Abstract

In patients, the perception of pain intensity may be influenced by the subjective representation of their disease. Although both multiple sclerosis (MS) and fibromyalgia (FM) possibly include chronic pain, they seem to elicit different disease representations because of the difference in their respective etiology, the former presenting evidence of underlying lesions as opposed to the latter. Thus, we investigated whether patients with FM differed from patients with MS with respect to their perception of “own” pain as well as others’ pain. In addition, the psychological concomitant factors associated with chronic pain were considered. Chronic pain patients with FM (n=13) or with MS (n=13) participated in this study. To assess specific pain-related features, they were contrasted with 12 other patients with MS but without chronic pain and 31 controls. A questionnaire describing imaginary painful situations showed that FM patients rated situations applied to themselves as less painful than did the controls. Additionally, pain intensity attributed to facial expressions was estimated as more intense in FM compared with the other groups of participants. There is good evidence that the mood and catastrophizing reactions expressed in FM differentially modulated the perception of pain according to whether it was their own pain or other’s pain.

Introduction

The perception of pain includes both an objective experience made of somatic sensory processes and a subjective experience consisting of affective–motivational features, as the consequence of actual or potential tissue damage (nociception). Thus, individuals base the estimation of their pain on objective sensory criteria, but also, they learn how to graduate their sensations according to personal values and beliefs. For instance, a study found that people who assessed their past and future health as poor reported more present pain.Citation1 Generally, the awareness of inner self is a complex and multifactorial variable, and self-assessment of one’s own pain is a challenging task. People tend to make biased evaluations of themselves and to use different criteria for judging themselves and others. For instance, normal volunteers reported a much more positive opinion of themselves than of others.Citation2,Citation3 In the pain domain, studies on empathy have shown that healthy participants scored pain with higher intensities when they experienced it than when they observed another individual in pain.Citation4 These results are consistent with the view that empathy is not a simple resonance of affect between the self and othersCitation5 but requires a more complex perspective. These results also suggest a large influence of subjective mechanisms in the attribution of pain intensity in normal volunteers. Accordingly, pain in self and in others have shown different patterns of activation of the sensory discriminative areas of the brainCitation6,Citation7 but shares similar neural activations in the anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula, both are known to participate in the (subjective) affective–motivational component of pain.Citation8,Citation9

Chronic diseases without evidence of lesions in the discriminative system but with psychogenic dysfunctions may be considered as interesting models to investigate how chronic pain influences the evaluation of “own” pain and others’ pain. Fibromyalgia (FM) may be considered as the prototype for these diseases, contributing to pain persistenceCitation10,Citation11 and showing abnormal activation in the nociceptive system, particularly, in the anterior cingulate cortex.Citation12,Citation13 By contrast, multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disease that is systematically associated with lesions of the central nervous system and that is frequently associated with pain symptoms. Intuitively, it seems evident that being in chronic pain or having a chronic disease may induce more empathy towards others’ pain. Additionally, it has been shown that chronic pain is accompanied by psychological symptoms, such as a propensity for catastrophizing, as well as by levels of anxiety and depression that are higher than normal.Citation14–Citation16 Therefore, this paper examined the impact of chronic pain on the perception of pain by paying particular attention to the psychological factors concomitant to the chronic pain.

The present study specifically addressed whether or not the presence of chronic pain has an effect on how people estimate painful experiences in themselves and in others. The study was initiated in patients with FM and was extended to a matched population of patients with MS and chronic pain. To discriminate the respective effects of chronic pain and the disease itself, two groups of MS patients were formed according to whether they suffered from pain (the MS-P group) or not (the MS-NP group). The FM group and both groups of MS patients were matched to a group of healthy volunteers. Since FM is often accompanied by behavioral and psychological symptoms, such as a propensity for catastrophizing,Citation17 as well as by levels of anxiety and depression that are higher than normal,Citation18,Citation11 we assumed that the levels of catastrophizing, anxiety, and depression would be higher in this group than in the MS-P group. In addition, anxiety, depression, and the “dramatization of pain” have been shown to increase the pain experience;Citation19 consequently, we speculated that patients with FM would have a greater tendency to overestimate pain than would the other groups. In other words, patients with FM would have more difficulty discriminating the different intensities of pain in various imaginary situations and displayed from facial expressions. Precisely, this difficulty should express itself in a higher score when they would have to imagine the intensity of pain felt in various imaginary situations, especially concerning their own pain; we further speculated that the FM group should assess painful facial expressions as more intense compared with the other group.

