Abstract

Background and purpose

Cardiac surgical pain remains a clinical challenge affecting about 40% of individuals in the first six months post-cardiac surgery, and continues up to two years after surgery for about 15–20%. Self-perceived sensitivity to pain may help to identify individuals at risk for persistent cardiac surgical pain to optimize health care responses. The purpose of this study was to assess the relationship between self-perceived pain sensitivity assessed by the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire (PSQ) and postoperative worst pain intensity up to 12 months after cardiac surgery. Sex differences in baseline characteristics and the PSQ scores were also assessed.

Methods

This study was performed among 416 individuals (23% women) scheduled for elective coronary artery bypass graft and/or valve surgery between March 2012 and September 2013. A secondary data-analysis was utilized to explore the relationship between preoperative PSQ scores and worst pain intensity rated preoperatively, across postoperative Days 1–4, at 2 weeks, and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-surgery. Linear mixed model analyses were performed to estimate changes in pain intensity during 1-year follow-up.

Results

The mean (±standard deviation) PSQ-total score was 3.3±1.4, with similar scores in men and women. The PSQ-total score was significantly associated with higher worst pain intensity ratings adjusted for participant characteristics (p=0.001).

Conclusion

Use of the PSQ before surgery may predict cardiac surgical pain intensity. However, previous evidence is limited and not consistent, and more research is needed to substantiate our results.

Introduction

Individuals undergoing cardiac surgery could be affected by persistent cardiac surgical pain. According to a recent meta-analysis including 11,057 individuals,Citation1 cardiac surgical pain affects 37% of individuals in the first 6 months post-cardiac surgery, and for 17% the pain continues up to 2 years after surgery. For 50%, the pain persisted in the moderate/severe range at 24 months. Despite high heterogeneity across studies, persistent cardiac surgical pain remains as a significant clinical challenge; it impairs physical functioning and health-related quality of life (HRQoL),Citation2–Citation4 and estimates suggest that each person developing persistent surgical pain annually costs the North American health care system US$41,000.Citation5

Despite research efforts,Citation6–Citation8 it has been difficult to identify individuals who are susceptible to more severe postoperative pain than others.Citation7 Higher ratings of acute pain intensity and risk for persistent cardiac surgical pain have been linked to female sex,Citation9–Citation11 younger age,Citation3,Citation12 lower socioeconomic status (e.g., lower education, living alone),Citation11 comorbidities,Citation11 preoperative pain,Citation3 and analgesic consumption in the early postoperative phase.Citation9,Citation11 However, individuals’ pain experiences also revolve around their response to psychological, social, and emotional stimuli,Citation6 which may explain variability in self-perceived pain sensitivity and why clinical and demographic factors are not consistently found to influence the risk for persistent surgical pain.Citation6 In this context, preoperative self-perceived sensitivity to pain represents an interesting opportunity to identify individuals at risk for subsequent higher postoperative pain intensity ratings to tailor and optimize postoperative health care responses.Citation13

Eighteen studies have assessed self-perceived pain sensitivity with the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire (PSQ), which is based on ratings of 17 imagined painful situations occurring in daily life;Citation14 six of these studies were conducted in a surgical population comprising data from 830 participants, including 581 (70%) women. The PSQ, based on self-report, is proposed to be a clinical screening tool which could be an alternative to experimental pain sensitivity assessment.Citation7 With a quick and cost-effective administration, the PSQ may help to identify individuals at risk for poor outcomes after surgery.Citation15 From the previous research findings,Citation7,Citation15 the PSQ scores are associated with experimental pain responses in healthy adults. Individuals with persistent pain have been found to exhibit significantly elevated PSQ scores relative to those without persistent pain.Citation16 PSQ scores were associated with pain spreading (i.e., pain sites, pain type), pain intensity, female sex, and increasing age in a larger cross-sectional study (N=6,477),Citation17 and with pain intensity among individuals with lower back problems.Citation18 Depression and anxiety symptoms,Citation18 and pain catastrophizingCitation14,Citation20 are also found to contribute to higher PSQ scores. In the context of surgical pain, two studies have demonstrated an association between PSQ scores and acute postoperative pain after breast cancer surgery.Citation21,Citation22 PSQ scores were positively associated with more severe postoperative acute pain intensity among individuals undergoing abdominal, lung, or thyroid gland surgery,Citation23 and up to 1 year after spinal cord surgery.Citation24 In addition, the PSQ scores predicted functional outcome 2 years after lumbar disc herniation surgery.Citation25 In contrast, Valeberg et alCitation26 observed that lower scores on one of the PSQ’s subscales were associated with postoperative pain intensity in responders younger than 70 years 8 weeks after total knee arthroplasty.

