Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), first described in 1834, is an X-linked dystrophinopathy, leading to early onset skeletal muscle weakness. Life expectancy is reduced to early adulthood as a result of involvement of voluntary skeletal muscles with respiratory failure, orthopedic deformities, and associated cardiomyopathy. Given its multisystem involvement, surgical intervention may be required to address the sequelae of the disease process. We present a 36-year-old adult with DMD, who required anesthetic care during surgical debridement of an ischial pressure sore. Given his significant respiratory muscle involvement, ultrasound-guided caudal epidural anesthesia was used instead of general during the surgical procedure. The technique and its applications are discussed, with particular emphasis on the feasibility and safety of using regional anesthetic techniques in patients with DMD.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an X-linked disorder, is the most common form of muscular dystrophy. It results from mutations in the dystrophin gene, located on chromosome Xp21.1.Citation1 Dystrophin is an integral protein in regulation of the integrity of sarcolemma. Mutations resulting in either dysfunction or total absence of this protein, result in interruption of the sarcolemma with progressive myofibril atrophy, necrosis, and fibrosis.Citation2,Citation3 DMD patients develop progressive neuromuscular weakness, skeletal deformities, and cardiopulmonary complications, with cardiac or respiratory failure being the primary cause of death during the second and third decades of life.Citation4 Patients with DMD may present for surgical procedures to correct progressive orthopedic deformities resulting from the disease process. Given the associated respiratory and cardiac involvement, anesthetic care remains challenging.Citation2,Citation5 Patients with DMD are especially susceptible to the adverse effects of general anesthesia and procedural sedation. Specific concerns that may arise include difficult endotracheal intubation, prolonged neuromuscular blockade, the need for postoperative ventilation, and hyperkalemia, rhabdomyolysis, and cardiac arrhythmias resulting from prolonged exposure to volatile anesthetic agents.Citation4,Citation5 To avoid the aforementioned perioperative risks, regional anesthetic techniques may be considered as an alternative to general anesthesia. We present the use of caudal epidural anesthesia as an alternative to general anesthesia in a 36-year-old man with DMD who presented for debridement of an ischial pressure injury. The use of regional anesthesia in this patient population is discussed, and techniques for catheter placement reviewed.

