Abstract

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often coadministered with proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) to reduce NSAID-induced gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events. This coadministration is generally regarded as safe, and is included in many of the guidelines on NSAID prescription. However, recent evidence indicates that the GI risks associated with NSAIDs can be potentiated when they are combined with PPIs. This review discusses the GI effects and complications of NSAIDs and how PPIs may potentiate these effects, options for prevention of GI side effects, and appropriate use of PPIs in combination with NSAIDs.

NSAIDs: one of the most widely used therapeutic agents

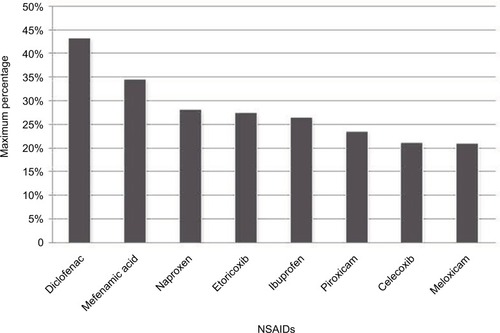

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including both traditional non-selective NSAIDs (ns-NSAIDs) and selective COX2 inhibitors, are among the most widely used of therapeutic agents. Taken alone or in combination with other classes of drugs, they are used for symptomatic treatment across multiple clinical indications, including short- and long-term pain states and a range of musculoskeletal disorders.Citation1,Citation2 Both prescription and over-the-counter NSAIDs are widely used for their anti-inflammatory (AI) and analgesic effects. NSAIDs are an essential choice in pain management, because of the combined role of the COX pathway in inflammation.Citation3 In a meta-analysis examining the sales and essential-medicine lists in countries of different incomes, diclofenac was found to be the most popular NSAID, followed by ibuprofen, mefenamic acid, and naproxen ().Citation1 Etoricoxib was also commonly prescribed in Bangladesh, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Singapore.Citation1

Figure 1 Individual NSAID use as percentagea of total NSAID sales in all countries in 2011.

Abbreviation: NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

NSAID-induced GI injury and the coprescription of PPIs

NSAIDs are a leading cause of drug-related morbidity, especially in the elderly and patients with comorbidities.Citation4 Adverse events associated with NSAIDs are a challenge in treatment optimization for pain.Citation5 Adverse events include alterations in renal function, effects on blood pressure, hepatic injury, and platelet inhibition, which may result in increased bleeding. However, the most important adverse effects of NSAIDs are the gastrointestinal (GI) and cardiovascular adverse effects. A considerable amount of money is spent treating and preventing just the GI events. A Canadian study found that the GI iatrogenic cost factor for NSAIDs was 1.73, meaning that an additional CA$0.73 was spent on the prophylaxis and treatment of NSAID-related GI events for each Canadian dollar of direct cost spent on NSAID.Citation6 The deleterious GI effects of ns-NSAIDs are a cause for concern, because of their frequency and seriousness.Citation3

Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been proven efficacious in healing NSAID-associated ulcers, as they provide potent and long-lasting inhibition of gastric acid secretion.Citation7 As such, they are often coprescribed with NSAIDs. However, this leads to excessive cost for both patients and governments, and also induces a potential risk for iatrogenic harm.Citation8 In the past two decades, the coadministration of NSAIDs and PPIs has resulted in a decrease in upper-GI tract adverse events, but has been associated with an increased frequency of lower-GI tract events. This enteropathy induced by the combination of an NSAID and PPI is common, and lesions induced by these drugs in the small intestine could be of considerable clinical importance.Citation9 The subsequent sections of this manuscript focus on the GI effects/complications of NSAIDs, options for prevention of GI side effects, and appropriate use of PPIs in combination with NSAIDs.

NSAID-related upper- and lower-GI complications

Clinical significance

The extensive use of NSAIDs in prescriptions and by over-the-counter NSAID users has made GI complications a severe problem.Citation10 These complications generally include bleeding gastric and/or duodenal ulcers, and to a lesser extent obstructions and/or perforations.Citation11,Citation12 NSAIDs can cause both upper- and lower-GI complications.Citation13 Although the incidence of upper-GI mucosal damage has decreased over the years, due to the use of PPIs, lower-GI mucosal damage has been steadily increasing.Citation13,Citation14

Although the risk of ulcer complications may decrease after the first few months of NSAID use, it still does not disappear with long-term therapy.Citation15 Also, NSAID use is associated with heightened risks in some patients, and thus awareness of the risk factors and the use of preventive therapy for NSAID-related upper-GI injury is important.Citation16 highlights some of the GI complications associated with NSAID use.

Table 1 Risk factors for GI complications associated with NSAID use

Upper- versus lower-GI complications associated with NSAIDs

Upper-GI complications

The two main mechanisms that are involved in upper-GI complications are systemic inhibition of gastric mucosal protection, through inhibition of COX activity (mostly COX1) of the gastric mucosa, resulting in reduced synthesis of mucus and bicarbonate, an impairment of mucosal blood flow, and an increase in acid secretion; and physicochemical disruption of the gastric mucosal barrier.Citation17 Acid injures the mucosa by H+-ion back-diffusion from the lumen, causing tissue acidosis, and also increases drug absorption, which is inversely proportional to drug ionization.

Clinical impact

According to estimates from the US, nonvariceal upper-GI bleeding results in 400,000 hospital admissions every year, costing more than an annual US$2 billion.Citation18 In addition, despite advances in therapy, rebleeding is common (7%–16%) and the in-hospital mortality rate remains high (3%–14%).Citation19 An observational study conducted in the Spanish national health service found that the incidence of hospital admissions due to major GI events of the entire GI tract was 121.9 events/100,000 persons/year, but those related to the upper GI tract were six times more frequent.Citation20

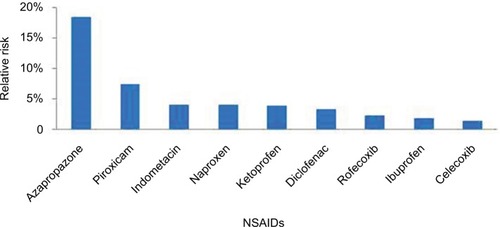

Upper-GI risk profile of various NSAIDs

Different NSAIDs have different upper-GI risks. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies, different NSAIDs, including COX2 inhibitors, showed different risks of upper-GI complications.Citation21 The NSAIDs with the lowest relative risk included celecoxib and ibuprofen, while piroxicam had one of the highest ().Citation21 The use of high daily doses of individual NSAIDs was associated with approximately a two- to threefold increase in relative risk for upper-GI complications compared with the use of low–medium doses, except for celecoxib, for which a dose response was not observed.Citation21 In addition, in the recently published CONCERN trial, where the primary end point was recurrent upper-GI bleeding within 18 months, it was found that celecoxib, a COX2 inhibitor, had a 5.6% cumulative incidence of recurrent bleeding, which was significantly lower than naproxen, which had a 12.3% cumulative incidence.Citation22 This significant difference was observed despite PPIs being given in both the study groups.

