Abstract

The aim of the present study was to assess the occurrence and predictive factors of sleep paralysis (SP) in Czech university students. Our sample included 606 students who had experienced at least one episode of SP. The participants completed an online battery of questionnaires involving questionnaires focused on describing their sleep habits and SP episodes, the 18-item Boundary Questionnaire (BQ-18), the Modified Tellegen Absorption Scale (MODTAS), the Dissociative Experience Scale Taxon, the Beck Depression Inventory II and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. The strongest predictive factor for the frequency of SP episodes was nightmares. The strongest predictive factor for the intensity of fear was dream occurrences. In our study sample, SP was more common in women than in men. Those who scored higher in BQ-18 experienced more often pleasant episodes of SP and those who scored higher in MODTAS were more likely to experience SP accompanied with hallucinations. While 62% of respondents answered that their SP was accompanied by intense fear, 16% reported that they experienced pleasant feelings during SP episodes. We suggest that not only the known rapid eye movement sleep dysregulation but also some personality variables may contribute to the characteristics of SP.

Introduction

Isolated sleep paralysis (SP) is a recurrent inability to move the body at sleep onset or upon awakening from sleep lasting seconds to a few minutes. The episodes cause clinically significant distress. The episodes cannot be better explained by another sleep disorder, mental disorder, medical condition, medication, or substance use.Citation1

The etiology is not known yet. SP mostly occurs in young adulthood, but there is a lifetime prevalence.Citation2,Citation3 Almost 8% of general population, 28% of students and 32% of psychiatric patients experience at least one episode of SP during their lives.Citation2 The sooner the SP begins, the more frequent the episodes are.Citation4

Experiencing SP is usually unpleasant. Fear has been reported in 90% of the student sample.Citation5 In psychiatric outpatients, the clinically significant level of fear was found in 69% of cases.Citation6 According to Cheyne,Citation7 fear arises mostly from the reaction to an inability to move or the hallucinatory content. Approximately 70% of SP episodes are accompanied by hallucinations,Citation8,Citation9 although some studies found their simultaneous occurrence only in 33%.Citation10 Mostly, we distinguish 3 types of hallucinations – intruders, incubus and vestibular–motor hallucinations. Incubus and intruder hallucinations are correlated with each other and with intense fear. Vestibular–motor hallucinations can be associated with blissful and erotic feelings.Citation11,Citation12

The aim of our study was to assess the occurrence and predictive factors of SP in Czech university students. We were especially interested whether personality traits play a role in the frequency of SP rather than external factors such as irregular sleep patterns, sleep deprivation and stressful events.

Methods

The study was designed as a cross-sectional questionnaire-based descriptive study and was carried out from February 2015 to June 2015. The study sample consisted of Czech undergraduate and postgraduate students who answered to an advertisement for the study in university social media. All of them participated voluntarily and anonymously. Our criteria for inclusion were to have experienced SP at least once (“Have you ever experienced a transitional state of inability to move accompanied by hallucinations, when you can’t move or scream, during falling asleep or waking up?”) and currently being the student in present or distant form of study in undergraduate or postgraduate university level. We excluded those participants who did not fill out the whole questionnaire battery and those who answered that they suffer from another sleep disorder. We did not exclude participants with psychiatric disorders, due to our interest in the connection between SP with anxiety and depressive states. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The study was approved by the Ethic Commission of National Institute of Mental Health and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Instrumental tools

We used a battery of questionnaires divided into 6 parts. We designed a questionnaire to determine the participant’s sleep habits (the length of sleep during workdays and on weekends, the amount of sleep they need to feel refreshed, presence and frequency of dreams and nightmares). Regarding the SP episodes, we asked for their age at the time of first occurrence, frequency and duration of episode, daytime occurrence, type of hallucinations, sleeping posture, factors that helped to stop the episode, intensity of fear and pleasantness of episodes.

The 18-item Boundary Questionnaire (BQ-18)

The BQ-18 is a short version of the Boundary Questionnaire,Citation13 a self-administered questionnaire to measure boundaries of personality. Total score ranges from 0 to 64. The higher the score is, the thinner the boundaries are. People with thin boundaries have a blurred distinction between all aspects of their lives and are open in many ways. People with thick boundaries are solid, well-defended and have a clear distinction in all aspects of their lives.Citation14

The Modified Tellegen Absorption Scale (MODTAS)

JamiesonCitation15 modified the original Tellegen Absorption Scale (TAS). Absorption is a latent personality construct, initially described by Tellegen and AtkinsonCitation16 as a

Disposition for having episodes of ‘total’ attention that fully engage someone’s representational (ie, perceptual, enactive, imaginative, and ideational) resources.Citation16

The total score ranges from 0 to 136. The higher the score is, the higher the ability of absorption the people have.

