Abstract

Complementary and alternative medicine includes a number of exercise modalities, such as tai chi, qigong, yoga, and a variety of lesser-known movement therapies. A meta-analysis of the current literature was conducted estimating the effect size of the different modalities, study quality and bias, and adverse events. The level of research has been moderately weak to date, but most studies report a medium-to-high effect size in pain reduction. Given the lack of adverse events, there is little risk in recommending these modalities as a critical component in a multimodal treatment plan, which is often required for fibromyalgia management.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a debilitating chronic pain condition affecting ~15 million persons in the USA and is one of the more severe disorders on the continuum of persistent pain.Citation1–Citation4 FM results in profound suffering, including widespread musculoskeletal pain and stiffness, fatigue, disturbed sleep, dyscognition, affective distress, and very poor quality of life.Citation5,Citation6 Among FM patients, 20%–50% work few or no days despite being in their peak wage-earning years.Citation6,Citation7 Disability payments are received by 26%–55% of FM patients compared with the national average of 2% of patients who receive disability payments from other causes.Citation7–Citation9 Furthermore, health care costs are three times higher among FM patients compared with matched controls.Citation9

Diminished aerobic fitness in FM has been documented for almost three decades, and recent studies report that the average 40-year-old with FM has fitness findings expected for a healthy 70 to 80-year-old, and FM has now also been associated with increased mortality.Citation2,Citation3,Citation11–Citation14 Tailoring exercise to patients with FM requires an understanding of the relevant pathophysiology. FM is likely due in part to altered pain processing in the central and peripheral nervous system.Citation15–Citation17 Additional pathophysiologic factors include genetic predispositions, autonomic dysfunction, and emotional, physical, or environmental stressors.Citation18 Neurohormonal and inflammatory dysfunctions are implicated in muscle microtrauma and ischemia, a potent pain generator during and after exercise.Citation15,Citation18–Citation24 The majority of persons with FM have four or more comorbid pain or central sensitivity disorders, including irritable bowel/bladder, headaches, pelvic pain, regional musculoskeletal pain syndromes (such as low back pain), chronic fatigue, and restless leg syndromes, suggesting shared pain processing in these common comorbidities.Citation25–Citation27 Multiple symptoms and poor physical function are underpinned by physiologic abnormalities found in FM and other chronic pain conditions.

Drug therapies for FM offer some help, improving pain by ~30% and function by ~20%. Drug access and costs are challenging, however, as none are available in generic formulation. Further, they carry safety concerns and may produce side effects, such as nausea, edema, weight gain, or tachycardia.Citation27–Citation31 Unfortunately, no new FM drugs are in Phase III testing or under Food and Drug Administration (FDA) review, shifting the urgency to the development of novel, safe, effective nonpharmacological strategies, including exercise.Citation32

Based on results of over 100 studies, exercise has been strongly recommended as an adjunct to drug therapy for FM.Citation33–Citation36 Of these studies, approximately 80% are aerobic or mixed-type (aerobic, strength, flexibility).Citation37–Citation44 New data have emerged since these key position statements were published. Namely, a meta-analysis of studies with low attrition concluded that immediately postintervention, high quality aerobic or mixed modality exercise reliably restored physical function or fitness (d = 0.65) and health-related quality of life (d = −0.40), while exerting no significant effects on sleep (d = 0.01). Effect sizes for pain were small (d = −0.31) and not sustained at follow up (d = 0.13).Citation41 Similarly, 14 strength or stretching studies consistently demonstrated improvements in fatigue and physical function but inconsistently improved other FM symptoms.Citation39,Citation42 Studies included in the meta-analysis had a median attrition of 67% (range 27%–90%), suggesting that the interventions themselves were not acceptable. Some early programs dosed the intervention too high (exercise frequency, intensity, and timing) or required medication washout, leading to an attrition rate averaging approximately 40%. Others selected inappropriate exercise modalities, such as running, fast dancing, or high-intensity aerobics, resulting in 62%–67% attrition.Citation45,Citation46

In search of more comprehensive and continued symptom relief, FM patients have been increasingly adopting complementary and alternative exercise therapies, such as qigong, tai chi, yoga, and a variety of lesser-known movement therapies.Citation47,Citation48 Qigong and tai chi both have origins in the Chinese martial arts. They involve physical movement integrated with mental focus and deep breathing. They seek to cultivate and balance qi (chi), which is sometimes translated as “intrinsic life energy.” Yoga is “a union of mind and body” with origins in ancient Indian philosophy. In yoga, physical postures (“asanas”) are generally practiced in tandem with breathing techniques (“pranayama”) and meditation or relaxation.