Figure 2 Relative risk of upper-GI complications with different NSAIDs.

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Lower-GI complications

Mechanism

The mechanism of NSAID-induced lower-GI damage is very different from upper-GI damage, and is proportional to the acidity of the molecule used and the extent of increased lower-intestine permeability generated by NSAIDs. This increase in permeability always leads to inflammation.Citation23 The development of small-intestine inflammation usually starts with an initial increase in small-intestine permeability.Citation24

Inhibition of both COX1 and COX2 causes small-bowel damage in the long-term. A capsule-endoscopy study found that even though COX2-selective agents resulted in a lower prevalence of damage compared to ns-NSAIDs, there was still a high prevalence of damage seen with COX2-selective agents.Citation25 There has also been increasing evidence that COX2 is needed for the maintenance of mucosal integrity and ulcer healing, and thus gastric and intestinal lesions develop only when both COX1 and COX2 are suppressed.Citation26 ns-NSAIDs are also weakly acidic and are invariably lipophilic, giving them detergent-like properties (). As such, they interact with phospholipids, an essential constituent of the brush border, causing damage to the surface epithelium.Citation27 Moreover, lower-GI injury is not dependent on acid production.Citation28 Therefore, the use of antisecretory agents does not help reduce its incidence.Citation29 However, a lower pKa value for individualized NSAIDs is associated with increased intestinal permeability.Citation30

Table 2 Acidity comparison among NSAIDs

NSAIDs also uncouple mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, which decreases intracellular adenosine triphosphate concentration. This change results in loss of intercellular integrity, as the intercellular junctions are under the control of adenosine triphosphate-dependent actin– myosin complexes, and hence an increase in intestinal permeability and subsequent mucosal damages.Citation27,Citation31

Many studies have suggested that bacteria also play a role in the pathogenesis of NSAID enteropathy. One key observation is that germ-free rats and mice develop little or no intestinal damage when given an NSAID, but become susceptible to NSAID-enteropathy when colonized by Gram-negative bacteria.Citation32 A number of studies have also reported protective effects of antibiotics against NSAID enteropathy, particularly when the antibiotics were effective in attenuating Gram-negative bacteria.Citation32 For example, in a randomized controlled trial in which healthy volunteers were given slow-release diclofenac plus omeprazole and rifaximin extended intestinal release, or slow-release diclofenac plus omeprazole and extended intestinal-release rifaximin, the results showed that fewer rifaximin-treated volunteers developed small-bowel lesions compared with placebo-treated subjects.Citation33 This strengthens the evidence of the role of enteric bacteria in the development of NSAID enteropathy.

Bile and enterohepatic circulation are also important factors in the induction of intestinal damage.Citation32,Citation34 The combination of NSAIDs with bile has been shown to damage cultured intestinal epithelial cells.Citation35 Also, the presence of bacteria can result in the formation of secondary bile acids, which are particularly damaging to these cells.Citation36 There is evidence that the ligation of the bile duct prevents/reduces intestinal damage when NSAIDs are administered to rats.Citation37,Citation38 In addition, animal models have shown that NSAIDs that do not undergo enterohepatic recirculation do not cause significant intestinal damage. This may be related to the recurring injury to the epithelium induced by the NSAID recirculating through the intestine.Citation39

Clinical impact

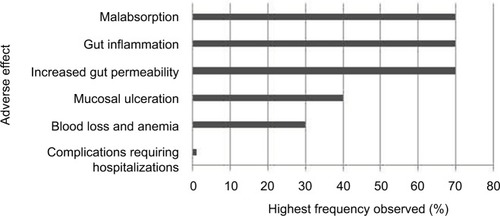

Association of NSAIDs with damage to the lower-GI tract has not been widely studied and remains poorly characterized. NSAID-induced enteropathy has recently gained much attention, due to the introduction of new diagnostic modalities, such as capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy, as well as the increased use of acetylsalicylic acid and NSAIDs. The clinical significance and frequency of risks and complications with ns-NSAIDs in the lower-GI tract have been increasingly reported.Citation13,Citation25 Lower-GI complications also have worse clinical outcomes compared to upper-GI complications ():Citation40 they lead to higher mortality and longer hospitalization.Citation41 Although PPIs are prescribed together with NSAIDs as a form of gastroprotection, not only do they not inhibit NSAID enteropathyCitation29 but also frequent use of PPIs can worsen NSAID-induced small-intestine injury by modifying intestinal microbiota.Citation9

Figure 3 Main adverse effects of NSAIDs in the lower-GI tract.

Abbreviations: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; GI, gastrointestinal.

In recent years, large randomized controlled trials have begun to analyze the effect of NSAIDs on the entire GI tract, rather than just the upper GI tract. In such studies as CONDORCitation42 and GI-REASONS,Citation43 the primary end point was defined as clinically significant events occurring throughout the GI tract. It was seen that celecoxib, a COX2 inhibitor, generally caused fewer upper- and lower-GI events compared to such ns-NSAIDs as naproxen, ibuprofen, and diclofenac. highlights a comparison of lower-GI outcomes in a few major studies.

