Abstract

The treatment of failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) can be equally challenging to surgeons, pain specialists, and primary care providers alike. The onset of FBSS occurs when surgery fails to treat the patient’s lumbar spinal pain. Minimizing the likelihood of FBSS is dependent on determining a clear etiology of the patient’s pain, recognizing those who are at high risk, and exhausting conservative measures before deciding to go into a revision surgery. The workup of FBSS includes a thorough history and physical examination, diagnostic imaging, and procedures. After determining the cause of FBSS, a multidisciplinary approach is preferred. This includes pharmacologic management of pain, physical therapy, and behavioral modification and may include therapeutic procedures such as injections, radiofrequency ablation, lysis of adhesions, spinal cord stimulation, and even reoperations.

Introduction

Back pain is a highly prevalent condition that can have a tremendous social, financial, and psychological impact on a patient’s life. Low back pain is a worldwide problem, with an estimated 9.4% global incidence, creating more disability than any other condition in the world.Citation1 Prevalence of low back pain increases with age, so it is understandable that there is an increasing rate of surgeries to treat back pain in accordance with an aging population demographic. It is estimated that from 2000 to 2007, the total number of adults in the United States with chronic back pain increased by 64% (from 7.8 million to 12.8 million) with a mean age increasing from 48.5 to 52.2 years.Citation2 Considering the significant increase in the prevalence of back pain over time, it is understandable that there are similar trends in increasing rates of surgeries to treat it. Between 1998 and 2008, the annual number of hospital discharges for primary lumbar fusions increased by 170.9% from 77,682 to 210,407. During the same period, the rate of laminectomies increased by 11.3% from 92,390 to 107,790 ().Citation3 However, sometimes surgery fails to provide relief or provides only temporary relief of the patient’s pain. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) as:

Lumbar spinal pain of unknown origin either persisting despite surgical intervention or appearing after surgical intervention for spinal pain originally in the same topographical location.Citation4

Table 1 FBSS statistics

Patients with FBSS have had chronic longstanding back pain, with or without referred or radicular symptoms and have had one or more surgical interventions that have failed to treat the pain. Unfortunately, this happens all too often, with conservative estimates at 20% but other estimates as high as 40%.Citation5 A recent systematic literature review of discectomies for lumbar disc herniation in patients under the age of 70 years demonstrated a range of recurrent back or leg pain in 5%–36% of patients after 2 years.Citation6 Another prospective study by Skolasky et alCitation7 involving 260 patients who underwent a surgical laminectomy with or without fusion for lumbar spinal stenosis secondary to degenerative changes demonstrated that 29.2% of patients had either no change or increased pain after 12 months. Improved outcomes associated with FBSS will rely more on comprehensive knowledge of the physician in order to effectively prevent, diagnose, and treat FBSS.

Etiology

FBSS may be caused by a multitude of reasons including both preoperative and postoperative risk factors ().

Table 2 Summary of factors leading to failed back surgery syndrome

Preoperative factors

Many preoperative indicators determine the likelihood of success of spinal surgery. Such indicators include the accuracy of diagnoses, socioeconomic, behavioral, and psychological factors.

Successful outcome of a surgical intervention is dependent on the accurate diagnosis of the patient’s etiology of pain. For example, the decision to undergo surgery and the type of surgery performed are different if the patient’s pain is derived from a herniated disc versus spondylolisthesis. Inaccurate diagnosing is a major factor leading to FBSS, with as much as 58% of FBSS resulting from undiagnosed lateral stenosis of the lumbar spine.Citation8 Certain diagnoses are associated with greater rates of FBSS. For example, multiple studies have shown that back pain caused by foraminal stenosis is associated with greater rates of FBSS than pain caused by recurrent disc herniation.Citation8–Citation11 Entrapment of the superior cluneal nerve is an often overlooked diagnosis in patients presenting with lower back pain with or without leg symptoms.Citation12 Accurate diagnosis is dependent on a thorough history, physical examination, and imaging. Diagnostic injections can be used to further clarify the sources of back and leg pain.

