Abstract

Background

Gout, a common medical condition that causes pain, can be treated by painkillers and anti-inflammatories. Indometacin and etoricoxib are two such drugs. However, no synthesized evidence exists comparing etoricoxib with indometacin in treating patients with gout.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and the Cochrane Library without restrictions on language or publication date for potential randomized clinical trials comparing etoricoxib with indometacin for gout. The meta-analysis was conducted using a random-effects model.

Results

Search results yielded 313 references from six electronic databases, four of which met the eligibility criteria. These four were randomized clinical trials, and they involved a total of 609 patients with gouty arthritis. No significant differences were observed in pain score change, tenderness, or swelling between etoricoxib and indometacin; the mean differences were −0.05 (95% CI, −0.21 to 0.10), −0.06 (95% CI, −0.18 to 0.05), and −0.04 (95% CI, −0.17 to 0.09). However, the pooled data revealed that significantly fewer overall adverse events occurred in the etoricoxib group (n=105, 33.5%) than in the indometacin group (n=130, 44.1%) and the risk ratio was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.62–0.94).

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis revealed that etoricoxib and indometacin have similar effects on pain relief. However, etoricoxib has a significantly lower risk of adverse events than does indometacin, especially digestive system-related adverse events.

Keywords:

Introduction

Gout is a common medical problem that mainly affects middle-aged men,Citation1 with a peak incidence in the fifth decade of life.Citation2 The prevalence of gout increases among postmenopausal women with diuretic-treated hypertension and renal insufficiency.Citation3 Risk factors for gout include obesity, alcohol intake, diuretic use, a diet rich in meat, seafood, or high-fructose food or drink intake, and poor kidney function.Citation4–Citation7 Furthermore, an increased risk of cardiac disease in patients with gout was observed and this risk is above and beyond that contributed by the traditional risk factors for heart disease.Citation8,Citation9 Gouty arthritis not only contributes to heart disease but also directly influences the quality of life. Acute gouty arthritis often peaks within 24 hours of onset with a very painful, warm, tender, and swollen joint, and it commonly affects the joints of the lower extremity, particularly the metatarsophalangeal joint.Citation10,Citation11 According to the 2012 American College of Rheumatology Guidelines for Management of Gout,Citation12 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), corticosteroids, or oral colchicine are appropriate first-line options for the treatment of acute gout and certain combinations can be used for severe or refractory attacks. They suggest the use of the NSAIDs, such as naproxen, indometacin, and sulindac, for the treatment of acute gout. However, nonselective NSAIDs, which inhibit both cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2, are associated with dyspepsia and potential gastrointestinal (GI) perforations, ulcers, and bleeding.Citation13,Citation14 Etoricoxib, a highly selective COX-2 inhibitor, has demonstrated anti-inflammation, analgesic, and antipyretic properties and reduces the incidence of GI-related adverse events, compared with nonselective NSAIDs.Citation15–Citation18 Besides, the cardiovascular safety of COX-2 inhibitor has been revealed.Citation19 Indometacin is the most potent inhibitor of nonselective NSAIDs, although a more potent inhibitor of COX-1 than that of COX-2.Citation20 We performed a systemic review and meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of etoricoxib and indometacin in the treatment of acute gout.

Methods

Search and study selection

Relevant research articles comparing etoricoxib and indometacin in patients with gouty arthritis were searched by using the following relative terms in PubMed, Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and the Cochrane Library: “gout”, “gouty”, “gouty arthritis”, “uric arthritis”, “arthralgia”, “Etoricoxib”, and “indometacin”. The systematic literature search using free-text, medical subject headings (MeSH and Emtree), and Boolean algebras was conducted by two authors to identify citation records without language or publication date restrictions from inception till July 19, 2018 (Table S1).