Case report

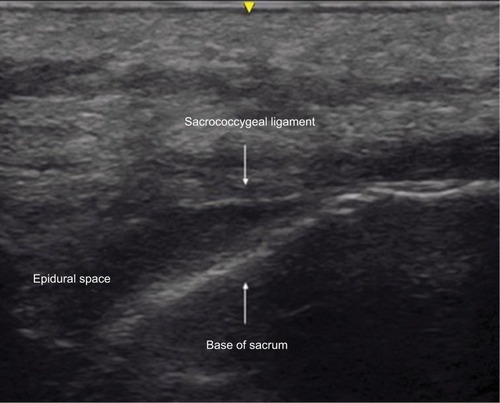

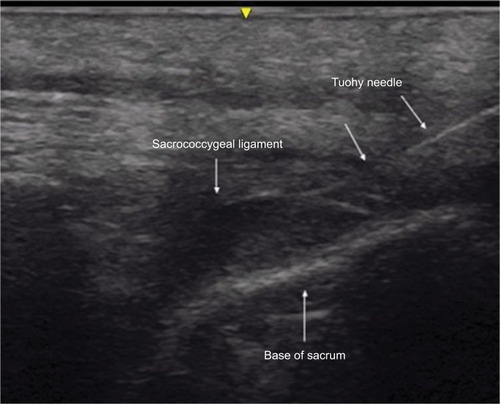

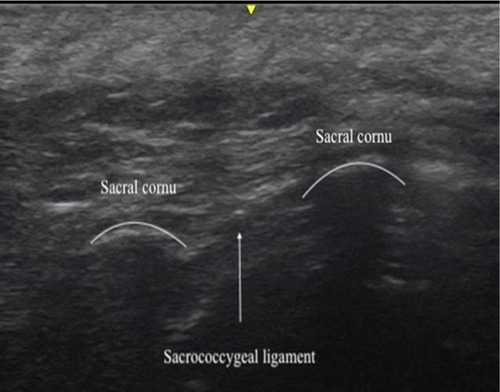

Written, informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. Institutional Review Board (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA) approval is not required for publication of isolated case reports. The patient was a 36-year-old, 61.1 kg adult, scheduled for surgical debridement of a right ischial pressure ulcer at an unspecified stage (ICD code: L89.319). His past history was positive for DMD; restrictive lung disease with chronic respiratory failure requiring Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP) support at night and Sipper ventilator support during the day. He also had a history of dysphagia and swallowing dysfunction with pulmonary aspiration resulting in gastric tube dependence. Echocardiography showed normal cardiac anatomy with mild left ventricular systolic dysfunction and an ejection fraction of 53%. His past surgical history was significant for posterior spinal fusion and gastrostomy, during which there was no history of problems with general anesthesia other than difficult vascular access. He had no known allergies. Medication included ranitidine (150 mg twice a day), sertraline (100 mg, once a day), metoprolol tartrate (25 mg, twice a day), enalapril (10 mg, twice a day), sennosides-docusate (once a day), polyethylene glycol (17 g, once a day), and multivitamin supplements. Physical examination revealed a thyromental distance of more than three fingerbreadths and a Mallampati Class I airway. There was limited range of motion (flexion and extension) of the neck. A thoracolumbar surgical scar from the previous posterior spinal fusion was noted on his back, and the spinous processes from T2 to L5 could not be palpated. The remainder of the physical examination and preoperative vital signs were unremarkable. After review of the patient’s current status of a difficult airway and significant restrictive lung disease requiring ventilator dependence, previous history of associated comorbid conditions, and after discussion with consulting services, it was decided to offer regional instead of general anesthesia. This patient had difficult anatomy for lumbar epidural of spinal anesthesia because of the fused spinous processes from his prior spinal fusion surgery and dense scar tissue on the back. The spinous processes from T2 to L5 were not felt and appropriate landmark palpation was not possible due to adipose tissue over the sacral area. Given the patient’s previous history of posterior spinal fusion and his difficult anatomy, it was decided that the best option for neuraxial anesthesia would be caudal epidural anesthesia with ultrasound guidance. The anesthetic plan, risks, benefits, and options including caudal epidural anesthesia were discussed with the patient and informed consent obtained. On the day of surgery, the patient was held nil per os and gastric tube feeding were held for 8 hours. His usual morning doses of sertraline and ranitidine were administered through the gastric tube while the enalapril was held. He was transferred to the operating room with his BiPAP machine using his usual night-time settings (20/4 cmH2O). He was positioned in left lateral decubitus position, standard American Society of Anesthesiologists monitors were placed, and ultrasound-guided peripheral intravenous access was achieved. Midazolam (a total of 4 mg in divided doses) was administered intravenously for anxiolysis. After sterile preparation, superficial anesthesia of the skin and subcutaneous tissue was achieved with 1% lidocaine. Ultrasound imaging (GE 12L-RS linear transducer, GE Medical Systems Co., Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China) of the sacral hiatus was performed in the transverse and longitudinal views ( and ). Ultrasound imaging of the sacral area also demonstrated the sacral hiatus displaced ~4–5 cm toward the right from the midline. On the first attempt, a 3.5 inch, 17-gauge Tuohy needle (Epimed Spirol® Epidural Set, Epimed International Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) was advanced under ultrasound guidance toward and through the sacrococcygeal ligament into the caudal epidural space (). A 19-gauge epidural catheter was advanced through the needle and into the epidural space. The Tuohy needle was removed and 10 cm of the catheter left in the caudal epidural space and secured in place. An initial bolus dose of 5 mL of 3% chloroprocaine was administered. After 5 minutes, sensory changes were noted to pin prick and temperature test in the lower extremities with no systemic complaints. An additional 10 mL of 3% chloroprocaine was administered and adequate surgical anesthesia was achieved over the sacral dermatomes. During the procedure, the patient received one additional bolus of 5 mL of 3% chloroprocaine, 15 minutes after the start of the procedure. No significant changes were noted in heart rate or blood pressure with the administration of the epidural medications. The only other intraoperative medication was intravenous acetaminophen (1,000 mg) for postoperative analgesia. The surgical procedure, which lasted ~30 minutes, was completed with minimal blood loss and no intraoperative complications. The patient remained on nasal BiPAP until the end of the procedure. Following completion of the surgical procedure, the caudal epidural catheter was removed in the operating room. The patient’s postoperative course was unremarkable. He remained as an inpatient for wound care and underwent a second brief procedure, which was performed with the administration of local anesthetic to the surgical site, 1 week after the first procedure. He was discharged home the day following the second procedure.