Economic influences that may act to prevent successful spinal surgical outcomes include litigation and workers’ compensation. These factors create the confounding variable of secondary gain that may hinder the patient’s motivation to improve. Multiple studies have demonstrated that patients receiving workers’ compensation respond poorly to spine surgeries compared with nonworkers’ compensation in nearly all outcome variables including postoperative pain levels, postoperative opioid use, functional ability after surgery including ability to work, and overall emotional well-being.Citation13–Citation15

Behavioral factors may act to affect postoperative outcome after spine surgery. A large prospective cohort study involving 4,555 patients who had spine surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis demonstrated that smokers had a more regular use of analgesics, worsened walking ability, and inferior overall quality of life 2 years after surgery compared with nonsmokers.Citation16 Smoking is also associated with an increased rate of perioperative complications such as impaired wound healing, increased rate of infections, and an increased rate of nonunion in spinal fusions.Citation17–Citation19 These results demonstrate the importance of encouraging behavioral modification in order to optimize the patient for postoperative success. This emphasis can be applied to multiple facets of life including maintenance of body habitus and optimization of emotional disposition prior to surgery.Citation20,Citation21 Optimization of this variable may require preoperative consultations with nutrition and physical medicine and rehabilitation to create healthy habits that will last into the postoperative phase of the patient’s recovery.

Psychological evaluation to assess for these risks factors may play a key role in recognizing the predictive value of a patient’s success after spinal surgery. Multiple studies have demonstrated that depression is one of the strongest prognostic indicators of a negative outcome after spinal surgery. Depressed patients generally feel more pain and weakness as well as return to work at significantly lower rates compared with their nondepressed counterparts.Citation14,Citation22 Depression, anxiety, and other psychological and social factors may be used to assess whether the patient is a good candidate for spinal surgery. As a result, the United States Preventative Service Task Force recommends a presurgical psychological screening; however, a majority of spinal surgeons do not use such an evaluation.Citation23 More widespread use of preoperative psychological evaluations may play an important role in the prevention of FBSS.

Postoperative factors

The recurrence of back pain or the failure of back pain to resolve can be multifactorial in origin. Pain may result from further degeneration of the spinal column or new onset spinal pathology, or it can occur as a result of trauma or stress from adjacent muscles.

Back surgery often results in biomechanical changes within that region, resulting in an increased load burden within adjacent structures. This can accelerate degenerative changes in the areas of the spine both above and below the fusion.Citation24 Fusion of the lumbar spine to the sacrum as well as fusion of multiple segments may lead to sacroiliac joint (SIJ) disease.Citation25,Citation26 Degenerative changes of the spine include facet arthropathy, which can cause new onset foraminal stenosis. Changes in the intervertebral discs include disc degeneration or a new onset herniated nucleus pulposus that can lead to central or foraminal stenosis.Citation27 Stenosis can also be initiated or exacerbated by epidural adhesions that may eventually form after surgery.Citation28

Altered biomechanics from back surgery may result in increased tension on the prevertebral and postvertebral muscles directly controlling movement of the spinal column. Increased tension on these muscles can lead to stiffness, inflammation, spasms, and fatigue, which may all act to elicit pain in the paraspinal areas of the back.Citation27 These muscles may also be directly traumatized during surgery as a result of intraoperative dissection and retraction. The odds of such an event occurring may be minimized by performing fusions using the anterior approach as well as with the use of minimally invasive surgeries.Citation29,Citation30

Diagnosis

The assessment and diagnosis of FBSS always begins with eliciting a thorough history and physical examination (). The first step involves determining the severity and location of the pain. A temporal relationship between the pain and the surgery should be established. This information, compared to the patient’s presurgical pain, can help elucidate a differential diagnosis.Citation31 For example, presurgical radicular pain that persists in the immediate postoperative period may be indicative of a wrong site or incomplete surgery, whereas new onset radicular symptoms immediately after surgery may result from a misplaced screw that could warrant an immediate return to the operating room. New onset radicular symptoms in the acute postoperative period (1–5 days) may also result from a hematoma or abscess.