Table 3 Comparison of lower-GI outcomes

Most patients (80%–100%) have active mucosal lesions in the small bowel after 2 weeks of low-dose NSAID and PPI therapy.Citation44 Evidence from shorter studies in healthy volunteers has also shown that short-term NSAIDs use can also cause NSAID enteropathy. Maiden et al reported that slow-release diclofenac use for 2 weeks resulted in macroscopic injury to the small intestine in up to 75% of subjects.Citation45 Goldstein et al also reported that the background incidence of small-bowel lesions in healthy adults was not insignificant, and 2 weeks of naproxen plus omeprazole resulted in small-bowel mucosal breaks in more than half of volunteers. In comparison, celecoxib was associated with significantly fewer small-bowel mucosal breaks than naproxen plus omeprazole (17% versus 55%).Citation46 Another study comparing celecoxib with ibuprofen/omeprazole found similar results (percentage of subjects with small-bowel mucosal breaks was 25.9% for ibuprofen plus omeprazole compared with 6.4% for celecoxib and 7.1% for placebo).Citation47

Prevention of NSAID-related GI complications: options

Proton-pump inhibitors

PPIs are antisecretory agents that reduce acid secretion for up to 36 hours.Citation48 They are commonly used to prevent NSAID-induced peptic ulceration and mucosal injury.Citation49 Although PPIs have shown to be effective in reducing upper-GI events, video-endoscopy studies have shown that there is a high occurrence of small-intestine damage, despite the fact that patients were given PPIs. Furthermore, animal studies have suggested that PPIs worsen NSAID enteropathy when given together with an NSAID.Citation39

Histamine 2-receptor antagonists

Histamine 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs), which inhibit acid secretion, have also been evaluated for reducing NSAID-associated complications. A meta-analysis of 14 trials found that H2RAs (eg, famotidine and ranitidine) were protective at high doses, but at commonly prescribed doses they reduced the risk of duodenal but not gastric ulcers.Citation50

Misoprostol

Misoprostol (a prostaglandin analogue) protects the GI mucosa by stimulating mucus/bicarbonate secretion and stabilizing barrier function.Citation51 It decreases NSAID-related upper-GI complications by approximately 40% compared with NSAIDs alone.Citation52,Citation53 High-dose misoprostol coadministered with indomethacin was found partially to alleviate indomethacin-induced increase in intestinal permeability.Citation54 Unfortunately, misoprostol is not always well tolerated, due to diarrhea and abdominal pain, preventing continued use; lower doses of misoprostol with a lower frequency of side effects may also be less effective at preventing GI events.Citation55

Enteric-coated NSAIDs

Available data indicate that enteric-coated NSAIDs do not reduce the incidence of upper-GI events compared with other formulations,Citation16 but the use of sustained-release and enteric-coated NSAIDs may possibly shift the site of damage distally.Citation56 However, this phenomenon has not been widely studied. A small study done using video-capsule endoscopy found that even short-term administration of enteric-coated daily aspirin is associated with mucosal abnormalities of the small-bowel mucosa.Citation57

Topical NSAIDs

Topical NSAID formulations can produce higher concentrations of drug in the local tissue, with very low systemic exposure, as measured via plasma concentrations.Citation58 Use of topical NSAIDs may also be associated with fewer severe GI events compared to oral NSAIDs.Citation59 Although topical NSAID formulations have shown to be effective in acute painCitation60 and for short-term use in chronic pain, there are contradictory results regarding topical NSAIDs providing effective long-term pain relief.Citation16

Lower-dose NSAID formulations

New formulations of NSAIDs may reduce risks of adverse events by using lower doses, while providing effective analgesia. There is some evidence that a few NSAIDs, such as diclofenac, could provide effective pain relief at lower doses than are currently used, assuming that 80% inhibition of COX2 is necessary for therapeutic efficacy.Citation61

Selective COX2 inhibitors

Selective inhibition of COX2 leads to decreased inflammation in musculoskeletal tissues, and by sparing COX1, there is a decrease in the incidence of GI mucosal injury.Citation49 Furthermore, some of these inhibitors are effective in preventing lower-GI events, which are largely mediated by the acidic nature of NSAIDs themselves.Citation62 According to the CONDORCitation42 and GI-REASONSCitation43 trials, which looked at both upper- and lower-GI events, only celecoxib has been shown to reduce mucosal harm versus NSAIDs throughout the entire GI tract.

Helicobacter pylori eradication

Studies have shown that Helicobacter pylori infection has a high prevalence rate in Asia – 54%–76%.Citation63 This is of concern, as H. pylori is etiologically associated with gastroduodenal disease, particularly peptic ulcer disease and gastric malignancies.Citation64 In fact, the 2008 American College of Cardiology Foundation–American College of Gastroenterology–American Heart Association expert consensus document on reducing the GI risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use recommends testing for and eradicating H. pylori in patients with a history of ulcer disease before starting chronic antiplatelet therapy.Citation65 The 2009 American College of Gastroenterology guidelines on the prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications also concluded that H. pylori infection increases the risk of NSAID-related GI complications.Citation49 One systematic literature review found that H. pylori eradication in infected patients was equally effective as the use of PPIs in preventing GI complications due to NSAID use.Citation66 However, another meta-analysis revealed that although H. pylori eradication reduces risk, PPIs provides superior ulcer prevention.Citation67

PPIs as standard of care: benefits and risks

The American College of Gastroenterology in 2009 stated that PPIs significantly reduce gastric and duodenal ulcers and their complications in patients taking NSAIDs or COX2 inhibitors.Citation49 Nonetheless, coadministration of PPIs and NSAIDs contributes to an increased risk of adverse events.Citation68

PPIs in comparison with other gastroprotective agents

PPIs control both basal and food-stimulated acid secretions, producing complete and longer-lasting acid suppression than H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs).Citation8 Also, unlike H2RAs, tolerance to PPIs has never been observed.Citation8 Controlled studies of the therapeutic effects of PPIs versus H2RAs for NSAID-associated gastric ulcers have shown that PPIs had a significantly higher healing rate after 8-week treatment compared to H2RAs.Citation7,Citation69 The ASTRONAUT study, which compared omeprazole and ranitidine in the treatment of ulcers associated with NSAIDs, found that at 8 weeks, treatment was successful in a higher percentage of patients on omeprazole (80% for 20 mg, 79% for 40 mg) compared to those on ranitidine (63%).Citation70 Compared to misoprostol, PPIs also appear to be more effective. In a study comparing the two drugs, maintenance therapy with omeprazole was associated with a lower rate of relapse than misoprostol, although the overall rates of successful treatment of ulcers, erosions, and symptoms associated with NSAIDs were similar for 20 mg omeprazole, 40 mg omeprazole, and misoprostol.Citation71 However, a systematic review with network meta-analysis showed that selective COX2 inhibitors provide better GI protection compared with a combination of an ns-NSAID plus PPI.Citation72

