Abstract

Introduction

Needlestick injuries (NSIs) from a contaminated needle put healthcare workers (HCWs) at risk of becoming infected with a blood-borne virus and suffering serious short- and long-term medical consequences. Hypodermic injections using disposable syringes and needles are the most frequent cause of NSIs.

Objective

To perform a systematic literature review on NSI and active safety-engineered devices for hypodermic injection.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and COCHRANE databases were searched for studies that evaluated the clinical, economic, or humanistic outcomes of NSI or active safety-engineered devices.

Results

NSIs have been reported by 14.9%–69.4% of HCWs with the wide range due to differences in countries, settings, and methodologies used to determine rates. Exposure to contaminated sharps is responsible for 37%–39% of the worldwide cases of hepatitis B and C infections in HCWs. HCWs may experience serious emotional effects and mental health disorders after a NSI, resulting in work loss and post-traumatic stress disorder. In 2015 International US$ (IntUS$), the average cost of a NSI was IntUS$747 (range IntUS$199–1,691). Hypodermic injections, the most frequent cause of NSI, are responsible for 32%–36% of NSIs. The use of safety devices that cover the needle-tip after hypodermic injection lowers the risk of NSI per HCW by 43.4%–100% compared to conventional devices. The economic value of converting to safety injective devices shows net savings, favorable budget impact, and overall cost-effectiveness.

Conclusion

The clinical, economic, and humanistic burden is substantial for HCWs who experience a NSI. Safety-engineered devices for hypodermic injection demonstrate value by reducing NSI risk, and the associated direct and indirect costs, psychological stress on HCWs, and occupational blood-borne viral infection risk.

Introduction

Needlestick injury (NSI) is an accidental percutaneous piercing wound caused by a contaminated sharps instrument, usually a hollow-bore needle from a syringe, and is one of the most frequent routes of transmission in occupationally acquired blood-borne infections.Citation1 More than 20 blood-borne infections may be transmitted by NSI. In the most severe cases, the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) may severely impair quality of life and reduce life expectancy, while incurring substantial costs, especially in the long term.Citation2–Citation6

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of safety injection devices and instructs governments to transition to their exclusive use by 2020.Citation7 The USA, Canada, Brazil, Taiwan, United Kingdom (UK) and European Union (EU) countries have enacted legislation requiring the use of safety injection devices. Despite an increased awareness and legislation in some countries, NSIs and their serious consequences still occur. Since NSIs occur most often during hypodermic injections, this review sought to understand the burden of NSI by conducting a systematic literature review on NSI and active safety-engineered devices for hypodermic injection.

Methods

Literature searches were conducted in PubMed and EMBASE to identify outcomes – evidence of the burden of NSI and impact of safety needles with active mechanisms for hypodermic injection, as there are no currently marketed passive mechanism devices for hypodermic injection (Table S1). Search terms and combinations that were used in PubMed included needlestick injury, accidental needlestick, safety needles, safety-engineered needles, engineered sharps, needleless systems, needles, safety device, viral infections, quality of life, patient satisfaction, worry, distress, resource utilization, resource use, cost, budget impact, indirect cost, work loss, work policy, productivity, policy, public policy, and other related terms. Additional limits applied to each search included: humans, English language only, and publication date within past 10 years.

These searches identified 982 unique references. Inclusion criteria were studies that reported policy or clinical, economic, or humanistic outcomes of NSI or safety injection devices on healthcare workers (HCWs) in healthcare settings. Studies were defined as health economic or budget impact studies, real-world observational studies, comparative effectiveness studies, clinical trials, and case reports with an adequate sample size (n=20). Articles were excluded if the full text was not available, or if the article did not include hypodermic injections. Additional searches were conducted using Google and Google Scholar. In total, 155 references were selected after title/abstract screening, with 69 selected after full text review, and discussed in this review article.

Results

Legislation

As of 2017, several countries have enacted legislation regarding NSI and safety-engineered devices including the USA, CanadaCitation8, UK, EU countries,Citation9 Brazil,Citation10 and Taiwan.Citation11

