Abstract

The aim of the study was to evaluate the clinical value of multiple brain parameters on monitoring intracranial pressure (ICP) procedures in the therapy of severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI) utilizing mild hypothermia treatment (MHT) alone or a combination strategy with other therapeutic techniques. A total of 62 patients with sTBI (Glasgow Coma Scale score <8) were treated using mild hypothermia alone or mild hypothermia combined with conventional ICP procedures such as dehydration using mannitol, hyperventilation, and decompressive craniectomy. The multiple brain parameters, which included ICP, cerebral perfusion pressure, transcranial Doppler, brain tissue partial pressure of oxygen, and jugular venous oxygen saturation, were detected and analyzed. All of these measures can control the ICP of sTBI patients to a certain extent, but multiparameters associated with brain environment and functions have to be critically monitored simultaneously because some procedures of reducing ICP can cause side effects for long-term recovery in sTBI patients. The result suggested that multimodality monitoring must be performed during the process of mild hypothermia combined with conventional ICP procedures in order to safely target different clinical methods to specific patients who may benefit from an individual therapy.

Introduction

Severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI) is a public health problem with a high rate of mortality and disability worldwide, as well as inflicting damage on patients and their family.Citation1–Citation3 Control of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) are the fundamental therapeutic goals for sTBICitation4 because ICP can cause a series of sequelae through destroying intracranial environment and inducing secondary brain injury. The major conventional clinical techniques of controlling ICP include dehydration using mannitol, hyperventilation, and decompressive craniectomy (DC). Mild hypothermia (33°C–35°C) has been recognized as a powerful neuroprotective method in sTBI.Citation5–Citation7 It can alleviate a series of adverse reactions, prevent high ICP, and reduce the secondary damage by influencing release of excitatory neurotransmitters,Citation8 decrease the cerebral metabolic rate,Citation9 and relieve the opening of the blood–brain barrier.Citation10 Currently, the procedure of mild hypothermia combined with other measures of ICP has been a consensus for sTBI treatment.Citation11 However, individualized treatment strategy of ICP is useful because of the various complex conditions in sTBI patients. How to monitor and evaluate the clinical effects of different measures of ICP is critically important. Cerebral monitoring parameters mainly include ICP, CPP, transcranial Doppler, brain tissue partial pressure of oxygen (PbtO2), jugular venous oxygen saturation (SjvO2), and microdialysis monitoring technology.Citation12 Any single parameter of these can hardly monitor clinical efficiency of ICP. A novel pattern of combining multiparameters for the treatment of sTBI is necessary.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical value of multiple brain parameters on monitoring the procedures of ICP in the therapy of sTBI. In order to establish a novel pattern of multiparameters as a standard monitoring guide, we collected and analyzed the multiparameters from the clinical cases of sTBI treated with mild hypothermia alone or mild hypothermia combined with other conventional procedures of controlling ICP.

Patients and methods

Patients and inclusion criteria

All 62 hospitalization cases of sTBI were selected from the Brain Hospital of the Affiliated Hospital of Logistics University of People’s Armed Police Force from September 2009 to November 2010. The selected inclusion criteria included 1) acute sTBI patients (Glasgow Coma Scale score ≤8 on hospital admission); 2) patients admitted within 2–3 hours after injury; 3) all patients except those with severe chest, abdomen, and other viscera trauma, as well as severe arrhythmia, coronary heart disease, and diabetes. This study was approved by the Affiliated Hospital of Logistics University of People’s Armed Police Force. All patients had signed the informed consent form.

Therapeutic methods

Therapeutic procedures were based on the craniocerebral trauma care standards and the China brain injury surgical guide (expert consensus). In all patients, mild hypothermia treatment (MHT) was performed. A total of 36 cases were treated conservatively, and 26 cases in line with indications were treated with the procedure of DC. During admission to neonatal intensive-care unit, the patients with ICP >20 mmHg and CPP <60 mmHg were treated with active intervention. In addition to surgical intervention during treatment, ICP measures were mainly dominated by mild hypothermia and hypertonic dehydration, still invalid cases complemented by measures such as hyperventilation.