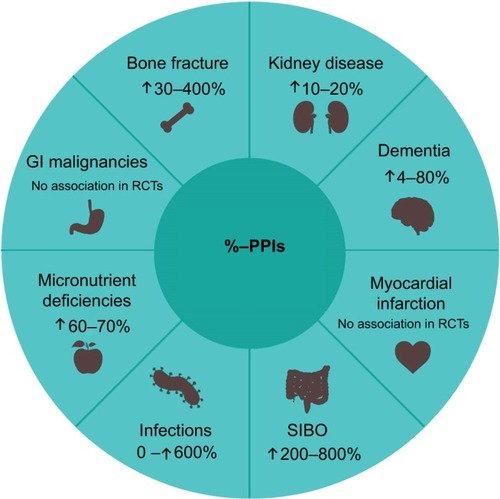

Risks associated with long-term use of PPIs

Patients also experience an increased risk of adverse drug reactions with PPIs.Citation68 These include an increased risk of chronic kidney disease, dementia, bone fracture, myocardial infarction, infections, micronutrient deficiencies, and GI malignancies. highlights the potential adverse effects of PPIs, along with their relative risks. However, the overall quality of evidence is either low or very low.Citation68

Figure 4 Potential adverse effects of PPIs and their relative risks.

Abbreviations: SIBO, small-intestine bacterial overgrowth; GI, gastrointestinal; PPIs, proton-pump inhibitors; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

A randomized placebo-controlled trial comparing celecoxib plus PPI versus celecoxib plus placebo found that a significantly higher proportion of subjects in the COX2 plus PPI group developed small-bowel injury than the COX2 plus placebo group. This further proves that the use of PPIs increases the risk of short-term NSAID-induced small-bowel injury. Because PPIs alone cause neither small-bowel mucosal damage nor inflammation, alteration of the luminal environment by PPIs seems to be an exacerbating factor in NSAID-induced small-bowel injuries.Citation73

In recent years, there has been growing evidence that PPIs can alter the composition of the gut microbiome, exacerbating NSAID-induced small-intestine injury.Citation74,Citation75 Jackson et al reported that PPI users had a significantly lower abundance of gut commensals and lower microbial diversity.Citation75 A study examining the relationship between PPIs and NSAID-induced small-intestine injury also reported that PPIs increased the incidence and severity of NSAID enteropathy, partly due to dysbiosis.Citation28 This is because alteration of intestinal microbiota contributes to low-grade but chronic inflammation.Citation9 A meta-analysis evaluating the association between PPIs and small-intestine bacterial overgrowth concluded that that PPI use was statistically associated with small-intestine bacterial overgrowth risk, suggesting that this effect could possibly be due to chronic acid suppression and the resultant hypochlorhydria associated with PPI use.Citation76 Considering that Gram-negative bacteria are an important factor in the pathogenesis of NSAID enteropathy, it is possible that suppression of acid secretion by a PPI could worsen NSAID-induced small-intestine damage.Citation28

Appropriate use of PPIs: recommendations from international guidelines

There are several guidelines that provide recommendations on the use of PPIs when NSAIDs are used.

2016 Position paper on safe PPI use

Standard-dose PPIs are recommended for patients taking ns-NSAIDs at risk for upper-GI complications (bleeding and perforation) and for those having had an episode of previous GI bleeding and prescribed selective COX2 inhibitors.Citation77 In both ns-NSAID and COX2-selective NSAID users, PPI therapy reduces upper-GI symptoms, in particular dyspepsia.Citation77 However, NSAID-induced adverse events in the lower GI tract are not prevented by PPIs.

American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice updates 2017

The 2017 update recommends that patients take long-term PPIs for NSAID bleeding prophylaxis if at high risk.Citation68

American College of Gastroenterology guidelines on management of bleeding ulcers

In patients with NSAID-associated bleeding ulcers who must resume NSAIDs, it is recommended to give a daily PPI together with a COX2-selective NSAID at the lowest effective dose.Citation78 In patients with low-dose aspirin-associated bleeding ulcers that have been resumed on aspirin for secondary prevention, long-term daily PPI therapy should also be provided.Citation78

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014 guidelines on the investigation and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults

In patients using NSAIDs with diagnosed peptic ulcers, a full-dose PPI or H2RA for 8 weeks should be offered, and NSAIDs should be stopped where possible.Citation79 Further, H. pylori-eradication therapy should be offered if bacteria are present. In high-risk patients (previous ulceration) for whom NSAID continuation is necessary, a PPI together with the NSAID should be prescribed. A COX2-selective NSAID is preferred over a standard NSAID.Citation79

Deprescribing PPIs

Coadministration of NSAIDs–PPIs is widely used and still regarded as safe and standard medical practice.Citation9 Use of PPIs for ulcer prophylaxis in low-risk patients is often perceived by doctors as a harmless and relatively inexpensive remedy.Citation8 Also, many patients continue to take PPIs beyond the recommended course of treatment. This of course has potential for harm, as well as large economic implications.Citation80 Deprescribing PPIs, however, may be important and clinically relevant in many patients taking NSAIDs. For example, patients who require chronic pain medication tend to be older (≥65 years),Citation81 and thus more likely to have comorbidities. Hence, NSAID–PPI coprescription will likely contribute to polypharmacy and increase risks along with additive side effects, especially those affecting the lower GI.

Benefits of deprescribing

Prescribing a PPI together with an NSAID as ulcer prophylaxis is an example of a prescribing cascade. It can result in further harm to the patient.Citation82 As seen from evidence on the effects of PPIs on gut microbiota, we see how a prescribing cascade exacerbates the adverse events of NSAIDs. Deprescribing will reduce the risk of adverse events of NSAIDs. Deprescribing will also decrease risks of nonadherence. A cohort study in Italy found that among the 100 patients recruited, nonadherence was reported for 49 (55.1%) at the first follow-up and 55 (69.6%) at the second follow-up. The number of drugs prescribed at discharge was related to patient lack of adherence at follow-up.Citation83 This may have had a negative impact on the clinical and economic outcomes of patients’ various conditions.

