Abstract

Every body structure is wrapped in connective tissue, or fascia, creating a structural continuity that gives form and function to every tissue and organ. Currently, there is still little information on the functions and interactions between the fascial continuum and the body system; unfortunately, in medical literature there are few texts explaining how fascial stasis or altered movement of the various connective layers can generate a clinical problem. Certainly, the fascia plays a significant role in conveying mechanical tension, in order to control an inflammatory environment. The fascial continuum is essential for transmitting muscle force, for correct motor coordination, and for preserving the organs in their site; the fascia is a vital instrument that enables the individual to communicate and live independently. This article considers what the literature offers on symptoms related to the fascial system, trying to connect the existing information on the continuity of the connective tissue and symptoms that are not always clearly defined. In our opinion, knowing and understanding this complex system of fascial layers is essential for the clinician and other health practitioners in finding the best treatment strategy for the patient.

Keywords:

Introduction: definition of fascia

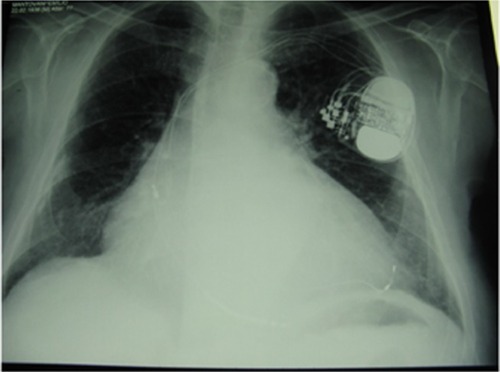

Every body structure is wrapped in connective tissue, or fascia, creating a structural continuity that gives form and function to every tissue and organ.Citation1–Citation6 The human body must be considered as a functional unit, where every area is in communication with another through the fascial continuum, consequently originating perfect tensegritive equilibrium.Citation5 Medical literature does not suggest a sole definition of fascia, because it varies in terms of thickness, function, composition, and direction depending on its location. The fascial tissue is equally distributed throughout the entire body, enveloping, interacting with, and permeating blood vessels, nerves, viscera, meninges, bones, and muscles, creating various layers at different depths, and forming a tridimensional metabolic and mechanical matrix.Citation6,Citation7 The fascia becomes an organ that can affect an individual’s health.Citation8 Awareness of its functions and of the areas it controls becomes significant within a more general perspective concerning the patient’s wellness and health ().

Figure 1 Shape and arrangement of the muscles on the ventral (A), dorsal (B), and lateral (C) surface of the human body.

From an embryological perspective, the fascial system originates in the mesoderm, although according to some authors this connective network can be partially found in the neural crests (ectoderm), with particular reference to the cranial and cervical area.Citation8–Citation10

The most external layer is denominated subcutaneous fascia or loose (areolar) connective fascia.Citation7,Citation11 This layer is made up of several levels, each with variable amounts of fibroblasts (ie, connective cells) arranged in a disorderly manner and soaked in a gelatinous substance known as extracellular matrix, where numerous molecules (ie, glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans and polysaccharides such as hyaluronic acid) can be found.Citation3,Citation12 This superficial layer is not located exclusively under the derma, but it permeates the entire body, enveloping the organs and forming the stroma, the neurovascular branches, and the different fascias of the muscle districts, finally resting on the deep fascia.Citation13–Citation15 The superficial fascia is made up of different layers, whose formation facilitates the sliding of one layer over another, as of the structures enveloped or in contact with the aforesaid fascia.Citation12–Citation15 The number of layers of the superficial fascia and the amount of substances they contain depend on the quantity of fat, the sex, and the body area concerned.Citation12,Citation13 The superficial fascia is rich in water, arranged in liquid crystals.Citation16 The various layers communicate by a microvacuolar system, which is in turn composed of the same structures of the superficial fascia; it is a microscopic web, concerning vessels and nerves, in varying directions, and is highly deformable.Citation11 According to some texts, within the superficial fascia there is a vascular network independent of the lymphatic and blood pathways. It is called the Bonghan duct system, and supposedly eases communication among all body areas.Citation17–Citation21 This system is composed of the same substance forming the superficial fascia.Citation9

The deep fascia is the last connective layer before coming in contact with the somatic structure (ie, bones and muscles), and the visceral and vascular systems. It is characterized by various levels of loose connective tissue.Citation3,Citation22 Its vascular and lymphatic system is well developed, with numerous corpuscles in charge of proprioception, particularly the Ruffini’s and Pacini’s corpuscles.Citation22 It is a less extendable fibrous layer, with collagen fibers arranged more regularly, thick and parallel to each other; it is rich in hyaluronic acid.Citation7,Citation22

According to some authors, the fascial layer enveloping the organs is a serous fascia, but in fact it is the prolongation of the deep fascia.Citation1,Citation23

All fascial layers contain a variable amount of fibroblasts with the ability to contract, known as myofibroblasts. They contain a type of actin similar to the one traceable in the muscles of the digestive system; ie, alpha-smooth muscle actin.Citation6 Scientific research has proven that the fascial continuum is innervated by the autonomic sympathetic system.Citation6

Symptoms: facts and hypotheses

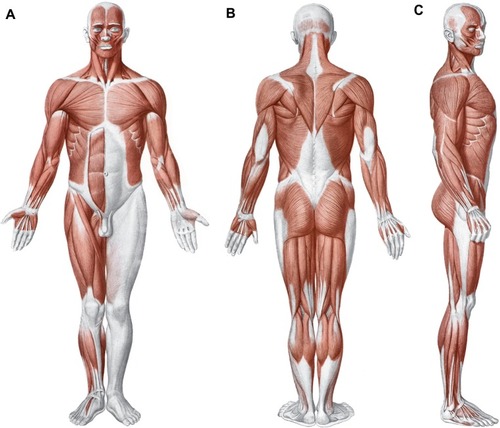

The fascial continuum is essential for transmitting the muscle force, for correct motor coordination, and for preserving the organs in their sites: the fascia is a vital instrument that enables the individual to communicate and live independently. The transmission of the force is ensured by the fascial integrity, which is expressed by the motor activity produced; the tension produced by the sarcomeres results in muscle activity, using the various layers of the contractile districts (epimysium, perimysium, endomysium), with different directions and speed ().Citation6,Citation11,Citation24,Citation25

Figure 2 Transverse section at the level of the upper third of the leg.

