Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to examine the main reasons for inpatient or outpatient visits after initiating duloxetine or pregabalin.

Methods

Commercially insured patients with fibromyalgia and aged 18–64 years who initiated duloxetine or pregabalin in 2006 with 12-month continuous enrollment before and after initiation were identified. Duloxetine and pregabalin cohorts with similar demographics, pre-index clinical and economic characteristics, and pre-index treatment patterns were constructed via propensity scoring stratification. Reasons for inpatient admissions, physician office visits, outpatient hospital visits, emergency room visits, and primary or specialty care visits over the 12 months post-index period were examined and compared. Logistic regression was used to assess the contribution of duloxetine versus pregabalin initiation to the most common reasons for visits, controlling for cross-cohort differences.

Results

Per the study design, the duloxetine (n = 3711) and pregabalin (n = 4111) cohorts had similar demographics (mean age 51 years, 83% female) and health care costs over the 12-month pre-index period. Total health care costs during the 12-month post-index period were significantly lower for duloxetine patients than for pregabalin patients ($19,378 versus $27,045, P < 0.05). Eight of the 10 most common reasons for inpatient admissions and outpatient hospital (physician office, emergency room, primary or specialty care) visits were the same for both groups. Controlling for cross-cohort differences, duloxetine patients were less likely to be hospitalized due to an intervertebral disc disorder or major depressive disorder, to have a physician office visit due to nonspecific backache/other back/neck pain (NB/OB/NP) disorder, or to go to specialty care due to a soft tissue, NB/OP/NP, or intervertebral disc disorder. However, duloxetine patients were more likely to have a primary care visit due to a soft tissue disorder, essential hypertension, or other general symptoms.

Conclusion

Among similar commercially insured patients with fibromyalgia who initiated duloxetine or pregabalin, duloxetine patients had significantly lower health care costs over the 12-month post-index period. The leading reasons for inpatient or outpatient visits were also somewhat different.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a chronic pain disorderCitation1–Citation8 characterized by widespread muscle pain and a heightened and painful response to gentle touch at multiple tender points.Citation1–Citation10 About 4–10 million people in the US and 3%–6% of the world population have fibromyalgia,Citation1,Citation4–Citation7,Citation11–Citation18 and the highest prevalence occurs among women and people with a family history of fibromyalgia.Citation4–Citation7,Citation9 Patients with fibromyalgia often experience other conditions, such as fatigue, sleep deprivation, and depression,Citation19–Citation22 which may have a negative impact on general functioning and overall quality of life.Citation23–Citation25

Up until now, treatment for fibromyalgia has been mainly aimed at symptom management through pharmacologic therapy, behavioral intervention, physical therapy, exercise, or alternative medicines.Citation26–Citation34 Among the various pharmacologic therapies used by patients with fibromyalgia, duloxetine (2008), pregabalin (2007), and milnacipran (2009) are the only ones approved for the management of fibromyalgia by the US Food and Drug Administration. A recent publication from our previous study among commercially insured patients with fibromyalgia suggested that individuals who initiated duloxetine had better medication compliance and significantly lower direct medical costs than similar patients (demographics, comorbidities, prior total health care costs, and prior medication treatment) who initiated pregabalin.Citation35 Although our previous study found that most of the cost difference was from outpatient services followed by inpatient care,Citation35 we did not examine what medical conditions led to inpatient admissions or outpatient visits among similar patients with fibromyalgia who initiated duloxetine or pregabalin, and we also did not explore how different health care services were provided for these patients.

Using the same study design on the same patients as examined in our previous study,Citation35 we used a comprehensive disease classification to examine and compare the most common reasons leading to inpatient admissions, hospital outpatient visits, physician office visits, emergency room visits, primary care visits, and specialty care visits among similar commercially insured patients with fibromyalgia who initiated duloxetine versus pregabalin in 2006. Logistic regression was used to assess the contribution of initiation of duloxetine versus pregabalin to the most common reasons, controlling for cross-cohort differences.

Materials and methods

Data source

Deidentified insurance claims from the Thomson Reuters MarketScan® Commercial Claims databases 2005–2007 were examined. The MarketScan databases are compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and contain enrollment details, inpatient and outpatient data, and pharmacy claims for individuals covered by over 100 self-insured employers and health plans geographically located throughout the United States. All files can be linked via a unique personal identifier. Demographics, health plan enrollment, health care utilization and costs in inpatient and outpatient settings, and outpatient pharmacy claims are provided for each individual.

