Abstract

Background

XaraColl, a collagen-based implant that delivers bupivacaine to sites of surgical trauma, has been shown to reduce postoperative pain and use of opioid analgesia in patients undergoing open surgery. We therefore designed and conducted a preliminary feasibility study to investigate its application and ease of use for laparoscopic surgery.

Methods

We implanted four XaraColl implants each containing 50 mg of bupivacaine hydrochloride (200 mg total dose) in ten men undergoing laparoscopic inguinal or umbilical hernioplasty. Postoperative pain intensity and use of opioid analgesia were recorded through 72 hours for comparison with previously reported data from efficacy studies performed in men undergoing open inguinal hernioplasty. Safety was assessed for 30 days.

Results

XaraColl was easily and safely implanted via a laparoscope. The summed pain intensity and total use of opioid analgesia through the first 24 hours were similar to the values observed in previously reported studies for XaraColl-treated patients after open surgery, but were lower through 48 and 72 hours.

Conclusion

XaraColl is suitable for use in laparoscopic surgery and may provide postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic patients who often experience considerable postoperative pain in the first 24–48 hours following hospital discharge. Randomized controlled trials specifically to evaluate its efficacy in this application are warranted.

Keywords:

Introduction

It is widely accepted that patients typically experience less postoperative pain with minimally invasive (laparoscopic) surgery, which in turn contributes to faster patient recovery, reduced hospital stay, and lower hospital costs compared to the corresponding open procedure.Citation1 These advantages mean that laparoscopic techniques are being developed and applied for an increasing variety of surgical procedures,Citation2,Citation3 enabling progressively more operations to be conducted on an ambulatory basis.Citation4 However, there remains little doubt that many patients undergoing ambulatory surgery still suffer significant postoperative pain,Citation5,Citation6 with 30% reporting moderate to severe pain after 24 hours.Citation7 Indeed, despite the need for smaller incisions compared to open procedures, the degree of visceral trauma is similar or even more extensive with laparoscopic access. Therefore, the management of early postoperative pain (ie, for at least the first 24–48 hours) is arguably just as important for patients who are promptly discharged after ambulatory surgery as for those who remain under hospital care for longer with potent analgesics readily at hand if needed.

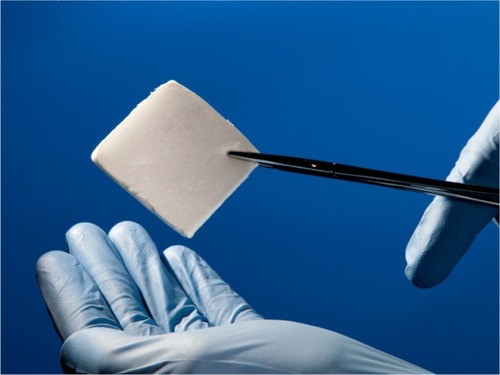

XaraColl (Innocoll Technologies, Athlone, Ireland) is a biodegradable and fully resorbable collagen matrix impregnated with the local anesthetic bupivacaine, which is under development for postoperative analgesia (). The product is implanted during surgery and releases bupivacaine for local, sustained action at the site(s) of surgical trauma, while maintaining low systemic levels well below the drug’s neurotoxicity and cardiotoxicity thresholds.Citation8 Recently reported multicenter randomized controlled trials have suggested that XaraColl is safe and effective for reducing postoperative pain and/or patient need of opioid analgesics for up to 72 hours following a laparotomy procedure such as open hernioplastyCitation9 or total abdominal hysterectomy.Citation10 The primary aim of this study was to determine whether it was possible to implant and appropriately position XaraColl laparoscopically. We are aware of no other studies where a purpose-designed, intraoperative anesthetic-delivery system has been evaluated for use in laparoscopic surgery.

Materials and methods

We conducted a feasibility study to investigate the use of XaraColl in ten men undergoing laparoscopic inguinal or umbilical hernia repair (NCT 01224145). The study was performed at Kirby Surgical Center (Houston, TX, USA) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines following approval by an institutional review board.