The connective tissue can control the orientation of the muscle fibers, so as to reflect the vector of the force’s direction, and to render the transition of the tension more fluid and ergonomic.Citation24 The fascial system is rich in proprioceptors, particularly the Ruffini’s and the Pacini’s corpuscles, mostly in the areas of transition between the articulation and the fascia, and between the fascia and the muscular tissue, blending with the receptors of these structures.Citation6,Citation8 The fascial continuum can be considered a sense organ of human mechanics, which affects daily postural patterns.Citation6,Citation8,Citation26

The muscle system is part of the fascial continuum, and when it is affected by pathologies or systemic disorders such as visceral, genetic, vascular, metabolic and alimentary disorders, its function undergoes a nonphysiological alteration; there are many epigenetic processes that can lead to its adjustment as a response to mechanotransductive stimuli, resulting in further decrease of its function and properties.Citation27–Citation37 Once altered, the fascial continuum generates a symptomatology that deteriorates the health condition of the patient, very often developing symptoms that are more significant than the clinical parameters diagnosed through medical diagnostic devices.Citation38–Citation41 Chronic fatigue, for instance, can be associated with the fascial system, particularly when the pathological disorder has persisted for several years.Citation42 Recent experimental studies have shown that common physiological mechanisms may be involved in the causation of muscle pain and fatigue; the nociceptive afferent inputs from the fascial system can modulate the afferent response from the central nervous system.Citation42 If the afferent is not physiological, the efferent will be in dysfunction and in pathology.Citation42

An increased level of circulating cytokines originating in the connective system, due to systemic pathologies, could develop neuropathic pain.Citation43–Citation46 The connective tissue can directly convey pain signals; in fact, it contains nociceptors that can translate mechanical stimuli into pain information. Furthermore, if there are nonphysiological mechanical stimuli, the proprioceptors can turn into nociceptors.Citation3,Citation6,Citation7 There are many reasons why the fascial continuum can turn into a source of pain. The nociceptors synthesize some neuropeptides that can alter the surrounding tissue, and generate an inflammatory environment; the epineurium and the perineurium, both belonging to the fascial system, are innervated by the nervi nervorum, which can develop pain sensation creating a vicious circle, when they are in contact with pro-inflammatory molecules.Citation6,Citation47 All the fascial layers need hyaluronic acid to slide over each other; if its quantity decreases or it is not regularly distributed, the local or systemic sliding property of the connective tissue is compromised.Citation12 There are some researchers who suggest strongly that any change in the viscoelasticity of the fascial system activates the nociceptors.Citation3,Citation12 The hyaluronic acid becomes adhesive and less lubricated, altering the lines of forces within the various fascial layers.Citation3 This mechanism could be one of the causes of articular stiffness and pain in the morning.Citation11 In fact, the stiffness experienced by some patients when they wake up in the morning could be related not with the joint but with the fascial system: if there is a minor quantity of hyaluronic acid or when it is not equally distributed, the tissue is dehydrated and has less possibility of sliding.Citation3,Citation11,Citation12 The same dehydration prevents the catabolites of cellular metabolism from being properly removed, stimulating the nociceptors; the accumulation of metabolites alters the pH inside the fascia, making a more acid cell environment; this results in dysfunctional physiology of the hyaluronic acid, and complicates the sliding of the different fascial layers, again stimulating the nociceptors.Citation3,Citation12

Reduced sliding of the various layers limits the functionality of the endocannabinoid system. There is a close relationship between the endocannabinoid or endorphin system and the fibroblasts. The cannabinoid receptor, or CB1, is mainly housed in the nervous system, but it can be found in the fascial system and in the fibroblasts as well, particularly near the neuromuscular junction.Citation48 This relationship is believed to better manage any inflammation and pain information originating in the fascial tissue, as the fascia undergoes continuous remodeling during the day.Citation48,Citation49

It is hypothesized that the axoplasmic flow originating in the dorsal ganglionic roots carries some molecules to the distal nerve endings, in an attempt to reduce pain information deriving from the nociceptors in the fascial continuum; if there is a mechanical barrier owing to a reduction of the fascial sliding, the axoplasmic flow will be hindered, with consequent onset of hyperalgia.Citation48 The nerve has the ability to adjust itself in case of length variations of the extremities and trunk, in order to preserve its functions; in case of difficulty in sliding of the different layers that are crossed by the nerve structure, there is a neural tension or neurodynamic dysfunction, developing sensations of pain.Citation3,Citation50 This is due to a reduction in the intraneural blood flow, and to the release of inflammatory neuropeptides.Citation50 According to some authors, the loss of a correct sliding of the layers is demonstrated by an increased density of the fascial thickness, which can be detected through ultrasonography, explaining atypical symptomatology of chronic pain; this phenomenon is not termed fibrosis but fascial densification.Citation3,Citation51

Defective sliding, for instance due to a scar, generates anomalous tension, which then affects the fascial continuum, developing painful symptoms.Citation1,Citation52 Tensional alterations can derive from the contractile property of fibroblasts, creating a fascial tonus that is independent of neurological intervention.Citation1,Citation52,Citation53 A nonphysiological mechanical environment stimulates an inflammatory environment, with resultant fibroblasts’ hyperplasia and further fascial densification, which then develops into chronic inflammation and into the sensitization of nociceptors.Citation10,Citation47,Citation54,Citation55 The inflammation experienced by fibroblasts increases the extracellular edema; this edema depends not only on an increased vascular permeability, but also on loose fascial tissue, which draws liquids inside.Citation52 The edema determines an increase in tension and stiffness, resulting in difficult sliding of the fascial layers and pain.Citation52 This scenario makes the fibroblast release adenosine triphosphate (ATP), stimulating the nociceptors.Citation52,Citation55 It is probable that the alteration of the physiological flow of fluids such as lymph and blood, caused by a tensional anomaly experienced by fibroblasts, is related to one of the causes of local and systemic pathologies, such as the formation of tumors.Citation52 The sensitization of nociceptors could derive from a local ischemia, caused by nonphysiological fascial tension, which hinders the skeletal muscle from functioning properly, for instance in trigger points.Citation56,Citation57 Pain receptors could be activated by inflammatory molecules, ATP and glutamate (an important neurostimulator), a decrease in pH, and other neuropeptides (such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide).Citation56 These alterations, which are mostly considered muscular alterations, can also be determined by visceral effects on the muscle tissues, proving the continuity of the fascial system.Citation57–Citation59

