Abstract

Background

Post-surgical pain is prevalent in children, yet is significantly understudied. The goals of this study were to examine gender differences in pain outcomes and pain-related psychological constructs postoperatively and to identify pain-related psychological correlates of acute post-surgical pain (APSP) and predictors of functional disability 2 weeks after hospital discharge.

Methods

Eighty-three children aged 8–18 (mean 13.8 ± 2.4) years who underwent major orthopedic or general surgery completed pain and pain-related psychological measures 48–72 hours and 2 weeks after surgery.

Results

Girls reported higher levels of acute postoperative anxiety and pain unpleasantness compared with boys. In addition, pain anxiety was significantly associated with APSP intensity and functional disability 2 weeks after discharge, whereas pain catastrophizing was associated with APSP unpleasantness.

Conclusion

These results highlight the important role played by pain-related psychological factors in the experience of pediatric APSP by children and adolescents.

Introduction

Post-surgical pain is prevalent in pediatric populations, yet is significantly understudied. Citation1 Research has shown that between 15%Citation2 and 60%Citation3–Citation7 of children report moderate to severe acute postoperative pain (APSP). Prospective studies of pediatric APSP have shown that preoperative anticipatory anxiety, younger age, and lower anticipatory distress before surgery predict higher APSP intensity on the day of surgery,Citation8,Citation9 and negative affect and pessimistic expectations about surgery predict functional disability one week after oral surgery.Citation10 In addition, studies conducted postoperatively have found that coping strategies, depression, and self-efficacy correlate with acute pain intensity scores following surgery among adolescents.Citation11–Citation14

Gender differences in APSP and psychological constructs

Clinical studies of pediatric pain reveal significant gender differences in the experience and expression of pain, with acute and chronic pain being more prevalent among girls.Citation15 Girls with chronic pain reported higher pain intensity and frequency, higher health care utilization, medication intake, and utilization of nonpharmacological interventions, as well as a higher level of school absenteeism compared with boys with chronic pain.Citation16–Citation18 Girls have also reported higher levels of pain-related psychological constructs, such as anxiety sensitivity and pain catastrophizing.Citation19

Gender differences have been found in some studies of perioperative pain and anxiety. For example, girls reported higher levels of preoperative anxiety and expected to experience more intense postoperative pain than did boys; girls also reported higher levels of postoperative pain intensity. Citation5 Gender also served as a moderator of the relationship between preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain, such that preoperative anxiety was associated with higher levels of postoperative pain intensity in girls but not in boys.Citation5 In contrast, no significant gender differences were found in APSP intensity scores among children and adolescents after spinal fusionCitation20 or after minor or medium surgical procedures.Citation21 The role of gender in APSP and pain-related psychological constructs is thus unclear.

Perioperative anxiety

A significant amount of work has been done on the impact of perioperative anxiety on perioperative pain and behavior change. More specifically, children report higher levels of anxiety following surgery compared with the preoperative period, and higher levels of postoperative anxiety are associated with higher levels of pain intensity in the days following surgery.Citation22 Preoperative anxiety was also found to predict higher pain intensity over the first 2 weeks after surgery, higher consumption of codeine and acetaminophen, and sleep difficulties.Citation23

While anxiety appears to be an important construct in pediatric APSP, the research suggests that compared with general measures of anxiety, pain-specific constructs (eg, pain anxiety, pain catastrophizing) account for a higher proportion of variance in pain outcomes.Citation24 Pain anxiety refers to the cognitive (eg, difficulties concentrating when in pain), emotional (eg, fear of pain-related consequences or pain amplification), physiological (eg, increased heart rate), and behavioral (eg, pain avoidance) reactions associated with the experience and/or anticipation of pain. Pain catastrophizing refers to the rumination, feeling of helplessness, and magnification of the experience of pain.Citation25,Citation26 Clinical and community-based studies have shown that pain anxiety and pain catastrophizing are associated with pain-related disability and pain severity in children.Citation27,Citation28 However, the role of pain-related anxiety in the experience of pediatric APSP has not yet been examined.Citation29

The main goals of this study were to examine gender differences in pain outcomes and pain-related psychological constructs postoperatively and identify pain-related psychological correlates of acute post-surgical pain in the first 2 days after surgery and the predictors of functional disability 2 weeks after hospital discharge in a sample of children and adolescents undergoing major surgery.