Methods

Participants

Thirty-eight patients and 31 healthy participants gave written informed consent, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The sociodemographic data of the participants are presented in .

Table 1 Participants’ characteristics

Thirteen patients with FM were referred by the Pain Unit of the Saint-Etienne Hospital, Saint-Priest-en-Jarez, France and met the diagnostic criteria for FM.Citation20 The mean duration of the disease was 5.07 years (standard deviation [SD]: ±3.01 years).

Twenty-five patients with MS were selected from the Department of Neurology at the Saint-Etienne University Hospital and the Germaine Revel Center at Saint-Maurice-sur-Dargoire, France. All of these patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria for MS as defined by the United States National Multiple Sclerosis Society in 1996.Citation21 Five patients had primary progressive MS, nine patients had relapsing remitting MS, and nine patients secondary progressive MS. They were split into the two groups MS-P and MS-NP according to whether they had pain or not in order to discriminate the respective effects of chronic pain and of the disease itself.

Pain falls into two categories: primary pain and secondary pain. For the present study, we included only MS patients with primary pain, in other words, with neuropathic pain, according to the criteria of O’Connor et al.Citation22 Patients, especially those in the MS group, with secondary pain, such as pain of psychological origin or pain associated with spasticity symptoms, were not included.

For both FM and MS patients, the exclusion criteria were as follows: other neurologic diseases, history of psychiatric illness, history of head trauma, history of alcohol or drug abuse, or present use of narcotics. Isolated mood disorder was not an exclusion criterion for these patients. All participants in the FM and MS groups had unchanged doses of medication.

Since cognitive impairments have been reported in both FMCitation23,Citation24 and MS,Citation25 patients were tested with the Mini Mental State Examination Test (MMSE)Citation26,Citation27 and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA)Citation28 ().

The exclusion criteria for healthy participants included any current psychiatric or neurological disorder. None of the control participants were taking psychoactive medication. The patient and control groups showed no significant differences with respect to age and educational level ().

Materials and procedure

Mood disorders and pain catastrophizing assessment

Depressive mood and anxiety were evaluated using the Self-assessment Questionnaire of Depression (QD2A)Citation29 for depressive symptomatology and the Anxiety Scale Questionnaire,Citation30 respectively. The cutoff thresholds were ≥7 for the QD2A and ≥5 for the Anxiety Scale Questionnaire. The French Canadian version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS-CF)Citation31 was used to assess pain catastrophizing.

Situational Pain Questionnaire

The procedure and tasks used in the present study, to assess the perception of pain in FM and MS patients compared to controls, were similar to those used in the Danziger et al study.Citation32 Firstly, to evaluate how FM and MS patients estimate their own pain sensitivity and the pain sensitivity of others, we used the French version of the Situational Pain Questionnaire (SPQ)-30 items version.Citation33 This includes 15 descriptions of painful events (eg, “The dentist drilled one of your teeth without anesthesia”) and 15 nonpainful events (eg, “Someone is bitten by a mosquito”). Participants completed two versions of the SPQ on the same sheet – one version interrogating their imagining of their own pain sensations in different situations (SPQself) and the second, the pain sensations they imagined in a normal other individual of the same gender and age (SPQother).

The items were evaluated using a numerical rating scale ranging from 1 (not noticeable) to 10 (worst possible pain) and yielded a discrimination score and a response bias score. The discrimination score P(A) indicates the ability of subjects to differentiate painful and painless situations. The P(A) can vary between 0 and 1: a score of 0 means no discrimination, a score of 0.5 is equivalent to a choice by chance, and a score of 1.0 represents perfect discrimination. The response bias (B) score indicates the extent to which the situations can be considered as painful. The less painful the situations are considered, the higher the B score. Both the P(A) and the B score were calculated as two scores, respectively P(A)self and P(A)other, and Bself and Bother.