The fibroblasts (the foundations of the fascial system) affect the immune system, and as a consequence bone tissue; this phenomenon is called osteoimmunology.Citation47,Citation60 The immune system and bone tissue share molecular interactions, including transcription factors, signal molecules and membrane receptors; in particular, osteoclasts are sensitized by cytokines, and vice versa.Citation61 When the layers of the fascial continuum do not slide properly over one another, from the most superficial layer to the periosteum, an inflammatory environment develops, either acute or chronic; the resultant cytokines could activate the osteoclasts and bone resorption, generating osteoporosis in the long run.Citation7,Citation61 This is probably one of the causes producing articular disorders in rheumatoid arthritis.Citation47

Densification can develop into fibrosis. Fibrosis or fibromatosis results from a disorder of the connective tissue affected by hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the fibroblasts, due to a chronic inflammatory environment, nonphysiological mechanical stress and immobility; calcification phenomena can be observable as well.Citation47 These morphological and functional variations have been verified in elbow tendonitis and in plantar fasciitis.Citation47 The fibroblasts lose their physiological direction, which is determined by new pathological force vectors, revealing a chaotic organization.Citation47,Citation62 In the presence of a fibromatosis similar to the cicatricial tissue, for instance in Dupuytren’s contracture, there is an increase in the percentage of fibroblasts, which then change into myofibroblasts, with consequent altered tension experienced by the fascial continuum; the result is a vicious circle of inflammation and activation of the nociceptors.Citation62 The important event that must be underlined is that the connective tissue found next to an ailing fascial area undergoes nonphysiological mechanical stimuli, resulting in further functional deterioration of the fascial layers.Citation62 This mechanism, which alters the correct distribution of the tension generated and perceived, concerns the entire fascial continuum, and all the structures it surrounds and sustains.Citation63–Citation65

Clinical scenarios: facts and hypotheses

Research has proven that patients who suffer from chronic lumbar backache present an inflammation of the local fascial area, and experience degenerating variations of collagen fibers and microcalcifications, besides a 25% increase in thickening of the perimuscular fascial tissue if compared with nonsuffering subjects.Citation47 The entire thoracolumbar fascia plays a fundamental role in this pathological condition.Citation66 The absence of sliding of the different layers in the lumbar area and the morphological alteration of the tissue generate a nonphysiological mechanical tension, resulting in lumbar pain symptoms.Citation66 This nonphysiological condition develops a lack of coordination in the activation of the muscles of the thoracolumbar fascia involved, with resultant mechanical instability of the lumbar column and pain.Citation67 Pain symptoms are intensified by stress, as the fascia is innervated by the sympathetic nervous system, especially in the area near the blood vessels; therefore, it is likely to produce vasospasm and ischemic pain.Citation47,Citation68 This negatively affects posture and walking.Citation6,Citation66 From the current data in the literature, we can strongly assume that the connective tissue is more responsive than the muscular tissue in the activation of nociceptors, and examination on animals has proven that the medullar neurons receiving fascial nociceptive afferents are activated 4% to 15% more than a noninflamed fascia, with an experimentally-induced inflammation of a low back pain muscle (multifidus).Citation68–Citation70 The thoracolumbar fascia proceeds with the gluteus maximus and the lower extremity, involving the fascia of the thigh, the leg, and the plantar fascia of the foot, and is closely related to the pelvic floor.Citation65,Citation71–Citation77 We can logically hypothesize a problem of instability in the ankle caused by the anatomical connection with the thoracolumbar fascia, because of a proprioceptive alteration of the fascial continuum and of its relevant muscular coordination. An aching ankle has been proven to cause urogenital and visceral disorders, such as dyspareunia.Citation64 This event can be explained by the muscular connections existing between the pelvic floor and the ankle (rectum abdominis, adductor lungus and triceps surae), producing hypertonus of the pelvic musculature, and by nociceptive information, which at the medullar level can develop a metabolic and electrical antidromic communication, and involve a greater number of neurons of the metameric segment, consequently concerning the viscera (somaticovisceral reflex).Citation64,Citation65,Citation78 The fascial continuum can also develop symptoms in areas which are far from the original dysfunctional point, making it more difficult to diagnose the patient’s clinical scenario. For this reason, a patient must be observed as a sole entity and not as a collection of single body segments.Citation1,Citation65

In atypical cervicalgia an alteration in the thickness of the fascial layers has been verified, with consequent altered spinal mobility and pain.Citation3,Citation51,Citation79 This reduction of movement of the layers is called fascial stasis, because in this state the fascial fluids flow with difficulty. The cervical tract has a fundamental importance for correct occlusion and postural balance; its dysfunction alters mastication and balance.Citation80–Citation83 The muscles involved in mastication, with opening and closing of the jaw, are surrounded by the cervical fascia: suprahyoid, masseteric, pterygoid, lingual and temporal muscles.Citation84,Citation85 We can reasonably assert that a dental disorder can directly originate in the thickening of the cervical fascial layers; in this event, a therapy merely aimed at restoring the functionality of the occlusion will be ineffective, if the cervical area is not treated.