Materials and methods

Participants and recruitment

Children undergoing general surgical procedures (ie, thoracotomy, thoracoabdominal surgery, a Nuss or Ravitch surgical procedure (for pectus anomalies), sternotomy, laparotomy, ostomy) or orthopedic surgery (ie, scoliosis, osteotomy, tibial/femoral plate insertion, open hip reduction, hip capsulorrhaphy) and who were aged 8–18 years were eligible to participate in this study. Exclusion criteria were having a developmental or cognitive delay, having cancer, or not being fluent in written and/or spoken English.

Questionnaires

Child Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale

The Child Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (CPASS)Citation30 is a 20-item scale for children, and is adapted from the adult PASS-20.Citation31 For each statement, children are asked to rate the extent to which they think, act, or feel a certain way on a scale from 0 (“never think, act or feel that way”) to 5 (“always think, act, or feel that way”). Total scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of pain anxiety. The CPASS is composed of four subscales, ie, cognitive, escape/avoidance, fear, and physiological anxiety. The CPASS showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.90) in a community sample of childrenCitation30 as well as in the present study (α = 0.92–0.96).Citation32 In addition, the CPASS correlated more strongly with pain catastrophizing (r = 0.63) and anxiety sensitivity (r = 0.60) than with general anxiety (r = 0.44) (suggesting adequate construct validity) and was significantly associated with how often children reported pain.Citation30

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC-10)Citation33 is a short, 10-item version of the 39-item Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children. The MASC-10 items, which tap physiological symptoms, social anxiety, harm avoidance, and separation/panic, are summed to form a global anxiety symptom score. Children are asked to rate the extent to which each of the 10 statements is true about them on a scale from 0 (“never true about me”) to 3 (“often true about me”). Total scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety. The MASC-10 has adequate internal consistency (α = 0.60–0.85), good test-retest reliability (r = 0.79–0.93), good convergent validity (high correlation with the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale), and good discriminant validity (absence of a significant correlation with the Children’s Depression Inventory).Citation33 Internal consistency for the present sample was adequate (α = 0.73–0.84).

Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index

The Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index (CASI)Citation34 assesses the extent to which the respondent interprets anxiety-related symptoms (eg, increased heart rate, feeling nauseated) as indicators of potentially harmful somatic, psychological, and/or social consequences.Citation35 The scale is composed of 18 items such as “It scares me when my heart beats fast” and “It scares me when I feel like I’m going to throw up”. Items are rated on a scale ranging from 1 (“none”) to 3 (“a lot”). Total scores range from 18 to 54, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety sensitivity. The CASI has good internal consistency (α = 0.87) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.76) as well as adequate convergent and discriminant validity.Citation34 Internal consistency for the present study was excellent (α = 0.87–0.93).

Pain Catastrophizing Scale-Children

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale-Children (PCS-C)Citation36 is a 13-item self-report measure assessing the extent to which children worry, amplify, and feel helpless about their current or anticipated pain experience.Citation36 The scale was modified for use with children based on the adult PCS.Citation25 For each item, children are asked to rate, on a scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”), “how strongly they experience this thought” when they have pain. Total scores range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating higher levels of pain catastrophizing. The PCS-C comprises three subscales, ie, rumination, magnification, and helplessness. Preliminary results suggest that the PCS-C has good internal consistency (α = 0.90), and correlates highly with pain intensity (r = 0.49) and disability (r = 0.50).Citation36 Internal consistency for the present study was excellent (α = 0.93).

Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC)Citation37 is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. The questionnaire measures six broad symptom areas, including depressed mood, guilt/worthlessness, helplessness/hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbance. For each item, participants indicate the extent to which they have felt this way in the past week, using a scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“a lot”). Total scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptomatology. The CES-DC has good internal consistency (α = 0.89) and good convergent validity (and is significantly correlated with the Child Trait Checklist, the Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory, and the Children’s Global Assessment Scale).Citation38 Internal consistency for the present study was excellent (α = 0.90–0.91).

Functional Disability Inventory

The Functional Disability Inventory (FDI)Citation39 is a 15-item scale that assesses the extent to which children experience difficulties in completing specific tasks (eg, “Walking to the bathroom”, “Eating regular meals”, and “Being at school all day”). Typically, the FDI is used as a five-point Likert scale and yields total scores ranging from 0 to 60. Inadvertently, the FDI in the present study was measured using a four-point Likert scale and omitted the original “2” (“some trouble”). Children in this study rated each item on a scale from 0 to 3, ie, (0, “no trouble”; 1, “a little trouble”; 2, “a lot of trouble”; and 3, “impossible”), yielding total scores ranging from 0 to 45. The FDI has excellent internal consistency (α = 0.86–0.91) and good test-retest reliability at 2 weeks (r = 0.74) and 3 months (r = 0.48).Citation39 The FDI has been used with many pediatric populations, including children with chronic painCitation40–Citation42 and post-surgical pain.Citation10 Internal consistency for the present study was excellent (α = 0.83–0.89).

