Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a serious mental illness with adverse impact on the lives of the patients and their caregivers. BD is associated with many limitations in personal and interpersonal functioning and restricts the patients’ ability to use their potential capabilities fully. Bipolar patients long to live meaningful lives, but this goal is hard to achieve for those with poor insight. With progress and humanization of society, the issue of patients’ needs became an important topic. The objective of the paper is to provide the up-to-date data on the unmet needs of BD patients and their caregivers.

Methods

A systematic computerized examination of MEDLINE publications from 1970 to 2015, via the keywords “bipolar disorder”, “mania”, “bipolar depression”, and “unmet needs”, was performed.

Results

Patients’ needs may differ in various stages of the disorder and may have different origin and goals. Thus, we divided them into five groups relating to their nature: those connected with symptoms, treatment, quality of life, family, and pharmacotherapy. We suggested several implications of these needs for pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy.

Conclusion

Trying to follow patients’ needs may be a crucial point in the treatment of BD patients. However, many needs remain unmet due to both medical and social factors.

Introduction

Individuals with bipolar disorder (BD) suffer from a multifaceted, difficult, and somewhat unpredictable course of their disease. It is characterized by substantial, and from time to time, particularly handicapped manic or depressive symptoms. Thus, even patients who follow treatment advice are still at a high relapse risk. Repeated relapses and rehospitalizations are main distresses, indicating a “downward spiral” of declined functioning and greater dependency on support and care by others.Citation1

In the last decades, an increasing attentiveness to human rights and democratic sensibility has given an impulse to the enhancement of the users of mental health care. Both patients and their caregivers began to identify their needs and focused more on their health care utilization. This changed the traditional paternalistic physician–patient relationship by empowering the patients. The progress of the relationship between the providers and consumers of the mental health care has also led to increased attention to human rights. The debate has focused on the requirement for respect and freedom and the so-called existential requests, such as the need to have a meaningful life, and the necessity of spirituality.Citation2 While such needs are important for all individuals, regardless of their health status, they are particularly significant for patients with severe medical disorders, including patients suffering from severe mental illness. Thus, the topic of fundamental human needs takes its place also in patients with BD. The aim of this article was to explore recent scientific facts regarding the needs of the individuals with BD. The sense of our review is to show the broad concept of patients’ needs because of the complexity of problems of patients with BD. We focus not only on the needs connected with the diagnosis and treatment but also on the psychosocial well-being and quality of life.

Methods

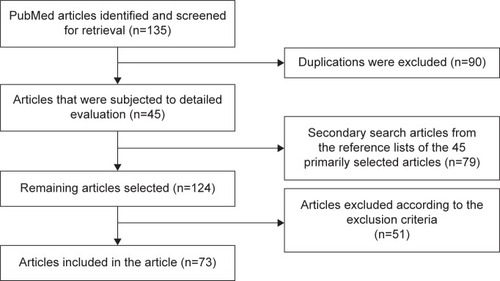

Articles were obtained by using PubMed MEDLINE by systematic searching and extracting papers published in the years between 1970 and 2015. We performed systematic searches using the terms “bipolar disorder”, “mania”, and “bipolar depression”, in successive combination with “unmet needs”. The search was limited to the English language. There were both research studies and reviews. The subjects had to be adults and had to be diagnosed with BD. Furthermore, the papers included had to have been published in peer-reviewed journals; they could be explicit data or reviews on the relevant topic. Excluded were books, book chapters, commentaries, editorials, letters, and dissertations. We utilized a flow diagram to summarize the total number of screened papers and the number of those included in the review process. The procedure for the inclusion of articles is shown in .

Results

We divided the needs into four categories, according to their common elements: needs connected with the symptoms, symptoms’ control, quality of life, and the family. Within these categories, we described especially those patients’ needs that remain both a significant problem in clinical practice and important for patients. In each category, we also identify particular needs, which are more or less met.

Needs connected with the symptoms

A considerable part of the unmet needs is related to the symptoms of the BD. The patients may express worries about enduring symptoms and have trouble in handling them. The needs related to the symptoms may differ at various stages of the illness. They are often linked to the lack of insight, information, and support from family or the medical staff.Citation3,Citation4 Symptoms of the disease can suppress some needs or potentiate others, depending on the stage of the illness.

Specific needs during hypomania and mania

In mania, the patients’ needs often tend to be foremost at the expense of others.Citation5 In hypomania and mania, patients, for example, have a lower need for sleep and eating. Social needs such as contact with others and finding potential intimate short-term relationships are increased, social inhibitions are reduced, and the need for increased activity is evident.

During the (hypo)mania, the long-term patients’ needs are the alleviation and elimination of the symptoms of the illness as well as proper treatment. To satisfy these needs, it is necessary to seek the treatment and adhere to it. However, the need for the treatment is mostly in conflict with the current (hypo) manic mood, thinking, and behavior. The elevated mood discourages patients from seeking stabilizing treatment. Still, some patients, who repeatedly experienced mania in the past, may visit a specialist at the very beginning of hypomania. To do this, they must have established a sufficient level of insight and trust their psychiatrist.Citation6,Citation7 However, even in these rather rare situations, they are frequently ambivalent toward the treatment. They would like to maintain a good mood and increased self-confidence, but they are afraid of the consequences. For psychiatrists, it is important to debate the pluses and minuses of elevated mood and utility of “normal mood” with the patients.

