Abstract

Background

Methylphenidate (MPH) has been found to be an effective medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). However, there are neither consistent nor sufficient findings on whether psychiatric comorbidities and associated cognitive functions of ADHD are related to treatment response to MPH in ADHD children.

Objectives

This study investigated whether psychiatric comorbidities, IQ, and neurocognitive deficits are related to treatment response to MPH in ADHD children. In some ways, it is preferable to have a drug that the effectiveness of which to a disorder is not affected by its associated cognitive functions and psychiatric comorbidities. On the other hand, it is likely that the baseline symptom severity of ADHD is associated with the effectiveness of MPH treatment on the symptoms post treatment.

Methods

A total of 149 Chinese boys (aged 6–12 years) with ADHD, combined type, and normal IQ participated in this study. Assessment of ADHD symptom severity was conducted pre and post MPH treatment, while assessment of psychiatric comorbidities, IQ, and neurocognitive deficits was performed in a non-medicated condition. Treatment response was defined as the ADHD symptom severity post MPH treatment.

Results

Results indicated that MPH treatment was effective, significantly improving the ADHD condition. Yet, comorbid disorders, IQ, and neurocognitive deficits were not related to MPH treatment response on ADHD symptoms. These findings indicated that the effectiveness of MPH was not affected by psychiatric comorbidities and associated cognitive functions of ADHD. Instead, as expected, it was the baseline symptom severity that was mainly related to the treatment response, ie, the milder the baseline condition, the better the treatment response.

Conclusion

The current findings positively endorse the widespread clinical use of MPH for treating ADHD. It improves the behavioral symptoms of ADHD regardless of varying psychiatric comorbidities, IQ, and neurocognitive deficits.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by inattention (IA), hyperactivity, and impulsivity, incurring considerable learning and psychosocial impairments. It is among the most prevalent neuropsychiatric disorders affecting 5%–10% of children worldwide.Citation1 Despite that existing stimulant treatment (primarily by methylphenidate, MPH) falls short of a cure to eradicate ADHD, it remains the most efficacious treatment for short-term symptomatic relief of ADHD with effect sizes ranging from 0.78 to 0.96.Citation2,Citation3 Yet, it is also known that there is individual variation in response to MPH among ADHD children with a minority, up to 20%–30%, reporting milder or little improvement.Citation4 Unfortunately, there are neither consistent nor sufficient findings on conditions differentiating responsiveness to MPH in ADHD children. In this study, a comprehensive range of such potential conditions was examined.

Psychiatric comorbidities of ADHD

Anxiety

Initial studies found that response to MPH would be poorer among ADHD children with anxiety.Citation5,Citation6 There was suspicion that ADHD with comorbid anxiety might be different from that without.Citation7 The inattentive behavior of the former might actually be secondary to anxiety. However, recent studies reported that comorbid anxiety made no difference to the effectiveness of MPH with ADHD.Citation8,Citation9

Depressive disorders

Studies found inconsistent results regarding comorbid depressive disorders on treatment response to MPH with ADHD. Yet once again, recent studies seemed to support that ADHD with or without comorbid depressive symptoms equally benefited from MPH.Citation10,Citation11

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD)

Quite a number of studies found that ADHD children with or without comorbid ODD/CD responded equally well to MPH.Citation8,Citation12 One study found that ADHD children with comorbid aggressive behaviors responded better to MPH.Citation6 However, the study itself explained that the better response might be due to inflated rating consequential to halo effects brought upon by improvement in disruptive and oppositional behaviors.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

The few studies available found that ADHD children with or without ASD responded equally well to MPH.Citation13,Citation14

Cognitive functions

IQ

Available studies showed that ADHD children with mental retardation did not respond well to MPH.Citation15,Citation16 However, MPH was equally effective for ADHD children whose IQs were within the normal range.Citation17 It was reasoned that ADHD with mental retardation might represent a qualitatively different type of the disorder than that with normal intelligence.Citation18

Specific learning difficulties

The impact of comorbid specific learning difficulties on treatment response to MPH in ADHD children has been scarcely studied. Available literature indicated that they were not related to treatment response to MPH.Citation19

