Abstract

Aim

To summarize the evidence on clinical effectiveness and safety of wearable cardioverter defibrillator (WCD) therapy for primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac arrest in patients at risk.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature search in databases including MEDLINE via OVID, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and CRD (DARE, NHS-EED, HTA). The evidence obtained was summarized according to GRADE methodology. A health technology assessment (HTA) was conducted using the HTA Core Model® for rapid relative effectiveness assessment. Primary outcomes for the clinical effectiveness domain were all-cause and disease-specific mortality. Outcomes for the safety domain were adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs). A focus group with cardiac disease patients was conducted to evaluate ethical, organizational, patient, social, and legal aspects of the WCD use.

Results

No randomized- or non-randomized controlled trials were identified. Non-comparative studies (n=5) reported AEs including skin rash/itching (6%), false alarms (14%), and palpitations/light-headedness/fainting (9%) and discontinuation due to comfort/lifestyle issues (16–22%), and SAEs including inappropriate shocks (0–2%), unsuccessful shocks (0–0.7%), and death (0–0.3%). The focus group results reported that experiencing a sense of security is crucial to patients and that the WCD is not considered an option for weeks or even months due to expected restrictions in living a “normal” life.

Conclusion

The WCD appears to be relatively safe for short-to-medium term, but the quality of existing evidence is very low. AEs and SAEs need to be more appropriately reported in order to further evaluate the safety of the device. High-quality comparative evidence and well-described disease groups are required to assess the effectiveness of the WCD and to determine which patient groups may benefit most from the intervention.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease patients most commonly die of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA). SCA causes approximately 25% of 17 million deaths of cardiovascular disease patients worldwide every year.Citation1 About 350,000 SCAs occur out of hospital each yearCitation2 in Europe. In the US, estimations suggest that 326,000 persons are affected by SCAs outside of the hospital on an annual basis, whereby a large part of these SCAs happen in the domestic environment with 50% of the cases unnoticed by others.Citation3 Predominantly, ventricular tachycardia (VT) and ventricular fibrillation (VF) constitute the main pathophysiological mechanisms of SCA.Citation1,Citation4 Untreated SCA results in sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) which can automatically intervene and terminate life-threatening arrhythmias are the current standard for prevention of SCD. Pharmacological treatment and/or catheter ablation were documented to decrease the risk of SCD in some subsets of cases. Immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation and the application of automated external defibrillators have shown improved survival from SCA.Citation1 The wearable cardioverter defibrillator (WCD) represents a new addition to the spectrum of strategies for the prevention of SCD.

Limited information on effectiveness and safety of the WCD in the form of health technology assessment (HTA) reports or recently published reviews is available.Citation5–Citation7 The American Heart Association (AHA) published a science advisory on the WCD in 2016, which includes recommendations on possible use of the WCD with the intention to offer clinicians some directions for discussing therapy options with patients. The authors highlighted that discussion of patient preferences is of utmost importance.Citation7 Furthermore, no information on possible ethical, organizational, patient, social, and legal aspects of the WCD use is available, which is also pointed out in a recent paper by Reek et al.Citation8 Recently, the European Network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA) introduced the Core Model® for rapid relative effectiveness assessment (REA) – a methodological framework for the assessment of clinical effectiveness and safety of pharmaceuticals, diagnostic technologies, medical and surgical interventions, and screening technologies. This model was used to evaluate clinical effectiveness and safety of the WCD therapy for primary and secondary prevention of SCA in patients over 18 years of age (under CE mark) and children (outside of CE mark) at risk. In addition, the focus group study strived to evaluate perspectives of patients on areas of their cardiac disease and on the WCD therapy. Furthermore, it aimed to detect possible neglected outcomes. Both the assessment and the focus group study intended to provide information on relevant aspects of the WCD use.

Methods

Systematic literature search, study selection, and internal validity

We conducted a comprehensive systematic literature search on July 14, 2016 in MEDLINE via OVID, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and CRD (DARE, NHS-EED, HTA) databases, without any restriction on timeframe or study design, which we complemented by a “Scopus search” (ie, citation tracking of three recent key publications of the WCD) and by hand search. We assessed registries of clinical trials to identify registered ongoing clinical trials and observational studies: ClinicalTrials.gov and International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. Furthermore, we performed a distinct guideline search (G-I-N, National Guidelines Clearinghouse, TRIP-Database, and hand search).