In summary, the most important unmet need in hypomanic and manic states is encouraging acceptance and undergoing of therapy.

Specific needs during depression

Depression is one of the biggest causes of disability in BD and, in comparison with mania, has not as many developed standardized guidelines for the treatment.Citation8 Episodes of depression are usually more frequent, they last longer than manias, and the patients feel worse and have reduced self-confidence. The treatment is further hindered by feelings of inadequacy and worthlessness.

Kulkarni et alCitation9 in their 2-year study focused on relapses and remissions in bipolar I disorder (BD-I) patients. Depressive relapses were twice as frequent as relapses of mania. They also found out that remission from symptomatic mania was more prevalent (92%) than remission from syndromal depression (76.5%).Citation9 Judd et alCitation10 supported these outcomes in a long-term study of BD-I. Their results showed that patients remain symptomatically ill for 47% of the time, and they mostly suffer from depressive symptoms.

The patients’ needs during the depressive episode tend to be similar to the needs of the family and the psychiatrist since they all want to make the symptoms disappear.Citation11 Additionally, the patients need from others tolerance, empathy, enhanced feelings of hope for improvement, safety, help with decreasing feelings of guilt, and endurance that they lack.Citation12

Masand and TracyCitation13 recognized that, despite the level of treatment, the greatest unmet need of the bipolar patients is the problem of the treatment of bipolar depression (identified by 33.3% of patients), with treatment access, treatment affordability, and relapse prevention being identified by about one in five respondents. The result of Leibenluft et alCitation14 showed that patients are concerned the most about decisions on treatment location (inpatient or outpatient) as well as decisions about pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatment.

In summary, the most common unmet need in the depressive stage is early recognition of depression and the encouragement of the decision to seek treatment, and in the case of severe depression acceptance of eventual hospitalization.

Needs during remission

Established or emerging remission is accompanied by favorable life status and improved quality of life.Citation9,Citation15 The basic needs during remission are the maintenance of well-being, mental illness not being experienced as a stigma, return to employment and family life, and decreasing the fear of relapse. For many patients with this stage of disease, it is important to improve self-esteem and decrease self-stigma.Citation16–Citation18 No less important are also adherence to treatment, regular use of medication, and regular follow-up by the treating psychiatrist.

Although patients might consider medication as being useful, they may still refuse it as a way to achieve at least some independence and control over their lives.Citation19 Sometimes patients without sufficient experience may think that there is no need for medication because they are feeling better. However, many patients live more with the worries of relapse, with the subsequent decrease of maintaining quality relationships and the inability to keep their professional status.

In summary, the most significant unmet need during remission is medication without adverse effects.

Needs and residual symptoms

Despite substantial progress in pharmacotherapy for BD, many patients remain symptomatic between episodes.Citation20 Regardless of many existing types of treatment, a considerable number of patients with BD experience only partial symptoms remission or symptoms recurrence.

Bipolar patients often suffer from severe symptoms that make everyday life difficult. After a resolved acute episode, following treatment could be a challenging time for the involvement of patients in ordinary life. Residual symptoms can restrict the capacity to contact and have benefits from community services.Citation21 The patients recognize unmet needs connected to the illness. Families recognize distresses associated with the absence of improvement of the patient at the time. Many patients and families do not fully understand the aims of follow-up or long-term preventive care.

In summary, the most common unmet need in patients with residual symptoms is a lack of the efficacy of the available medication and need for a wider spectrum of easily available psychosocial intervention.

Needs during relapse

Despite the continual adherence to drug schedules in many patients, the probability of relapse after 5 years of follow-up was as high as 73%.Citation22 Life stressors were identified to be the most common cause of relapse (43.2% of relapses).Citation13

Significant sleep disturbance also accompanies BD. Reduced sleep is recognized to be connected with substantial adverse psychosocial, job-related, economic, and health effects.Citation23 An analysis of eleven research studies with 631 BD patients has shown that problems with sleep were the most frequent in prodromes of mania (77% of patients) and the sixth most frequent prodrome of depression episodes (24% of patients).Citation24 Some data indicate that disturbances of sleep are associated with relapse in BD.Citation25 There is a decreased need for sleep during episodes of mania. During the depression, bipolar patients usually have problems with decreased or increased sleep. Unpredictably, recent data suggest that troubles with sleep remain even when patients are in remission.Citation26,Citation27 The time of remission is also imperative because the patients suffer from other substantial symptomatology and impairments, including mood dysregulation.Citation20 There is evidence that education about early recognition of manic relapse signs and seeking early treatment leads to a prolonged period until the next episode of mania, improvement in work-related adjustment, social functioning, and well-being.Citation28 Malkoff-Schwartz et alCitation29 studied that topic and hypothesized that stressful life events linked with social rhythm disruption would frequently be detected in prodromal stages before a BD episode.

