Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the use of 5% lidocaine medicated plaster (LMP) for treating painful scars resulting from burns or skin degloving.

Patients and methods

This was a prospective, observational case series study in individuals with painful scars <70 cm2 in area, caused by burns or skin degloving. The study included a structured questionnaire incorporating demographic variables, pain evaluation using the numeric rating scale (NRS), the DN4 questionnaire, and measurement of the painful surface area. Patients with open wounds in the painful skin or with severe psychiatric disease were excluded.

Results

Twenty-one men and eight women were studied, aged (mean + standard deviation) 41.4 ± 11.0 years, with painful scars located in the upper extremity (n = 9), lower extremity (n = 19), or trunk (n = 1). Eleven patients (37.9%) had an associated peripheral nerve lesion. The scars were caused by burns (n = 13), degloving (n = 7), and/or orthopedic surgery (n = 9). The duration of pain before starting treatment with lidocaine plaster was 9.7 ± 10.0 (median 6) months. The initial NRS was 6.66 ± 1.84 points, average painful area 23.0 ± 18.6 (median 15) cm2, and DN4 score 4.7 ± 2.3 points. The duration of treatment with LMP was 13.9 ± 10.2 (median 11) weeks. After treatment, the NRS was reduced by 58.2% ± 27.8% to 2.72 ± 1.65. The average painful area was reduced by 72.4% ± 24.7% to 6.5 ± 8.6 (median 5) cm2. Nineteen patients (69%) showed functional improvement following treatment.

Conclusion

LMP was useful for treating painful scars with a neuropathic component, producing meaningful reductions in the intensity of pain and painful surface area. This is the first time that a decrease in the painful area has been demonstrated in neuropathic pain using topical therapy, and may reflect the disease-modifying potential of LMP.

Introduction

Neuropathic pain arises as a direct consequence of injury or disease affecting the somatosensory system.Citation1 Neuropathic pain may occur as a manifestation of various conditions that cause nerve damage, such as viral infections (postherpetic neuralgia), metabolic disorders (diabetes mellitus), drug-induced toxicity, inflammation, cancer, trauma, and postsurgical complications.Citation2

Lidocaine is a local anesthetic that produces nonselective blockade of both open and inactive voltage-dependent sodium channels (NaV 1.7, NaV 1.8, and NaV 1.9) in excitatory membranes responsible for nerve conduction in C and A-δ primary afferent fibers, suppressing the spontaneous and evoked abnormal activity that initiates and sustains neuropathic pain.Citation3,Citation4 5% lidocaine medicated plaster (LMP, Versatis®, Grünenthal, Germany), acts peripherally as a noninvasive topical analgesic, combining efficacy with minimal systemic absorption, a low risk of interaction with other medicinal products, and an excellent safety and tolerability profile. Several studies have provided evidence for the use of LMP in treating the neuropathic pain associated with postherpetic neuralgia.Citation5–Citation8 LMP has been included as the first-line treatment for localized peripheral neuropathic pain in many treatment recommendations for the US,Citation9 Europe,Citation10 and Latin America. Citation11 Two years ago, LMP was approved by the Hospital del Trabajador de Santiago Pharmacy Committee for use in patients with post-traumatic pain.

LMP is applied to the most painful area for 12 hours each day and then removed for 12 hours, with no need for titration. The 12-hour dosage interval is based on the results of clinical trials demonstrating that a patch-free interval reduces skin exposure and prevents unwanted local effects induced by continuous occlusion of the affected skin, but provides continuous analgesia for 24 hours.Citation12,Citation13

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of LMP in patients with painful scars of the post-traumatic/ postsurgical neuropathic type, caused by burns, degloving injuries, and surgical incisions.

Methods

An observational, open-label, clinical case series study was conducted in patients who had occupational diseases or had suffered accidents at work and were seen at the Hospital del Trabajador de Santiago in Chile from October 2008 to September 2009. Inclusion criteria were patients who had scars with a painful area measuring less than 70 cm2. Patients with open wounds or severe psychiatric illness were excluded.

