Abstract

The relationship between parents and infants born preterm is multifaceted and could present some relational patterns which are believed to predict psychological risk more than others. For example, insensitive parenting behavior has been shown to place very preterm children at greater risk of emotional and behavioral dysregulation. The main objective of this study was to compare the quality of family interactions in a sample of families with preterm children with one of the families with at-term children, exploring possible differences and similarities. The second aim of this research was to consider the associations among family interactions and parental empowerment, the child’s temperament, parenting stress, and perceived social support. The sample consisted of 52 children and their families: 25 families, one with two preterm brothers with preterm children (mean 22.3 months, SD 12.17), and 26 families with children born at term (mean 22.2 months, SD 14.97). The Lausanne Trilogue Play procedure was administered to the two groups to assess the quality of their family interactions. The preterm group was also administered the Questionari Italiani del Temperamento, the Family Empowerment Scale, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form. Differences in the quality of family interactions emerged between the preterm and at-term groups. The preterm group showed significantly lower quality of family interactions than the at-term group. The parenting stress of both parents related to their parental empowerment, and maternal stress was also related to the partner’s parental empowerment. Social support had a positive influence on parenting stress, with maternal stress also related to perceived social support from the partner, which underscores the protective role of the father on the dyad.

Introduction

The World Health Organization classifies prematurity based on gestational age (GA) as extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28<GA<32 weeks), and moderate–late preterm (>32–<37 weeks).Citation1 Preterm birth rates are increasing in almost all countries with reliable data.Citation1 In Italy, the latest report from the Ministry of Health (published in 2012) discusses data collected in 2008, when the percentages of babies born before the 37th and before the 32nd week of gestation were 6.8% and 0.9%, respectively.Citation2

The immaturity of preterm newborns exposes them to multiple, complex medical problems that demand a lengthy stay in neonatal intensive care units. The stress and painful procedures of this unphysiological extrauterine environment affect the immature nervous system of preterm newborns, giving rise to a different trajectory in their neurobehavioral developmentCitation3,Citation4 and a greater risk of disorders later on.Citation5,Citation6

The existing literature has explored the preterm child’s development in depth. Studies report cognitive impairments, namely, a lower IQ than term-born children,Citation5,Citation7–Citation9 even when they are within the normal range.Citation10,Citation11 The difference depends on their GA at birth:Citation7,Citation12 their IQ declines by a mean 2.5 points for every week’s decrease in GA, starting from the 33rd week.Citation7 Executive functions, attention, and linguistic and communicative skills are other areas of weaknessCitation13–Citation20 not explained by a general cognitive deficit.

According to studies that have considered motor development, preterm children whose intelligence is within the normal range could still encounter gross and fine motor delaysCitation8 that interfere with their exploration of the environment, writing abilities, and involvement in social activities, becoming a risk factor for future cognitive and learning abilities and for behavioral problems.Citation21

On the subject of their behavioral and emotional development, preterm infants may show weak relational, emotional, and social competence; difficult self-regulation of behavior and emotions; and a limited attention span already in the early stages of their development.Citation22 Their impaired social skills negatively affect their socialization ability and their capacity to handle peer relationships. It is also worth noting that most studies have reported that very preterm children show higher mean scores on socioemotional scales than their term-born peers, though not reaching clinical cutoff scores.Citation6 As for the temperament construct, an Italian sample of 105 children (mean age 5 years and 2 months) born before the 32nd week of gestation showed a mainly normal profile for the Italian culture, but they also revealed some peculiarities: apart from positive emotionality (where they scored significantly higher than children born at term), the preterm group showed lower levels of motor control and attention, negative emotional reactivity and social orientation, and inhibition to novelty, although the differences in their scores did not reach statistical significance.Citation23

Another aspect examined in the literature is parental distress, given the stressful experience and concern for their child’s health and the fact that preterm delivery interrupts the transition to parenthood. The mother’s psychological suffering has been studied more, but more attention has recently been paid to the father because of his stronger involvement in the event of premature birth.Citation24,Citation25

