Abstract

Background

The influence of work-related fear-avoidance on pain and function has been consistently reported for patients with musculoskeletal low back pain. Emerging evidence suggests similar influences exist for other anatomical locations of musculoskeletal pain, such as the cervical spine and extremities. However, research is limited in comparing work-related fear-avoidance and associations with clinical outcomes across different anatomical locations. The purpose of this study was to examine the associations between work-related fear-avoidance, gender, and clinical outcomes across four different musculoskeletal pain locations for patients being treated in an outpatient physical therapy setting.

Methods

This study was a secondary analysis of data obtained prospectively from a cohort of 313 participants receiving physical therapy from an outpatient clinic.

Results

No interaction was found between gender and anatomical location of musculoskeletal pain on work-related fear-avoidance scores. Work-related fear-avoidance scores were higher in the cervical group versus the lower extremity group; however, there were no other differences across anatomical locations. Work-related fear-avoidance influenced intake pain intensity in patients with spine pain but not extremity pain. Conversely, work-related fear-avoidance influenced intake function for participants with extremity pain but not spine pain. Similar results were observed for change scores, with higher work-related fear-avoidance being associated with more, not less, change in pain and function for certain anatomical locations.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that work-related fear-avoidance is similar for patients experiencing musculoskeletal pain. However, associations between work-related fear-avoidance and clinical outcomes may differ based on the anatomical location of that pain. Further, increased work-related fear-avoidance may not be indicative of poor clinical outcomes for this type of patient population.

Introduction

A critical analysis reported that, in working populations, psychological distress related to low back injury is associated with the persistence of disability, return to work status, and financial burden.Citation1 A psychological factor that appears particularly influential is work-related fear-avoidance, whereby an individual exhibits pain-related fear specific to their work beliefs. Relationships between work-related fear-avoidance and clinical outcomes like pain and function are routinely reported for patients experiencing low back pain. Specifically, work-related fear-avoidance beliefs have been found to be predictive of disability,Citation2–Citation4 work-related physical capacity,Citation5 and return to work status,Citation2,Citation6,Citation7 for patients with low back pain.

The larger body of knowledge in work-related fear-avoidance pertains to low back pain versus other anatomical locations with musculoskeletal pain (eg, neck pain, extremity pain). This may be partially attributed to frequent use of the low back for validation of fear-avoidance theory Citation8–Citation10 and development of fear-avoidance measures.Citation11 Nevertheless, emerging evidence suggests that the importance of work-related fear-avoidance may not be exclusive to this anatomical location. Studies analyzing the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire work subscale scoresCitation12 and individual Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire work-subscale screening itemsCitation13 have found no difference in work beliefs for other anatomical locations when compared with the lumbar spine. Further, work-related fear-avoidance beliefs have been associated with pain and disability for patients with other disorders such as mechanical neck painCitation14 and patellofemoral pain.Citation15

However, questions remain as to the capacity of work-related fear-avoidance to affect different anatomical locations. For example, research is limited on comparing the strength of association of work-related fear-avoidance with clinical outcomes across multiple pain locations. George et alCitation12 compared fear-avoidance beliefs in patients with neck pain versus low back pain and, although similar raw work-related fear-avoidance scores by anatomy were reported, a stronger association between work-related fear-avoidance and disability existed in the low back pain cohort. Another issue may be the existence of a gender difference in fear-avoidance beliefs across anatomical locations. Research has suggested that males with neck or low back pain have potential for higher work-related fear-avoidance beliefs compared with females.Citation11,Citation12,Citation16 Additionally, association between pain-related psychological constructs (eg, anxiety) and pain reports have been reported to be stronger in males.Citation17

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine work-related fear-avoidance beliefs across four different anatomical locations with musculoskeletal pain for patients being treated in an outpatient physical therapy setting. The first aim was to determine whether work-related fear-avoidance differed across cervical, upper extremity, lumbar, and lower extremity locations and analyze potential associations between work-related fear-avoidance beliefs and gender for these anatomical locations. It was hypothesized that (1) consistent with other work in this area,Citation12,Citation13 raw scores for fear-avoidance beliefs about work would be similar regardless of anatomical location and (2), consistent with other work in this area,Citation11,Citation12,Citation16 males would report higher levels of work-related fear-avoidance than females across anatomical locations. The second aim was to examine whether work-related fear-avoidance had similar influence by anatomical location on pain intensity and function. It was hypothesized that after controlling for selected demographic factors including gender, patients with low back pain would have a stronger relationship between work-related fear-avoidance, pain intensity, and function levels (at intake and represented in change scores), compared with patients with musculoskeletal pain in other anatomical locations. The second aim provided data to determine if findings from a previous cross-sectional studyCitation12 were consistent with this longitudinal study.