DC surgery

During standard large trauma craniotomy, the size of the bone flap was at least 12×15 cm2.

Mild hypothermia therapy

During treatment with mild hypothermia therapy, the room temperature was controlled at 17°C by using a room-type, high-power air conditioner. The patients were placed on a controlling temperature blanket (Blanketrol-II; CSZ, Cincinnati, OH, USA) to be physically cool, and continuous intravenous infusion of cockstailytic (normal saline 500 mL + chlorpromazine 100 mg + promethazine 100 mg) or sedative drugs (normal saline 100 mL + morphine sulfate 100 mg) to decrease the rectal temperature of patients to 35°C within 6 hours and maintain them at 33°C–35°C was used. For patients with cooling problem, intravenous injection of fen phthalic 0.2 mg or loose 8 mg was used to block autonomous respiration. At the same time, a ventilator (Drager Evita 2 Cap; Lübeck, Dräger, Germany) controlled breathing, while there was continuous intravenous infusion of hibernating muscle loose mixture (saline 500 mL + chlorpromazine 100 mg + promethazine 100 mg + vecuronium 40 mg). The usage of dosage and infusion rate for cockstailytic, hibernating muscle loose mixture agent, sedative drug were controlled by an infusion pump and adjusted according to the patient’s heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension. The standard for performance was to keep patients with stable vital signs, without agitation and muscle trembling. When ICP has been decreased to the normal level for 48 hours, rewarming was accessed by increasing the temperature of control blanket beyond the rectal temperature of patients to 36.5°C–37°C in 12 hours. Rewarming could not be too fast to prevent the occurrence of complications.

Assessment criteria

A total of five parameters (ICP, PbtO2, SjvO2, CPP, and end-tidal carbon dioxide pressure [ETCO2]) were used to monitor clinical effect on different treatment procedures. The monitoring period was extended from the beginning of mild hypothermia to ≥1–7 days. ICP was detected by the technique of brain interior hydraulic transmission using IntelliVue MP30 System (Philips Company, CO, USA). Meanwhile, left radial artery catheterization was utilized to measure mean arterial pressure for monitoring CPP with the same mechanism. PbtO2 was continuously measured by inserting a 0.5 mm diameter probe into the undamaged frontal lobe of brain tissue with a subcortical depth of 27–36 mm. The probe was connected with the brain tissue oxygen and brain temperature monitor LICOX CMP&IMC (San Diego, CA, USA). SjvO2 was continuously tested using the Nova-H monitor (Waltham, MA, USA). We collected data from all the 62 cases at 12,096 time points (four times per hour, continuously for 72 hours).

Statistical analyses

All measurement data were analyzed using SPSS 10.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and presented as mean values ± SEM. Data sampling rates were compared using chi-square test. The variation in group means and their associated procedures was analyzed using variance of repeated measurement data. Prognosis was compared using the rank sum test; the difference was statistically significant with P<0.05.

Results

Patient’s clinical characteristics

All 62 hospitalization cases of sTBI included 30 cases of traffic injury, 20 cases of contusion injury, and 12 cases of falling injury, consisting of 37 male cases and 25 female cases aged 18–72 years (36.8±12.69 years) with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3–8 (5.20±1.92) on admission. All cases were examined by computed tomography. The result showed that five cases were epidural hematoma, ten cases were subdural hematoma, four cases were parenchymal hematoma, eleven cases were cerebral contusion, eight cases were diffuse axonal injury, 13 cases were multiple trauma, 14 cases were basilar skull fracture, and eight cases were cerebral hernia ().

Table 1 Characteristics of patients

Changes in parameters of mild hypothermia therapy

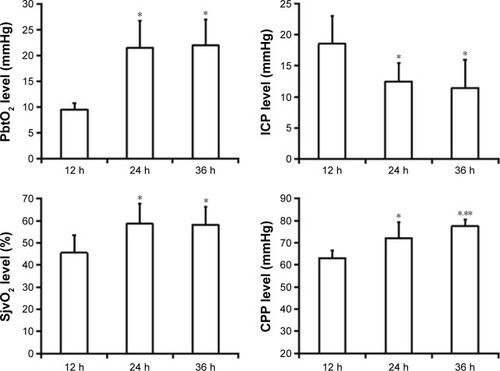

We performed hypothermia treatment for all the 62 sTBI patients and analyzed the change in brain parameters (). Within 24 hours after MHT, ICP declined obviously and PbtO2, SjvO2, and CPP increased significantly. Furthermore, PbtO2 and SjvO2 after 24 hours and 36 hours of treatment, respectively, remained stable; no obvious change happened. The difference was statistically significant.