Immediately after a preterm birth, 40% of mothers show symptoms of postpartum depression, as opposed to 10%–15% of mothers giving birth at term,Citation26 and they generally suffer from postpartum stress.Citation27 State anxiety is also higher after a preterm birth, due to the mother’s persistent and continuous apprehension for the health of their child, perceived as vulnerable.Citation28 Even in the case of late prematurity (at 32–37 weeks of gestation), the mothers of preterm infants display higher levels of depression and anxiety than the mothers of infants born at term when assessed 6 months after the delivery, whereas this was not the case 2 months after the delivery.Citation29

Mothers’ psychological stress is often associated with some degree of comorbidity. Shaw et alCitation30 found that 77.8% of preterm infants’ mothers had at least one symptom attributable to depression,Citation31–Citation33 anxiety,Citation34 or post-traumatic syndrome,Citation35,Citation36 and 51% had symptoms attributable to at least two of these conditions. Given the strong emotional experience in the period of transition to parenthood, some authors have focused on assessing the stress related to parenting. When parenting stress was assessed with the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (PSI-SF)Citation37 in mothers of 12-month-old children (corrected age), those whose offspring were born prematurely experienced twice as much stress as the mothers of those born at term. The difference emerged mainly on parent–infant dysfunctional interaction, suggesting that mothers of preterm babies had more difficulty in connecting to their child.Citation38 Olafsen et alCitation39 discovered a deep association between parenting stress and negative reactive temperament in 1-year-old children.

Research has found that parents’ psychological distress can show determinant effects on infants and children, including impaired parent–infant interaction quality,Citation40,Citation41 which can in turn result in different consequences on infant development, such as behavioral dysregulation and impaired language, cognitive, and motor development.Citation41–Citation43 In particular, the relationship between child and parents is paramount in providing the foundation for self-regulation capacities and for both relational–affective and cognitive development.Citation44,Citation45 In fact, infant cognitive development appears to be related to parent–infant interactions, in particular to parent sensitivity and touch, from the parent’s ability to verbalize infant affective states; these parental interactive skills can all be exacerbated by distress.Citation43,Citation46–Citation48 Santos et alCitation49 found that mothers under extreme psychological distress displayed more positive involvement and cognitive stimulation, in order to compensate for the lack of interactive behavior from a sick or at-risk infant.Citation50 A recent study of Montirosso et alCitation50 found differential brain activation patterns in mothers of preterm children. With regard to fathers, 10% (versus 20% of mothers) met the criteria for an adjustment disorder and had more severe symptoms of anxiety,Citation34 depression,Citation51 and post-traumatic syndrome, which appeared later in fathers (4 months after their child’s birth, they were more at risk than the mothers). This could be because the father needs to concentrate initially on sustaining the mother, who is more fragile and vulnerable in the early period after the birth.Citation36

Despite this evidence, these aspects have been less examined in the literature from a triadic point of view. Infant medical risk may compound the effects of a preterm birth on parental and infant functioning and the quality of parent–infant interaction. In such situations, social support is a protective factor for both parents’ well-being and mental health, since it can reduce the parents’ stress.Citation53–Citation55 Actually, mean values for perceived social support of “preterm parents” have been found to be 5 points higher than “at-term parents”, underscoring its importance in the case of high-level stress.Citation54 Singer et alCitation55 also found that the extremely stressful conditions relating to the preterm birth do not decrease the adults’ self-perception of competence as parents.

