Abstract

Chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP), an often unanticipated result of necessary and even life-saving procedures, develops in 5–10% of patients one-year after major surgery. Substantial advances have been made in identifying patients at elevated risk of developing CPSP based on perioperative pain, opioid use, and negative affect, including depression, anxiety, pain catastrophizing, and posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms. The Transitional Pain Service (TPS) at Toronto General Hospital (TGH) is the first to comprehensively address the problem of CPSP at three stages: 1) preoperatively, 2) postoperatively in hospital, and 3) postoperatively in an outpatient setting for up to 6 months after surgery. Patients at high risk for CPSP are identified early and offered coordinated and comprehensive care by the multidisciplinary team consisting of pain physicians, advanced practice nurses, psychologists, and physiotherapists. Access to expert intervention through the Transitional Pain Service bypasses typically long wait times for surgical patients to be referred and seen in chronic pain clinics. This affords the opportunity to impact patients’ pain trajectories, preventing the transition from acute to chronic pain, and reducing suffering, disability, and health care costs. In this report, we describe the workings of the Transitional Pain Service at Toronto General Hospital, including the clinical algorithm used to identify patients, and clinical services offered to patients as they transition through the stages of surgical recovery. We describe the role of the psychological treatment, which draws on innovations in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy that allow for brief and effective behavioral interventions to be applied transdiagnostically and preventatively. Finally, we describe our vision for future growth.

Introduction

Chronic pain is the silent epidemic of our times.Citation1 The economic costs of chronic pain in the US are estimated to exceed the costs of heart disease, cancer and diabetes.Citation2 Chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) is a significant driver of this cost, with annual direct and indirect per patient estimates of US$41,000.Citation3 Given that the one-year incidence of moderate-to-severe CPSP is between 5% and 10%, and that world-wide, more than 230 million people undergo major surgery every year, the global annual cost of new cases of CPSP is in the hundreds of billions of dollars.Citation6 Equally concerning is the humanitarian cost of CPSP, which is all too frequently the unanticipated result of necessary and even lifesaving surgery. CPSP deprives the individual of vital energy and productivity and leads to many negative secondary, downstream effects.Citation7

The response to this costly tragedy has been unacceptably slow.Citation4 For more than 20 years, we have made progress in managing acute postsurgical pain through new insights and novel findings in pre-emptive/preventive analgesia.Citation4,Citation8,Citation9 In contrast, breakthroughs have not been made in minimizing the transition to CPSP. In order to accomplish this goal, we need a multidisciplinary preventive approach that involves intensive, perioperative psychological, medical, physical therapy, and pharmacological management interventions aimed at preventing and treating the factors that increase the risk of CPSP and associated disability.Citation4,Citation10,Citation11

In this paper, we briefly review the main risk factors for CPSP and then describe a novel multidisciplinary pain program, the Transitional Pain Service (TPS), which we have developed and implemented over the past year (since 2014). The TPS is designed specifically to identify patients at risk of CPSP, to intervene in a tailored and timely way medically, psychologically, and with complementary treatments to minimize the transition to chronicity, and to reduce reliance on opioid medications by focusing on treatment across the hospital-to-home trajectory. We anticipate the TPS will produce substantial savings, shorter hospital stays, earlier weaning from opioid analgesic medications, reduced emotional distress, improved quality of life, and reduced incidence and severity of CPSP and disability. Preliminary data already support some of these anticipated outcomes.Citation10,Citation11