Methods

Study design

This was a secondary analysis of data from a prospective cohort studyCitation18 of patients receiving physical therapy for musculoskeletal pain from an outpatient physical therapy clinic. Included in the current analyses are selected data from intake (work-related fear-avoidance, pain intensity, and function) and discharge (pain intensity and function) assessments.

Patients

A consecutive sample of patients receiving outpatient physical therapy from an outpatient physical therapy clinic in Portland, Oregon, from February 2009 to June 2010 contributed data to this study. Criteria for inclusion in the original prospective study were: being able to both read and speak the English language (for filling out assessment measurements); the existence of musculoskeletal pain, serving as the primary motive for seeking out physical therapy services; successful completion of intake and discharge assessment measurements; and completion of physical therapy services by scheduled completion date of data collection (June 1, 2010).Citation18 Criteria for exclusion from the study were: if pain complaints were deemed non-musculoskeletal in origin by the physical therapist; if the patient had multiple sites of musculoskeletal pain (eg, having both neck and low back pain); or if the patient had no pain at the beginning of the study. Data were collected during routine clinical encounters and de-identified before analysis. As such, this study qualified as exempt by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board and patients were not required to provide informed consent.

Measures

Clinical

Age, gender, symptom duration, and anatomical location information was collected at intake. Symptom duration was defined as the number of days from the onset of symptoms until the patient started physical therapy. Anatomical location of pain was determined by primary patient complaint, which was verified upon initial examination by the physical therapist. Anatomical location of musculoskeletal pain was then collapsed into one of four areas for the purpose of the current analysis: cervical, upper extremity, lumbar, or lower extremity. The authors have used similar approaches for differentiating anatomical location in their previous studies of depressive symptomsCitation19 and fear-avoidance of physical activity.Citation18

Fear-avoidance beliefs

The Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) was completed during intake. The work subscale (FABQ-W) was the sole fear-avoidance measure included in this analysis as data from the physical activity scale (FABQ-PA) have been previously reported.Citation18 The FABQ-W comprise seven items that are scored on a seven-point Likert scale. Answers range from “completely disagree” to “completely agree,” with a total score ranging from 0 to 42. Larger scores on the FABQ-W are indicative of higher levels of work-related fear-avoidance. The FABQ-W was originally intended for patients with low back pain,Citation11 and requires slight semantic modification to allow for use in other anatomical locations. An example is replacing five instances of the word “back” on the FABQ-W to “neck” to use in the neck pain cohort. Validation of the modified FABQ-W was not part of this analysis, however prior modification of the FABQ has been shown to have ample predictive validity in previous studies involving musculoskeletal pain.Citation11,Citation14,Citation15,Citation18,Citation20

Pain intensity

Patients completed a visual analog scale (VAS) at intake and discharge. The VAS was implemented to measure pain intensity, which has been found to be a valid and reliable measure of musculoskeletal pain.Citation21 The VAS consists of a 10 cm line anchored by “no pain” and “worst pain imaginable,” with participants drawing through the line to indicate present level of pain intensity. The distance the patient marked from the “no pain” anchor was measured and reported as pain intensity to one decimal point.

Function

The CareConnections Functional Outcomes Index (CCFOI)Citation22 (formerly Therapeutic Associates Outcomes System [TAOS]) was used to obtain a self-reported measure of function. It combines five functional activities specific to anatomical location of pain (concentration, headaches, reading, driving, and lifting for cervical spine pain) with five functional activities independent of anatomical location (walking, work, personal care, sleeping, and recreational activities). Functional activities are rated on a scale of 0 (lowest level of function) to 5 (highest level of function). A score for the CCFOI is derived by adding scores for all activities. The final score is reported as a percentage from 0% to 100%. Currently, there is limited psychometric information pertaining to this measure.Citation23 However, the CCFOI was deemed to have face validity and appears responsive based on previous analysis with the FABQ-PA.Citation18

Physical therapy practice

The clinic used for data collection is an outpatient setting specializing in orthopedic manual physical therapy. Four physical therapists were involved in the study (one male, three females). Physical therapists were either fellowship trained or enrolled in an orthopedic manual therapy fellowship program, with the exception of one physical therapist who was preparing for entrance into a fellowship program. One physical therapist was an orthopedic certified specialist through the American Physical Therapy Association. Average clinical experience was 5.8 years (range = 1–13 years).