In this regard, family empowerment has been identified as an important indicator in families with at-risk children,Citation56,Citation57 but it has been studied less in families with preterm children, in particular after parents leaving the neonatal intensive care unit. Given the aforementioned intrinsic risk factors involving the parents and their child, some studies have focused on the parent–preterm child relationship, specifically exploring the interaction. Prematurity has a negative influence on interactive, communicative, and expressive mother–child behaviors during the first years of life.Citation58,Citation59

As a party in this interaction, the preterm child is seen as more passive,Citation60–Citation62 less alert and focused,Citation62,Citation63 and less responsive.Citation64–Citation66 They are less inclined to make eye contact with their motherCitation67–Citation69 and may be less vocal,Citation66,Citation70 or more vocal,Citation71 but with less contingency.Citation64 They have less well-developed self-regulatory competence,Citation72 smile less,Citation73 and are generally characterized by the expression of more negative affectCitation62,Citation67,Citation74,Citation75 than infants born at term. According to some studies, preterm infants also find it more difficult to give clear clues to caregivers.Citation76,Citation77

In this context, concerning maternal behavior, studies have generally found that the maternal interactive style is more directive, active, and controlling at 3 months,Citation60,Citation63,Citation70,Citation71 and mothers tend to be less sensitive,Citation60,Citation70 using a directive scaffoldingCitation78,Citation79 with a contradictory style alternating passive and overstimulating exchanges.Citation80

As for preterm parenting behavior, so far studies have generated inconsistent and contradictory results,Citation58,Citation59 possibly due in part to the tools used to assess interactions and to the heterogeneity of the samples considered.Citation81 Some studies found parents of preterm infants to be sensitive and responsive,Citation68,Citation74,Citation82 but tending to express responsiveness verbally more than in their facial expressions.Citation71 They use social monitoring and eye contactCitation81 and positive affect expressed verbally and nonverbally,Citation72 although birth weight influences the intrusiveness of mothers.Citation81

In summary, the literature has identified a particular interactive style in preterm dyads, characterized by more passive exchanges with few infant initiatives. Some authors attribute this characteristic to maternal intrusiveness, while others state that such maternal intrusiveness represents in truth greater reactivity aimed at compensating for the child’s developmental inadequacy.Citation58,Citation69 A recent study found that the experience of joint attention did not lead to positive developmental outcomes when the child was not actively involved.Citation18

With regard to affection, while studies involving a heterogeneous group of preterm children found no differences,Citation72,Citation74 other research observed that children were born extremely preterm and their mothers mainly expressed neutral emotions during interactive exchanges.Citation18 Finally, some authors have made the point that certain aspects characteristic of interaction with preterm children become gradually clearer after the first 6 months of the child’s life, when the environment becomes more complex and demanding.Citation65,Citation70,Citation74,Citation83 Feldman and EidelmanCitation76 also pointed out that a mother’s postpartum interactive behavior predicts both maternal and paternal future interactive synchrony with their child.

As for the father’s role, few studies have observed father strategies of interaction with the preterm child. As in the case of the mother, this interaction is of poorer quality than when a child is born at term.Citation84 There is less dyadic reciprocity, and the parent has more difficulty adapting to the child’s timing and rhythms,Citation85 with fewer moments of joint attentionCitation86 and less eye contact synchrony.Citation76 Although many authors recommend assessing triadic interaction in families with children born preterm,Citation18,Citation87,Citation88 few studies have adopted a method for observing the triad in interactions. Higher levels of rigidity and lower levels of cohesion have been found in families with very low-birth-weight or intrauterine growth restriction children compared to control families.Citation85 Only one recent study used the Lausanne Trilogue Play (LTP),Citation89 the observational method selected for the purposes of the present research. In that study, only seven variables (regarding affect sharing, timing/synchronization, and child behavior) of the LTP were used to examine the interaction in 83 families with 6-month-old healthy children born between the 28th and 34th weeks of gestation,Citation90 and no differences emerged from comparison with a normative group. This interesting study is one of the few published in the literature to have investigated the moderating role of family dynamics in the development of preterm children. It was also the first to use the LTP approach to assess this construct. The study only partially considered family interactions, though, because they were not the main focus of the study. It thus seems worthwhile to explore triadic interactions after the first 6 months of life, given that there are reports in the literature of differences subsequently emerging in the dyadic interactive style of parents and their preterm child.