Langhorst et alCitation49 recently published a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on meditative movement in FM, concluding that these modalities were safe and effective for selected FM symptoms. The aim of this paper is to extend Langhorst’s work by providing a comprehensive review of a broader array of land-based complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) FM exercise studies, including early-stage research. For the purposes of this review, exercise is defined as planned, structured physical activity whose goal is to improve one or more of the major components of fitness – aerobic capacity, strength, flexibility, or balance. CAM is defined as “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered to be part of conventional medicine.”Citation50

Material and methods

Literature search strategy

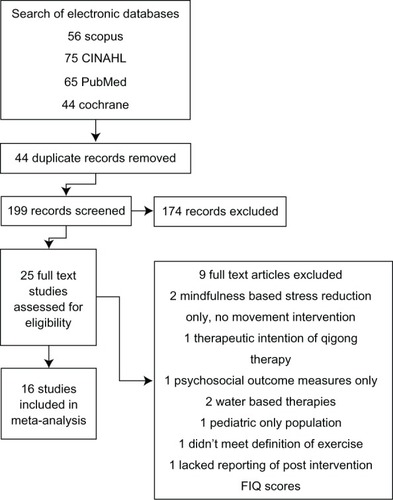

Electronic databases were screened during October 2012, including SciVerse Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed/ Medline, Cochrane Library, and PsychInfo. The key medical subject heading (MeSH) terms for initial inclusion were “fibromyalgia” and “fibromyalgia syndrome” combined with “yoga,” “tai chi,” “pilates,” “taiji,” and “qigong.” To maximize the search results, no search limitations of language, year, or study design were implemented. Additional studies were identified through the bibliographies of selected studies and personal contact with researchers in the field.

Selection criteria

To determine their initial eligibility, all potential studies were retrieved in full text and reviewed for the inclusion criteria. All three authors independently screened all identified full-text articles, to determine whether the study met the inclusion criteria. To be included in this review, studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) enrollment of participants 21 years of age and older who met the standardized criteria for FM diagnosis, (2) study intervention met the definitions for CAM and land-based exercise, and (3) inclusion and reporting of pre- and post-Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) total score or numeric pain rating scale scores.Citation51,Citation52 This means that CAM studies with very low levels of exertion, such as studies of body awareness therapies, breathing studies, and mindfulness-based stress reduction (which generally offers very brief yoga in two out of eight sessions), were not included. Additionally, we excluded water-based CAM therapies, such as tai chi in water and yoga/breathing in water, as it is unclear whether the benefit derived from balneotherapeutic effects or physical movement and mindful techniques ().Citation53,Citation54

Data extraction

All review authors participated in data extraction. Data were extracted in the following content areas: study design, type of CAM exercise, sample size, subject characteristics (age and gender), treatment duration, frequency and dose, adherence to treatment, attrition rates, and outcome variables and results. Any discrepancies between authors were discussed and consensus obtained. When studies did not include enough information to calculate the effect size estimates on pain, the authors were contacted to request the data required for a complete statistical analysis. Most of these reported point estimates rather than effect sizes. All studies for which effect sizes could not be calculated, were excluded from this review.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was completed using Comprehensive Meta Analysis software, Version 2.2.064 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA). Standard formulas were used to calculate standardized mean differences and standard errors.Citation55 Overall estimates of treatment effect used a random effects meta-analysis.Citation56 Subgroup analyses were conducted with respect to treatment modality. A common among-study variance component across subgroups was not used when calculating the effect size of the individual modalities.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the selected studies was assessed using the Jadad score,Citation57 assessing for randomization, blinding, and clear explanations for study dropouts. While Jadad scoring is intended for RCTs, the authors thought that it was a good, if simple, measure of methodological quality, allowing nonrandomized trials in this review the possibility of a score of 0 or 1 and RCTs a maximum score of 3. Normally the Jadad score has a range of 0 to 5, but as it is not possible to blind the interventionist to the treatment in CAM exercise, the maximum achievable score is 3. The average score for the studies in this review was 1.7 (range 1 to 3).

