Abstract

With a global prevalence of ~9%–12%, low back pain (LBP) is a serious public health issue, associated with high costs for treatment and lost productivity. Chronic LBP (cLBP) involves central sensitization, a neuropathic pain component, and may induce maladaptive coping strategies and depression. Treating cLBP is challenging, and current treatment options are not fully satisfactory. A new BioErodible MucoAdhesive (BEMA®) delivery system for buprenorphine has been developed to treat cLBP. The buccal buprenorphine (BBUP) film developed for this product (Belbuca™) allows for rapid delivery and titration over a greater range of doses than was previously available with transdermal buprenorphine systems. In clinical studies, BBUP was shown to effectively reduce pain associated with cLBP at 12 weeks with good tolerability. The most frequently reported side effects with the use of BBUP were nausea, constipation, and vomiting. There was no significant effect on the QT interval vs placebo. Chronic pain patients using other opioids can be successfully rotated to BBUP without risk of withdrawal symptoms or inadequate analgesia. The role of BBUP in managing cLBP remains to be determined, but it appears to be a promising new product in the analgesic arsenal in general.

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the top ten causes of years lived with disability (YLD) in every one of the 188 nations surveyed in the Global Burden of Disease Study of 2013 and also the leading cause of YLD in 45 of the 50 developed nations.Citation1,Citation2 The metric YLD is the number of incident cases multiplied by its average duration multiplied by a factor known as disability weight or, in some studies, it may be calculated by multiplying prevalent cases by the disability weight.Citation3 The rates of global mortality are not declining as rapidly as the rate of YLDs with the result that health care systems will be increasingly faced with the management of the nonfatal aspects of disease and injury worldwide.Citation4

LBP has been defined as pain that lasts at least 1 day in the posterior aspects of the body from the lower margin of the twelfth rib to the lower gluteal folds, which may or may not be accompanied by pain in one or both lower limbs.Citation3 It may be also defined as a pain in the lower back lasting at least 1 day that limits activity with or without pain referred to one or both lower limbs.Citation1 Global prevalence of LBP is estimated to be ~9%–12%.Citation1,Citation3,Citation5 The risk of LBP increases with ageCitation6 and is most prevalent among persons between the ages of 40 years and 80 years.Citation1 Most people (24%–80%) who experience one episode of activity-limiting LBP experience recurrent LBP at 1 year.Citation6

The costs of LBP are high, since they include medical expenditures, lost productivity, and expenses related to indemnity payments and litigation.Citation7–Citation9 In 1998, it was estimated that LBP cost the USCitation10 > $90 billion and in 2000, the UK estimated direct and indirect costs to be > 11 billion pounds.Citation11 Although it is impossible to state with authority exactly how much LBP costs society, it is clearly one of the costliest health care conditions.Citation6,Citation7

The etiology of LBP can be diverse and may include anatomical or structural problems (including bones, discs, ligaments, nerves, blood vessels, and muscles), osteoporosis, neoplasm, or infection.Citation6 Occupational risks for LBP include manual labor, bending, twisting, and being exposed to whole-body vibrations.Citation12 Other risk factors include low educational levels,Citation13 obesity,Citation14 stress, anxiety, depression,Citation15–Citation17 and job dissatisfaction,Citation18 although the latter four factors may be more directly associated with the transition from acute LBP to chronic LBP (cLBP).Citation16,Citation19

Most patients with nonspecific acute LBP have a favorable and unremarkable natural course in that the condition is typically brief and self-limited, with improvements occurring in ~4 weeks.Citation20 Patients with subacute LBP (lasting 4–12 weeks) usually improve as well but not as rapidly or completely. A subset of patients with acute LBP will develop cLBP, defined as LBP lasting ≥12 weeks; cLBP is difficult to treat and usually does not improve substantially over time.Citation20

Treating cLBP is challenging in part because chronic pain involves central sensitization and may include a neuropathic component. Patients with cLBP may also have comorbid conditions and psychosocial factors, such as maladaptive coping strategies and depression.Citation20

The first-line agents generally recommended for the control of cLBP are acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.Citation21 When such nonopioid pain relievers provide inadequate pain control, physicians may consider opioid analgesics, which carry with them risks for adverse events and abuse liability.Citation22,Citation23 Opioid analgesic agents are effective and may be used safely by certain patients under appropriate clinical supervision. Among these agents is a new buccal formulation of buprenorphine that may be particularly well suited for the treatment of cLBP. Buprenorphine is the only opioid agent that can be safely taken by elderly patients with no dosage adjustmentCitation24 and addresses both nociceptive and neuropathic pain components.Citation25 Buprenorphine has been clinically evaluated in the treatment of cLBPCitation26–Citation33 and is a well-known and widely used analgesic.

