Abstract

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a neuropathic pain condition affecting the face. It has a significant impact on the quality of life and physical function of patients. Evidence suggests that the likely etiology is vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve leading to focal demyelination and aberrant neural discharge. Secondary causes such as multiple sclerosis or brain tumors can also produce symptomatic TN. Treatment must be individualized to each patient. Carbamazepine remains the drug of choice in the first-line treatment of TN. Minimally invasive interventional pain therapies and surgery are possible options when drug therapy fails. Younger patients may benefit from microvascular decompression. Elderly patients with poor surgical risk may be more suitable for percutaneous trigeminal nerve rhizolysis. The technique of radiofrequency rhizolysis of the trigeminal nerve is described in detail in this review.

Introduction

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a painful condition involving the face. It is the most frequently diagnosed form of facial pain with a prevalence of 4 per 100,000 in the general population.Citation1 It commonly affects patients aged over 50 years and occurs more frequently in women than men with a ratio of 1.5:1 to 2:1, respectively.Citation1 It is also more common in patients with multiple sclerosis (incidence of 1%–2%) and hypertension.Citation1 TN is associated with decreased quality of life and impairment of daily function. It impacts upon employment in 34% of patients, and depressive symptoms are not uncommon.Citation2,Citation3 The condition may be severely disabling with high morbidity, particularly in the elderly.Citation4

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of TN remains unclear. Evidence suggests that pain occurs because of pressure on the trigeminal nerve root at the entry zone into the pontine region of the brain stem.Citation4,Citation5 Compression by tumor or blood vessel may cause local pressure, leading to demyelination of the trigeminal nerve. Results from experimental studies suggest that demyelinated axons are prone to ectopic action potential generation.Citation4,Citation6 Demyelination has also been shown in cases of TN associated with multiple sclerosis and tumor compression of the trigeminal nerve root.

Diagnosis

TN is characterized by sharp, shooting, ‘electric shock-like’ pain sensation that is limited to one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve. It is almost always unilateral with the maxillary branch being most commonly affected and the ophthalmic branch the least.Citation1 Pain usually lasts from a few seconds to 2 min and may recur spontaneously between pain-free intervals. Most patients report a sensitive trigger zone that reproduces an attack of neuralgia if lightly touched. Routine daily activities that contact, mobilize, stretch, or even slightly stimulate the trigger zone, such as brushing the teeth, applying facial cosmetics, encountering a breeze, talking, or eating, may trigger intolerable pain.

The International Headache Society has published criteria for the diagnosis of classical or symptomatic TN ().Citation7 In classical TN, no etiology can be identified other than vascular compression. On the other hand, symptomatic TN is related to an underlying cause such as tumor compression or multiple sclerosis. It is therefore important to distinguish between the two as the focus in management of symptomatic TN is to treat the underlying cause.

Table 1 International Headache Society diagnostic criteria for trigeminal neuralgia

Another useful classification that is commonly used may be more relevant to clinicians:Citation8,Citation9

TN1 – idiopathic, spontaneous facial pain that is pre-dominantly episodic;

TN2 – idiopathic, spontaneous facial pain that is pre-dominantly constant;

Trigeminal neuropathic pain resulting from unintentional injury to the trigeminal nerve due to trauma or surgery;

Trigeminal deafferentation pain resulting from intentional injury to the nerve by peripheral nerve ablation, gangliolysis, or rhizotomy in an attempt to treat either TN or other related facial pain;

Symptomatic TN due to multiple sclerosis;

Post-herpetic TN following a cutaneous herpes zoster outbreak in the trigeminal distribution; and

Atypical facial pain that refers to facial pain secondary to a somatoform pain disorder and requires psychological testing for diagnostic confirmation.

Many TN patients may also manifest a combination of TN1 and TN2 characteristics, together or at separate times during the natural course of the disease. For example, a patient may have a dull, nearly constant background pain in between paroxysmal attacks of sharp or electrical shock-like pain.

