Abstract

Background

XaraColl®, a collagen-based intraoperative implant that delivers bupivacaine to the site of surgical trauma, is under development for postoperative analgesia. We compared the efficacy and safety of XaraColl for the prevention of postsurgical pain versus a slow postoperative perfusion of bupivacaine to the wound environment via the ON-Q PainBuster® Post-op Pain Relief System (ON-Q).

Methods

We randomized 27 women undergoing open gynecological surgery to receive either three XaraColl implants (each containing 50 mg bupivacaine hydrochloride) or ON-Q (900 mg bupivacaine hydrochloride perfused over 72 hours) in a 1:1 ratio. Following surgery, patients had access to intravenous morphine via a patient-controlled analgesia pump as rescue analgesia for the first 24 hours and to oral opioid medication thereafter. Total use of opioid analgesia was compared through 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours after surgery. Patients also evaluated overall pain control over the 96-hour period using a five-point numeric rating scale. Safety was assessed for 30 days after surgery.

Results

XaraColl was non-inferior to ON-Q in total use of opioid analgesia for the first 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours after surgery, with a statistical trend towards reduced opioid use in favor of XaraColl over 24, 48, and 72 hours (P = 0.067, 0.100, and 0.089, respectively). The time to first use of opioid analgesia was also significantly delayed in patients treated with XaraColl (P = 0.024). There was no significant difference between groups in patients’ evaluation of pain control or their satisfaction with the treatment in general. Both treatments were considered safe and well tolerated.

Conclusion

Despite using only 17% of the ON-Q dose, XaraColl is as effective as ON-Q in providing postoperative analgesia for 4 days after open gynecological surgery. These preliminary findings suggest that XaraColl offers great potential for the management of postoperative pain and warrants further definitive studies.

Introduction

Effective postoperative pain management is important for helping patients to have a smooth and successful recovery after their operation. For managing moderate to severe pain, intravenous morphine is often administered via a patient-controlled analgesia pump. However, the large doses required can often lead to fatigue, nausea, and vomiting, as well as the inability to mobilize because of drowsiness.Citation1,Citation2 Patients usually require patient-controlled analgesia for at least 24 hours before switching to oral analgesic medication.

Techniques that involve introduction of local anesthetic directly into the surgical wound, such as infiltration with bupivacaine, are thought to improve pain control and reduce the patient’s demand for opioid analgesia.Citation3,Citation4 Portable pain pumps, such as the ON-Q Pain Buster® Post-op Pain Relief System (ON-Q) (I-Flow Corporation, Lake Forest, CA; ), are designed to provide a constant flow of local anesthetic directly to a surgical wound postoperatively. However, such devices require specialized preparation, can create potential safety issues, and must be removed at a subsequent hospital visit.

Figure 1 ON-Q Pain Buster® Post-op Pain Relief System (I-Flow Corporation, Lake Forest, CA).

To overcome the problems associated with pain pumps, XaraColl® (Innocoll Technologies, Athlone, Ireland; ) is under development as an intraoperative implant for postoperative analgesia. The product uses a biodegradable and fully resorbable collagen-based matrix to deliver bupivacaine for local, sustained action at the site(s) of trauma while maintaining low systemic levels well below neurotoxicity and cardiotoxicity thresholds.

Materials and methods

We conducted a randomized, multicenter, pilot study in women following open gynecological surgery to compare the efficacy and safety of XaraColl versus constant bupivacaine perfusion over 72 hours via ON-Q as a positive control (NCT00749749). The study was performed at six centers in the United States in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines following approval by an institutional review board, either centrally (Western Institutional Review Board, Olympia, WA) or locally at the trial center.