The purpose of this review is to evaluate a new formulation of buprenorphine with BioErodible MucoAdhesive (BEMA®; Endo Pharmaceuticals, Malvern, PA, USA) delivery technology for its potential role in the treatment of cLBP.

Methods

A literature search was conducted for keywords “buccal buprenorphine,” “Belbuca,” and “BEMA buprenorphine” in the PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Scopus databases, producing 152 results. Duplicates and articles not in English were removed (n=66), leaving 86 articles. Authors then reviewed the articles for relevance to the subject (buccal buprenorphine [BBUP] using BEMA technology for cLBP). Although no year constraints were employed in the search (to maximize results and not miss anything relevant), authors could also reject articles as outdated. A total of nine results remained ().

BEMA technology and buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a potent opioid that has been described as a partial mu-opioid receptor (MOR) agonist.Citation24 This terminology – a partial agonist – can be misleading, in that buprenorphine often acts like a full agonist in terms of clinical analgesic effect.Citation34 It offers durable analgesia in that it has high affinity for binding to MOR and slow dissociation from the MOR in the central nervous system.Citation35 Unlike other opioids, buprenorphine has been associated with antihyperalgesiaCitation36 and has a ceiling effect for both gastrointestinal side effects and respiratory depression.Citation24 Buprenorphine is associated with less abuse liability than many other opioid agents.Citation37 This may be due to the fact that it acts as an agonist at the opioid receptor-like 1 (NOP) receptor, which has been associated with attenuating the rewarding effect common with other opioids.Citation25,Citation38

The relatively poor oral bioavailability of buprenorphine (~15%Citation39) has led to the development of buprenorphine formulations as a transdermal system for pain control and a transmucosal product for opioid maintenance in dependent patients. The 7-day buprenorphine patch for chronic pain management is available in the doses of 5 µg/h, 7.5 µg/h, 10 µg/h, 15 µg/h, and 20 µg/h, with the two lower doses used primarily to initiate and titrate opioid-naïve patients.Citation39 Effective pain control has been demonstrated for buprenorphine patches at the doses of 10 µg/h, 15 µg/h, and 20 µg/h, giving buprenorphine transdermal systems a relatively narrow therapeutic dose range (10–20 µg/h).Citation40,Citation41 However, some patients may not achieve adequate analgesia with the doses of 20 µg/h.

In order to enhance and accelerate buprenorphine absorption, a buccal film delivery system was developed (Belbuca™); such a transmucosal film could increase titration flexibility and allow for a greater range of therapeutic doses. A novel and proprietary technology (BEMA) was developed to allow water-soluble polymeric films to adhere to the buccal mucosa and erode in a matter of minutes. Early testing found that this BBUP formulation had an absolute bioavailability of 46%–51% over a 16-fold range of doses.Citation42 Since steady-state conditions could be reached within ~3 days of dosing for transdermal products, BBUP offers therapeutic concentrations across a broad range of doses in a shorter time period than transdermal buprenorphine formulations.Citation42