Our literature review brought to light the shortage of specific studies on the role of family interactions in the preterm child’s development. The effect of distress on parent–children interactions, as well as the importance of social support and family empowerment as mediators, has been discharged, but still little has been deepened at the level of parent–child interactions; furthermore, fathers have been little involved as the focus of study. The family is the primary child’s context of socialization, and empirical research has shown that family interactions are predictive of several child development outcomes. Given these reasons, research on an at-risk population needs to be extended, and this is the specific area that our study aimed to approach.

Aims

This paper aims to contribute to the literature on family interactions in families with children born preterm. To date, no sufficient literature has observed the quality of such family interactions as a whole. The literature has concentrated more on certain components, such as parental scaffolding or affect sharing, thereby diminishing the importance of a more global observation. The first aim of the present work was consequently to observe the quality of family interactions by extending the method applied in the study by Gueron-Sela et al,Citation90 using all the LTP variables for the purpose of further elucidating the impact of family interactions on the child’s development. We thus applied the LTP to a sample of families with children born preterm, comparing the results with those obtained in a group of families with children born at term. In this comparison, we expected to find differences in some variables of the LTP, specifically in child involvement and parental capacities in engaging the child during interactions. Given the fact that these variables could counterbalance each other, we also anticipated to find no differences in terms of global quality of family interactions, as suggested by Gueron-Sela et al.Citation90

The second aim of the present study was to investigate in the preterm group the parents’ self-perception of their parental empowerment, level of parenting stress, and perceived social support, in order to observe the influence of these constructs on the quality of family interactions. We hypothesized a strong association between low quality of family interactions and low parental empowerment, high level of parenting stress, and low level of perceived social support.

As observed in a previous study,Citation91 which emphasized the importance of child factors, child’s interactive abilities may contribute to an improvement of family interaction quality. In this study, we set out to observe the influence of the child’s temperament on the perception of parenting stress and family empowerment and consequently on the quality of family interactions. We hypothesized that difficult temperament qualities were expected to be correlated with low quality of family interactions, low parental empowerment, and high level of parenting stress. As emerged from previous studies,Citation92,Citation93 the preterm group was found to be more affected by the quality of early caregiving than the normative group, suggesting that both researchers and clinicians should exploit the opportunities afforded by the observation of family interactions in cases of prematurity.Citation90 Our study aimed to contribute to filling this gap by sketching some pictures of the dynamics involved.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

The total sample consisted of 52 children with their families. The preterm group comprised 26 children (mean 22.3 months, SD 12.17). Families were recruited from two Italian organizations that offer support and intervention for preterm children and their families: a private Onlus association, Pulcino, and the Neurorehabilitation Service, forming part of the Unit for Children, Adolescents, and Families of the Public Health Service Unità Locale Socio Sanitaria (ULSS) in Padua. Families attending the Neurorehabilitation Service were recruited by a child neuropsychiatrist, who explained the purpose of the project and placed them in contact with the people responsible for this research project. Families in Pulcino were recruited by the association, which explained the purpose of the project, and (subject to family consent) placed them in contact with the people responsible. The LTP procedure and test battery were administered at the Unit for Children, Adolescents, and Families for all families.

All parents taking part in the project signed informed consent for the study, which was approved by the ethical committee of the ULSS 16 of Padua (CEP 204 SC). The control group employed in this study was part of a longitudinal study on the development of family interactions.Citation94 This project involved a hundred couples who had spontaneously conceived their first child and were followed up from the seventh month of pregnancy until their child was 48 months old. A group of 26 children (mean 22.2 months, SD 14.97) and their families was drawn from this sample, to match the preterm group in terms of the child’s age and sex and the parents’ ages.