Despite the numerous guidelines on prescribing PPIs and NSAIDs, there is only one on the deprescription of PPIs. Recently, the College of Family Physicians of Canada developed a set of guidelines after a systematic review of PPI-deprescribing trials and examination of reviews of harm from long-term PPI use.Citation80

Recommendations from Canada College of Family Physicians guidelines on deprescribing PPIs

When should PPIs be deprescribed?

Not all patients are suitable candidates for PPI deprescription. Patients with risk factors for GI bleeding or ulcers will have a high risk of relapse, and thus will not be suitable candidates.Citation78 Nonetheless, even though PPIs are widely used as they are seen to be generally safe and effective,Citation84 they should not be continued if they are not indicated. Recent studies have suggested that PPIs alter intestinal microbiota and are involved in the pathogenesis of NSAID enteropathy.Citation85 Adults who have completed a minimum of 4 weeks of PPI treatment for heartburn or mild–moderate gastroesophageal reflux disease or esophagitis whose symptoms are resolved are ideal examples where PPI deprescription should be considered. This should exclude patients with Barrett esophagus, severe esophagitis grade C or D, or documented history of bleeding GI ulcers.Citation80 PPIs, however, should not be deprescribed in chronic NSAID users with bleeding risk.Citation86

How to deprescribe PPIs?

Reducing the dose or switching to on-demand use

The Canadian guidelines strongly recommend lowering the dose or switching to on-demand use.Citation80 Lowering the dose will lead to a lower risk of symptom relapse compared to switching to on-demand use. However, on-demand use will help to lower pill burden and cost.

Abrupt discontinuation or tapering

Alternatively, the PPI can just be discontinued abruptly or tapered slowly. There is evidence that an abrupt discontinuation increases the risk of symptom relapse, and thus patients should be tapered to the lowest effective dose before discontinuation.Citation80 Patients can also be provided symptomatic relief with on-demand PPI.

Monitoring and nonpharmacological management

The patient should be monitored at 4 and 12 weeks for such symptoms as heartburn, dyspepsia, regurgitation, or epigastric pain.Citation80 The patient may exhibit nonverbal symptoms, such as loss of appetite, weight loss, and agitation. If symptoms return, nondrug strategies can be used: avoid meals 2–3 hours before bedtime, elevate head of bed, address need for weight loss, and avoid dietary triggers.Citation87 Over-the-counter drugs, such as H2RAs, PPIs, antacids, and alginates, can also be used, although the use of daily H2RAs is only weakly recommended, due to a higher risk of symptom relapse.

Appropriate use of PPIs in patients on NSAIDs: when and why?

Managing upper-GI damage

According to the guidelines available, PPIs are still essential in the treatment and prophylaxis of NSAID-induced upper-GI injury.Citation86 However, their prescription for this indication should be based on appropriate recommendations from worldwide published guidelines.Citation8 Also, it is essential to reduce their continuation after the patient’s discharge from hospital by assessing the true need on a case-by-case basis and periodically reviewing the long-term intake.Citation8 summarizes some risks and benefits of using PPIs.

Table 4 Benefits versus risks for PPI use

Managing lower-GI damage

Much of the data available are catered toward upper-GI protection. Scarpignato et alCitation77 provided general guidance on prescription of NSAIDs and PPIs based on cardiovascular and GI risk of the patient. However, this was based only on upper-GI risk. At present, there are no comprehensive guidelines on how and when to prescribe PPIs for the prophylaxis of both upper- and lower-GI injury in NSAID users. Although several international guidelines touch on this issue, they do not explicitly state what to do in the event that a low-GI-risk patient becomes a high-risk one or what to do in the event that the first-line decision fails. Perhaps it is time to reconsider the use of PPIs together with NSAIDs.

Switching or starting with a COX2 inhibitor rather than an ns-NSAID

The most updated consensus on chronic NSAID prescription recommends that ns-NSAIDs can be used in patients with low GI risk, but COX2 inhibitors should be prescribed to those with high GI risk.Citation86 Therefore, if a patient develops GI problems during treatment with ns-NSAIDs, he/she could possibly be switched to a COX2 inhibitor. However, even if NSAID therapy is discontinued, lesions in the small intestine tend to persist,Citation87 and thus switching agents may not aid in healing of ulcers. Also, Zhao et al reported that patients on ns-NSAIDs were more likely to switch therapy than those on COX2-specific inhibitors.Citation88

As such, we should question whether switching to COX2 inhibitors is a suitable strategy after a patient who continues to need NSAIDs develops GI ulcers. A meta-analysis found that COX2 inhibitors when compared with NSAIDs plus PPIs significantly reduced the risk of perforation, obstruction, bleeding, diarrhea, and withdrawal due to GI adverse events.Citation89 Perhaps a better strategy would be to start patients on COX2 inhibitors, as they have a lower risk of causing GI events compared to ns-NSAIDs.

Use of probiotics in preventing lower-GI tract injury

Results for probiotic use in preventing NSAID-induced lower-GI injury are promising, showing that probiotic use reduces small-bowel injury in either aspirin or NSAID users.Citation90,Citation91 This suggests a potential strategy for prophylaxis. However, the studies conducted had only a small sample size, and thus larger studies are needed. At present, there is insufficient evidence to recommend a specific probiotic strain to prevent lower-GI injury. However, some bacteria have demonstrated AI activity and a protective effect on intestinal mucosa.Citation85

Use of H2RAs for less profound suppression of acid

Most evidence indicates that PPIs are more effective than H2RAs in the prophylaxis and treatment of NSAID-induced GI injury. Nonetheless, a recent study comparing the efficacy of PPIs vs H2RAs in reducing risk of upper-GI bleeding and ulcers in high-risk users of low-dose aspirin showed that the two agents had similar efficacy in the prevention of recurrent ulcers. These patients had a history on endoscopically confirmed ulcer bleeding, and were restarted of aspirin plus PPI or aspirin plus H2RA after the ulcer was healed.Citation92 Perhaps H2RAs could be used to prevent both upper- and lower-GI injury. H2RAs produce less profound suppression of acid compared to PPIs,Citation93 and could result in less alteration to the gut flora.