Eligible patients included men at least 18 years of age who were generally healthy and scheduled for either a unilateral laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty by the transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) or totally extraperitoneal (TEP) technique, or for a laparoscopic umbilical hernioplasty. We excluded patients who were scheduled for a bilateral inguinal hernia repair, had already undergone the repair at the same site of the scheduled surgery, or who had any concomitant illness that would significantly increase their surgical risk or make it difficult to complete the required assessments. Patients who were being treated with agents that could affect their analgesic response, such as central alpha agents, neuroleptic agents, and other antipsychotic agents, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, or systemic corticosteroids, were also excluded. Patients who were considered suitable and provided written informed consent then underwent additional screening procedures, including a physical examination and routine laboratory tests, up to 42 days before surgery.

On the day of surgery, patients underwent confirmatory safety assessments, and those who continued to meet all study entry criteria were allocated to receive the study drug. Surgery was conducted under general anesthesia, allowing use of short-acting agents such as propofol, midazolam, and fentanyl. The use of epidural anesthesia or local anesthetic infiltrations was prohibited. All patients received a total of four XaraColl implants, each containing 50 mg of bupivacaine hydrochloride (ie, 200 mg total dose), which were placed to achieve optimal coverage of the traumatized tissues and thereby target maximum postoperative analgesia. Time 0 was defined as the time of implantation of the first XaraColl implant.

For the laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, the implants were positioned over the abdominal wall repair (the repair mesh was then placed on top) and along the area that was dissected through the laparoscope to get to the repair site. For the laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair, the implants were placed under the mesh or ventral patch prior to the mesh or patch being secured around the site of the repair. For both procedures, one of the four implants, or a portion of the implant, was also placed under the subcutaneous tissue on top of the closed fascia. The implants were allowed to be cut as needed to best cover the sites of hernia repair and fascial closure. After surgery, the surgeon completed a questionnaire to record the method and ease of implantation.

Patients were observed and evaluated by hospital staff for a minimum of 4 hours after their surgery. Immediate postoperative pain was treated with intravenous morphine at incremental doses of 1–2 mg, as needed to achieve pain control. Once patients could tolerate oral medication, they were provided with immediate-release oral morphine tablets and instructed to take only if necessary for breakthrough pain. Patients could be discharged following the observation period, but were required to return to the study site 72 hours after surgery for their final assessments and follow-up visit. Study staff contacted patients by telephone approximately 1 week and 1 month after surgery to inquire about their surgical wound use of concomitant medications, any adverse events, and their general well-being.

Efficacy assessments

Patients assessed their pain intensity after aggravated movement (defined as cough) by using a visual analog scale with the left anchor (0 mm) labeled “No pain” and the right anchor (100 mm) labeled “Worst pain imaginable”. These pain assessments were scheduled at approximately 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours after time 0 (provided the patient was awake). The summed pain intensity (SPI) was defined and calculated as the trapezoidal area under the visual analog scale curve from 1 hour through to 24, 48, or 72 hours after time 0. Missing assessments were imputed according to the following prospective rules:

Any missing pain-intensity assessments before the first observed assessment were imputed with the patient’s worst observation (ie, their highest recorded visual analog scale score).

All other missing pain-intensity assessments were imputed using the patient’s last observation (ie, the observation prior to that missing).

In addition, the total use of opioid analgesia (TOpA) administered from time 0 through 72 hours was recorded and converted to intravenous morphine equivalent using a published conversion table.Citation11

Safety assessments

We collected safety data, including physical findings, vital signs, and laboratory assessments, at scheduled intervals and recorded all adverse events and serious adverse events throughout the study duration. An adverse event was defined as any clinically unfavorable and unintended sign (including abnormal laboratory findings), symptom, or disease, whether or not it was causally related to the treatment. A serious adverse event was defined as any adverse event that resulted in death, was life-threatening, required inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, resulted in permanent disability/incapacity or was an important medical event. We designated each adverse event based on clinical severity, defined as either “mild” (causes no limitation of usual activities), “moderate” (causes some limitation of usual activities), or “severe” (prevents or severely limits usual activities). We also assessed its expectedness and its relationship to treatment as either “definitely related,” “probably related,” “unlikely related,” or “not related.” Finally, the outcome of each adverse event at study completion was assessed and reported as either “recovered,” “resolved with sequelae,” “ongoing,” “death,” “other,” or “unknown.”