The two authors screened the returned citations imported into EndNote (Version X7) for Microsoft Windows. End-Note systematically removed duplications. The authors completed further categorizations and duplications manually. The inclusion criteria in the title and abstract screening phase were as follows: 1) studies involving patients with gout and 2) studies directly comparing etoricoxib and indometacin. The exclusion criteria in the subsequent full-text screening phase were as follows: 1) studies investigating combined therapy, 2) studies not involving a randomized controlled trial (RCT), and 3) articles not reporting a complete study (conference report and relevant documents). The first author (TML) participated in the screening task in case of any disagreement regarding screening categorization between the two authors.

Outcomes assessment

This systematic review and meta-analysis conducted outcomes of effects and safety between etoricoxib and indometacin. The outcomes of effects included tenderness, swelling, global assessments, and pain score. There were two parts in global assessments that consisted of patient’s assessment and investigator’s assessment. The pain score was measured by VAS. The safety outcomes included adverse events that analyzed with subgroup analysis according to systems.

Quality assessment

This systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the risk of bias by using the appraisal tools of the Risk of Bias Tool of Cochrane. The tool comprises the following items: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. These eight items in the appraisal tool addresses six categories of bias, namely selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other bias. Two authors (T-ML and J-EC) individually assessed the included RCTs. The author (Y-NK) participated in the appraisal work in case of any disagreement regarding screening categorization between the two authors.

Data extraction and analysis

Two authors independently performed data extraction. They not only identified relevant data but also double-checked the meaning of the data and converted the data for appropriate pooling analysis. If the included articles reported mean and standard error (SE) without SD, the authors estimated the SD on the basis of the included sample size (SE = SD/√N). If the included study reported median values with minimum and maximum only, the authors estimated the mean and SD values from the sample size, median, and range.Citation21

Peto ORs were calculated when dichotomous data involved zero cells. Mean differences (MDs) of the original studies pooled in a random-effects model were used to compare continuous variables measured using the same tool and conditions between etoricoxib and indometacin. I2 obtained from each meta-analysis was used for estimating the heterogeneity among the included studies. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 for all analyses. I2 of the pooled studies was represented using the percentage of total variability across the studies. I2 values 25, 50, and 75% were considered to indicate low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.Citation22 Data were expressed as risk ratios with 95% CI, and I2 was calculated and presented in a forest plot and analyzed using the RevMan software (Version 5.3) for Microsoft Windows. Small study bias was detected by using funnel plot with Egger’s regression intercept. The systematic review and results of meta-analysis are reported according to the PRISMA guidelines.Citation23

Results

Literature search and selection

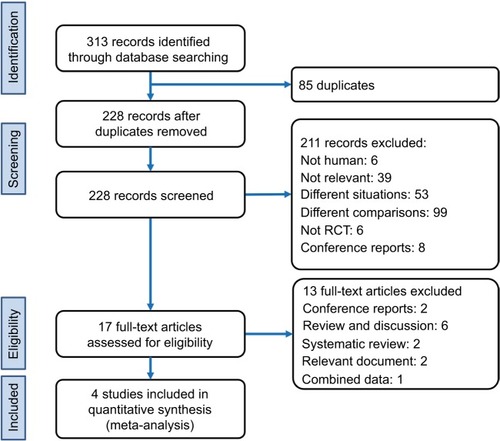

The search returned 313 records, of which 13 citations were from PubMed, 99 citations were from Embase, 123 citations were from Ovid MEDLINE, 33 citations were from ScienceDirect, 32 citations were from Web of Science, and 13 citations were from the Cochrane Library. Of these, 85 citations were duplicated. According to the exclusion criteria, 211 citations were excluded after title and abstract screening. In the full-text screening phase, 13 non-RCTs and conference reports were excluded. The literature identification and study selection process are presented in .

Characteristics of included studies

The four RCTs included in this synthesis randomized 609 patients, with 14 patients lost to follow-up.Citation24–Citation27 lists the study characteristics including trial location, inclusion years, sample size, patients’ age, sex, disease classification, and index joint, and loss to follow-up. These studies spanned approximately 15 years from 2002 to 2016 and involved Africa, America, and Asia. Most of the included patients were men. presents the individual quality of the included studies. In summary, the quality of the studies was acceptable, except for the reporting bias item. The four RCTs had a high risk of bias (25%) in terms of allocation generation, allocation concealment, blinding, and incomplete outcome data. However, the risk of reporting bias was high (Figure S1).