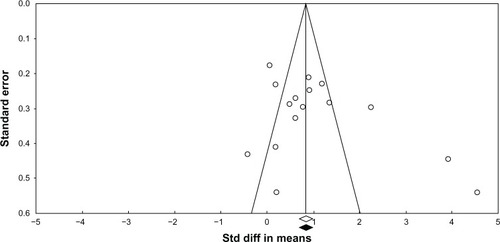

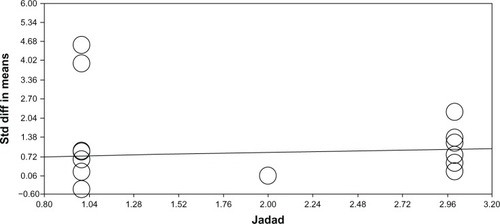

Sensitivity and validity analysis

A funnel plot was constructed of standard differences (Std diff) in means by standard errors, with two standard deviations displayed. A random distribution of studies indicated a low publication bias. A regression of the Jadad score on the Std diff in means was calculated. The slope is indicative of publication bias by quality of study. A slope of zero indicates that there was no bias.

Results

Study design

As the field has a relatively low number of reported RCTs, we included time-series trials. Due to this limitation, the relative study strength was moderately low. Time-series trials were adjusted for the relative overestimation of strength. However, one can see that the time series still represented some of the largest reported effects. reports the details of each study.

Table 1 Summary of included trials

Participants

A total of 832 FM patients participated in the reviewed studies, with 490 allocated to the CAM exercise interventions. The median of the sample size for the CAM exercise interventions was 23 (range 6–64). The median percentage of patients completing the study was 81%, and there was no significant difference in dropout among those studies that included a comparison arm.Citation58–Citation75 In all of the studies, the FM diagnosis was made in accordance with the American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria.Citation52

Outcomes

In all studies, except for one by Curtis et al, the FIQ total score or FIQ Pain Score was used as the primary outcome. The Curtis et al study used the McGill Pain Questionnaire, and in this case, the total McGill Pain Questionnaire was analyzed.Citation64 Most studies reported both pre- and posttreatment scores, with a number reporting longer-term follow ups. For the purpose of the current analysis, only pre- and post-effects were assessed. There were no significant differences among the baseline means and standard deviations across the studies.

Meta-analyses

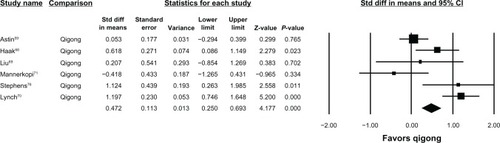

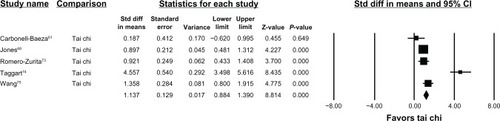

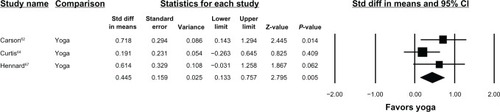

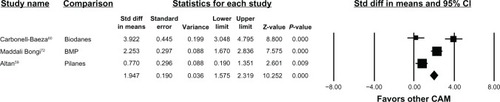

The standard difference in means (0.84), and standard errors (0.07) for CAM exercise, indicates a statistically significant (P = 0.00) and positive outcome. The individual forest plots for qigong, tai chi, yoga, and all others are reported in – respectively. With the exception of two studies, all studies reported positive outcomes.Citation71 Of those not reporting positive outcomes, Mannerkorpi and ArndorwCitation71 found no difference between 14 weeks of qigong versus a sedentary “usual care” control in 36 FM patients. Likewise, Carbonell-Baeza et alCitation61 concluded that a 4-month male tai chi study (n = 6) was negative for symptom improvement.