We applied inclusion criteria for the literature selection that were defined using the Population-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome-(Study design) model shown in . No minimum number of participants in a study was applied as an inclusion criterion. However, individual case reports were excluded. Furthermore, we did not consider studies discussing induced VT/VF in hospitals. Two researchers autonomously selected references for inclusion and assessed the internal validity of studies. In case of differences in the results, agreement was reached by discussion. A third researcher was contacted in case of disagreements. In order to assess the risk of bias of included prospective studies without a control group, the quality appraisal tool for case series was applied.Citation9

Table 1 Inclusion criteria for selecting the literature according to the Population-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome-(Study design) model

Data extraction and management

One researcher performed the extraction of data. The second researcher autonomously examined whether the data are correct and complete. A third researcher was contacted in case of disagreements, and differences were settled by discussion.

Outcome measures

Outcomes were selected according to the recommendations from pertinent clinical guidelinesCitation1,Citation10 and were compliant with the EUnetHTA guidelines,Citation11,Citation12 which state that rapid REAs should be based whenever possible on final clinical end points relevant for patients (which mainly fall under the categories of mortality, morbidity, health-related quality of life [HRQoL]) and not surrogate end points. Furthermore, outcomes were discussed among the assessment team in consultation with a clinical cardiologist. Primary outcomes for the clinical effectiveness domain were all-cause mortality and disease-specific mortality (ie, prevention of SCA). Secondary outcomes were incidence of VT or VF, appropriate shocks and withheld shocks (use of response button for delaying therapy), first shock success, improvement of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), avoidance of ICD implantation, HRQoL, hospitalization rate, satisfaction with the WCD, and patient compliance with the technology (WCD wear time, WCD daily use). For the safety domain, the outcomes were adverse events (AEs), frequency of discontinuation due to AEs, frequency of unexpected AEs, serious adverse events (SAEs), and frequency of SAEs leading to death.

Synthesis of evidence

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation – GRADE methodology – was used to summarize and evaluate the strength of the evidence.Citation13 A classification (critical; important, but not critical; of limited importance) of the importance of the outcomes was performed. Only the outcomes that were considered critical were the primary factors influencing the conclusion. It was not possible to perform a meta-analysis because no prospective controlled studies were identified.

Other data sources and respective quality assessment

The manufacturer ZOLL Medical Corporation (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) was contacted on May 10, 2016 and asked to complete the EUnetHTA medical devices evidence submission file template, which mainly included questions on the WCD and its current use. The revised completed document was received on July 26, 2016. (ZOLL Medical Corporation, unpublished data, 2016). Relevant literature from the literature search and information from the submission file were used for the background. For ethical, organizational, patient, social, and legal questions, appropriate literature from the search was applied and complemented by a hand search for qualitative studies. No quality assessment tool was applied for these parts, but the use of several sources served in validation of individual, maybe biased, sources. After critical appraisal of these distinct information sources, their content was described.

Methodological framework

The present analysis was performed as the EUnetHTA collaborative assessment/HTACitation14 based on the EUnetHTA Core Model®, which is a methodological framework for the production and sharing of HTA information. It includes generic questions that are translated into actual research questions. In this context, the application for REA (version 4.2)Citation15 including some additional questions from the ethical, organizational, patient, social, and legal domains of the EUnetHTA Core Model® (version 3.0),Citation16 relevant for medical and surgical interventions, was used.

Reporting

This analysis was reported based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.Citation17

Patient involvement – focus group study

The focus group represents a qualitative research method where a small group of participants discuss a topic guided by a moderator. It was selected as the most appropriate qualitative research method for involvement of patients in this context. It was the first time that patients were involved by means of a focus group study in an HTA by the EUnetHTA. A standardized e-mail reached members of the nine regional associations of the Austrian organization for heart and lung transplant patients aiming to find eligible patients/volunteers for the focus group. The aim was to include a small sample of patients who would have (had) an indication for the WCD. Semi-structured interview questions were developed by the assessment team and were based upon a hand search of patient involvement websites, such as the Scottish Medicine Consortium and its PACE process, and a review of appropriate literature.Citation18,Citation19 A set of questions was divided into three parts. The first part consists of engagement questions, the second part contains exploration questions, and the third part exit questions (). The four-hour meeting that was held in German was chaired by a patient support expert, who also assisted in finding and preparing volunteers for the focus group. The participants agreed that the meeting could be recorded. The anonymized transcript was analyzed based on framework analysis.Citation18 Extraction of patient-relevant end points (clustering/charting), including main statements relevant for ethical, organizational, patient, social, legal, or other aspects of WCD use, was done by one researcher and checked by the second. Participants needed to provide informed consent as well as confirm that they had no conflict of interest and received remuneration. The Austrian Ethics Committee did not request an ethical approval with reference to section 15a, subsection 3a, of the Viennese Law on health institutions.