Patient treatment

Patient treatment was not a primary focus of this analysis and is therefore only summarized. A more thorough description of treatment is provided in a recent study that utilized the same patient cohort.Citation18 Prior to receiving the scored FABQ-W from patients, physical therapists were given information regarding the Fear-Avoidance Model and how to interpret FABQ-W scores. Physical therapists were instructed to provide treatment as they normally would for musculoskeletal cases. However, therapists were encouraged to use fear-avoidance management strategies, such as adopting more active interventions for individuals with elevated fear-avoidance beliefs. These general guidelines were used as adjuncts to the professional judgment and clinical reasoning of each physical therapist, which included experience in conceptual methods of neuroplasticity and the treatment of patients with chronic pain.Citation24

Treatment consisted of therapeutic exercise (eg, range of motion [ROM], strengthening, motor control retraining), manual therapy (eg, spinal or peripheral joint mobilization, spinal or peripheral manipulative therapy), patient education (eg, postural education, pain modulation strategies, graded exposure techniques, return to work strategies), and/ or modalities. This clinic implemented a “patient-centered” program that was specific to patient needs and accounted for potential fear-avoidance, so no standardized or protocol-driven treatments were provided.

Data analysis

Analyses were completed using SPSS Statistics software (v 18.0; IBM corp, Armonk, NY). Alpha level was conservatively set at 0.01 due to the number of planned analyses.

Aim 1: gender and anatomical location of musculoskeletal pain

Differences in work-related fear-avoidance were analyzed using 2 × 4 analysis of variance and Bonferroni post hoc testing when appropriate. Effect sizes were computed from estimated marginal means using Cohen’s d.

Aim 2: pain intensity and function

In line with our second aim, correlations and regression models were separated for comparison based on anatomical location of musculoskeletal pain as we have done in our previous studies investigating anatomical location.Citation18,Citation19 Influence of work-related fear-avoidance on intake pain intensity and function level was first analyzed. A Pearson’s Product Moment Correlation was performed to examine simple work-related fear-avoidance by clinical outcome associations, followed by hierarchical regression modeling to account for demographic and clinical variables. For each regression model, age, gender, and pain duration were loaded in the first block, followed by FABQ-W in the second block.

Next, work-related fear-avoidance was examined for association with pain intensity and function level change scores (discharge and intake) from physical therapy treatment. This was investigated in a parallel fashion as with intake scores, with simple associations first determined by Pearson’s Product Moment Correlation. For each hierarchical regression model, age, gender, and pain duration were loaded in the first block, followed by FABQ-W in the second block.

Results

During the data collection period, 672 patients with musculoskeletal pain were treated at an outpatient orthopedic facility. Of these, 359 were excluded due to incomplete intake and discharge assessment measurements, and/or not completing physical therapy prior to date of data collection. Therefore, 313 eligible patients were included in the current analysis. A summary of intake characteristics by anatomical location are provided in .

Table 1 Intake characteristics by anatomical location

Aim 1: gender and anatomical location of musculoskeletal pain

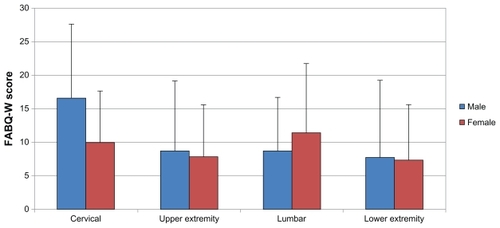

Comparison of FABQ-W scores by gender for the four anatomical locations with musculoskeletal pain are illustrated in . No significant interaction was found to exist between gender and anatomical location of musculoskeletal pain on FABQ-W scores (P > 0.01). A significant main effect was observed for anatomical location of musculoskeletal pain (F (3, 305) = 4.918, P < 0.01). Bonferroni post hoc testing revealed a significant difference in mean FABQ-W scores for patients in the cervical (13.36, standard error [SE] = 1.30) versus lower extremity (7.51, SE = 0.90) group only. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were observed to be small to moderate, ranging from as low as 0.09 (upper extremity versus lower extremity group) to as high as 0.60 (cervical versus lower extremity group) (). Gender was not found to be a significant main effect of work-related fear-avoidance across the four anatomical locations (P > 0.01) ().