Sensitivity analyses

A funnel plot of the Std diff in means indicates that if the standard difference in means (0.84) is true, there is little evidence for reporting bias. The majority of studies fell within two standard deviations, with an equal number of studies falling outside this on either side of the plot (). A regression of the Jadad scores on the standard difference of means indicates more variation reported in the lower scores and less in the higher scores, with a slight increase in the slope seen with higher scores ().

Figure 6 Funnel plot of standard error by standard difference in means.

Figure 7 Regression of Jadad score on standard difference in means (Jadad et al, 1996).Citation57

Validity analysis

There was a significant amount of heterogeneity in the studies presented in this analysis. This can be seen in the means and confidence intervals in the subplots. The distributions of the forest plots suggest that the results are randomly distributed, indicating that the results are mostly consistent within each type of exercise.

Discussion

The data presented support the likely safety of CAM exercise interventions, as 832 participants were enrolled in 16 studies and 81% completed the studies without differential attrition by study arm or exercise modality.Citation58–Citation75 Only one study reported negative side effects (increased shoulder pain and plantar fasciitis) in two study participants.Citation70 All studies reported that there were no serious adverse events.

The data also support some degree of efficacy of several of the CAM exercise interventions in improving overall FM symptoms and physical function. Taken as a whole, the data do not indicate that any one intervention type is consistently superior to another, though the strongest effects were for the exercise modalities with the largest number of trials: qigong (Std diff in means 0.47; P < 0.000) and tai chi (Std diff in means 1.14; P < 0.000). Further support for qigong comes from a trial excluded from this analysis. Stephens et alCitation76 randomized 30 children (ages 8–18) with FM to aerobics or qigong. There was no difference between study arms, although qigong was intended to be the control group. The qigong group did demonstrate significant within-group changes, indicating that pediatric CAM exercise interventions may be a promising area of research. This is critical, as few interventions address pediatric FM even though its recognition as a valid diagnosis is increasing. This may indicate that mind–body exercises may be a feasible therapeutic option across a wider range of developmental states.Citation76–Citation80

Complete data were only available for three yoga trials (two were open labeled) but were positive (Std diff in means 0.45; P < 0.015).Citation62,Citation64,Citation67 Additional support for the benefit of yoga is found in two studies that are not represented in the analyses due to missing data. da Silva et alCitation65 randomized 40 women with FM into an individually delivered intervention of “relaxing” yoga with or without additional tui na (massage). Both groups experienced clinically and statistically significant reductions in FIQ total scores, but there was no difference between treatment arms. Another trial (n = 10) noted a 28% improvement in FIQ total scores following eight weeks of gentle Hatha yoga.Citation81 Three other CAM-based exercise studies were positive, but the interventions have yet to be replicated (pilates, Biodanza, and Resseguier with body movement and perception).Citation58,Citation60,Citation72 Pilates is a series of nonimpact strength, flexibility, and breathing exercises designed by Joseph Pilates to promote inner awareness and core stability. Biodanza, literally “life-dance,” is a program of exercise that seeks to optimize self-development and deepen self-awareness. It most often uses dance, music, singing, and other movements to promote positive feelings, emotional expression, and connection to others and to nature. Resseguier is based on selected soft, low-impact gymnastic movements integrated with postural self-control, body alignment, and relaxation.

The data are consistent with an earlier rigorous report on “mindful” meditative movement therapies that concluded that these therapies were safe and effective for reducing sleep disturbances, fatigue, and depression, and improving quality of life. In subanalyses, the authors found that only yoga also relieved pain.Citation50 However, that meta-analysis was comprised of only RCTs (n = 7). The current data extend these findings by demonstrating efficacy in a combination of FM symptoms and physical function, in a larger number of studies (n = 16).

This meta-analysis shows that research in the area was at an early state (six open-labeled studies), although regressing by Jadad score showed that there was a nonsignificant difference by effect size. This may indicate that early-stage studies are not likely to overreport effect.