Several studies showed that hypersomnia prevails in patients with bipolar rather than in patients with unipolar depression.Citation30,Citation31 Similarly, hypersomnia is mostly recurs through distinct episodes of bipolar depression.Citation14,Citation32 Manipulations of the circadian rhythms have been used to enhance sleep deprivation antidepressant efficacy in patients with BD.Citation33

In summary, the most common unmet needs connected with the relapse are early recognition of the warning signs of relapse, treatment of sleep disturbances, modification of lifestyle to decrease the probability of life stress, and rapid acting medication.

Patient perception of health status

Most of the participants in the study of Shattell et alCitation34 described adverse experiences with the health care professionals and system. Somatic illnesses were ignored when symptoms were qualified as related to the mental health.

In summary, many patients perceived lack of attention and understanding by the health care expert. Some patients complained about enormous efforts to achieve health care for somatic symptoms.

Stigmatization

There are various prejudgments about psychiatric patients in the community. A substantial number of BD patients have to cope with stigma-related behavior by lay peoples as well as health care staff.Citation34 The patients attribute this disorder to not being seen as a human being. These distorted beliefs not only of society but also of patients contribute considerably to the shaping of attitudes toward stigma to which the psychiatric patients are daily exposed. Patients treated in psychiatry are stereotypically perceived as dangerous, illogical, and aggressive.Citation35 This leads to public reservations and small opportunities in life.Citation36 Patients with BD also tend to fear intensely rejection. These patients seek medical services relatively late or not at all. If they have sufficient insight, they may perceive each diagnosed symptom of BD as a painful stigma that pulls down hope for progress in their condition and their self-esteem.

The stigmatization itself usually takes the form of interpersonal coldness or distance for the distressed person. The distancing behavior could be primarily realized in close intimate relationships (spouse, family, and friends) and job relationships. The rejection that originates from the stereotyped understanding of psychiatric disorders also happens in circumstances in which the person acts completely normal. Circumstances at the job and in the family may be somewhat parallel. The patients can be markedly observed after discharge; people around the patient behave vigilantly, review his or her behavior, and relate it to the labels they have.Citation18 Each of the unexpected activities, linked to the illness or not, is directly qualified as the indication of the malady.

Self-stigma is accompanied by lower self-esteem.Citation37 There is confirmation for a positive correlation between the patient’s evaluation of the therapy relation and his/her grade of self-esteem in early psychosis interventions.Citation38 In summary, the most important unmet needs connected with stigmatization are the change of public opinions to the people with mental illnesses and the programs oriented to the decrease of the self-stigmatization.

Needs connected with the symptoms control

There are many needs associated with the control of the symptoms. The basic needs are related to the proper time of treatment intervention, which is helpful, rapidly effective, not complicated, without many side effects and harmless, lacking the need for hospitalizations, and not interrupting the everyday routine.

Various unmet needs related to pharmacological treatment such as, 1) to develop more rapid-acting treatments with better side-effect profiles; 2) to identify drugs for the adequate management of resistant bipolar depression, resistant mania, rapid cycling, and mixed states; and 3) to determine pharmacological treatments targeting the cognitive deficits in BD, are important tasks for the future.

All these qualities can rarely be achieved, but it is important to do the best. To provide the patients with BD accurate, evidence-based health care, recommendations have been established; for instance, the American Psychiatric Association,Citation39 Canmat guidelines,Citation40 and also Algorithms of Czech Psychiatric Association.Citation41 These guiding principles are designed mainly for the drug, biological treatments, and psychotherapy.Citation42

In the qualitative study of Sajatovic et al,Citation43 just over one-third of bipolar patients experienced a lack of relevant information about BD. Most of the patients indicated difficulties remembering to take drugs and sometimes were not sure about the usefulness of taking medications. Others described how ambivalence concerning the importance of drugs and overlooking taking medications both reinforced the nonadherence. Some patients found it difficult to remember a twice-daily drug regimen. Patients faced a multiplicity of difficulties in taking drugs, together with concerns that they had an unnecessary number of prescribed medications, very high doses of medications, and access difficulties plus being unable to pay for drugs or get transportation to appointments. Troublesome side effects involved multiple somatic complaints or specific complications such as tiredness.

Barriers to help-seeking

More research concerning of mental health services will need to identify actionable barriers that prevent access to care. Very often, treatment is started with a significant delay, which prolongs the suffering of the patient.

According to a Dutch study,Citation3 spouses of people with BD described mental health services as unreachable, and the examination of professional support has been described by families as an additional stressor, according to other studies.Citation44,Citation45 The results of the study of Van der Voort et alCitation3 indicate that psychiatry services do not function optimally when they move toward evaluating the needs of caregivers, deliver the information, or create the opportunities for appropriate support.

Sometimes treatment is initiated in a derogatory way (patients are brought to the hospital by the police in handcuffs), relatives curse the patients, and so on. The acute admission to hospital may occur in a painful or traumatic way that complicates the collaboration with the treatment.