There is some evidence to suggest that the PSQ scores are associated with pain responses in healthy adults and acute pain after surgery. However, the evidence is scant and there is a lack of longitudinal studies. No study has explored the associations between self-perceived sensitivity to pain and pain in the cardiac surgery population. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the relationship between self-perceived pain sensitivity assessed by the PSQ and postoperative worst pain intensity up to 12 months after cardiac surgery. Sex differences in baseline characteristics and the PSQ scores were also assessed.

Materials and methods

This study was performed among 416 individuals (23% women, n=94) from two, separate cardiothoracic surgical units at Oslo University Hospital, Norway, between March 2012 and September 2013 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01976403). A detailed description was previously published.Citation27

In short, the respondents were randomly assigned via a computerized program to receive either a post-discharge pain management booklet intervention or usual care. Inclusion criteria included individuals: 1) undergoing elective isolated coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) and/or isolated valve surgery, 2) ≥18 years old, 3) able to speak and read Norwegian, and 4) able to care for themselves post-discharge. Participants were excluded if they spent more than 12 hours in the intensive care unit. We obtained measures at baseline prior to surgery, across postoperative Days 1–4, at 2 weeks, and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-surgery. In this context, we utilized a secondary data-analysis to expand upon the clinical trial data with a focus on all post-surgery assessments of postoperative pain. As no between-group differences were found in the main trial related to any of the outcomes,Citation27 the whole sample was included for analysis in the present study. Ethics approval was granted by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics in Eastern Norway, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Self-reported measures

Participants completed the demographic form prior to surgery, including level of education and marital status.

Pain sensitivity was assessed prior to surgery and was measured using the Norwegian version of the PSQ.Citation14,Citation15 The PSQ includes 17 items, which assess different types of pain (hot, cold, sharp, and blunt) and different locations (head, and upper and lower extremities). Respondents rated 17 imagined painful situations occurring in daily life on a numeric rating scale, ranging from 0 (not painful) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). Three of the PSQ items work as a sensory reference by describing situations that are not normally considered as painful by people in general, and these items are not included in the final score. The other 14 items relate to situations that are perceived to be painful by most healthy individuals. The pain sensitivity is measured through PSQ as a mean of all items (PSQ-total) and divided into two subscales, each consisting of seven items: PSQ-minor, which represents less painful situations, and PSQ-moderate, which represents moderately painful situations. The PSQ obtained a test–retest intraclass correlation of 0.72 (PSQ-total) when validated in a persistent pain population.Citation16 The Norwegian validation study among healthy adults (N=331, 76% women) resulted in a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 for PSQ-total, 0.90 for PSQ-moderate, and 0.85 for PSQ-minor.Citation14 In the present study, we obtained a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 for PSQ-total, 0.91 for PSQ-moderate, and 0.87 for PSQ-minor. The PSQ-total was used in the analyses with higher scores indicating higher pain sensitivity in the present manuscript.

Additional medical conditions prior to surgery were assessed using the Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ-16),Citation28 which includes 15 common medical conditions and one optional item. Respondents indicated if they had any of the listed medical conditions, if they had received treatment for it, and if their activities were limited, by answering “yes/no”. The total number of comorbidities was used in the current study. The SCQ-16 has obtained a pretest reliability of 0.94 (i.e., intraclass correlation).Citation28

Worst pain intensity was rated at all measurement points using an item from the Brief Pain Inventory Short Form (BPI-SF).Citation29 The BPI-SF showed satisfactory psychometric properties in the Norwegian validation studyCitation30 and is a reliable and valid scale for assessing acute and persistent pain in individuals after cardiac surgery. Worst pain intensity in the last 24 hours was captured using a 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as you can imagine) numeric rating scale.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and proportions and compared with chi-square test, whereas continuous variables were summarized as means with standard deviations and compared with a Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test.