Table 2 Semi-structured interview questions of the focus group study

Results

Search results

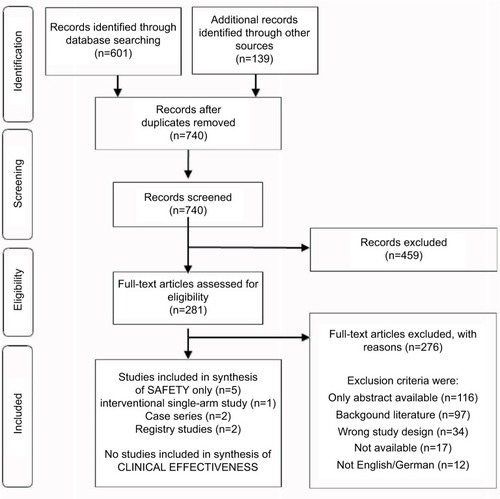

The systematic literature search yielded 601 references, and further 139 citations were identified through other sources (). According to our selection criteria, no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or non-randomized controlled trials assessing the clinical effectiveness of the WCD were found. For the assessment of safety, one prospective interventional single-arm study,Citation20 two prospective case series,Citation21,Citation22 and two prospective registry studiesCitation23,Citation24 fulfilled our inclusion criteria.

Figure 1 Flow chart of the selection process according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.Citation17

Study and patient characteristics

Study characteristics

The study inclusion criteria for the assessment of clinical effectiveness of the WCD were not met by any study.

A total of five non-comparative studies were included in the assessment of safety of the WCD: the prospective interventional single-arm studyCitation20 included 289 patients, two prospective case series included a total of 36 patients,Citation21,Citation22 and two prospective registry studies included a total of 2089 patientsCitation23,Citation24 ().

Table 3 Results from prospective non-comparative studies – study/patient characteristics and safety outcomes

Patient characteristics

Patient inclusion criteria within the included studies demonstrated some heterogeneity regarding LVEF (<30%,Citation20 ≤40%,Citation23 the other included studies did not report on this outcome) and in terms of the nature of heart disease (newly diagnosed peripartum cardiomyopathy,Citation21 early post-myocardial infarction (MI)/MI phase,Citation22 combination of several heart disease groupsCitation20,Citation23,Citation24). However, all patients were considered to be at high risk of SCA. Only two studies indicated having an active ICD and being unable to use the WCD because of impairment as exclusion criteria for study participants.Citation20,Citation23 Three out of five studiesCitation20,Citation21,Citation23 reported on previous patient treatments ().

Effectiveness

No RCTs or non-randomized controlled trials were found to assess the clinical effectiveness of the WCD.

Safety

Comparative studies

Since no study with a control group was identified, no assessment of relative safety of the WCD could be performed.

Non-comparative studies

Not all the included non-comparative studies reported on the different AEs and SAEs (). The following AEs were identified: skin rash and itching (in 6% of patientsCitation20), false alarms (in 14% of patientsCitation21), and palpitations, light-headedness, and fainting (in 9% of patientsCitation23); discontinuation due to comfort and lifestyle issues (in 22%Citation20 and 16% of patients,Citation23 respectively) was also reported. Unexpected AEs were not indicated in any of the included studies. SAEs mentioned were inappropriate shocks and unsuccessful shocks. The definition of inappropriate WCD therapy referred to non-VT/VF episodes detected and treated by a WCD shock.Citation24 Two studies indicated that 2%Citation20 and 0.5%Citation24 of patients respectively were affected by inappropriate shocks. The other three studies indicated no inappropriate shocks. Four out of five studies mentioned unsuccessful shocks. In one study, 0.7% of patientsCitation20 experienced unsuccessful shocks because the therapy electrodes were placed incorrectly. Unsuccessful shocksCitation21,Citation22,Citation24 were indicated in three studies and not reported in one study. All five studies indicated the frequency of SAEs leading to death, where death occurred in one study (0.3%)Citation20 (). However, with reference to the GRADE methodology, the quality of the body of evidence of the studies included for the assessment of safety was very low ().