Important factors influencing help-seeking include the family environment and the view of household members of the need for the treatment of mental health problems, attitudes toward medication use, patient’s self-image and the desire to manage everything without outside assistance, insight into symptoms of mental illness, awareness of the need to take medication, previous experience and myths regarding the treatment of mental illness in society, and also the stigma of mental illness.

Needs during hospitalization

Patients need to orient themselves during hospitalization; this will help them to increase the sense of security. Adequate treatment is necessary as well as sufficient contact with other patients met during the hospitalization. It is also crucial for the whole medical staff to exhibit respect for the patient’s condition. Despite the restrictions, it is necessary to provide patients the maximal possible degree of freedom. Positive interest and understanding are essential. Last but not least, it is important to reward patients appropriately for independence, create friendly but sufficient restrictions in case of suicidality or aggression, and also help the patients to solve urgent social problems. Sometimes it is necessary to calm, graciously, family members.

Needs in follow-up care

At the time of deinstitutionalization, patients with BD were confronted with the complications of existing in the community, and their psychiatric managing had to adapt. As psychiatric services enlarged in availability and diversity, the organization has become more service-oriented. In addition to the previously recognized clinical features, simplifying the right of entry to social contacts, housing, and jobs was included in the management of patients with BD.Citation46

Progressively, the inpatient treatment for an episode of BD is restricted to days rather than months. For some people, it means that residual symptoms can remain and negatively affect their capabilities to adapt for day-to-day living in the community. Next episodes and new hospitalizations are principal characteristics of the disease course of BD patients. Relapse rates are high and range from 40% to 80% in 1 year after hospitalization.Citation47 The early post-discharge stage of the management can be critical for long-term adjustments in the community setting.Citation46 Explanations for these early relapses are uncertain but could be associated with the distress connected with going back into the community after intensive inpatient treatment. The management of BD patients can be enriched if it is based on a broad knowledge of the patients’ experiences of transition from hospital to community, as well as on the related needs that they recognize as unmet. The first days after discharge from inpatient treatment facilities can be an especially fragile time for bipolar patients, even with arranged follow-up care transitioning.

The good therapeutic relation is important for the start of the successful pharmacohological and psychotherapeutic treatment outcome. The relation between therapeutic relation and treatment outcome is a strong result of the psychotherapy investigations.Citation48 The management of the therapeutic relation in patients with BD has various demands. The best framework,Citation19 1) assimilates current scientific results of the therapeutic relation, 2) tailors therapeutic activity for each patient personally, both proactively and reactively, 3) uses the results of basic science, and 4) is well-matched with the variety of strategies (eg, pharmacological and psychotherapeutic).

Adherence

Medication is a basis of treatment for BD patients. However, there is ubiquitous nonadherence with recommended treatment, which leads to adverse consequences, such as recurrence or relapse of the disorder.Citation39,Citation49 The significant rate of medication discontinuation and the associated treatment complications could indicate unmet needs for patients with BD. There are a lack of studies focused especially on nonadherence in BD, and only a few studies have additionally focused on individuals’ perceptions of the disorder and drug treatment adherence.Citation50,Citation51

Medication refusal might completely saturate need of the patients autonomy.Citation48 Nevertheless, another BD patient might reject drugs to gain extra meetings with a psychiatrist or to develop a better connection with family, to complete his/her need for attachment. Moreover, many patients can simply want to avoid adverse side effects.Citation19 Thus, one difficult behavior can work for very diverse motivational reasons. Also, difficult behavior can be multiply determined (eg, serving autonomy and affiliation). Nonadherent patients are less likely to be included in research studies, which restricts the chances to develop evidence-based methods for enhancement in adherence. Patient-focused qualitative approaches may lead to many different but also valuable insights into patients’ beliefs about therapy.Citation52 Without clinicians understanding why a patient is adherent or not to the prescribed drugs, it is hard to prepare strategies that address nonadherence.

Quantitative analysis in the study of Sajatovic et alCitation43 has shown that problems with medication schedules, worries about medication adverse effects, and denial of the psychiatric illness or its severity were the most significant influences on the negative beliefs toward medication of BD patients. Qualitative findings indicated that nonadherence was substantially influenced by side effects such as drowsiness and weight gain, as well as by belief that medications were not needed.

The study of Sajatovic et alCitation43 also showed that overlooking taking the drugs was the main self-reported cause for nonadherence (55%). The qualitative evaluation indicated that adverse effects experienced by patients (20%) are the second highest frequent cause for nonadherence. Another cause involved reluctance to use the drugs for a lifetime and wishing to experience symptoms of mania.

A lot of nonadherent BD patients did not perceive that they have owned control of their disease.Citation53 While most patients experienced drugs as being useful, with direct effects on symptoms, functioning, and anxiety levels, this was countered by worries about possible difficulties and not having control over their life. Stimulating positive views that encourage suitable pharmacotherapy, supporting BD patients to have control over the disorder, and allaying mistaken health opinions through psychosocial approaches, could increase treatment collaboration among persons who feel helpless about the disease.Citation12,Citation54 Zeber et alCitation55 described that drug adherence is associated with the therapeutic relationship since better adherence was observed when psychiatrists repeatedly evaluated improvement and encouraged communication.