The legislation has increased the use of safety-engineered devices, even in countries where these devices were available prior to the legislation. In the USA, voluntary adoption of safety devices without mandated legislation was ineffective in producing a large-scale reduction in NSI rates.Citation12 A significant 38% drop in hospital NSI rates occurred only after the Needlestick Safety Prevention Act (NSPA) was enacted and safety devices became the predominant technology in healthcare settings.Citation12,Citation13 Compliance with mandatory safety-engineered device legislation has been high in US hospital settings. However, HCWs in non-hospital settings (i.e., clinics, private offices, long-term care facilities, and free-standing laboratories) account for ~60% of the healthcare workforce, but have 25%–35% lower adoption rates of safety-engineered devices than hospitals.Citation13 In the UK, since the passage of the EU Council Directive 2010/32/EU and the Health and Safety (Sharps Instruments in Healthcare) Regulations of 2013, the majority of National Health Service (NHS) trusts instruct their staff to use safety devices whenever possible. However, one-third of the NHS trusts have failed to implement safe sharps practices.Citation14

Often, legislation without enforcement has less significant impact on the implementation of safety devices in health-care settings. In Brazil, adoption of safety devices has been slower as there are gaps in the monitoring of the adoption of safe practices, mainly related to preventing and controlling occupational accidents.Citation10

Clinical burden of NSIs

Rates of NSI in the hospital differ by country, use of safety devices, and methodologies (including potential under-reporting) used. Studies report a wide range from 14.9% to 69.4% of HCWs who have experienced a NSI, and 3.2–24.7 NSIs per 100 occupied hospital beds ().Citation15–Citation18

Table 1 Representative NSI rates by country

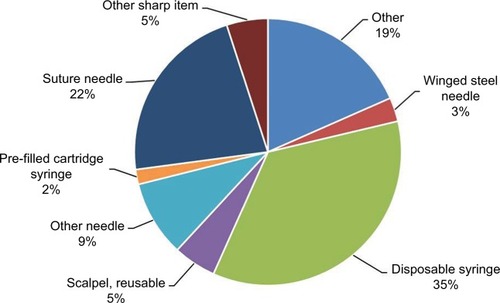

Hypodermic (i.e., intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intra-dermal) injections using disposable syringes and needles are the most frequent cause of NSIs worldwide.Citation18–Citation20 In US hospitals, 35.4% of all percutaneous injuries are due to disposable syringes (), with similar rates reported in other parts of the world – 32% in 13 European countries and Russia and 34.6% in Saudi Arabia.Citation18–Citation20

Figure 1 Frequency of NSIs by device, n=557.

Abbreviations: EPINet, exposure prevention information network; NSIs, needlestick injuries.

Literature that relies solely on officially reported NSIs may underestimate NSI rates. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that about half of sharps injuries in the US go unreported.Citation21 In Sweden, 26.9% of HCWs with a NSI in the preceding year did not report any or all of their NSI events, even though 80.1% of respondents knew to contact occupational health services.Citation22 There are multiple reasons that HCWs do not report NSIs: presumption that the risk of disease transmission is low, lack of knowledge of systems for reporting, lack of knowledge of the importance of reporting NSIs, complicated and unclear reporting protocols, and HCW belief that an injury may reflect poorly on their practice standards.Citation2,Citation23

NSI risk factors

NSIs appear to be repetitive, with 73% of HCWs who sustained a NSI noting a previous NSI.Citation24 Risk factors associated with NSIs have been categorized into two groups: modifiable and non-modifiable.Citation24,Citation25 Non-modifiable risk factors for NSI are conditions that cannot be deliberately altered. HCWs with the highest rates of NSIs are women, nurses, and those aged 21–30 years.Citation24,Citation25 The prevalence of these demographic characteristics is associated with higher rates of needle use as the majority of HCWs who handle syringes are female nurses.Citation24 Modifiable risk factors include hospital care setting, poor working environments such as long work hours, understaffing, and inadequate needle disposal procedures (e.g., 37% of HCWs recapped the needle) and devices (e.g., lack of sharps containers).Citation24,Citation26 Mental and physical stress associated with excessive working hours are also believed to contribute to a higher NSI rate.Citation24

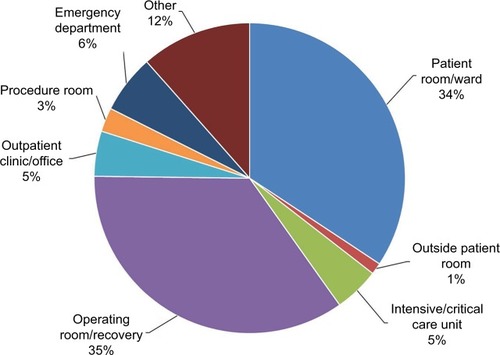

The most common hospital care settings for NSIs are the general medical wards, the operating room, the emergency department (ED), and the intensive and critical care units. In the US, 35% of sharps injuries occurred in the operating room, and 34.3% in patient rooms/wards ().Citation18 In Saudi Arabia, the highest rates of NSI occurred in the patient’s room (31.4%), followed by the ED (17.2%), then the intensive and critical care units (14.7%).Citation19

Figure 2 Work locations where reported sharps injuries occurred, n=592.