Faces expressing pain

Additionally, the ability of patients to estimate the intensity of the pain of others from their facial expressions was assessed using the Sensitivity to Expressions of Pain Test (STEP Test).Citation34 This test consists of video clips showing facial expressions of patients undergoing different active and passive movements of their shoulders, some being painful. These clips were sampled and classified according to the intensity of pain reported using the Facial Action Coding System.Citation35 Facial Action Coding System is a method of describing facial movements developed by psychologists Ekman and Friesen in 1978.Citation35

Sixty 1-second sequences were randomly presented, with 20 depicting no pain, 20 depicting strong pain, and 20 depicting moderate pain. Three pretest sequences were used as examples before the 60 items were presented. The participants were asked to determine whether the sequence represented “no pain” (score 0), “moderate pain” (score 1), or “strong pain” (score 2). The scores were based on the nonparametric model of the signal detection theory, which provided two scores for discrimination P(A) and two scores for response bias (B): the difference between “no pain” and “moderate pain” expressions (P[A]NM and BNM); and the difference between “no pain” and “strong pain,” expressions (P[A]NS and BNS). P(A) and B values were calculated in similar manner as those for the SPQ. Note here that the response bias scores of the STEP Test were computed in such a manner that the higher the response bias, the higher the pain inferred. In contrast, the analyses conducted for the SPQ let to interpret the results as follows: the less painful the situations are considered, the higher the B score.

Data analyses

For each group, the mean scores were collected from the QD2A scale, the Anxiety Scale Questionnaire, and the Pain Catastrophinzing scale. Additionally, as mentioned, the P(A) and the B scores were calculated on data collected from the SPQ and STEP tests. Considering the small number of patients, the P(A) and the B scores were each rank-transformedCitation36 and treated to a separate analysis of variance (ANOVA) and of covariance (ANCOVA) with the group as the between-groups factor; the depression, anxiety, and catastrophizing variables were used as covariates. Post hoc comparisons were carried out using the Bonferroni adjustment.

Results

Mood and catastrophizing assessments

As described in , all patients with chronic pain (ie, the FM and MS-P groups) showed higher depression and anxiety scores than did the controls. The patients with FM had a higher catastrophizing score than did the controls, whereas the patients with MS-P did not differ from controls. As the likelihood of anxiety, depression, and catastrophizing was increased among the FM patients, these variables were used as covariates in the later analyses.

Table 2 Pain and mood assessments

Rating of imaginary situations (SPQ)

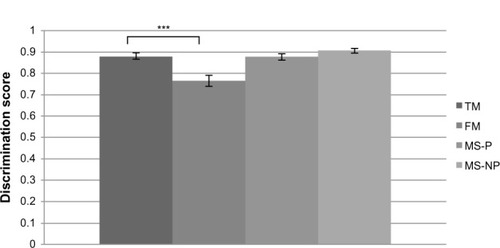

Firstly, the ANOVAs revealed a main effect of group (F[3,64]=6.41) (P=0.0007) for the version of the SPQ applied to the “self:” the FM patients showed a significantly lower P(A) than did the controls, P(A)self=0.76 (standard deviation [SD]: 0.09) versus 0.88 (SD: 0.07), respectively (P<0.0001). This pattern of results indicates that the FM patients were less able than others to differentiate between painful and nonpainful situations that applied to themselves (see ). Though ANOVA analyses revealed significant differences, no effect was revealed with the ANCOVA analyses. This means that the significant differences observed between the groups were due to the psychological factors assessed.

Figure 1 SPQ discrimination score for “self” pain.

Abbreviations: FM, fibromyalgia patients; MS-P, multiple sclerosis patients with pain; MS-NP, multiple sclerosis patients with no pain; SPQ, Situational Pain Questionnaire; TM, normal controls.