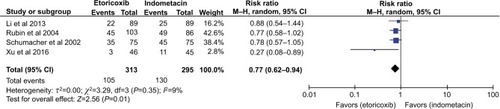

Figure 2 Forest plot of meta-analysis for overall adverse events between etoricoxib and indometacin.

Table 1 Characteristics of included RCTs

Effect outcomes

The effects of etoricoxib and indometacin on gouty arthritis are presented in . In two included studies with 363 patients with acute gouty arthritis,Citation24,Citation25 the presented evidence revealed no significant differences in pain score change in days 2–5 and days 2–8 between etoricoxib and indometacin and the MDs were –0.05 (95% CI, –0.21 to 0.10; P>0.05) and –0.05 (95% CI, −0.20 to 0.10; P>0.05) (Figure S2). These two analyses were conducted with low heterogeneity (I2=0%; P>0.05). Three trials reported the effect of the two medications on tenderness.Citation24–Citation26 The pooled data of 510 patients revealed no significant difference in tenderness between etoricoxib and indometacin (MD =−0.06; 95% CI, −0.18 to 0.05; P>0.05) (Figure S3). Three of the four included RCTs reported information on swelling.Citation24–Citation26 The meta-analysis based on data from 510 patients showed no significant difference between etoricoxib and indometacin (MD =−0.04; 95% CI, −0.17 to 0.09; P>0.05) (Figure S4). Moreover, the pooled data of three RCTs with 505 patients revealed no significant difference in the patient’s global assessment between the two drugs (MD =−0.09; 95% CI, −0.25 to 0.06; P>0.05) (Figure S5)Citation24–Citation26 and the meta-analysis of three RCTs with 507 patients also indicated no statistical difference in the investigator’s global assessment between the drugs (MD =−0.11; 95% CI, −0.22 to 0.01; P<0.05) (Figure S6).Citation24–Citation26 Low heterogeneity (I2=0%; P>0.05) was found in all the meta-analyses of effect outcomes.

Table 2 Effect outcome summary

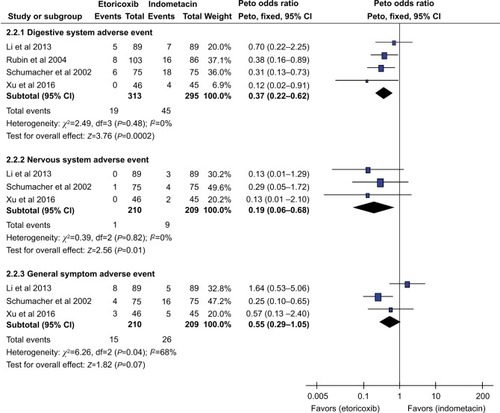

Safety outcomes

Four RCTs reported adverse events.Citation24–Citation27 The pooled data of 608 patients revealed that fewer overall adverse events occurred in the etoricoxib group (n=105, 33.5%) than in the indometacin group (n=130, 44.1%) with significance, and the risk ratio was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.62–0.94; P<0.05) (). The heterogeneity of this pooled analysis was also low (I2=9%; P>0.05). Sensitivity analysis showed that trend of the result was not changed when any included RCT was removed from the meta-analysis (Figure S7). The Egger’s test (t=1.523; 95% CI, −6.211 to 2.963; P=0.267) did not detect small study bias in this result (Figure S8).