Risk factors for CPSP

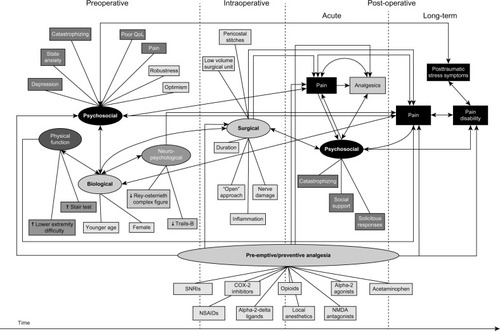

Over the past several years, substantial advances have been made in identifying risk factors for CPSPCitation4,Citation5,Citation12–Citation19 (). Our data and that from other published literature clearly show the following factors reliably predict CPSP across a range of surgical procedures: perioperative pain (the presence and intensity of preoperative pain, high intensity acute postoperative pain),Citation20–Citation25 perioperative opioid use,Citation20,Citation26 preoperative negative affective states including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-like symptoms,Citation27 depression,Citation28,Citation29 anxiety,Citation18,Citation28,Citation30–Citation32 and pain catastrophizing.Citation12,Citation17,Citation32,Citation33 The known psychological risk factors for CPSP (negative affect, catastrophizing) are also risk factors for intense, acute postoperative pain and high/excessive use of opioid analgesics in the acute postoperative setting.Citation34,Citation35 Inadequately controlled acute pain and excessive analgesic use have been repeatedly shown to delay recovery and hospital discharge following many surgeries.Citation36–Citation40 Moreover, high pain intensity,Citation41,Citation42 negative affect,Citation41,Citation43 and catastrophizingCitation41,Citation44 are all risk factors for opioid misuse/abuse in patients with chronic pain. Our own data show that 3% of previously opioid-naïve patients continue to use opioids 90 days after major elective surgery.Citation45 The TPS is designed to target and manage these known risks pre- and postsurgery in an effort to reduce pain, disability, and opioid misuse, while also benefitting the health care system by facilitating earlier discharge and reducing costs.

Figure 1 Schematic illustration of the processes involved in the development of chronic postsurgical pain and pain disability showing relationships among preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative risk/protective factors. Copyright © 2009 Katz and Seltzer. Adapted with permission from Katz J, Seltzer Z. Transition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain: risk factors and protective factors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(5): 723–744.Citation3

Overview of the TPS

The mission of the TPS is the treatment of patients who are at risk for transitioning from acute to CPSP. As such, it is the first service to comprehensively address the problem of CPSP after major surgery through multidisciplinary, coordinated care beginning preoperatively, extending postoperatively, and continuing into the posthospital discharge period once patients have returned home. The three primary goals of the TPS are to: 1) provide a novel, seamless approach to pre- and postoperative pain management for patients who are at increased risk for developing CPSP and pain disability, 2) manage opioid medication for medically complex patients post-discharge, and 3) improve patient coping and functioning in order to ensure as high a quality of life as possible after surgery.

Institutional setting

The TPS is situated at Toronto General Hospital (TGH), part of the University Health Network, in Toronto, ON, Canada. TGH is Canada’s leading surgical center, specializing in surgical oncology, cardiac surgery, vascular surgery, and multiorgan transplantation, with more than 6,000 surgeries performed annually. TPS patients have undergone a variety of surgical procedures () including procedures such as thoracotomy, mastectomy, and limb amputation, after which as many as one in two patients may develop CPSP.Citation4,Citation46

Table 1 Table of surgical procedures for patients enrolled in the Transitional Pain Service

TPS staff

Presently, the TPS comprises five anesthesiologists with advanced training in acute and/or chronic interventional pain management, two clinical psychologists and trainees, three acute pain nurse practitioners, two physical therapists with expertise in acupuncture, a palliative care specialist/family physician, an exercise physiologist, a patient-care coordinator, and an administrative assistant.

Patient flow during the pre- and intraoperative periods

Patients are identified as candidates for the TPS as early as the surgical preadmission visit, when a comprehensive medical assessment is performed, covering key areas such as preexisting conditions, current medications, and special considerations for anesthesia. At this time, approximately 12.5% of patients are identified with a “pain alert” due to chronic pain problems requiring daily opioid medication. This “pain alert” is attached to their chart for the duration of their surgical admission. These patients are assessed after surgery by the TPS, with particular attention to their needs as “acute-on-chronic” pain patients with high opioid requirements.

For a subset of highly complex patients, a multidisciplinary perioperative pain management plan is created prior to surgery; for example, a personalized pain management plan was created for a patient who was awaiting lung transplant in hospital, due to his complex clinical picture, including chronic degenerative lung disease, chronic back pain with high daily opioid use, a history of misuse of street drugs, as well as depression and anxiety. After assessment by the TPS, his opioid medication was reduced in preparation for transplant by adding opioid-sparing multimodal medication and his pain intensity decreased.