Using a linear mixed model, the association between the PSQ-total score and worst pain intensity up to 12 months post-surgery was examined. The model included fixed effects for time after surgery, sex, age, education (primary school and greater than primary school), marital status (married/cohabitant/partner or living alone [divorced/widowed/single]), and number of comorbidities. Based on our previous findings,Citation11 an interaction term between sex and marital status was added to the model. Random effects of participants and time after surgery were also included. The correlation structure was selected to be unstructured based on the Aikaike information criterion.Citation31 Worst pain intensity was found to have a curvilinear relationship with time, and the inclusion of a quadratic term for time resulted in a significant improvement in model fit over a simple linear model. After model fit, we estimated values for three scores of PSQ-total at each time point by including an interaction term between time and PSQ. The three values were rounded to the nearest whole number and represented median and range (i.e., minimum and maximum) for PSQ-total obtained in the present study. A margins plot was utilized to graphically illustrate the relationship between worst pain intensity at each measurement point given at these three levels of the PSQ-total.

Associations were considered statistically significant if p≤0.05, and all tests were two-tailed. We used Stata 13SE to perform the statistical analyses.Citation32

Results

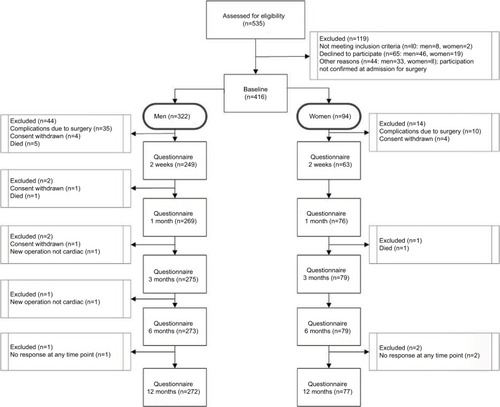

Eighty-four per cent (n=349) of the 416 participants assessed at baseline completed the 12-month assessment (). Participant age ranged between 32 and 88 years. Women (23%, n=94) were more likely to be widowed or single, and they reported lower levels of educational attainment compared to men. Most women were undergoing isolated valve surgery (61%, n=57), and most men were scheduled for isolated CABG surgery (51%, n=165), which involved internal mammary artery grafts with additional saphenous grafts. Sixty-six per cent (n=59) of women compared to 48% (n=144) of men presented with more than one comorbid condition (). Prior to surgery, no differences between men and women were observed for worst pain intensity; however, women experienced significantly more severe worst pain intensity at 3, 6, and 12 months compared to men ().

Table 1 Participant characteristics stratified by sex (N=416)

Table 2 Pain sensitivity ratings at inclusion and worst pain intensity during 1-year follow-up stratified by sex

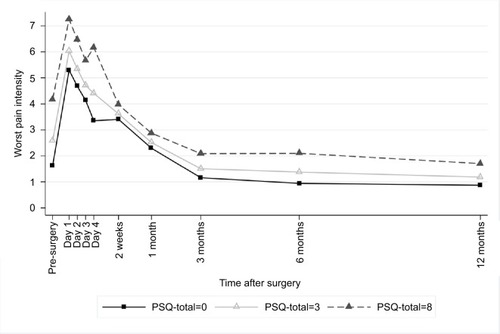

In the present study, mean PSQ scores were 3.3±1.4 (PSQ-total), 4.5±1.7 (PSQ-moderate), and 2.1±1.3 (PSQ-minor); the only sex difference observed was related to PSQ-minor subscale (p=0.01, ). PSQ-total ranged from 0.4 to 8.4 (median 3.15). For PSQ-total score 0, the mean worst pain intensity rating changed during follow-up from 1.9 pre-surgery, to maximum 5.3 at postoperative Day 1, and then to 0.9, 1 year post-surgery (). Similar developments were observed for PSQ-total scores 3 and 8, but on a slightly higher level of worst pain intensity.

Figure 2 Association between pain sensitivity and worst pain intensity across time.

Abbreviation: PSQ, Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire.

Table 3 Linear mixed model for worst pain intensity during 1-year follow-up after cardiac surgery

According to the mixed model, PSQ-total and number of comorbidities were significantly positively associated with more severe worst pain intensity, whereas age was negatively associated with worst pain intensity (). For women only, marital status (i.e., divorced/widowed/single) was associated with higher worst pain intensity ratings over the study period (p=0.023), whereas no effect of marital status was shown among men.