Abbreviation: EPINet, exposure prevention information network.

HCWs in urban EDs face higher risk for sharps injuries compared to community EDs with rates of 20.3 versus 5.9 per 100,000 patient visits, respectively (p<0.001).Citation27 The environment in EDs is fast-paced and often unpredictable, in addition to often unknown source status, thus increasing the risk of NSIs and their consequences.

In the intensive care units (ICUs), there is additional concern as patients may be incapacitated and unable to consent to testing should a NSI occur. This concern is highlighted in a study which found that 62.6% of ICUs in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland had reported one or more NSIs to an HCW from an incapacitated patient.Citation69 Of the 62 cases of NSIs, at least 25.8% of NSIs were from patients with blood-borne viruses, with 37.5% unaware of their positive status prior to ICU admission.

Infection risk from NSI

The risk of becoming infected with a blood-borne virus after NSI is highest for hepatitis B, followed by hepatitis C, and then HIV. For every 1,000 NSIs from an infected patient, 300 HCWs will become infected with HBV. For HCV and HIV, seroconversion rates are 30 per 1,000 and three per 1,000, respectively. Since the prevalence of blood-borne pathogens such as HBV, HCV and HIV is higher in hospitalized patients, there is greater risk after NSI in this setting.Citation29 Despite being unseen by the naked eye, blood remains on the needle after a hypodermic injection.Citation30 Exposure to even minute quantities of blood from a NSI can result in serious disease, with transmission linked to hypodermic injection noted in developing nations.Citation31

Safety devices reduce NSI rates

About 41% of NSIs from hollow-bore needles occur after the injection has been given: 19% occurring after use, but before disposal, and 22% occurring during, or after, disposal.Citation32 With disposable syringe/needle use, the process of recapping alone is responsible for 11.1% of injuries.Citation33 A systematic literature review on safety devices examined 17 articles, six of which included safety syringe/needle devices for hypodermic injection.Citation34 Compared to conventional devices, safety syringes/needles for hypodermic injection reduced the risk of NSIs by 43.4%–100%. A more recently published systematic review and meta-analysis found nine studies on safety syringe/needle devices for subcutaneous, intramuscular, and intradermal injections.Citation35 These hypodermic safety injection devices had a pooled relative risk of NSI of HCW of 0.54 (95% CI 0.41–0.71).

Active safety devices for hypodermic injection include a safety sliding shield needle, a safety toppling shield needle, and a safety pivoting shield needle. An active device (Septodont Safety Plus) reduced avoidable NSIs in a dental school practice from an average of 11.8 to 0 injuries per 1,000,000 hours worked per year as compared with a control unit who reduced their frequency from 26 to 20 injuries per 1,000,000 hours worked.Citation36 Studies in hospitals that reported the device name describe a one-handed, active manual activation device (BD SafetyGlide), activated by pushing a lever arm forward with a single finger stroke to cover needle tip, and a one-handed, active manual activation device (BD Eclipse) activated by pushing a hinged safety shield over the needle tip with a finger or thumb (). These studies found a significant reduction in NSIs of 64%–100%.Citation37–Citation39 In one of the studies, HCWs at a University Hospital in the UK completed questionnaires and noted that the BD SafetyGlide was “safe, usable and compatible with most clinical situations”, and felt that this safety needle device “should be used for any procedure where a risk of exposure to blood and body fluids existed”.Citation37

Table 2 Studies reporting rates of NSI after implementation of named active safety devices in hospitals

Another study compared NSI rates from different device types, without specifying device names.Citation70 Data from a French multicenter study reported the number (95% CI) of NSIs per 100,000 hypodermic injection devices purchased was 5.20 (4.61–5.78) and 2.94 (2.35–3.53) for manually activated protective sliding shield and manually activated protective toppling shield, respectively.Citation70

Economic burden

After a NSI occurs, there is substantial cost, which includes, 1) testing for infection in the injured worker and, if known, the patient on whom the needle/sharp had been used, 2) post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent or manage potential blood-borne virus transmission, 3) short- and long-term treatment of chronic blood-borne viral infections that are transmitted to injured workers, 4) staff absence and replacement, 5) counseling for injured workers, and 6) legal consequences (litigation and compensation claims).Citation23

summarizes the published economic studies reporting cost of a NSI, national burden, or economic impact of safety needle programs. These studies addressed a mix of direct and indirect costs, national burden, and economic impact of safety needles. Cost of a NSI varies widely and depends on what types of costs are included, as well as the risk/source of the needlestick. For example, the US CDC cites estimates of the direct costs associated with the initial followup and treatment of HCWs who sustain a NSI ranging from US$71 to US$5,000, depending on the treatment.Citation40 Some studies report that only some NSIs actually generated costs (e.g., 72.1% of NSIs in Korea), because of underreporting or cases with low-risk known sources.