Patients who are not identified prior to surgery by screening in the preadmission clinic or by their surgical team can be referred to the TPS after surgery by the Acute Pain Service (APS) or by their surgical team. The APS refers patients to TPS if they have intense or prolonged postsurgical pain, high opioid use, notable emotional distress, or the need for ongoing expert pain management consultation and care (see for further details). TPS nurse practitioners begin in-hospital optimization of multimodal analgesia and enhanced teaching for the patient and their family. Patient education may include a review of the analgesics, guidance on better utilization of these analgesics and management of side effects, as well the importance of preventive analgesia in order to reduce pain upon movement and allow patients to participate more effectively in postoperative rehabilitation regimens. Next, one of the TPS pain physicians reviews the patient’s chart, assesses the patient (both in person and through a standardized self-report assessment battery), and develops a multidisciplinary pain plan tailored to the patient’s needs. This pain plan may include a referral to a TPS psychologist or physiotherapist, as appropriate, who then begins a personalized intervention while the patient is in hospital. Patients are followed by TPS with continued optimization of analgesic medication and involvement of the multidisciplinary team until hospital discharge. A key goal of this intensive team treatment is to reduce pain and distress as well as delayed discharge due to uncontrolled pain.

Table 2 Transitional Pain Service (TPS) referral criteria

Postoperative period

Once patients are medically fit for discharge, they are booked for follow-up appointments at the TPS outpatient clinic, also located at TGH. Patients receive a follow-up telephone call from the TPS team coordinator within 3 days of hospital discharge. In clinic, follow-up visits generally occur 2 to 3 weeks after discharge, but can take place within days for patients who need urgent care.

At the initial visit to the outpatient TPS clinic after surgery, patient progress is assessed and a detailed discussion is had with the patient (and the patient’s family, if present) regarding the pain treatment plan and the process of weaning from opioid medications. The patient is assessed for opioid addiction risk and an opioid agreement contract is signed prior to opioid prescribing. The clinical psychologist is involved with patients who are high-dose opioid users, who have a history of chronic pain or mental health problems, and/or those who report significant current distress and pain (assessed from a standardized set of psychological tools used at intake). Patients are also offered physiotherapy and/or acupuncture to help restore function and relieve pain. The primary care physicians and surgeons receive a summary of all clinic visits. Patients are assessed once every 2 to 3 weeks and their opioid medications and other analgesics are adjusted until they are at a safe level, their pain is under control, and their daily function approaches their baseline (presurgical) level. The TPS aims to transition patients back to their primary care physicians within 6 weeks to 6 months of hospital discharge (ie, after 3–6 visits).

The role of the psychological team within the TPS

Psychological intervention has a critical, widely established role in the effective multidisciplinary treatment of chronic pain.Citation47 In contrast, psychological intervention has rarely been central in the management of postsurgical pain, despite consistent findings that psychological factors such as pain catastrophizing, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic symptoms are predictive of CPSP outcomes (such as pain intensity, pain-related disability, and opioid use).Citation4,Citation48 There is a growing call for integration of psychological services from the earliest time point, rather than waiting for CPSP to be entrenched before such services are offered.Citation49,Citation50

Psychological assessment

The TPS is guided by our awareness of the psychological predictors of CPSP from our earliest contact with each patient. Upon referral to the service (prior to surgery or within days after surgery), patients complete validated self-report measures that assess psychological risk factors (such as pain catastrophizing, depression, and anxiety). In addition, patients undergo a brief assessment interview by a clinical psychologist. The goal of the assessment interview is twofold. First, for patients who are identified as distressed by self-report measures or by the APS, the interview gathers information on the nature of the distress (eg, depression, anxiety, PTSD, limited pain coping repertoire, stressful life circumstances) and identifies early targets for treatment. Secondly, the interview serves to screen for risk factors for opioid misuse. To this end, a brief history is taken of the patient’s presurgical functioning in relationships and education/employment, prior history of substance use and misuse, and mental health issues. Psychological risk factors for opioid misuse or difficult postsurgical recovery are communicated to the TPS team.

Psychological intervention

The goals of psychological intervention within the TPS are to 1) assist patients in the development of personalized pain management plans, 2) address distress and associated mental health issues that have the potential to amplify pain and increase opioid use, 3) support opioid weaning with behavioral pain management skills, and 4) reduce pain-related disability for patients with persistent pain. These key areas must be covered in a brief behavioral intervention that is acceptable to medical patients who are not seeking weekly psychotherapy or other such traditional psychological services.