The buccal mucosa is an intensively vascularized tissue with vessels that drain into the jugular vein, although drugs penetrate the epithelium to enter directly into systemic circulation rather than undergoing first-pass hepatic elimination in the gastrointestinal tract. A potential advantage for drug delivery via oral mucosa is accessibility, although saliva (dilution also known as the “washout” effect), oral pH fluctuations, drug taste, and relatively low absorptive surface area compared to the intestines may be viewed as potential drawbacks.Citation43 Two studies were conducted to evaluate the possible effects of ingesting liquids while receiving BBUP 90 µg in 57 healthy subjects.Citation44 BBUP was compared to sublingual buprenorphine 8 mg in a study in which they were administered to subjects without liquids, then just prior to hot water, cold water, tepid water, and low-pH and high-pH liquids. While high-pH liquids had no significant effect on systemic exposure to buprenorphine, low-pH liquids decreased the area under the curve (AUCinf) by ~37%. Water regardless of temperature decreased Cmax and the extent of buprenorphine absorption by 23%–27%. Levels of norbuprenorphine, the metabolite of buprenorphine, were similar in all groups. Based on AUCt and AUCinf, the relative bioavailability of BBUP compared to sublingual buprenorphine was 187% and 192%, respectively.Citation44

A number of buccal mucosa delivery systems for a variety of pharmaceuticals are currently in development or evaluation. The therapeutic areas for these novel products include pain, allergy, diabetes, and nicotine dependence.Citation45 BBUP with BEMA technology has been approved for the treatment of chronic pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long-term opioid therapy for which alternative treatment options are inadequate.Citation46

Pharmacokinetics

BBUP is available as buccal films in the doses of 75 µg, 150 µg, 300 µg, 450 µg, 600 µg, 750 µg, and 900 µg. It is metabolized by N-dealkylation, mainly via the cytochrome 3A4 enzyme, and glucuronidation and is eliminated in the feces (~70%) and urine (~30%). The Tmax is 2.5–3.0 hours with steady-state concentrations reached prior to the sixth dose, and it has a half-life of 27.6 hours.Citation47 The half-life for sublingual and transdermal buprenorphine formulations ranges from 20 hours to 73 hours.Citation48 The mean plasma elimination half-life of BBUP is 27.6±11.2 hours.Citation49 With the 7-day transdermal buprenorphine 20 µg/h patch, there is a gradual increase in the plasma concentration of buprenorphine over the first 2 days, plateauing at ~300 pg/mL at 48 hours. The mean plasma concentration at 24 hours is 143.5 pg/mL, with Cmax 318.6 pg/mL, and the mean AUC is 41,792.1 pg h/mL.Citation50 Sublingual buprenorphine, on the other hand, showed a plasma profile of 400 µg every 8 hours with large peak-to-trough differences over 24 hours. Note that buprenorphine absorption may be affected by the location of the site of application ().Citation50

Table 1 Pharmacokinetic parameters across various buprenorphine products indicated for pain control