In a survey of psychiatrists, Chengappa and WilliamsCitation8 also found effective treatment options to be a major barrier to the efficient management of BD. Clinically effective treatments are also thought to lower the burden on caregivers of individuals with BD.Citation56

Needs connected with the quality of life

This category could be demarcated as any apprehensions, worries, or difficulties that patients recognized as not related to a particular symptom of illness but adversely affecting the capability to integrate into the community, and/or decreasing the quality of life. Occupation, finance, and other daily events are examples of the distress articulated by the BD patients in the qualitative study of Gerson and Rose.Citation21

Many BD patients coped with the problems of abuse (sexual, physical, and emotional), divorce, distancing from family, loss of children, rape, and homelessness.Citation34

The disorder interferes with life experiences of many patients, who reported interference with study plans, interpersonal relationships, career, and the establishment of their own family.Citation34

Needs connected with the family

This category could be distinct from the means in which family members or close relatives be of assistance to the patient to reintegrate into society and to manage their illness.

Family members have grown to be more central in care. The investigation indicates that providing support to people who take care of patients with severe psychiatric diseases should be a relevant part of the management.Citation57

Support comes in the form of help with specific tasks such as handling money or fulfilling prescriptions. In the qualitative study of Gerson and Rose,Citation21 patients also reported about the assistance of family supporters who visited them while they were in the hospital. Finally, patients also described support as being satisfied in speaking with family members about their diseases. Perlick et alCitation7 and Van der Voort et alCitation3 showed that most of the caring persons feel a modest level of burden, not only throughout the episodes of depression or mania but also constantly. This problem is linked to symptomatic behavior, reduced efficiency in responsibilities the individual being cared for, and adverse costs for family and household. In all three previous studies, the link seems to be concerning how families evaluate the circumstances and the burden they live through.Citation5,Citation58–Citation60 The belief that people with BD are principally capable of controlling their behavior connected with BD has been recognized to be linked to the higher intensities of problems and disappointment with the relationship.Citation6

Family coping styles can be acknowledged and used to organize strategies to decrease the burden on the family as they support the treatment of the patient symptoms and increase the adherence to treatment.Citation61

Implications for pharmacotherapy

The ability of the psychiatrist to recognize the psychiatric patient needs reduces the risk of missing of various problems, for instance, arbitrary withdrawal of medication. Unpleasant cycles of the difficult patient and problematic therapist behaviors (eg, the psychiatrist impels the patient to be cooperating in using drugs, the patient refuses drugs to experience himself as independent).

Side effects

In a study by McIntyre,Citation62 UNITE Internet survey recruited patients from eleven countries, and a total of 5,074 participants responded (1,155 individuals with schizophrenia and 1,300 with BD were self-identified). Psychiatrists were acknowledged as the people primarily responsible for patients’ drug prescriptions and observation of both psychological and somatic health. The bulk of respondents in both groups had been receiving medication for >5 years. Weight increase was the most frequently cited side effect related to the administration of drugs. Moreover, weight gain was also recognized as a contributing factor to general medical health (eg, diabetes mellitus) and as a detractor of the quality of life. Most respondents recognized weight gain and general physical health as areas of insufficiency in their practical information and interactions with health care providers. Despite the ubiquity and implications of comorbid medical illnesses and medication-related adverse events, most respondents did not obtain occasional screening or observation for medical risk factors and diseases. Overall, respondents reported general dissatisfaction when interacting with mental health care providers. The author concludes that metabolic consequences of psychotropic medicine are the most concerning feature of drug treatment for patients, leading to perceived morbidity, a decrease of the quality of life, and decreased satisfaction with the treatment. Regardless of the compelling data that highlights the hazards due to comorbid physical conditions, most persons with BD take guideline-discordant treatment for somatic health illnesses as well as for the principal psychiatric disorder. Barriers to somatic health care for people with schizophrenia and BD, as well as the effect of targeted interventions, warrant future research.

In the study of Masand and Tracy,Citation13 weight gain from antipsychotics (33.3%) and mood stabilizers (46.4%) was the most problematic side effect for respondents. It is surprising that more respondents were more worried about weight gain on mood stabilizers than weight gain on antipsychotics, despite the fact that weight gain with many novel antipsychotics such as clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine is much more problematic than with the traditional mood stabilizers.Citation63

Parkinsonian adverse symptoms were a primary distress in 17% of the respondents receiving antipsychotic treatment. Although the second-generation antipsychotics cause less extrapyramidal symptoms, their prevalence remains substantial.Citation14 Clinicians need to be less accepting of extrapyramidal symptoms with the novel antipsychotics; subsequently, they can be a cause of abundant morbidity and even suicidality.

While a significant number of respondents did not answer a question about arbitrary withdrawal of medication, the second most common answer about nonadherence yielded the rate of 30%–70%, conceivably indicating that numerous respondents themselves had been drug nonadherent. This finding is supported by a documented range of 36%–80% nonadherence according to Sylvia et al.Citation64 Only 7.5% of people assumed that medication nonadherence occurred in <20% of patients.