Our primary modality of psychological intervention is a brief form of Acceptance and Commitment TherapyCitation51 (ACT) called the ACT Matrix.Citation52 ACT is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy that incorporates mindfulness, acceptance, and an emphasis on behavioral choices based on personal values.Citation53 ACT research on chronic pain has gained momentum over the past 15 yearsCitation54 and now ACT has been rated as having strong research support for the treatment of chronic pain, according to the American Psychological Association, Division 12.Citation55 In addition, a growing body of research supports the use of brief ACT workshops for medical patients, including patients with pain conditions such as migraine.Citation56 Indeed, medical patients who would not consider psychological treatment – even though they do have comorbid depression, for example – have reported that 1-day ACT workshops are acceptable and helpful to them.Citation56

We have adapted our brief ACT protocol into a presurgical workshop delivered in a group format, encompassing both behavioral intervention and pain psychoeducation. We can also provide the intervention to patients on a one-on-one basis, most commonly in a three-session protocol delivered after surgery. The psychological intervention covers many key areas, including identifying personal functioning goals, observing and describing pain and the thoughts and feelings that come with pain, identifying avoidance behaviors and analyzing when they exacerbate pain, distress, and dysfunction, and noticing the impact on pain of engaging in valued activities in a paced manner. A strength of this protocol is that it can be applied transdiagnostically to treat acute and/or chronic pain, depression, anxiety, PTSD, substance misuse, and personality disorders.Citation52 Our goal is to test our psychological intervention in a randomized controlled trial to better understand its impact, both short term and long term, on pain intensity, amount of opioid used, mood, and pain disability.

Moving forward: future developments for the TPS

Given the successful implementation of the TPS in the past year (since 2014), we have begun to expand the program in several ways.

We are now accepting referrals for outpatients with moderate to severe postsurgical pain who underwent surgery at other hospitals.

We have reached out to family physicians in the community to afford their patients an expedited assessment and intervention process if the patient is within 6 months of the surgical intervention.

We will be expanding the TPS to include patients undergoing orthopedic surgical procedures including total knee and total hip arthroplasties.

Based on our research in children and adolescents undergoing major surgery,Citation17,Citation19,Citation57 we have identified the transition from adolescence to young adulthood as another significant gap in transitional pain care and plan to develop a specialized arm of the TPS to manage these patients.

To enhance the provision of care within the TPS, we are designing physical fitness programs to prehabilitate and rehabilitate participants who are known to improve physical functioning and psychological resilience including yoga and mindfulness practices.Citation58

We have identified as a priority the need to implement a centralized pharmacy tracking system to monitor opioid prescriptions and prevent double doctoring.

To leverage e-health and mobile technology as a way of engaging TPS patients once they are discharged and as a way of improving the assessment and management of CPSP. Beyond complementing the existing TPS program, such technology may improve the accuracy and frequency of patient-reported pain outcomes, enable remote monitoring, provide exception-based alerts, and be a significant part of the equation for predictive analytics.

Conclusion

Taken together, the current TPS and planned expansions are designed to address the historical gaps in pain management for postsurgical patients. Our goal is to transform the management of pain in postsurgical patients by providing seamless care beginning preoperatively, continuing throughout the hospital stay and after patients return home post-hospital discharge. Finally, important next steps are to determine the efficacy of the TPS in preventing CPSP and to evaluate the extent to which the TPS reduces hospital stay, hospital readmission rates, and overall costs to the health care system.

Acknowledgments

Joel Katz is supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canada Research Chair in Health Psychology at York University. Hance Clarke is supported by a Merit Award from the Department of Anesthesia, University of Toronto and received funding from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, Medically Complex Patients Demonstration Project Program for a project entitled “The Transitional Pain Service Demonstration Project”.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WallPDJonesMDefeating Pain: The War Against a Silent EpidemicNew York, NYPlenum Press1991

- GaskinDJRichardPThe economic costs of pain in the United StatesJ Pain20121371572422607834

- ParsonsBSchaeferCMannREconomic and humanistic burden of post-trauma and post-surgical neuropathic pain among adults in the United StatesJ Pain Res2013645946923825931

- KatzJSeltzerZTransition from acute to chronic postsurgical pain: risk factors and protective factorsExpert Rev Neurother20099572374419402781

- KehletHJensenTSWoolfCJPersistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and preventionLancet200636795221618162516698416

- WeiserTGRegenbogenSEThompsonKDAn estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available dataLancet2008372963313914418582931

- VanDenKerkhofEGHopmanWMReitsmaMLChronic pain, healthcare utilization, and quality of life following gastrointestinal surgeryCan J Anaesth201259767068022547049