Numerical Rating Scale for pain intensity and pain unpleasantness

The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) is a verbally administered scale that measures pain intensity (“How much pain do you feel right now?”). The NRS was also used to measure pain unpleasantness (“How unpleasant/horrible/yucky is the pain right now?”). The end points represent the extremes of the pain experience. Because there are no agreed upon NRS anchors for measuring pain in children and adolescents,Citation43 the following anchors were used in the present study: for pain intensity, 0 = “no pain at all” to 10 = “worst possible pain”; for pain unpleasantness, 0 = “not at all unpleasant/horrible/yucky” to 10 = “most unpleasant/horrible/yucky feeling possible”. The NRS for pain intensity has been validated as an APSP measure in children aged seven to 17 years, and correlated highly with the Visual Analog Scale (r = 0.89) and the Faces Pain Scale-Revised (r = 0.87).Citation44

Preoperative pain experience

The children were asked retrospectively (48–72 hours after surgery), to answer the following question: “Before surgery, how much pain did you have in general?” using one of four verbal descriptors: no pain; a little bit of pain; a medium amount of pain; or a lot of pain.

Hospital chart review

The following information was collected from the children’s hospital charts: preoperative information (eg, ongoing pain problems, regular pain medications, previous surgery), perioperative information (eg, type of procedure, length of surgery) and postoperative information (eg, pain medication on the first day after surgery).

Procedure

The study was reviewed and approved by the research ethics boards of the Hospital for Sick Children and York University. Nurses not involved in the research project approached potential participants 48–72 hours after surgery to assess their interest in learning about this research. Interested children and one of their parents were then approached by a research team member. Written parental consent and consent or assent from the children were then obtained. A member of the research team then read to the child the CPASS, PCS-C, CASI, MASC-10, CES-DC, FDI, NRS-Pain Intensity (NRS-I), NRS-Pain Unpleasantness (NRS-U), and the Preoperative Pain Experience questionnaire and recorded their responses to each item. Potential order and fatigue effects were minimized by randomizing the order of administration of questionnaires within participants (http://www.randomization.com). Telephone follow-ups were done approximately 2 weeks after discharge from hospital by a research assistant who verbally administered the CPASS, FDI, NRS-I, and NRS-U to the children. Parents also completed measures, and these results will be presented in a separate paper.

Data analysis

Data screening

Testing of skewness and the significance of kurtosis (estimate/standard error > 3) revealed non-normality of pain intensity (NRS-I) and pain unpleasantness (NRS-U) 2 weeks after discharge from hospital. Non-normality of the distribution of these two variables was addressed by squareroot transformation [NRS-I(2)t, NRS-U(2)t].

Descriptive statistics

Univariate analysis of variance was used to examine differences in pain intensity (model 1) and pain unpleasantness (model 2) scores 48–72 hours after surgery and 2 weeks after discharge (NRS-I, model 3; NRS-U, model 4) across the different types of surgical procedure. In addition, the Pearson Chi-square test was used to examine gender differences across types of surgical procedures.

Two-tailed t-tests with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.017) were used to examine differences in NRS-I and NRS-U scores 48–72 hours after surgery and analgesic consumption (in morphine equivalents) on the first day following surgery in children who had prior surgical experience versus those who did not. In addition, a series of three two-tailed t-tests with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.017) was used to examine differences in NRS-I(2)t, NRS-U(2)t, and functional disability scores [FDI(2)] in children who had prior surgical experience versus those who did not.

A multivariate analysis of variance was used to examine whether or not prior surgical experience was associated with children’s self-report on the CPASS, PSC-C, CASI, MASC-10, and CES-DC at 48–72 hours after surgery. A significant omnibus effect on the multivariate analysis of variance was followed by an examination of the univariate tests.

Gender differences in postoperative pain-related psychological constructs

Two-tailed t-tests were used to look for any gender differences in psychological measures and pain outcomes 48–72 hours and 2 weeks after surgery.

Correlates of APSP and predictors of functional disability

Linear regression analyses examined whether pain-related psychological factors were associated with pain intensity [NRS-I(0)] and pain unpleasantness [NRS-U(0)] 48–72 hours after surgery. In each model, age, gender, and analgesic consumption (mg/kg in morphine equivalentsCitation45) were entered in the first step, followed by CES-DC(0) and MASC-10(0) in order to control for depression and anxiety. In the third step, CPASS(0), PCSC(0), and CASI(0) were entered stepwise in the model. Alpha levels for the overall models were adjusted (α = 0.025) using Bonferroni correction.