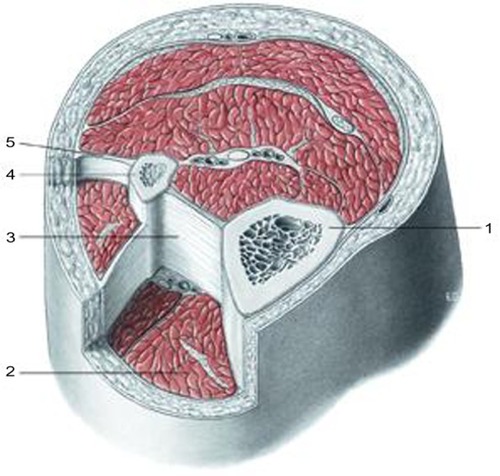

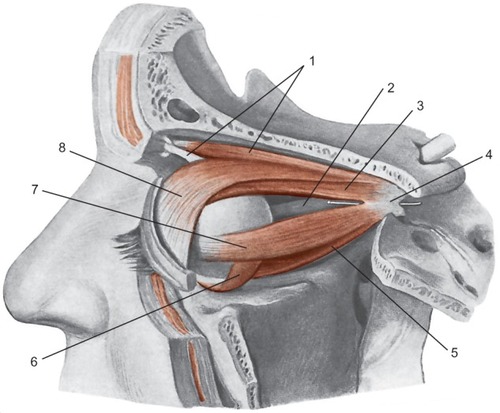

Cervical fascia and visual control are closely related. There is a variety of reflexes, such as the vestibulo-ocular reflex (ie, the eyes move as a result of vestibular information), the optokinetic reflex (they move in response to the stimulation of visual movement), and the cervico-ocular reflex, occurring when the head is turned, in order to stabilize the image on the retina while the head is moving.Citation86,Citation87 Any dysfunction in the cervical fascial area will be problematic for these reflexes.Citation86,Citation87 This is due to the lack of coordination of the muscular areas belonging to the cervical fascial layers, and the connection with the cranial fascia.Citation87 The posterior superficial cervical fascia (the continuation of the thoracolumbar fascia), which surrounds the nuchal line, merges with the superior lateral two-thirds of the occipitofrontalis muscle.Citation65,Citation88 The occipitofrontalis muscle runs from the condylar area of the occiput under the superficial cranial fascia, and then through an ample aponeurosis called Galea aponeurotica comes in contact with the frontal venter musculi, bridging the gap between the occipital bone and the frontal one.Citation88 The superficial fascia of the skull concerns the temporoparietal fascia, which then combines with the venter musculi of the frontal portion.Citation88 The occipitofrontalis muscle is connected with Muller’s muscle; ie, musculus levator palpebrae ().Citation88

Figure 3 Presentation of the mimic muscles of the head. These muscles occupy a superficial position.

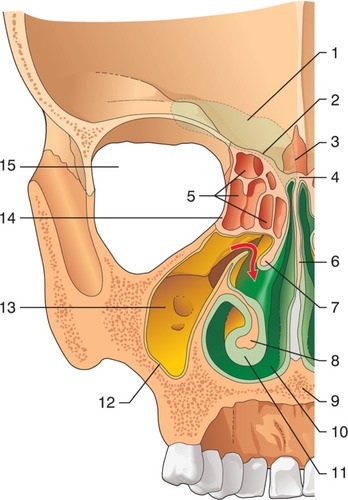

The connective tissue of Muller’s muscle is rich in mechanoreceptors, so as to induce a reflex contraction of the occipitofrontalis muscle, and to keep the eyes aligned for correct posture.Citation89 When there is hyperreflexia of the mechanoreceptors in Muller’s muscle, the contraction of the occipitofrontalis muscle is hyperstimulated, with resultant chronic tension in the cervical area and headache.Citation90 The more the eyelid is lowered, the greater the extension of the high cervical tract is needed, in order to keep a good visual field, with involuntary involvement of the muscular connective system, generating further hypertonia.Citation88 The occipitofrontalis muscle is significant from an ontological perspective as well as for a child’s growth, because its tension is fundamental for correct development and regular morphology of the skull, and again it is essential for its influence on the spheno-occipital synchondrosis during the growth, and to facilitate the development of a good phonatory system.Citation91 Muller’s muscle is connected with Tenon’s capsule, where the eyeball is located; particularly, they share extraocular muscles; Tenon’s capsule surrounds the optical nerve where it terminates in the eye, blending with the meningeal tissue.Citation92,Citation93 We can theorize that a tension in the fascial area of the high cervical tract will affect the movement of the eyeball, altering the visual field and posture, or causing dysfunction related to the fascial traction on the optical nerve, with resultant alteration in the ocular reflexes. Further studies are needed. The functional and tensional integrity of the fascial continuum plays a major role in the nonpathological homeostasis, and guarantees the patient a satisfactory quality of life in terms of socialization and independence ().

Figure 4 Diagram showing the elevator muscle of the upper eyelid and extrinsic muscle of the eyeball, after lifting the cranial vault and the lateral wall of the orbit.

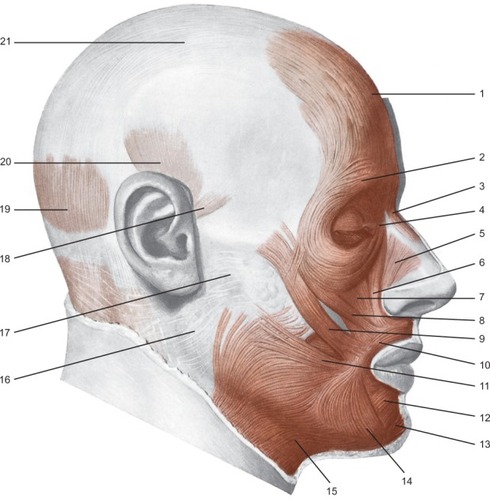

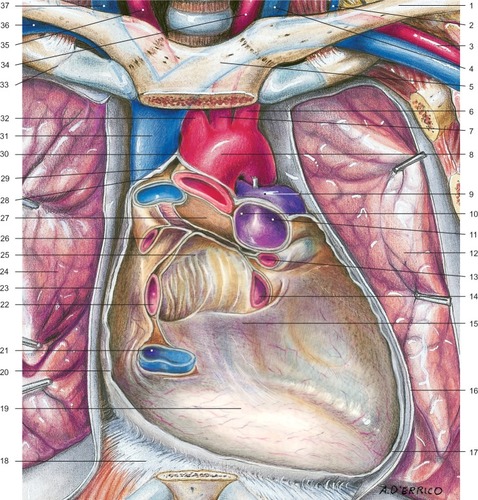

The vascular tree is surrounded by the connective system, and its continuity enables the myocardium to affect all the areas permeated by blood with its systole and diastole.Citation7,Citation94 The heart itself is surrounded by a tridimensional system of connective tissue, which connects it to the lungs and to the endothoracic fascia ().Citation65,Citation95–Citation97

Figure 5 Aspect of the pericardium after resection and removal of its anterior wall, the great vessels, and heart.