- ClarkeHBoninRPOrserBAEnglesakisMWijeysunderaDNKatzJThe prevention of chronic postsurgical pain using gabapentin and pregabalin: a combined systematic review and meta-analysisAnesth Analg2012115242844222415535

- KatzJClarkeHSeltzerZReview article: preventive analgesia: quo vadimus?Anesth Analg201111351242125321965352

- ClarkeHPoonMWeinribAKatznelsonRWentlandtKKatzJPreventive analgesia and novel strategies for the prevention of chronic post-surgical painDrugs201575433935125752774

- HuangAKatzJClarkeHEnsuring safe prescribing of controlled substances for pain following surgery by developing a transitional pain servicePain Manag2015529710525806904

- BurnsLCRitvoSEFergusonMKClarkeHSeltzerZKatzJPain catastrophizing as a risk factor for chronic pain after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic reviewJ Pain Research201515213225609995

- CohenLFouladiRTKatzJPreoperative coping strategies and distress predict postoperative pain and morphine consumption in women undergoing abdominal gynecologic surgeryJ Psychosom Res200558220120915820849

- HoltzmanSClarkeHAMcCluskeySATurcotteKGrantDKatzJAcute and chronic postsurgical pain after living liver donation: incidence and predictorsLiver Transpl201420111336134625045167

- KatzJAsmundsonGJMcRaeKHalketEEmotional numbing and pain intensity predict the development of pain disability up to one year after lateral thoracotomyEur J Pain200913887087819027333

- KatzJJacksonMKavanaghBPSandlerANAcute pain after thoracic surgery predicts long-term post-thoracotomy painClin J Pain199612150558722735

- PagéMGCampbellFIsaacLStinsonJKatzJParental risk factors for the development of pediatric acute and chronic postsurgical pain: a longitudinal studyJ Pain Res2013672774124109194

- PagéMGKatzJRomero EscobarMDistinguishing problematic from non-problematic post-surgical pain: a pain trajectory analysis following total knee arthroplastyPain32015156346046825599235

- PagéMGStinsonJCampbellFIsaacLKatzJIdentification of pain-related psychological risk factors for the development and maintenance of pediatric chronic postsurgical painJ Pain Res2013616718023503375

- HoofwijkDMFiddelersAAPetersMLPrevalence and predictive factors of chronic postsurgical pain and poor global recovery one year after outpatient surgeryClin J Pain Epub162015

- MiaskowskiCPaulSMCooperBIdentification of patient subgroups and risk factors for persistent arm/shoulder pain following breast cancer surgeryEur J Oncol Nurs201418324225324485012

- BruceJThorntonAJPowellRPsychological, surgical, and socio-demographic predictors of pain outcomes after breast cancer surgery: a population-based cohort studyPain2014155223224324099954

- Masselin-DuboisAAttalNFletcherDAre psychological predictors of chronic postsurgical pain dependent on the surgical model? A comparison of total knee arthroplasty and breast surgery for cancerJ Pain201314885486423685186

- HanleyMAJensenMPSmithDGEhdeDMEdwardsWTRobinsonLRPreamputation pain and acute pain predict chronic pain after lower extremity amputationJ Pain20078210210916949876

- BrandsborgBNikolajsenLHansenCTKehletHJensenTSRisk factors for chronic pain after hysterectomy: a nationwide questionnaire and database studyAnesthesiology200710651003101217457133

- VanDenKerkhofEGHopmanWMGoldsteinDHImpact of perioperative pain intensity, pain qualities, and opioid use on chronic pain after surgery: a prospective cohort studyReg Anesth Pain Med2012371192722157741

- KleimanVClarkeHKatzJSensitivity to pain traumatization: a higher-order factor underlying pain-related anxiety, pain catastrophizing and anxiety sensitivity among patients scheduled for major surgeryPain Res Manag201116316917721766066

- AttalNMasselin-DuboisAMartinezVDoes cognitive functioning predict chronic pain? Results from a prospective surgical cohortBrain2014137Pt 390491724441173

- ArcherKRSeebachCLMathisSLRileyLH3rdWegenerSTEarly postoperative fear of movement predicts pain, disability, and physical health six months after spinal surgery for degenerative conditionsSpine J201414575976724211099

- BelferISchreiberKLShafferJRPersistent postmastectomy pain in breast cancer survivors: analysis of clinical, demographic, and psychosocial factorsJ Pain201314101185119523890847

- KatzJPoleshuckELAndrusCHRisk factors for acute pain and its persistence following breast cancer surgeryPain20051191–3162516298063