Design and duration

This study used a retrospective cohort design. Patients with fibromyalgia who initiated duloxetine or pregabalin in 2006 were grouped into duloxetine or pregabalin cohorts based on the medication initiated. Initiation was defined as a 90-day absence of the initiated medication, with the first initiation date as the index date. The study duration included a 12-month period preceding initiation (pre-index period) and a 12-month period following initiation (post-index period).

Sample selection

As described in our previous publication,Citation35,Citation36 individuals who initiated (a 90-day medication gap) duloxetine or pregabalin in 2006 were first identified. All selected patients were required to: have at least one fibromyalgia diagnosis (ICD-9-CM 729.1) during the 12-month pre-index period, be aged between 18 and 64 years as of the index date, have 12-month continuous enrollment in the pre-index and post-index periods, and have 31+ total duloxetine or pregabalin supply days over the entire 12-month post-index period. Duloxetine initiators with a diagnosis of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (ICD-9CM 250.6x, 357.2x) or depression (ICD-9-CM 296.2x, 296.3x, 300.4x, 309.1x, or 311.xx) during the 12-month pre-index period were excluded. Pregabalin patients with a diagnosis of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, post-herpetic neuralgia (ICD-9-CM 053.11, 053.12, 053.19), or epilepsy (ICD-9-CM 345.xx) over the 12-month pre-index period were also excluded.

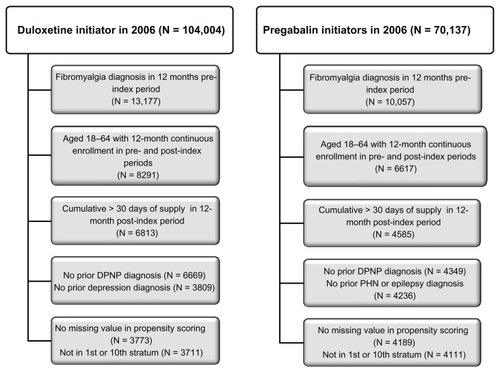

As in the previous study,Citation35,Citation36 propensity score stratification was applied to construct duloxetine and pregabalin cohorts with similar demographics, health plan types, geographic regions, comorbid medical conditions, prior health care costs, and prior select medication history (ie, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sleep and antianxiety medications, skeletal muscle relaxants, dopamine agonists, topical agents, and 5-HT3 antagonists). A logistic regression predicting the probability of initiating duloxetine versus pregabalin was estimated first. The predicted probability of duloxetine initiation was ranked for all individuals from highest to lowest into 10 strata, so that cross-cohort differences in all intend-to-adjusted variables were not statistically significant at stratum 2 through 9 (based on paired two-tailed t-tests for means and proportions). Duloxetine and pregabalin patients in the top or bottom stratum were further excluded because they had the most different characteristics. The sample selection flow chart is described in . We started with 104,004 duloxetine initiators and 70,137 pregabalin initiators in 2006. The final study sample included 3711 duloxetine patients and 4111 pregabalin patients, respectively.

Common reasons for inpatient and outpatient services

For both duloxetine and pregabalin patients, Urix’s RiskSmart software was used to identify all the medical conditions captured in claims collected over the 12-month post-index period. This RiskSmart software applies a comprehensive disease classification system that automatically organizes comprehensive ICD-9-CM codes (more than 15,000) recorded in administrative claims database into 781 homogeneous clinical categories (DxGroups).Citation36 Using the same software, all claims from inpatient admissions, outpatient hospital services, physician office services, and emergency room were processed separately. DxGroups generated from each process were used to identify reasons leading to inpatient admissions, physician office visits, outpatient hospital visits, and emergency room visits, respectively. For all claims collected from physician office visits, primary care (eg, family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrician) versus specialty care (eg, pain medicine and other non-primary care medicine fields) visits were further separated based on physician specialties. Claims from primary versus specialty care visits were examined respectively, and DxGroups were used to identify the reasons leading to each type of visit.