Table 3 Diagnostic modalities for FBSS

Longstanding pain after surgery may not be as emergent as in the acute phase but is often more difficult to assess. Physical examination findings may help create a differential diagnosis, but they are often not reliable in establishing a clear diagnosis. The only clinical examination finding that correlates with facet arthropathy is paraspinal tenderness.Citation32 Unfortunately, paraspinal tenderness is also a major clinical examination finding for myofascial pain. In addition, myofascial referred pain can be mistaken for radicular pain on physical examination.Citation33 Discogenic pain may also present as either radicular or nonradicular pain. Because of the limitations of the physical examination, the practitioner must rely on other diagnostic modalities like imaging and diagnostic procedures.

Imaging

In terms of imaging, X-rays are a simple first step in the evaluation of chronic postoperative back pain. Full spine standing flexion and extension X-rays can be used to assess spinal deformities, changes in lordosis, and sagittal balance and can demonstrate spondylolisthesis even with normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings.Citation34,Citation35 Limitations of plain film X-rays include its inability to show the spine in three dimensions as well as its inability to display soft tissue, rendering plain films inadequate in visualizing postoperative adhesions, spinal stenosis, disc deformities, and nerve root impingement.Citation31 These limitations may necessitate more advanced imaging.

The gold standard for visualization of the spine is Gadolinium-enhanced MRI.Citation36 Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images allow the practitioner to differentiate disc herniation from postsurgical fibrosis as a cause of back pain.Citation37 Although MRI is the preferred imaging modality for soft tissue visualization, computed tomography (CT) is helpful in visualizing osseous changes within the spine including facet changes and assessing the osseous dimensions of the canals.Citation38 Often times, both CT and MRI are needed for optimum evaluation of the spine, but in cases where MRI is contraindicated (implanted medical device or metal) or where implanted hardware creates artifact on MRI, CT myelography or discography may be needed.Citation39

Diagnostic procedures

Diagnostic nerve blocks

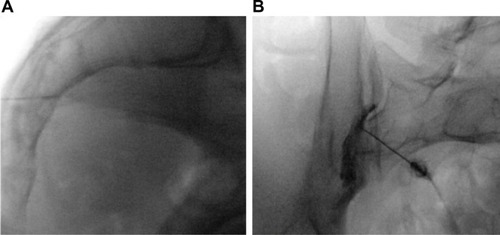

Nerve blocks can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. Selective nerve root blocks with only local anesthetic have been done historically as a mode of diagnosis and as a predictive guideline for patients considering lumbar decompression surgery despite its accuracy having been questioned.Citation40,Citation41 Adding steroid to local anesthetic can improve the duration of pain relief of injections, thus many injections can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. In some patients, both intra-articular (IA) and extra-articular (EA) injections may provide relief for those suffering from SIJ pain (). Consequently, the efficacy of IA versus EA injection is controversial.Citation42

Figure 1 Sacroiliac joint injection.

Abbreviation: AP, anteroposterior.

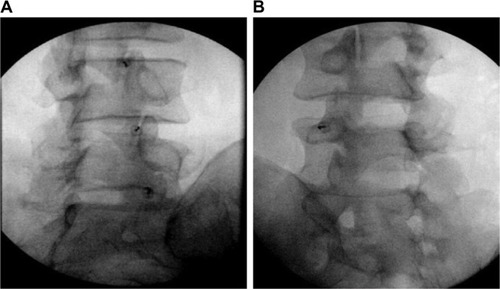

Diagnostic blocks of the facet joints have been done historically by two approaches; either by blocking the medial branches (MBs) innervating the joint or by directly injecting local anesthetic into the joint. It is widely considered that medial branch block (MBB) is a superior approach since in some patients the facet can be aberrantly innervated by other nerves. This may be a reason why MBBs are considered to be more predictive of successful radiofrequency ablation (RFA), although there have been no head to head studies directly comparing the two ().Citation32

Figure 2 Facet joint interventions.