- TheunissenMPetersMLBruceJGramkeHFMarcusMAPreoperative anxiety and catastrophizing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with chronic postsurgical painClin J Pain201228981984122760489

- KhanRSAhmedKBlakewayECatastrophizing: a predictive factor for postoperative painAm J Surg2011201112213120832052

- IpHYAbrishamiAPengPWWongJChungFPredictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic reviewAnesthesiology2009111365767719672167

- KatzJBuisTCohenLLocked out and still knocking: predictors of excessive demands for postoperative intravenous patient-controlled analgesiaCan J Anaesth2008552889918245068

- BarattaJLSchwenkESViscusiERClinical consequences of inadequate pain relief: barriers to optimal pain managementPlast Reconstr Surg20141344 Suppl 215S21S25254999

- GurusamyKSVaughanJToonCDDavidsonBRPharmacological interventions for prevention or treatment of postoperative pain in people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomyCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD00826124683057

- JonesNLEdmondsLGhoshSKleinAAA review of enhanced recovery for thoracic anaesthesia and surgeryAnaesthesia201368217918923121400

- JoshiGPOgunnaikeBOConsequences of inadequate postoperative pain relief and chronic persistent postoperative painAnesthesiol Clin North America2005231213615763409

- RobinsonKPWagstaffKJSangheraSKerryRMPostoperative pain following primary lower limb arthroplasty and enhanced recovery pathwayAnn R Coll Surg Engl201496430230624780024

- MorascoBJTurkDCDonovanDMDobschaSKRisk for prescription opioid misuse among patients with a history of substance use disorderDrug Alcohol Depend20131271–319319922818513

- JamisonRNLinkCLMarceauLDDo pain patients at high risk for substance misuse experience more pain? A longitudinal outcomes studyPain Med20091061084109419671087

- GrattanASullivanMDSaundersKWCampbellCIVon KorffMRDepression and prescription opioid misuse among chronic opioid therapy recipients with no history of substance abuseAnn Fam Med201210430431122778118

- MartelMOWasanADJamisonRNEdwardsRRCatastrophic thinking and increased risk for prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic painDrug Alcohol Depend20131321–233534123618767

- ClarkeHSonejiNKoDTYunLWijeysunderaDNRates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort studyBr Med J2014348g125124519537

- ShiptonEAThe transition of acute postoperative pain to chronic pain: Part 1 – Risk factors for the development of postoperative acute persistent painTrends Anaesth Crit Care2014426770

- FlorHFydrichTTurkDCEfficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic reviewPain19924922212301535122

- ShiptonEAThe transition of acute postoperative pain to chronic pain: Part 1 – Risk factors for the development of postoperative acute persistent painTrends Anaesth Crit Care2014426770

- ShiptonEAThe transition of acute postoperative pain to chronic pain: Part 2 – Limiting the transitionTrends Anaesth Crit Care201442–37175

- WicksellRKOlssonGLPredicting and preventing chronic postsurgical pain and disabilityAnesthesiology201011361260126120966742

- HayesSCStrosahlKDWilsonKGAcceptance and Commitment Therapy: The process and Practice of Mindful ChangeSecond EditionNew York, NYGuilford Press2011

- PolkKSchoendorffBACT Matrix: A New Approach to Building Psychological Flexibility across Settings and PopulationsOakland, CANew Harbinger Publications, Inc.2014

- HayesSCVillatteMLevinMHildebrandtMOpen, aware, and active: contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapiesAnnu Rev Clin Psychol2011714116821219193

- ScottWMcCrackenLMPsychological flexibility, acceptance and commitment therapy, and chronic painCurr Opin Psychol201529196

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy EST Status for Chronic or Persistent Pain: Strong Research Support Society of Clinical Psychology (Division 12), American Psychological Association web site http://www.div12.org/psychological-treatments/disorders/chronic-or-persistent-pain/acceptance-and-commitment-therapy-for-chronic-pain/Published. Published 2013Accessed June 1, 2015

- DindoLOne-day acceptance and commitment training workshops in medical populationsCurr Opin Psychol20152384225793217

- PagéMGStinsonJCampbellFIsaacLKatzJPain-related psychological correlates of pediatric acute post-surgical painJ Pain Res2012554755823204864

- Santa MinaDClarkeHRitvoPEffect of total-body prehabilitation on postoperative outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysisPhysiotherapy2014100319620724439570