Analysis

For patients in the duloxetine and pregabalin cohorts, the propensity score-adjusted demographics and health care costs (total, inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy) over the 12-month pre-index period were examined to show the similarities between groups.Citation35 Propensity score-adjusted health care costs over the 12-month post-index period were compared between the duloxetine and pregabalin patients to identify what contributed most to the cross-cohort cost differences.Citation35

Mapping the first diagnosis from each inpatient, outpatient hospital, physician office visit, and emergency room claim captured over the 12-month post-index period into a DxGroup category, we examined the most common reasons for inpatient admissions, physician office visits, outpatient hospital visits, and emergency room visits, respectively. Using physician specialty to distinguish further between primary versus specialty care visits for all the claims submitted for physician office visits, the first diagnosis from each claim was mapped into a DxGroup category to analyze the most common reasons leading to primary versus specialty care visits. The prevalence per 10,000 persons of inpatient admissions, outpatient hospital visits, physician office visits, emergency room visits, and primary and specialty care visits were compared between the duloxetine and pregabalin cohorts. Logistic regression was used to assess further the incremental contribution of duloxetine versus pregabalin initiation (odds ratio from the logistic regression) to inpatient admissions, outpatient hospital visits, physician office visits, emergency room visits, and primary and specialty care visits, controlling for cross-cohort differences. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

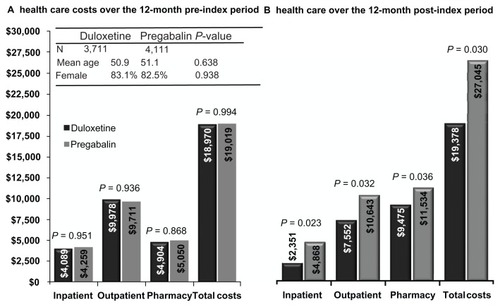

Per study design, both duloxetine and pregabalin patients had similar demographics (mean age 51 years, 83% females) and health care costs over the 12-month pre-index period (). However, duloxetine patients had significantly lower total costs ($19,378 versus $27,045) than pregabalin patients during the 12-month post-index period, with most of the cost difference from outpatient services ($7,552 versus $10,643) followed by inpatient services ($2351 versus $4868, all P values <0.05).

The most common reasons for inpatient admissions are presented in for both the duloxetine and pregabalin patients. Both cohorts shared eight of the 10 most common reasons, and three of the top five reasons were the same, ie, intervertebral disc disorders (herniated, prolapsed, degenerated disc), osteoarthritis of lower leg (knee), and chest pain. Compared with the pregabalin patients, duloxetine patients were less likely to be hospitalized due to an intervertebral disc disorder, major depressive disorder, or spondylosis and allied disorders, eg, osteoarthritis of spine (odds ratios 0.443, 0.808, and 0.355, respectively), but more likely to be admitted to hospital due to intestinal obstruction (odds ratio 3.229, all P < 0.05).

Table 1 Top reasons for inpatient admissions in the 12-month post-index period

summarizes the leading reasons for physician office visits by patients in both the duloxetine and pregabalin cohorts. All top reasons were shared, with physician office visits due to soft tissue disorders (eg, tendonitis bursitis, muscle tissue disorder) being the most common reason in both cohorts, followed by nonspecific backache/other back/neck pain (NB/OB/NP) disorders. Controlling for cross-cohort differences, duloxetine patients were less likely than pregabalin patients to have physician office visits due to NB/OB/NP or an intervertebral disc disorder (odds ratios 0.689 and 0.622, respectively, both P < 0.05).

Table 2 Top reasons for physician office visits in the 12-month post-index period

Eight of the 10–11 most common reasons for outpatient hospital visits were shared by both the duloxetine and pregabalin cohorts (). The top three reasons were the same, with other general symptoms being the most common reason followed by soft tissue and NB/OB/NP disorders. Controlling for cross-cohort differences, duloxetine patients were more likely to make an outpatient visit due to other general symptoms (odds ratios 1.428), but less likely to make an outpatient visit due to asthma (except chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) or upper limb neuropathy, eg, carpal tunnel syndrome (odds ratios 0.914 and 0.491, respectively, all P < 0.05).