Table 3 Economic analyses of the cost of a NSI and impact of safety devices

In studies reporting both direct and indirect costs, the cost breakdown of NSI ranged from 44% to 77% direct costs and 23% to 56% indirect costs.Citation3,Citation23,Citation41,Citation42 Within direct costs, the top cost driver is prophylaxis medications after the NSI, and ranges from 54% to 96% of the average direct medical costs after NSI. In Korean hospitals the NSI direct costs by department were 54.5% pharmacy, 29.7% laboratory tests, 11.7% medical services, and 4.2% medical treatments.Citation43

Economic benefits of safety injection needles

The current costs of safety needles are ~2–3 times the cost of non-safety needles. To gauge the impact of the use of safety needles on a hospital budget, studies have reported annual cost impact from a perspective important to healthcare administrators.Citation42 An Australian study found that the annual cost increase due to the use of hypodermic safety needles was the equivalent of $14 for each at-risk HCW or $2 per occupied bed per day.Citation42 Data from Spain show that the direct cost increase for hypodermic safety needles was €0.021 (US$0.028) per patient in the ED.Citation39

Although the acquisition costs of safety needles are greater than conventional needles, safety needles provide economic value based on the reduction in NSIs. In a Swedish study, direct medical costs resulting from 3,906 hollow-bore needle sharps injuries were found to be €0.04 (Swedish Krona [SEK] 0.34) per used needle.Citation44 Using safety devices instead of conventional needles at all hospitals, primary care facilities, and outpatient clinics outside hospitals was found to save €0.01 (SEK 0.07) per used needle for tests, investigations, and treatment. The assumption was that 80% of hollow-bore needle sharps injuries could be prevented, resulting in 3,125 fewer injuries. A review of the cost-effectiveness of safety devices in a study by Lee et al included data collected by California Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).Citation45 Due to the rising rates of NSI, the state of California analyzed the cost-effectiveness of using safety-engineered devices to support pending legislation that would require stricter handling of syringes. The California OSHA reported that the implementation of safety needle devices would cost the state $124 million. A cost savings of $228 million and $216 million would be realized with the elimination of new HIV and hepatitis cases, respectively. As a result, an annual savings of $320 million in healthcare costs was projected.Citation46 California OSHA found that the implementation of safety devices would produce savings much larger than the initial cost of using safety syringes.

In a dental school practice, the authors noted that the “reduction in cost of management of needlestick injuries including the psychological effects are significant” for hypodermic safety syringes.Citation36

In Belgium, an economic model found that the decrease in the long-term costs due to NSIs offsets the acquisition costs of safety needles.Citation23 A 5-year incidence-based budget impact model was developed from a 420-bed Belgian hospital inpatient perspective, comparing costs and outcomes with the use of safety devices and prior-used non-safety devices. The model included device acquisition costs and the costs of NSI management in blood collection, infusion, injection, and diabetes insulin administration. For injections, the average cost per conventional and safety injection device was €0.014 and €0.046, respectively, with an expected 86% reduction in NSI using safety injection devices. An increase in safety device acquisition costs was offset by savings through avoided NSIs. When switching to safety injection devices (including other safety devices beyond hypodermic injection), the net budget impact over 5 years showed a savings of €51,710. While a variety of sensitivity analyses and changes in model assumptions were performed, the results continued to demonstrate cost savings. The model was most sensitive to variation in the acquisition costs of safety devices, the rates of NSI associated with conventional devices, and the acquisition costs of conventional devices.Citation23

Avoiding financial penalties due to noncompliance with regulatory requirements

In the USA, OSHA enforces the requirements set forth by the NSPA. One of the requirements is that employers must consider and implement appropriate commercially available and effective safer medical devices designed to eliminate or minimize occupational exposure in healthcare settings where exposure is possible. The use of safety devices can assist with avoiding financial penalties (up to $12,675 per violation as of January 13, 2017Citation28) issued due to violations of the NSPA.