According to the available data, this systematic review identified adverse events of the digestive system, nervous system, and general symptoms. Data on adverse events of the respiratory system, cardiovascular system, and severe adverse events were insufficient to conduct a meta-analysis. The adverse events of the digestive system include abdominal distention, gastrectasia, diarrhea, stomach upset, stomachache, digestive tract upset, nausea, vomiting, and dry mouth. The nervous system adverse events were somnolence and hand numbness. The general symptoms were dizziness, vertigo, chills, fever, pedal edema, and headache. The pooled data of four RCTs with 608 patients revealed that the etoricoxib group (n=19, 6.1%) had fewer digestive system adverse events than the indometacin group (n=45, 15.3%), with the Peto OR being 0.37 (95% CI, 0.22–0.62; P<0.05) (, 2.2.1).Citation24–Citation27 Three of the included four RCTs reported information on nervous system adverse events.Citation24,Citation26,Citation27 The evidence revealed that the etoricoxib group (n=1, 0.5%) had fewer nervous system adverse events than the indometacin group (n=9, 4.3%), with the Peto OR being 0.19 (95% CI, 0.06–0.68; P<0.05) (, 2.2.2).Citation24,Citation26,Citation27 However, the meta-analysis of the three RCTs with 419 patients indicated no difference in general symptoms between the two groups, with the Peto OR being 0.55 (95% CI, 0.29–1.05; P>0.05) (, 2.2.3).Citation24–Citation26

Discussion

Contribution of etoricoxib to gout

Acute gouty arthritis is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis. Prostaglandins play a major role in the process of inflammatory response. They are derived from arachidonic acid through the action of COX isoenzymes. COX-1 is constitutively expressed in most cells and is responsible for homeostatic functions, which include epithelial cytoprotection, platelet aggregation, and renal blood flow regulation.Citation28 COX-2, induced by inflammatory stimuli, is the dominant source of prostaglandins in inflammation.Citation28,Citation29 Human data indicate that COX-1-derived prostanoids drive the initial phase of inflammation, whereas COX-2 upregulation occurs several hours later.Citation30–Citation32 Both COX-1 and COX-2 are involved in the process of acute inflammation; moreover, our study revealed comparable effects of etoricoxib and indometacin on gouty arthritis.

In the analyzed studies, digestive tract upset was the most common complication in patients under treatment with either etoricoxib or indometacin. NSAID-induced injuries to the GI tract ranging from petechia to ulcers were not rarely observed. They disrupted the mucosa of the GI tract, causing bleeding, perforation, or obstruction.Citation33 NSAID-induced ulcerative lesions of the stomach predominantly result from systemic effects associated with the mucosa and topical injury to the mucosa. In systemic effects, COX inhibition was reported to lead to platelet inhibition and prostanoid depletion.Citation33 When platelets are inhibited, gastric ulcer healing may be influenced through altering the ability of releasing growth factors such as EGF and vascular endothelial growth factor.Citation34,Citation35 Hence, inhibition with selective COX-2 inhibitors may be safer in the GI tract and in platelets.Citation36 In the RCTs analyzed in this systematic review,Citation24–Citation27 the incidence of the adverse events of the digestive system was significantly lower in patients taking etoricoxib than in those taking indometacin, a finding that is consistent with the aforementioned results. Additionally, recent results have revealed that both COX isozymes may be a source of cytoprotective prostanoids for inhibiting COX-1 and upregulating COX-2 expression, despite the possible existence of subsequent deleterious effects such as gastric hypermotility.Citation37 Hence, inhibition of both COX-1 and COX-2 may increase the risk of gastric lesion formation.Citation37

PGE2 and PGI2 are the main protective prostaglandins. Inhibiting them by using NSAIDs may decrease the stimulation of the synthesis and secretion of mucus and bicarbonate and reduce mucosal blood flow and epithelial proliferation, resulting in tropical injury of the stomach mucosa, thus making it susceptible to endogenous and exogenous factors such as acid and Helicobacter pylori infection.Citation33 In addition, NSAIDs that are weak acids may cause topical damage of the epithelium at the site of the GI mucosa, according to the hypothesis that NSAIDs would compromise the extracellular zwitterionic phospholipid hydrophobic surface barrier of the stomach to luminal acid.Citation38