Neurocognitive deficits

There are a number of neurocognitive deficits identified to be associated with ADHD, namely response disinhibition, interference control dysfunction, delay aversion, poor working memory, time estimation errors, and deficient sustained attention. However, their relationship to treatment response to MPH is rarely studied. The few studies that were available showed inconsistent findings. Response disinhibition was related to poorer treatment response to MPH in ADHD children, while interference control dysfunction was not related to any differences in MPH treatment response.Citation20,Citation21 Given such scanty literature, it is difficult to conclude whether ADHD-associated neurocognitive deficits are related to treatment response to MPH in ADHD children.

Objectives

Given the existing inconsistent and limited findings, there is no strong evidence to conclude either way as to whether psychiatric comorbidities and associated cognitive functions are related to treatment response to MPH in ADHD children. The current study aimed at reexamining this question, including a wide range of psychiatric comorbidities and cognitive functions. In some ways, it is preferable to have a drug that the effectiveness of which to a disorder is not affected by its associated cognitive functions and frequent psychiatric comorbidities. The lack of such relationships should be welcomed by clinicians who find the drug (MPH) equally beneficial to ADHD children with diverse psychiatric comorbidities and cognitive functions. On the other hand, it is likely that the baseline symptom severity of the disorder (ADHD) is associated with the effectiveness of MPH in alleviating the symptoms post treatment.

Methods

Participants

The sample was recruited from boys attending a child psychiatric clinic in Hong Kong between January 2013 and September 2015 who were clinically diagnosed with ADHD (combined type) by psychiatrists, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).Citation22 The current study recruited only boys because of the high gender ratio of boys to girls with ADHD presented in child psychiatric clinics.Citation23 The number of girls might still be too small even within a reasonably sized sample of over 100 for data analysis in a scientifically acceptable way. Additional inclusion criteria were Chinese ethnicity, aged 6–12 years, and studying in local mainstream primary schools. Exclusion criteria were IQ below 80, bipolar disorder, psychosis, autism, severe obsessive–compulsive disorder, Tourette’s syndrome or chronic serious tics, birth injury, head trauma, or major causative genetic, neurological, metabolic, or infectious illnesses.

Measures

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – fourth edition (Hong Kong) (WISC-IV [HK])

It is a test of intelligence for children with local norms for Hong Kong. Four subtests, the scores of which had been found to be highly correlated with the full-scale IQ, were administered, ie, similarities, digit span, matrix reasoning, and coding.Citation24

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children – fourth edition (parent-informant) (P-DISC-IV)

It is a structured diagnostic interview with parents as informants and is administered by trained personnel. It examines more than 30 common child psychiatric disorders. P-DISC-IV was well validated as a diagnostic tool with both clinical and community samples.Citation25 It generates categorical diagnoses as well as dimensional symptom scores (criterion counts).

Chinese version of the Autism Spectrum Quotient – 10 items (child version) (Chinese AQ-10-Child)

The Chinese AQ-10-Child is a parent-report questionnaire for assessing autistic features in children. It is an abbreviated version of the 50-item Autism Spectrum Quotient (child version). It had been found to show high sensitivity and specificity in screening ASD.Citation26

Hong Kong Test of Specific Learning Difficulties in Reading and Writing for Primary School Students – second edition (HKT-P[II])

It is a test of specific learning difficulties for Cantonese- speaking children with local norms for Hong Kong. The HKT-P(II) had reported satisfactory psychometric properties.Citation27

The stop-signal task

It is a computerized reaction time task of response inhibition. Participants are required to withhold a response by not pressing a key if a tone is sounded in a particular trial. The measure reflecting participants’ capability of response inhibition is called “stop-signal reaction time (SSRT)”. It estimates how long it takes for a participant to inhibit a response. Stop-signal task had demonstrated satisfactory validity in differentiating between ADHD children and normal controls.Citation28

The Stroop color–word task (computerized version)

It is a task of interference control. An interference score, Golden interference score,Citation29 measures the participants’ ability to suppress a prepotent or habitual response.