Discussion

This is the first longitudinal study assessing the relationship between self-perceived pain sensitivity measured with the PSQ and cardiac surgical pain. The PSQ-total scores were associated with higher worst pain intensity ratings across the study period. Worst pain intensity was also associated with participants’ comorbid condition, younger age, and women’s marital status. Women who reported living alone at the time of surgery experienced a slower and more challenging functional and emotional recovery related to postoperative pain intensity compared to men, as previously published.Citation2,Citation11,Citation33

The PSQ-total was associated with both acute pain (i.e., worst pain intensity at Days 1–4, 2 weeks, and 1 month) and persistent worst pain intensity (i.e., worst pain intensity at 3, 6, and 12 months) in the present study. The positive association between PSQ scores and acute pain replicates and extends findings from previous studies conducted in the surgical population.Citation21–Citation23 However, previous findings have not been entirely consistent. Ruscheweyh et alCitation21 (N=74) found a moderate association (r=0.57) between PSQ-total and acute pain intensity after breast cancer surgery among women with preoperative persistent pain. In a larger study in the same population, Rehberg et alCitation22 (N=198) found that one unit increase in the PSQ score was associated with 3% increased odds (95% confidence interval: 1.01, 1.05) for rating pain intensity >3 during the first 24 hours after surgery, independent of preoperative pain status. Likewise, Duchow et alCitation23 (N=162) reported that patients with higher pain sensitivity (i.e., PSQ scores) experienced significantly higher acute postoperative pain after abdominal, lung, or thyroid gland surgery when resting in bed and when ambulating compared with patients with low pain sensitivity. However, the classification of the PSQ scores in Duchow et al’s studyCitation23 was based on the PSQ percentiles and the sample included a broad range of surgical procedures. In the three latter studies, acute pain intensity was only assessed on postoperative Day 1Citation21–Citation23 and postoperative Day 2.Citation23 Our study appears to be the first to report findings about PSQ-total and worst pain intensity across postoperative Days 1–4 and later in the early postoperative period. Therefore, the evidence remains inconclusive about the associations between PSQ scores and acute postoperative pain intensity.

Few studies have investigated the association between the PSQ scores and persistent surgical pain intensity. Kim et alCitation24 (N=107) observed that improvements in pain intensity in the low-PSQ-score group (i.e., score <5) were superior to those in the high-PSQ-score group (i.e., score ≥7) up to 1 year after spinal cord surgery. However, the verification for the cut-off values in the latter study is unclear, and the minimal clinically important difference for the PSQ is not established.Citation17 Another study examined the relationship between pain sensitivity measured by the PSQ and postoperative pain 8 weeks after total knee arthroplasty.Citation26 In contrast to our results, the investigators observed that lower PSQ-minor scores were associated with higher pain intensity in patients younger than 70 years. However, the study was limited by a small sample size and lack of adjustment for other factors, which restricts the generalizability of the results. Azimi and BenzelCitation25 (N=154) suggested that a PSQ cut-off value of >5.2 could predict surgical success 2 years after lumbar disc herniation surgery. However, the clinical relevance of the results in the latter study is not clear, and no covariate adjustments were performed.

Similar to our previous findings,Citation11,Citation34 the number of comorbidities was associated with more severe worst pain intensity. Comorbid conditions complicate and cause functional and emotional impairment in the daily life of men and women following cardiac surgery.Citation3,Citation4 In our sample, both men and women reported associated back/neck problems, depression, and persistent pain intensity with lower HRQoL up to 12 months after surgery.Citation2 The differences in pain experience in individuals with depression compared to individuals without depression seem to be pronounced. In a cross-sectional study (N=1,191), Hermesdorf et alCitation19 found that depressed individuals had lower pressure pain thresholds (i.e., obtained from experimental testing) and higher PSQ-minor scores compared to the controls. Anxiety often coexists with depression,Citation35 and among patients with depression in the Hermesdorf et al study,Citation19 severity of anxiety symptoms was found to be the strongest predictor of PSQ-minor scores. Interestingly, in the Korean validation study,Citation20 PSQ had a significant correlation with the pain catastrophizing scale in patients with degenerative lumbar disease, similar to the results from the original validation study.Citation14 However, the relationship between self-perceived pain sensitivity, pain intensity, and depression or anxiety can be independent or interrelated, with either one causing the other, and the reason for this is not clear.