Humanistic burden

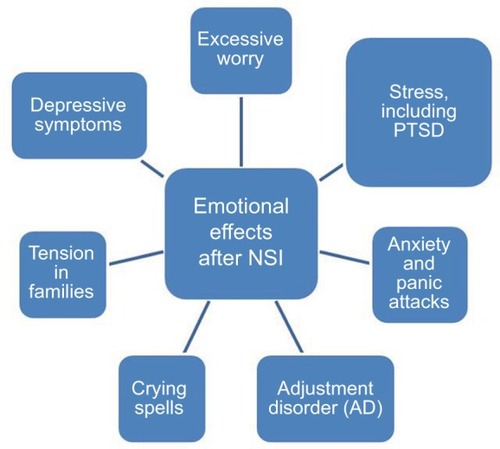

Nurses report that NSIs are the top concern for personal safety, followed by safety in the workplace.Citation47 In a survey administered through the American Nurses Association to over 700 nurses in the USA regarding NSIs and workplace safety climate, 64% of nurses say NSIs and blood-borne infections remain major concerns. After NSI, most HCWs report experiencing a range of psychological effects, as depicted in .Citation48,Citation49,Citation56 In a study of 313 HCWs post-NSI, 41.8% felt anxious, depressed, or stressed following the NSI.Citation71 In another study, anxiety was reported by 80.2% of HCWs post-NSI with 66.4% having mild/moderate anxiety, and 13.8% with persistent anxiety.Citation50 In hospital employees who were recently evaluated for blood/body fluid exposure (n=150), 53% reported feeling some anxiety that could be attributed to their recent exposure.Citation51

Figure 3 Humanistic impact of NSIs.

Abbreviations: NSIs, needlestick injuries; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Experiencing a NSI is significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (odds ratio 2.98), as found in a survey of medical students.Citation72 The study by Sohn et al provides the most thorough analysis of the effects of NSI on psychological outcomes.Citation53 In this study, psychological symptoms of 370 HCWs were assessed prior to and after NSI. The analysis showed that NSI was associated with a statistically significant increase in the Beck Depression Index (p<0.01).

In addition to depression and anxiety, HCWs exposed to NSI can experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and burnout.Citation52,Citation54,Citation55 After NSI, physicians had a statistically higher likelihood of PTSD (odds ratio of 4.28) based on the Impact of Event Scale questionnaire (IES-6).Citation54 In a study of 458 nurses, the Maslach Burnout Inventory questionnaire scores from nurses post-NSI indicated a statistically higher probability of burnout compared to unexposed nurses.Citation52

Longer-term humanistic impact exists when NSI is from a source with known HIV disease. Even after testing negative for almost 2 years after NSI, US nurses displayed symptoms consistent with PTSD, insomnia, ongoing depression and anxiety, nightmares, and panic attacks upon returning to the work environment where the injuries were received.Citation55

The humanistic impact and psychological effects of NSI are linked to lost productivity and work time in the USA and Europe.Citation41 In 110 US nurses reporting lost time from NSI, 77 days of work were missed, 10 due to seeking and receiving medical attention, six due to side effects from HIV prophylactic medication, and 61 due to emotional distress and anxiety following the NSI.Citation41 In Europe, nurses report changing their working habits/department 12.3% of time and stop working 2.4% of the time after NSI.Citation20

Gaps in the literature

Many studies describe the impact of safety-engineered devices on overall institutional NSI rates, but do not provide sufficient detail to determine the impact of specific type of safety device used. Safety-engineered devices for hypodermic injection reduce NSI risk, but quantification of reduced disease transmission for HIV, HBV and HCV is unknown. Calculations of the economic burden of NSI and the economic value of safety-engineered devices have typically lacked the inclusion of indirect cost components such as cost of transportation or the cost of fear/worry, changed behavior at work and at home and pain/suffering costs. These latter costs are difficult to estimate and while it is uncertain whether these costs would significantly change the total cost of NSIs, research needs to define their importance. In addition, most articles that assessed cost of NSI acknowledged that litigation costs due to a NSI may be significant. However, no article included costs of litigation or the incidence of legal action due to NSIs.

Conclusion

Although highly preventable with proper handling and equipment, NSIs are still a significant issue among HCWs globally despite legislation in many countries. Both direct and indirect costs of NSIs are high; however, healthcare institutions can achieve cost savings and cost offsets with implementation of safety needles and devices. In addition, small studies suggest a broad range of psychological domains that are impacted in HCWs with NSI, yet comprehensive assessments are lacking. Hypodermic injection is the most common cause of NSI. The economic and humanistic burden of NSI could be reduced by implementation of safety needles for hypodermic injection (which have reduced NSIs up to 100%), yet more must be done to enforce legislation. Future research is needed to better quantify the humanistic burden and long-term impacts of NSI for HCWs. In addition, economic studies are needed in country-specific healthcare settings to demonstrate the downstream cost offsets or cost savings of using safety needles and other safety devices for hypodermic injection.