Within-subject variability in reaction time in the Stroop color–word task is regarded as a measure assessing sustained attention. It is operationalized as within-subject standard deviation of reaction time (SD-RT) and coefficient of variation (CV). A larger SD-RT and CV indicate a greater variability in responses, reflecting a difficulty in sustaining attention to maintain a constant speed to respond. The SD-RT was found to show high sensitivity and specificity in discriminating ADHD individuals from normal controls.Citation30

The Maudsley Index of Childhood Delay Aversion (MIDA)

It is an index indicating delay aversion in children with ADHD. Participants are required to make a choice between a smaller immediate reward, ie, a shorter-sooner (SS) response, earning 1 point if they only choose to wait for 2 seconds, or a larger delayed reward, ie, a larger-later (LL) response, earning 2 points if they instead choose to wait for 30 seconds. There are two experimental conditions: one with a post reward delay and one without. MIDA was found to be significantly related to ADHD.Citation31

Digit Span subtest of WISC-IV (HK)

It is used to examine working memory of the participants. Children with ADHD had been found to perform significantly poorer in the Digit Span subtest when compared to normal controls.Citation32

Time estimation task

This task assesses participants’ ability to accurately estimate the length of different time intervals randomly presented to them, namely 6, 12, 36, and 60 seconds. An absolute discrepancy (AD) score is computed, which is the absolute difference between participants’ estimated time and actual time presented to them.Citation33

Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD Symptoms and Normal Behaviors Rating Scale (SWAN) (parent-informant)

It is a parent-report questionnaire that has been revalidated in Hong Kong and provides rating of the 18 key ADHD features on children.Citation34 A lower score represents a severer ADHD condition. In this study, the SWAN provides assessment of the baseline symptom severity of ADHD pre MPH treatment as well as the treatment response to MPH (indexed by the post MPH treatment SWAN score). This definition of treatment response is commonly used in previous studies, including the landmark Multimodal Treatment of ADHD (MTA) study in the USA.Citation14,Citation35

Procedures

The psychiatrists at their regular consultation sessions determined the clinic attendants who matched the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. For those who met the former and not the latter, invitation was made to their parents to participate in the study. Written informed consent was provided by the parents of the participants for this study. This study obtained ethics approval from relevant institutional boards, namely Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong – New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee and Kowloon West Cluster Research Ethics Committee.

All clinic attendants referred to our child psychiatric clinic would be asked to fill in a number of questionnaires, including SWAN, when they came to their first consultation session. For the ADHD boys recruited to participate in our study, those SWAN records were taken as assessing the baseline pre-MPH treatment ADHD symptom severity. The ADHD boys were then arranged to undergo testing on IQ, neurocognitive deficits, and specific learning difficulties. The participants’ parents served as informants to the DISC-IV. The assessment with one ADHD participant and one of his parents as an informant required separately 2–3 hours each. Despite efforts to schedule the assessment sessions as soon as possible, they might still take a month or two to arrange, since local children had usually a very busy schedule, given full-day schooling, heavy homework, and a very competitive examination system. However, since MPH was considered the first-line treatment of ADHD in Hong Kong, it would be prescribed even at the first consultation once the case psychiatrists had clinically established the ADHD diagnosis. Therefore, despite that a sizable portion of our participants were new referrals, they were likely to be on MPH treatment when assessment sessions were finally scheduled. To have baseline assessment of their cognitive functions unaffected by medication, all ADHD participants were required to be medication free for at least 48 hours prior to the testing.

All participants in this study received MPH treatment for their ADHD condition. Based upon the case psychiatrists’ clinical expertise, some participants (53%) in our study were prescribed multiple-dose, immediate-release MPH, namely Ritalin, while some other participants were prescribed a single-dose, extended-release MPH, namely Concerta or Ritalin long-acting (LA) (16.8% and 10.7%, respectively). The remaining participants (19.5%) were prescribed both Concerta and Ritalin or Ritalin and Ritalin LA. The dosages from Concerta and Ritalin LA were converted into dosage units of Ritalin for data compilation according to an international standard.Citation36 In sum, the dosage of all participants ranged from 10 to 60 mg per day (Ritalin; mean =23.43; SD =9.48). Specifically, 87.9% of the participants (n=131) were prescribed 10–30 mg of MPH per day, while only 12.1% of the participants (n=18) were prescribed over 30 mg per day.