Clinical efficacy

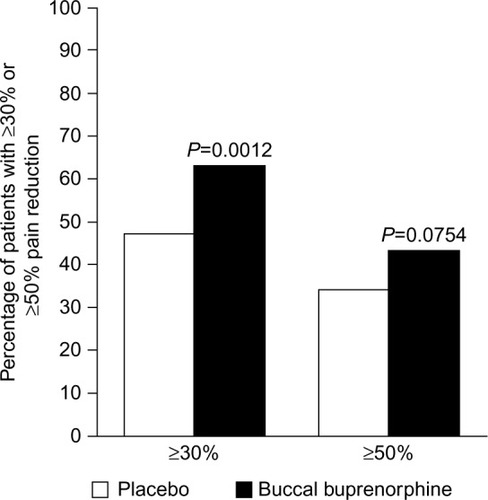

In a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 749 opioid-naïve patients with moderate to severe cLBP, patients were titrated to a dose of BBUP in the range of 150–450 µg every 12 hours that they could tolerate well and which provided adequate pain control for at least 14 days.Citation52 At that point, patients were randomized to continue BBUP (n=229) or be treated with placebo (n=232) and evaluated for the change in daily average pain intensity scores (numeric 11-point scale) from baseline to week 12 of treatment. The mean daily pain intensity score at baseline was 7.15±1.05. Pain was reduced markedly at drug titration with the mean daily pain intensity score of 2.81±1.07. Once patients were randomized, placebo patients had an increase in the pain score of 1.59±2.04 compared to BBUP where pain levels decreased by a mean of 0.94±1.85. The difference between BBUP and placebo patients at 12 weeks was significant (–0.67 difference, 95% CI, range –1.07 to –0.26, P=0.0012). Moreover, the proportion of patients who achieved a ≥30% reduction in pain was significantly larger in the BBUP group than in the placebo group (63% vs 47%, respectively, P=0.0012) (). The most common adverse events reported in the double-blind treatment phase of the study for BBUP were nausea, constipation, and vomiting (10%, 4%, and 4%, respectively), while the most common adverse events in the placebo group were nausea, upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and diarrhea (7%, 4%, 3%, and 3%, respectively).Citation52 There are several limitations of this study that must be noted. First, the double-blind phase of this study lasted 12 weeks, and longer term results cannot be inferred from these findings. Second, this study included a very specific patient population (opioid-naïve adults with cLBP for ≥6 months), and patients had to achieve adequate analgesia with BBUP prior to entering the study. Third, this study excluded patients with certain serious comorbid conditions, such as sleep apnea and unstable cardiac disease, and therefore, results may not be generalizable to the population of cLBP patients at large. Finally, this study used a placebo control rather than an active comparator control ().

Figure 2 Significantly more patients achieved ≥30% pain reduction in the BBUP (63%) vs placebo (47%) groups, P=0.0012.

Abbreviation: BBUP, buccal buprenorphine.

In a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind withdrawal study, opioid-experienced patients with moderate to severe cLBP were randomized to BBUP or placebo.Citation53 To enter the study, patients had to be previously taking 30–≤160 mg/d of morphine equivalents, and the doses were then tapered to ≤30 mg/d. At that point, patients underwent an open-label titration of BBUP (range 150–900 µg every 12 hours) that would provide adequate pain control and would be well tolerated. After 14 days, patients were randomized in a double-blind fashion to receive either BBUP or placebo, and the primary endpoint was the mean of the average daily pain intensity score change from baseline to week 12. Prior to titration, the mean pain score was 6.7±1.30. Following titration, the average baseline pain score had dropped to 2.8±1.02. Over the course of the study, pain scores increased to 1.92±1.87 for the placebo patients when compared with 0.88±1.79 for the BBUP patients (P<0.00001). Significantly more patients who achieved pain reductions by ≥30% and ≥50% were in the BBUP group compared to the placebo group (64% vs 31%, P<0.0001 and 40% vs 17%, P<0.0001, respectively).Citation53 The same limitations apply to this study: a specific and tightly defined patient population, placebo rather than active comparator as control, exclusion of patients with serious comorbidities, and adequate analgesia and tolerability of BBUP prior to entering the study. Again, this study had a double-blind phase of 12 weeks, and results cannot be generalized to longer time periods.

Safety

There have been concerns that buprenorphine, even at therapeutic doses, prolongs the QT interval on electrocardiography,Citation39 which has raised concern about prescribing buprenorphine to patients taking antiarrhythmic agents. Moreover, prolonged QT intervals could be problematic in any number of cardiac conditions, including, but not limited to, unstable atrial fibrillation and symptomatic bradycardia. A thorough QT study evaluated the effect of buprenorphine as a buccal soluble film on cardiac repolarization in 58 healthy subjects.Citation54 In this study, subjects received BBUP with naltrexone to mitigate opioid-associated effects that might potentially confound results. A separate group receiving only naltrexone was evaluated in the study. Subjects were randomized to one of the four groups receiving 3 mg of BBUP with naltrexone (50 mg of naltrexone was administered 12 hours prior to the first dose of buprenorphine); 50 mg naltrexone only on a placebo film; placebo (placebo on placebo film); and open-label moxifloxacin 400 mg. Except for the moxifloxacin group, all treatments were administered in a double-blind fashion. The study was designed as a four-period, crossover, single-dose evaluation. During each period, blood was drawn for pharmacokinetic evaluation, and 12-lead electrocardiography assessments were conducted. This study found that even supratherapeutic doses of BBUP administered with naltrexone did not cause any clinically significant QT interval prolongation. While there was a slight shortening of the changes from the baseline PR interval in all treatment periods, it appeared to be smaller in the BBUP and naltrexone groups than in the naltrexone alone and placebo groups. Naltrexone by itself did not appear to exert any relevant effect on the QT interval. Changes from the baseline QRS-interval were very small (≤1 ms at all time points).Citation54