A structured protocol was used, addressing demographic variables, diagnoses, causes of pain, and mental health. The DN4 questionnaireCitation14,Citation15 was used in all patients. This defines neuropathic pain as having a score of 4/10 or above. The painful area was evaluated by measuring the width and length of the region in which the patient felt pain at the time of examination, and a photographic record of the affected area was obtained. In all suspected cases of peripheral nerve injury, a neurophysiologic study was carried out.

The initial dose (number of plasters) of LMP, use of co-analgesics, and concomitant drugs were recorded. In all patients, hypoallergenic adhesive tape (Micropore®, 3M, St Paul, MN) was used to attach the plaster securely to the skin. The results of therapy were expressed as absolute and percentage changes in numerical rating scale (NRS), painful area, sleep quality, regained function, and return to work. Patients were checked monthly, and the protocol described above was used at each consultation. LMP therapy was considered effective if there was a reduction in NRS score of ≥3 points or ≥50%, and/or the painful area decreased by ≥50% compared with the start of therapy.

Each LMP contains 700 mg of lidocaine. The amount of lidocaine systemically absorbed is very low (3% ± 2% of the topical dose applied) and is directly related to the duration of application and the area of skin in direct contact with the LMP. Peak serum levels with a dose of four plasters for 12 or 24 hours, ie, in excess of the recommended dose and duration, are 225 ng/mL and 186 ng/mL, respectively, which is approximately one-seventh the concentration required for an antiarrhythmic effect (1500 ng/mL)Citation16–Citation18 and 25 times less than the toxic dose (5000 ng/mL).Citation17,Citation19,Citation20 LMP has been used in patients with heart disease and painful scars with no reports of significant side effects.Citation21 All adverse reactions have been of mild to moderate intensity. Fewer than 5% of these led to discontinuation of treatment. Patients were informed of this risk and told that, in the event of occurrence, they should discontinue use.

All patients were suitably informed about the characteristics of the medicinal product and its side effects before starting the study, and gave their consent before being included. Side effects and treatment adherence were solicited by direct questioning at each interview. The study was approved by the Hospital del Trabajador de Santiago Ethics Committee.

The analysis of quantitative variables employed the mean, standard deviation, and maximum and minimum values. Qualitative variables were summarized in terms of absolute and percentage relative frequencies. The paired Student’s t-test was used to compare mean values from the same patients examined at two time points during the investigation.

Results

Demographics

The study population consisted of 29 patients (21 men and 8 women) with a mean age of 41.4 ± 11.0 (range 23–62) years. The traumatic injuries were located on the lower limb in 19 cases (65.5%), the upper limb in nine cases (31%), and the trunk in one case. The underlying cause was diagnosed as burns in 13 cases (44.8%), postsurgical scarring in nine cases (31%), and crush and degloving injury of the extremity in seven cases (24.1%).

Pain evaluation

Involvement of peripheral nerves was observed in 11 patients (37.9%), ie, the superficial radial nerve in three patients, the peroneal nerve in two, the sural nerve in two, and the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, the palmar branch of the median nerve, the collateral palmar nerves, and the saphenous nerve in one patient each. Pain intensity (NRS) at the start of the study was 6.66 ± 1.84 (median 7, range 4–10 points). Fifteen patients (51.7%) had pain scores of ≥7. The duration of pain prior to starting LMP treatment was 9.7 ± 10.0 months (median six months, range one month to 2.8 years). In seven patients (24.1%) the duration of pain was less than three months, in 15 (51.7%) it was 3–12 months, and in 7 (24.1%) it was more than 12 months.

Painful area and doses employed

At the start of the study, the mean size of the painful area was 23 cm2 (median 15 cm2, range 8–70 cm2). In all patients, the plaster was applied to the painful area. Five patients used half a plaster and the other 24 used a quarter of a plaster daily.