Linear regression analyses examined whether pain-related psychological factors predicted pain intensity [NRS-I(2)t], pain unpleasantness [NRS-U(2)t], and functional disability (FDI[2]) 2 weeks after discharge from hospital. In each model, age, gender, and analgesic consumption (mg/kg in morphine equivalents) were entered first, followed by CES-DC(0) and MASC(0) in order to control for depression and anxiety. In the third step, CPASS(0), PCSC(0), and CASI(0) were entered stepwise into the model. Alpha levels for the overall models were adjusted (α = 0.017) using Bonferroni correction.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Sample size estimation

The sample size was estimated a priori using G*Power version 3.1.Citation46 A sample size of 50 participants would be required for a Pearson Chi-square test to detect a medium to large effect size (w = 0.40) with α = 0.05, power = 80%, and df = 1. Seventy-eight participants would be required to ensure α = 0.05 and power = 80%, with a medium to large effect size two-tailed independent samples t-test. Sample size analysis showed that 58 participants would be required for a one-way multivariate analysis of variance, with five response variables and two groups in the independent variable to ensure α = 0.05 and power = 80%. A linear regression analysis with α = 0.025 and power = 80%, using seven predictors and a medium to large effect size (f2 = 0.25), would require a sample size of 76 participants. Thus, allowing for attrition, we attempted to recruit a total sample size of 80 participants.

Results

Recruitment

Recruitment took place between July 2008 and September 2010. Eighty-three children/parents (56 [67.5%] females) aged 8–18 (mean 13.8 ± 2.4) years (girls 14.0 ± 2.3 years; boys 13.5 ± 2.6 years) participated in the study, and 69 (83%) completed the telephone follow-up approximately 2 weeks after discharge from hospital (mean 15.6 ± 2.15 days). Fourteen participants could not be reached or were away on vacation during the time of follow-up. Details of the recruitment process are shown in .

Table 1 Recruitment process

Descriptive statistics

The majority of children in this sample self-identified as Caucasian (n = 53, 64%) and as speaking English as their first language at home (n = 74, 89%). Forty-two children underwent spinal fusion for scoliosis (50.6%), 25 underwent osteotomy (30.1%), eight (9.6%) underwent a Nuss (n = 5) or Ravitch (n = 3) procedure, seven underwent (8.4%) laparotomy, and one child had a thoracotomy. Approximately half of the children (n = 39, 47%) had previously undergone a surgical procedure in the past (mean number of surgeries = 2.0 ± 1.6, range 1–7), while this was a novel experience for 44 children (53%). The majority of children (80.7%) reported retrospectively that they had “no pain” or “a little bit of pain” before the surgery.

The mean duration of surgery was 317.5 ± 141.3 minutes and the mean time spent in the post anesthesia care unit was 181.2 ± 143.3 minutes. Details of analgesics used intraoperatively, in the post anesthesia care unit, and on the first day after surgery are shown in . The mean morphine-equivalent analgesic consumption on the day following surgery was 1.21 ± 1.02 mg/kg (62.81 ± 57.6 mg).

Table 2 Peri-operative Information

Significant differences were not found in pain intensity or pain unpleasantness scores 48–72 hours after surgery and 2 weeks after discharge from hospital across the different types of surgical procedures. Chi-square testing revealed significant gender differences across the types of surgical procedures (χ2 = 23.25, P < 0.001), in that fewer boys had surgery for scoliosis than expected by chance and more boys had a Nuss or Ravitch procedure than expected by chance.

Differences associated with prior surgery

Significant differences were not found in pain intensity (P = 0.574) or pain unpleasantness (P = 0.995) 48–72 hours after surgery or in morphine-equivalent analgesic consumption (mg/kg) on the day after surgery (P = 0.584) in children who had prior surgical experience versus those who did not. In addition, significant differences were not found between children who had prior surgical experience versus those who did not on measures of pain intensity (P = 0.433), pain unpleasantness (P = 0.689), or functional disability levels (P = 0.632) 2 weeks after discharge from hospital.

Results of the multivariate analysis of variance at 48–72 hours after surgery showed an overall significant effect [Pillai’s trace = 0.198, F(5,74) = 3.66, P = 0.005]. Examination of the univariate tests indicated that children who had never previously undergone surgery scored significantly higher on anxiety sensitivity [mean CASI score 35.07 ± 6.5, (F(1,78) = 6.24, P = 0.015] and general anxiety [mean MASC-10 score 13.20 ± 4.6, F(1,78) = 7.40, P = 0.008] than children who had undergone surgery in the past (mean CASI score 31.14 ± 7.6; mean MASC-10 score 10.05 ± 5.8).