This study does have limitations, the greatest being that six of the studies were open labeled. Others may argue, however, that open-labeled trials are appropriate in early-phase research when safety, feasibility, and effect sizes are being determined.Citation82 Further, because open-labeled studies were included, community-based exercise studios and instructors were tested, leading the field toward effectiveness rather than efficacy outcomes. The studies were generally small (average n = 51.5; range 6 to 128 participants), limiting their power and the ability to test multiple comparisons or to profile responders’ reliability.

Another limitation is that the studies were largely conducted in middle-aged women, in America and Europe. This is important, as many CAM exercise studies have been conducted in India and China, where many of these traditions are rooted (however, those studies were not available in English or from major database sources). Moreover, differential effects may be found in men, minorities, children and elders. Another limitation is that all the trials employed a single interventionist and did not rate treatment expectancy. It is possible, therefore, that a charismatic or caring instructor, rather than the intervention itself, may have been responsible for the beneficial outcome, although this is less likely in the trials that have been replicated (qigong, tai chi, and yoga). Future effectiveness studies could use multiple instructors.

A goal of future studies should include the standardization of exercise protocols, including scripting for mindfulness, posture sequences, and a range of modifications based on the patient’s physical ability. To date, studies have varied considerably in exercise dose and have not always provided adequate description of the intervention to allow replication. Publishing protocols in peer-reviewed journals would provide opportunities for a more detailed description of the actual intervention and for pictures of the less common poses or physical strategies. This is important because people with FM are likely to be in poor physical condition, have joint hypermobility, and poor balance, and may be at an increased risk for injury.Citation42

Future studies should incorporate validated scales such as the revised FIQ (FIQ-R), Brief Pain Inventory, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale, and Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire.Citation83,Citation84 Full reporting of data and statistical tests will allow for more seamless comparison in future trials. Some FM exercise studies now report the number needed to treat, based on Patients’ Global Impression of change (PGIC) scale, which allows for direct comparison with pharmaceutical trials.Citation85 Similarly, work is underway to develop a responder index.Citation86

In conclusion, the CAM-based exercise therapies reviewed are likely safe, and no serious adverse events were reported in any study. These exercise programs were somewhat efficacious for FM pain, with many studies reporting improvement in overall FM symptoms and physical function. However, the majority of studies had lower methodological quality. There is a need for large, rigorous trials with active parallel arms–such as traditional aerobic exercise compared with CAM-based exercise – to extend this body of evidence.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- JainAKCarruthersBMvan de SandeMIFibromyalgia syndrome: Canadian clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols – A consensus documentJ Musculoskelet Pain20041143107

- MacfarlaneGJMcBethJSilmanAJWidespread body pain and mortality: prospective population based studyBMJ2001323731466266511566829

- MacfarlaneGJChronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia: Should reports of increased mortality influence management?Current Rheumatol Rep200575339341

- WhiteKPHarthMClassification, epidemiology, and natural history of fibromyalgiaCurr Pain Headache Rep20015432032911403735

- BurckhardtCSBjelleAPerceived control: A comparison of women with fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and systematic lupus erythematosus using a Swedish version of the rheumatology attitudes indexScand J Rheumatol19962553003068921923

- LedinghamJDohertySDohertyMPrimary fibromyalgia syndrome – an outcome studyBr J Rheumatol19933221391428428227

- WolfeFAndersonJHarknessDWork and disability status of persons with fibromyalgiaJ Rheumatol1997246117111789195528

- MartinezJEFerrazMBSatoELAtraEFibromyalgia versus rheumatoid arthritis: a longitudinal comparison of the quality of lifeJ Rheumatol19952222702747738950

- BergerADukesEMartinSEdelsbergJOsterGCharacteristics and healthcare costs of patients with fibromyalgia syndromeInt J Clin Pract20076191498150817655684

- JonesJRutledgeDNJonesKDMatallanaLRooksDSSelf-assessed physical function levels of women with fibromyalgia: a national surveyWomens Health Issues200818540641218723374