Eligible patients included women at least 18 years of age who were generally healthy and scheduled to receive an elective total abdominal hysterectomy or other nonlaparoscopic gynecological procedure for reasons other than malignancy (such as adenocarcinoma, cervical cancer, or leiomyosarcoma) to be performed under general anesthesia. A laparotomy incision for a benign nonhysterectomy gynecological procedure (such as myomectomy or adnexal surgery) was acceptable if the surgical indication was not to treat pelvic pain. A concomitant abdominal urethropexy or incidental appendectomy was also allowed. Patients who required laparoscopic procedures, supraumbilical or Maylard incisions, or concomitant vaginal procedures, such as anterior and posterior colporrhaphy, were excluded. Patients who required any additional surgical procedures either related or unrelated to abdominal hysterectomy during the same hospitalization (except for the specific allowed procedures noted above) or required neuraxial opioid analgesics during the surgery were excluded. We also excluded patients who required the use of an adhesion barrier, those who were being treated for chronic painful conditions or other concomitant illness with agents that could affect the analgesic response (such as central alpha agents, neuroleptic agents, and other antipsychotic agents, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or systemic corticosteroids), or who were considered by the investigator to be unreliable or incapable of complying with the requirements of the protocol. Patients who were considered suitable and provided written informed consent then underwent additional screening procedures, including a physical examination and routine laboratory tests, up to 28 days before surgery.

On the day of surgery, patients underwent confirmatory safety assessments, and those who continued to meet all study entry criteria were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive one of the following treatments: three XaraColl implants each containing 50 mg bupivacaine hydrochloride (150 mg total dose) or 0.25% bupivacaine hydrochloride perfused via ON-Q at a rate of 5 mL (12.5 mg) per hour for 72 hours postoperatively (900 mg total dose).

An independent statistician created and maintained a computer-generated randomization schedule which was used by the contractor (Aptuit, Kansas City, MO) responsible for packaging and labeling the clinical supplies, to create study kits containing either the three XaraColl implants or the ON-Q device and drug components for the bupivacaine perfusion. Two-part labels were computer-generated, whereby one part was attached to the kit container and the other was a tear-off portion that contained the same information to be removed at the time of dispensing and attached to the patient’s case report form. The study was not blinded due to the different nature of the two treatments.

Surgery was conducted under general anesthesia. The use of epidural anesthesia or local anesthetic infiltrations was prohibited. For patients randomized to receive XaraColl, the first implant was divided and placed between areas in the vault near the vaginal stump, the second implant was divided and placed across the incision in the peritoneum, and the third implant was divided and placed between the sheath and skin around the incision. For the patients randomized to receive ON-Q, one 12.5 cm ON-Q system soaker catheter was placed in the deep subcutaneous space overlying the fascia prior to wound closure, and the system was set at a rate of 5 mL/hour (equivalent to 12.5 mg/hour bupivacaine hydrochloride) for 72 hours. Time 0 was defined as the time of implantation of the first XaraColl implant or the time that the ON-Q catheter was connected to the elastomeric pump.

For the first 24 hours after surgery, patients received intravenous morphine via a patient-controlled analgesia pump as rescue analgesia. After 24 hours through to discharge, patients received hydrocodone–acetaminophen combination tablets upon request for breakthrough pain (maximum dose could not exceed 40 mg of hydrocodone in 24 hours). If oral medication was considered insufficient, intramuscular or intravenous morphine could be administered. All postoperative opioid administration from time 0 through 96 hours was recorded and converted to an intravenous morphine equivalent using a published equianalgesic conversion table.Citation5

Patients were permitted to be discharged after 48 hours; however, the length of hospital stay was determined by the investigator and policies of the institution. If discharged prior to 72 hours, patients were issued a diary with their oral opioid rescue analgesia and instructed to record all use of opioid analgesia, use of any other concomitant medications, and any adverse events experienced. They were also instructed to return to the study site for safety evaluations at hour 72 (day 3) and hour 96 (day 4). Hospital staff removed the ON-Q system at hour 72 from all patients who received it. Patients were subsequently contacted by telephone on day 8 (±1 day) to inquire about the surgical wound, whether they had experienced any adverse events, and if they had used any concomitant medications since the day 4 evaluations. Hospital staff additionally telephoned patients on day 30 (+2 days) to inquire if they had experienced any adverse events since day 8 and also as to their general well-being.

Efficacy assessments

The efficacy of XaraColl was primarily compared with that of the ON-Q system by evaluating the total use of opioid analgesia through 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours after surgery. To compare the perceived level of pain control provided by the two treatments further, patients were asked to evaluate pain control at hour 96 on a five-point numeric rating scale where 0 = poor, 1 = fair, 2 = good, 3 = very good, and 4 = excellent. They were also asked to score their satisfaction with elements of the study treatment that were unrelated to pain control using a five-point numeric rating scale where 1 = very dissatisfied, 2 = dissatisfied, 3 = somewhat satisfied, 4 = satisfied, and 5 = very satisfied. Patients were finally asked if they had experienced any problems or difficulties with the study treatment and, if so, to describe them.