Figure 1 Mean raw FABQ-W scores (scale 0–42) with standard deviation; separated by anatomical location of musculoskeletal pain and split by gender.

Table 2 Differences in mean raw FABQ-W scores and effect sizes for four anatomical locations

Aim 2: pain intensity and function

Intake scores

Average intake pain intensity and function scores are provided in . A positive univariate relationship was found between FABQ-W scores and intake pain intensity scores for the cervical (r = 0.437, P < 0.01) and lumbar (r = 0.352, P < 0.01) groups only (), suggesting higher pain intensity was associated with higher fear scores. Hierarchical regression analysis to further examine the association between work-related fear-avoidance and intake pain intensity is reported in . After accounting for demographic and clinical variables (age, gender, pain duration), FABQ-W scores yielded additional unique variance of 19.2%, 6.4%, 10.0%, and 2.0% for cervical, upper extremity, lumbar and lower extremity regions, respectively. Overall variance explained by the final models for intake pain intensity was 20%, 11%, 21%, and 4% for the cervical, upper extremity, lumbar and lower extremity regions, respectively. In line with the correlation findings, a positive association between intake pain intensity and FABQ-W scores was found for the cervical (St Beta = 0.13, P < 0.001) and lumbar (St Beta = 0.08, P < 0.01) regions in the hierarchical regression models.

Table 3 Average pain and function scores by anatomical location

Table 4 Univariate associations between anatomical location and pain/function measures

Table 5 Work-related fear-avoidance contribution to intake pain intensity and functional scores by anatomical location

A negative relationship between FABQ-W scores and intake function level were found for all musculoskeletal pain groups (), suggesting lower function levels for patients with higher work-related fear-avoidance. For influence of work-related fear-avoidance on intake function level, additional unique variance from the FABQ-W was 4.7%, 8.0%, 2.8%, and 10.3% for the cervical, upper extremity, lumbar, and lower extremity regions, respectively. Overall variance explained by the final models for intake function was 52%, 32%, 31%, and 27% for cervical, upper extremity, lumbar and lower extremity regions, respectively. After controlling for demographic and clinical variables, negative associations were observed for FABQ-W scores in the upper (St Beta = −0.54, P < 0.01) and lower extremity (St Beta = −0.62, P < 0.01) regions, only. The contribution of FABQ-W scores to intake function scores did not reach significance (P > 0.01) for the cervical and lumbar spine regions ().

Change scores

Average change in pain intensity and function scores are provided in . A positive correlation was observed for pain intensity change in the lumbar group (r = 0.331, P < 0.01), suggesting larger changes in pain for patients with low back pain and higher work-related fear-avoidance (). However, no other anatomical location had a significant association between work beliefs and change in pain (P > 0.01). Hierarchical regression analysis further examined influence of work-related fear-avoidance on pain intensity change scores (). Additional unique variance for FABQ-W scores was 8.4%, 6.3%, 8.5% and 0.4% for the cervical, upper extremity, lumbar, and lower extremity regions, respectively. Overall variance explained by the final models for change in pain was 10.0%, 10.7%, 14.1% and 2.8% for cervical, upper extremity, lumbar and lower extremity regions, respectively. After controlling for demographic and clinical variables, a positive association was observed for FABQ-W scores in the lumbar region (St Beta = 0.31, P < 0.01) only.