In this same study, 67.2% (n=39) of patients reported at least one treatment-emergent adverse event.Citation54 This rate was highest among the buprenorphine plus naltrexone patients (53.7%) compared to patients who took naltrexone alone (30.8%), placebo patients (5.9%), or moxifloxacin patients (15.7%). In the BBUP and naltrexone groups, the most frequently reported adverse events were nausea (27.8%), dizziness (14.8%), vomiting (13.0%), and headache (7.5%); these events were relatively uncommon in the naltrexone alone, placebo, and moxifloxacin groups (<10% for each). Most of the adverse events were deemed to be mild, no serious adverse events were observed, and no subject withdrew from the study because of adverse events.Citation54

In a 12-week study of BBUP for cLBP (n=511), the most commonly reported adverse events during the double-blind phase of the study were nausea and vomiting (8% and 6%, respectively) for the BBUP patients and drug withdrawal syndrome and nausea (10% and 7%, respectively) for the placebo patients.Citation53

Opioid rotation to BBUP

Opioid rotation can be an important pharmacological strategy to allow patients with suboptimal results on one opioid to potentially achieve better results (improved analgesia, greater tolerability, or both) with another opioid agent.Citation55 Patients receiving a dose equivalent to 80–220 mg of oral morphine sulfate (n=35) were transitioned to BBUP at 50% of their full dose in a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, active-control two-period crossover study.Citation56 The primary endpoint of this study was a composite: either a maximum Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale score of ≥13 (moderate withdrawal) or the use of rescue medication to manage pain. All patients in the study had chronic pain and were confirmed as opioid dependent by naloxone challenge. It was found that these patients could be switched to BBUP without increased risk of withdrawal or exposure to inadequate analgesia.

Discussion

Chronic pain is a debilitating condition that decreases productivity, limits function, and reduces the quality of life. More than 100 million Americans suffer chronic painful conditions, with cLBP a leading cause, and many of these patients may be considered for opioid therapy.Citation57 Unrelieved chronic pain is epidemic in the US, and many cLBP and other chronic pain patients are not highly passionate advocates for better pain control. This is in part the nature of the disorder: with the passage of time, chronic pain causes individuals to withdraw from society, to retreat from activities, and to cope with life rather than engage. Opioids are effective pain relievers, and many patients benefit from their appropriate use. However, opioids carry with them a well-recognized abuse liability, and for this reason, many clinicians hesitate to prescribe them except for patients with the most severe forms of chronic noncancer pain. Indeed, there are respected experts who challenge the use of opioids in the setting of chronic nonmalignant pain altogether.Citation58,Citation59 Recent guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend limiting the use of opioids in patient populations such as patients with cLBP.Citation60

Pain experts are left to weigh the evidence in evaluating various pain control strategies and to make prescribing choices based on the needs and lifestyles of individual patients. The perfect analgesic agent does not yet exist. We have a pharmacological armamentarium of effective pain relief products, all of which carry some degree of risk. It is in this light that buprenorphine should be reconsidered. According to the World Health Organization, buprenorphine is considered as a strong opioid,Citation61 and it possesses a unique pharmacology and limited abuse liability.Citation24 It may be used without dose adjustment in elderly patients (a large subset of the chronic pain population) and those with renal dysfunction.Citation25 Buprenorphine administered transdermally is a convenient way of providing round-the-clock analgesia with good patient adherence.

The role of buprenorphine for pain control has been limited by concerns that it may be difficult to titrate adequately. Despite the apparent advantages of buprenorphine,Citation25 it is often considered as an “older drug” with limited utility. New indications for chronic pain, our knowledge of the drug and its unique pharmacology,Citation24 and the BBUP product make it worthy of a second look.

Transmucosal products are easy to administer and convenient for the clinical team. Patient acceptance of transmucosal products has not been well studied, although another transmucosal product (fentanyl) is on the market. The advantages of a convenient, rapid-onset opioid pain reliever with limited abuse liability makes the advent of this new BBUP particularly promising.