Results

We enrolled ten patients between March 2011 and May 2011, who all completed the study. Five patients had a laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair using the TAPP technique, and fve had a laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair. Patient age ranged from 31 to 63 years (mean 48 years). All patients were white or Caucasian, four of whom were of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity.

Feasibility of implantation

In all cases, the surgeon reported that the four XaraColl implants were easily implanted and properly positioned. No difficulties were encountered passing the implants through the laparoscope ports or with the implantation procedure itself. In most cases (nine out of ten patients), the implants were cut before implantation and positioned according to the type of hernia repair performed to cover all disrupted tissue. In eight out of ten patients, implants were affixed to the mesh either using a vicryl suture or by being threaded through the mesh tags.

Efficacy

The pain-intensity scores recorded at each assessment time are summarized in , and the calculated SPI and TOpA results are presented in . Since this was not a controlled study, we compared values of TOpA and SPI with previously reported pooled data from two studies of men undergoing open inguinal hernioplasty who also had the benefit of receiving XaraColl for postoperative analgesia.Citation9 After 24 hours, the mean TOpA for this laparoscopic study (19.3 mg) was very similar to the value from the pooled open hernioplasty studies (19.5 mg). The same was true for the mean SPI (805 mm·hour versus 883 mm·hour for the laparoscopic and open procedures, respectively). However, after 48 and 72 hours, XaraColl-treated patients in this laparoscopic study had taken less opioid analgesia and recorded lower pain intensity than the XaraColl-treated patients in the open studies. The mean TOpA was 26% and 38% lower in this laparoscopic study after 48 and 72 hours, respectively, and the corresponding SPI values were 17% and 25% lower.

Table 1 Pain intensity over time

Table 2 Results for SPI and TOpA through 24, 48, and 72 hours

Safety

A total of 18 adverse events were reported by eight of the ten patients (). The most common events were itching, nausea, headache, and hypoxemia, with each being reported by two patients. All other adverse events were reported by only one patient. All adverse events were mild to moderate in severity, and all were assigned as either “unlikely related” or “not related” to study medication, as determined by the investigator. Only one serious adverse event was reported (sleep apnea), where the patient remained in the hospital overnight for monitoring. This condition was previously undiagnosed, but was not considered related to the study medication and resolved with sequelae. No deaths or discontinuations due to adverse events were reported.

Table 3 All reported adverse events

Discussion

Hernia repair is the most common general surgical procedure performed in the United States, and it has recently been estimated that 42% of males will develop an inguinal hernia in their lifetime.Citation12 From studies comparing laparoscopic versus open repair of inguinal hernias, it is generally reported that laparoscopy offers the advantages of less postoperative pain and faster patient recovery, but at the expense of a more complex and longer operation,Citation1 and perhaps with increased risk of serious complications.Citation13–Citation15 However, other authors have argued that laparoscopic repair can be performed efficiently without major complications.Citation16 Laparoscopic repair of umbilicalCitation17–Citation20 and ventralCitation19 hernias have demonstrated similar benefits over open surgery.