Management of FBSS

The approach toward FBSS involves conservative management that first followed minimally invasive procedures, including injections, and finally surgical options as a last line therapy. In general, revision surgeries are not associated with improved pain scores and have a higher rate of comorbidities including increased bleeding, infections, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and longer hospital stays and even have higher mortality rates than the primary surgeries.Citation43 Careful consideration of the type of therapy most appropriate for the treatment of FBSS is dependent on the etiology of the pain, likelihood that the intervention will succeed and the associated risks with the procedure. These risks include a return of symptoms and even an exacerbation of pain. All of these factors should be discussed with the patient and a consensus between the patient and physician should be made after careful consideration of the risks and benefits.

Conservative management

Physical therapy and medication management are the cornerstone of first-line management of FBSS. Physical therapy can help the patient optimize gait and posture and can improve muscle strength and physical function.Citation44,Citation45 Other conservative measures that may help postoperative back pain involve psychotherapy measures including stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy.Citation46 Finally, noninvasive procedures including acupuncture and scrambler therapy can be used to minimize the pain associated with FBSS.Citation47,Citation48 These conservative measures should be done in conjunction with medication management to optimize pain relief.

Pharmacological management

Oral pharmacological treatment of FBSS is multimodal and increasingly controversial. Treatments include antiepileptics, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral steroids, antidepressants, and opioids. Antiepileptics such as Gabapentin and Pregabalin can be used to treat neuropathic pain with FBSS and may play a role in preventing pain after surgery.Citation49,Citation50 Chronic opioid use is associated with a multitude of side effects including immunosuppression, androgen deficiency, constipation, and depression. Chronic opioid therapy for noncancer pain is associated with an increased morbidity and mortality and does not reliably improve long-term pain and function scores. As a result, there has been an increasing push by the government and medical community to minimize or even completely avoid the use of opioids for long-term pain.Citation51

Interventional pain procedures

Epidural injections

Epidural steroid injections (ESIs) are the most commonly performed procedure in pain clinics around the world.Citation52 These can be administered primarily by three approaches: transforaminal, interlaminar, or caudally, and are indicated for symptoms of radiculopathy. Radicular symptoms in the failed back patient may be due to a multitude of reasons including herniated disc, postoperative adhesions, a thickened ligamentum flavum, spondylolisthesis with or without an associated pars defect, osteophyte formation from facet arthropathy or other degenerative changes that may lead to central or transforaminal stenosis. ESI can be a useful tool for both treating the symptoms of radicular back pain after surgery and preventing or delaying the need for surgery. A recent meta-analysis suggests that between one-third and one-half of patients considering surgery for spinal pain can avoid it in the short term with ESI, although the evidence for this is stronger in patients who have not had prior surgery.Citation53 In a separate retrospective study involving 69 patients with persistent radicular pain after back surgery, 26.8% of patients had at least 50% pain relief after transforaminal ESI. This number increased to 43% in patients with recurrent disc herniation.

Optimization of analgesia with ESIs in patients with FBSS can be achieved when performed in conjunction with pharmacologic agents aimed at treating neuropathic pain. Zencirci et alCitation54 demonstrated that adding Gabapentin to ESI in patients with FBSS from at least two prior surgeries for lumbar disc herniation had significantly lower pain levels at 1 and 3 months compared with those who received ESI while taking naproxen sodium, tizanidine, and vitamin B and C complex.Citation54 This study underlies the importance of a multimodal approach to treating FBSS.

Adhesiolysis

Postoperative scar formation is a natural part of tissue healing after any surgery. Naturally, spine surgery will result in the formation of fibrotic adhesions within the epidural space. These adhesions may cause back and leg pain by compressing nerve roots, decreasing range of motion in the back and inducing pain with movement. Adhesions may contribute to or cause 20%–36% of FBSS cases and may act to compromise the efficacy of ESI by creating septations within the epidural space that prevent steroid from acting on its intended target.Citation31,Citation55 Adhesions can theoretically be lysed, thereby improving baseline pain scores and drug delivery of the ESI. Lysis of adhesions typically occurs by delivering hyaluronidase with hypertonic saline into the epidural space. The use of hyaluronidase with steroid may be more effective and have longer duration of effect than either one alone.Citation56 Lysis of adhesion can also be done by means of epiduroscopy, which may allow the physician to directly visualize the adhesions in the epidural space. In a systematic review performed by Helm et al,Citation57 seven randomized control trials and three observational studies of 45 studies that met criteria demonstrated that Level I or strong evidence that percutaneous lysis of adhesions is efficacious in the treatment of chronic back and extremity pain, with weaker Level II or III evidence for epiduroscopy based on one RCT and three observational studies.