The LTP procedureCitation89 was administered to the two groups of families to assess the quality of their family interactions. The group with preterm children was also administered the following questionnaires: the Questionari Italiani del Temperamento,Citation95 the Family Empowerment Scale (FES),Citation96 the PSI-SF,Citation37 and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.Citation97 shows the characteristics of the two groups.

Table 1 Descriptive analysis of the groups of families with children born preterm and at term

Materials

The following materials were selected from the literature to answer to our specific research questions.

Lausanne Trilogue Play

The LTP is a specific semistandardized procedure that observes the quality of parent–child interactions in a play observational situation.Citation89 The play is divided into four parts corresponding to the four possible interactive configurations. In part 1, one of the two parents interacts with the child while the other stays simply present (configuration 2+1). In part 2, the parents’ roles are reversed (configuration 2+1). In part 3, both parents interact together with the child (configuration 3). In part 4, the parents talk together while the child remains an observer (configuration 2+1). Three chairs forming an equilateral triangle compose the specific setting (a high chair is adapted to the age of the child).

The procedure was coded according to the Family Alliance Assessment Scale 4.0 (unpublished manual, Centre d’Etude de la Famille [CEF] 2006). Scores range from 1 (inappropriate) to 3 (appropriate) for 10 variables, according to the frequency and duration of interactive behaviors. Scores were attributed to each variable for each of the four separate parts and also computed together (total range 60–180). Two trained independent judges coded the videotapes of this research, achieving a Cohen’s κ-value of 0.9.

Questionari Italiani del Temperamento

This is an Italian self-report questionnaire that aims to assess a child’s temperament in four age ranges.Citation95 For the present study, the questionnaires for children aged 1–12 months, 13–36 months, and 3–6 years were used, which consist of 55, 56, and 60 items, respectively, and are divided into six subscales: social orientation, inhibition to novelty, motor control activity, attention, positive emotionality, and negative emotionality. The questionnaire can be answered by parents (even with a low–medium formal education), educators/teachers, or anyone taking care of the child and spending time with them every day, so that the respondent can think about the child in three different contexts (child with others, child playing alone, child dealing with novelty or while performing an activity or a task). Answers are given on a Likert scale ranging from “almost never” (1) to “almost always” (6).

Family Empowerment Scale

The FES is a brief questionnaire designed to assess family members’ perceptions of empowerment.Citation96 The 34 FES items tap into two dimensions of family empowerment: level of empowerment (family, service system, community/political) and how empowerment is expressed (attitudes, knowledge, behavior). Given the focus of the study, only the family subscale (12 items) that refers to the parents’ management of everyday situations was used. Answers are given on a Likert scale and range from “never” (1) to “very often” (5). Total scores range from 12 to 60, and there is no cutoff.

Parenting Stress Index – Short Form

The PSI-SFCitation37 (Italian version)Citation98 is a self-report questionnaire that aims to identify stressful parent–child relational systems at risk of leading to dysfunctional behavior on the part of the parent or child. The short form (the only one validated in Italy) comprises 36 items scored on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The items are divided into three scales: parental stress, parent–child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult child. The first scale concerns parent’s feelings of being trapped in the parenting role, the second measures the nature of the interaction between the parent and the child, and the third assesses parents’ perceptions of their children.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social SupportCitation97 (Italian version)Citation99 is a brief self-report scale composed of 12 items that measure three areas: perceived social support from family, from friends, and from significant others. Answers can be scored on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). The instrument has no cutoff. The maximum score is 84 and the minimum is 12.

Results

Preliminary analyses

As shown in , our sample of preterm children included 7 children with and 19 without disabilities. Before comparing the quality of family interactions between the preterm group and the group with children born at term, an independent-samples t-test was run between the two preterm subgroups to see whether the presence of disabilities influenced the quality of family interactions. No differences emerged in their total LTP scores (t24=−0.211, P=0.835).