Figure 1 Transverse ultrasound image of the sacrum at the level of the sacrococcygeal ligament showing the ligament and the sacral cornu.

Discussion

Caudal epidural anesthesia, with the injection of a local anesthetic agent into the epidural space through the sacral hiatus, is commonly used to provide postoperative analgesia in pediatric patients.Citation6,Citation7 The technique may also be used instead of general anesthesia to avoid potential perioperative complications in patients with comorbid conditions.Citation8 Although the lumbar approach to the epidural space is frequently chosen for surgical anesthesia in older patients, the caudal approach may be used when previous surgical procedures or anatomical deformities preclude the lumbar approach. Such was the case in our patient, as he had previously undergone posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation which limited access to the lumbar epidural space.

Needle or catheter placement for caudal epidural anesthesia may be achieved using superficial anatomical landmarks or fluoroscopy-guided or ultrasound-guided techniques.Citation9–Citation11 Klocke et alCitation10 first described the use of ultrasound to achieve caudal epidural access for the administration of epidural corticosteroids. Although frequently performed in children using a blind approach with palpation of bony landmarks on the sacrum, given our patient’s body habitus, his previous surgical procedure on the lumbosacral spine, and difficulties with palpation of sacral bony landmarks, we chose to use ultrasound to identify the site of needle entry and guide insertion of the needle into the caudal epidural space.

Anesthesia-related concerns in patients with DMD include potential difficulties with airway management and endotracheal intubation, restrictive pulmonary disease, cardiac muscle involvement with cardiomyopathy, and the potential for adverse effects associated with the prolonged administration of inhalational anesthetic agents.Citation5,Citation12–Citation15 Given these concerns, regional anesthesia has been used as a means of avoiding general anesthesia and its potential complications in patients with DMD ().Citation16–Citation20 As with our patient, these anecdotal reports demonstrate the feasibility of using various regional anesthetic techniques instead of general anesthesia in this patient population.

Table 1 Reports of regional instead of general in DMD patients

Caudal epidural anesthesia is achieved by the injection of a local anesthetic agent into the epidural space. Potential complications associated with caudal epidural anesthesia include those related to needle placement and those from the local anesthetic agent.Citation21–Citation23 Complications related to needle placement include dural puncture, bleeding, infection, and trauma to neural elements or the spinal cord. Coagulation parameters including platelet count should be evaluated prior to needle placement. Given our patient’s previous surgical procedure involving the lumbar spine and his anatomical challenges, we chose the caudal approach to the epidural space with ultrasound guidance to limit the potential for complications related to needle placement. Complications related to the local anesthetic agent include local anesthetic systemic toxicity, cardiovascular effects from sympathetic blockade, and high motor blockade with respiratory effects. Slow incremental injection is recommended especially in patients with comorbid cardiac involvement to allow for monitoring of potential hemodynamic effects (hypotension and bradycardia). Judicious fluid administration or administration of a vasoactive agent may be needed to treat hemodynamic changes. To achieve the rapid onset of epidural anesthesia and limit the potential for systemic toxicity, given its rapid systemic metabolism, we chose to use chloroprocaine.Citation24 An additional concern regarding placement of a caudal epidural catheter vs lumbar or thoracic placement is the potential risk of infection given its location in the sacral dermatomes and risk of fecal soiling and contamination. As with all placement techniques, adequate skin preparation and coverage with a bio-occlusive dressing may help limit the potential for such concerns. Furthermore, subcutaneous tunneling has been suggested as an option when caudal epidural catheters are left in place for prolonged postoperative use.Citation25 This approach was not utilized in our patient as short-term intraoperative use of the catheter was planned.