SWAN was readministered as the outcome measure of treatment response after at least 12 weeks of continual MPH treatment. This 12-week period was considered to be of sufficient duration to allow proper titration for all participants, based upon the clinical judgment of the case psychiatrists at regular follow-ups. No other form of treatment was concurrently received by the participants.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Baseline ADHD symptom severity was predicted to be related to treatment response to MPH so that it would be treated as a covariate in analysis (analyses of covariance [ANCOVA] or partial correlation) examining the relationship between psychiatric comorbidities/cognitive functions and treatment response. The latter was operationalized in this study as the post MPH treatment SWAN score. The abovementioned analysis would be followed by regression analysis, entering those significantly related independent variables to build a prediction model.

Results

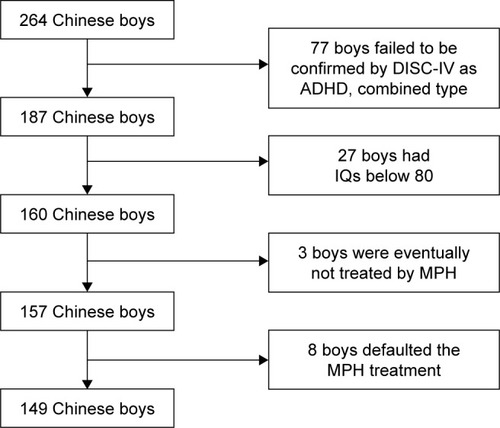

A total of 264 clinically diagnosed ADHD boys of Chinese ethnicity were recruited into the study. Among them, the clinical diagnosis of 77 children failed to be confirmed by DISC-IV as ADHD, combined type. Many of these 77 children were instead diagnosed by DISC-IV as either the IA or hyperactivity–impulsivity (HI) type of ADHD. This lack of perfect agreement between clinical diagnosis and DISC-IV diagnosis was not entirely unexpected, given the known moderate inter-rater reliability of psychiatric diagnosis. The loss of sample size was compensated by an increased confidence on the diagnostic identity of our ADHD participants. A total of 27 children were further excluded because of IQs below 80. Of the 160 children who were eligible for this study, three children were eventually not treated by MPH. Eight children defaulted the MPH treatment at various time points during the 12-week titration period. The final sample of this study was thus composed of 149 boys. depicts graphically the multiple steps in arriving at our final sample.

Figure 1 Flowchart of recruitment of participants.

There was a significant difference between pre and post MPH treatment SWAN scores, indicating a positive treatment effect of MPH (mean =44.7, SD =11.8 vs mean =69.8, SD =17.3, t[148]=17.57, Cohen’s d=1.50). As predicted, there was a significant correlation between pre and post MPH treatment SWAN scores; milder baseline ADHD symptom severity was associated with better treatment response on ADHD symptoms post MPH treatment (r=0.34; P<0.001). In view of space limitation, descriptive statistics of other variables (mean and SD) are not reported in this study, but can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

The psychiatric comorbidities tested included social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, selective mutism, obsessive–compulsive disorder, specific phobia, major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, ODD, and CD. Panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and post traumatic stress disorder were assessed but not tested, since no ADHD children had obtained such diagnoses from DISC-IV. Since many individual diagnoses had small numbers, they were collapsed into broader diagnostic groupings, namely any anxiety disorder (including all anxiety disorders assessed in DISC-IV), any depressive disorder (including major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder), any disruptive disorder (including ODD and CD), and any psychiatric disorder (including all DISC-IV diagnoses tested). These broader groupings gave more balanced ratios between those ADHD children with some of these comorbidities and those without. There was uniformly no significant difference in treatment response between groups with or without various comorbidities ().