Radiofrequency ablation

RFA of nerves are often used to provide sustained relief that a diagnostic block or therapeutic injection cannot provide. Successfully targeting the intended nerve is achieved, maximizing the size of the lesion. This can be done by performing multiple RFA in different locations, increasing the temperature and time of the ablation, using bipolar RF or cooled RF.Citation42,Citation58 As stated earlier, MBB or facet blocks are used as a diagnostic tool for facet-mediated pain. After a positive response, an RFA of the corresponding MBs is expected to provide pain relief for 6–12 months up to 2 years.Citation59 As mentioned earlier, SIJ injections can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes with the addition of steroid often being used to prolong the analgesic effect. Patients who get effective but short-term relief from SIJ injections are optimal candidates for RFA of the S1–S3 lateral branches and L5 dorsal ramus innervating the SIJ.Citation42

Neuromodulation

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is a treatment modality that has shown tremendous potential in the management of FBSS. The advent of SCS came just 2 years after Melzak and Wall’s 1965 groundbreaking paper on Gate Theory with Shealy and Mortimer’s case study on the complete elimination of pain in a 70-year-old male with metastatic bronchogenic carcinoma by means of electrical stimulation of the dorsal columns.Citation60,Citation61 Today, the technology of SCS is more refined, and the proposed mechanism of how SCS works is believed to be more complex than just gate theory mechanics. It has been proposed that SCS-induced analgesia occurs not only by its effects on the spinal cord but supraspinal components of the central nervous system as well as by inducing descending inhibitory pathways and inhibiting pain facilitation.Citation62

The utility of SCS for pain associated with FBSS has been well-studied. The Prospective Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trial of the Effectiveness of Spinal Cord Stimulation demonstrated improved outcomes with SCS compared with conventional medical medicine (CMM) alone in the treatment of neuropathic pain from FBSS. Metric measures included pain scores, quality of life, functional capacity, and patient satisfaction.Citation63 More recently in the PRECISE Study, Zucco et alCitation64 performed an observational, multicenter, longitudinal ambispective study on 80 patients with FBSS with predominant leg pain refractory to CMM and followed them for up to 24 months after SCS. Although total societal costs increased after SCS placement, the authors concluded that SCS implantation would be cost-effective in 80%–85% when adjusting for quality-adjusted life years. This study underscores the continued costs of untreated FBSS on society as a whole, including loss of productivity, costs associated with disability, emergency room visits, imaging costs, and costs of medications and hospitalizations.Citation64 Future studies include the Prospective, randomized study of multicolumn implantable lead stimulation for predominant low back pain (PROMISE) Study, which is a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial comparing SCS + CMM with CMM alone in patients with FBSS and predominantly lower back pain. The study aims to compare the outcomes such as pain scores, functional disability, return to work, and functional utilization between the two groups. Recruitment will end in 2016.Citation65 Improved outcomes with FBSS will be expected with improving neuromodulation activities including “Burst” technology, higher frequency stimulation including 10 kHz, dorsal root ganglion stimulation, and peripheral nerve field stimulation ().