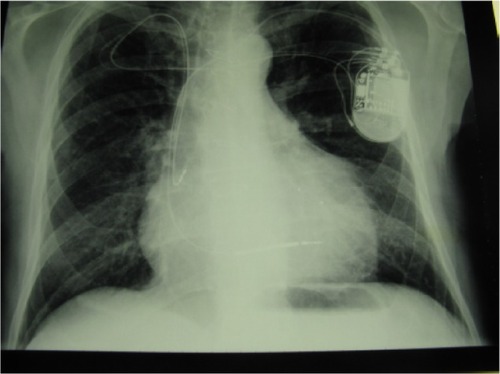

The latter is the continuation of the cervical fasciae, which enter the extracranial and intracranial fasciae through the dural leaflets.Citation65 The cardiovascular tree embriologically originates in the ectoderm and mesoderm, as does the fascial continuum.Citation8–Citation10,Citation98,Citation99 The pathway of the nervous system, whether it is central or peripheral, concerns the fascial continuum.Citation7,Citation13–Citation15 This close connection explains the cerebral motility caused by cardiovascular pulsatility; the cerebral oscillatory activity is synchronized with the systole and diastole of the heart.Citation100 This activity concerns the entire spinal axis, and involves a caudal thrust to the cerebellar foramen magnum, during the systole, and a cranial reflex, during the diastole.Citation100 The aforementioned cerebral oscillation is perceived by osteopaths through cranial movement.Citation100,Citation101 Recent research has proven that human touch can distinguish extremely light objects or slight vibrations. In static palpation, the range of discrimination in case of vibrations reaches 0.2 mm, whereas discrimination while touching a moving surface is measured in microns.Citation102 Cerebral oscillations affect the production of cerebrospinal fluid or liquor.Citation100 Recent studies have demonstrated that the liquor is mostly drained by the lymphatic system, flowing from the perineural and perivascular sheaths to the lymphatic vessels; when it is in the lymphatic system, the liquor flows to the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, and then to the epithelium and the nasal mucosa ().Citation103,Citation104

Figure 6 Schematic representation of the front section of the nasal cavity viewed from the rear face.

From here, a system of vessels and lymphatic nodes carry the liquor to the buccal floor and the neck, finally involving the venous system.Citation105–Citation107 When the heart suffers from rhythm alteration, patients are treated with drugs to regulate the rhythm and arrhythmia, or they are surgically treated, for instance with ablations, or with temporary/permanent placement of pacemakers and defibrillators (implantable cardiac defibrillators) ().Citation108–Citation110

We can hypothesize that pharmacological or surgical treatment that regulates cardiac frequency, as well as the pathological alteration of the rhythm, alters the production of the cerebrospinal liquor, and as a consequence negatively affects the environment of nasal mucosa, resulting in rhinitis or sinusitis. An imbalance in the quantity of liquor can alter the immunological environment, whether cerebral or systemic, as it transports many substances (ie, electrolytes, catabolites, hormones and neuropeptides).Citation100,Citation104,Citation107 Altered homeostasis of the nasal mucosa and of the olfactory nerve can develop disorders in the superior respiratory tract, which can convey germs to the cerebral area, through the lymphatic pathways departing from the brain.Citation104

A lesion in the phrenic or vagal nerve results in dysfunction of the contractile activity of the diaphragmatic muscle.Citation65 The respiratory diaphragm and the nerves that electrically activate the muscle belong to the fascial continuum, which merges with the intracranial meningeal tissue, passing through the endothoracic, thoracolumbar and cervical fascia, and involving the viscera in the thoracic cage.Citation65,Citation111,Citation112 Respiration, particularly forced respiration, has been proven to affect cerebral motility and the synthesis of cerebrospinal liquor.Citation100 Forced expiration generates a caudal movement of the brain, whereas forced inspiration causes the cephalic drainage.Citation100 We can theorize that if the diaphragmatic muscle does not have a regular contraction, it negatively affects the production of liquor, endangering one’s health ().

Figure 8 Pacemaker biventricular-bicameral/implantable cardiac defibrillator.

The same vasomotor activity of blood and lymphatic vessels that is controlled by the autonomous system can affect the synthesis of liquor, although less importantly and independently of the cardiac and respiratory rhythm.Citation100 Again, we can assume that a dysfunction of the sympathetic system, resulting from chronic nociceptive information of the fascial continuum (for instance, due to a cicatricial adhesion), alters the synthesis of cerebrospinal liquid, with consequent reduction of systemic homeostasis.Citation1

Conclusion

Currently, there is still little information on the functions and interactions between the fascial continuum and the body system; unfortunately, in medical literature there are few texts explaining how fascial stasis or altered movement of the various connective layers can generate a clinical problem. Certainly, the fascia plays a significant role in conveying mechanical tension, in order to control an inflammatory environment. The fascia is the philosophy of the body, meaning that each body region is connected to another, whereas osteopathy is the philosophy of medicine, meaning that the entire human body must work in harmony. Knowing and understanding this complex system of fascial layers is essential for the clinician, and all health practitioners, in finding the best treatment strategy for the patient.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Fabiola Marelli, the Director of CRESO, Osteopathic Centre for Research and Studies, for her friendship and support.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BordoniBZanierESkin, fascias, and scars: symptoms and systemic connectionsJ Multidiscip Healthc20137112424403836

- AbbottRDKoptiuchCIatridisJCHoweAKBadgerGJLangevinHMStress and matrix-responsive cytoskeletal remodeling in fibroblastsJ Cell Physiol20132281505722552950

- SteccoAGesiMSteccoCSternRFascial components of the myofascial pain syndromeCurr Pain Headache Rep201317835223801005