Presence of neuropathic pain

Using the DN4 questionnaire, the mean score for the study population was 4.7 ± 2.3 points. Twenty-one patients had a score of ≥4, including the 11 patients with a peripheral nerve lesion.

Comorbidity

Twenty-one patients (72.4%) required treatment for accident-related psychiatric illness. The diagnoses were adjustment, anxiety, depressive, or mixed disorder in 13 cases, post- traumatic stress disorder in four cases, and major depression in four cases.

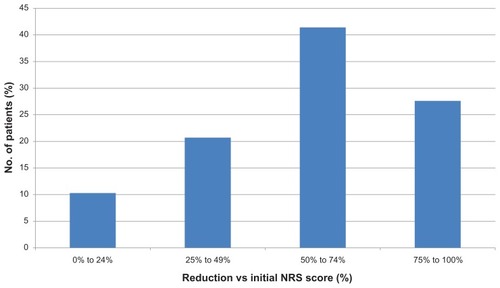

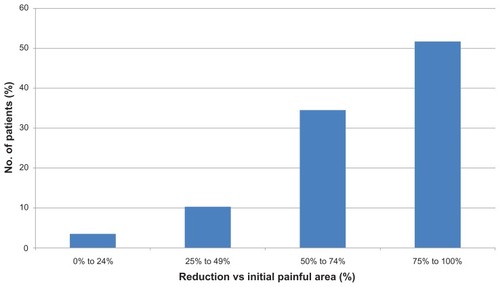

Change in pain

After 13.9 ± 10.2 weeks of treatment (median 11 weeks, range 4–45 weeks), the mean reduction in NRS was 2.72 ± 1.64 points (median 3 points, range 0–5 points). This is equivalent to a reduction of 58.2% ± 27.8% compared with baseline pain intensity (see ). In 22 patients (75.9%) the NRS score fell by ≥3 points; in 20 patients (69%), the NRS score was reduced by ≥50% after LMP treatment (see ), and no patient still had an NRS score of ≥7. The painful area decreased by 16.5 ± 13.7 cm2 (median 11 cm2, statistically significant by the paired Student t-test, P < 0.0005). This is equivalent to a mean reduction of 72.4% ± 24.7% (see ). In 25 patients (86.2%), the painful area was reduced by ≥50% (see ). Three patients (10.3%) noticed a significant improvement in sleep quality, and 17 patients (58.6%) reported significant functional recovery during LMP use (see ).

Figure 1 Percentage reduction in pain score (NRS) in patients treated with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster (LMP).

Figure 2 Percentage reduction in painful area in patients treated with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster (LMP).

Table 1 Percentage reductions in pain score and painful area in patients treated with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster

Table 2 Functional improvement in patients treated with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster

Comparison of patients with nociceptive and neuropathic pain

This study relates to painful scars, not postsurgical neuropathic pain, and it is difficult to document a nerve lesion in neuropathic pain associated with a scar. However, the DN4 questionnaire is an adequate clinical tool for differentiating between nociceptive and neuropathic pain. The eight patients (27.6%) with nociceptive pain according to the DN4 questionnaire (score < 4) had moderate to severe pain (NRS = 6) and intense stabbing pain, in one case associated with allodynia.

Before starting treatment with LMP, the duration of pain was shorter in the nociceptive pain group than in the neuropathic pain group (median three months versus seven months), and the painful area was smaller (median 10.8 cm2 versus 18.0 cm2). The NRS scores were similar. The length of treatment until maximum pain relief was shorter in the nociceptive pain group (median 9.2 weeks versus 12 weeks). After LMP treatment, the NRS scores were similar in both groups, as were the percentage of patients that reduced their NRS by ≥3 points, the average size of the painful area, the percentage reduction in size of the painful area, and the percentage of patients with a reduction of ≥50% in the size of the painful area. It can be concluded that there were few differences between the two groups in their response to LMP treatment, and none was significant.