Although laparoscopic procedures are widely considered less painful than the corresponding open procedure, well-controlled studies have shown this difference to be relatively modest. For example, in a large randomized trial that compared laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair involving more than 2000 patients at 14 centers, the difference in mean pain intensity at rest using a 150 mm visual analog scale was only 10.2 mm on the day of surgery and 6.2 mm after 2 weeks.Citation21 Similarly small differences were also reported during normal activities and patient perception of their worst pain.Citation21 In another prospective study comparing laparoscopic and open repair of ventral hernias, patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery had significantly lower pain scores at 72 hours postoperatively, but not at 24 or 48 hours.Citation19

Since early hospital discharge is a primary goal of laparoscopic surgery, the importance of controlling immediate postoperative pain has been recognizedCitation22 and multimodal analgesia recommended.Citation23,Citation24 Infiltration of abdominal wounds and/or instillation of the extraperitoneal space with bupivacaine have been investigated as possible methods for reducing postoperative pain following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in a number of randomized controlled trials. However, the results are contradictory, with some researchers reporting a significant benefitCitation22,Citation25 and others concluding the opposite.Citation26–Citation28 Similarly mixed results have been reported with use of intraperitoneal bupivacaine in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with someCitation29–Citation32 but by no means allCitation33–Citation35 studies demonstrating an analgesic effect. Another study concluded a detectable, albeit subtle and transient benefit.Citation36 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials acknowledged this high level of clinical heterogeneity, but still concluded there was evidence to support intraperitoneal administration of local anesthetics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.Citation37

The characteristics of pain following laparoscopy are thought to differ considerably from those after laparotomy,Citation33 with visceral pain predominating after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.Citation33,Citation38 Nevertheless, the reason for the inconsistent analgesic outcome with use of intraperitoneal bupivacaine following laparoscopic surgery is not obvious. One possible explanation is differences related to administration technique, since studies in patients undergoing laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair have shown that the timing of the instillation can influence its effectiveness.Citation31,Citation32 In another authoritative review of surgical wound infiltration, the importance of using controlled and meticulous techniques has been strongly emphasized.Citation39 Other studies have suggested that a surgical hemostat comprised of oxidized regenerated cellulose and soaked with bupivacaine can control the visceral pain when placed in the gallbladder bed after laparoscopic cholecystectomy.Citation38,Citation40

We have recently reported on the safety and efficacy of XaraColl, a bupivacaine-collagen implant, for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing open inguinal hernioplastyCitation9 and open gynecological surgery.Citation10 From the results obtained, we concluded that XaraColl implanted intraoperatively was able to target and control visceral pain more efficiently than continuous perfusion of the surgical wound with bupivacaine for 72 hours postoperatively.Citation10 Hence, XaraColl may be of particular benefit for reducing the postoperative pain normally experienced by patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery.

The purpose of this study was to first determine whether it is feasible and potentially effective to treat laparoscopic patients with XaraColl as a precursor to conducting any randomized controlled trial. We considered ten patients to be adequate for this initial feasibility investigation and decided to include two types of laparoscopic hernia repair, inguinal and umbilical. For the inguinal repair, we allowed both TAPP and TEP approaches, which are considered comparable.Citation41,Citation42 Surgeons reported that XaraColl was straightforward to implant in both the inguinal and umbilical repair procedures, thereby enabling the targeted release of bupivacaine at the major areas of tissue disruption and trauma.

Although our study was neither controlled nor powered to evaluate efficacy, we collected and analyzed pain scores and recorded patient use of opioid analgesia to compare with corresponding data obtained from earlier double-blind, randomized controlled trials that had demonstrated the efficacy of XaraColl for postoperative analgesia in men undergoing open hernioplasty. Our findings suggest that laparoscopic patients experience similar levels of postoperative pain to open surgical patients over the first 24 hours, but probably somewhat less pain thereafter through 48 and 72 hours. This finding is not unexpected based on the literatureCitation19 and the extent of deep-tissue trauma caused by laparoscopic hernia repair. Most importantly, however, it supports the view that immediate postoperative pain control is particularly important for ambulatory patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery who are scheduled for early hospital discharge.

When considered alongside the previous efficacy studies and the published literature in general, our study suggests that XaraColl may provide postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. However, randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusion

XaraColl, a bupivacaine-collagen implant under development for postoperative analgesia, can be safely implanted and appropriately positioned adjacent to the areas of tissue trauma in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. These patients tend to be discharged from the hospital on the day of surgery and so have particular need of postoperative pain control, especially in the first 24–48 hours. Randomized controlled trials are needed to further evaluate the efficacy of XaraColl for this application.