Neurological examination is usually normal in patients with idiopathic TN, although a subtle trigeminal sensory deficit may be detected occasionally.Citation10 However, symptoms of TN may also be the first manifestation in patients with cerebellopontine angle tumors or multiple sclerosis. Therefore, patients should be asked about other neurologic symptoms such as tingling, numbness, loss of balance, weakness in one or more limbs, blurred or double vision, hearing loss, dizziness, headaches, and fits.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain is useful to exclude symptomatic TN due to multiple sclerosis and tumors. MRI sequences augmented by a three-dimensional gradient echo sequence such as fast inflow with steady-state precession or intravenous gadolinium–DTPA can also improve visualization of the vascular compression around the trigeminal nerve root.Citation11

Differential diagnoses for facial pain include headache disorders, temporomandibular joint pain, dental pain, chronic sinusitis, otitis media, as well as myofascial pain. A discussion of these conditions is beyond the scope of this review. In general, the facial location, sharp or electrical quality, excruciating intensity, phasic temporal profile, and responsiveness to a specific drug can help us distinguish TN from other types of facial pain.Citation10

Treatment

The treatment of patients with idiopathic TN is often a challenge in clinical practice, and conservative management with drug therapy is always the first-line treatment. When drugs are not efficacious or produce intolerable adverse effects, interventional pain treatment or surgery is the possible option.

Pharmacological treatment

Carbamazepine has been used for many decades in the treatment of TN, and it is the drug of choice.Citation12,Citation13 Meta-analyses have demonstrated the efficacy of carbamazepine with a number-needed-to-treat of 2.5.Citation13,Citation14 Carbamazepine may even have diagnostic utility because patients with classical TN will respond well to it. Patients with symptomatic TN or other causes of facial pain are less likely to respond to carbamazepine. Doses of carbamazepine range between 200 and 1200 mg daily.

Other medications with reported efficacy in TN include oxcarbazepine, baclofen, and lamotrigine.Citation15–Citation17 Other medications such as topiramate, gabapentin, pregabalin, and levetiracetam have shown success in treating TN, but evidence is limited to small uncontrolled studies or case reports.Citation15 Patients should receive an adequate trial of at least three drugs including carbamazepine before surgical or interventional treatment is considered.Citation10

Surgical treatment

Microvascular decompression (MVD) and gamma knife surgery (GKS) are surgical options available to patients with TN.

Surgical MVD

MVD has been widely used based on the theory that vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve is responsible for TN.Citation18,Citation19 Craniotomy is performed to separate the blood vessels from the trigeminal nerve using an inert sponge or felt.Citation20 A recent retrospective review of patients with TN who had undergone MVD showed that a high proportion of patients (71%) reported complete pain relief 10 years after surgery.Citation21

Mortality rate for MVD ranges from 0.2% to 0.5%. There is a 4% incidence of postoperative morbidity such as cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) leak, infarct, or hematoma formation.Citation21

Ablative techniques

Gamma knife surgery

GKS is a noninvasive stereotactic radiosurgical technique that utilizes a focused beam of radiation to target the root of the trigeminal nerve. It is commonly performed with the patient under sedation. Pain relief obtained from GKS is delayed and usually occurs about 2 weeks later. Initial good pain relief can be achieved in ~80% of patients.Citation22,Citation23 However, there is a risk of recurrence after 1 year.Citation22 GKS may be preferred to MVD in elderly patients because of the lower rate of surgical complications.Citation24 Complications include facial paresthesia, hypoesthesia, and sensory loss. Anesthesia dolorosa has not been reported.Citation15

Minimally invasive percutaneous techniques for treating TN include balloon compression, glycerol rhizolysis, and radiofrequency (RF) rhizotomy.

Balloon compression

In balloon compression, a small balloon is introduced percutaneously using a needle to compress the trigeminal ganglion. Pain relief was immediate in more than 80% of patients.Citation25,Citation26 Complications include severe bradycardia or asystole, corneal anesthesia, facial sensory loss or dysesthesia, and masseter weakness.Citation25 In a 20-year follow-up review, recurrence of pain occurred in 32% of patients over the entire study period.Citation26

Glycerol rhizolysis

This procedure is performed with the patient in the sitting position with the head flexed. A needle is introduced into the trigeminal cistern and glycerol is injected. As glycerol is hyperbaric, it will sink and produce discrete neurolytic lesions of the second and third divisions of the trigeminal nerve. Pain relief has been reported to be more than 90% in one study with a recurrence rate of 23% after a mean period of 30 months.Citation27

Radiofrequency rhizotomy

This review will focus on the role of RF rhizotomy in the treatment of TN. Patients with TN who have good to excellent pain relief with a diagnostic trigeminal ganglion block may be suitable candidates for percutaneous RF rhizotomy, especially if the pain relief is of a short duration. It is performed by destruction of the trigeminal ganglion or roots using RF.