Table 3 Top reasons for outpatient hospital visits in the 12-month post-index period

shows the most common reasons for emergency room visits by patients in the duloxetine and pregabalin cohorts. Both cohorts shared all the leading reasons, with the top eight being the same. Chest pain was the leading reason for emergency room visits, with the prevalence rate per 10,000 being 1347 for duloxetine and 1404 for pregabalin. The duloxetine cohort had lower raw emergency room rates than the pregabalin cohort (columns 2 and 4) for all reasons listed except abdominal/pelvic symptoms, contusion/superficial injury, or migraine headaches. However, none of the predictors of any emergency room visit controlling for cross-cohort differences were statistically significant.

Table 4 Top reasons for emergency room visits in the 12-month post-index period

Nine of the 10 most common reasons for primary care visits were the same for both the duloxetine and pregabalin patients, with soft tissue disorders being the leading one (). The prevalence of primary care visits due to essential hypertension (duloxetine 2375 per 10,000, third ranking; pregabalin 2366 per 10,000, fourth ranking) or NB/OB/NP (duloxetine 1940 per 10,000, seventh ranking; pregabalin 2570 per 10,000, second ranking) disorders was high. Controlling for cross-cohort differences, duloxetine patients were more likely to make primary care visits due to soft tissue disorders, essential hypertension, other general symptoms, or malaise and fatigue, including chronic fatigue syndrome (odds ratios 1.115, 1.160, 1.142, and 1,227, respectively) than pregabalin patients, but less likely to seek primacy care due to NB/OB/NP or type 2 diabetes without complications (odds ratios 0.836 and 0.833, respectively, all P < 0.05).

Table 5 Top reasons for primary care visits in 12-month post-index period

shows the leading reasons for specialty care visits for patients in both the duloxetine and pregabalin cohorts. Nine of the main reasons for specialty care visits were the same in both cohorts, and soft tissue disorders were the most common reason leading to a specialty care visit. The duloxetine cohort had lower raw specialty care rates than the pregabalin cohort for all reasons listed, except screening for a malignant neoplasm or screening, observation, and special examinations. Controlling for cross-cohort differences, duloxetine patients were more likely to make a specialty care visit due to screening for a malignant neoplasm (odds ratio 1.132), but were less likely to attend to specialty care due to a soft tissue, NB/OB/NP, or intervertebral disc disorder, or for spondylosis or an allied disorder (odds ratios 0.835, 0.693, 0.629, and 0.719, respectively, all P < 0.05).

Table 6 Top reasons for specialty care visits in the 12-month post-index period

Discussion

Using a large US administrative claims database on similar commercially insured patients with fibromyalgia who initiated duloxetine or pregabalin in 2006, this study was the first to use a comprehensive disease classification to examine the most common reasons leading to inpatient admissions, physician office visits, outpatient hospital visits, emergency room visits, and primary care and specialty care visits. Although duloxetine patients had significantly lower total health care costs than pregabalin patients over the 12-month post-index periods, with most of the cost difference from outpatient services followed by inpatient services (for a detailed discussion, please see our previous publication),Citation35 patients in both cohorts shared eight or nine of the top 10 most common reasons for inpatient admissions and outpatient visits. The top three leading reasons for inpatient admissions and outpatient hospital visits, top five reasons for physician office visits, and top eight reasons for emergency room visits were the same for both duloxetine and pregabalin patients.

This study had several interesting findings. First, soft tissue disorders were the leading reason for physician office visits, including both primary and specialty care visits; it was also one of the most common reasons for outpatient hospital visits (ranked second for duloxetine, and third for pregabalin) and emergency room visits (seventh ranking for both duloxetine and pregabalin). Controlling for cross-cohort differences, duloxetine patients were more likely to have a primary care visit due to soft tissue disorders than pregabalin patients. Given its high prevalence in various health care encounters and different use of primary care versus specialty care setting, future research may need to explore further how soft tissue disorders are treated in real-world practice when managing fibromyalgia.

Second, the prevalence rate for NB/OB/NP was very high across the care settings, ie, the second most common reason for physician office visits, the third (duloxetine) and second (pregabalin) leading reason for outpatient hospital visits, the seventh (duloxetine) and second (pregabalin) most common reason for primary care visits, and the fourth (duloxetine) and second (pregabalin) leading reason for specialty care visits. Controlling for cross-cohort differences, duloxetine patients were less likely to go to the physician’s office in either the primary or specialty care setting due to NB/OB/NP than were pregabalin patients. The higher physician office use of NB/OB/NP among pregabalin patients may impact health care costs, and further research might be warranted.