The Dissociative Experience Scale Taxon (DES-T)

DES-TCitation17,Citation18 is an 8-item subscale version of the full-scale DES developed by Bernstein and Putman in 1986.Citation19 The DES-T measures pathological dissociation. DES-T consists of 8 statements (descriptions of situations), and the subjects should indicate how often they experience the described situations (0%, 10%, 20%, … 100%). Total scores are calculated by averaging the score in the 8 items. Higher scores indicate higher degree of dissociation. Dissociation occurs to some degree in normal populations.Citation17 Bernstein and PutmanCitation19 described dissociation as “the lack of normal integration of thoughts, feelings, and experiences into the stream of consciousness and memory”.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

STAICitation20 is a 40-item scale to measure anxiety. It consists of 2 parts – the first part (STAI-S) evaluates the current state of anxiety, ie, how the participants feel now. The second part (STAI-T) measures anxiety as a personality trait, ie, stable individual differences in anxiety proneness including general state of calmness and confidence. The score range for each subtest is from 20 to 80. Higher scores indicate greater anxiety.Citation21

Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI II)

BDI II is an improved form of BDI developed by Beck et al in 1961.Citation22 BDI II is a 21-item inventory to measure depressive symptoms. The answers are chosen from 4 options ranging from 0 (not present) to 3 (severe). Total score ranges from 0 to 63; the higher the score, the more severe the signs of depression are.Citation23

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, we used χ2 tests for nominal variables with a significance level of 0.05. The Mann–Whitney U-test was conducted to compare frequency of SP episodes between genders. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to compute the strength of relationship between frequency of SP (or intensity of fear) and scores of questionnaires or other ordinal data. t-Test for independent samples was performed to compare questionnaire scores of group with or without pleasant feelings in SP or hallucinations. A multinomial logistic regression analysis was used to find factors affecting the frequency of SP and the intensity of fear. For the need of logistic regression analysis, we connected 6 levels of frequency and 5 levels of intensity of fear into groups frequent/not frequent and fearful/not fearful. Statistical analyses were conducted in STATISTICA Version 12 and IBM SPSS Statistics 23.

Results

The study sample consisted of 1,351 undergraduate and postgraduate students, 606 of them met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Of them, 169 (28%) were men and 437 (72%) women. Mean age of the sample was 23.3 years (SD =2.9 years). A total of 17 participants were diagnosed with psychiatric disorder (depression [n=5], anxiety [n=6], combination of depression and anxiety [n=2], eating disorder [n=1], panic disorder [n=1], bipolar disorder [n=1] and combination of social phobia and panic disorder [n=1]).

The most represented fields of studies in our sample were social sciences (n=191; 32%), followed by natural sciences (n=84; 16%), technical sciences (n=55; 9%), medical sciences (n=45; 7%), art schools (n=42; 7%) and others and combinations (n=42; 7%). A total of 42% (n=147) of the participants did not answer the question about their field of study.

The mean age of the first SP episode was 17 years, and 24% (n=146) of participants experienced SP episodes before the age of 15 years. SP was more common in women than in men (z=2.28; P=0.036). The most frequent SP duration was between few seconds and 2 minutes (n=324; 54%); shorter episodes were referred to in 22% of the sample (n=133). A total of 20% of participants reported episodes between 2 and 5 minutes (n=120) and 5% (n=28) referred to episodes longer than 5 minutes. The SP episodes typically occurred in the supine position (n=383; 63%) rather than in the lateral position (n=143; 24%), prone position (n=50; 8%) or others (n=30; 5%). A familial form of SP was present in 6% of participants. A total of 83% (n=502) of our respondents reported that their SP episodes were always characterized by a complete inability to move, typically accompanied by hallucinations (n=475; 78%). The most common was a combination of different sensory modalities (44% cases). The most typical kind of hallucination was visual (11%), followed by auditory (4%) and feelings of the sensed presence (4%).

In most cases, SP occurred several times a year (n=225; 37%). SP occurred less than a few times a year in 199 cases (33%) and only 2 participants reported daily episodes. SP mostly occurred throughout the night (n=212; 35%), less frequently during sleep onset (n=175; 29%), around morning awakening (n=130; 21%) or during daytime naps (n=89; 15%).