Table 6 Work-related fear-avoidance contribution to changes in pain intensity and functional scores by anatomical location

For function, the only anatomical location associated with change scores was the lower extremity (r = 0.335, P < 0.01) (). This also suggests larger changes in function with higher FABQ-W scores. Hierarchical regression analysis revealed additional unique variance of 0.7%, 7.8%, 0.7%, and 9.0%, cervical, upper extremity, lumbar, and lower extremity regions, respectively. Overall variance explained by the final models for change in function was 19.4%, 44.2%, 24.2%, and 22.4% for cervical, upper extremity, lumbar and lower extremity regions, respectively. After controlling for demographic and clinical variables, a positive association with change in function was observed for FABQ-W scores in the upper (St Beta = 0.30, P = 0.01) and lower extremity (St Beta = 0.31, P < 0.01) regions, only.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of gender and anatomical location of musculoskeletal pain on work-related fear-avoidance for multiple body sites. Results indicate that work-related fear-avoidance with cervical or extremity musculoskeletal pain are of similar magnitude to that reported by patients with low back pain. This finding is consistent with an earlier study examining differences in FABQ-W scores for musculoskeletal pain in cervical versus lumbar regions,Citation12 and suggests that the FABQ-W is an appropriate measure of work-related fear -avoidance for other musculoskeletal regions.

Gender differences in work-related fear-avoidance scores for the four anatomical locations were also examined. Previous investigation into the fear construct (using measures other than the FABQ) found higher levels observed for males with neckCitation12 or low back pain,Citation11,Citation12 as well as unspecified chronic musculoskeletal pain.Citation25 Additionally, a recent multicenter international study of Dutch and Canadian/Swedish population samples found a significant association between gender and fear of movement and/or re-injury, with males demonstrating higher scores.Citation26 In contrast, other psychological constructs like catastrophizing have found consistently higher reports for females.Citation27–Citation29 Nevertheless, the findings in the present study did not support any difference in work-related fear-avoidance reports by gender. It is important to consider that gender may not influence the effect of anatomical location on work-related fear-avoidance.

Comparing influence of work beliefs on pain and function across anatomical locations was not directly addressed with comparisons of mean FABQ-W scores. For these purposes, associations between work-related fear-avoidance and pain intensity or function were examined across the four anatomical locations and, contrary to the authors’ hypothesis, associations were not universally higher for low back pain. Work-related fear-avoidance did provide the largest variance explained for change in pain intensity for the lumbar group, which was also the only group significant for this outcome. Overall, variance explained by work-related fear-avoidance after accounting for demographics were consistently higher for models of function compared with pain intensity, which illustrates the potential importance of work beliefs on function. That said, there was an observed specificity to clinical outcomes by anatomical location after accounting for age, gender, and pain duration. Associations between work-related fear-avoidance and intake pain intensity were found only in patients with spine conditions. In contrast, associations between work-related fear-avoidance and intake function were only found for patients with extremity conditions. Interestingly, these results do not parallel associations with fear of physical activity observed in the prospective cohort study of the same patient population.Citation18 For that analysis, fear of physical activity was found to have a uniform association with pain and function across anatomical location. Comparatively, variance explained by fear of physical activity models was larger than work-related fear-avoidance models for intake scores in all but two instances (cervical model for intake pain, lower extremity model for intake function). Collectively, this may indicate that fear-avoidance is not a uniform construct and that a separate assessment is needed for fear or work and physical activity.

The reason for specificity to clinical outcomes based on anatomical location for work-related fear-avoidance can only be speculated. It is possible that in the presence of neck or low back pain, work beliefs or experiences have a stronger influence over pain intensity because of a unique influence on pain perception for spinal conditions. In other words, specific work beliefs for groups with spine pain may garner a perception that are influential to pain but not to the accompanying functional task. However, the association observed between work-related fear-avoidance and function may be indicative of a unique perceived threat to function outside of work (eg, a participant with a knee injury may relate a task to difficulty walking but not to increased pain). Another possibility may be that the type of work-related tasks performed in the cervical and lumbar groups were linked to a higher pain experience than tasks performed by the extremity groups. However, this does not explain specificity to function for the extremity groups; examination of such effects would require a more complex experimental design.