Gender differences in postoperative pain-related psychological constructs

Mean values for boys and girls on the relevant psychological and pain measures are shown in . Significant gender differences were observed on anxiety sensitivity [mean difference of 4.32 in CASI score, t(1,81) = 2.59, P = 0.011], general anxiety [mean difference of 3.30 in MASC-10 score, t(1,79) = 2.73, P = 0.008], and pain unpleasantness [mean difference of 1.28 in NRS-U score, t(1,81) = 2.01, P = 0.048] 48–72 hours after surgery, such that girls scored higher compared with boys on these measures. Girls also scored significantly higher on functional disability [mean difference of 4.83, t(1,67) = 2.20, P = 0.031] 2 weeks after discharge compared with boys, but this difference was no longer significant when taking into account only children who reported experiencing pain 2 weeks after discharge from hospital (P = 0.090). There were no gender differences in morphine-equivalent analgesic consumption on the first day after surgery (P = 0.194).

Table 3 Mean (standard deviation) of pain and related psychological variables for boys, girls, and the total sample when measured 48–72 hours after surgery and 2 weeks after discharge

Correlates of APSP and predictors of functional disability

Results of the linear regression analyses 48–72 hours after surgery showed that age (β = 0.26, P = 0.030), depression (CES-DC, β = 0.36, P = 0.025), anxiety (MASC-10, β = −0.38, P = 0.027) and pain anxiety (CPASS, β = 0.51, P = 0.001) were significantly associated with pain intensity [NRS-I, F(6;49) = 5.97, adjusted R2 = 0.35, R2 change = 0.15, P < 0.001] and that morphine-equivalent (mg/kg) analgesic consumption (β = −0.27, P = 0.042) and pain catastrophizing (PCS-C, β = 0.32, P = 0.042) were significantly associated with pain unpleasantness [NRS-U, F(6;52) = 3.05, adjusted R2 = 0.18, R2 change = 0.06, P = 0.012]. Details of the regression analyses are presented in .

Table 4 Pain-related psychological variables (48–72 hours after surgery) associated with APSP (48–72 hours after surgery) intensity and unpleasantness using linear regression analysis

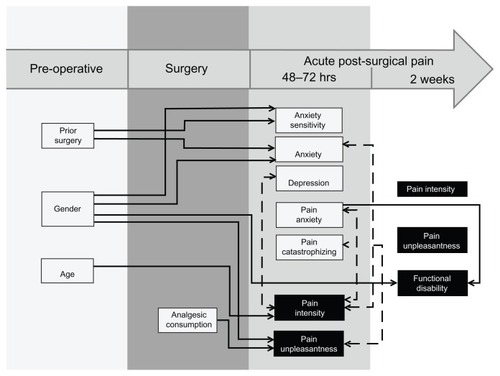

Results of the linear regression analyses 2 weeks after discharge from hospital failed to show any significant predictors (measured 48–72 hours after surgery) of pain intensity [NRS-It, F(5;43) = 1.95, P = 0.11] or pain unpleasantness [NRS-Ut, F(5;43) = 1.76, P = 0.15]. However, pain anxiety (CPASS, β = 0.33, P = 0.013) measured 48–72 hours after surgery significantly predicted levels of functional disability 2 weeks after discharge from hospital [F(6;42) = 5.32, adjusted R2 = 0.35, R2 change = 0.09, P < 0.001]. Details of the regression analyses are shown in . A graphic summary of the results is presented in .

Figure 1 Summary of results showing that children who were surgery-naïve had higher levels of anxiety sensitivity and general anxiety compared with children who had undergone surgery in the past.

Table 5 Pain-related psychological variables (48–72 hours after surgery) associated with APSP (2 weeks after discharge) intensity and unpleasantness and functional disability using linear regression analysis

Discussion

The study objectives were to examine gender differences in pain outcomes and pain-related psychological constructs postoperatively and to identify pain-related psychological correlates of APSP and functional disability in a sample of children and adolescents undergoing major surgery.

Gender differences in pain-related psychological constructs postoperatively and APSP

Significant gender differences were found in pain unpleasantness, but not in pain intensity scores, at 48–72 hours after surgery. This suggests that girls are more vulnerable to the affective, but not to the sensory aspect, of APSP compared with boys. This gender difference had dissipated 2 weeks after discharge from hospital, suggesting that after time has elapsed from the painful event, girls and boys tended to react affectively in an increasingly similar fashion. The gender differences observed in the affective component of the pain experience were not reflected in the pain-related psychological constructs, such as pain anxiety and pain catastrophizing. While girls are not more anxious and do not catastrophize more about their APSP experience than boys, they do report more unpleasantness from their pain experience.