- JonesKDKingLAMistSDBennettRMHorakFBPostural control deficits in people with fibromyalgia: a pilot studyArthritis Res Ther2011134R12721810264

- Carbonell-BaezaAAparicioVASjöströmMRuizJRDelgado-FernándezMPain and functional capacity in female fibromyalgia patientsPain Med201112111667167521939495

- PantonLBKingsleyJDTooleTA comparison of physical functional performance and strength in women with fibromyalgia, age- and weight- matched controls, and older women who are healthyPhys Ther200686111479148817079747

- JensenKBKosekEPetzkeFEvidence of dysfunctional pain inhibition in Fibromyalgia refected in rACC during provoked painPain20091441–29510019410366

- StaudRNagelSRobinsonMEPriceDDEnhanced central pain processing of fibromyalgia patients is maintained by muscle afferent input: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyPain20091451–29610419540671

- RobinsonMECraggsJGPriceDDPerlsteinWMStaudRGray matter volumes of pain-related brain areas are decreased in fibromyalgia syndromeJ Pain201112443644321146463

- LandisCASleep, pain, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndromeHandb Clin Neurol20119861363721056214

- JonesKDDeodharPLorentzenABennettRMDeodharAAGrowth hormone perturbations in fibromyalgia: a reviewSemin Arthritis Rheum200736635737917224178

- RossRLJonesKDBennettRMWardRLDrukerBJWoodLJPreliminary evidence of increased pain and elevated cytokines in fibromyalgia patients with defective growth hormone response to exerciseOpen Immunol20103918

- WilliamsDAClauwDJUnderstanding fibromyalgia: lessons from the broader pain research communityJ Pain200910877779119638325

- StaudRPeripheral pain mechanisms in chronic widespread painBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol201125215516422094192

- ElvenASiösteenAKNilssonAKosekEDecreased muscles blood flow in fibromyalgia patients during standardised muscle exercise: a contrast media enhanced colour Doppler studyEur J Pain200610213714416310717

- GeHYArendt-NielsenLMadeleinePAccelerated muscle fatigability of latent myofascial trigger points in humansPain Med201213795796422694218

- SrikueaRSymonsTBLongDEFibromyalgia is associated with altered skeletal muscle characteristics which may contribute to post-exertional fatigue in post-menopausal womenArthritis Rheum Epub1112012

- YunusMBFibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromesSemin Arthritis Rheum200736633935617350675

- AaronLABurkeMMBuchwaldDOverlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorderArch Intern Med2000160222122710647761

- CroffordLJRowbothamMCMeasePJPregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialArthritis Rheum20055241264127315818684

- HäuserWPetzkeFSommerCComparative efficacy and harms of duloxetine, milnacipran, and pregabalin in fibromyalgia syndromeJ Pain201011650552120418173

- MeasePJChoyEHPharmacotherapy of fibromyalgiaRheum Dis Clin North Am200935235937219647148

- MeasePJClauwDJGendreauRMThe efficacy and safety of milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia. a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Rheumatol200936239840919132781

- RussellIJMeasePJSmithTREfficacy and safety of duloxetine for treatment of fibromyalgia in patients with or without major depressive disorder: Results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trialPain2008136343244418395345

- StaudRSodium oxybate for the treatment of fibromyalgiaExpert Opin Pharmacother201112111789179821679091

- CarvilleSFArendt-NielsenSBliddalHEULAREULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndromeAnn Rheum Dis200867453654117644548

- GoldenbergDLBurckhardtCCroffordLManagement of fibromyalgia syndromeJAMA2004292192388239515547167

- HäuserWArnoldBEichWManagement of fibromyalgia syndrome – an interdisciplinary evidence-based guidelineGer Med Sci20086 Doc 14

- SimJAdamsNSystematic review of randomized controlled trials of nonpharmacological interventions for fibromyalgiaClin J Pain200218532433612218504

- BrosseauLWellsGATugwellPOttawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for aerobic fitness exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 1Phys Ther200888785787118497301

- BrosseauLWellsGATugwellPOttawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for strengthening exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 2Phys Ther200888787388618497302