A t-test was also run on the same two subgroups of parents of preterm children to check whether the presence of disabilities influenced their perception of parental empowerment and parenting stress. No differences came to light: PSI total score mother (t21=1.97, P=0.062), PSI total score father (t21=0.712, P=0.484), FES mother (t21=−0.734; P=0.471), FES father (t21=−1.647, P=0.115). As a result of these preliminary analyses, the preterm group was judged to be homogeneous.

Family interactions

Our first aim was to observe the quality of family interactions in a group of families with preterm children compared to a control group of families with infants born at term, exploring the trend of the four possible interactive configurations. Given the homogeneity of the preterm group, a t-test was performed to compare the quality of family interactions between the preterm group and the full-term group, results are given in .

Table 2 Comparison of preterm group with control group (infants born at term)

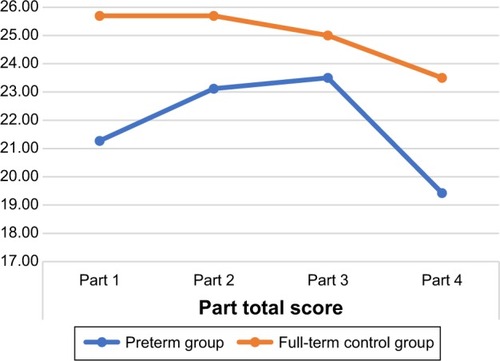

A multivariate analysis of variance was performed between the variables of LTP, showing a significant difference between the preterm group and controls (F9,42=8.395, Wilks’s λ=0.357; P<0.001). Given the significant difference between the two groups, the trend of the four parts characterizing the preterm group was analyzed through a repeated-measures analysis of variance, with the four LTP parts as the within-subject factor. Results showed a significant part effect (F3.75=8.54, P<001) for the preterm group. A Bonferroni post hoc analysis confirmed that the score of the fourth part () was significantly lower than the score of the second (P=0.008) and third (P=0.001) parts.

Influence of parental empowerment, child temperament, parenting stress, and perceived social support on the quality of family interactions

The second aim of our study was to examine the relationship between the quality of family interactions and parental empowerment, child’s temperament, parenting stress, and perceived social support in the group of families with children born preterm. presents a descriptive analysis of all the instruments used for this purpose.

Table 3 Descriptive analysis of QUIT, PSI-SF, FES, MSPSS, and LTP results

Given the homogeneity of the preterm group, even with regard to parental empowerment, child’s temperament, parenting stress, and perceived social support, Pearson’s correlations were run to identify the relationship between the aforementioned constructs and the quality of family interactions. shows the positive correlations. In the preterm group, the relationship between the perception of parental empowerment, the child’s temperament, parenting stress, and perceived social support was also considered. shows the corresponding Pearson’s correlations.

Table 4 Correlations between LTP and PSI-SF, FES, and MSPSS

Table 5 Pearson’s correlations between PSI-SF and QUIT, FES, and MSPSS

Discussion

The general goal of this work was to observe the quality of family interactions in a sample of families with children born preterm and to explore possible differences compared to a normative population. Our results showed a significant difference between these two groups in terms of the quality of family interactions. The control group (families with children born at term) scored significantly higher in the first, second, and fourth parts of the LTP and in the total score. Differences emerged from the sum of the LTP variables – postures and gazes, role implication, parental scaffolding, infant’s involvement, co-construction, validation, and family warmth – confirming a low performance of the preterm group.

Our data were not consistent with the results of GueronSela et al,Citation90 who found no LTP score differences between families with children born preterm and with children born at term when the infant was 6 months old (corrected age). Our hypothesis regarding this incongruity is that it was probably due to the fact that the peculiarities of parental interactions with preterm children start to emerge in the second half of the child’s first year of life, when the child’s environment becomes increasingly complex and demanding.Citation70,Citation74 In other words, our research could be related to this subsequent phase, given the higher mean age of our group.