We did not observe any sex difference related to PSQ-total in the present study; however, Larsson et alCitation17 observed that increases in PSQ score were steeper in women for higher self-reported pain intensity and a greater number of pain locations. It is noteworthy that all studies using the PSQ included samples with a higher proportion of women (ranging from 51% to 100%), but only Larsson et alCitation17 observed/reported on sex differences.

The PSQ score has been shown to correlate with experimental-obtained pain intensity ratings in healthy adults and among individuals with persistent pain. However, Ruscheweyh et alCitation36 failed to find associations between basal pain sensitivity, both experimental and self-perceived (PSQ), and treatment outcomes of a 4-week multidisciplinary pain treatment program (N=65). Nevertheless, FillingimCitation6 suggests that individual differences in pain responses, such as pain sensitivity, represent an important clinical opportunity in the assessment and management of pain, endorsing individual treatment tailoring to improve outcomes.

Our results support the use of PSQ scores to predict surgical pain intensity; however, previous evidence is limited and not consistent. The PSQ is validated in German,Citation14 English,Citation18 Chinese,Citation37 Iranian,Citation38 Korean,Citation20 and NorwegianCitation15 populations; however, our sample was ethnically homogeneous. There is a need to further evaluate the PSQ in more diverse samples with participants from different ethnic/cultural backgrounds. For example, Bell et alCitation39 found that PSQ scores and pain intensity scores obtained from experimental testing were elevated in individuals self-identifying as African American compared to non-Hispanic white in a sample scheduled for a low-back interventional procedure. Moreover, Meiselles et alCitation7 suggest that even a single item from the PSQ could be used to evaluate sensitivity to pain, indicating that it is not clear if the PSQ in its current form is the most optimal measure for self-perceived pain sensitivity assessment.

Despite the strength of our study with a larger sample size, longitudinal design, and the higher number of pain assessments, future research is required to substantiate our results. Clearly, more research is needed on the strength and weaknesses of the PSQ, especially in terms of its ability to predict cardiac surgery pain intensity.

Conclusion

Total score for pain sensitivity (PSQ) was significantly associated with worst pain intensity up to 1 year after cardiac surgery. More interventional studies focusing on pain intensity reduction related to pain sensitivity score are warranted to develop better direct treatment and support strategies for individuals undergoing cardiac surgery.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (grant number 2012030).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Guimaraes-PereiraLReisPAbelhaFPersistent postoperative pain after cardiac surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis regarding incidence and pain intensityPain20171581869188528767509

- BjornnesAKParryMFalkRImpact of marital status and comorbid disorders on health-related quality of life after cardiac surgeryQual Life Res2017262421243428484915

- VealFCBereznickiLRThompsonAJPain and functionality following sternotomy: a prospective 12-month observational studyPain Med2016171155116226814306

- KurfirstVMokráčekAKrupauerováMHealth-related quality of life after cardiac surgery-the effects of age, preoperative conditions and postoperative complicationsJ Cardiothorac Surg201494624618329

- KatzJWeinribAFashlerSRThe Toronto General Hospital Transitional Pain Service: development and implementation of a multidisciplinary program to prevent persistent postsurgical painJ Pain Res2015869570226508886

- FillingimRBIndividual differences in pain: understanding the mosaic that makes pain personalPain2017158Suppl 1S11S1827902569

- MeisellesDAviramJSuzanEDoes self-perception of sensitivity to pain correlate with actual sensitivity to experimental pain?J Pain Res201710265729180892

- EltumiHGTashaniOAEffect of age, sex and gender on pain sensitivity: a narrative reviewOpen Pain J2017104455

- ChoiniereMWatt-WatsonJVictorJCPrevalence of and risk factors for persistent postoperative nonanginal pain after cardiac surgery: a 2-year prospective multicentre studyCMAJ2014186E213E22324566643

- MarcassaCFaggianoPGrecoCA retrospective multicenter study on long-term prevalence of persistent pain after cardiac surgeryJ Cardiovasc Med201516768774

- BjornnesAKParryMLieIPain experiences of men and women after cardiac surgeryJ Clin Nurs2016253058306827301786

- GjeiloKHKlepstadPWahbaAPersistent pain after cardiac surgery: a prospective studyActa Anaesthesiol Scand201054707819681771