Acknowledgments

Pharmerit International received funding from Becton Dickinson to conduct the research.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Search terms used in PubMed

Disclosure

CEC was a consultant to Pharmerit International during the research. JMS is an employee and stockholder of Pharmerit International.

References

- PhillipsEKConawayMRJaggerJCPercutaneous injuries before and after the Needlestick Safety and Prevention ActN Engl J Med2012336670671

- TruemanPTaylorMTwenaNChubbBThe cost of needlestick injuries associated with insulin administrationBr J Community Nurs200813941341719024036

- LeighJPGillenMFranksPCosts of needlestick injuries and subsequent hepatitis and HIV infectionCurr Med Res Opin20072392093210517655812

- SolemCTSnedecorSJKhachatryanACost of treatment in a US commercially insured, HIV-1-infected populationPLoS One201495e9815224866200

- PoonsapayaJMEinodshoferMKirkhamHSGloverPDuChaneJNew all oral therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV): a novel long-term cost comparisonCost Eff Resour Alloc2015131726445564

- LeeTAVeenstraDLHoejaUHSullivanSDCost of chronic hepatitus B infection in the United StatesJ Clin Gastroenterol20043810 Suppl 3S144S14715602162

- World Health OrganizationWHO Guideline On The Use of Safety-Engineered Syringes for Intramuscular, Intradermal and Subcutaneous Injections In Health-Care SettingsGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2015

- ChambersAMustardCAEtchesJTrends in needlestick injury incidence following regulatory change in Ontario, Canada (2004–2012): an observational studyBMC Health Serv Res20151512725880621

- WeberTPromotion and Support of Implementation Directive 2010/32/EU on the prevention of sharps injuries in the hospital and health care sector2013 Available from: https://osha.europa.eu/en/legislation/directives/council-directive-2010-32-eu-prevention-from-sharp-injuries-in-the-hospital-and-healthcare-sectorAccessed April 12, 2017

- Khalil SdaSKhalilOALopes-JuniorLCOccupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens in a specialized care service in BrazilAm J Infect Control2015438e39e4126234221

- WuHCHoJJLinMHChenCJGuoYLShiaoJSIncidence of percutaneous injury in Taiwan healthcare workersEpidemiol Infect2015143153308331525762054

- PhillipsEKConawayMParkerGPerryJJaggerJIssues in understanding the impact of the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act on hospital sharps injuriesInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201334993593923917907

- JaggerJPerryJGomaaAPhillipsEKThe impact of U.S. policies to protect healthcare workers from bloodborne pathogens: the critical role of safety-engineered devicesJ Infect Public Health200812627120701847

- MindMetreSafer sharps: a barometer of take-up in the UK2014 Available from: http://www.mindmetreresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/Safer-sharps_A-barometer-of-take-up-in-the-UK_report.pdfAccessed December 14, 2016

- NkokoLSpiegelJRauAYassiAReducing the risks to health care workers from blood and body fluid exposure in a small rural hospital in Thabo-Mofutsanyana, South AfricaWorkplace Health Saf201462938238825650472

- TalaatMKandeelAEl-ShoubaryWOccupational exposure to needlestick injuries and hepatitis B vaccination coverage among health care workers in EgyptAm J Infect Control200331846947414647109

- MemishZAAssiriAMEldalatonyMMHathoutHMBenchmarking of percutaneous injuries at the Ministry of Health hospitals of Saudi Arabia in comparison with the United States hospitals participating in Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet)Int J Occup Environ Med201561263325588223

- EPINetEPINet Report for Needlestick and Sharp Object InjuriesInternational Safety Center Available from: https://internationalsafetycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Official-2014-NeedleSummary.pdfAccessed April 12, 2017

- BalkhyHHEl BeltagyKEEl-SaedASallahMJaggerJBenchmarking of percutaneous injuries at a teaching tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia relative to United States hospitals participating in the Exposure Prevention Information NetworkAm J Infect Control201139756056521636172

- CostigliolaVFridALetondeurCStraussKNeedlestick injuries in European nurses in diabetesDiabetes Metab201238Suppl 1S9S1422305441

- The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)Stop Sticks Campaign Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/stopsticks/default.htmlAccessed April 12, 2017