Table 4 Neuromodulation studies

Considerations for surgical revision

As mentioned earlier, surgical revision for FBSS is associated with a high morbidity with corresponding low rates of success. Arts et alCitation24 demonstrated only a 35% success rate 15 months after an instrumented fusion for the treatment of FBSS. These poor results demonstrate that the surgical option for the treatment of FBSS should be limited to last line therapy. With that being said, there are times when reoperation is mandated, such as loss of bowel or bladder function, motor weakness, and progressive neurological impairments from spinal cord injury, with relative indications being severe incapacitating radiculopathy, pseudoarthrosis, instability, and surgical hardware malfunction ().Citation39,Citation69

Table 5 Indications for revision surgery

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HoyDMarchLBrooksPThe global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 studyAnn Rheum Dis201473696897424665116

- SmithMDavisMAStanoMWhedonJMAging baby boomers and the rising cost of chronic back pain: secular trend analysis of longitudinal Medical Expenditures Panel Survey data for years 2000 to 2007J Manipulative Physiol Ther201336121123380209

- RajaeeSSBaeHWKanimLEDelamarterRBSpinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008Spine2012371677621311399

- HarveyAMClassification of chronic pain – descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain termsClin J Pain1995112163

- ThomsonSFailed back surgery syndrome – definition, epidemiology and demographicsBr J Pain201371565926516498

- ParkerSLMendenhallSKGodilSSSivasubramanianPCahillKZiewaczJMcGirtMJIncidence of low back pain after lumbar discectomy for herniated disc and its effect on patient-reported outcomesClin Orthop Relat Res201547361988199925694267

- SkolaskyRLWegenerSTMaggardAMRielyLH3rdThe impact of reduction of pain after lumbar spine surgery: the relationship between changes in pain and physical function and disabilitySpine201439171426143224859574

- BurtonCVKirkaldy-WillisWHYong-HingKHeithoffKBCauses of failure of surgery on the lumbar spineClin Orthop Relat Res1981157191199

- SchoffermanJReynoldsJHerzogRCovingtonEDreyfussPO’NeillCFailed back surgery: etiology and diagnostic evaluationSpine J20033540040314588953

- WaguespackASchoffermanJSlosarPReynoldsJEtiology of long-term failures of lumbar spine surgeryPain Med200231182215102214

- SlipmanCWShinCHPatelRKEtiologies of failed back surgery syndromePain Med20023320021415099254

- KuniyaHAotaYKawaiTKanekoKKonnoTSaitoTProspective study of superior cluneal nerve disorder as a potential cause of low back pain and leg symptomsJ Orthop Surg Res201491124383821

- GumJLGlassmanSDCarreonLYIs type of compensation a predictor of outcome after lumbar fusion?Spine201338544344823080428

- AndersonJTHaasARPercyRWoodsSTAhnUMAhnNUClinical depression is a strong predictor of poor lumbar fusion outcomes among workers’ compensation subjectsSpine2015401074875625955092

- NguyenTHRandolphDCTalmageJSuccopPTravisRLong-term outcomes of lumbar fusion among workers’ compensation subjects: a historical cohort studySpine201136432033120736894

- SandénBFörsthPMichaëlssonKSmokers show less improvement than nonsmokers two years after surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis: a study of 4555 patients from the Swedish spine registerSpine201136131059106421224770

- KruegerJKRohrichRJClearing the smoke: the scientific rationale for tobacco abstention with plastic surgeryPlast Reconstr Surg200110841063107311547174

- FangAHuSSEndresNBradfordDSRisk factors for infection after spinal surgerySpine200530121460146515959380

- GlassmanSDAnagnostSCParkerABurkeDJohnsonJRDimarJRThe effect of cigarette smoking and smoking cessation on spinal fusionSpine200025202608261511034645

- Marquez-LaraANandyalaSVSankaranarayananSNoureldinMSinghKBody mass index as a predictor of complications and mortality after lumbar spine surgerySpine2014391079880424480950

- MenendezMENeuhausVBotAGRingDChaTDPsychiatric disorders and major spine surgery: epidemiology and perioperative outcomesSpine2014392E111E12224108288

- McKillopABCarrollLJBattiéMCDepression as a prognostic factor of lumbar spinal stenosis: a systematic reviewSpine J201414583784624417814

- YoungAKYoungBKRileyLH3rdSkolaskyRLAssessment of presurgical psychological screening in patients undergoing spine surgery: use and clinical impactJ Spinal Disord Tech2014272767923197256

- ArtsMPKolsNIOnderwaterSMPeulWCClinical outcome of instrumented fusion for the treatment of failed back surgery syndrome: a case series of 100 patientsActa Neurochir201215471213121722588339