Regular monitoring

In a European survey investigating primary-care physician behavior and understanding, it was found that only half of the doctors measured their osteoarthritis patients’ hemoglobin routinely as part of a complete blood count.Citation94 Although GI-injury prophylaxis is important, regular monitoring is still essential to allow early detection of injury so that treatment can be administered, and also to prevent development of complications. Hemoglobin levels can be used as an indicator of GI injury; low hemoglobin and hematocrit are attributable to blood loss in the absence of other evident causes.Citation95 The CONDOR trial, which looked at both upper- and lower-GI events, also investigated the frequency of clinically significant blood loss measured by decreases ≥2 g/dL in hemoglobin throughout the GI tract.Citation42 A drop in hemoglobin ≥2g/dL has been well recognized as a surrogate end point in clinical trials investigating the GI toxicity of NSAIDs conducted over the last 20 years.Citation42,Citation94,Citation96–Citation98

Conclusion

The coprescription of PPIs and NSAIDs has benefited patients at risk of upper-GI ulcers and bleeding. However, this common prescribing practice may have potentially deleterious effects on small-bowel mucosa, possibly through a combination of gut dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability. Accumulating data from several recent large-scale human studies suggest that the use of a lower-acidity COX2 inhibitor may be a suitable strategy for patients who are at high risk of both upper- and lower-GI adverse events.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in conception, design, and analysis and interpretation of data. All authors were also involved in preparation of the manuscript, revising it for important intellectual content and final approval before submitting it for publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Nalini Adele Pinto from Pfizer India Ltd for her editorial support with this manuscript.

Disclosure

SS and GL are employees of Pfizer. VG underwent indirect patient-care pharmacy training for 3 months at Pfizer, Singapore. KAG reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- McGettiganPHenryDUse of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that elevate cardiovascular risk: an examination of sales and essential medicines lists in low-, middle-, and high-income countriesPLoS Med2013102e100138823424288

- CroffordLJUse of NSAIDs in treating patients with arthritisArthritis Res Ther201315Suppl 3S2

- OngCLirkPTanCSeymourRAn evidence-based update on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugsClin Med Res200751193417456832

- WehlingMNon-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in chronic pain conditions with special emphasis on the elderly and patients with relevant comorbidities: management and mitigation of risks and adverse effectsEur J Clin Pharmacol201470101159117225163793

- GadzhanovaSIlomäkiJRougheadEECOX-2 inhibitor and non-selective NSAID use in those at increased risk of NSAID-related adverse eventsDrugs Aging2013301233023179898

- RahmeEJosephLKongSXWatsonDJLeLorierJCost of prescribed NSAID-related gastrointestinal adverse events in elderly patientsBr J Clin Pharmacol200152218519211488776

- ScheimanJMThe use of proton pump inhibitors in treating and preventing NSAID-induced mucosal damageArthritis Res Ther2013153S524267413

- SavarinoVDulbeccoPde BortoliNOttonelloASavarinoEThe appropriate use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): need for a reappraisalEur J Intern Med201737192427784575

- MarliczWLoniewskiIGrimesDSQuigleyEMNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors, and gastrointestinal injury: contrasting interactions in the stomach and small intestineMayo Clin Proc201489121699170925440891

- WangXAspirin-like drugs cause gastrointestinal injuries by metallic cation chelationMed Hypotheses19985032272389578328

- LazzaroniMPorroGBManagement of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal toxicityDrugs20096915169

- ButtJHBarthelJSMooreRAClinical spectrum of the upper gastrointestinal effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: natural history, symptomatology, and significanceAm J Med19888425143279767

- SostresCGargalloCJLanasANonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper and lower gastrointestinal mucosal damageArthritis Res Ther201315Suppl 3S3

- BjarnasonIHayllarJSide effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the small and large intestine in humansGastroenterology19931046183218478500743

- CarsonJLStromBLMorseMLThe relative gastrointestinal toxicity of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugsArch Intern Med19871476105410593496062

- GoldsteinJLCryerBGastrointestinal injury associated with NSAID use: a case study and review of risk factors and preventative strategiesDrug Healthc Patient Saf20157314125653559

- ScarpignatoCBjarnasonIBretagneJTowards a GI safer antiinflammatory therapyGastroenterol Int1999124186215

- KanwalFBarkunAGralnekIMMeasuring quality of care in patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: development of an explicit quality indicator setAm J Gastroenterol201010581710171820686458

- van LeerdamMEpidemiology of acute upper gastrointestinal bleedingBest Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol200822220922418346679

- LanasAPerez-AisaMAFeuFA nationwide study of mortality associated with hospital admission due to severe gastrointestinal events and those associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug useAm J Gastroenterol200510081685169316086703

- CastellsagueJRiera-GuardiaNCalingaertBIndividual NSAIDs and upper gastrointestinal complicationsDrug Saf201235121127114623137151

- ChanFKChingJYTseYKGastrointestinal safety of celecoxib versus naproxen in patients with cardiothrombotic diseases and arthritis after upper gastrointestinal bleeding (CONCERN): an industry-independent, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised trialLancet2017389100872375238228410791

- BjarnasonITakeuchiKBjarnasonAAdlerSTeahonKThe G.U.T. of gutScand J Gastroenterol200439980781515513377

- UtzeriEUsaiPRole of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on intestinal permeability and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseWorld J Gastroenterol201723223954396328652650

- MaidenLThjodleifssonBSeigalALong-term effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 selective agents on the small bowel: a cross-sectional capsule enteroscopy studyClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2007591040104517625980

- HalterFTarnawskiASchmassmannAPeskarBCyclooxygenase 2: implications on maintenance of gastric mucosal integrity and ulcer healing: controversial issues and perspectivesGut200149344345311511570

- BjarnasonITakeuchiKIntestinal permeability in the pathogenesis of NSAID-induced enteropathyJ Gastroenterol200944Suppl 19232919148789

- WallaceJLSyerSDenouEProton pump inhibitors exacerbate NSAID-induced small intestinal injury by inducing dysbiosisGastroenterology2011141413141322e1e521745447

- WatanabeTSugimoriSKamedaNSmall bowel injury by low-dose enteric-coated aspirin and treatment with misoprostol: a pilot studyClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20086111279128218995219

- BjarnasonIThjodleifssonBGastrointestinal toxicity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: the effect of nimesulide compared with naproxen on the human gastrointestinal tractRheumatology (Oxford)199938Suppl 12432