RF is the most common percutaneous procedure used to treat TN, especially in elderly patients.

Procedure

Patients are fasted for at least 6 h before the procedure. Prophylactic antibiotic is administered 1 h before the procedure. Intravenous access is obtained, and standard monitors including electrocardiogram, blood pressure monitoring, and pulse oximetry are applied. Sedation is usually necessary to increase patient comfort and reduce anxiety.

The procedure is performed under fluoroscopic guidance with the patient in the supine position and head extended. The C-arm is rotated to obtain an oblique submental view to visualize the foramen ovale. The skin entry point is ~2–3 cm lateral to the commissura labialis (angle of the mouth) on the affected side. The needle trajectory follows a straight line directed toward the pupil when seen from the front and passes 3 cm anterior to the external auditory meatus when seen from the side.Citation28

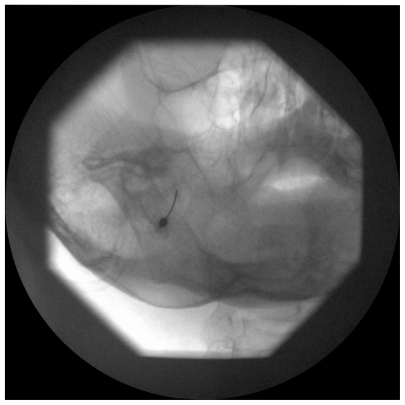

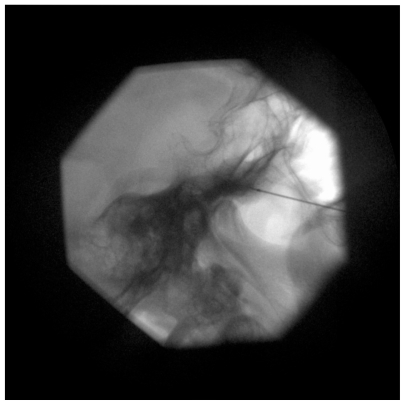

A 22-gauge, 10-cm RF cannula with a 5-mm active tip is used. After administration of local anesthesia, the cannula is advanced in a coaxial manner (tunnel view) to the X-ray beam toward the foramen ovale (). A finger can be placed in the oral cavity to make sure that the buccal mucosa has not been perforated. When the cannula enters the foramen ovale, the depth of the cannula inside the Meckel’s cavity is ascertained on the lateral fluoroscopic view. The electrode is advanced ~2–4 mm further through the canal of the foramen ovale such that the tip of the electrode reaches the junction of the petrous ridge of the temporal bone and the clivus (). The stylet is then removed from the cannula, and aspiration is performed to ensure that there is no CSF or blood. Injecting 0.5 mL contrast dye helps to confirm that the needle has not penetrated the dura.Citation28,Citation29

Test stimulation is mandatory before RF lesioning. The mandibular nerve lies in the lateral portion of the foramen ovale. If the nerve is stimulated at 2 Hz between 0.1 and 1.5 Hz, muscle contraction of the lower jaw may be seen. This confirms that the needle has passed through the foramen ovale and the tip is lying on the trigeminal roots. Next, paresthesia in the concordant trigeminal distribution of the patient’s usual symptoms (V1, V2, or V3 divisions) at 50 Hz, 1 msec pulse duration should be reproducible at 0.1–0.5 V.Citation28,Citation29 If paresthesia is only obtained above 0.5 V stimulation, the needle should be redirected to get the same response at a lower voltage. After appropriate stimulation parameters have been achieved, 0.5 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine with 40 mg of triamcinolone should be injected. After waiting for at least 30 sec, RF lesioning at 60°C is carried out for 60 sec. The needle can be repositioned to repeat RF lesioning if more than one branch of the trigeminal nerve is involved.