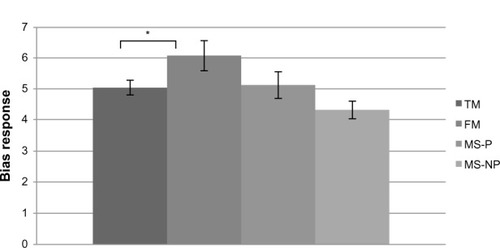

Similarly, ANOVAs revealed a main effect of group, F(3,64) =3.02 (P=0.03), when the B score was considered as the dependent variable. The FM patients showed significantly higher B scores than did the controls (Bself =6.07 [SD: 1.73] versus 5.04 [SD: 1.31], respectively) (P=0.03) or than the MS-P patients (Bself =5.13 [SD: 1.52]) (P=0.0002), indicating that they were less able than others to consider imaginary stimuli that applied to themselves as painful (see ). Once again, the ANCOVA analyses revealed no effect.

Figure 2 SPQ response bias for “self” pain.

Abbreviations: FM, fibromyalgia patients; MS-P, multiple sclerosis patients with pain; MS-NP, multiple sclerosis patients with no pain; SPQ, Situational Pain Questionnaire; TM, normal controls.

Finally, no significant difference was observed in the ratings of the SPQ applied to others.

Facial expressions of pain (STEP test)

Differences were mainly observed in the P[A]NM score (between faces expressing “moderate pain” and those expressing “no pain”) (F[3,64] =3.09) (P=0.03), and significant differences were found between the FM patients and the controls (P=0.01), between the MS-P patients and the controls (P=0.03), and with a trend toward significance between the MS-NP patients and the controls (P=0.06). This effect reflects that all patients, even MS-NP patients, were less able than controls to correctly distinguish subtle differences of intensity in facial expression (see ).

Table 3 Sensitivity to facial expressions of pain (STEP test)

The B score between “no pain” and “strong pain” on one hand and between “no pain” and “moderate pain” on the other hand showed a main effect of group (F[3,64] =3.54 [P=0.01] and F[3,64] =2.8 [P=0.04], respectively). Only the FM patients differed from the controls (“no pain” vs “strong pain”) (P=0.0009) () and from the other groups (“no pain” vs “moderate pain”) (P<0.01), in their manner of inferring increased pain intensities from facial expression.

When depression, anxiety, and catastrophizing were used as covariates, no significant difference was observed between the groups.

Discussion

FM patients showed significantly more mental distress, including depression and anxiety, than did the healthy controls. These findings replicate other studies showing a link between FM, anxiety and depression.Citation11,Citation37 Interestingly, these abnormalities were shared with the group of patients having MS and chronic pain. In contrast, the patients with FM were the only group of patients to overdramatize their pain in comparison with the control group. Therefore, within the field of this study, catastrophizing seems specific to FM but not to chronic pain. It has been reported that pain catastrophizing is significantly correlated with increased activity in the brain areas subserving anticipation, attention, and the emotional aspects of pain,Citation13 suggesting possible cognitive or fearful biases towards potentially painful events. Increased catastrophizing as well as the presence of anxiety and depression in FM should have led patients to assign a higher negative value to external painful stimuli.Citation38 Contrary to these predictions, the FM patients imagined pain situations applied to themselves as less painful than did the other groups. This downplay in the representation of pain intensity for external events applied to themselves (as described in the SPQ, for example, pain felt at the dentist) may suggest that they considered these painful situations to be less intense than their everyday pain. Conversely, when imaging pain in others, the performance of patients with FM did not differ from the control group, suggesting an intact ability for empathy. Similar abilities to properly assess pain in others have been previously reported in the extreme clinical situation of patients who never experience pain (congenital insensitivity to pain).Citation32 These results suggest that it is possible to adequately describe pain intensity in others through general knowledge and semantic cues, even in the absence of previous experience,Citation32 and a similar explanatory mechanism may apply to patients with FM. Such a semantic process does not apply to their own pain in patients with MS, suggesting a primary reference to their own emotional or sensorimotor maps. This discrepancy seen between the normal judgment of others’ pain based on semantic criteria and the downregulation of their own pain intensity processes seems relatively specific to FM patients, since it was not observed in MS-P patients.