Occupational impact

Before the pain-related accident, all the patients were in active employment. Twenty-seven patients (93%) returned to work after the accident. In patients who started LMP therapy after going back to work, functional improvement with an impact on occupational performance was observed in 12/15 cases (80%, see ).

Table 3 Occupational impact of 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in active patients

Change in concomitant analgesic medication

Fourteen patients (48.3%) were using oral analgesics, including paracetamol and tramadol, when they began treatment with LMP. No other medication was added after this point. The oral analgesics were progressively withdrawn as the patients achieved pain relief, and by the end of the study 18 patients (62%) were using LMP therapy alone. Given that oral analgesics had been taken previously for at least three months with limited benefit, the improvement in pain relief was considered to be due to LMP therapy. Two patients were taking pregabalin (150 mg/day) when they started LMP; one discontinued its use during the study while the other continued taking it throughout.

Tolerability

None of the patients in the case series suffered any local or systemic adverse reactions to LMP use.

Treatment adherence

Patients’ adherence to treatment was excellent in all cases.

Discussion

The presence of chronic pain following trauma or surgery is a common event. The exact frequency, prevalence, and natural history of these painful neuropathies are not yet known.Citation21 According to Hans et alCitation21 postoperative/post-traumatic neuropathic chronic cutaneous pain may follow any surgical incision. It is associated with touch-evoked allodynia, hyperalgesia, and paroxysms of spontaneous (nonevoked) pain that significantly impair the patient’s quality of life, and often tends to become chronic.

The analgesic efficacy of LMP has previously been demonstrated in acute and chronic forms of peripheral neuropathy, such as postherpetic neuralgiaCitation22 and diabetic polyneuropathy.Citation23 To date, two studies have been published on the use of LMP in post-traumatic pain.Citation21,Citation24 The firstCitation24 reported five cases of severe localized neuropathic scar pain, all of more than one year’s duration. After 12–16 weeks, pain intensity was reduced to mild in two cases, and pain ceased completely in another two cases. In one case, pain remained at the same intensity and then ceased spontaneously.Citation24 The second studyCitation21 evaluated the use of LMP in 40 patients with severe chronic post-traumatic cutaneous pain of surgical and nonsurgical origin. A significant reduction in pain intensity was observed at four and 12 weeks.Citation21

The prospective study by Hans et alCitation21 strongly suggests that LMP offers a novel therapy for postsurgical and post-traumatic localized neuropathic pain syndromes. The authors stressed that the analgesic response developed over a long period. In our study, LMP was effective in managing localized postsurgical and post-traumatic neuropathic pain. The pain relief provided by LMP improved occupational performance in two-thirds of our patients after their return to work. A high level of patient satisfaction was observed, because of ease of use and lack of side effects. Published analyses have shown LMP to be a cost-effective method for treating localized neuropathic pain relative to pregabalin or gabapentin.Citation25,Citation26 However, further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of LMP and oral therapies in these patients, by comparing savings in the time taken as sick leave.

Our series differs from that of Hans et alCitation21 because our patients had localized post-traumatic pain and were 15 years younger on average. Pain relief was higher in our study, with a 58.2% reduction in pain intensity, rather than 36%. Our study also measured the painful area, which was significantly reduced in patients receiving LMP therapy. LMP has been shown to decrease the area of hyperalgesia induced by capsaicin or sunburn in healthy volunteers,Citation27 and oral adenosine,Citation28 mexiletine,Citation29 and rofecoxibCitation30 can reduce the painful area, but this is the first time the effect has been demonstrated in patients with neuropathic pain using topical therapy. Such an effect has important functional implications, especially if the painful area is located on the palm of the hand or sole of the foot. LMP may directly affect peripheral sensitization and modulate the impact of neuropathic pain. This could possibly indicate disease-modifying potential, but further investigative studies are needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LMP was shown to be a safe, effective treatment for localised post-traumatic or postsurgical neuropathic pain. Our results also suggest that LMP significantly improves patients’ functional level, and is associated with an improvement in occupational performance. However, the study is limited by the small number of patients, a nonrandomized and open design, and lack of a placebo group, so a degree of caution should be exercised when extrapolating from these results.