Acknowledgment

We thank the staff at Kirby Surgical Center who enrolled patients in this study.

Disclosure

This study was funded in whole by Innocoll Technologies Ltd, and coordinated by Premier Research Group Ltd, who recruited and monitored the sites. HSM received research funds from Innocoll Technologies. MK was involved in protocol development. SLC is a paid consultant for Innocoll Technologies. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RoummARPizziLGoldfardNICohnHMinimally invasive: minimally reimbursed? An examination of six laparoscopic surgical proceduresSurg Innov2005123261287 Erratum in Surg Innov. 2006;13(1):1616224649

- HarrellAGHenifordBTMinimally invasive abdominal surgery: lux et veritas past, present, and futureAm J Surg2005190223924316023438

- MartelGBousheyRPLaparoscopic colon surgery: past, present and futureSurg Clin North Am200686486789716905414

- CullenKAHallJGolosinskiyAAmbulatory surgery in the United States, 2006Natl Health Stat Report20091112819294964

- RawalNHylanderJNydahlPAOlofssonIGuptaASurvery of postoperative analgesia following ambulatory surgeryActa Anaesthesiol Scand1997418101710229311400

- BeauregardLPompAChoinièreMSeverity and impact of pain after day-surgeryCan J Anaesth19984543043119597202

- McGrathBElgendyHChungFKammingDCurtiBKingSThirty percent of patients have moderate to severe pain 24 hr after ambulatory surgery: a survey of 5,703 patientsCan J Anaesth200451988689115525613

- CusackSReginaldPHemsenLUmerahEThe pharmacokinetics and safety of an intraoperative bupivacaine-collagen implant (XaraColl®) for postoperative analgesia in women following total abdominal hysterectomyJ Pain Res2013

- CusackSJarosMKussMMinkowitzHWinklePHemsenLClinical evaluation of a bupivacaine-collagen implant (XaraColl®) for postoperative analgesia from two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot studiesJ Pain Res2012521722522792007

- CusackSJarosMKussMMinkowitzHHemsenLA randomized, multicenter, pilot study comparing the efficacy and safety of a bupivacaine-collagen implant (XaraColl®) with the ON-Q PainBuster® post-op relief system following open gynecological surgeryJ Pain Res201251922328829

- GordonDBStevensonKKGriffieJMuchkaSRappCFord-RobertsKOpioid equianalgesic calculationsJ Palliat Med19992220921815859817

- TreadwellJTiptonKOyesanmiOSunFSchoellesKSurgical options for inguinal hernia: comparative effectiveness reviewComparative Effectiveness Reviews201270

- JohanssonBHallerbäckBGliseHAnestenBSmedbergSRománJLaparoscopic mesh versus open preperitoneal mesh versus conventional technique for inguinal hernia repair: a randomized multicenter trial (SCUR Hernia Repair Study)Ann Surg1999230222523110450737

- McCormackKScottNWGoPMRossSGrantAMEU Hernia Trialists Collaboration. Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repairCochrane Database Syst Rev20031CD00178512535413

- GrantAMEU Hernia Trialists Collaboration. Laparoscopic versus open groin hernia repair: meta-analysis of randomised trials based on individual patient dataHernia20026121012090575

- WinslowERQuasebarthMBruntLMPerioperative outcomes and complications of open vs laparoscopic extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair in a mature surgical practiceSurg Endosc200418222122714625733

- GonzalezRMasonEDuncanTWilsonRRamshawBJLaparoscopic versus open umbilical hernia repairJSLS20037432332814626398

- LauHPatilNGUmbilical hernia in adultsSurg Endosc200317122016202014574545

- LomantoDIyerSGShabbirACheahWKLaparoscopic versus open ventral hernia mesh repair: a prospective studySurg Endosc20062071030103516703430