Safety assessments

We collected safety data, including physical findings, vital signs, and laboratory assessments at scheduled intervals and recorded all adverse events and serious adverse events throughout the study duration. The investigator designated each adverse event based on clinical severity as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe,” reported its resolution, and assessed whether the event was “definitely,” “probably,” “unlikely,” or “not” related to the study treatment.

Endpoints and statistical methods

The principal efficacy endpoints were total use of opioid analgesia through 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours following surgery. We conducted pairwise comparisons of each variable using analysis of variance models, with treatment as the effect. Based on these models, the upper one-sided 95% confidence interval for the difference in use of opioid rescue analgesia (XaraColl minus ON-Q) was calculated for each time duration and used to assess the non-inferiority of XaraColl to the ON-Q treatment, assuming an upper non-inferiority margin of 20 mg (as prospectively selected on the basis of clinical judgment).

The time to first use of opioid rescue analgesia was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and we compared treatment groups using a log-rank test. For the patients’ overall evaluation of pain control and their treatment satisfaction unrelated to pain control, scores were compared across treatments using a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test. For the question assessing any problems experienced with treatment, the dichotomous response results were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

All efficacy assessments were performed using the predefined intent-to-treat population, which consisted of all randomized patients who underwent surgery and received a study treatment. Efficacy variables were summarized descriptively to include mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, and counts and proportions for categorical variables. All statistical tests examining for differences between treatment groups (ie, tests of superiority) were two-sided; P values ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant and P values > 0.05 but ≤0.10 were considered indicative of a trend towards statistical significance.

Safety evaluations for both studies were based on all randomized patients, and included summary reports for the incidence and severity of adverse events, and their relationship to the treatment.

The planned enrolment was 26 patients. Using nQuery Advisor version 4.0 (Statistical Solutions, Saugus, MA), we calculated that at the 0.05 significance level with a one-sided t-test, an upper non-inferiority margin of 20 mg intravenous morphine equivalent, and a common standard deviation of 25 mg, 13 patients per group would provide 63% power for determining non-inferiority assuming that there was no difference between treatment groups. We considered this statistical power to be acceptable for an initial pilot study.

Results

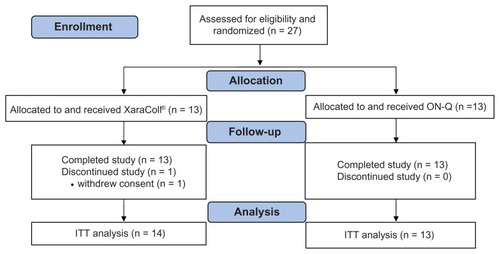

We enrolled 27 patients from September 2008 to December 2008; 14 were randomized to the XaraColl group and 13 to the ON-Q group. However, one patient randomized to receive XaraColl withdrew her consent after surgery and did not complete the study evaluations. The disposition of all enrolled patients is summarized in and the patient demographics, which were similar across treatment groups, are presented in .

Figure 3 CONSORT flow diagram.

Abbreviations: ITT, intent-to-treat; ON-Q, ON-Q Pain Buster® Post-op Pain Relief System.

Table 1 Patient demographics

Efficacy

The results for total use of opioid analgesia over each time period are summarized in as intravenous morphine equivalent. Through the first 24 hours, the mean difference was -20.2 mg (46.9 mg for XaraColl minus 67.0 mg for ON-Q), and the upper one-sided 95% confidence interval for this difference was -2.2 mg. Therefore, based on the predetermined non-inferiority margin of 20 mg, we considered XaraColl to be non-inferior to ON-Q. Furthermore, a statistical trend towards reduced opioid use was observed for the test of XaraColl superiority over ON-Q (P = 0.067).

Table 2 Total use of opioid rescue analgesia (mg intravenous morphine equivalent)

The mean total use of opioid rescue analgesia through 48, 72, and 96 hours was consistently lower in the XaraColl group (55.4, 62.0, and 67.9 mg, respectively) relative to the ON-Q group (74.9, 85.4, and 90.8 mg, respectively), with a statistical trend towards statistical significance through 48 and 72 hours (P = 0.100 and 0.089, respectively). Through 48, 72, and 96 hours, the mean difference for XaraColl minus ON-Q was −19.4 mg, −23.4 mg, and −22.9 mg respectively, and the upper one-sided 95% confidence interval for these differences was −0.01 mg, −0.8 mg, and 2.0 mg, respectively. Using the upper non-inferiority margin of 20 mg, Xaracoll was considered to be non-inferior to ON-Q for each time period.