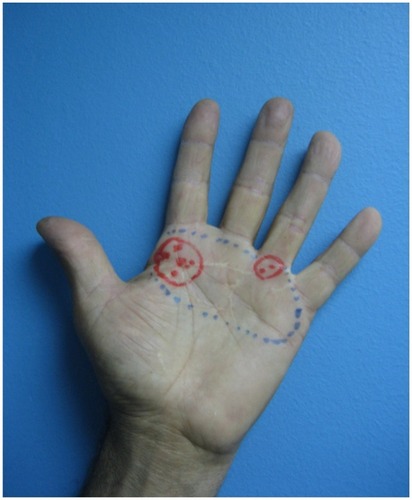

Case study

This patient is a 58-year-old male, a mechanic, who suffered a high-voltage burn (12,000 volts) to his left hand which affected the collateral nerves. This trauma produced severe (NRS 8/10), persistent, neuropathic pain (DN4 9/10) in the palm of his hand, accompanied by intense allodynia. The painful surface area (outlined in blue in ) extended over 21 cm2. Pain interrupted his sleep and interfered with his work, preventing him from manipulating the tools that he had used prior to his accident. Over a period of two years and three months, the pain proved resistant to analgesic treatment. A range of analgesic drugs and schemes were tried, both singly and in various combinations, which included gabapentin 400 mg/day, tramadol 200 mg/day, meloxicam 15 mg/day, ketoprofen 50 mg/day, and topical diclofenac. The dosage of gabapentin could not be increased owing to intolerance.

Figure 3 Painful surface area before (blue area) and after (red areas) treatment with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster (LMP).

At this point, treatment with LMP was started. Five months later, pain intensity had reduced by 63% and the painful surface area had reduced to 4.5 cm2 overall (areas outlined in red in ). The red dots indicate discomfort rather than pain (NRS 3/10 or below) and the cross indicates pain with an NRS of 4/10 or above. Allodynia had disappeared, his quality of sleep had improved significantly, and he could now manipulate tools at work without difficulty.

Acknowledgments

We thank our superiors and colleagues in the Hospital del Trabajador de Santiago Rehabilitation Department for their assistance with this study, and Derrick Garwood Ltd, Cambridge, UK, for editorial support, which was sponsored by Grünenthal GmbH, Germany.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- TreedeRDJensenTSCampbellJNNeuropathic pain: Redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposesNeurology200870181630163518003941

- HernándezJNHernándezJMorenoCUse of lidocaine patches in the relief of localised neuropathic painRev Iberoamericana del Dolor2009141328

- de Leon-CasasolaOAMultimodal approaches to the management of neuropathic pain: The role of topical analgesiaJ Pain Symptom Manag2007333356364

- WasnerGKleinertABinderASchattschneiderJBaronRPostherpetic neuralgia: Topical lidocaine is effective in nociceptor-deprived skinJ Neurol2005252667768615778907

- RowbothamMCDaviesPSVerkempinckCGalerBSLidocaine patch: Double-blind controlled study of a new treatment method for post-herpetic neuralgiaPain199665139448826488

- GalerBSRowbothamMCPeranderJFriedmanETopical lidocaine patch relieves postherpetic neuralgia more effectively than a vehicle topical patch: Results of an enriched enrolment studyPain19998053353810342414

- BinderABruxelleJRogersPHansGBöslIBaronRTopical 5% lidocaine (lignocaine) medicated plaster treatment for post-herpetic neuralgia: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational efficacy and safety trialClin Drug Investig2009296393408

- HansGSabatowskiRBinderABoeslIRogersPBaronREfficacy and tolerability of a 5% lidocaine medicated plaster for the topical treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia: Results of a long-term studyCurr Med Res Opin20092551295130519366301