Regardless of the rationale, the lack of association between work-related fear-avoidance and function for patients with low back pain was a puzzling finding in this study. Waddell et alCitation11 observed a strong association between work-related fear-avoidance and disability (loss of function) in the low back pain cohort used for the original FABQ study, and the authors of the present study have found similar results in their other studies.Citation2–Citation4 One explanation is that functional differences across anatomical locations are related to the metric used. In this study, the CCFOI was implemented instead of the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODQ) that has been used in previous studies of patients with low back pain. The CCFOI has not been utilized as a functional measurement tool, despite its comprehensiveness and standardization across many treatment facilities nationally. However, the ODQ is frequently utilized in this area as a functional measurement tool for low back pain, but it is not appropriate for use in other anatomical locations. Future analysis of the CCFOI, including psychometrics and comparison to the ODQ, may shed light on whether the anatomical specificity of function is related to the measurement tool utilized. A final consideration for lack of association between work-related fear-avoidance and function in the presence of low back pain is the heterogeneity of participants. The sample in the present study included – but was not exclusive to – patients with work-related musculoskeletal injuries. It is possible that with a more specific subgroup of patients, a significant association with function may be found.

Another key finding was the direction of effect observed between work-related fear-avoidance and clinical outcome change scores. Though not a formal hypothesis, it was anticipated that findings would be similar to previous work in this area, where higher work-related fear-avoidance was linked to lower changes in pain intensity and function.Citation2,Citation4 This tendency acts in accordance with fear-avoidance theory, as pain-related fear may produce avoidance behaviors resulting in disability. However, for patients with low back pain, higher work-related fear-avoidance beliefs resulted in larger changes in pain intensity from intake to discharge. Similarly, for patients with upper and lower extremity pain, higher work-related fear-avoidance beliefs resulted in larger changes in function from intake to discharge. Although speculative, this discrepancy may be associated with higher capacity for change or regressions to the mean. Individuals with higher work-related fear-avoidance might have greater potential to demonstrate change compared with individuals with lower work-related fear-avoidance, simply because the distance between units of measurement for intake and discharge are larger.

Limitations of the current study should be considered when interpreting these results. First, work-related factors (eg, mechanism of injury, payor status, employment/return to work status) were not included in this analysis. Previous studies have reported a relationship between fear-avoidance scores and work-related factors.Citation11,Citation12,Citation30–Citation32 Another limitation was that physical therapy treatment, including education and intervention strategies for elevated fear-avoidance, were not standardized. This was intentional so as to replicate a typical outpatient orthopedic environment. However, since specific strategies were not tracked, changes or differences in approach based on level of fear-avoidance status cannot be assessed. Lastly, psychometrics of the modified FABQ-W and the CCFOI have not been directly examined. Though no problems with these measurement tools were observed, the current lack of validation remains a concern.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that work-related fear-avoidance beliefs for patients with neck or extremity pain are similar to patients with low back pain. Gender was not a significant factor in amount of work-related fear-avoidance beliefs by anatomical location. For associations with clinical outcomes, work-related fear-avoidance influenced intake pain intensity in patients with spine pain but not extremity pain. Conversely, only patients with extremity pain demonstrated an influence on intake function. Contrary to fear-avoidance theory and previous work in this area, higher work-related fear-avoidance in this cohort was associated with more, not less, change in pain and function for certain anatomical locations.

Acknowledgement

Publication of this article was funded in part by the University of Florida Open-Access Publishing Fund.

Disclosure

This study was exempt from University of Florida Institutional Review Board since all data were collected as part of routine clinical practice and de-identified before analysis. The authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to this paper.

References

- CrookJMilnerRSchultzIZStringerBDeterminants of occupational disability following a low back injury: a critical review of the literatureJ Occup Rehabil200212427729512389479

- FritzJMGeorgeSZDelittoAThe role of fear-avoidance beliefs in acute low back pain: relationships with current and future disability and work statusPain200194171511576740

- GeorgeSZFritzJMBialoskyJEDonaldDAThe effect of a fear-avoidance-based physical therapy intervention for patients with acute low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trialSpine (Phila Pa 1976)200328232551256014652471

- GeorgeSZFritzJMChildsJDInvestigation of elevated fear-avoidance beliefs for patients with low back pain: a secondary analysis involving patients enrolled in physical therapy clinical trialsJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther2008382505818349490

- VowlesKEGrossRTWork-related beliefs about injury and physical capability for work in individuals with chronic painPain2003101329129812583872

- FritzJMGeorgeSZIdentifying psychosocial variables in patients with acute work-related low back pain: the importance of fear-avoidance beliefsPhys Ther2002821097398312350212

- HoldenJDavidsonMTamJCan the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire predict work status in people with work-related musculoskeletal disorders?J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil201023420120821079299