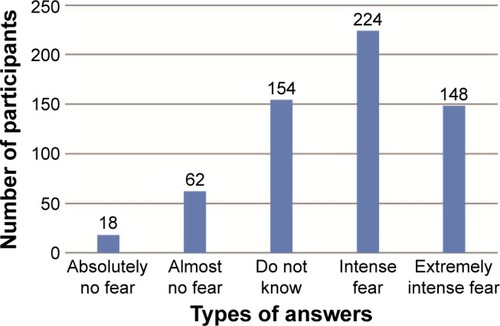

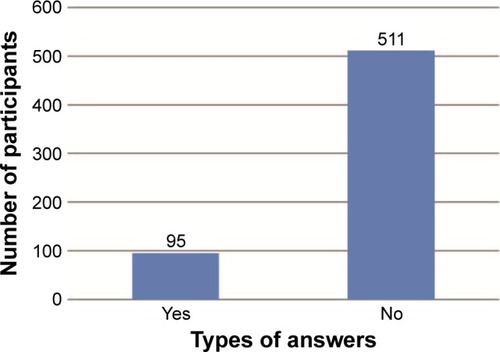

SP is generally regarded as a frightening event (), but our results also show frequent pleasant episodes (n=95, 16%; ). A total of 40% (n=245) of participants were able to define a trigger (stressful events 23%, lack of sleep 9%, fatigue 4%, watching TV and horrors 2%, daytime naps 2% and the full moon 2%) to their SP episodes. According to our respondents, SP episodes typically terminated spontaneously (48%, n=292) or by intense effort to move (38%, n=228).

After fulfilling the criteria for χ2 tests, we calculated Spearman’s rank correlation. There were 2 correlations found between the frequency of SP and scores in questionnaires (r=0.092 and 0.082, respectively). Although their values are low, the test considered them as significant and confirmed that the score in DES-T and the score in STAI-S were positively associated with more frequent SP episodes. Correlations between other questionnaires and the frequency of SP were not significant. Using χ2 tests and Spearman’s rank correlations, no significant relationships were found between the frequency of SP and the form or study program, sleep duration, dream occurrence, timing of episodes, inability to move and the length of the SP episodes. Intensity of fear was not correlated with the questionnaire scores. We found higher BQ-18 score in subjects experiencing pleasant SP (t=3.44; P<0.001). A significant difference was found in the score of MODTAS for SP accompanied by hallucinations (t=2.435; P=0.015).

Based on the results of χ2 tests with a significance level of 0.05, we conducted multinomial logistic regression analysis to find predictive factors of the frequency of SP () and the intensity of fear (). The strongest predictive factor for the SP frequency was nightmares (odds ratio [OR] =1.56; P=0.019), and a protective factor was the male gender (OR =0.52; P=0.001). The strongest predictive factor for the intensity of fear was the sleep with recalled dreams, many dreams and a few dreams, respectively (OR =3.98; P=0.003 and OR =3.95; P=0.004).

Table 1 Predictive factors of the frequency of sleep paralysis

Table 2 Predictive factors of the intensity of fear

Discussion

According to our results, most common SP experience in university students was only several times a year, which corresponds with the assumed distribution of SP in general population and with the presumption that SP is quite a common phenomenon in its isolated form, although the recurrent experience is rare. In our study, SP occurred more often in women than men, as shown similarly in previous studies;Citation2 however, this result cannot be conclusively interpreted because more women participated in the study.

We found that the mean age at the time of the first SP occurrence was 17 years and 24% of respondents stated that SP started even before the age of 15 years. We suggest that SP in university students is not the result of actual irregular sleep patterns or sleep deprivation, which is common in this population.Citation24 The age of onset of SP corresponds to the age of the beginning of narcolepsyCitation25 and could be related to antecedent rapid eye movement (REM) sleep dysregulation.

Another interesting finding is that most of our participants reported a SP occurrence throughout the night. Current scientific literature provides inconsistent results with respect to typical timing of SP episodes. SP episodes have been reported to be more prevalent at sleep onset,Citation26 during the first 2 hours after sleep onsetCitation27 as well as at sleep offset.Citation3 In the study by Cheyne,Citation7 the most frequent timing was a combination of time (beginning of sleep, middle of the night and end of sleep). This discrepancy might be partially due to methods of questioning about the timing of SP episodes. For example, when questioning only about the timing of SP episodes either while falling asleep or while waking up,Citation26 waking up could be in the morning or in the middle of the night.