Table 1 ADHD symptoms (SWAN) post MPH treatment between groups with and without psychiatric comorbidities (N=149)

Dimensional analysis by partial correlation (controlling baseline ADHD symptom severity) between DISC-IV criterion counts of various comorbidities and post MPH treatment SWAN score was also performed and found the same insignificant results. The correlation coefficients were uniformly very small (<0.15, most even at <0.10; ). The comorbidities tested included not only all DISC-IV diagnoses mentioned earlier but also specific learning difficulties and ASD symptoms, whose measures provide dimensional scores. Broad diagnostic groupings were again created by summing the criterion count of each disorder after proration. However, the same lack of significant correlation with very small coefficients was found (<0.10; ).

Table 2 Partial correlation of ADHD symptoms post MPH treatment with psychiatric comorbidities, controlling baseline ADHD symptoms (N=149)

There was also no significant partial correlation between ADHD symptoms (SWAN) post MPH treatment and associated cognitive functions, after partialing out the baseline ADHD symptom severity ( and ). The correlation coefficients were again very small (<0.15, most even at <0.10). The cognitive functions tested included single or multiple indices of IQ, response disinhibition, interference control dysfunction, deficient sustained attention, poor working memory, delay aversion, and time estimation errors.

Table 3A Partial correlation of ADHD symptoms post MPH treatment with IQ, response disinhibition (stop-signal task), inter ference control dysfunction (Stroop task), and deficient sustained attention (Stroop task), controlling baseline ADHD symptoms (N=149)

Table 3B Partial correlation of ADHD symptoms post MPH treatment with delay aversion (MIDA task), time estimation errors (time estimation task) and poor working memory (Digit Span of WISC-IV [HK]), controlling baseline ADHD symptoms (N=149)

Multiple regression was not run to build a prediction model, since no independent variable was found to be correlated with treatment response to MPH in ADHD symptoms.

Discussion

All psychiatric comorbidities of ADHD tested in this study, including individual disorders and broader diagnostic groupings, were not related to treatment response to MPH in ADHD symptoms. The lack of such relationship is consistent with the literature regarding comorbid specific learning difficulties and ASD. In this study, we must note that those children with a clinical diagnosis of ASD have already been excluded from inclusion. However, a minority of the ADHD participants (10%) still scores above the clinical cutoff of AQ. Hence, our current sample can still provide some range of ASD symptoms to test how their presence affects the ADHD outcome of MPH treatment.

On the other hand, some previous studies do suggest that comorbid anxiety, depression, and ODD/CD may affect the degree of benefits from MPH treatment. However, it must be noted that as a whole, existing evidence supporting these findings is neither strong nor consistent. More recent studies with comorbid anxiety and depression seem to suggest that ADHD children with or without these comorbidities equally benefit from MPH. Although one study does find improved response to MPH by ADHD children with aggressive behavior, it reasons that the improvement is mainly due to inflated rating influenced by halo effects.Citation6 Expectedly, existing studies differ from each other in terms of research designs, measures, definitions of disorders or treatment response, samples, etc. It cannot be easily concluded whether these differences may explain some of the inconsistent findings. More studies are probably required in the future to see the dominant trend of findings emerging from studies of diverse methodologies and populations.

Consistent with the existing literature that IQ within the normal range is not related to treatment response to MPH in ADHD symptoms,Citation17 our study with participants having IQ of 80 or above shows a similar finding.

Response disinhibition, interference control dysfunction, poor working memory, delay aversion, time estimation errors, and deficient sustained attention are identified neurocognitive deficits of ADHD. All of their measures administered in a non-medicated condition in the current study are not related to treatment response to MPH in ADHD symptoms. Given the very limited existing studies noted earlier, it is hard to decide whether our current findings are to be expected or not. Once again, more replication studies are called for.