Third, intervertebral disc disorder was the leading cause of inpatient admissions for both duloxetine and pregabalin patients, and its prevalence was also high for outpatient visits (duloxetine sixth, pregabalin fourth), specialty care (duloxetine seventh, pregabalin fourth), and physician office visits (duloxetine eleventh, pregabalin sixth). Controlling for cross-cohort differences, duloxetine patients were less likely than pregabalin patients to go to each of the care settings mentioned above, except for outpatient hospital visits. Why intervertebral disc disorder is managed differently between duloxetine and pregabalin patients and how the different use of health care systems may impact health care costs needs to be examined in future studies.

Lastly, chest pain was the most common reason for emergency room visits by patients in both cohorts, and it was also the main reason for inpatient admissions (third and second for duloxetine and pregabalin, respectively), and specialty care visits (ninth for both duloxetine and pregabalin). The prevalence was similar between the cohorts, and no statistically significant result was found controlling for cross-cohort differences. Because inpatient admissions and emergency room visits are costly, managing the top reasons leading to emergency room visits as well as hospitalization effectively may potentially reduce overall health care costs.

This study has several limitations. First, because of its retrospective design, this analysis can only describe the different reasons leading to inpatient and outpatient care. What caused the different use in the different care settings could be not identified. Second, ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes were used to identify all medical conditions captured in the administrative claims database. Therefore, medical conditions not recorded anywhere in the database analyzed here were not recognized. Third, all patients included were from a large, geographically diverse commercial population covered by large employer-sponsored private health insurance, so findings from this study may not be generalizable to other populations with different characteristics. Fourth, non-pharmacological management for fibromyalgia was not addressed in this study, so its impact on inpatient and outpatient care is unknown. Finally, all patients were required to have continuous enrollment during the 12-month pre-index and post-index periods. Any patients who dropped out of the health plan anytime before or after the index date were not included.

Conclusion

Among similar commercially insured patients with fibromyalgia, those initiated on duloxetine had significantly lower health care costs over the 12-month post-index period than those who initiated pregabalin. The leading reasons for inpatient or outpatient visits were also somewhat different.

Disclosure

Data from this study were presented in poster form at the European International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research 2011 meeting held in Madrid, Spain.

References

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin DiseasesFibromyalgia1999 Available from: http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Fibromyalgia/default.aspAccessed May 5, 2009

- TopbasMCakirbayHGulecHAkgolEAkICanGThe prevalence of fibromyalgia in women aged 20–64 in TurkeyScand J Rheumatol200534214014416095011

- WeirPTHarlanGANkoyFLThe incidence of fibromyalgia and its associated comorbidities: a population-based retrospective cohort study based on International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codesJ Clin Rheumatol200612312412816755239

- TodaKThe prevalence of fibromyalgia in Japanese workersScand J Rheumatol200736214014417476621

- MasAJCarmonaLValverdeMRibasBPrevalence and impact of fibromyalgia on function and quality of life in individuals from the general population: results from a nationwide study in SpainClin Exp Rheumatol200826451952618799079

- National Fibromyalgia AssociationPrevalence of fibromyalgia, 2009 Available from: http://www.fmaware.org/site/PageServer?pagename=fibromyalgia_affectedAccessed May 5, 2009

- Wrong DiagnosisPrevalence and incidence of fibromyalgia2009 Available from: http://www.wrongdiagnosis.com/f/fibromyalgia/stats.htmAccessed May 5, 2009

- WolfeFPetriMAlarconGSFibromyalgia, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and evaluation of SLE activityJ Rheumatol2009361828819004039

- WolfeFHawleyDJGoldenbergDLRussellIJBuskilaDNeumannLThe assessment of functional impairment in fibromyalgia (FM): Rasch analyses of 5 functional scales and the development of the FM Health Assessment QuestionnaireJ Rheumatol20002781989199910955343

- WolfeFSmytheHAYunusMBThe American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria CommitteeArthritis Rheum19903321601722306288