SP is typically connected with unpleasant feelings and fear.Citation1 Accordingly, 69% of our participants answered that SP was accompanied by intense or extreme fear, whereas only 3% experienced absolutely no fear (). We found that predictive factors for the intensity of fear had the presence of dreams, the inability to move, hallucinations and occurrence of SP in the middle of the night. According to Cheyne’s hypothesis,Citation7 the intensity of hallucinations in SP could be stronger in the middle of the night and in the morning hours. We would expect that the intensity of hallucinations would predict fear related to SP episodes not only in the middle of the night but also in the morning hours.

Interestingly, we found that 16% of our participants also experienced pleasant feelings during SP episodes () that were rarely mentioned earlier.Citation4,Citation28 Parker and BlackmoreCitation28 found that 2% of women and 8% of men experienced happiness during their SP episodes. According to Cheyne,Citation4 pleasant feelings could be positively associated with vestibular–motor hallucinations. Our data show that participants who describe SP as pleasant have thinner boundaries, which means that they are open to new experiences. These participants are more creative with rich fantasies and are more affected by external and internal stimuli including dreams, which tend to be more bizarre too.Citation14,Citation29,Citation30 We suggest that the positive content of SP episodes and high frequency of dreams might be used in psychotherapy for SP.

Using a multinomial logistic regression analysis, the strongest predictive factor for the frequency of SP seems to be the presence of nightmares. According to Hall and Van de Castle,Citation31 positive emotions are usually mentioned in only one-third of dream reports and two-thirds of emotions are described as unpleasant. Nightmares are connected with unpleasant feelings. When nightmares are looked at only from the emotional aspect, the quality of emotions experienced during nightmares is very similar to that experienced during SP episodes. Fear is dominant in both the states. Parker and BlackmoreCitation28 found that women reported SP as more fearful, felt more victimized and experienced more sexual activity. Kotorii et alCitation32 found also a strong correlation between SP and dreams and nightmares. However, our results did not show a significant correlation between the SP frequency and fear intensity.

McNally and ClancyCitation9 using DES Questionnaire and Absorption Scale in their study showed that people who experience SP score higher on DES and Absorption scale than those who have not experienced SP. WatsonCitation33 found a positive correlation between dissociative score and nightmares, dying in a dream, sensing someone around, flying dreams, hypnopompic and hypnagogic imagery. Similarly, we found a positive correlation between score on DES-T and the frequency of SP episodes. We have not seen a significant relationship between MODTAS, BQ-18 and STAI-T and the frequency of SP.

Although students are thought to be one of the most likely populations to experience SP, our limitations to this population could lead to misrepresenting the results, because SP can occur at any age. We only used self-administered questionnaires that could also misrepresent the results, for example, due to an altered self-image or the social desirability effect. We did not have a control group, so we cannot compare our results of participants who experienced SP with those who did not experience it. Our study design was retrospective, which could influence the data. Further studies should focus on the pleasant aspects of SP and the psychotherapy of SP.

Conclusion

In our sample of 606 university students, we found that SP is more frequent in women and occurs mostly several times a year. The strongest predictive factor for the frequency of SP episodes is nightmares. A total of 69% of respondents reported that SP was accompanied by intense or extreme fear, but 16% reported that they experienced pleasant feelings during episodes of SP. The strongest predictive factor for the intensity of fear is the occurrence of dreams. People who score higher in BQ-18 Questionnaire experience more often pleasant feelings during SP episodes. People who score higher in MODTAS experience more frequently SP episodes with hallucinations.

We suggest that not only the known REM sleep dysregulation influences SP but also some personality variables may contribute to the characteristics of SP.