Figure 1 Change in PbtO2, SjvO2, ICP, and CPP of patients at time 12 hours, 24 hours, and 36 hours after mild hypothermia therapy.

Abbreviations: PbtO2, brain tissue partial pressure of oxygen; SjvO2, jugular venous oxygen saturation; ICP, intracranial pressure; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; h, hours.

Clinical effect of decreasing ICP using mild hypothermia combined with dehydration using mannitol

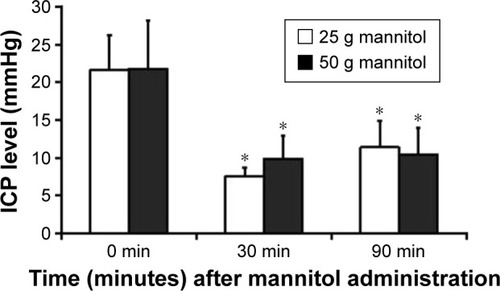

Regarding futile cases of MHT on controlling ICP, we performed dehydration using mannitol (quick infusion within 15 minutes). Two different dosages (25 g and 50 g) of mannitol were used to perform drug dehydration for the patients who had ICP >20 mmHg. After 30 minutes of treatment, ICP in the patients of the two groups was significantly reduced. After 90 minutes, ICP of 25 g mannitol group rebounced, but ICP of 50 g group remained stable at a lower level. Comparing them before dosing, all had significant difference. At the same time, the average age, average weight, and average dose based on weight were higher in the 50 g group than the 25 g group; the differences had no statistical significance ().

Figure 2 Change in ICP of patients with mild hypothermia therapy following mannitol administration.

Abbreviations: ICP, intracranial pressure; PbtO2, brain tissue partial pressure of oxygen; SjvO2, jugular venous oxygen saturation; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure.

Controlling ICP by mild hypothermia therapy followed by hyperventilation

For invalid sTBI patients after MHT combined with mannitol drug, we further tried to control ICP using mild hypothermia coupled with hyperventilation. In all the selected patients, surgery of endotracheal intubation was performed, and then, they were treated with mechanically assisted aeration utilizing breathing machine after tracheotomy. In order to assist ICP by hyperventilation, we operated a variety of breathing patterns by adjusting the breathing machine. Meanwhile, we detected the ICP and variation in PbtO2, as well as analyzed the relationship between ETCO2 and rate of low PbtO2. ICP after excessive ventilation was observed to be improved. In low temperature condition, the ICP value in the ETCO2 30–34 mmHg group decreased significantly compared with that in the ETCO2 25–29 mmHg group; the difference was statistically significant ().

Table 2 ETCO2 and PbtO2 (mmHg, mean ± SD) during hyperventilation therapy in the condition of mild hypothermia

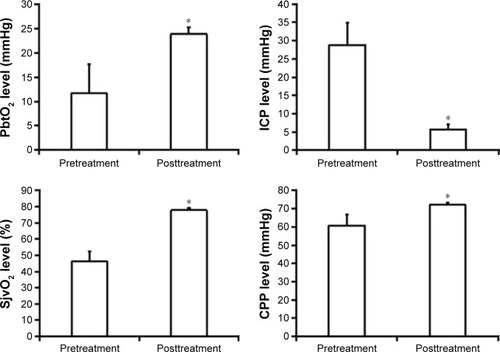

Impact of mild hypothermia therapy followed by DC for controlling ICP and changing brain parameters

We performed mild hypothermia therapy combined with DC to control ICP in 26 sTBI cases who were invalid after MHT, dehydration using mannitol, or hyperventilation therapy. The result of therapy showed that ICP decreased significantly but CPP, PbtO2, and SjvO2 increased variously in all the 26 patients; the differences were statistically significant ().