The absence of gender differences in APSP intensity is not consistent with the adult literature. Female gender has been identified as a risk factor for the development of APSP.Citation47 The presence of gender differences in children and adolescents is more ambiguous in the pediatric literature. As discussed previously, clinical studies have shown that girls are more likely to report acute and chronic pain.Citation15 However, results from this study are consistent with experimental studies showing that pain responses of boys and girls are comparable.Citation48–Citation50

Overall, girls reported higher levels of functional disability compared with boys, but significant gender differences were not found in levels of functional disability when only children were included who reported APSP 2 weeks after discharge from hospital. These results suggest that girls with APSP are no more likely than boys with APSP to report high levels of functional disability. This is in contrast with other studies of children and adolescents with chronic pain which found that girls report higher levels of functional disability compared with boys.Citation39,Citation51 It is possible that gender differences in functional disability emerge over time after children’s pain has become chronic.

Significant gender differences in analgesic consumption were not found on the first day after surgery. These results are consistent with some findings in the adult literature. One review of the literature suggests that approximately 45% of studies failed to show a significant gender difference in opioid use, while 55% of studies found that males are more likely to consume a greater amount of opioid medication postoperatively. Citation52 The results are also consistent with a study of APSP which failed to show gender differences in the use of opioid analgesics among adolescents undergoing surgery.Citation5

Analgesic consumption on the day after surgery was significantly associated with pain unpleasantness, but not pain intensity 48–72 hours after surgery, such that children with a higher intake of analgesic reported less pain unpleasantness. These results suggest that analgesic consumption in these children is associated with the affective dimension of the pain experience more than the sensory dimension. In contrast, a study of children undergoing adenoidectomy found that analgesic consumption in the post anesthesia care unit was significantly associated with intensity of APSP.Citation53

Correlates of APSP and predictors of functional disability

Pain anxiety and pain catastrophizing were associated with pain intensity and unpleasantness, respectively, 48–72 hours after surgery. In contrast, pain anxiety measured 48–72 hours after surgery, but not pain catastrophizing, significantly predicted levels of functional disability 2 weeks after discharge from hospital. These results suggest that 48–72 hours after surgery, when pain is at its most intense, children are most anxious about the pain experience while they tend to amplify, ruminate, and feel powerless in the presence of the unpleasant quality of the pain experience. By the 2-week follow-up, after the children have returned home, their ability to perform their everyday activities appears to be limited by pain-related anxiety.

Consistent with a study of children who underwent spinal fusion,Citation20 the present findings show that prior surgical experience was not associated with higher APSP intensity. APSP is typically associated with central sensitization and other changes in nociceptive processing in the central nervous system.Citation54 These results suggest that individuals who have previously undergone surgery without developing CPSP are not more susceptible to subsequent pain experiences or to developing CPSP due to a subsequent surgery.

Prior surgical experience was associated with lower levels of anxiety and anxiety sensitivity 48–72 hours after surgery, raising the possibility that it is protective against psychological distress experienced in the acute post-surgical period. Children who have previously undergone surgery might have clearer expectations of the perioperative and recovery processes, resulting in lower anxiety relative to surgery-naïve children. However, it may also reflect a sampling bias, in that among patients who have had previous surgery, only those with low anxiety and anxiety sensitivity agreed to participate.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. First, no preoperative measures were collected, which would have allowed the examination of baseline levels of pain-related psychological constructs before the acute pain event. Second, results from this study cannot be generalized to minor surgical procedures because all participants in this sample underwent major surgery. Third, given that the response rate for this study was 55%, children with higher APSP or higher levels of postoperative anxiety or pain catastrophizing refused to participate. Fourth, the FDI in the present study was measured using a four-point Likert scale and omitted the original “2” (“some trouble”), making it difficult to compare levels of functional disability in this study with other studies of pediatric post-surgical pain.

In conclusion, the present results show that compared with boys, girls exhibit higher levels of acute postoperative anxiety and pain unpleasantness 48–72 hours, after surgery as well as higher levels of functional disability 2 weeks after discharge from hospital. Girls and boys reported similar levels of APSP intensity. In addition, pain anxiety is significantly associated with APSP intensity and functional disability, while pain catastrophizing is associated with APSP unpleasantness. These results highlight the importance of the role pain-related psychological factors can play in the experience of APSP in children and adolescents. Future research directions include examination of biological and psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between pain-related constructs and APSP, as well as the development of interventions to decrease the pain experience for children with elevated levels of pain anxiety and pain catastrophizing shortly after major surgery.