- WrightBEBeckermanJCohenMCummingJKRodriguezJLIs laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair with mesh a reasonable alternative to conventional repair?Am J Surg20021846505508 discussion 508–509012488148

- NeumayerLGiobbie-HurderAJonassonOOpen mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal herniaN Engl J Med200429:350181819182715107485

- Bar-DayanANatourMBar-ZakaiBZmoraOPreperitoneal bupivacaine attenuates pain following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairSurg Endosc20041871079108115156393

- ChauvinMState of the art of pain treatment following ambulatory surgeryEur J Anaesthesiol Suppl2003283612785455

- Elvir-LazoOLWhitePFPostoperative pain management after ambulatory surgery: role of multimodal analgesiaAnesthesiol Clin201228221722420488391

- HonSFPoonCMLeongHTTangYCPre-emptive infiltration of bupivacaine in laparoscopic total extraperitoneal hernioplasty: a randomized controlled trialHernia2009131535618704618

- SuvikapakornkulRValaivarangkulPNoiwanPPhansukphonTA randomized controlled trial of preperitoneal bupivacaine instillation for reducing pain following laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphySurg Innov2009162117112319468036

- SaffGNMarksRAKurodaMRozanJ PHertzRAnalgesic effect of bupivacaine on extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernia repairAnesth Analg19988723773819706934

- AbbasMHHamadeAChoudhryMNHamzaNNadeemRAmmoriBJInfiltration of wounds and extraperitoneal space with local anesthetic in patients undergoing laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal repair of unilateral inguinal hernias: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trialScand J Surg2010991182320501353

- EnesHSemirISefikHHusnijaMGoranIPostoperative pain in open vs laparoscopic cholecystectomy with and without local application of anaestheticMed Glas Ljek komore Zenicko-doboj kantona201182243248

- MraovićBJurisićTKogler-MajericVSusticAIntraperitoneal bupivacaine for analgesia after laparoscopic cholecystectomyActa Anaesthesiol Scand19974121931969062598

- PasqualucciAde AngelisVContardoRPreemptive analgesia: intraperitoneal local anesthetic in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyAnesthesiology199685111208694355

- BarczyńskiMKonturekAHermanRMSuperiority of preemptive analgesia with intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine before rather than after the creation of pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studySurg Endosc20062071088109316703434

- JorisJThiryEParisPWeertsJLamyMPain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: characteristics and effect of intraperitoneal bupivacaineAnesth Analg19958123793847618731

- JiranantaratVRushatamukayanuntWLert-akyamaneeNAnalgesic effect of intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine for postoperative laparoscopic cholecystectomyJ Med Assoc Thai20022085Suppl 3S897S90312452227

- ZmoraOStolik-DollbergOBar-ZakaiBIntraperitoneal bupivacaine does not attenuate pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomyJSLS20004430130411051189

- SzemJWHydoLBariePSA double-blinded evaluation of intraperitoneal bupivacaine vs saline for the reduction of postoperative pain and nausea after laparoscopic cholecystectomySurg Endosc199610144488711605

- KahokehrASammourTSoopMHillAGIntraperitoneal use of local anesthetic in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trialsJ Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci201017563765620393755

- VermaGRLyngdohTSKamanLBalaIPlacement of 0.5% bupivacaine-soaked Surgicel in the gallbladder bed is effective for pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomySurg Endosc200620101560156416897291

- ScottNBWound infiltration for surgeryAnaesthesia201065Suppl 1677520377548

- FerociFKröningKCScatizziMEffectiveness for pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy of 0.5% bupivacaine-soaked Tabotamp placed in the gallbladder bed: a prospective, randomized, clinical trialSurg Endosc200923102214222019184217

- CohenRVAlvarezGRollSTransabdominal or totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernia repair?Surg Laparosc Endosc1998842642689703597

- McCormackKWakeBLFraserCValeLPerezJGrantATransabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) versus totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a systematic reviewHernia20059210911415703862