Additionally, the patients with FM did not appear to benefit from emotional cues during the presentation of facial expressions since they overrated pain intensity as compared with controls. This result differs from findings in patients with congenital insensitivity to pain who had relatively normal performances – in spite of the absence of painful experiences, they were able to detect pain appropriately out of the emotional cues induced by facial expressions.Citation32 Since facial expressions are thought to involve the affective component of pain experience in the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula,Citation8,Citation24 a first hypothesis could be that patients with FM have increased sensitivity in this affective field, consistent with other experimental data.Citation39 An alternative hypothesis could be that patients with FM show excessive empathy when evaluating facial expressions of pain because they tend to project their own pain onto the stimuli. Accordingly, patients with MS, with or without pain, were less able than controls to distinguish the different intensities of pain on faces but showed very similar B scores. As compared with FM, they had very slight and restricted abnormalities in the area of empathy. This difference between patients with MS and those with FM may be explained first by the etiology of the disease that is clearly somatic for the former and with a potent psychosomatic component for the latter.

In conclusion, our results showed that the psychological factors concomitant to pain, especially in FM, are variables that minimized the judgment of pain intensity attributed to a situation of “own” pain, as evoked by semantic cues in the FM patients. This is a quite specific pattern of response, absent in patients with chronic pain from other origins. This is a pattern of response that does not apply to judgment of pain in others, suggesting, in FM patients, a normal empathic reaction to these semantic cues. In addition, the FM patients showed an increased empathic reaction based on emotional cues, as assessed with facial expressions, suggesting a generalized enhanced sensitivity to painful events. Again, this may be a relatively specific pattern of dysfunction since it is not observed in other patients with chronic pain.

The small number of participants may constitute one of the weak points of this study; however, even with weak statistical power, the results show significant differences, highlighting the importance of considering these results. Further studies seem necessary because of the small size of the group and to more precisely test the relative contributions of discriminative, emotional, and empathic reactions in patients with FM, to specify which of these components are impaired in FM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Nicolas Danziger (Paris) and Dr Kenneth Prkachin (Canada) who allowed us to use their experimental materials, the SPQ and the STEP. We additionally thank Dr Kenneth Prkachin for his valuable help in analyzing some of the results. This work received a 2011 research prize from the SFETD (French Society of Study and Treatment of Pain)/APICIL Foundation (Association of Interprofessional Foresight of Executives and Engineers of the Lyon region). This award was given beforehand to fund the study. Finally, we would like to thank Fannie Carrier-Emond for the corrections in English.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- IdlerELPerceptions of pain and perceptions of healthMotiv Emot1993173205224

- BaumeisterRFThe selfGilbertDTFiskeSTLindzeyGHandbook of Social PsychologyNew York, NYMcGraw-Hill1998680740

- ProninELinDYRossLThe bias blind spot: Perceptions of bias in self versus othersPers Soc Psychol Bull2002283369381

- JacksonPLBrunetEMeltzoffANDecetyJEmpathy examined through the neural mechanisms involved in imagining how I feel versus how you feel painNeuropsychologia200644575276116140345

- LammCBatsonCDDecetyJThe neural substrate of human empathy: effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisalJ Cogn Neurosci2007191425817214562

- OchsnerKNZakiJHanelinJYour pain or mine? Common and distinct neural systems supporting the perception of pain in self and otherSoc Cogn Affect Neurosci20083214416019015105

- SingerTSeymourBO’DohertyJKaubeHDolanRJFrithCDEmpathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of painScience200430356611157116214976305

- BotvinickMJhaAPBylsmaLMFabianSASolomonPEPrkachinKMViewing facial expressions of pain engages cortical areas involved in the direct experience of painNeuroimage200525131231915734365

- DecetyJJacksonPLThe functional architecture of human empathyBehav Cogn Neurosci Rev2004327110015537986

- CathébrasPTroubles Fonctionnels et Somatisation Comment Aborder les Symptômes Médicalement Inexpliqués [Functional Disorders and Somatization How to Deal with Medically Unexplained Symptoms]MassonParis2006 French

- LarocheFActualités sur la fibromyalgia [News on fibromyalgia]Rev Rhum Ed Fr200976529536 French

- DerbyshireSWJonesAKDevaniPCerebral responses to pain in patients with atypical facial pain measured by positron emission tomographyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry19945710116611727931375