The perfusion of the luminal surface of the stomach is essential for mucosal integrity.Citation33 When focal gastric mucosal blood flow decreases, the mucosa becomes more susceptible and NSAID-induced injuries such as hemorrhagic foci and ulceration may occur at the focal ischemic patch.Citation39 PGE2 and PGI2 are vasodilators, and inhibiting their synthesis is likely to cause focal ischemia; however, selective COX-2 NSAIDs do not reduce gastric mucosa blood flow.Citation40,Citation41 Inhibiting TXA2 production through platelet COX-1 inhibition increases the bleeding tendency when an active GI bleeding site is present.Citation42 Most (86%) of the NSAIDs’ GI effects are in the upper GI tract.Citation43 One effective strategy for managing NSAID-GI bleeding is proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). The PPI strategy for NSAID-GI risk reduction is that this approach covers the proportion of events occurring only in the upper GI tractCitation44 and it can significantly reduce the risk of upper GI bleeding.Citation45 Moreover, leukocytes may be one of the factors in the pathogenesis of NSAID-induced gastric ulceration. NSAIDs such as indometacin are potent promoters of leukocytes, particularly neutrophils, and adhere to the vascular endothelium within GI microcirculation, leading to mucosal injury.Citation46,Citation47

In the small intestine, topical damage engendered by NSAIDs plays a key role in the pathogenesis of intestinal injury; it could be concluded that the intensity of the intraluminal mucosal injury is related to the duration for which the epithelium has been exposed to these drugs and enterohepatic circulation contributes extensively to this process.Citation33

Adverse events in renal function are also noteworthy. Both COX-1 and COX-2 are expressed in the kidneys. Inhibition of the renal prostaglandin E2 can result in the sodium retention and edema and exacerbation of hypertension. Inhibition of prostacyclin expression can reduce renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate.Citation48

Strengths, limitations, and implications for future research

The present study has more advantages than published systematic reviews and meta-analyses.Citation49,Citation50 The advantages of this systematic review and meta-analysis are as follows: 1) a more specific pharmacological comparison was conducted between etoricoxib and indometacin, which are the most potent inhibitors of nonselective NSAIDs; 2) a new RCT was involved; 3) a more meaningful subgroup analysis on complications was conducted; and 4) a modified statistical method of Peto ORs was used when dichotomous data indicated zero cells. Therefore, the present findings may be more reliable than those of previous meta-analyses.

Despite its advantages, the present meta-analysis has some limitations. Although our meta-analysis exhibited low heterogeneity, some limitations may be reflected in the characteristics of the included RCTs. First, the population in the four included RCTs was predominantly male. Therefore, the results of the present meta-analysis may not satisfactorily represent the female population. Second, disease classification and index joint may influence drug effects. However, the present meta-analysis cannot separately access the data according to disease classification and index joint. The present meta-analysis could provide only an overview of the comparison of the effects and safety of etoricoxib and indometacin. Future research must determine the effects and safety of the two drugs by considering different sexes, disease classification, and index joint. A well-designed RCT or meta-analysis of individual patient data may be warranted in the future. Third, PPI is recommended to prevent NSAID-GI bleeding, but the RCTs we included in this systematic review and meta-analysis did not reported any PPI usage. Thus, the combined effect of PPI and the two drugs should be investigated in further trials. Moreover, the present meta-analysis cannot assess publication bias. Because all of the outcomes pooled from only four RCTs, this meta-analysis cannot constructed meaningful funnel plots for publication bias assessment.Citation51

Conclusion

From our meta-analysis, we found that etoricoxib has more favorable trend than indometacin in providing pain relief in acute gouty arthritis. Moreover, etoricoxib has a significantly lower risk of adverse events than indometacin, particularly for digestive system adverse effects. The effects of etoricoxib and indometacin among all the medications including interleukin-1 inhibitors, colchicine, and glucocorticoids should be investigated in future studies.