Figure 3 Change in PbtO2, SjvO2, ICP, and CPP of patients with mild hypothermia therapy followed by DC treatment (n=26).

Abbreviations: PbtO2, brain tissue partial pressure of oxygen; SjvO2, jugular venous oxygen saturation; ICP, intracranial pressure; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; min, minutes; DC, decompressive craniecyomy.

Discussion

Controlling ICP in craniocerebral trauma is particularly important because a high ICP correlates to worse prognoses and is an important cause of death after sTBI.Citation4 Using cool temperature for therapy of patients with sTBI was described as early in 1945. Neuroprotective effect of hypothermia in combination with its ICP-reducing effect has become a major therapeutic option for sTBI patients.Citation13–Citation16

However, a number of controversies still exist regarding the clinical effect of the hypothermia for increased ICP as well as the mechanisms by which mild hypothermia may protect the brain after trauma.Citation17 Several data showed that hypothermia could improve neurological outcome and had a trend of lower mortality rates,Citation18 but some other studies found no difference in the clinical effect, especially in the pediatric population.Citation19

In the current study of 62 patients, we found that ICP declined significantly, but PbtO2, SjvO2, and CPP rose obviously after hypothermia treatment within 24 hours. The brain functional parameter also suggested that the cryogenic treatment could not only reduce ICP but also markedly improve intracranial environment.

Many factors can directly affect the efficiency of hypothermia treatment, such as time of cryogenic treatment, duration, degree, as well as rewarming time.Citation20 After summarizing our practice in hypothermia performance, we thought that the key point of leading to the different therapeutic outcomes is associated with methodology. In spite of not a standard program for sTBI, it is undoubtable that hypothermia can be used as a means of controlling the persistent increased ICP.Citation21 However, we also have to pay much more attention to prevent adverse effects of hypothermia in sTBI patients, such as infection, pulmonary embolism, coagulation disturbances, rebound increase in ICP, and decreased oxygenation of hypoxic areas.Citation22–Citation24 All of these effects may counteract the neuroprotective effects of hypothermia therapy.

Hypertonic dehydration, such as the application of mannitol, is commonly used as an initial treatment for the management of raised ICP after sTBI.Citation25 A study in the UK showed that 100% of neurosurgical centers used mannitol in the treatment of raised ICP.Citation26,Citation27 Mannitol is effective in reducing ICP in the management of traumatic intracranial hypertension and carries mortality benefit compared to barbiturates.Citation28 Although international guidance about the dosage of mannitol is from 0.25 g/kg to 1 g/kg,Citation29,Citation30 there is no uniform dosage for clinical application for dehydration. In this study, we compared the efficiency of two different doses (25 g and 50 g) of mannitol by monitoring ICP in the condition of mild hypothermia. We found that two doses of mannitol had the same efficiency on ICP in the early stage, but the high dosage of mannitol was better than the low one in maintaining stability in the drug effect time. The same result that high-dose mannitol may be preferable to conventional-dose mannitol in the acute management of comatose patients with severe head injury has been reported in another study.Citation31

The treatment of 26 sTBI patients with DC showed their ICP decreased significantly. A series of brain parameters of CPP, PbtO2, and SjvO2 suggested that the DC treatment could benefit by controlling ICP and improving intracranial blood flow and oxygen supply. DC for the treatment of sTBI has a long history, but it is still more complicated and more controversial about its clinical effect. Depending on the research status around the world, the DC therapeutics is the only second-line method for refractory high ICP. The application standards and surgical protocol of DC are still uncertain. Craniectomy is certainly effective in reducing ICP and is lifesaving in patients with sTBI,Citation32 but many questions remain regarding its ideal application, and the outcome remains highly correlated with the severity of the initial injury, such as infection of incisional wound, diffuse brain swelling, increased prevalence of posttraumatic epilepsy, skin flap dropsy in the surgical site, and aggravated postoperative primary injury.Citation33,Citation34