As with any opioid pain reliever, patients should be informed about the potential risks of opioid therapy, notably the risk of certain opioid-associated side effects and abuse liability. Opioid therapy should be closely supervised with patients and physicians setting goals for treatment that might include pain control, increased function, and specific personal goals such as being able to sit through a movie comfortably or being able to go out to dinner with the family. While pain assessments using validated metrics are important clinical tools, personal goals can have more relevance and be more motivational to the patient and his or her family than decreasing pain intensity numbers.

There are only a few studies in the literature addressing BBUP to date, and these studies have certain limitations. The authors could not find a BBUP study in the literature that compared BBUP with an active comparator. Furthermore, the studies described in our article evaluated BBUP over a 12-week time period (double-blind phase) in very refined patient populations who had achieved adequate analgesia and good tolerability with BBUP before entering the study. Thus, prudence is warranted when considering this new drug. Nevertheless, studies so far indicate that BBUP offers clinical efficacy, safety, tolerability, and versatility to help address cLBP. As such it must be considered as a promising and important new product for clinicians and their patients suffering from moderate to severe cLBP.

Conclusion

Buprenorphine is a potent and important opioid analgesic with a unique pharmacology. Until recently, buprenorphine’s availability to chronic pain patients was limited to transdermal patch systems in only three doses. BBUP offers a novel transmucosal technology that may enhance and accelerate buprenorphine absorption in the body. BBUP allows for greater dosing versatility (an important consideration for some cLBP patients). Buprenorphine is associated with a lower abuse liability than many other strong opioids, a ceiling effect for respiratory depression, and no requirement to adjust doses for the elderly or renally impaired patients. QT interval prolongation was not evident with BBUP even at supratherapeutic doses. Thus, BBUP may be an important new addition to help treat patients with moderate to severe pain associated with cLBP.

Disclosure

Dr. Pergolizzi is a speaker for ENDO, DEPOMED, Grünenthal, Purdue Pharma, and Mundipharma; he is a researcher for Purdue Pharma, Kaleo, and Collegium; and a consultant for Adapt, ENDO, Grünenthal, Purdue Pharma, and Insys Therapeutics. Dr. Pergolizzi received no funding related to the production of this manuscript. Dr. Raffa is a speaker, consultant, and/or basic science investigator for several pharmaceutical companies involved in analgesics research but receives no royalty (cash or otherwise) from the sale of any product. Drs. Fleischer, Taylor, and Zampogna are research fellows for NEMA Research Inc., a clinical research organization which provides clinical, regulatory, and product development services to a number of pharmaceutical companies.

References

- HoyDBainCWilliamsGA systematic review of the global prevalence of low back painArthritis Rheum20126462028203722231424

- GBD 2013 DALYs and HALE CollaboratorsMurrayCJBarberRMGlobal, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transitionLancet2015386100092145219126321261

- MarchLSmithEUHoyDGBurden of disability due to musculoskeletal (MSK) disordersBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol201428335336625481420

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 CollaboratorsGlobal, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2013Lancet2015386999574380026063472

- HoyDGSmithECrossMThe global burden of musculoskeletal conditions for 2010: an overview of methodsAnn Rheum Dis201473698298924550172

- HoyDBrooksPBlythFBuchbinderRThe epidemiology of low back painBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol201024676978121665125

- WalkerBMullerRGrantWLow back pain in Australian adults: the economic burdenAsia Pac J Public Health2003152798715038680

- BuchbinderRBlythFMMarchLMBrooksPWoolfADHoyDGPlacing the global burden of low back pain in contextBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol201327557558924315140

- KentPMKeatingJLThe epidemiology of low back pain in primary careChiropr Osteopat2005131316045795

- LuoXPietrobonRSunSXLiuGGHeyLEstimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United StatesSpine (Phila Pa 1976)2004291798614699281

- ManiadakisNGrayAThe economic burden of back pain in the UKPain Manag Nurs200084195103

- HoogendoornWEvan PoppelMNBongersPMKoesBWBouterLMSystematic review of psychosocial factors at work and private life as risk factors for back painSpine (Phila Pa 1976)200025162114212510954644

- DionneCEVon KorffMKoepsellTDDeyoRABarlowWECheckowayHFormal education and back pain: a reviewJ Epidemiol Community Health200155745546811413174