- BuschASchachterCLPelosoPMBombardierCExercise for treating fibromyalgia syndromeCochrane Database Syst Rev20023CD00378612137713

- HäuserWKlosePLanghorstJEfficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsArthritis Res Ther2010123R7920459730

- JonesKDLiptanGLExercise interventions in fibromyalgia: clinical applications from the evidenceRheum Dis Clin North Am200935237339119647149

- BuschAJWebberSCBrachaniecMExercise therapy for fibromyalgiaCurr Pain Headache Rep201115535836721725900

- KelleyGAKelleyKSHootmanJMJonesDLExercise and global well-being in community-dwelling adults with fibromyalgia: a systematic review with meta-analysisBMC Public Health20101019820406476

- CazzolaMAtzeniFPilaffFStisiSCassisiGSarzi-PuttiniPWhich kind of exercise is best in fibromyalgia therapeutic programmes? A practical reviewClin Exp Rheumatol2010286 Suppl 63S117S12421176431

- MeyerBBLemleyKJUtilizing exercise to affect the symptomology of fibromyalgia: a pilot studyMed Sci Sports Exerc200032121691169711039639

- NørregaardJLykkegaardJJMehlsenJDanneskiold-SamsøeBExercise training in treatment of fibromyalgiaJ Musculoskelet Pain1997517179

- MistSDJonesKDCarsonJWYoga Internet Survey in Fibromyalgia: A K23 SubprojectNational State of the Science Congress on Nursing Research2012 September 13–15Washington DC, USA

- Wahner-RoedlerDLElkinPLVincentAUse of complementary and alternative medical therapies by patients referred to a fibromyalgia treatment program at a tertiary care centerMayo Clin Proc2005801556015667030

- LanghorstJKlosePDobosGJBernardyKHäuserWEfficacy and safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsRheumatol Int201233119320722350253

- nccam.nih.gov [homepage on the Internet]What is complementary and alternative medicine?National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine2008 [updated July 2011]. Available from: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam#definingcamAccessed October 30, 2012

- WolfeCSmytheHAYunusMBThe American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria CommitteeArthritis Rheum19903321601722306288

- BurckhardtCSClarkSRBennettRMThe fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQ): development and validationJ Rheumatol1991187287331865419

- CalandreEPRodriguez-ClaroMLRico-VillademorosFVilchezJSHidalgoJDelgado-RodriguezAEffects of pool-based exercise in fibromyalgia symptomatology and sleep quality: a prospective randomised comparison between stretching and Ai ChiClin Exp Rheumatol2009275 Suppl 56S21S2820074435

- IdeMRLaurindoLMMRodrigues-JuniorALTanakaCEffect of aquatic-respiratory exercise-based program in patients with fibromyalgiaInt J Rheumat Dis2008112131140

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]The Cochrane Collaboration2011 Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.orgAccessed January 23, 2013

- HigginsJPThompsonSGQuantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysisStat Med200221111539155812111919

- JadadARMooreRACarrollDAssessing the quality of reports of randomized controlled trials: is blinding necessary?Control Clin Trials19961711128721797

- AltanLKorkmazNBingolUGunayBEffect of pilates training on people with fibromyalgia syndrome: a pilot studyArch Phys Med Rehabil200990121983198819969158

- AstinJABermanBMBausellBLeeWLHochbergMForysKLThe efficacy of mindfulness meditation plus Qigong movement therapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trialJ Rheumatol200330102257226214528526

- Carbonell-BaezaAAparicioVAMartins-PereiraCMEfficacy of Biodanza for treating women with fibromyalgiaJ Altern Complement Med201016111191120021058885

- Carbonell-BaezaARomeroAAparicioVAPreliminary findings of a 4-month Tai Chi intervention on tenderness, functional capacity, symptomatology, and quality of life in men with fibromyalgiaAm J Mens Health20115542142921406488

- CarsonJWCarsonKMJonesKDBennettRMWrightCLMistSDA pilot randomized controlled trial of the Yoga of Awareness program in the management of fibromyalgiaPain2010151253053920946990