Besides behavioral symptoms, MPH has also been found to improve neurocognitive functioning, such as sustained attention and working memory,Citation37 and normalize the malfunctioned brain regions associated with ADHD, eg, increasing the activities of frontal and striato-thalamic regions.Citation38 On the other hand, ADHD behavioral symptoms and neurocognitive deficits may not be causally related to each other directly.Citation39 Changes in neurocognitive functioning do not necessarily bring corresponding changes in behavioral symptoms of ADHD or vice versa. In other words, baseline non-medicated neurocognitive functioning may be related to improvement in its own domain post MPH treatment, but not necessarily to behavioral improvement in ADHD symptoms, as measured by our outcome measure, SWAN. In future studies, a fairer examination of the relationship between baseline neurocognitive deficits and MPH treatment response is to have measures of neurocognitive outcomes post MPH treatment. However, for informing clinical practice, changes in behavioral symptoms remain the primary concern for clinicians. This explains why this study chooses to concentrate on behavioral symptoms of ADHD rather than its neurocognitive functioning.

Limitations and future direction

First, this study does not pretend to be a clinical trial; it has not adopted the standard methodology of a randomized controlled trial (RCT). There are neither standardized dosages nor duration of treatment for the ADHD participants. Instead, it is a naturalistic clinic study with boys who attended a child psychiatric clinic for routine treatment of their ADHD condition. The case psychiatrists use their clinical expertise to determine the optimal MPH treatment for each boy. The only condition that this study imposes on the ADHD treatment is to allow the psychiatrists at least 12 weeks to identify the optimal dosage before post MPH treatment SWAN is administered to determine the treatment response. We take this clinic ADHD treatment to examine whether psychiatric comorbidities and non-medicated cognitive functions of ADHD can predict treatment response to MPH in ADHD symptoms. The behavioral improvement that we see from the clinical practice of MPH medication is encouraging, but we will not claim this finding a formal evaluation of the efficacy of MPH without conducting a well-controlled RCT. Our reported improvement on ADHD condition post MPH treatment should not be interpreted as such. Nonetheless, a large effect size of improvement should not be considered as unexpected, given converging evidence of repeated meta-analyses from many previous well-controlled clinical trials.Citation2,Citation3 It is less likely that the treatment response is an artifact resulting from regression-to-mean, maturation, or a learning effect from repeated assessment, etc.

The current study included participants who are boys aged 6–12 years with IQ of 80 or above and ADHD, combined type. The results of this study may not be generalizable to ADHD girls or to ADHD boys with other types of ADHD (ie, IA or HI), with ages before 6 years or beyond 12 years, or with IQ below 80. The same concern applies to ADHD children with a range of psychiatric comorbidities excluded from this study (our exclusion criteria are stated earlier). In addition, our coverage of conditions potentially influencing MPH treatment response is not exhaustive. For example, negative self-concept was recently found to be a predictor of poorer treatment responsiveness to MPH.Citation40 Future research should expand to cover the aforementioned untested conditions.

This study used a parent-report measure, SWAN, for assessing treatment response. Having multiple informants may be desirable to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the ADHD behaviors under assessment. We should also consider assessing functioning and behaviors other than those primary symptoms of ADHD, such as social or academic functioning, as treatment responses in future study.

Last but not least, there is so far limited knowledge about the underlying pharmacological mechanism of MPH. This makes our current study explorative rather than theoretically driven. We may have to wait for more knowledge about the therapeutic mechanism of MPH before we can have a more informed choice of conditions to be tested as related to treatment response to MPH. Nonetheless, the current findings imply that the drug action of MPH seems to be quite exclusively related to ADHD. Its effectiveness does not seem to be dependent on or in interaction with those frequent psychiatric comorbidities and associated cognitive functions of ADHD. Thus, it is not surprising to find the baseline ADHD symptom severity as the only condition correlated with the treatment response to MPH in ADHD children.

Conclusion and clinical implication

This study has its strength and contribution. It covers a more comprehensive list of potential conditions to be related to response to MPH treatment in ADHD children than those of many previous studies. Some of our tested conditions, such as neurocognitive deficits, have been rarely studied and some have previously produced inconsistent findings. Our study is also reasonably sized with 149 well-defined children with ADHD, combined type. The results have also been very uniform with the group comparison and correlation consistently insignificant with small coefficients across all clinical and cognitive conditions tested. This is so despite a large number of statistical tests having been conducted and this may have caused concern of chance findings if significant results did emerge.