From the Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to first use of opioid analgesia, 50% of patients took their first opioid medication at 0.78 and 0.57 hours after time 0 in the XaraColl and ON-Q groups, respectively. The probability of a patient having taken any opioid analgesia after one hour was 71% and 100% in the XaraColl and ON-Q groups, respectively. As determined by the log-rank test, the time to first use of opioid analgesia was significantly delayed in patients treated with XaraColl (P = 0.024).

The responses to the patient questions we asked at hour 96 are summarized in . From the five-point evaluation of pain control, a slightly higher proportion of patients treated with XaraColl (9/14 patients; 64.3%) rated their control as “excellent” compared with the ON-Q group (8/13 patients; 61.5%). However, this was mainly offset by a slightly higher proportion of patients in the ON-Q group (2/13 patients; 15.4%) who rated control as “very good” compared with the XaraColl group (1/14 patients; 7.1%). Overall, there was no significant difference in the patients’ rating of pain control (P = 0.847).

Table 3 Responses to patient questions

From the five-point evaluation of treatment satisfaction unrelated to pain control, a higher proportion of patients in the XaraColl group (9/14 patients; 64.3%) than in the ON-Q group (7/13 patients; 53.9%), reported being very satisfied with the study treatment. Two patients (15.4%) in the ON-Q group reported being “very dissatisfied” with the study treatment, whereas no patient in the XaraColl group was “very dissatisfied.” Furthermore, a higher proportion of patients in the ON-Q group (3/13 patients; 23.1%) than in the XaraColl group (1/14 patients; 7.1%) reported having problems or difficulties with the study treatment. However, these differences were not statistically significant for either patient satisfaction or the proportion of patients reporting a problem with their treatment (P = 0.176 and 0.593, respectively), although the study was not adequately powered to detect such differences.

Safety

Of the 27 patients enrolled, 16 (59.3%) experienced one or more adverse event during the study, as summarized in . The most common adverse events that occurred in ≥10% of patients in either treatment group were constipation, flatulence, nausea, pyrexia, headache, and rash. All adverse events were considered mild or moderate in severity. Three patients (23.1%) in the ON-Q group suffered postoperative nausea or vomiting, whereas only one patient (7.7%) who received XaraColl experienced postoperative nausea and vomiting. These relatively low incidences are encouraging, and consistent with interventions that are intended to reduce opioid consumption and associated opioid-related adverse events. Two patients in the XaraColl group reported adverse events that were considered by the investigator to be treatment-related (moderate flatulence, mild numbness at surgical incision). Neither event required additional treatment and both resolved without sequelae. There were no deaths or serious adverse events, and no patient discontinued due to an adverse event.

Table 4 All reported adverse events

Discussion

Postoperative pain has been identified as the most common concern of surgical patients,Citation6 and despite widely accepted treatment standards and guidelines, continues to be undermanaged.Citation7 Specifically, pain after abdominal hysterectomy can be quite severe and is generally considered multifactorial, involving incisional pain, visceral pain from deeper structures, and dynamic pain, such as that associated with straining, coughing, or mobilizing. However, visceral pain has been reported to dominate during the first 48 hours after hysterectomy.Citation8

Multimodal approaches to postoperative pain management have become the standard of care, but opioid analgesia continues to dominate most regimens.Citation9 Consequently, surgical patients remain at risk of opioid-related adverse events, such as respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, and sedation. In a retrospective multicenter study of 254 patients who received either intravenous fentanyl, morphine, or hydromorphone via patient-controlled analgesia, the incidence of commonly occurring opioid-related adverse events was found to be 20%, 46%, and 48%, respectively.Citation10 The most frequent opioid-related adverse event in all three groups was nausea/vomiting, which affected 18%, 33%, and 31% of patients, respectively.Citation10 Furthermore, opioid-related adverse events are often associated with longer hospital stays and increased costs of care. In one retrospective matched cohort study, the median length of stay was increased by 10.3% (P < 0.001) and the median total hospital costs were increased by 7.4% (P < 0.001) for those patients who experienced opioid-related adverse events.Citation11

However, undertreatment of pain is equally undesirable and can result in thromboembolic and pulmonary complications, additional time spent in hospital readmission, patient suffering, and development of chronic pain.Citation9 Therefore, pain management regimens that are effective and reduce opioid demand may help ameliorate adverse events related to both opioid use and undertreatment of pain.