Table 4 Quality of the body of evidence of the studies included for the assessment of safety according to GRADE methodologyCitation13

Focus group results

Ten eligible patients (nine men and one woman) responded to the standardized email, among which five men, who were 55–73 years old (mean age 65 years) from Austria and Germany, were able to participate. All respondents had experienced heart transplantation, and four had received the ICD before. Patients who would have qualified for the WCD prior to their heart transplantation explained their disease history, and no one had experiences with using the WCD or had any knowledge regarding this technology. Only men volunteered for the focus group; therefore, no issues regarding gender could be assessed. Furthermore, the majority of patients were exercising competitive sports. Main results are summarized in .

Table 5 Main results from the focus group study

Discussion

No RCTs or non-randomized controlled studies were found to assess the clinical effectiveness of the WCD; therefore, strong evidence on patient benefit is missing. Since no comparative studies were available, assessment of relative safety of the WCD could not be performed. Results from five non-comparative studies comprising 2414 patients undergoing WCD therapy propose that the WCD might be a relatively safe intervention for a short-to-medium period of time, but the quality of the body of evidence was very low. The patients’ focus group study was successfully implemented, providing the data on ethical, organizational, patient, social, and legal aspects of the WCD use; for example, reservations of patients toward the WCD were identified.

At present, just one WCD, namely the LifeVest® produced by ZOLL Medical Corporation, is available. The patient needs to wear the WCD all day and night long, except while taking a bath or shower.Citation25 The vest is worn around the chest of the patient and includes electrodes. The monitor is attached around the waist or carried using shoulder strap. The heart of the patient is permanently monitored, and in the event of a life-threatening heart rhythm like VT or VF that can be treated by the WCD, an automatic treatment shock is triggered. The conscious patient can press two response buttons on the monitor anytime during the treatment sequence in order to delay therapy. In Europe, the LifeVest® was granted CE mark for its first-generation model, WCD 1, in 1999, and for the latest fifth generation, WCD 4000, in 2011. The indication for the LifeVest® refers primarily to patients 18 years of age and older who are at risk of SCA and are not candidates for or refuse an ICD (ZOLL Medical Corporation, unpublished data, 2016). In the US, the LifeVest® was granted initial FDA approval in 2001; in 2015, it was also approved for children who are at risk of SCA, but are not candidates for an ICD because of certain medical conditions or in case the parents did not give their consent.Citation26 To date, the WCD does not include pacing capabilities for backup bradycardia pacing or anti-tachycardia overdrive pacing.Citation25,Citation27 Therefore, particularly patients for whom ICDs are a comparator are left unprotected, because recent models of ICDs provide these functions.Citation28 The WCD claims to temporarily protect from SCD in phases of enhanced risk during diagnosis or an event of post-VT/VF and the adequate therapy or its optimization.

Regarding safety of the WCD, AEs were not systematically reported in the included studies. The registry study including the highest number of participants (2000 patients) only outlined SAEs.Citation24 Each one of the three smaller studies described distinct AEs: skin rash/itching, false alarms, and palpitations, light-headedness, and fainting.Citation20,Citation21,Citation23 According to the literature, allergic contact dermatitis could be induced by metal hypersensitivity during the WCD use.Citation29 Compliance with the WCD use might also be linked to climate: patients tend to wear it less during the summer season,Citation30 which could also be associated with skin-related AEs. Three out of five included studies indicated earlier treatments,Citation20,Citation21,Citation23 whereas none of the included studies outlined whether the patients received treatment in the course of the WCD use, which could have had an impact on part of the outcomes (ie, pharmacological therapy could result in side effects). AEs and SAEs stated were of importance to patients, but since there was a lack of reporting, this list might not be complete. Discontinuation due to comfort and lifestyle issues could be initiated by different causes: it is required to wear the WCD 24/7 that influences everyday life including routine. The focus group showed that patients might not want to wear the WCD in public, which further shows that user-dependent harms (such as unsuccessful shocks because of not having placed the therapy electrodes correctly,Citation20 use of the response button without indication, and averting a treatment that could potentially save a life) could be connected to compliance and personal attitude. The WCD needs to be fitted to each patient; however, it could occur that some patients have difficulties in wearing it because of their body shape;Citation31 that is, it could be an issue especially for women.