- BuckleyCDWhy does chronic inflammation persist: An unexpected role for fibroblastsImmunol Lett20111381121421333681

- BordoniBZanierECranial nerves XIII and XIV: nerves in the shadowsJ Multidiscip Healthc20136879123516138

- TozziPSelected fascial aspects of osteopathic practiceJ Bodyw Mov Ther201216450351923036882

- FindleyTWShalwalaMFascia Research Congress evidence from the 100 year perspective of Andrew Taylor StillJ Bodyw Mov Ther201317335636423768282

- van der WalJThe architecture of the connective tissue in the musculoskeletal system-an often overlooked functional parameter as to proprioception in the locomotor apparatusInt J Ther Massage Bodywork20092492321589740

- BaiYYuanLSohKSPossible applications for fascial anatomy and fasciaology in traditional Chinese medicineJ Acupunct Meridian Stud20103212513220633527

- BuckleyCDPillingDLordJMAkbarANScheel-ToellnerDSalmonMFibroblasts regulate the switch from acute resolving to chronic persistent inflammationTrends Immunol200122419920411274925

- GuimberteauJCDelageJPMcGroutherDAWongJKThe microvacuolar system: how connective tissue sliding worksJ Hand Surg Eur Vol201035861462220571142

- SteccoCSternRPorzionatoAHyaluronan within fascia in the etiology of myofascial painSurg Radiol Anat2011331089189621964857

- Abu-HijlehMFRoshierALAl-ShboulQDharapASHarrisPFThe membranous layer of superficial fascia: evidence for its widespread distribution in the bodySurg Radiol Anat200628660661917061033

- LangevinHMCornbrooksCJTaatjesDJFibroblasts form a body-wide cellular networkHistochem Cell Biol2004122171515221410

- LangevinHMBouffardNAFoxJRFibroblast cytoskeletal remodeling contributes to connective tissue tensionJ Cell Physiol201122651166117520945345

- PollackGHThe Fourth Phase of Water: a role in fascia?J Bodyw Mov Ther201317451051124139011

- LiHYChenMYangJFFluid flow along venous adventitia in rabbits: is it a potential drainage system complementary to vascular circulations?PLoS One201277e4139522848483

- LeeBCYoonJWParkSHYoonSZToward a theory of the primo vascular system: a hypothetical circulatory system at the subcellular levelEvid Based Complement Alternat Med2013201396195723853665

- LiHYYangJFChenMVisualized regional hypodermic migration channels of interstitial fluid in human beings: are these ancient meridians?J Altern Complement Med200814662162818684070

- ParkESKimHYYounDHThe primo vascular structures alongside nervous system: its discovery and functional limitationEvid Based Complement Alternat Med2013201353835023606882

- SohKSBonghan circulatory system as an extension of acupuncture meridiansJ Acupunct Meridian Stud2009229310620633480

- SteccoCTiengoCSteccoAFascia redefined: anatomical features and technical relevance in fascial flap surgerySurg Radiol Anat201335536937623266871

- LeeSJooKBSongSYAccurate definition of superficial and deep fasciaRadiology20112613994 author reply 994–995; author reply 99522095999

- TurrinaAMartínez-GonzálezMASteccoCThe muscular force transmission system: role of the intramuscular connective tissueJ Bodyw Mov Ther20131719510223294690

- PurslowPPMuscle fascia and force transmissionJ Bodyw Mov Ther201014441141720850050

- SteccoCGageyOBelloniAAnatomy of the deep fascia of the upper limb. Second part: study of innervationMorphologie200791292384317574469

- AuthierFJChariotPGherardiRKSkeletal muscle involvement in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)Muscle Nerve200532324726015902690

- McLoughlinDMSpargoEWassifWSStructural and functional changes in skeletal muscle in anorexia nervosaActa Neuropathol19989566326409650756

- OlssonAHRönnTElgzyriTThe expression of myosin heavy chain (MHC) genes in human skeletal muscle is related to metabolic characteristics involved in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetesMol Genet Metab2011103327528121470888

- Urbano-MárquezAFernández-SolàJEffects of alcohol on skeletal and cardiac muscleMuscle Nerve200430668970715490485

- DiffeeGMKalfasKAl-MajidSMcCarthyDOAltered expression of skeletal muscle myosin isoforms in cancer cachexiaAm J Physiol Cell Physiol20022835C1376C138212372798

- SakkasGKBallDMercerTHSargeantAJTolfreyKNaishPFAtrophy of non-locomotor muscle in patients with end-stage renal failureNephrol Dial Transplant200318102074208113679483

- CouillardAPrefautCFrom muscle disuse to myopathy in COPD: potential contribution of oxidative stressEur Respir J200526470371916204604

- VescovoGSerafiniFFacchinLSpecific changes in skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain composition in cardiac failure: differences compared with disuse atrophy as assessed on microbiopsies by high resolution electrophoresisHeart19967643373438983681

- ToffolaEDSparpaglioneDPistorioABuonocoreMMyoelectric manifestations of muscle changes in stroke patientsArch Phys Med Rehabil200182566166511346844

- CiciliotSRossiACDyarKABlaauwBSchiaffinoSMuscle type and fiber type specificity in muscle wastingInt J Biochem Cell Biol201345102191219923702032

- BernardiPBonaldoPMitochondrial dysfunction and defective autophagy in the pathogenesis of collagen VI muscular dystrophiesCold Spring Harb Perspect Biol201355a01138723580791

- GiacomelliILSteidleLJMoreiraFFMeyerIVSouzaRGPincelliMPHospitalized patients with COPD: analysis of prior treatmentJ Bras Pneumol201440322923725029645

- StendardiLGrazziniMGigliottiFLottiPScanoGDyspnea and leg effort during exerciseRespir Med200599893394215950133

- SavagePAShawAOMillerMSEffect of resistance training on physical disability in chronic heart failureMed Sci Sports Exerc20114381379138621233772

- ErbsSHöllriegelRLinkeAExercise training in patients with advanced chronic heart failure (NYHA IIIb) promotes restoration of peripheral vasomotor function, induction of endogenous regeneration, and improvement of left ventricular functionCirc Heart Fail20103448649420430934