For the sTBI patients who had no clinical effects after therapies of hypothermia and hypertonic dehydration, we adjusted the ventilator breathing patterns and performed hyperventilation to assist ICP. The result showed that ICP improvement tended to be obvious followed by hyperventilation under the condition of mild hypothermia, but subsequently, it is possible to cause low PbtO2. It suggested that the hyperventilation in MHT could temporarily decrease ICP but may accompany some disadvantages such as PbtO2 decline and brain anoxia. There are many clinical practices of hyperventilation that had the same concerns.Citation35–Citation37 Hyperventilation lowers ICP by the induction of cerebral vasoconstriction with a subsequent decrease in cerebral blood volume.Citation38 The downside of hyperventilation, however, is that cerebral vasoconstriction may decrease cerebral blood flow to ischemic levels. Hyperventilation in the treatment of sTBI must be carefully performed. PbtO2 and other oxygenation parameters have to be frequently monitored at the same time to avoid anoxia. Based on the practice of monitoring brain situation with multiparameters, our opinion is to use hyperventilation for the short-term control of raised ICP in sTBI patients, but multimodality monitoring has to be performed simultaneously in order to safely target hyperventilation therapy to specific patients who may benefit from this therapy.

In spite of development of a lot of advanced techniques for sTBI treatment, such as stem cell-based and nanotechnology-based therapies and physical and pharmaceutical interventions,Citation39 monitoring of brain parameters and observation of change in vital signs in the process of MHT combined with conventional therapies are extremely necessary.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MurrayGTeasdaleGBraakmanRThe European brain injury consortium survey of head injuriesActa Neurochir1999141322323610214478

- LangEWPittsLHDamronSLRutledgeROutcome after severe head injury: an analysis of prediction based upon comparison of neural network versus logistic regression analysisNeurol Res19971932742809192380

- MarshallLFGautilleTKlauberMRThe outcome of severe closed head injuryJ Neurosurg1991751SS28S36 Special Supplements

- SmithMMonitoring intracranial pressure in traumatic brain injuryAnesth Analg2008106124024818165584

- CliftonGLJiangJYLyethBGJenkinsLWHammRJHayesRLMarked protection by moderate hypothermia after experimental traumatic brain injuryJ Cereb Blood Flow Metab19911111141211983995

- BramlettHMGreenEJDietrichWDBustoRGlobusMY-TGinsbergMDPosttraumatic brain hypothermia provides protection from sensorimotor and cognitive behavioral deficitsJ Neurotrauma19951232892987473803

- ArcureJHarrisonEA review of the use of early hypothermia in the treatment of traumatic brain injuriesJ Spec Oper Med200893222519739473

- BustoRGlobusMDietrichWDMartinezEValdesIGinsbergMDEffect of mild hypothermia on ischemia-induced release of neurotransmitters and free fatty acids in rat brainStroke19892079049102568705

- BeringEAEffect of body temperature change on cerebral oxygen consumption of the intact monkeyAm J Physiol Legacy Content19612003417419

- SmithSLHallEDMild pre-and posttraumatic hypothermia attenuates blood-brain barrier damage following controlled cortical impact injury in the ratJ Neurotrauma1996131198714857

- BouzatPFranconyGOddoMPayenJTherapeutic hypothermia for severe traumatic brain injuryAnn Fr Anesth Reanim20133211787791 French24138767

- SunHTChengSXTuYWuHCLiZLZhangSClinical significant and changes of brain tissue partial pressure of oxygen in the course of mild hypothermia with severe traumatic brain injuryChin J Neurosurg2012282141144

- BiswasBAdhyaSWashartPBacteriophage therapy rescues mice bacteremic from a clinical isolate of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faeciumInfect Immun200270120421011748184

- PoldermanKHJoeRTTPeerdemanSMVandertopWPGirbesAREffects of therapeutic hypothermia on intracranial pressure and outcome in patients with severe head injuryIntensive Care Med200228111563157312415442

- TokutomiTMiyagiTTakeuchiYKarukayaTKatsukiHShigemoriMEffect of 35 C hypothermia on intracranial pressure and clinical outcome in patients with severe traumatic brain injuryJ Trauma200966116617319131820