Results regarding unsuccessful shocks (in 0–0.7% of patients), inappropriate shocks (in 0–2% of patients), and frequency of SAEs leading to death (in 0–0.3% of patients) are homogenous. Further safety concerns could be bystander intervention and unsuccessful shocks due to signal interruption when the body falls and wedges.Citation32 Inappropriate shocks could differ in the subgroups as well. The risk of motion-related sensory artifacts is enhanced in WCDs (compared to ICDs) because they are applied externally.Citation27 Noise detected externally might also result in inappropriate shocks.Citation31 The WCD could also possibly not be compatible with unipolar pacing devices.Citation33 Furthermore, inappropriate WCD shocks have the potential to induce VF since they might not be synchronized in a correct way.Citation34

The eventual autonomy and freedom gained in living a normal life through moving in the out-of-hospital setting needs to be balanced against the patient’s responsibility of having to decide between appropriate and inappropriate shocks. The focus group study stated that they would not want to decide whether to use the WCD’s response button or not. The patients indicated that they would be afraid of possibly preventing an appropriate therapy and that they lack the knowledge and the decision-making competence that clinicians possess, which is in line with previous research.Citation35 Additionally, the autonomy is given at the expense of false security since the patients might understand that they are protected from all lethal arrhythmias and not just from VT and VF. The focus group also raised concerns about the WCD’s lack of pacing capabilities.

The principles of beneficence and non-maleficence have to be weighted. Uncertainties regarding the benefits of the WCD need to be discussed in contrast to the psychological benefit, that is, to feel secure and the opportunity for patients to remain in their normal surroundings. These highly subjective advantages need to be balanced with harms of which some might induce further arrhythmias that potentially result in death – contributing to psychological stress and fear/anxiety of technical failures.Citation36,Citation37 The focus group highlighted that experiencing a sense of security is crucial to them. They expected to be able to exercise, that is, to be athletes and to live with few restrictions despite receiving a therapy – which was the case when using the ICD. In addition, since relatives and/or caregivers should be around whenever the patient removes the garmentCitation25 and need to react after the WCD intervention, as the patient needs medical treatment post-shock,Citation27 they may also be susceptible to a psychological harm caused by the fear or anxiety. The WCD therapy was not considered an option for weeks or even months by the focus group due to expected restrictions because of efforts of wearing it and possible issues with its weight. They were afraid of being permanently reminded of their disease by wearing the defibrillator on the outside instead of having it implanted.

Against the backdrop of the limited knowledge on the appropriate patient group for the device and because of the large indication group and an uncertain or marginal benefit, the question regarding the principle of distributional justice of investing resources in devices of unproven benefit while not investing the resources elsewhere needs to be posed. Furthermore, the costs of the WCD as recognized by physicians as well as the question of cost-effectiveness of the WCD for a quality-adjusted life year and cost-effectiveness thresholds of different countries might lead to difficulties in accessing the WCD.Citation38,Citation39 Due to the lack of effectiveness data, assumptions regarding the WCD’s cost-effectiveness are calculated referring to the marginal effect of the WCD in the included studies with higher number of participants (<2%) and the published cost-effectiveness analyses as referenced above.

The WCD invades the sphere of privacy through collecting data regarding heart functions of the patient and through submitting it to the particular cardiologists (ZOLL Medical Corporation, unpublished data, 2016). However, this manipulation of personal data could be justified in case the benefit of the WCD is confirmed.

A number of limitations need to be considered when reviewing the present results. The main limitation of this analysis is connected with the absence of high-quality data on clinical effectiveness as well as with the limited number and quality of studies included in the assessment of safety. Four of the five included studies were characterized by high risk of bias, and the fifth study to very high risk of bias.Citation22 The limitations of the methodology were the following: study participants were not recruited consecutively,Citation20,Citation23,Citation24 it is uncertain whether participants entered the study at a similar point in the disease statusCitation20,Citation24 (or not meeting this criteriaCitation23), conflicts of interest or sources of funding for the study were not reported,Citation20,Citation22 and there was high loss to follow-up.Citation20 Four studies received funding from the manufacturer ZOLL Medical Corporation, and the fifth study did not clearly indicate possible funding.Citation22 Selection bias can especially occur in case series because patients are recruited from a specific population, that is, the hospital, which may not represent the general population appropriately (eg, multimorbidity, noncompliant personality traits). Because of the absence of comparators exposed to the same variables, effects shown could be a result of intervening effects (eg, in case of skin rash). The existing studies did not include the following relevant information: device model, settings of the monitor, number of response button use, number of false alarms, possible device–device interactions, information whether ICDs were indicated at the start of the WCD use and potentially could be avoided post-WCD use, and data on disease status (stage of disease) at baseline. Information on HRQoL and satisfaction with the WCD needs to be gathered using a standardized approach. Information on hospitalization would be of interest. Challenges regarding the focus group included the identification of participants representative for this patient group and the complexity of patient histories.