An important result, however, which is worth emphasizing, concerns an aspect that did not emerge as differing significantly in the comparison between the preterm and full-term groups, ie, the total score for the third part of the procedure (when all three parties should interact actively and mutually), and the sum of the variables “inclusion of partners” and “support and cooperation”. It means that regardless of the aforementioned difficulties, parents of preterm children participate actively and succeed in supporting and cooperating in this triadic interactive configuration so that the interaction is conducted fluidly. The quality of the coparenting alliance does not seem to be negatively influenced by prematurity, suggesting that despite the deficit emerging on a dyadic level regarding both the parent–child relationship and the marital couple, this could be a fundamental resource of these families. This finding also goes to show that even with very young children, there is not a better functioning of the dyadic interaction compared to the triadic one, and/or there is no single active parent, be it mother or father, with whom the child develops an elective functioning. The “best performance” seems to coincide with the situation where both partners are active and cooperative, and probably after a warming period represented by the first two parts.

Taking into account the trend of the four parts of the LTP, it seems that some deficiencies arising at the start of the interactive exchange gradually dissipate, coming to reach the same quality as in the normative families in the third part and subsequently deteriorating again in the fourth and last part, dedicated to the parents’ interactive exchange. It was apparent that parents did not enrich the dialog in the fourth part by considering the stimulus offered by the other partner. They seemed to have a strong tendency to remain focused on the child, as if to underline their greater attention to the child’s activity. In other words, they struggled to leave the child “alone in their presence”.

Our results compare families with preterm children and families with children born at term pointing out difficulties in creating the optimal context for fostering emotional exchanges during interactions through eye contact and posture sharing. There was in fact some evidence of rupture of affect circularity: affect was often shared only on the dyadic level. During dyadic interactions, the parent in the active role seems to use several strategies to engage the child, penalizing eye contact and affect circularity with the third (the other parent), thus influencing family warmth. In this regard, the low score on the variable “role implication” showed that parents had difficulty remaining in the role of the observer, and tended to show signs of wanting to interact with the baby to see their active presence acknowledged.

Lower scores for “parental scaffolding” were awarded mainly because parents gave contradictory signals to the child during the fourth part of the LTP, sometimes taking the child back to their role as an observer, sometimes stimulating them directly. In the other parts of the procedure, parents (and especially mothers) tended to be hypostimulating, a finding not entirely consistent with other reports in literature.Citation60,Citation71,Citation81 This aspect sometimes comes up together with the exclusive use of the verbal channel.Citation71 During the play, the emotions expressed and shared in the preterm group seemed to be mainly neutral. These families had been exposed from the start to their child’s lengthy hospitalization and fragility. They had faced, more or less consciously, the risk of loss, and thus, they could may have found it harder to let themselves go in a free flow of affections and relations.Citation100

We know from the literature that parents of preterm children (and mothers in particular) struggle more in organizing their mental representations of their child and of themselves,Citation101 partly due to the emotional issues raised by prematurityCitation102,Citation103 and partly due to the child’s characteristics,Citation104 and this would prompt a greater “presentification” on the parent’s part. Research highlights that parental scaffolding also seems to be somehow impaired by the difficulty of interpreting the preterm baby’s communicative clues, which are often far from clear.Citation76,Citation77

Parents’ validation of the child’s emotional experience is not stable. They alternate moments of connectivity with child emotions and moments characterized by low sensitivity.Citation84 This aspect could also be seen as a difficulty in interpreting the baby’s uncertain communicative clues, which are not always clear to their parents.Citation76,Citation77 As for the child’s involvement, in some cases children restricted themselves to observing the parents, following the activities with their gaze rather than taking an active part,Citation18 or preferring to play alone. From the triadic and interactive perspective, although our observations stemmed from a new and a different point of view, our study is in line with the literature, in which preterm children are showed to be more passive,Citation60,Citation61 less alert and focused,Citation62,Citation63 and less responsive.Citation64,Citation65