- VoideCDarlingKEKenfak-FoguenaAErardVCavassiniMLazor-BlanchetCUnderreporting of needlestick and sharps injuries among healthcare workers in a Swiss University HospitalSwiss Med Wkly2012142w1352322328010

- HanmoreEMaclaineGGarinFAlonsoALeroyNRuffLEconomic benefits of safety-engineered sharp devices in Belgium - a budget impact modelBMC Health Serv Res20131348924274747

- AfridiAAKumarASayaniRNeedle stick injuries risk and preventive factors: a study among health care workers in tertiary care hospitals in PakistanGlob J Health Sci201354859223777725

- ChalyaPLSeniJMushiMFNeedle-stick injuries and splash exposures among health-care workers at a tertiary care hospital in north-western TanzaniaTanzan J Health Res2015172115

- GillenMMcNaryJLewisJSharps-related injuries in California healthcare facilities: pilot study results from the sharps injury surveillance registryInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol200324211312112602693

- WilsonSPMillerJMahanMKruppSThe Urban Emergency Department: a potential increased occupational hazard for sharps-related injuriesAcad Emerg Med201522111348135026468634

- Occupational Safety and Health AdministrationOSHA penalties as of January 13, 2017 Available from: https://www.osha.gov/penalties/Accessed August 21, 2017

- WittmannAHofmannFKraljNNeedle stick injuries - Risk from blood contact in dialysisJ Ren Care2007332707317702509

- NapoliVMMcGowanJEJrHow much blood is in a needlestick?J Infect Dis198715548283819482

- SimonsenLKaneALloydJZaffranMKaneMUnsafe injections in the developing world and transmission of bloodborne pathogens: a reviewBull World Health Organ1999771078980010593026

- The Centers for Disease Control and PreventionThe National Surveillance System for Healthcare Workers (NaSH): summary report for blood and body fluid exposure data collected from participating healthcare facilities (June 1995 through December 2007)2011 Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/nash/nash-report-6-2011.pdfAccessed April 12, 2017

- JaggerJBerguerRPhillipsEKParkerGGomaaAEIncrease in sharps injuries in surgical settings versus nonsurgical settings after passage of national needlestick legislationJ Am Coll Surg2010210449650220347743

- TumaSSepkowitzKAEfficacy of safety-engineered device implementation in the prevention of percutaneous injuries: a review of published studiesClin Infect Dis20064281159117016575737

- HarbACTarabayRDiabBBalloutRAKhamassiSAkiEASafety engineered injection devices for intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intra-dermal injections in healthcare delivery settings: a systematic review and meta-analysisBMC Nurs2015147126722224

- ZakrzewskaJMGreenwoodIJacksonJIntroducing safety syringes into a UK dental school a controlled studyBr Dent J20011902889211213339

- AdamsDElliottTSImpact of safety needle devices on occupationally acquired needlestick injuries: a four-year prospective studyJ Hosp Infect2006641505516822584

- van der MolenHFZwindermanKAHSluiterJKFrings-DresenMHWBetter effect of the use of a needle safety device in combination with an interactive workshop to prevent needle stick injuriesSafety Science2011498–911801186

- VallsVLozanoMSYánezRUse of safety devices and the prevention of percutaneous injuries among healthcare workersInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol200728121352136017994515

- The Centers for Disease Control and PreventionImplementing and evaluating a Sharps Injury Prevention Program2008 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/sharpssafety/pdf/sharpsworkbook_2008.pdfAccessed April 12, 2017

- LeeWCNicklassonLCobdenDChenEConwayDPashosCLShort-term economic impact associated with occupational needlestick injuries among acute care nursesCurr Med Res Opin200521121915192216368040

- WhitbyMMcLawsMLSlaterKNeedlestick injuries in a major teaching hospital: the worthwhile effect of hospital-wide replacement of conventional hollow-bore needlesAm J Infect Control200836318018618371513

- OhHSYoon ChangSWChoiJSParkESJinHYCosts of postexposure management of occupational sharps injuries in health care workers in the Republic of KoreaAm J Infect Control2013411616522704735

- GlenngardAHPerssonUCosts associated with sharps injuries in the Swedish health care setting and potential cost savings from needle-stick prevention devices with needle and syringeScand J Infect Dis200941429630219229763

- LeeJMBottemanMFXanthakosNNicklassonLNeedlestick injuries in the United States. Epidemiologic, economic, and quality of life issuesAAOHN J200553311713315789967

- California Occupational Safety and Health AdministrationBloodborne pathogens. 8. California Code of Regulations1998 Available from: https://www.dir.ca.gov/title8/5193.htmlAccessed April 12, 2017