- MastagliaFLThe relationship between muscle pain and fatigueNeuromuscul Disord201222Suppl 3S178S18023182635

- ClarkAKOldEAMalcangioMNeuropathic pain and cytokines: current perspectivesJ Pain Res2013680381424294006

- GanWQManSFSenthilselvanASinDDAssociation between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysisThorax200459757458015223864

- DixonDLGriggsKMBerstenADDe PasqualeCGSystemic inflammation and cell activation reflects morbidity in chronic heart failureCytokine201156359359921924921

- DuncanBBSchmidtMIPankowJSAtherosclerosis Risk in Communities StudyLow-grade systemic inflammation and the development of type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities studyDiabetes20035271799180512829649

- LiptanGLFascia: A missing link in our understanding of the pathology of fibromyalgiaJ Bodyw Mov Ther201014131220006283

- McPartlandJMExpression of the endocannabinoid system in fibroblasts and myofascial tissuesJ Bodyw Mov Ther200812216918219083670

- HicksMRCaoTVCampbellDHStandleyPRMechanical strain applied to human fibroblasts differentially regulates skeletal myoblast differentiationJ Appl Physiol (1985)2012113346547222678963

- RowePCFontaineKRViolandRLNeuromuscular strain as a contributor to cognitive and other symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome: hypothesis and conceptual modelFront Physiol2013411523720638

- SteccoAMeneghiniASternRSteccoCImamuraMUltrasonography in myofascial neck pain: randomized clinical trial for diagnosis and follow-upSurg Radiol Anat201436324325323975091

- LangevinHMNedergaardMHoweAKCellular control of connective tissue matrix tensionJ Cell Biochem201311481714171923444198

- EaganTSMeltzerKRStandleyPRImportance of strain direction in regulating human fibroblast proliferation and cytokine secretion: a useful in vitro model for soft tissue injury and manual medicine treatmentsJ Manipulative Physiol Ther200730858459217996550

- CaoTVHicksMRCampbellDStandleyPRDosed myofascial release in three-dimensional bioengineered tendons: effects on human fibroblast hyperplasia, hypertrophy, and cytokine secretionJ Manipulative Physiol Ther201336851352124047879

- DeisingSWeinkaufBBlunkJObrejaOSchmelzMRukwiedRNGF-evoked sensitization of muscle fascia nociceptors in humansPain201215381673167922703891

- ShahJPGilliamsEAUncovering the biochemical milieu of myofascial trigger points using in vivo microdialysis: an application of muscle pain concepts to myofascial pain syndromeJ Bodyw Mov Ther200812437138419083696

- Fernández-de-las-PeñasCDommerholtJMyofascial trigger points: peripheral or central phenomenon?Curr Rheumatol Rep201416139524264721

- MuscolinoJEAbdominal wall trigger point case studyJ Bodyw Mov Ther201317215115623561860

- LangevinHMConnective tissue: a body-wide signaling network?Med Hypotheses20066661074107716483726

- MoriGD’AmelioPFaccioRBrunettiGThe Interplay between the bone and the immune systemClin Dev Immunol2013201372050423935650

- NakashimaTTakayanagiHOsteoimmunology: crosstalk between the immune and bone systemsJ Clin Immunol200929555556719585227

- ViLFengLZhuRDPeriostin differentially induces proliferation, contraction and apoptosis of primary Dupuytren’s disease and adjacent palmar fascia cellsExp Cell Res2009315203574358619619531

- NorrisRADamonBMironovVPeriostin regulates collagen fibrillogenesis and the biomechanical properties of connective tissuesJ Cell Biochem2007101369571117226767

- KotarinosRMyofascial pelvic painCurr Pain Headache Rep201216543343822648177

- BordoniBZanierEAnatomic connections of the diaphragm: influence of respiration on the body systemJ Multidiscip Healthc2013628129123940419

- LangevinHMFoxJRKoptiuchCReduced thoracolumbar fascia shear strain in human chronic low back painBMC Musculoskelet Disord20111220321929806

- WillardFHVleemingASchuenkeMDDanneelsLSchleipRThe thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerationsJ Anat2012221650753622630613

- TesarzJHoheiselUWiedenhöferBMenseSSensory innervation of the thoracolumbar fascia in rats and humansNeuroscience201119430230821839150

- HoheiselUTaguchiTTreedeRDMenseSNociceptive input from the rat thoracolumbar fascia to lumbar dorsal horn neuronesEur J Pain201115881081521330175

- SchilderAHoheiselUMagerlWBenrathJKleinTTreedeRDSensory findings after stimulation of the thoracolumbar fascia with hypertonic saline suggest its contribution to low back painPain2014155222223124076047

- CarvalhaisVOOcarino JdeMAraújoVLSouzaTRSilvaPLFonsecaSTMyofascial force transmission between the latissimus dorsi and gluteus maximus muscles: an in vivo experimentJ Biomech20134651003100723394717

- BarkerPJHapuarachchiKSRossJASambaiewERangerTABriggsCAAnatomy and biomechanics of gluteus maximus and the thoracolumbar fascia at the sacroiliac jointClin Anat201427223424023959791

- HuangBKCamposJCMichael PeschkaPGInjury of the gluteal aponeurotic fascia and proximal iliotibial band: anatomy, pathologic conditions, and MR imagingRadiographics20133351437145224025934

- SteccoCPavanPPacheraPDe CaroRNataliAInvestigation of the mechanical properties of the human crural fascia and their possible clinical implicationsSurg Radiol Anat2014361253223793789

- PedrelliASteccoCDayJATreating patellar tendinopathy with Fascial ManipulationJ Bodyw Mov Ther2009131738019118795

- SteccoCCorradinMMacchiVPlantar fascia anatomy and its relationship with Achilles tendon and paratenonJ Anat2013223666567624028383

- SteccoAAntonioSGilliarWThe anatomical and functional relation between gluteus maximus and fascia lataJ Bodyw Mov Ther201317451251724139012