The AHA presented the WCD as a treatment option for VT and VF.Citation7 Further, the WCD is seen as an option for primary prevention (in patients post-MI or post-explantation of an ICD when immediate reimplantation is not possible) and for secondary prevention (in patients with a history of SCA or sustained VT and VF, in whom ICD is ineffective). Further clarification and definition of the WCD’s role in treatment and prevention are needed.

It must be highlighted that there remain several opacities with regard to the WCD use. A clear definition of the target population for the WCD is required. The possibility of an overuse of the WCD is caused by the fear behind the risk of SCD. Therefore, more dataCitation40 on risk stratification of patients at high risk is needed. These data might be available, but until now have been just shown as part of larger subgroups. That produces skewed results and offers the WCD as the treatment option for the whole subgroup, although it is most needed for high-risk patient groups. One example is a studyCitation24 where former SCA and syncope patients at highest risk are included in the general subgroup of nonischemic cardiomyopathy (NICM). This study showed that patients with ischemic and congenital/inherited heart disease revealed significantly enhanced probabilities of sustained VT/VF than those with NICM.Citation24 In a retrospective study, none of the 254 NICM patients received an appropriate WCD shock.Citation41 Furthermore, appropriate shocks in the included studies varied between 1.1 and 8%Citation20,Citation22,Citation24 up to 43%,Citation21 although one registry study left this outcome unreported.Citation23 The WCD was shown to have limited preventive impact; maximum of 2% of patients who used the LifeVest® experienced appropriate shocks in nearly any cohort (in total >8500 patients).Citation31 More data on the use of WCD in individual patient populations are needed to better define highest risk groups.

A proper definition of risk factors for SCA is still outstanding and that further exacerbates the choice of appropriate indications for the WCD. Different baseline risks of patients need to be assessed, which could be done by conducting an individual patient data analysis. In addition, data on the management of patients who did not respond to the first-line therapy of SCA are lacking.

Previous reviews included different study designs for the assessment of clinical effectiveness and safety of the WCD. However, only the inclusion of prospective evidence can provide robust data, and therefore, the present HTA excluded retrospective studies. In 2014, the Haute Autorité de Santé in France published an HTA, which includes prospective and retrospective studies and provides a reimbursement recommendation for a selected number of indications: ICD explantation, awaiting cardiac transplant, and post-MI with low ejection fraction.Citation5 The Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association in the US published a report in 2010,Citation6 in which the authors include two studies regarding the WCD;Citation20,Citation42 the remainder of studies are referring to controlled trials of ICDs. The authors summarized that the two studies focused on detecting and aborting VT/VF, not on evaluating the WCD’s effect since no direct evidence in controlled trials was available to assess its efficacy in relation to comparators like usual treatments or alternatives, which is consistent with our results.

Conclusion

Since no prospective comparative studies on the use of the WCD are available, neither the assessment of clinical effectiveness nor the comparative assessment of safety with the standard treatments can be made. Non-comparative data indicate that the WCD might be a relatively safe intervention for a short-to-medium period of time, but the quality of available evidence is very low. AEs and SAEs need to be more appropriately reported in order to further evaluate the safety of the device. The literature search and the focus group yield important insights into patient-relevant outcomes and ethical, organizational, patient, social, and legal aspects of the WCD use, which should be taken into account when therapy options are discussed between clinicians and patients. More high-quality comparative data are needed on efficacy and safety of WCDs in order to determine the patient groups that would derive highest benefit from the intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). The collaboration with clinical societies, such as the ESC, is highly appreciated to ensure latest professional expertise in the field, to spread, and to disseminate the results. The authors thank Dr. Josef Kautzner for his comments on a draft version of the manuscript. The authors thank Prof. Dr. Diana Delić-Brkljačić and Dr. Olaf Weingart for serving as external experts in the EUnetHTA rapid REA of the WCD. Furthermore, the authors are grateful to Dr. Leonor Varela Lema, Janet Puñal Riobóo, Dr. Sebastian Grümer, and Dr. Stefan Sauerland for the review of the draft EUnetHTA rapid REA report. This work was supported by the European Commission in the framework of the 3rd EU Health Program, which funded the EUnetHTA Joint Action 3 (Grant Agreement No. 724130). Sole responsibility for its contents lies with the author(s), and neither the EUnetHTA nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Since 2006, the EUnetHTA projects aim at sustainably stimulating European collaboration and international information transfer in the field of HTA: in one EU project (EUnetHTA 2006–2008) and 2 Joint Actions (Joint Action 1 2010–2012 and Joint Action 2 2012–2015) involving around 70 HTA organizations from the EU and EFTA countries, processes and tools to reduce redundancies in EU-wide HTA production were developed. In Joint Action 3 (2016–2020), the aim is to support optional collaboration at scientific and technical level between HTA bodies to validate the model for joint work which should be continued after the Joint Action 3.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PrioriSGBlomström-LundqvistCMazzantiA2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: the Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC)Eur Heart J201536412793286726320108