- DworkinRHBackonjaMRowbothamMCAdvances in neuropathic painArch Neurol200360111524153414623723

- FinnerupNBOttoMMcQuayHJJensenTSSindrupSHAlgorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: An evidence based proposalPain2005118328930516213659

- AcevedoJCAmayaAde León CasasolaO[Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain: consensus of a group of Latin American experts]Rev Iberoamericana del Dolor200821546

- HaanpääMMechanism-based treatment of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgiaEur J Pain200711138

- RehmSBinderABaronRPost-herpetic neuralgia: 5% lidocaine medicated plaster, pregabalin, or a combination of both? A randomized, open, clinical effectiveness studyCurr Med Res Opin20102671607161920429825

- BouhassiraDAttalNAlchaarHComparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagn ostic questionnaire (DN4)Pain20051141–2293615733628

- PerezCGalvezRHuelbesSValidity and reliability of the Spanish version of the DN4 (Douleur Neuropathique 4 questions) questionnaire for differential diagnosis of pain syndromes associated to a neuropathic or somatic componentHealth Qual Life Outcomes200756618053212

- BenowitzNLMeisterWClinical pharmacokinetics of lignocaineClin Pharmacokinet197833177201350470

- EstesNAManolisASGreenblattDJGaranHRuskinJNTherapeutic serum lidocaine and metabolite concentrations in patients undergoing electrophysiologic study after discontinuation of intravenous lidocaine infusionAm Heart J19891175106010642711965

- JürgensGGraudalNAKampmannJPTherapeutic drug monitoring of antiarrhythmic drugsClin Pharmacokinet20034264766312844326

- GianellyRvon der GroebenJOSpivackAPHarrisonDCEffect of lidocaine on ventricular arrhythmias in patients with coronary heart diseaseN Engl J Med196727723121512194862377

- LieKIWellensHJJvan CapelleFJDurrerDLidocaine in the prevention of primary ventricular fibrillation: A double-blind, randomized study of 212 consecutive patientsN Engl J Med197429125132413264610392

- HansGJoukesEVerhulstJVercauterenMManagement of neuropathic pain after surgical and non-surgical trauma with lidocaine 5% patches: Study of 40 consecutive casesCurr Med Res Opin200925112737274319788351

- DaviesPSGalerBSReview of 5% lidocaine medicated plaster studies in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgiaDrugs200464993794715101784

- BarbanoRLHermannDNHart-GouleauSPennella-VaughanJLodewickPADworkinRHEffectiveness, tolerability and impact on quality of life of the 5% lidocaine patch in diabetic polyneuropathyArch Neurol200461691491815210530

- NayakSCunliffeMCase report: Lidocaine 5% patch for localized chronic neuropathic pain in adolescents: Report of five casesPediatric Anesthesia200818655455818363625

- LiedgensHHertelNGabrielACost-effectiveness analysis of a 5% lidocaine medicated plaster compared with gabapentin and pregabalin for treating postherpetic neuralgia: A German perspectiveClin Drug Investig2008289583601

- RitchieMLiedgensHNuijtenMCost effectiveness of a 5% lidocaine medicated plaster compared with pregabalin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia in the UK: A Markov model analysisClin Drug Investig20103027187

- GustorffBTopical lidocaine – experimental models of neuropathic pain and implications for symptomatic treatmentEur J Pain200711S1S55

- SjölundKFSegerdahlMSolleviAAdenosine reduces secondary hyperalgesia in two human models of cutaneous inflammatory painAnesth Analg199988360561010072015

- AndoKWallaceMSBraunJSchulteisGEffect of oral mexiletine on capsaicin-induced allodynia and hyperalgesia: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover studyReg Anesth Pain Med200025546847411009231

- SychaTAnzenhoferSLehrSRofecoxib attenuates both primary and secondary inflammatory hyperalgesia: A randomized, double blinded, placebo controlled crossover trial in the UV-B pain modelPain2005113331632215661439