- McNamaraMPattersonDWorkplace Safety And Needlestick Injuries Are Top Concerns For Nurses www.nursingworld.orgAmerican Nurses Association200814 Available from: http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/WorkplaceSafety/Healthy-Work-Environment/SafeNeedles/Press/WorkplaceSafetyTopConcerns.pdfAccessed April 12, 2017

- WrightDHepatitis C nightmare. Interview by Charlotte AldermanNurs Stand2005202627

- SeibertCStuckAnn Intern Med2003138976576612729434

- WickerSStirnAVRabenauHFvon GierkeLWutzlerSStephanCNeedlestick injuries: causes, preventability and psychological impactInfection201442354955224526576

- GershonRRFlanaganPAKarkashianCHealth care workers’ experience with postexposure management of bloodborne pathogen exposures: a pilot studyAm J Infect Control200028642142811114612

- WangSYaoLLiSLiuYWangHSunYSharps injuries and job burnout: a cross-sectional study among nurses in ChinaNurs Health Sci201214333233822690707

- SohnJWKimBGKimSHHanCMental health of healthcare workers who experience needlestick and sharps injuriesJ Occup Health200648647447917179640

- NaghaviSHShabestariOAlcoladoJPost-traumatic stress disorder in trainee doctors with previous needlestick injuriesOccup Med (Lond)201363426026523580567

- WorthingtonMGRossJJBergeronEKPosttraumatic stress disorder after occupational HIV exposure: two cases and a literature reviewInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol200627221521716465645

- GreenBGriffithsECPsychiatric consequences of needlestick injuryOccup Med (Lond)201363318318823430785

- The Australian Council on Healthcare StandardsInfection Control version 3.1. Retrospective Data In Full13th edSydney, NSWACHS2012

- MarzialeMHRochaFLRobazziMLCenziCMdos SantosHETrovoMEOrganizational influence on the occurrence of work accidents involving exposure to biological materialRev Lat Am Enfermagem201321Spec No19920623459908

- ZhangXGuYCuiMStallonesLXiangHNeedlestick and sharps injuries among nurses at a teaching hospital in ChinaWorkplace Health Saf201563521922526031696

- FloretNAli-BrandmeyerOL’HériteauFSharp decrease of reported occupational blood and body fluid exposures in French hospitals, 2003–2012: results of the French National Network Survey, AES-RAISINInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201536896396825896252

- StefanatiABoschettoPPreviatoSA survey on injuries among nurses and nursing students: a descriptive epidemiologic analysis between 2002 and 2012 at a University HospitalMed Lav20151063216229 Italian25951867

- FrijsteinGHortensiusJZaaijerHLNeedlestick injuries and infectious patients in a major academic medical centre from 2003 to 2010Neth J Med2011691046546822058270

- OhHSYiSEChoeKWEpidemiological characteristics of occupational blood exposures of healthcare workers in a university hospital in South Korea for 10 yearsJ Hosp Infect200560326927515949619

- ShiaoJSLinMSShihTSJaggerJChenCJNational incidence of percutaneous injury in Taiwan healthcare workersRes Nurs Health200831217217918196578

- Royal College of NursingNeedlestick injury in 2008 results from a survey of RCN members2008 Available from: https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-003304Accessed April 12, 2017

- Van der MolenHFZwindermanKASluiterJKFrings-DresenMHInterventions to prevent needle stick injuries among health care workersWork201241Suppl 11969197122317004

- MannocciADe CarliGDi BariVHow much do needlestick injuries cost? A systematic review of the economic evaluations of needlestick and sharps injuries among healthcare personnelInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201637663564627022671

- O’MalleyEMScottRD2ndGayleJCosts of management of occupational exposures to blood and body fluidsInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol200728777478217564978

- BurrowsLAPadkinAA survey of the management of needlestick injuries from incapacitated patients in intensive care unitsAnaesthesia201065988088421198483

- TosiniWCiottiCGoyerFLolomIL’HeŕiteauFAbiteboulDPellissierGBouvetENeedlestick injury rates according to different types of safety-engineered devices: results of a French multicenter studyInfect Control Hosp Epidemiol201031440240720175681

- LeeJMBottemanMFNicklassonLCobdenDPashosCLNeedlestick injury in acute care nurses caring for patients with diabetes mellitus: a retrospective studyCurr Med Res Opin200521574174715969873

- WadaKSakataYFujinoYThe association of needlestick injury with depressive symptoms among first-year medical residents in JapanInd Health200745675755