- GracelyRHPetzkeFWolfJMClauwDJFunctional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgiaArthritis Rheum20024651333134312115241

- EcclestonCCrombezGAldrichSStannardCAttention and somatic awareness in chronic painPain1997721–22092159272805

- GrisartJMVan der LindenMConscious and automatic uses of memory in chronic pain patientsPain200194330531311731067

- GrisartJVan der LindenMMasquelierEControlled processes and automaticity in memory functioning in fibromyalgia patients: relation with emotional distress and hypervigilanceJ Clin Exp Neuropsychol2002248994100912650226

- GracelyRHGeisserMEGieseckeTPain catastrophizing and neural responses to pain among persons with fibromyalgiaBrain2004127Pt 483584314960499

- GormsenLRosenbergRBachFWJensenTSDepression, anxiety, health-related quality of life and pain in patients with chronic fibromyalgia and neuropathic painEur J Pain2010142127.e1127.e819473857

- FontaineRVanhaudenhuyseADemertziALaureysSFaymonvilleMEApport de la neuro-imagerie fonctionnelle à l’étude de la douleur [Contribution of functional neuroimaging to the study of pain]Rev Rhum Ed Fr

- WolfeFClauwDJFitzcharlesMAThe American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severityArthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201062560061020461783

- PolmanCHReingoldSCBanwellBDiagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteriaAnn Neurol201169229230221387374

- O’ConnorABSchwidSRHerrmannDNMarkmanJDDworkinRHPain associated with multiple sclerosis: systematic review and proposed classificationPain200813719611117928147

- ParkDCGlassJMMinearMCroffordLJCognition function in fibromyalgia patientsArthritis Rheum20014492125213311592377

- Verdejo-GarcíaALópez-TorrecillasFCalandreEPDelgado-RodríguezABecharaAExecutive function and decision-making in women with fibromyalgiaArch Clin Neuropsychol200924111312219395361

- ChiaravallotiNDDeLucaJCognitive impairment in multiple sclerosisLancet Neurol20087121139115119007738

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- KalafatMHugonot-DienerLPoitrenaudJStandardisation et étalonnage Français du “Mini Mental State” (MMS), version Greco [Standardization and calibration of the French “Mini Mental State” (MMS) GRECO version]Rev Neuropsychol2003132209236 French

- NasreddineZSPhillipsNABédirianVThe Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairmentJ Am Geriatr Soc200553469569915817019

- PichotPBoyetPPullCBReinWSimonMThibaultAA self evaluation inventory for depressive complaints, the QD2. II: Abridged version, QD2ARevue de Psychologie Appliquée1984344323340 French

- GoldbergDBridgesKDuncan-JonesPGraysonDDetecting anxiety and depression in general medical settingsBMJ198829766538978993140969

- FrenchDJNoëlMVigneauFFrenchJACyrCPEvansRTPCS-CF: A French-language, French-Canadian adaptation of the Pain Catastrophizing ScaleCan J Behav Sci2005373181192

- DanzigerNPrkachinKMWillerJCIs pain the price of empathy? The perception of others’ pain in patients with congenital insensitivity to painBrain2006129Pt 92494250716799175

- ClarkWCYangJCApplications of sensory detection theory to problems in laboratory and clinical painMelzackRPain Measurement and AssessmentNew York, NYRaven Press19831525

- PrkachinKMMassHMercerSREffects of exposure on perception of pain expressionPain200411181215327803

- EkmanPFriesenWVFacial Action Coding System. A Technique for the Measurement of Facial MovementPalo Alto, CAConsulting Psychologists Press1978

- ConoverWImanRLRank transformation as a bridge between parametric and non parametric statisticsAmerican Statistician198135124129

- ThiemeKTurkDCFlorHComorbid depression and anxiety in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to somatic and psychosocial variablesPsychosom Med200466683784415564347

- PetersMLVlaeyenJWvan DrunenCDo fibromyalgia patients display hypervigilance for innocuous somatosensory stimuli? Application of a body scanning reaction time paradigmPain200086328329210812258

- PiccinniABazzichiLMarazzitiDSubthreshold mood symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritisClin Exp Rheumatol2011296 Suppl 69S55S5922132737