- FordyceWELearning processes in painSternbachRAThe Psychology of PainNew YorkRaven Press19784972

- LethemJSladePDTroupJDBentleyGOutline of a Fear-Avoidance Model of exaggerated pain perception – IBehav Res Ther19832144014086626110

- VlaeyenJWKole-SnijdersAMBoerenRGvan EekHFear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performancePain19956233633728657437

- WaddellGNewtonMHendersonISomervilleDMainCJA Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disabilityPain19935221571688455963

- GeorgeSZFritzJMErhardREA comparison of fear-avoidance beliefs in patients with lumbar spine pain and cervical spine painSpine200126192139214511698893

- HartDLWernekeMWGeorgeSZScreening for elevated levels of fear-avoidance beliefs regarding work or physical activities in people receiving outpatient therapyPhys Ther200989877078519541772

- ClelandJAFritzJMChildsJDPsychometric properties of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire and Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia in patients with neck painAm J Phys Med Rehabil200887210911717993982

- PivaSRFitzgeraldGKWisniewskiSDelittoAPredictors of pain and function outcome after rehabilitation in patients with patellofemoral pain syndromeJ Rehabil Med200941860461219565153

- GeorgeSZFritzJMChildsJDBrennanGPSex differences in predictors of outcome in selected physical therapy interventions for acute low back painJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther200636635436316776485

- RobinsonMEDanneckerEAGeorgeSZOtisJAtchisonJWFillingimRBSex differences in the associations among psychological factors and pain report: a novel psychophysical study of patients with chronic low back painJ Pain20056746347015993825

- GeorgeSZStrykerSEFear-avoidance beliefs and clinical outcomes for patients seeking outpatient physical therapy for musculoskeletal pain conditionsJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther201141424925921335927

- GeorgeSZCoronadoRABeneciukJMValenciaCWernekeMWHartDLDepressive symptoms, anatomical region, and clinical outcomes for patients seeking outpatient physical therapy for musculoskeletal painPhys Ther201191335837221233305

- ScopazKAPivaSRWisniewskiSFitzgeraldGKRelationships of fear, anxiety, and depression with physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritisArch Phys Med Rehabil200990111866187319887210

- CrossleyKMBennellKLCowanSMGreenSAnalysis of outcome measures for persons with patellofemoral pain: which are reliable and valid?Arch Phys Med Rehabil200485581582215129407

- CareConnections.com [homepage on the Internet]SeattleTherapeutic Associates, Inc2007 [cited 2011 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.careconnections.com/outcomes/index.aspxAccessed April 20, 2011

- SchunkCRuttRTAOS functional index; orthopaedic rehabilitation outcomes toolJ Rehabil Outcomes Meas199825561

- ButlerDSMoseleyGLExplain PainAdelaideNoigroup Publications2003

- BränströmHFahlströmMKinesiophobia in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: differences between men and womenJ Rehabil Med200840537538018461263

- RoelofsJvan BreukelenGSluiterJNorming of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia across pain diagnoses and various countriesPain201115251090109521444153

- KeefeFJLefebvreJCEgertJRAffleckGSullivanMJCaldwellDSThe relationship of gender to pain, pain behavior, and disability in osteoarthritis patients: the role of catastrophizingPain200087332533410963912

- EdwardsRRHaythornthwaiteJASullivanMJFillingimRBCatastrophizing as a mediator of sex differences in pain: differential effects for daily pain versus laboratory-induced painPain2004111333534115363877

- ForsytheLPThornBDayMShelbyGRace and sex differences in primary appraisals, catastrophizing, and experimental pain outcomesJ Pain2011125563572 Epub 2011 Jan 2921277836

- ClelandJAFritzJMBrennanGPPredictive validity of initial fear avoidance beliefs in patients with low back pain receiving physical therapy: is the FABQ a useful screening tool for identifying patients at risk for a poor recovery?Eur Spine J2008171707917926072

- GrotleMVøllestadNKVeierødMBBroxJIFear-avoidance beliefs and distress in relation to disability in acute and chronic low back painPain2004112334335215561390

- PfingstenMKröner-HerwigBLeibingEKronshageUHildebrandtJValidation of the German version of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ)Eur J Pain20004325926610985869