- ChenKWHassettALHouFStallerJLichtbrounASA pilot study of external qigong therapy for patients with fibromyalgiaJ Altern Complement Med200612985185617109575

- CurtisKOsadchukAKatzJAn eight-week yoga intervention is associated with improvements in pain, psychological functioning and mindfulness, and changes in cortisol levels in women with fibromyalgiaJ Pain Res2011418920121887116

- da SilvaGDLorenzi-FilhoGLageLVEffects of yoga and the addition of Tui Na in patients with fibromyalgiaJ Altern Complement Med200713101107111318166122

- HaakTScottBThe effect of Qigong on fibromyalgia (FMS): a controlled randomized studyDisabil Rehabil200830862563317852292

- HennardJA protocol and pilot study for managing fibromyalgia with yoga and meditationInt J Yoga Therapy201121109121

- JonesKDShermanCAMistSDCarsonJWBennettRMLiFA randomized controlled trial of 8-form Tai Chi improves symptoms and functional mobility in fibromyalgia patientsClin Rheumatol20123181205121422581278

- LiuWZahnerLCornellMBenefit of Qigong exercise in patients with fibromyalgia: a pilot studyInt J Neurosci20121221165766422784212

- LynchMSawynokJHiewCMarconDA randomized controlled trial of qigong for fibromyalgiaArthritis Res Ther2012144R178R18922863206

- MannerkorpiKArndorwMEfficacy and feasibility of a combination of body awareness therapy and qigong in patients with fibromyalgia: a pilot studyJ Rehabil Med200436627928115841606

- Maddali BongiSDi FeliceCDel RossoAEfficacy of the “body movement and perception” method in the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: an open pilot studyClin Exp Rheumatol2011296 Suppl 69S12S1821813057

- Romero-ZuritaACarbonell-BaezaAAparicioVARuizJRTercedorPDelgado-FernándezMEffectiveness of a tai-chi training and detraining on functional capacity, symptomatology and psychological outcomes in women with fibromyalgiaEvid Based Complement Alternat Med2012201261419622649476

- TaggartHMArsianianCLBaeSSinghKEffects of Tai Chi exercise on fibromyalgia symptoms and health-related quality of lifeOrthop Nurs200322535336014595996

- WangCSchmidCHRonesRA randomized trial of tai chi for fibromyalgiaN Engl J Med2010363874375420818876

- StephensSFeldmanBMBradleyNFeasibility and effectiveness of an aerobic exercise program in children with fibromyalgia: Results of a randomized controlled pilot trialArthritis Rheum200859101399140618821656

- AnthonyKKSchanbergLEJuvenile primary fibromyalgia syndromeCurr Rheumatol Rep20013216517111286673

- BuskilaDPediatric fibromyalgiaRheum Dis Clin North Am200935225326119647140

- GedaliaAGarcíaCOMolinaJFBradfordNJEspinozaLRFibromyalgia syndrome: experience in a pediatric rheumatology clinicClin Exp Rheumatol200018341541910895386

- SiegelDMJanewayDBaumJFibromyalgia syndrome in children and adolescents: clinical features at presentation and status at follow-upPediatrics19981013 Pt 13773829481000

- RudrudLGentle Hatha yoga and reduction of fibromyalgia-related symptoms: a preliminary reportInt J Yoga Therap2012225357

- MeinertCLClinical Trials: Design, Conduct, and AnalysisNew YorkOxford University Press1986

- WilliamsDAArnoldLMMeasures of fibromyalgia: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20), Medical Outcomes Study (MOS), Sleep Scale, and Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire (MASQ)Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201163Suppl 11S86S9722588773

- BennettRMFriendRJonesKDWardRHanBKRossRLThe revised FM impact questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric propertiesArthritis Res Ther2009114R12019664287

- WilliamsDAKuperDSegarMMohanNShethMClauwDJInternet-enhanced management of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trialPain2010151369470220855168

- MeasePJClauwDJChristensenROMERACT Fibromyalgia Working GroupToward development of a fibromyalgia responder index and disease activity score: OMERACT module updateJ Rheumatol20113871487149521724721