Dosage

Doses of medication for mania are sometimes prescribed at the upper limit of the recommended dose range and sometimes exceed it. This can be done not only with one drug but also with several drugs. This practice significantly increases the occurrence of side effects. High doses should be reduced for the future. However, this often does not happen because of avoiding relapse.

Combinations

Patients typically need more than one medication to maintain remission, and the practice of adding a second-generation antipsychotic to lithium, sodium valproate, and/or antidepressant is common. The drugs that target the manic and mixed episodes of BD have a stronger scientific base than those for the management of depression.Citation13

The survey by Masand and TracyCitation13 showed that most patients with BD are taking three or more medications, and it is common (13.3%) that patients with BD take five or more drugs. These outcomes are comparable to the results of Levine et al,Citation65 who found that nearly 50% of study participants received three or more psychotropic drugs; polypharmacy was not linked to demographic factors such as sex, age, educational or marital status, or medication prescriptions.

Implications for psychotherapy

Psychoeducation and approaches such as interpersonal therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) have been shown to decrease relapse and recurrence rates significantly when added to medication in patients with BD.Citation66–Citation68 Unfortunately, they are underutilized because of the lack of trained therapists, cost, and compensation issues. The addition of CBT to treatment as usual (TAU) was supposed to be cost-effective because of decreases in using of services.Citation66

Individual CBT for BD builds on Beck’s cognitive therapy; a skills-based therapy supports people in identifying and changing the association between maladaptive beliefs and moods. Using mood diaries, activity scheduling, and thought records, BD patients learn to change automatic negative thoughts, eliminate distorted thinking, and block episodes of mania and depression.Citation69

Lam et alCitation67 randomized 103 BD patients with a history of recurrent episodes (at least two episodes in 2 years or three episodes in 5 years) to individual CBT or TAU. CBT was managed as 12–18 meetings over 6 months followed by two booster sessions. The risk of relapse was significantly lower in the CBT compared with TAU over 12 months. Those allocated to CBT also had lower rates of relapse compared with TAU (64% vs 84%) and a longer time to the depressive episode than TAU over 30 months follow-up.

Group CBT, while not as extensively verified as individual CBT, has confirmed effectiveness for BD. The study of Williams et alCitation70 summarized earlier exhibited greater outcomes to TAU on measures of depressive and anxiety symptoms, functioning, and time to relapse. Several findings advocate that group CBT would be a valuable addition to pharmacotherapy for the treatment of BD.Citation71–Citation73

Conclusion

Overlooking taking of prescribed drugs and difficulties with adverse effects are major impediments to treatment. The absence of medication schedules, uncooperative social systems, lack of illness understanding, and treatment complications may also affect overall adherence. Yet, there are various unmet needs in the management of BD. Moreover, there are discrepancies among the evidence-based treatments for BD and patient perception of the relative effectiveness of different drugs. There is a need to arrange for psychiatrists, patients, and patients’ families better psychoeducation about the best evidence-based treatments for BD.

Disclosure

The authors proclaim that the article was written without any profitable or financial relations that could be understood as a possible conflict of interest. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- U. S. Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon GeneralMental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon GeneralRockville, MDDepartment of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service2001

- Torres-GonzálezFIbanez-CasasISaldiviaSUnmet needs in the management of schizophreniaNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2014109711024476630

- Van der VoortTYGoossensPJvan der BijlJJAlone together: a grounded theory study of experienced burden, coping, and support needs of spouses of persons with a bipolar disorderInt J Ment Health Nurs200918643444319883415

- Van der VoortTYGGoossensPJJvan der BijlJJCoping, burden, and needs for support of caregivers of persons with bipolar disorder: a systematic reviewJ Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs200714767968717880662

- KarpDATanarugsachockVMental illness, caregiving, and emotion managementQual Health Res200010162510724753

- LamDDonaldsonCBrownYMalliarisYBurden and marital and sexual satisfaction in the spouses of bipolar patientsBipolar Disord20057543144016176436

- PerlickDARosenheckRAMiklowitzDJPrevalence and correlates of burden among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder enrolled in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorderBipolar Disord20079326227317430301

- ChengappaKRWilliamsPBarriers to the effective management of bipolar disorder: a survey of psychiatrists based in the UK and USABipolar Disord20057suppl 1384215762867

- KulkarniJFiliaSBerkLTreatment and outcomes of an Australian cohort of outpatients with bipolar I or schizoaffective disorder over twenty-four months: implications for clinical practiceBMC Psychiatry201212122823244301

- JuddLLAkiskalHSSchettlerPJThe long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorderArch Gen Psychiatry200259653053712044195

- CuijpersPStamHBurnout among relatives of psychiatric patients attending psychoeducational support groupsPsychiatr Serv200051337537910686247