We present the use of caudal epidural anesthesia in a patient with DMD and significant respiratory involvement to avoid the potential risks and perioperative complications associated with general anesthesia. Given previous spinal surgery with fusion and instrumentation, we chose a caudal approach to the epidural space. Ultrasound guidance was used to guide needle and catheter placement due to limited ability to identify anatomical landmarks. Our report adds additional anecdotal experience to that previously reported demonstrating the potential efficacy of using regional anesthesia instead of general anesthesia in this challenging patient population.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KunkelLMMonacoAPMiddlesworthWOchsHDLattSASpecific cloning of DNA fragments absent from the DNA of a male patient with an X chromosome deletionProc Natl Acad Sci U S A19858214477847822991893

- HopkinsPMAnaesthesia and the sex-linked dystrophies: between a rock and a hard placeBr J Anaesth2010104439740020228183

- OhlendieckKMatsumuraKIonasescuVVDuchenne muscular dystrophy: deficiency of dystrophin-associated proteins in the sarcolemmaNeurology19934347958008469343

- ConnuckDMSleeperLAColanSDCharacteristics and outcomes of cardiomyopathy in children with Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy: a comparative study from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy RegistryAm Heart J2008155998100518513510

- CripeLHTobiasJDCardiac considerations in the operative management of the patient with Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophyPaediatr Anaesth201323977778423869433

- CampbellMFCaudal anesthesia in childrenJ Urol193330245250

- SchlossBMartinDTripiJKlingeleKTobiasJDCaudal epidural blockade for major orthopedic hip surgery in adolescentsSaudi J Anaesth20159212813125829898

- TobiasJDHerseySContinuous caudal anaesthesia during inguinal hernia repair in an awake, 1440 g infantPediatric Anesthesia199443187189

- RenfrewDLMooreTEKatholMHEl-KhouryGYLemkeJHWalkerCWCorrect placement of epidural steroid injections: fluoroscopic guidance and contrast administrationAJNR Am J Neuroradiol1991125100310071719788

- KlockeRJenkinsonTGlewDSonographically guided caudal epidural steroid injectionsJ Ultrasound Med200322111229123214620894

- ChenCPTangSFHsuTCUltrasound guidance in caudal epidural needle placementAnesthesiology2004101118118415220789

- RubianoRChangJLCarrollJSonbolianNLarsonCEAcute rhabdomyolysis following halothane anesthesia without succinylcholineAnesthesiology19876758568573674501

- ChalkiadisGABranchKGCardiac arrest after isoflurane anaesthesia in a patient with Duchenne’s muscular dystrophyAnaesthesia199045122252316833

- NathanAGaneshAGodinezRINicolsonSCGreeleyWJHyperkalemic cardiac arrest after cardiopulmonary bypass in a child with unsuspected duchenne muscular dystrophyAnesth Analg2005100367267415728050

- HayesJVeyckemansFBissonnetteBDuchenne muscular dystrophy: an old anesthesia problem revisitedPaediatr Anaesth200818210010618184239

- MolyneuxMKAnaesthetic management during labour of a manifesting carrier of Duchenne muscular dystrophyInt J Obstet Anesth2005141586115627543

- BangSUKimYSKwonWJLeeSMKimSHPeripheral nerve blocks as the sole anesthetic technique in a patient with severe Duchenne muscular dystrophyJ Anesth201630232032326721827

- SoMSugiuraTYoshizawaSSobueKTwo cases of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy that showed different reactions to nerve stimulation during peripheral nerve block: a case reportA A Case Rep201792525328459722

- VandepitteCGautierPBellenPMurataHSalvizEAHadzicAUse of ultrasound-guided intercostal nerve block as a sole anaesthetic technique in a high-risk patient with Duchenne muscular dystrophyActa Anaesthesiol Belg2013642919424191530

- BügetMİErenİKüçükaySMiBRegional anaesthesia in a Duchenne muscular dystrophy patient for upper extremity amputationAgri201426419119525551817

- BorghiBCasatiAIuorioSFrequency of hypotension and bradycardia during general anesthesia, epidural anesthesia, or integrated epidural-general anesthesia for total hip replacementJ Clin Anesth20021410210611943521

- HorlockerTTComplications of spinal and epidural anesthesiaAnesthesiol Clin North America200018246148510935019

- TanakaKWatanabeRHaradaTDanKExtensive application of epidural anesthesia and analgesia in a university hospital: incidence of complications related to techniqueReg Anesth199318134388448096

- VenezianoGIlievPTripiJContinuous chloroprocaine infusion for thoracic and caudal epidurals as a postoperative analgesia modality in neonates, infants, and childrenPaediatr Anaesth2016261849126530835

- BubeckJBoosKKrauseHThiesKCSubcutaneous tunneling of caudal catheters reduces the rate of bacterial colonization to that of lumbar epidural cathetersAnesth Analg200499368969315333395