Author contributions

TML designed the study, identified evidence systematically, critically appraised the included articles, interpreted the result of analysis, and drafted the first version of manuscript. JEC identified evidence systematically, critically appraised the included articles, acquired the data, managed data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. CCC interpreted the result of analysis, critically reviewed the manuscript, and supervised research. YNK proposed the study, analyzed the data, acquired the data, interpreted the result of analysis, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KramerHMCurhanGThe association between gout and nephrolithiasis: the national health and nutrition examination survey III, 1988–1994Am J Kidney Dis2002401374212087559

- HarrisMDSiegelLBAllowayJAGout and hyperuricemiaAm Fam Physician199959492593410068714

- García-MéndezSBeas-IxtláhuacEHernández-CuevasCFemale gout: age and duration of the disease determine clinical presentationJ Clin Rheumatol201218524224522832306

- ChoiHKAtkinsonKKarlsonEWCurhanGObesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up studyArch Intern Med2005165774274815824292

- ChoiHKAtkinsonKKarlsonEWWillettWCurhanGAlcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective studyLancet200436394171277128115094272

- ChoiHKAtkinsonKKarlsonEWWillettWCurhanGPurine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in menN Engl J Med2004350111093110315014182

- KrishnanEChronic kidney disease and the risk of incident gout among middle-aged men: a seven-year prospective observational studyArthritis Rheum201365123271327823982888

- FeigDIKangDHJohnsonRJUric acid and cardiovascular riskN Engl J Med2008359171811182118946066

- SinghJAWhen gout goes to the heart: does gout equal a cardiovascular disease risk factor?Ann Rheum Dis201574463163425603830

- BeckerMAClinical aspects of monosodium urate monohydrate crystal deposition disease (gout)Rheum Dis Clin North Am19881423773943051156

- FamAGGout in the elderly. Clinical presentation and treatmentDrugs Aging19981332292439789727

- KhannaDKhannaPPFitzgeraldJD2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritisArthritis Care Res2012641014471461

- EmmersonBTThe management of goutN Engl J Med199633474454518552148

- WallaceSLSingerJZTherapy in goutRheum Dis Clin North Am19881424414573051159

- EhrichEWDallobAde LepeleireICharacterization of rofecoxib as a cyclooxygenase-2 isoform inhibitor and demonstration of analgesia in the dental pain modelClin Pharmacol Ther199965333634710096266

- EhrichEWSchnitzerTJMcIlwainHEffect of specific COX-2 inhibition in osteoarthritis of the knee: a 6 week double blind, placebo controlled pilot study of rofecoxib. Rofecoxib Osteoarthritis Pilot Study GroupJ Rheumatol199926112438244710555907

- LangmanMJJensenDMWatsonDJAdverse upper gastrointestinal effects of rofecoxib compared with NSAIDsJAMA1999282201929193310580458

- SimonLSWeaverALGrahamDYAnti-inflammatory and upper gastrointestinal effects of celecoxib in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trialJAMA1999282201921192810580457

- DognéJMSupuranCTPraticoDAdverse cardiovascular effects of the coxibsJ Med Chem20054872251225715801815

- MitchellJAAkarasereenontPThiemermannCFlowerRJVaneJRSelectivity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs as inhibitors of constitutive and inducible cyclooxygenaseProc Natl Acad Sci U S A1993902411693116978265610

- HozoSPDjulbegovicBHozoIEstimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sampleBMC Med Res Methodol200551315840177

- HigginsJPThompsonSGDeeksJJAltmanDGMeasuring inconsistency in meta-analysesBMJ2003327741455756012958120

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGPRISMA GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementBMJ200967e1000097

- LiTChenSLDaiQEtoricoxib versus indometacin in the treatment of Chinese patients with acute gouty arthritis: a randomized double-blind trialChin Med J2013126101867187123673101

- RubinBRBurtonRNavarraSEfficacy and safety profile of treatment with etoricoxib 120 mg once daily compared with indomethacin 50 mg three times daily in acute gout: a randomized controlled trialArthritis Rheum200450259860614872504

- SchumacherHRBoiceJADaikhDIRandomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritisBMJ200232473521488149212077033

- XuLLiuSGuanMXueYComparison of prednisolone, etoricoxib, and indomethacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis: an ppen-label, randomized, controlled trialMed Sci Monit20162281081726965791