- AbrishamiAChanJChungFPreoperative pain sensitivity and its correlation with postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic reviewAnesthesiology201111444545721245740

- RuscheweyhRMarziniakMStumpenhorstFPain sensitivity can be assessed by self-rating: development and validation of the Pain Sensitivity QuestionnairePain2009146657419665301

- ValebergBTPedersenLMGirottoVValidation of the Norwegian Pain Sensitivity QuestionnaireJ Pain Res2017101137114228553134

- RuscheweyhRVerneuerBDanyKValidation of the pain sensitivity questionnaire in persistent pain patientsPain20121531210121822541722

- LarssonBGerdleBBjorkJPain sensitivity and its relation to spreading on the body, intensity, frequency, and duration of pain: a cross-sectional population-based study (SwePain)Clin J Pain20173357958727648588

- SellersABRuscheweyhRKelleyBJValidation of the English language pain sensitivity questionnaireReg Anesth Pain Med20133850851424141873

- HermesdorfMBergerKBauneBTPain sensitivity in patients with major depression: differential effect of pain sensitivity measures, somatic cofactors, and disease characteristicsJ Pain20161760661626867484

- KimHJRuscheweyhRYeoJHTranslation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validity of the Korean version of the pain sensitivity questionnaire in persistent pain patientsPain Pract20141474575124131768

- RuscheweyhRViehoffATioJPsychophysical and psychological predictors of acute pain after breast surgery differ in patients with and without pre-existing persistent painPain20171581030103828195858

- RehbergBMathivonSCombescureCPrediction of acute postoperative pain following breast cancer surgery using the Pain Sensitivity Qestionnaire: a cohort studyClin J Pain201733576627922844

- DuchowJSchlörickeEHüppeMSelbstbeurteilte Schmerzempfind-lichkeit und postoperativer Schmerz [Self-rated pain sensitiviety and postoperative pain]Der Schmerz201327371379 German [with English abstract]23860632

- KimHJLeeJIKangKTInfluence of pain sensitivity on surgical outcomes after lumbar spine surgery in patients with lumbar spinal stenosisSpine20154019320025384051

- AzimiPBenzelECCut-off value for pain sensitivity questionnaire in predicting surgical success in patients with lumbar disc herniationPLoS One201611e016054127494617

- ValebergBTHovikLHGjeiloKHRelationship between self-reported pain sensitivity and pain after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective study of 71 patients 8 weeks after a standardized fast-track programJ Pain Res2016962562927660489

- BjornnesAKParryMLieIThe impact of an educational pain management booklet intervention on postoperative pain control after cardiac surgeryEur J Cardiovasc Nurs201716182726846145

- SanghaOStuckiGLiangMHThe Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services researchArthritis Rheum20034915616312687505

- CleelandCSRyanKMPain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain InventoryAnn Acad Med Singapore1994231291388080219

- GjeiloKHStensethRWahbaAValidation of the brief pain inventory in patients six months after cardiac surgeryJ Pain Symptom Manage20073464865617629665

- FitzmauriceGMLairdNMWareJHApplied Longitudinal Analysis2nd edChichesterWiley2011

- StataCorpLPStata statistical software: release 13College Station, TXStataCorp LP2013

- BjornnesAKParryMLieIThe association between hope, marital status, depression and persistent pain in men and women following cardiac surgeryBMC Womens Health201818229291728

- BjornnesAKRustoenTLieIPain characteristics and analgesic intake before and following cardiac surgeryEur J Cardiovasc Nurs201615475425192967

- DeJeanDGiacominiMVanstoneMPatient experiences of depression and anxiety with persistent disease: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesisOnt Health Technol Assess Ser201313133

- RuscheweyhRDanyKMarziniakMBasal pain sensitivity does not predict the outcome of multidisciplinary persistent pain treatmentPain Med2015161635164225801234

- QuanXFongDYTLeungAYMValidation of the Mandarin Chinese Version of the Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire (PSQ)Pain Pract Epub201766

- AzimiPAzhariSShahzadiSOutcome measure of pain in patients with lumbar disc herniation: validation study of the Iranian version of Pain Sensitivity QuestionnaireAsian Spine J20161048048727340527

- BellBARuscheweyhRKelleyBJEthnic differences identified by Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire correlate with clinical pain responsesReg Anesth Pain Med20184320020429278602