Bupivacaine is a well described local anesthetic used postoperatively to block pain in surgical wounds as part of a multimodal treatment for postoperative pain. Ambulatory devices that provide a constant flow of local anesthetic to the subcutaneous space via an indwelling catheter, such as the ON-Q system approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, have been shown to reduce the need for opioid analgesia and the length of hospital stay.Citation12–Citation14 A meta-analysis of 44 randomized controlled trials involving 2141 patients found that continuous wound perfusion with local anesthetic significantly reduced opioid use and/or pain scores for all surgical subtypes analyzed (ie, cardiothoracic, general, gynecologic/urologic, and orthopedics).Citation15 However, these systems require specialized preparation, and patients fitted with ambulatory devices must return to the hospital for removal. Failure to follow the manufacturer’s directions may create safety issues, including the potential for delivery of the wrong dose of medication or a planned administration period that exceeds the expiry time allowed in the manufacturers’ specifications, which may contribute to the development of infection.Citation16,Citation17 External temperature may also have a clinically significant impact on device output, which could result in either inadequate analgesia or toxicity.Citation18

Our pilot study was designed to evaluate how the demand for opioid analgesia compared between patients who received constant subcutaneous perfusion of bupivacaine administered postoperatively via the ON-Q system (12.5 mg/hour over 72 hours for a total dose of 900 mg bupivacaine hydrochloride) and those treated intraoperatively with XaraColl. We decided to administer three implants placed at different depths in the pelvic cavity that would each deliver 50 mg of bupivacaine hydrochloride, giving a total dose of 150 mg. Despite delivering only 17% of the ON-Q dose, we found that the use of opioid analgesia was non-inferior to ON-Q within a predefined margin, and with a trend towards reduced demand.

By implanting at different depths within the surgical cavity, we believe XaraColl is able to treat both the visceral and incisional pain components simultaneously. In contrast, it is likely that little, if any, of the anesthetic perfused above the closed fascia can permeate to the deeper traumatized tissues. Indeed, as a drug delivery system, pain pumps are quite inefficient, with potential for anesthetic to ooze continuously from the wound where the catheter is placed. For example, one patient in our study who was randomized to ON-Q reported that the drainage from the catheter caused “gown, clothing, and bedding to be soaked.” Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that XaraColl is a more efficient delivery system than ON-Q, and thus could achieve comparable efficacy at a much lower dose.

There are several limitations to our study. Firstly, it was a pilot study enrolling only 27 patients, so had a relatively low statistical power compared with a confirmatory trial. Secondly, patients and investigators were not blinded to treatment group because of the fundamentally different treatment modalities that were compared. Thirdly, assessment of efficacy was based on patient use of opioid analgesia, which can be influenced by confounding factors such as patient attitudes and education.Citation19 However, we considered this to be the most appropriate endpoint because published studies specifically investigating the effectiveness of ON-Q have focused on the reduction of opioid consumption.Citation14,Citation20 Finally, from a safety perspective, the study is limited because we did not collect plasma samples to determine bupivacaine pharmacokinetics. Instead, we performed a separate study in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy to determine the pharmacokinetics of the XaraColl treatment only, which will be the subject of a companion publication.

Conclusion

On the basis of this pilot study, XaraColl appears to be at least as effective as constant bupivacaine perfusion for managing postsurgical pain over 4 days following open gynecological surgery. Of particular note is that XaraColl achieved similar efficacy using only 17% of the bupivacaine dose that was perfused over 3 days of treatment with ON-Q (ie, 150 mg versus 900 mg). Therefore, XaraColl appears to be a more efficient delivery system and, unlike ON-Q, can be implanted to target the deep visceral pain that may predominate. Both treatments in this study were considered safe and well tolerated. However, proportionately more patients reported usability problems with ON-Q that could be overcome with XaraColl. These preliminary findings suggest that XaraColl implanted intraoperatively may offer great potential for postsurgical analgesia, and warrants its further investigation in larger, double-blind trials.