Acknowledgments

MGP is supported by a Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. MGP is the recipient of a Lillian Wright Maternal Child Health Scholarship from York University, and a trainee member of Pain in Child Health and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategic Training Fellow in Pain: Molecules to Community. JS is supported by a Ministry of Health and Long-term Care Career Scientist Award. JK is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canada Research Chair in Health Psychology at York University

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- McGrathPARuskinDACaring for children with chronic pain: ethical considerationsPaediatr Anaesth200717650550817498011

- KarlingMRenstromMLjungmanGAcute and postoperative pain in children: a Swedish nationwide surveyActa Paediatr200291666066612162598

- AlexMRRitchieJASchool-aged children’s interpretation of their experience with acute surgical painJ Pediatr Nurs1992731711801625173

- MatherLMackieJThe incidence of postoperative pain in childrenPain19831532712826134266

- LoganDERoseJBGender differences in post-operative pain and patient controlled analgesia use among adolescent surgical patientsPain2004109348148715157709

- PolkkiTPietilaAMVehvilainen-JulkunenKHospitalized children’s descriptions of their experiences with postsurgical pain relieving methodsInt J Nurs Stud2003401334412550148

- RomsingJWalther-LarsenSPostoperative pain in children: a survey of parents’ expectations and perceptions of their children’s experiencesPaediatr Anaesth1996632152188732613

- PalermoTMDrotarDPrediction of children’s postoperative pain: The role of presurgical expectations and anticipatory emotionsJ Pediatr Psychol19962156836988936897

- PalermoTMDrotarDDLambertSPsychosocial predictors of children’s postoperative painClin Nurs Res1998732752919830926

- GidronYMcGrathPJGooddayRThe physical and psychosocial predictors of adolescents’ recovery from oral surgeryJ Behav Med19951843853997500329

- Bennett-BransonSMCraigKDPostoperative pain in children: Developmental and family influences on spontaneous coping strategiesCan J Behav Sci1993253355383

- CrandallMLammersCSendersCBraunJVChildren’s tonsillectomy experiences: influencing factorsJ Child Health Care200913430832119833669

- GilliesMLSmithLNParry-JonesWLPostoperative pain assessment and management in adolescentsPain1999792/320721510068166

- TrippDAStanishWDReardonGCoadyCSullivanMJComparing postoperative pain experiences of the adolescent and adult athlete after anterior cruciate ligament surgeryJ Athl Train200338215415712937527

- PerquinCWHazebroek-KampschreurAHunfeldJPain in children and adolescents: a common experiencePain2000871515810863045

- HechlerTBlankenburgMDobeMKosfelderJHubnerBZernikowBEffectiveness of a multimodal inpatient treatment for pediatric chronic pain: a comparison between children and adolescentsEur J Pain201014197. e1e919362031

- HunfeldJAMPerquinCWDuivenvoordenHJChronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their familiesJ Pediatr Psychol200126314515311259516

- MartinALMcGrathPABrownSCKatzJChildren with chronic pain: impact of sex and age on long-term outcomesPain20071281/2131917055163

- FussSPagéMGKatzJPersistent pain in a community-based sample of children and adolescents: gender differences in psychological constructsPain Res Manag201116530331022059200

- KotzerAMFactors predicting postoperative pain in children and adolescents following spine fusionIssues Compr Pediatr Nurs20002328310211111499

- de MouraLAde OliveiraACPereira GdeAPereiraLVPostoperative pain in children: a gender approachRev Esc Enferm USP2011454833838 Portuguese21876881

- LamontagneLLHepworthJTSalisburyMHAnxiety and postoperative pain in children who undergo major orthopedic surgeryAppl Nurs Res200114311912411481590

- KainZNMayesLCCaldwell-AndrewsAAKarasDEMcClainBPreoperative anxiety, postoperative pain, and behavioral recovery in young children undergoing surgeryPediatrics2006118265165816882820

- ZvolenskyMJGoodieJLMcNeilDWSperryJASorrellJTAnxiety sensitivity in the prediction of pain-related fear and anxiety in a heterogeneous chronic pain populationBehav Res Ther200139668369611400712

- CrombezGEcclestonCBaeyensFEelenPWhen somatic information threatens, catastrophic thinking enhances attentional interferencePain1998752/31871989583754