The lack of relationship between treatment response to MPH and psychiatric comorbidities/associated cognitive functions in fact positively endorses the widespread clinical use of MPH for treating ADHD. It improves the behavioral symptoms of ADHD regardless of varying psychiatric comorbidities and associated cognitive functions. Given the clinical reality of high frequencies of psychiatric comorbidities and neurocognitive deficits with ADHD, clinicians are pleased to learn that they do not affect the clinical effectiveness of MPH. For example, at one time, studies seem to suggest that MPH treatment is not effective for ADHD children with comorbid anxiety. However, this study joins the more recent findings indicating that comorbid anxiety makes no difference to the effectiveness of MPH treatment to ADHD. Given this growing literature, clinicians can confidently prescribe MPH to ADHD children with comorbid anxiety so that they can also reap the therapeutic benefits of MPH.

Acknowledgments

This study is funded by a General Research Fund (GRF) grant to the corresponding author, Patrick WL Leung, from the Research Grants Council (RGC), Hong Kong (RGC 449511).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- SwansonJMSergeantJATaylorEASonuga-BarkeEJSJensenPSCastellanosFXAttention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderPfaffDWVolkowNDNeuroscience in the 21st CenturyNew York, NYSpringer Science + Business Media2016218

- FaraoneSVGlattSJA comparison of the efficacy of medications for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using meta-analysis of effect sizesJ Clin Psychiatry201071675476320051220

- LeuchtSHierlSKisslingWDoldMDavisJMPutting the efficacy of psychiatric and general medicine medication into perspective: review of meta-analysesBr J Psychiatry201220029710622297588

- SchachterHMPhamBKingJLangfordSMoherDHow efficacious and safe is short-acting methylphenidate for the treatment of attention deficit disorder in children and adolescents? A meta-analysisCMAJ2001165111475148811762571

- MosheKKarniATiroshEAnxiety and methylphenidate in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a double-blind placebo-drug trialAtten Defic Hyperact Disord20124315315822622628

- Ter-StepanianMGrizenkoNZappitelliMJooberRClinical response to methylphenidate in children diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbid psychiatric disordersCan J Psychiatry201055530531220482957

- GoezHBack-BennetOZelnikNDifferential stimulant response on attention in children with comorbid anxiety and oppositional defiant disorderJ Child Neurol200722553854217690058

- JensenPSHinshawSPKraemerHCADHD comorbidity findings from the MTA study: comparing comorbid subgroupsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200140214715811211363

- AbikoffHMcGoughJVitielloBRUPP ADHD/Anxiety Study GroupSequential pharmacotherapy for children with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity and anxiety disordersJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200544541842715843763

- DuPaulGJBarkleyRAMcMurrayMBResponse of children with ADHD to methylphenidate: interaction with internalizing symptomsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19943368949038083147

- GadowKDNolanEESverdJSprafkinJSchwartzJAnxiety and depression symptoms and response to methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and tic disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol200222326727412006897

- PliszkaSThe effects of anxiety on cognition, behavior, and stimulant response in ADHDJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19892868828872808258

- SantoshPJBairdGPityaratstianNTavareEGringrasPImpact of comorbid autism spectrum disorders on stimulant response in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a retrospective and prospective effectiveness studyChild Care Health Dev200632557558316919137

- HandenBLJohnsonCRLubetskyMEfficacy of methylphenidate among children with autism and symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorderJ Autism Dev Disord200030324525511055460

- AmanMGBuicanBArnoldLEMethylphenidate treatment in children with borderline IQ and mental retardation: analysis of three aggregated studiesJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol2003131294012804124

- PearsonDALaneDMSantosCWEffects of methylphenidate treatment in children with mental retardation and ADHD: individual variation in medication responseJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443668669815167085

