use disorders in a primary care sample receiving daily opioid therapyJ Pain2007857358217499555

- WebsterLRBathBMedveRAOpioid formulations in development designed to curtail abuse: who is the target?Expert Opin Investig Drugs200918255263

- KatzNDartRCBaileyETrudeauJOsgoodEPaillardFTampering with prescription opioids: nature and extent of the problem, health consequences, and solutionsAm J Drug Alcohol Abuse20113720521921517709