- MatsuiHShimokawaOKanekoTNaganoYRaiKHyodoIThe pathophysiology of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced mucosal injuries in stomach and small intestineJ Clin Biochem Nutr201148210711121373261

- WallaceJLMechanisms, prevention and clinical implications of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-enteropathyWorld J Gastroenterol201319121861187623569332

- ScarpignatoCDolakWLanasARifaximin reduces the number and severity of intestinal lesions associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in humansGastroenterology20171525980982e328007576

- WallaceJLNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and gastroenteropathy: the second hundred yearsGastroenterology19971123100010169041264

- YamadaTDeitchESpecianRDPerryMASartorRBGrishamMBMechanisms of acute and chronic intestinal inflammation induced by indomethacinInflammation19931766416627906675

- SyerSDBlacklerRWMartinRNSAID enteropathy and bacteria: a complicated relationshipJ Gastroenterol201550438739325572030

- ReuterBKDaviesNMWallaceJLNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy in rats: role of permeability, bacteria, and enterohepatic circulationGastroenterology199711211091178978349

- KentTHCardelliRMStamlerFWSmall intestinal ulcers and intestinal flora in rats given indomethacinAm J Pathol19695422372495765565

- WallaceJLNSAID gastropathy and enteropathy: distinct pathogenesis likely necessitates distinct prevention strategiesBr J Pharmacol20121651677421627632

- LanasASopeñaFNonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and lower gastrointestinal complicationsGastroenterol Clin North Am200938233335219446262

- LanasAGarcia-RodriguezLAPolo-TomasMTime trends and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in clinical practiceAm J Gastroenterol200910471633164119574968

- ChanFKLanasAScheimanJBergerMFNguyenHGoldsteinJLCelecoxib versus omeprazole and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (CONDOR): a randomised trialLancet2010376973617317920638563

- CryerBLiCSimonLSSinghGStillmanMJBergerMFGI-REASONS: a novel 6-month, prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint (PROBE) trialAm J Gastroenterol2013108339240023399552

- KuramotoTUmegakiENoudaSPreventive effect of irsogladine or omeprazole on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced esophagitis, peptic ulcers, and small intestinal lesions in humans, a prospective randomized controlled studyBMC Gastroenterol2013138523672202

- MaidenLThjodleifssonBTheodorsAGonzalezJBjarnasonIA quantitative analysis of NSAID-induced small bowel pathology by capsule enteroscopyGastroenterology200512851172117815887101

- GoldsteinJLEisenGMLewisBGralnekIMZlotnickSFortJGVideo capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placeboClin Gastro-enterol Hepatol200532133141

- GoldsteinJEisenGLewisBSmall bowel mucosal injury is reduced in healthy subjects treated with celecoxib compared with ibuprofen plus omeprazole, as assessed by video capsule endoscopyAliment Pharmacol Ther200725101211122217451567

- AbrahamNSHlatkyMAAntmanEMACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 expert consensus document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID useJ Am Coll Cardiol201056242051206621126648

- LanzaFLChanFKQuigleyEMGuidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complicationsAm J Gastroenterol2009104372873819240698

- RostomAWellsGTugwellPWelchVDubéCMcGowanJThe prevention of chronic NSAID induced upper gastrointestinal toxicity: a Cochrane collaboration metaanalysis of randomized controlled trialsJ Rheumatol20002792203221410990235

- DajaniEAgrawalNProtective effects of prostaglandins against nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal mucosal injuryInt J Clin Pharmacol Res1989963593692699464

- SilversteinFEGrahamDYSeniorJRMisoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialAnn Intern Med199512342412497611589

- BocanegraTSWeaverALTindallEADiclofenac/misoprostol compared with diclofenac in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee or hip: a randomized, placebo controlled trialJ Rheumatol1998258160216119712107

- DaviesNMSalehJYSkjodtNMDetection and prevention of NSAID-induced enteropathyJ Pharm Pharm Sci20003113715510954683

- RostomADubéCWellsGAPrevention of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcersCochrane Database Syst Rev20024CD002296

- DaviesNMSustained release and enteric coated NSAIDs: are they really GI safe?J Pharm Pharm Sci19992151410951657

- SmecuolESanchezMISuarezALow-dose aspirin affects the small bowel mucosa: results of a pilot study with a multidimensional assessmentClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20097552452919249402

- RolfCEngströmBBeauchardCJacobsLLe LibouxAIntra-articular absorption and distribution of ketoprofen after topical plaster application and oral intake in 100 patients undergoing knee arthroscopyRheumatology (Oxford)199938656456710402079

- MakrisUEKohlerMJFraenkelLAdverse effects of topical non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs in older adults with osteoarthritis: a systematic literature reviewJ Rheumatol20103761236124320360183

- MasseyTDerrySMooreRAMcQuayHJTopical NSAIDs for acute pain in adultsCochrane Database Syst Rev20106CD007402

- HeckenASchwartzJIDepréMComparative inhibitory activity of rofecoxib, meloxicam, diclofenac, ibuprofen, and naproxen on COX-2 versus COX-1 in healthy volunteersJ Clin Pharmacol200040101109112011028250

- BjarnasonIScarpignatoCTakeuchiKRainsfordKDeterminants of the short-term gastric damage caused by NSAIDs in manAliment Pharmacol Ther20072619510617555426

- EusebiLHZagariRMBazzoliFEpidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infectionHelicobacter201419Suppl 115

- FockKMKatelarisPSuganoKSecond Asia-Pacific consensus guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infectionJ Gastroenterol Hepatol200924101587160019788600

- BhattDLScheimanJAbrahamNSACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus DocumentsJ Am Coll Cardiol200852181502151719017521

- LeontiadisGSreedharanADorwardSSystematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in acute upper gastrointestinal bleedingHealth Technol Assess20071151iiiiv1164

- VergaraMCatalanMGisbertJCalvetXMeta-analysis: role of Helicobacter pylori eradication in the prevention of peptic ulcer in NSAID usersAliment Pharmacol Ther200521121411141815948807

- FreedbergDEKimLSYangYXThe risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological AssociationGastroenterology2017152470671528257716

- NemaHKatoMComparative study of therapeutic effects of PPI and H2RA on ulcers during continuous aspirin therapyWorld J Gastroenterol201016425342534621072898