- APA-OTSÄrztekammer: Höhere Überlebensraten bei Herzstillstand sind machbar [Austrian Medical Chamber: higher survival rates in cardiac arrest patients are feasible]2013 Available from: http://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20131015_OTS0124/aerztekammer-hoehere-ueberlebensraten-bei-herzstillstand-sind-machbarAccessed September 29, 2016 German

- MozaffarianDBenjaminEJGoASAmerican Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics SubcommitteeHeart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart AssociationCirculation20151314e29e32225520374

- MyerburgRJJuntillaMJSudden cardiac death caused by coronary heart diseaseCirculation201212581043105222371442

- Haute Autorité de SantéLifeVest 4000St DenisHaute Autorité de Santé2014

- BlueCross Blue Shield Association (BCBSA) Technology Evaluation Center (TEC)Wearable Cardioverter-Defibrillator as a Bridge to Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator TreatmentChicago, ILBlue Cross Blue Shield Association (BCBSA)2010

- PicciniJPSrAllenLAKudenchukPJPageRLPatelMRTurakhiaMPAmerican Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke NursingWearable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy for the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a science advisory from the American Heart AssociationCirculation2016133171715172727022063

- ReekSBurriHRobertsPREHRA Scientific Documents Committee (as external reviewers)The wearable cardioverter-defibrillator: current technology and evolving indicationsEuropace201719333534527702851

- MogaCGuoBSchopflocherDHarstallCDevelopment of a Quality Appraisal Tool for Case Series Studies Using a Modified Delphi TechniqueEdmonton, ABInstitute of Health Economics2012

- KleinHUGoldenbergIMossAJRisk stratification for implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy: the role of the wearable cardioverter-defibrillatorEur Heart J201334292230224223729691

- European Network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA)Endpoints used in relative effectiveness assessment: surrogate endpoints2015 Available from: http://www.eunethta.eu/outputs/endpoints-used-relative-effectiveness-assessment-surrogate-endpoints-amended-ja1-guideline-fAccessed June 6, 2016

- European Network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA)EUnetHTA guidelines2015 Available from: http://www.eunethta.eu/eunethta-guidelinesAccessed June 6, 2016

- BalshemHHelfandMSchünemannHJGRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidenceJ Clin Epidemiol201164440140621208779

- EttingerSStanakMHuicMWearable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac arrest in patients at riskRapid assessment on other health technologies using the HTA Core Model for Rapid Relative Effectiveness AssessmentEUnetHTA Project ID: OTCA012016 Available from: http://www.eunethta.eu/outputs/1st-collaborative-assessment-wearable-cardioverter-defibrillator-wcd-therapy-primary-and-secAccessed January 31, 2017

- European Network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA)Rapid relative effectiveness assessments (4.2)2016 Available from: http://meka.thl.fi/htacore/ViewApplication.aspx?id=25468Accessed June 6, 2016

- European Network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA)HTA Core Model2016 Available from: http://meka.thl.fi/htacore/BrowseModel.aspxAccessed June 6, 2016

- HigginsJPTGreenSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [Updated March 2011]LondonThe Cochrane Collaboration2011

- DurandMAChantlerTPrinciples of Social ResearchLondonOpen University Press2014

- FriedAWildCBeteiligung von BürgerInnen und PatientInnen in HTA Prozessen. Internationale Erfahrungen und Good Practice Beispiele [Participation of Citizens and Patients in HTA Processes. International Experience and Good Practice Examples]WienLudwig Boltzmann Institut für Health Technology Assessment2016 German

- FeldmanAMKleinHTchouPWEARIT investigators and coordinatorsBIROAD investigators and coordinatorsUse of a wearable defibrillator in terminating tachyarrhythmias in patients at high risk for sudden death: results of the WEARIT/BIROAD.[Erratum appears in Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004 May;27(5):following table of contents]Pacing Clin Electrophysiol20042714914720148