- LiSKukulkaCGRogersMWBruntDBishopMSural nerve evoked responses in human hip and ankle muscles while standingNeurosci Lett20043642596215196677

- TozziPBongiornoDVitturiniCFascial release effects on patients with non-specific cervical or lumbar painJ Bodyw Mov Ther201115440541621943614

- El HageYPolittiFHerpichCMEffect of facial massage on static balance in individuals with temporomandibular disorder – a pilot studyInt J Ther Massage Bodywork20136461124298296

- OhlendorfDRiegelMLin ChungTKoppSThe significance of lower jaw position in relation to postural stability. Comparison of a premanufactured occlusal splint with the Dental Power SplintMinerva Stomatol20136211–1240941724270202

- SforzaCTartagliaGMSolimeneUMorgunVKaspranskiyRRFerrarioVFOcclusion, sternocleidomastoid muscle activity, and body sway: a pilot study in male astronautsCranio2006241434916541845

- OtadiKHadianMRTalebianSShadmehrAEmamdoostSShahriarGThe effect of myofascial neck pain on postural control: visual deprivationJ Back Musculoskelet Rehabil201326437538023948823

- GuideraAKDawesPJFongAStringerMDHead and neck fascia and compartments: No space for spacesHead Neck20143671058106823913739

- WarshafskyDGoldenbergDKanekarSGImaging anatomy of deep neck spacesOtolaryngol Clin North Am20124561203122123153745

- KeldersWPKleinrensinkGJvan der GeestJNFeenstraLde ZeeuwCIFrensMACompensatory increase of the cervico-ocular reflex with age in healthy humansJ Physiol2003553Pt 131131712949226

- BexanderCSHodgesPWCervico-ocular coordination during neck rotation is distorted in people with whiplash-associated disordersExp Brain Res20122171677722179527

- KushimaHMatsuoKYuzurihaSKitazawaTMoriizumiTThe occipitofrontalis muscle is composed of two physiologically and anatomically different muscles separately affecting the positions of the eyebrow and hairlineBr J Plast Surg200558568168715927153

- MatsuoKOsadaYBanRElectrical stimulation to the trigeminal proprioceptive fibres that innervate the mechanoreceptors in Müller’s muscle induces involuntary reflex contraction of the frontalis musclesJ Plast Surg Hand Surg2013471142023210500

- MatsuoKBanRSurgical desensitisation of the mechanoreceptors in Müller’s muscle relieves chronic tension-type headache caused by tonic reflexive contraction of the occipitofrontalis muscle in patients with aponeurotic blepharoptosisJ Plast Surg Hand Surg2013471212923210499

- StanderwickRGRobertsWEThe aponeurotic tension model of craniofacial growth in manOpen Dent J2009310011319572022

- KakizakiHTakahashiYNakanoTAnatomy of Tenons capsuleClin Experiment Ophthalmol201240661161622172019

- KakizakiHTakahashiYNakanoTMüller’s muscle: a component of the peribulbar smooth muscle networkOphthalmology2010117112229223220591489

- TsamisAKrawiecJTVorpDAElastin and collagen fibre microstructure of the human aorta in ageing and disease: a reviewJ R Soc Interface201310832012100423536538

- BurlewBSWeberKTConnective tissue and the heart. Functional significance and regulatory mechanismsCardiol Clin200018343544210986582

- RabinowitzJGCohenBAMendlesonDSSymposium on Nonpulmonary Aspects in Chest Radiology. The pulmonary ligamentRadiol Clin North Am19842236596726382426

- NappiGTrittoFPFalcoALongobardiFCotrufoMNew surgical technique for harvesting the internal mammary arteryTex Heart Inst J19942121341377914766

- KodoKYamagishiHA decade of advances in the molecular embryology and genetics underlying congenital heart defectsCirc J201175102296230421914956

- SantoroMMPesceGStainierDYCharacterization of vascular mural cells during zebrafish developmentMech Dev20091268–963864919539756

- WhedonJMGlasseyDCerebrospinal fluid stasis and its clinical significanceAltern Ther Health Med2009153546019472865

- GardGAn investigation into the regulation of intra-cranial pressure and its influence upon the surrounding cranial bonesJ Bodyw Mov Ther200913324625419524849

- SkedungLArvidssonMChungJYStaffordCMBerglundBRutlandMWFeeling small: exploring the tactile perception limitsSci Rep20133261724030568

- BulatMKlaricaMRecent insights into a new hydrodynamics of the cerebrospinal fluidBrain Res Rev20116529911220817024

- GayFBacterial toxins and multiple sclerosisJ Neurol Sci20072621–210511217707408

- JohnstonMZakharovAPapaiconomouCSalmasiGArmstrongDEvidence of connections between cerebrospinal fluid and nasal lymphatic vessels in humans, non-human primates and other mammalian speciesCerebrospinal Fluid Res200411215679948

- PanWRle RouxCMLevySMBriggsCAThe morphology of the human lymphatic vessels in the head and neckClin Anat201023665466120533512

- SakkaLCollGChazalJAnatomy and physiology of cerebrospinal fluidEur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis2011128630931622100360

- ZhongLGaoYXiaHLiXWeiSPercutaneous coronary intervention delays pacemaker implantation in coronary artery disease patients with established bradyarrhythmiasExp Clin Cardiol2013181172124294031

- Health Quality OntarioImplantable cardioverter defibrillators. Prophylactic use: an evidence-based analysisOnt Health Technol Assess Ser2005514174

- GiambertiAChessaMAbellaRSurgical treatment of arrhythmias in adults with congenital heart defectsInt J Cardiol20081291374117689722

- GervasioAMujahedIBiasioAAlessiSUltrasound anatomy of the neck: The infrahyoid regionJ Ultrasound2010133858923396844

- MiyakeNTakeuchiHChoBHMurakamiGFujimiyaMKitanoHFetal anatomy of the lower cervical and upper thoracic fasciae with special reference to the prevertebral fascial structures including the suprapleural membraneClin Anat201124560761821647961

- AnastasiAA VV, Anatomia dell’uomo4th edEdi.ermes, MilanoHuman Anatomy Available from: http://www.eenet.itAccessed September 9, 2014