- BauerMSKilbourneAMLudmanEGreenwaldDOvercoming Bipolar Disorder: A Comprehensive Workbook for Managing Your Symptoms and Achieving Your Life GoalsOakland, CANew Harbinger Publications, Inc2008

- MasandPSTracyNResults from an online survey of patient and caregiver perspectives on unmet needs in the treatment of bipolar disorderPrim Care Companion CNS Disord201482816410.4088/PCC.14m01655 eCollection 2014

- LeibenluftEClarkCHMyersFSThe reproducibility of depressive and hypomanic symptoms across repeated episodes in patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorderJ Affect Disord199533283887759665

- SchafferAMcIntoshDGoldsteinBICanadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Task Force: The CANMAT task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid anxiety disordersAnn Clin Psychiatry201224162222303519

- LatalovaKPraskoJGrambalABipolar disorder and anxiety disordersNeuro Endocrinol Lett201334873874424522015

- LatalovaKOciskovaMPraskoJKamaradovaDJelenovaDSedlackovaZSelf-stigmatization in patients with bipolar disorderNeuro Endocrinol Lett201334426527223803872

- HajdaMKamaradovaDLatalovaKSelf-stigma, treatment adherence, and medication discontinuation in patients with bipolar disorders in remission – a cross-sectional studyAct Nerv Super Rediviva2015571–2611

- WestermannSCaveltiMHeibachECasparFMotive-oriented therapeutic relationship building for patients diagnosed with schizophreniaFront Psychol20156129426388804

- MacQueenGMMarriottMBeginHRobbJJoffeRTYoungLTSubsyndromal symptoms assessed in longitudinal, prospective follow-up of a cohort of patients with bipolar disorderBipolar Disord20035534935514525555

- GersonLDRoseLENeeds of persons with serious mental illness following discharge from inpatient treatment: patient and family viewsArch Psychiatr Nurs201226426127122835746

- GitlinMJSwendsenJHellerTLHammenCRelapse and impairment in bipolar disorderAm J Psychiatry199515211163516407485627

- Ancoli-IsraelSRothTCharacteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey ISleep199922suppl 2S347S35310394606

- JacksonACavanaghJScottJA systematic review of manic and depressive prodromesJ Affect Disord200374320921712738039

- HarveyAGSleep and circadian rhythms in bipolar disorder: seeking synchrony, harmony, and regulationAm J Psychiatry2008165782082918519522

- MillarAEspieCAScottJThe sleep of remitted bipolar outpatients: a controlled naturalistic study using actigraphyJ Affect Disord2004802–314515315207927

- HarveyAGSchmidtDAScarnàASemlerCNGoodwinGMSleep-related functioning in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder, patients with insomnia, and subjects without sleep problemsAm J Psychiatry20051621505715625201

- PerryATarrierNMorrissRMcCarthyELimbKRandomized controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatmentBMJ199931871771491539888904

- Malkoff-SchwartzSFrankEAndersonBStressful life events and social rhythm disruption in the onset of manic and depressive bipolar episodes: a preliminary investigationArch Gen Psychiatry19985587027079707380

- BenazziFSymptoms of depression as possible markers of bipolar II disorderProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200630347147716427176

- BowdenCLA different depression: clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depressionJ Affect Discord2005842117125

- KaplanKAGruberJEidelmanPTalbotLSHarveyAGHypersomnia in inter-episode bipolar disorder: does it have prognostic significance?J Affect Disord2011132343844421489637

- Wirz-JusticeABenedettiFBergerMChronotherapeutics (light and wake therapy) in affective disordersPsychol Med200535793994416045060

- ShattellMMStarrSSThomasSP‘Take my hand, help me out’: mental health service recipients’ experience of the therapeutic relationshipInt J Ment Health Nurs200716427428417635627

- NawkováLNawkaAAdámkováTThe picture of mental health/illness in the printed media in three central European countriesJ Health Commun2012171224021707410

- SchulzeBAngermeyerMCSubjective experiences of stigma: a focus group study of schizophrenic patients, their relatives, and mental health professionalsSoc Sci Med200356229931212473315

- LinkBGStrueningELNeese-ToddSAsmussenSPhelanJCStigma as a barrier to recovery: the consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnessesPsychiatr Serv200152121621162611726753

- LecomteTLaferrière-SimardMCLeclercCWhat does the alliance predict in group interventions for early psychosis?J Contemp Psychother20124225561

- American Psychiatric Association (APA)Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision)Am J Psychiatry20021594 Suppl150

- YathamLNKennedySHO’DonovanCCanadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: consensus and controversiesBipolar Disord20057suppl 356915952957

- DoubekPPraskoJMasopustJBipolarni afektivni porucha (manicka, smisena a depresivni [Bipolar affective disorder (manic, mixed, and depressive)]RabochJUhlikovaPHellerovaPAndersMSustaMDoporučené postupy psychiatrické péčePrahaCeska psychiatricka spolecnost20148298

- RegeerEJten HaveMRossoMLVolleberghWNolenWAPrevalence of bipolar disorder in the general population: a reappraisal study of the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence studyActa Psychiatr Scand2004110537438215458561