- UnokiEAbeEMuraiHKobayashiTAbeTFusion of multiple segments can increase the incidence of sacroiliac joint pain after lumbar or lumbosacral fusionSpine Epub20151218

- KatzVSchoffermanJReynoldsJThe sacroiliac joint: a potential cause of pain after lumbar fusion to the sacrumJ Spinal Disord Tech2003161969912571491

- RigoardPBlondSDavidRMertensPPathophysiological characterisation of back pain generators in failed back surgery syndrome (part B)Neurochirurgie201561Suppl 1S35S4425456443

- HsuEAtanelovLPlunkettARChaiNChenYCohenSPEpidural lysis of adhesions for failed back surgery and spinal stenosis: factors associated with treatment outcomeAnesth Analg2014118121522424356168

- ZdeblickTADavidSMA prospective comparison of surgical approach for anterior L4–L5 fusion: laparoscopic versus mini anterior lumbar interbody fusionSpine200025202682268711034657

- MobbsRJSivabalanPLiJMinimally invasive surgery compared to open spinal fusion for the treatment of degenerative lumbar spine pathologiesJ Clin Neurosci201219682983522459184

- ChanC-wPengPFailed back surgery syndromePain Medicine201112457760621463472

- CohenSPHuangJHYBrummettCFacet joint pain—advances in patient selection and treatmentNat Rev Rheumatol20139210111623165358

- ShapiroCMThe failed back surgery syndrome: pitfalls surrounding evaluation and treatmentPhys Med Rehabil Clin N Am201425231934024787336

- AssakerRZairiFFailed back surgery syndrome: to re-operate or not to re-operate? A retrospective review of patient selection and failuresNeurochirurgie201561Suppl 1S77S8225662850

- KizilkilicOYalcinOSenOAydinMVYildirimTHurcanCThe role of standing flexion-extension radiographs for spondylolisthesis following single level disk surgeryNeurol Res200729654054317535575

- DesaiMJNavaARigoardPShahBTaylorRSOptimal medical, rehabilitation and behavioral management in the setting of failed back surgery syndromeNeurochirurgie201561Suppl 1S66S7625456441

- BabarSSaifuddinAMRI of the post-discectomy lumbar spineClin Radiol2002571196998112409106

- EunSSLeeHYLeeSHKimKHLiuWCMRI versus CT for the diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosisJ Neuroradiol201239210410921489629

- HussainAErdekMInterventional pain management for failed back surgery syndromePain Practice2014141647823374545

- DattaSManchikantiLFalcoFJDiagnostic utility of selective nerve root blocks in the diagnosis of lumbosacral radicular pain: systematic review and update of current evidencePain Physician2013162 SupplSE97S12423615888

- BeynonRHawkinsJLaingRThe diagnostic utility and cost-effectiveness of selective nerve root blocks in patients considered for lumbar decompression surgery: a systematic review and economic modelHealth Technol Assess20131719188

- CohenSPChenYNeufeldNJSacroiliac joint pain: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatmentExpert Rev Neurother20131319911623253394

- DieboBGPassiasPGMarascalchiBJJalaiCMWorleyNJErricoTJLafageVPrimary versus revision surgery in the setting of adult spinal deformity: a nationwide study on 10,912 patientsSpine201540211674168026267823

- DelittoAPivaSRMooreCGSurgery versus nonsurgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2015162746547325844995

- KellerABroxJIGundersonRHolmIFriisAReikeråsOTrunk muscle strength, cross-sectional area, and density in patients with chronic low back pain randomized to lumbar fusion or cognitive intervention and exercisesSpine20042913814699268

- CramerHHallerHLaucheRDobosGMindfulness-based stress reduction for low back pain. a systematic reviewBMC Complement Altern Med201212116223009599

- ChoY-HKimCKHeoKHAcupuncture for acute postoperative pain after back surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsPain Pract201515327929124766648

- MarineoGIornoVGandiniCMoschiniVSmithTJScrambler therapy may relieve chronic neuropathic pain more effectively than guideline-based drug management: results of a pilot, randomized, controlled trialJ Pain Symptom Manage2012431879521763099