Acknowledgment

We thank the following investigators and their study staff who enrolled patients in the studies: Keith Aqua (Visions Clinical Research), David Carpenter (Wilmax Clinical Research Inc), Richard Schroeder (MultiCare Health System), Steven Wininger (Precision Trials, LLC), and Joel Yarmush (New York Methodist Hospital).

Disclosure

This study was funded in whole by Innocoll Technologies Ltd, and coordinated by Premier Research Group Ltd (Philadelphia, PA) who recruited and monitored the sites, managed the clinical database, analyzed the data, and wrote the study report. HSM received research funding from Innocoll Technologies. MJ and SLC are paid consultants to Innocoll Technologies. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- StanleyGAppaduBMeadMRowbothamDJDose requirements, efficacy and side effects of morphine and pethidine delivered by patient-controlled analgesia after gynaecological surgeryBr J Anaesth1996764844868652316

- WoodhouseAMatherLEThe effect of duration of dose delivery with patient-controlled analgesia on the incidence of nausea and vomiting after hysterectomyBr J Clin Pharmacol19984557629489595

- CarpenterRLOptimizing postoperative pain managementAm Fam Physician1997568358449301576

- NgASwamiASmithGDavidsonACEmemboluJThe analgesic effects of intraperitoneal and incisional bupivacaine with epinephrine after total abdominal hysterectomyAnesth Analg20029515816212088961

- GordonDBStevensonKKGriffieJMuchkaSRappCFord-RobertsKOpioid equianalgesic calculationsJ Palliat Med1999220921815859817

- ApfelbaumJLChenCMehtaSSGanTJPostoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanagedAnesth Analg20039753454012873949

- WuCLRajaSNTreatment of acute postoperative painLancet20113772215222521704871

- LeungCCChanYMNgaiSWNgKFTsuiSLEffect of pre-incision skin infiltration on post-hysterectomy pain – a double-blind randomized controlled trialAnaesth Intensive Care20002851051611094665

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain ManagementPractice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an update report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain ManagementAnesthesiology20041001573158115166580

- HutchisonRWChonEHTuckerWFA comparison of a fentanyl, morphine, and hydromorphone patient-controlled intravenous delivery for acute postoperative analgesia: a multicenter study of opioid-induced adverse reactionsHosp Pharm200641659663

- OderdaGMSaidQEvansRSOpioid-related adverse drug events in surgical hospitalizations: impact on costs and length of stayAnn Pharmacother20074140040717341537

- GuptaAPerniolaAAxelssonKThornSECrafoordKRawalNPostoperative pain after abdominal hysterectomy: a double-blind comparison between placebo and local anesthetic infused intraperitoneallyAnesth Analg2004991173117915385371

- CheongWKSeow-ChoenFEuKWTangCLHeahSMRandomized clinical trial of local bupivacaine perfusion versus parenteral morphine infusion for pain relief after laparotomyBr J Surg20018835735911260098

- CottamDRFisherBAtkinsonJA randomized trial of bupivacaine pain pumps to eliminate the need for patient controlled analgesia pumps in primary laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypassObes Surg20071759560017658017

- LiuSSRichmanJMThirlbyRCWuCLEfficacy of continuous wound catheters delivering local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia: a quantitative and qualitative systemic review of randomized controlled trialsJ Am Coll Surg200620391493217116561

- BirrerKLAndersonRLLiu-DeRykeXPatelKRMeasures to improve safety of an elastomeric infusion system for pain managementAm J Health Syst Pharm2011681251125521690432

- SmetzerJCohenMRJenkinsRProcess for handling elastomeric pain relief balls (On-Q PainBuster and others) requires safety improvements Available from: http://www.ismp.org/Newsletters/acutecare/articles/20090716.aspAccessed July 31, 2012

- BurnettTBhallaTSawardekarATobiasJDPerformance of the On-Q pain infusion device during changes in environmental temperaturePaediatr Anaesth2011211231123321707833

- Wilder-SmithCHSchulerLPostoperative analgesia: pain by choice? The influence of patient attitudes and patient educationPain1992502572621454382

- DowlingRThielmeierKGhalyABarberDBoiceTDineAImproved pain control after cardiac surgery: results of a randomized double-blind clinical trialJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg20031261271127814665996