- YeomansNDTulassayZJuhászLA comparison of omeprazole with ranitidine for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugsN Engl J Med1998338117197269494148

- HawkeyCJKarraschJASzczepañskiLOmeprazole compared with misoprostol for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugsN Engl J Med1998338117277349494149

- YuanJTsoiKYangMSystematic review with network meta-analysis: comparative effectiveness and safety of strategies for preventing NSAID-associated gastrointestinal toxicityAliment Pharmacol Ther201643121262127527121479

- WashioEEsakiMMaehataYProton pump inhibitors increase incidence of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small bowel injury: a randomized, placebo-controlled trialClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2016146809815e126538205

- FujimoriSWhat are the effects of proton pump inhibitors on the small intestine?World J Gastroenterol201521226817681926078557

- JacksonMAGoodrichJKMaxanMEProton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiotaGut201665574975626719299

- LoWKChanWWProton pump inhibitor use and the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a meta-analysisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201311548349023270866

- ScarpignatoCGattaLZulloABlandizziCEffective and safe proton pump inhibitor therapy in acid-related diseases: a position paper addressing benefits and potential harms of acid suppressionBMC Med20161417927825371

- LaineLJensenDMManagement of patients with ulcer bleedingAm J Gastroenterol2012107334536122310222

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceGastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease and Dyspepsia in Adults: Investigation and ManagementLondonNICE2014

- FarrellBPottieKThompsonWDeprescribing proton pump inhibitors: evidence-based clinical practice guidelineCan Fam Physician201763535436428500192

- ReidMCEcclestonCPillemerKManagement of chronic pain in older adultsBMJ2015350h53225680884

- KalischLMCaugheyGERougheadEEGilbertALThe prescribing cascadeAust Prescr2011346162166

- PasinaLBrucatoAFalconeCMedication non-adherence among elderly patients newly discharged and receiving polypharmacyDrugs Aging201431428328924604085

- YangYXMetzDCSafety of proton pump inhibitor exposureGastroenterology201013941115112720727892

- LuéALanasAProtons pump inhibitor treatment and lower gastrointestinal bleeding: balancing risks and benefitsWorld J Gastroenterol20162248104771048128082800

- ScarpignatoCLanasABlandizziCLemsWFHermannMHuntRHSafe prescribing of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with osteoarthritis: an expert consensus addressing benefits as well as gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risksBMC Med2015135525857826

- TachecíIBradnaPDoudaTNSAID-induced enteropathy in rheumatoid arthritis patients with chronic occult gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective capsule endoscopy studyGastroenterol Res Pract2013201326838224382953

- ZhaoSZWentworthCBurkeTAMakuchRWDrug switching patterns among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis using COX-2 specific inhibitors and non-specific NSAIDsPharma-coepidemiol Drug Saf2004135277287

- JarupongprapaSUssavasodhiPKatchamartWComparison of gastrointestinal adverse effects between cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and non-selective, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs plus proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Gastroenterol201348783083823208017

- MontaltoMGalloACuriglianoVClinical trial: the effects of a probiotic mixture on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy – a randomized, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled studyAliment Pharmacol Ther201032220921420384610

- EndoHHigurashiTHosonoKEfficacy of Lactobacillus casei treatment on small bowel injury in chronic low-dose aspirin users: a pilot randomized controlled studyJ Gastroenterol201146789490521556830

- ChanFKKyawMTanigawaTSimilar efficacy of proton-pump inhibitors vs H2-receptor antagonists in reducing risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding or ulcers in high-risk users of low-dose aspirinGastroenterology20171521105110e127641510

- LahnerEAnnibaleBDelle FaveGSystematic review: impaired drug absorption related to the co-administration of antisecretory therapyAliment Pharmacol Ther200929121219122919302263

- WalkerCFaustinoALanasAMonitoring complete blood counts and haemoglobin levels in osteoarthritis patients: results from a European survey investigating primary care physician behaviours and understandingOpen Rheumatol J2014811011525598854

- MushlinSBGreeneHLDecision Making in Medicine: An Algorithmic Approach3rd edSt LouisMosby2010

- BombardierCLaineLReicinAComparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritisN Engl J Med2000343211520152811087881

- SchnitzerTJBurmesterGRMyslerEComparison of lumiracoxib with naproxen and ibuprofen in the Therapeutic Arthritis Research and Gastrointestinal Event Trial (TARGET), reduction in ulcer complications: randomised controlled trialLancet2004364943566567415325831

- ChanFKCryerBGoldsteinJLA novel composite endpoint to evaluate the gastrointestinal (GI) effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs through the entire GI tractJ Rheumatol201037116717419884267

- LanasATorneroJZamoranoJLAssessment of gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk in patients with osteoarthritis who require NSAIDs: the LOGICA studyAnn Rheum Dis20106981453145820498210

- AgrawalNRisk factors for gastrointestinal ulcers caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)J Fam Pract19913266196242040888

- TeagardenDLNemaSCase study – parecoxib: a prodrug of valdecoxibProdrugs200713351346

- RordorfCMChoiLMarshallPMangoldJBClinical pharmacology of lumiracoxib: a selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitorClin Pharmacokinet200544121247126616372823

- OkumuADiMasoMLöbenbergRComputer simulations using GastroPlus to justify a biowaiver for etoricoxib solid oral drug productsEur J Pharm Biopharm2009721919819056493

- KhazaeiniaTJamaliFA comparison of gastrointestinal permeability induced by diclofenac phospholipid complex with diclofenac acid and its sodium saltJ Pharm Pharm Sci20036335235914738716

- CannonCPCurtisSPFitzGeraldGACardiovascular outcomes with etoricoxib and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in the Multinational Etoricoxib and Diclofenac Arthritis Long-term (MEDAL) programme: a randomised comparisonLancet200636895491771178117113426

- NissenSEYeomansNDSolomonDHCardiovascular safety of celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen for arthritisN Engl J Med20163752519252927959716

- PfizerProspective randomized evaluation of celecoxib integrated safety vs ibuprofen or naproxen (PRECISION) Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00346216?term=COX-2+inhibitor+AND+arthritis&recr=Open&rank=10.NLMidentifier:NCT00346216Accessed September 5, 2017