- EfronDJarmanFBarkerMMethylphenidate versus dextroamphetamine in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a double-blind, crossover trialPediatrics19971006E6

- RutterMMacdonaldHLe CouteurAHarringtonRBoltonPBaileyAGenetic factors in child psychiatric disorders – II. Empirical findingsJ Child Psychol Psychiatry199031139832179248

- TannockRIckowiczASchacharRDifferential effects of methylphenidate on working memory in ADHD children with and without comorbid anxietyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19953478868967649959

- ScheresAOosterlaanJSergeantJASpeed of inhibition predicts teacher-rated methylphenidate response in boys with AD/HDInt J Disabil Dev Educ200653193109

- van der OordSGeurtsHMPrinsPJEmmelkampPMOosterlaanJPrepotent response inhibition predicts treatment outcome in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorderChild Neuropsychol2012181506121819279

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th ed text revWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- GraetzBWSawyerMGHazellPLArneyFBaghurstPValidity of DSM-IV ADHD subtypes in a nationally representative sample of Australian children and adolescentsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200140121410140711765286

- WechslerDWechsler Intelligence Scale for Children4th ed short formHong Kong, ChinaKing-May Psychological Assessment2010

- ShafferDFisherPLucasCPDulcanMKSchwab-StoneMENIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnosesJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2000391283810638065

- AllisonCAuyeungBBaron-CohenSToward brief “Red Flags” for autism screening: the short autism spectrum quotient and the short quantitative checklist in 1,000 cases and 3,000 controlsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry201251220221222265366

- HoCSHChanDWTsangSLeeSThe Hong Kong Test of Specific Learning Difficulties in Reading and Writing (HKT-SpLD) ManualHong KongHong Kong Specific Learning Difficulties Research Team2007

- OosterlaanJLoganGDSergeantJAResponse inhibition in AD/HD, CD, comorbid AD/HDCD, anxious, and control children: a meta-analysis of studies with the stop taskJ Child Psychol Psychiatry19983934114259670096

- GoldenCStroop Color and Word Test: A Manual for Clinical and Experimental UsesChicago, ILStoelting1978

- UebelHAlbrechtBAshersonPPerformance variability, impulsivity errors and the impact of incentives as gender-independent endophenotypes for ADHDJ Child Psychol Psychiatry201051221021819929943

- PaloyelisYAshersonPKuntsiJAre ADHD symptoms associated with delay aversion or choice impulsivity? A general population studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200948883784619564796

- MayesSDCalhounSLLearning, attention, writing, and processing speed in typical children and children with ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, and oppositional-defiant disorderChild Neuropsychol200713646949317852125

- HuiJSense of Time and Delay Aversion in Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) [Unpublished master’s thesis]Hong KongDepartment of Psychology, Chinese University of Hong Kong2007

- ChanGFCLaiKYCLukESLHungSFLeungPWLClinical utility of the Chinese strengths and weaknesses of ADHD-symptoms and normal-behaviors questionnaire (SWAN) when compared with DISC-IVNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2014101533154225187717

- OwensEBHinshawSPKraemerHCWhich treatment for whom with ADHD? Moderators of treatment response in the MTAJ Consult Clin Psychol200371354055212795577

- U.S. Food and Drug AdministrationFull prescribing information for Concerta2010 Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021121s026s027lbl.pdfAccessed January 27, 2017

- AgayNYechiamECarmelZLevkovitzYMethylphenidate enhances cognitive performance in adults with poor baseline capacities regardless of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosisJ Clin Psychopharmacol201434226126524525641

- PaulsAMO’DalyOGRubiaKRiedelWJWilliamsSCMehtaMAMethylphenidate effects on prefrontal functioning during attentionalcapture and response inhibitionBiol Psychiatry201272214214922552046

- CoghillDRHaywardDRhodesSMGrimmerCMatthewsKA longitudinal examination of neuropsychological and clinical functioning in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Improvements in executive functioning do not explain clinical improvementPsychol Med20144451087109923866120

- SayGNKarabekirogluKYuceMFactors related to methylphenidate response in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a retrospective studyDüşünen Adam2015284319327