- DuboisRNAbramsonSBCroffordLCyclooxygenase in biology and diseaseFaseb J19981212106310739737710

- CronsteinBNTerkeltaubRThe inflammatory process of gout and its treatmentArthritis Res Ther20068Suppl 1S3

- RicciottiEFitzgeraldGAProstaglandins and inflammationArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol2011315986100021508345

- Schjerning OlsenAMFosbølELLindhardsenJDuration of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and impact on risk of death and recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with prior myocardial infarction: a nationwide cohort studyCirculation2011123202226223521555710

- SmythEMGrosserTWangMYuYFitzgeraldGAProstanoids in health and diseaseJ Lipid Res200950SupplS423S42819095631

- PatrignaniPTacconelliSBrunoASostresCLanasAManaging the adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugsExpert Rev Clin Pharmacol20114560562122114888

- MaLElliottSNCirinoGBuretAIgnarroLJWallaceJLPlatelets modulate gastric ulcer healing: role of endostatin and vascular endothelial growth factor releaseProc Natl Acad Sci U S A200198116470647511353854

- TarnawskiASzaboILHusainSSSoreghanBRegeneration of gastric mucosa during ulcer healing is triggered by growth factors and signal transduction pathwaysJ Physiol Paris2001951–633734411595458

- FitzgeraldGACOX-2 and beyond: Approaches to prostaglandin inhibition in human diseaseNat Rev Drug Discov200321187989014668809

- TanakaAArakiHKomoikeYHaseSTakeuchiKInhibition of both COX-1 and COX-2 is required for development of gastric damage in response to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugsJ Physiol Paris2001951–6212711595414

- LichtenbergerLMWhere is the evidence that cyclooxygenase inhibition is the primary cause of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced gastrointestinal injury? Topical injury revisitedBiochem Pharmacol200161663163711266647

- GanaTJHuhlewychRKooJFocal gastric mucosal blood flow in aspirin-induced ulcerationAnn Surg198720543994033566377

- WallaceJLCirinoGThe development of gastrointestinal-sparing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugsTrends Pharmacol Sci199415114054067855901

- WallaceJLMcKnightWReuterBKVergnolleNNSAID-induced gastric damage in rats: requirement for inhibition of both cyclooxygenase 1 and 2Gastroenterology2000119370671410982765

- LanasAScheimanJLow-dose aspirin and upper gastrointestinal damage: epidemiology, prevention and treatmentCurr Med Res Opin200723116317317257477

- LanasAPerez-AisaMAFeuFA nationwide study of mortality associated with hospital admission due to severe gastrointestinal events and those associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug useAm J Gastroenterol200510081685169316086703

- CryerBNSAID-associated deaths: the rise and fall of NSAID-associated GI mortalityAm J Gastroenterol200510081694169516144121

- LanasAGarcía-RodríguezLAArroyoMTRisk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer bleeding associated with selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, traditional non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin and combinationsGut200655121731173816687434

- AsakoHKubesPWallaceJGaginellaTWolfREGrangerDNIndomethacin-induced leukocyte adhesion in mesenteric venules: role of lipoxygenase productsAm J Physiol19922625 Pt 1G903G9081317111

- AsakoHKubesPWallaceJWolfREGrangerDNModulation of leukocyte adhesion in rat mesenteric venules by aspirin and salicylateGastroenterology199210311461521319367

- CronsteinBNSunkureddiPMechanistic aspects of inflammation and clinical management of inflammation in acute gouty arthritisJ Clin Rheumatol201319112923319016

- van DurmeCMWechalekarMDBuchbinderRSchlesingerNvan der HeijdeDLandewéRBNon-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute goutCochrane Database Syst Rev20149CD010120

- ZhangSZhangYLiuPZhangWMaJLWangJEfficacy and safety of etoricoxib compared with NSAIDs in acute gout: a systematic review and a meta-analysisClin Rheumatol201635115115826099603

- SterneJASuttonAJIoannidisJPRecommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trialsBMJ2011343d400221784880