- SullivanMJLBishopSRPivikJThe pain catastrophizing scale: development and validationPsychol Assess19957524532

- MartinALMcGrathPABrownSCKatzJAnxiety sensitivity, fear of pain and pain-related disability in children and adolescents with chronic painPain Res Manage2007124267272

- VervoortTGoubertLEcclestonCBijttebierPCrombezGCatastrophic thinking about pain is independently associated with pain severity, disability, and somatic complaints in school children and children with chronic painJ Pediatr Psychol200631767468316093515

- McCrackenLMZayfertCGrossRTThe Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale: development and validation of a scale to measure fear of painPain199250167731513605

- PagéMGFussSMartinALEscobarEMKatzJDevelopment and preliminary validation of the Child Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale in a community sampleJ Pediatr Psychol201035101071108220430838

- McCrackenLMDhingraLA short version of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS-20): preliminary development and validityPain Res Manag200271455016231066

- PagéMGCampbellFIsaacLStinsonJMartin-PichoraALKatzJReliability and validity of the Child Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (CPASS) in a clinical sample of children and adolescents with acute postsurgical painPain201115291958196521489692

- MarchJSParkerJDASullivanKStallingsPConnersCKThe Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability and validityJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19973645545659100431

- SilvermanWKFleisigWRabianBPetersonRAChildhood Anxiety Sensitivity ScaleJ Clin Child Psychol1991202162168

- ReissSMcNallyRJExpectancy model of fearReissSBootzinRRTheoretical Issues in Behavior TherapySan Diego, CAAcademic Press1985

- CrombezGBijttebierPEcclestonCThe child version of the Pain Catastrophization Scale (PCS-C): a preliminary validationPain200310463964612927636

- FaulstichMECareyMPRuggieroLEnyartPGreshamFAssessment of depression in childhood and adolescence: an evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC)Am J Psychiatry19861438102410273728717

- FendrichMWeissmanMMWarnerVScreening for depression disorder in children and adolescents: validating the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale for childrenAm J Epidemiol199013135385512301363

- WalkerLSGreeneJWThe functional disability inventory: measuring a neglected dimension of child health statusJ Pediatr Psychol199116139581826329

- Kashikar-ZuckSVaughtMHGoldschneiderKRGrahamTBMillerJCDepression, coping, and functional disability in juvenile fibromyalgia syndromeJ Pain20023541241914622745

- LynchAMKashikar-ZuckSGoldschneiderKRJonesBAPsychosocial risks for disability in children with chronic back painJ Pain20067424425116618468

- ReidGJMcGrathPJLangBAParent-child interactions among children with juvenile fibromyalgia, arthritis and healthy controlsPain20051131/220121015621381

- Von BaeyerCLNumerical rating scale for self-report of pain intensity in children and adolescents: recent progress and further questionsEur J Pain200913101005100719766028

- von BaeyerCLSpagrudLJMcCormickJCChooENevilleKConnellyMAThree new datasets supporting use of the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS-11) for children’s self-reports of pain intensityPain2009143322322719359097

- Canadian Pharmacists AssociationCompendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties: The Canadian Reference for Health ProfessionalsToronto, ONCanadian Pharmacists Association2012

- FaulFErdfelderEBuchnerALangA-GStatistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analysesBehav Res Methods20094141149116019897823

- KatzJSeltzerZTransition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain: risk factors and protective factorsExpert Rev Neurother20099572374419402781

- ChambersCTCraigKDBennettSMThe impact of maternal behavior on children’s pain experiences: an experimental analysisJ Pediatr Psychol200227329330111909936

- PiiraTTaplinJEGoodenoughBvon BaeyerCLCognitive-behavioural predictors of children’s tolerance of laboratory-induced pain: implications for clinical assessment and future directionsBehav Res Ther200240557158412038649

- TsaoJCGloverDABurschBIfekwunigweMZeltzerLKLaboratory pain reactivity and gender: relationship to school nurse visits and school absencesJ Dev Behav Pediatr200223421722412177567

- ClaarRLWalkerLSFunctional assessment of pediatric pain patients: psychometric properties of the functional disability inventoryPain20061211–2778416480823

- MiaskowskiCGearRWLevineJDSex related differences in analgesic responsesFillingrimRBProgress in Pain Research and Manageement17Seattle, WAInternational Association for the Study of Pain Press2000

- NikanneEKokkiHTuovinenKPostoperative pain after adenoidectomy in childrenBr J Anaesth199982688688910562784

- VoscopoulosCLemaMWhen does acute pain become chronic?Br J Anaesth2010105S1i69i8521148657