- SajatovicMLevinJFuentes-CasianoECassidyKATatsuokaCJenkinsJHIllness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medicationCompr Psychiatry201152328028721497222

- RoseLBenefits and limitations of professional-family interactions: the family perspectiveArch Psychiatr Nurs19981231401479628044

- VeltmanACameronJIStewartDEThe experience of providing care to relatives with chronic mental illnessJ Nerv Ment Dis2002190210811411889365

- BruffaertsRSabbeMDemyttenaereKEffects of patient and health-system characteristics on community tenure of discharged patientsPsychiatr Serv200455668569015175467

- IrmiterCMcCarthyJFBarryKLSolimanSBlowFReinstitutionalization following psychiatric discharge among VA patients with serious mental illness: a national longitudinal studyPsychiatr Q200778427928617763982

- FlückigerCDel ReACWampoldBESymondsDHorvathAOHow central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysisJ Couns Psychol2012591101721988681

- LingamRScottJTreatment non-adherence in affective disordersActa Psychiatr Scand2002105316417211939969

- BerkMBerkLCastleDA collaborative approach to the treatment alliance in bipolar disorderBipolar Disord20046650451815541066

- SajatovicMJenkinsJHCassidyKAMuzinaDJMedication treatment perceptions, concerns, and expectations among depressed individuals with type I bipolar disorderJ Affect Disord2009115336036618996600

- ClatworthyJBowskillRRankTParhamRHorneRAdherence to medication in bipolar disorder: a qualitative study exploring the role of patients’ beliefs about the condition and its treatmentBipolar Disord20079665666417845282

- DarlingCAOlmsteadSBLundVEFaircloughJFBipolar disorder: medication adherence and life contentmentArch Psychiatr Nurs200822311312618505693

- SachsGSPsychosocial interventions as adjunctive therapy for bipolar disorderJ Psychiatr Pract200814suppl 2394418677198

- ZeberJECopelandLAGoodCBFineMJBauerMSKilbourneAMTherapeutic alliance perceptions and medication adherence in patients with bipolar disorderJ Affect Disord20081071–3536217822779

- LoebelACucchiaroJSilvaRLurasidone monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar I depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyAm J Psychiatry2014171216016824170180

- ReaMMMiklowitzDJThompsonMCGoldsteinMJHwangSMintzJFamily-focused treatment versus individual treatment for bipolar disorder: results of a randomized clinical trialJ Consult Clin Psychol200371348249212795572

- GreenbergJSKimHWGreenleyJRFactors associated with subjective burden in siblings of adults with severe mental illnessAm J Orthopsychiatry19976722312419142356

- PerlickDAClarkinJFSireyJGreenfieldPStrueningSRosenheckRBurden experienced by caregivers of persons with bipolar affective disorderBr J Psychiatry19991757566210621769

- ChakrabartiSGillSCoping and its correlates among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder: a preliminary studyBipolar Disord200241506012047495

- NehraRChakrabartiSKulharaPLSharmaRCaregiver-coping in bipolar disorder and schizophreniaSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidem2005404329336

- McIntyreRSUnderstanding needs interactions, treatment, and expectations among individuals affected by bipolar disorder or schizophrenia: the UNITE global surveyJ Clin Psychiatry200970suppl 351119570496

- HasnainMViewegWVWeight considerations in psychotropic drug prescribing and switchingPostgrad Med2013125511712924113670

- SylviaLGReilly-HarringtonNALeonACMedication adherence in a comparative effectiveness trial for bipolar disorderActa Psychiatr Scand2014129535936524117232

- LevineJChengappaKNBrarJSPsychotropic drug prescription patterns among patients with bipolar I disorderBipolar Disord20002212013011252651

- LamDHHaywardPWatkinsERWrightKShamPRelapse prevention in patients with bipolar disorder: cognitive therapy outcome after 2 yearsAm J Psychiatry2005162232432915677598

- LamDHWatkinsERHaywardPA randomized controlled study of cognitive therapy for relapse prevention for bipolar affective disorder: outcome of the first yearArch Gen Psychiatry200360214515212578431

- VietaEPacchiarottiIValentíMBerkLScottJColomFA critical update on psychological interventions for bipolar disordersCurr Psychiatry Rep200911649450219909673

- BeckATRushAJShawBFGaryECognitive Therapy of DepressionNew York, NYGuilford Press1979

- WilliamsJMAlatiqYCraneCMindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in bipolar disorder: preliminary evaluation of immediate effects on between-episode functioningJ Affect Disord20081071–327527917884176

- CostaRTCheniauxERosaesPAThe effectiveness of cognitive behavioral group therapy in treating bipolar disorder: a randomized controlled studyRev Bras Psiquiatr201133214414921829907

- GomesBCAbreuLNBrietzkeEA randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral group therapy for bipolar disorderPsychother Psychosom201180314415021372622

- González IsasiAEcheburúaELimiñanaJMGonzález-PintoAPsychoeducation and cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with refractory bipolar disorder: a 5-year controlled clinical trialEur Psychiatry201429313414123276524