Acknowledgments

This study is a result of the research funded by the project Nr. LO1611 with a financial support from the MEYS under the NPU I program. This publication was supported by the project “National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH-CZ)” grant number ED2.1.00/03.0078 and the European Regional Development Fund. This publication was further supported by the project “PRVOUK P34”.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- American Academy of Sleep MedicineInternational Classification of Sleep DisordersDarien, ILAmerican Academy of Sleep Medicine2014

- SharplessBABarberJPLifetime prevalence rates of sleep paralysis: a systematic reviewSleep Med Rev201115531131521571556

- OhayonMMZulleyJGuilleminaultCSmirneSPrevalence and pathologic associations of sleep paralysis in the general populationNeurology19995261194120010214743

- CheyneJASleep paralysis episode frequency and number, types, and structure of associated hallucinationsJ Sleep Res200514331932416120108

- CheyneJANewby-ClarkIRRuefferSDRelations among hypnagogic and hypnopompic experiences associated with sleep paralysisJ Sleep Res19998431331710646172

- SharplessBAMcCarthyKSChamblessDLMilrodBLKhalsaSRBarberJPIsolated sleep paralysis and fearful isolated sleep paralysis in outpatients with panic attacksJ Clin Psychol201066121292130620715166

- CheyneJASituational factors affecting sleep paralysis and associated hallucinations: position and timing effectsJ Sleep Res200211216917712028482

- Jimenez-GenchiAAvila-RodriguezVMSanchez-RojasFTerrezBENenclares-PortocarreroASleep paralysis in adolescents: the ‘a dead body climbed on top of me’ phenomenon in MexicoPsychiatry Clin Neurosci200963454654919496997

- McNallyRJClancySASleep paralysis, sexual abuse, and space alien abductionTranscult Psychiatry200542111312215881271

- JalalBHintonDERates and characteristics of sleep paralysis in the general population of Denmark and EgyptCult Med Psychiatry201337353454823884906

- CheyneJARuefferSDNewby-ClarkIRHypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations during sleep paralysis: neurological and cultural construction of the night-mareConscious Cogn19998331933710487786

- CheyneJAThe ominous numinous – sensed presence and ‘other’ hallucinationsJ Conscious Stud200185–7133150

- HartmannEBoundaries of dreams, boundaries of dreamers: thin and thick boundaries as a new personality measurePsychiatr J Univ Ott19891445575602813637

- KunzendorfRGHartmannECohenRCutlerJBizarreness of the dreams and daydreams reported by individuals with thin and thick boundariesDreaming199774265

- JamiesonGThe modified Tellegen absorption scale: a clearer window on the structure and meaning of absorptionAust J Clin Exp Hypn200533119139

- TellegenAAtkinsonGOpenness to absorbing and self-altering experiences (“absorption”), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibilityJ Abnorm Psychol19748332682774844914

- WallerNGPutnamFWCarlsonEBTypes of dissociation and dissociative types: a taxometric analysis of dissociative experiencesPsychol Methods199613300321

- WallerNGRossCAThe prevalence and biometric structure of pathological dissociation in the general population: taxometric and behavior genetic findingsJ Abnorm Psychol199710644995109358680

- BernsteinEMPutnamFWDevelopment, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scaleJ Nerv Ment Dis1986174127277353783140

- SpielbergerCDGorsuchRState-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults: Manual and Sample: Manual, Instrument and Scoring GuidePalo Alto, CAConsulting Psychologists Press1983

- JulianLJMeasures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A)Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken)201163suppl 11S467S47222588767

- BeckATWardCHMendelsonMMockJErbaughJAn inventory for measuring depressionArch Gen Psychiatry1961456157113688369

- BeckASteerRBrownGManual for the BDI-IISan Antonio, TXPsychological Corporation1996

- BrandSKirovRSleep and its importance in adolescence and in common adolescent somatic and psychiatric conditionsInt J Gen Med2011442544221731894

- KotagalSNarcolepsy in childrenSemin Pediatr Neurol19963136438795840

- SpanosNPMcnultySADubreuilSCPiresMBurgessMFThe frequency and correlates of sleep paralysis in a university sampleJ Res Pers1995293285305

- GirardTACheyneJATiming of spontaneous sleep-paralysis episodesJ Sleep Res200615222222916704578

- ParkerJDBlackmoreSJComparing the content of sleep paralysis and dream reportsDreaming20021214559

- HartmannEHarrisonRZborowskiMBoundaries in the mind: past research and future directionsN Am J Psychol200133347368

- ReinselRAntrobusJWollmanMWaking fantasyThe Neuropsychology of Sleep and Dreaming1992157184

- HallCSVan de CastleRLThe Content Analysis of DreamsNew York, NYAppleton-Century-Crofts1966

- KotoriiTKotoriiTUchimuraNQuestionnaire relating to sleep paralysisPsychiatry Clin Neurosci200155326526611422869

- WatsonDDissociations of the night: individual differences in sleep-related experiences and their relation to dissociation and schizotypyJ Abnorm Psychol2001110452653511727942