Pulsed RF (PRF) is a nondestructive method of delivering RF energy to the trigeminal ganglion. In contrast to conventional RF described above, short bursts of RF current at 42°C are generated with long pauses between bursts to allow heat to dissipate in the target tissue.Citation30 Thermal lesions are not produced by PRF, but recent evidence suggests that microscopic damage to axonal microfilaments and microtubules can occur, with greater changes seen in C fibers than A-β or A-δ fibers.Citation31 However, a recent randomized controlled trial comparing conventional RF with PRF showed that PRF was not effective in reducing pain in patients with TN.Citation32 Therefore, PRF cannot be recommended as the standard therapy for rhizolysis of the trigeminal nerve.

Complications

In a large-scale, long-term follow-up of 1600 patients who had received percutaneous RF rhizotomy of the trigeminal ganglion, complications reported include diminished corneal reflex (5.7%), masseter weakness and paralysis (4.1%), dysesthesia (1%), anesthesia dolorosa (0.8%), keratitis (0.6%), and transient paralysis of cranial nerves III and VI (0.8%). Permanent cranial nerve VI palsy was observed in two patients, CSF leakage in two, carotid-cavernous fistula in one, and aseptic meningitis in one.Citation33

Efficacy

After percutaneous RF rhizotomy, initial pain relief can be achieved in 98% of patients, as high as that obtained with MVD.Citation28 Among the various interventional pain therapies, RF rhizotomy offers the highest rate of complete pain relief.Citation34 Although 15%–20% of patients may experience recurrence pain in 12 months, recurrence rate is the lowest among all the percutaneous techniques.

Long-term efficacy of RF rhizolysis is comparatively lower than that of MVD.Citation35 It can be repeated in the same patient if required. In addition, it is a viable option for poor surgical risk patients or for elderly patients who are not fit for MVD because of lower morbidity and mortality rates associated with RF rhizolysis.

Conclusion

It is important to rule out secondary causes of TN, especially in young patients or patients with bilateral symptoms suggestive of multiple sclerosis. MRI scans should be obtained to help detect the presence of vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve. Medical therapy remains first line in the treatment of TN, and drugs such as carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine can be used. Surgery and interventional pain treatment can be considered in patients who have persistent pain despite drug therapy or who are unable to tolerate adverse effects of drugs.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KatusicSBeardCMBergstralhEKurlandLTIncidence and clinical features of trigeminal neuralgia, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945–1984Ann Neurol199027189952301931

- TölleTDukesESadoskyAPatient burden of trigeminal neuralgia: results from a cross-sectional survey of health state impairment and treatment patterns in six European countriesPain Pract20066315316017147591

- MarbachJJLundPDepression, anhedonia and anxiety in temporomandibular joint and other facial pain syndromesPain198111173847301402

- LoveSCoakhamHBTrigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesisBrain2001124Pt 122347236011701590

- NurmikkoTJEldridgePRTrigeminal neuralgia–pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatmentBr J Anaesth200187111713211460800

- DevorMGovrin-LippmannRRappaportZHMechanism of trigeminal neuralgia: an ultrastructural analysis of trigeminal root specimens obtained during microvascular decompression surgeryJ Neurosurg200296353254311883839

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache SocietyThe international classification of headache disorders: 2nd editionCephalalgia200424 Suppl 1916014979299

- BurchielKJA new classification for facial painNeurosurgery20055351164116614580284

- EllerJLRaslanAMBurchielKJTrigeminal neuralgia: definition and classificationNeurosurg Focus2005185E315913279

- CheshireWPTrigeminal neuralgia: For one nerve a multitude of treatmentsExpert Rev Neurother20077111565157917997704

- WoolfallPCoulthardAPictorail review: trigeminal nerve: anatomy and pathologyBr J Radiol20017488145846711388997

- BagheriSCFarhidvashFPerciaccanteVJDiagnosis and treatment of patients with trigeminal neuralgiaJ Am Dent Assoc2004135121713171715646605