- BrancoJCBannwarthBFaildeIPrevalence of fibromyalgia: a survey in five European countriesSemin Arthritis Rheum201039644845319250656

- BannwarthBBlotmanFRoue-Le LayKCaubereJPAndreETaiebCFibromyalgia syndrome in the general population of France: a prevalence studyJoint Bone Spine200976218418718819831

- SchochatTRaspeHElements of fibromyalgia in an open populationRheumatology (Oxford)200342782983512730531

- BazelmansEVercoulenJHGalamaJMvan WeelCvan der MeerJWBleijenbergGPrevalence of chronic fatigue syndrome and primary fibromyalgia syndrome in The NetherlandsNed Tijdschr Geneeskd19971413115201523 Dutch9543739

- WolfeFHawleyDJWilsonKThe prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic diseaseJ Rheumatol1996238140714178856621

- SardiniSGhirardiniMBetelemmeLArpinoCFattiFZaniniFEpidemiological study of a primary fibromyalgia in pediatric ageMinerva Pediatr19964812543550 Italian9091773

- WolfeFRossKAndersonJRussellIJHebertLThe prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general populationArthritis Rheum199538119287818567

- BuskilaDNeumannLHershmanEGedaliaAPressJSukenikSFibromyalgia syndrome in children – an outcome studyJ Rheumatol19952235255287783074

- PaganoTMatsutaniLAFerreiraEAMarquesAPPereiraCAAssessment of anxiety and quality of life in fibromyalgia patientsSao Paulo Med J2004122625225815692719

- OzcetinAAtaogluSKocerEEffects of depression and anxiety on quality of life of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, knee osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia syndromeWest Indian Med J200756212212917910141

- TheadomACropleyMHumphreyKLExploring the role of sleep and coping in quality of life in fibromyalgiaJ Psychosom Res200762214515117270572

- SchoofsNBambiniDRonningPBielakEWoehlJDeath of a lifestyle: the effects of social support and healthcare support on the quality of life of persons with fibromyalgia and/or chronic fatigue syndromeOrthop Nurs200423636437415682879

- VerbuntJAPernotDHSmeetsRJDisability and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgiaHealth Qual Life Outcomes20086818211701

- TanderBCengizKAlayliGIlhanliICanbazSCanturkFA comparative evaluation of health related quality of life and depression in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome and rheumatoid arthritisRheumatol Int200828985986518317770

- SalaffiFSarzi-PuttiniPGirolimettiRAtzeniFGaspariniSGrassiWHealth-related quality of life in fibromyalgia patients: a comparison with rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population using the SF-36 health surveyClin Exp Rheumatol2009275 Suppl 56S67S7420074443

- CarvilleSFArendt-NielsenSBliddalHEULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndromeAnn Rheum Dis200867453654117644548

- GuymerEKLittlejohnGOFibromyalgia. Diagnosis and managementAustralas Chiropr Osteopathy2002102818417987178

- SumptonJEMoulinDEFibromyalgia: presentation and management with a focus on pharmacological treatmentPain Res Manag200813647748319225604

- BuckhardtCSGoldenbergDCroffordLGuideline for the Management of Fibromyalgia Syndrome Pain in Adults and ChildrenAPS Clinical Practice Guideline Series No 4Glenview, ILAmerican Pain Society2005

- HauserWThiemeKTurkDCGuidelines on the management of fibromyalgia syndrome – a systematic reviewEur J Pain201014151019264521

- ForsethKKGranJTManagement of fibromyalgia: what are the best treatment choices?Drugs200262457759211893227

- BrosseauLWellsGATugwellPOttawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for aerobic fitness exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 1Phys Ther200888785787118497301

- BrosseauLWellsGATugwellPOttawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for strengthening exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 2Phys Ther200888787388618497302

- CroffordLJPain management in fibromyalgiaCurr Opin Rheumatol200820324625018388513

- ZhaoYSunPWatsonPMitchellBSwindleRComparison of medication adherence and healthcare costs between duloxetine and pregabalin initiators among patients with fibromyalgiaPain Pract201011320421620807351

- ZhaoYAshASEllisRPSlaughterJPDisease burden profiles: an emerging tool for managing managed careHealth Care Manag Sci20025321121912363048