- WebbRBrammahTLuntMUrwinMAllisonTSymmonsDPrevalence and predictors of intense, chronic, and disabling neck and back pain in the UK general populationSpine (Phila Pa 1976)200328111195120212782992

- RubinDIEpidemiology and risk factors for spine painNeurol Clin200725235337117445733

- LintonSA review of psychological risk factors in back and neck painSpine20002591148115610788861

- CarrollLJCassidyJDCôtéPDepression as a risk factor for onset of an episode of troublesome neck and low back painPain20041071–213413914715399

- van TulderMKoesBBombardierCLow back painBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol200216576177512473272

- PincusTBurtonAKVogelSFieldAPA systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back painSpine (Phila Pa 1976)2002275E109E12011880847

- ChouRMcCarbergBManaging acute back pain patients to avoid the transition to chronic painPain Manag201111697924654586

- ChouRQaseemASnowVDiagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain SocietyAnn Intern Med2007147747849117909209

- ChouRFanciulloGJFinePGClinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer painJ Pain200910211313019187889

- ChouR2009 clinical guidelines from the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine on the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain: what are the key messages for clinical practice?Pol Arch Med Wewn20091197–846947719776687

- PergolizziJAloisiAMDahanACurrent knowledge of buprenorphine and its unique pharmacological profilePain Pract201010542845020492579

- DavisMPTwelve reasons for considering buprenorphine as a frontline analgesic in the management of painJ Support Oncol201210620921922809652

- ChaparroLEFurlanADDeshpandeAMailis-GagnonAAtlasSTurkDCOpioids compared to placebo or other treatments for chronic low-back painCochrane Database Syst Rev20138CD00495923983011

- GattiADauriMLeonardisFTransdermal buprenorphine in non-oncological moderate-to-severe chronic painClin Drug Investig201030suppl 23138

- GordonARashiqSMoulinDEBuprenorphine transdermal system for opioid therapy in patients with chronic low back painPain Res Manag201015316917820577660

- GordonACallaghanDSpinkDBuprenorphine transdermal system in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study, followed by an open-label extension phaseClin Ther201032584486020685494

- MillerKYarlasAWenWBuprenorphine transdermal system and quality of life in opioid-experienced patients with chronic low back painExpert Opin Pharmacother201314326927723374027

- MillerKYarlasAWenWThe impact of buprenorphine transdermal delivery system on activities of daily living among patients with chronic low back pain: an application of the international classification of functioning, disability and healthClin J Pain201430121015102224394747

- PetzkeFWelschPKlosePSchaefertRSommerCHauserWOpioide bei chronischem Kreuzschmerz. Systematische Übersicht und Metaanalyse der Wirksamkeit, Verträglichkeit und Sicherheit in randomisierten, placebokontrollierten Studien über mindestens 4 Wochen [Opioids in chronic low back pain. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, tolerability and safety in randomized placebo-controlled studies of at least 4 weeks duration]Schmerz20142916072 German

- PotaVBarbarisiMSansonePCombination therapy with transdermal buprenorphine and pregabalin for chronic low back painPain Manag201221233124654615

- RaffaRBDingZExamination of the preclinical antinociceptive efficacy of buprenorphine and its designation as full- or partial-agonistAcute Pain200793145152

- WolffRFReidKdi NisioMSystematic review of adverse events of buprenorphine patch versus fentanyl patch in patients with chronic moderate-to-severe painPain Manag20122435136224654721

- KoppertWIhmsenHKörberNDifferent profiles of buprenorphine-induced analgesia and antihyperalgesia in a human pain modelPain20051181–2152216154698

- LofwallMRWalshSLA review of buprenorphine diversion and misuse: the current evidence base and experiences from around the worldJ Addict Med20148531532625221984

- HuangPKehnerGBCowanALiu-ChenLYComparison of pharmacological activities of buprenorphine and norbuprenorphine: norbuprenorphine is a potent opioid agonistJ Pharmacol Exp Ther2001297268869511303059

- Drugs.com [webpage on the Internet]Butrans Skin Patch2016 Available from: http://www.drugs.com/pro/butrans-patch.htmlAccessed March 19, 2016