- HutchisonJSFrndovaHLoT-YGuerguerianA-MHypothermia Pediatric Head Injury Trial InvestigatorsCanadian Critical Care Trials GroupImpact of hypotension and low cerebral perfusion pressure on outcomes in children treated with hypothermia therapy following severe traumatic brain injury: a post hoc analysis of the Hypothermia Pediatric Head Injury TrialDev Neurosci2011325–640641221252486

- DarwazehRYanYMild hypothermia as a treatment for central nervous system injuries: positive or negative effectsNeural Regen Res2013828267725206579

- InamasuJIchikizakiKMild hypothermia in neurologic emergency: an updateAnn Emerg Med200240222023012140503

- HarrisOAColfordJMJrGoodMCMatzPGThe role of hypothermia in the management of severe brain injury: a meta-analysisArch Neurol20025971077108312117354

- DietrichWDAtkinsCMBramlettHMProtection in animal models of brain and spinal cord injury with mild to moderate hypothermiaJ Neurotrauma200926330131219245308

- YangSYZhangCDomestic and foreign hypothermia treatment for severe traumatic brain injuryChin J Neurosurg201026112

- RundgrenMEngströmMA thromboelastometric evaluation of the effects of hypothermia on the coagulation systemAnesth Analg200810751465146818931200

- FinkelsteinRAAlamHBInduced hypothermia for trauma: current research and practiceJ Intensive Care Med201025420522620444735

- OddoMFrangosSMaloney-WilenskyEKofkeWALe RouxPDLevineJMEffect of shivering on brain tissue oxygenation during induced normothermia in patients with severe brain injuryNeurocrit Care2010121101619821062

- HarutjunyanLHolzCRiegerAMenzelMGrondSSoukupJEfficiency of 7.2% hypertonic saline hydroxyethyl starch 200/0.5 versus mannitol 15% in the treatment of increased intracranial pressure in neurosurgical patients – a randomized clinical trial [ISRCTN62699180]Crit Care200595R53016277715

- JeevaratnamDMenonDSurvey of intensive care of severely head injured patients in the United KingdomBMJ199631270369449478616307

- MattaBMenonDSevere head injury in the United Kingdom and Ireland: a survey of practice and implications for managementCrit Care Med19962410174317488874315

- MangatHSHärtlRHypertonic saline for the management of raised intracranial pressure after severe traumatic brain injuryAnn N Y Acad Sci20151345838825726965

- ShigemoriMAbeTArugaTGuidelines for the Management of Severe Head Injury, 2nd Edition guidelines from the Guidelines Committee on the Management of Severe Head Injury, the Japan Society of NeurotraumatologyNeurol Med Chir2012521130

- BrainTFGuidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. MethodsJ Neurotrauma200724Suppl 1S317511542

- WakaiARobertsISchierhoutGMannitol for acute traumatic brain injuryCochrane Database Syst Rev20138CD00104923918314

- YangSYEfficacy evaluation of hemicraniectomy in treatment of traumatic brain injuryChin J Trauma2011273197200

- FlintACManleyGTGeanADHemphillJC3rdRosenthalGPost-operative expansion of hemorrhagic contusions after unilateral decompressive hemicraniectomy in severe traumatic brain injuryJ Neurotrauma200825550351218346002

- ZhangCTuYZhaoMLClinical significance of large decompressive craniectomy to control intractable increased intracranial pressure in patients with traumatic brain injuryChin J Neurosurg2011272169173

- OertelMKellyDFLeeJHEfficacy of hyperventilation, blood pressure elevation, and metabolic suppression therapy in controlling intracranial pressure after head injuryJ Neurosurg20029751045105312450025

- NeumannJ-OChambersICiterioGThe use of hyperventilation therapy after traumatic brain injury in Europe: an analysis of the BrainIT databaseIntensive Care Med20083491676168218449528

- KetySSSchmidtCFThe effects of active and passive hyperventilation on cerebral blood flow, cerebral oxygen consumption, cardiac output, and blood pressure of normal young menJ Clin Invest1946251107

- StocchettiNMaasAIChieregatoAvan der PlasAAHyperventilation in head injury: a reviewChest J2005127518121827

- ReisCWangYAkyolOWhat’s new in traumatic brain injury: update on tracking, monitoring and treatmentInt J Mol Sci2015166119031196526016501