- WiffenPJCollinsSMcQuayHJCarrollDJadadAMooreRAAnticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic painCochrane Database Syst Rev20101CD00113320091515

- WiffenPJMcQuayHJMooreRACarbamazepine for acute and chronic painCochrane Database Syst Rev20053CD00545116034977

- CruccuGGronsethGAlksneJAmerican Academy of Neurology Society; European Federation of Neurological SocietyAAN-EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia managementEur J Neurol200815101013102818721143

- FrommGHTerrenceCFChatthaASBaclofen in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: double-blind study and long-term follow-upAnn Neurol19841532402446372646

- ZakrzewskaJMChaudhryZNurmikkoTJPattonDWMullensELLamotrigine (lamictal) in refractory trigeminal neuralgia: results from a double-blind placebo controlled crossover trialPain19977322232309415509

- JanettaPTrigeminal neuralgia: treatment by microvascular decompressionWilkinsRRegacharySNeurosurgeryNew York, NYMcGraw-Hill199639613968

- HaiJLiSTPanQGTreatment of atypical trigeminal neuralgia with microvascular decompressionNeurol India2006541535616679644

- JannettaPJMcLaughlinMRCaseyKFTechnique of microvascular decompression. Techinical noteNeurosurg Focus2005185E515913281

- SarsamZGarcia-FinanaMNurmikkoTJVarmaTREldridgePThe long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgiaBr J Neurosurg2010241182520158348

- DhopleAAAdamsJRMaggioWWNaqviSARegineWFKwokYLong-term outcomes of Gamma Knife radiosurgery for classic trigeminal neuralgia: implications of treatment and critical review of the literature. Clinical articleJ Neurosurg2009111235135819326987

- RegisJMetellusPHayashiMRousselPDonnetABille-TurcFProspective controlled trial of gamma knife surgery for essential trigeminal neuralgiaJ Neurosurg2006104691392416776335

- OhIHChoiSKParkBJKimTSRheeBALimYJThe treatment outcome of elderly patients with idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: micro-vascular decompression versus gamma knife radiosurgeryJ Korean Neurosurg Soc200844419920419096677

- OmeisISmithDKimSMuraliRPercutaneous balloon compression for the treatment of recurrent trigeminal neuralgia: long-term outcome in 29 patientsStereotact Funct Neurosurg200886425926518552523

- SkirvingDJDanNGA 20-year review of percutaneous balloon compression of the trigeminal ganglionJ Neurosurg200194691391711409519

- CappabiancaPSpazianteRGraziussiGTaglialatelaGPecaCde DivitiisEPercutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizolysis for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Technique and results in 191 patientsJ Neurosurg Sci199539137458568554

- RajPPLouLErdineSStaatsPSWaldmanSDRadiographic Imaging for Regional Anesthesia and Pain ManagementPhiladelphia, PAChurchill Livingstone2003

- TahaJMTewJMJrComparison of surgical treatments for trigeminal neuralgia: reevaluation of radiofrequency rhizotomyNeurosurgery19963858658718727810

- ErdineSRaczGBNoeCSomatic blocks of the head and neckRajPPInterventional Pain Management2nd editionPhiladelphia, PASaunders-Elsevier20088287

- BogdukNPulsed radiofrequencyPain Med20067539640717014598

- ErdineSBilirACosmanERCosmanERJrUltrastructural changes in axons following exposure to pulsed radiofrequency fieldsPain Pract20099640741719761513

- ErdineSOzyalcinNSCimenACelikMTaluGKDisciRComparison of pulsed radiofrequency with conventional radiofrequency in the treatment of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgiaEur J Pain200711330931316762570

- KanpolatYSavasABekarABerkCPercutaneous controlled radiofrequency trigeminal rhizotomy for the treatment of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: 25-year experience with 1600 patientsNeurosurgery200148352453411270542

- LopezBCHamlynPJZakrzewskaJMSystematic review of ablative neurosurgical techniques for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgiaNeurosurgery200454497398215046666

- TatliMSaticiOKanpolatYSindouMVarious surgical modalities for trigeminal neuralgia: literature study of respective long-term outcomesActa Neurochir (Wien)2008150324325518193149