- DunckerDHaghikiaAKönigTRisk for ventricular fibrillation in peripartum cardiomyopathy with severely reduced left ventricular function-value of the wearable cardioverter/defibrillatorEur J Heart Fail201416121331133625371320

- KondoYLinhartMAndriéRPSchwabJOUsefulness of the wearable cardioverter defibrillator in patients in the early post-myocardial infarction phase with high risk of sudden cardiac death: a single-center European experienceJ Arrhythm201531529329526550085

- KaoACKrauseSWHandaRWearable defibrillator use In heart Failure (WIF) InvestigatorsWearable defibrillator use in heart failure (WIF): results of a prospective registryBMC Cardiovasc Disord20121212323234574

- KutyifaVMossAJKleinHUse of the wearable cardioverter defibrillator in high-risk cardiac patients: data from the Prospective Registry of Patients Using the Wearable Cardioverter Defibrillator (WEARIT-II Registry)Circulation2015132171613161926316618

- ChungMKThe role of the wearable cardioverter defibrillator in clinical practiceCardiol Clin201432225327024793801

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)FDA approves wearable defibrillator for children at risk for sudden cardiac arrest2015 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm466852.htmAccessed April 14, 2016

- AdlerAHalkinAViskinSWearable cardioverter-defibrillatorsCirculation2013127785486023429896

- GanzLIGeneral principles of the implantable cardioverter-defibrillatorUptodate2016 Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/general-principles-of-the-implantable-cardioverter-defibrillatorAccessed October 5, 2016

- GarnerAMAnejaSJahan-TighRRAllergic dermatitis from a defibrillator vestDermatitis2016273151

- CroninEMBiancoNRChungRAbstract 14183: some like it cool-seasonal temperature, as well as clinical and demographic factors, predicts compliance with the wearable cardioverter defibrillatorCirculation2011124Suppl 21A14183

- ChungMKWearable cardioverter-defibrillatorPageRLDowneyBCUpToDateWaltham, MAUpToDate2016

- ChungMKSzymkiewiczSJShaoMNiebauerMJLindsayBDTchouPJAggregate national experience with the wearable cardioverter-defibrillator vest: event rates, compliance and survivalJ Am Coll Cardiol20105510A10.E98

- LaPageMJCanterCERheeEKA fatal device-device interaction between a wearable automated defibrillator and a unipolar ventricular pacemakerPacing Clin Electrophysiol200831791291518684292

- FrancisJReekSWearable cardioverter defibrillator: a life vest till the life boat (ICD) arrivesIndian Heart J2014661687224581099

- GawandeAComplications: A Surgeon’s Notes on a Imperfect ScienceNew YorkPicador2002

- LenarczykRPotparaTSHaugaaKHHernández-MadridASciaraffiaEDagresNScientific Initiatives Committee, European Heart Rhythm AssociationThe use of wearable cardioverter-defibrillators in Europe: results of the European Heart Rhythm Association surveyEuropace201618114615026842735

- KetilsdottirAAlbertsdottirHRAkadottirSHGunnarsdottirTJJonsdottirHThe experience of sudden cardiac arrest: becoming reawakened to lifeEur J Cardiovasc Nurs201413542943524013168

- La PageMJSaltzmanGMSchumacherKRCost effectiveness of the wearable automated defibrillator for primary prevention in pediatric heart transplant candidatesJ Card Fail2013198S64

- KondoYKuritaTUedaMEfficacy and cost-effectiveness of wearable cardioverter-defibrillator as a lifesaving-bridge therapy for decision in high risk Japanese patients of sudden arrhythmic deathHeart Rhythm2016135S150

- AdelsteinEVoigtASabaSWangNJainSSinghMReply: no utility of the wearable cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy?J Am Coll Cardiol20166723280827282907

- SinghMAlluriKVoigtAAbstract 12637: utility of the wearable cardioverter-defibrillator for patients with newly diagnosed non-ischemic cardiomyopathy?Circulation2014130Suppl 2A12637

- AuricchioAKleinHGellerCJReekSHeilmanMSSzymkiewiczSJClinical efficacy of the wearable cardioverter-defibrillator in acutely terminating episodes of ventricular fibrillationAm J Cardiol19988110125312569604964

- U.S. Food and Drug AdministrationPremarket approval (PMA)2016 [cited August 22, 2016]. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpma/pma.cfm?id=P010030