- SteinerDMuneraCHaleMRipaSLandauCEfficacy and safety of buprenorphine transdermal system (BTDS) for chronic moderate to severe low back pain: a randomized, double-blind studyJ Pain201112111163117321807566

- SteinerDJSitarSWenWEfficacy and safety of the seven-day buprenorphine transdermal system in opioid-naive patients with moderate to severe chronic low back pain: an enriched, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Pain Symptom Manage201142690391721945130

- BaiSAXiangQFinnAEvaluation of the pharmacokinetics of single-and multiple-dose buprenorphine buccal film in healthy volunteersClin Ther201638235836926804639

- PatherSIRathboneMJSenelSCurrent status and the future of buccal drug delivery systemsExpert Opin Drug Deliv20085553154218491980

- PriestleyTXiangSVasishtNCheruvuNFactors impacting the relative bioavailability of a new formulation of buprenorphineJ Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother2016174 suppl 1S888

- SilvaBMBorgesAFSilvaCCoelhoJFSimõesSMucoadhesive oral films: the potential for unmet needsInt J Pharm2015494153755126315122

- HanD webpage on the InternetBelbuca Now Available for Managing Severe, Chronic Pain2016 Available from: http://www.empr.com/news/belbuca-now-available-for-managing-severe-chronic-pain/article/478192/Accessed March 19, 2016

- Buprenorphine buccal film (Belbuca) for chronic painMed Lett Drugs Ther2016581492474827049508

- KhannaIKPillarisettiSBuprenorphine – an attractive opioid with under-utilized potential in treatment of chronic painJ Pain Res2015885987026672499

- Endo [webpage on the Internet]BELBUCA-Buprenorphine Hydrochloride FilmHighlights of Prescribing Information2015 Available from: http://www.endo.com/File%20Library/Products/Prescribing%20Information/BELBUCA_prescribing_information.htmlAccessed June 9, 2016

- PloskerGLBuprenorphine 5, 10 and 20 mug/h transdermal patch: a review of its use in the management of chronic non-malignant painDrugs201171182491250922141389

- Purdue Pharma [webpage on the Internet]BUTRANS-Buprenorphine Patch, Extended Release2014 Available from: http://app.purduepharma.com/xmlpublishing/pi.aspx?id=bAccessed June 9, 2016

- RauckRLPottsJXiangQTzanisEFinnAEfficacy and tolerability of buccal buprenorphine in opioid-naive patients with moderate to severe chronic low back painPostgrad Med20161281111

- GimbelJSpieringsELKatzNXiangQTazanisEFinnAEfficacy and tolerabilty of BEMA buprenorphine in opioid-experienced patients with modeate-to-severe chronic low back pain: primary results from a phase 3, enriched-enrollment, randomized withdrawal studyJ Pain2015164S85

- DarpoBZhouMBaiSAFerberGXiangQFinnADifferentiating the effect of an opioid agonist on cardiac repolarization from micro-receptor-mediated, indirect effects on the QT interval: a randomized, 3-way crossover study in healthy subjectsClin Ther201638231532626749217

- NalamachuSROpioid rotation in clinical practiceAdv Ther2012291084986323054690

- WebsterLGruenerDKirbyTXiangQTzanisEFinnAEvaluation of the tolerability of switching patients on chronic full mu-opioid agonist therapy to buccal buprenorphinePain Med Epub2522016

- TrangTAl-HasaniRSalveminiDSalterMWGutsteinHCahillCMPain and poppies: the good, the bad, and the ugly of opioid analgesicsJ Neurosci20153541138791388826468188

- ManchikantiLAtluriSHansenHOpioids in chronic noncancer pain: have we reached a boiling point yet?Pain Physician2014171E1E1024452651

- ManchikantiLBenyaminRDattaSVallejoRSmithHOpioids in chronic noncancer painExpert Rev Neurother201010577578920420496

- DowellDHaegerichTMChouRCDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain – United States, 2016MMWR Recomm Rep2016651149

- World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet]WHO’s Pain Ladder for Adults1988 Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/Accessed May 7, 2013