- KhosraviMBAzematiSSahmeddiniMAGabapentin versus naproxen in the management of failed back surgery syndrome; a randomized controlled trialActa Anæsthesiol Belg20146513137

- CanosACortLFernándezYRoviraVPallarésJBarberáMMorales-Suárez-VarelaMPreventive analgesia with pregabalin in neuropathic pain from “failed back surgery syndrome”: assessment of sleep quality and disabilityPain Med Epub2015923

- KatzJASwerdloffMABrassSDArgoffCEMarkmanJBackonjaMKatzNOpioids for chronic noncancer pain: a position paper of the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology201584141503150525846999

- ManchikantiLThe growth of interventional pain management in the new millennium: a critical analysis of utilization in the Medicare populationPain Physician20047446548216858489

- BicketMCHorowitzJMBenzonHTCohenSPEpidural injections in prevention of surgery for spinal pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsSpine J201515234836225463400

- ZencirciBAnalgesic efficacy of oral gabapentin added to standard epidural corticosteroids in patients with failed back surgeryClin Pharmacol2010220721122291506

- RahimzadehPSharmaVImaniFFaizHRGhodratyMRNikzad-JamnaniARNaderNDAdjuvant hyaluronidase to epidural steroid improves the quality of analgesia in failed back surgery syndrome: a prospective randomized clinical trialPain Physician2014171E75E8224452659

- KimSBLeeKWLeeJHKimMAAnBWThe effect of hyaluronidase in interlaminar lumbar epidural injection for failed back surgery syndromeAnn Rehabil Med201236446647322977771

- Helm IiSRaczGBGerdesmeyerLPercutaneous and endoscopic adhesiolysis in managing low back and lower extremity pain: a systematic review and meta-analysisPain Physician2016192E245E28126815254

- CostandiSGarcia-JacquesMDewsTOptimal temperature for radiofrequency ablation of lumbar medial branches for treatment of facet – mediated back painPain Pract Epub2015915

- McCormickZLMarshallBWalkerJMcCarthyRWalegaDRLong-Term Function, Pain and Medication Use Outcomes of Radiofrequency Ablation for Lumbar Facet SyndromeInt J Anesth Anesth201522 pii:028

- MelzackRWallPDPain mechanisms: a new theorySurvey Anesth19671128990

- ShealyCNMortimerJTReswickJBElectrical inhibition of pain by stimulation of the dorsal columns: preliminary clinical reportAnesth Analg19674644894914952225

- GuanYSpinal cord stimulation: neurophysiological and neurochemical mechanisms of actionCurr Pain Headache Rep201216321722522399391

- KumarKTaylorRSJacquesLSpinal cord stimulation versus conventional medical management for neuropathic pain: a multicentre randomised controlled trial in patients with failed back surgery syndromePain2007132117918817845835

- ZuccoFCiampichiniRLavanoACost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis of spinal cord stimulation in patients with failed back surgery syndrome: results from the PRECISE studyNeuromodulation201518426627625879722

- RigoardPDesaiMJNorthRBSpinal cord stimulation for predominant low back pain in failed back surgery syndrome: study protocol for an international multicenter randomized controlled trial (PROMISE study)Trials201314137624195916

- de VosCCBomMJVannesteSLendersMWde RidderDBurst spinal cord stimulation evaluated in patients with failed back surgery syndrome and painful diabetic neuropathyNeuromodulation201417215215924655043

- SchuSSlottyPJBaraGvon KnopMEdgarDVesperJA prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to examine the effectiveness of burst spinal cord stimulation patterns for the treatment of failed back surgery syndromeNeuromodulation201417544345024945621

- LadSPBabuRBagleyJHUtilization of spinal cord stimulation in patients with failed back surgery syndromeSpine20143912E719E72724718057

- WaddellGKummelEGLottoWNGrahamJDHallHMcCullochJAFailed lumbar disc surgery and repeat surgery following industrial injuriesJ Bone Joint Surg Am1979612201207422604