On the whole, families struggled with coconstructing activities, sharing and enriching them, even when the child displayed good levels of ability, communicative expression, and involvement. Our findings about coconstruction ability, are in line with the literature on the characteristics of preterm children, who reportedly establish less eye contact with their caregivers,Citation67–Citation69 display a lesser tendency for some types of behavior, such as gazing, which is commonly considered an important precursor of the first relational exchanges, and thus is an indicator of a greater difficulty in constructing primary intersubjectivity.Citation18,Citation59,Citation69 It could also be said that given the child’s developmental level, the parents’ gaze allows a psychological existence for their child, but also the child’s gaze allows a psychological existence for the parents. From a triadic perspective, right from the first interactions, the child is consequently able to contribute to the characteristics of the family’s interactive dynamics. Overall, our results seem to confirm on the triadic level the difficulties already described in the literature during dyadic interactive exchanges in terms of eye contact with preterm childrenCitation69 and the latter’s expression of mainly neutral affection.Citation18

It is probably particularly difficult for parents and their babies to direct and share attention on a common focus, and this could be due to the parents’ failure to comply with the turn-taking rules, to an interaction rigidly structured by the parent,Citation64 or to a primary deficit in their ability to share through postures and gazes. Parents seemed to find it difficult to connect with the preterm child’s timing, as they tended to anticipate the duration of the child’s activities.

Another focus of this study was to examine in families with preterm children the relationship between family interactions and parental empowerment, the child’s temperament, parenting stress, and perceived social support. In light of the correlations emerged between maternal parenting stress with the sum of the two variables “parental scaffolding” and “respect for the task’s structure and time frame”, couples in which mothers were more stressed seemed to be able to provide appropriate stimulation, probably serving the purpose of offering a frame and a stimulation that secured the child’s engagement and interest, and thereby countering their negative perceptions of the child who had become a source of stress (a low level of attention in particular). The mother is not only less stressed, the more the child proves to be attentive, but she also feels more competent as a parent. This goes to show that it is feasible for these mothers to synchronize/connect with their child, even though it seems to be more stressful and laborious. On the other hand, it may be that struggling to involve their child in the interactive play could make mothers experience this situation as a performance, which would guarantee an appropriate stimulation for the child, but at the same time would also be a source of stress for the mother, giving them a weaker perception of competence.

In agreement with the literature,Citation38 parenting stress seemed to be more severe in parents with preterm children. While the mother’s stress seems to relate to structuring and characterizing aspects of her interactions with the child, the father’s stress is clearly related to specific characteristics of the child. Preterm infants show little outward signs of their communicative skills, and it seems difficult to engage them. A child who has difficulty in regulating themselves also generates further stress on the father, who experiences his interactions with the child as stressful. This makes it more stressful for fathers to relate with the negative emotions of their children.

No correlations have been found between child’s temperament with family interactions, parental empowerment and perceived social support. What emerges from our result is a significant correlation between the variable “attention” and maternal and paternal parenting stress, confirming that parenting stress increases with the decrease of child attention.

Finally, our study confirmed the importance of social support for parents,Citation54,Citation55 which emerged from correlations with parenting stress for both mothers and fathers. For fathers, social support (especially the support perceived as coming from their family) had a stronger influence on the stress they experienced as a function of their parental role and on their parental empowerment. For mothers, it mainly affected their experience of a dysfunctional interaction with their child or their perception of the child as being difficult to manage. The mother’s stress also correlated with the father’s perception of social support, but not vice versa. We hypothesize that a father’s stronger perception of social support could serve as a protective factor for the mother–child dyad too, because its influence on paternal stress would help to guarantee the protective function of the father’s role.

Conclusion

Our research was conducted in a field that has been little studied so far before: observation of the quality of triadic interactions in families with children born preterm. This preliminary work highlights some differences in the interactive exchanges of families with preterm children, both in creating the space appropriate for promoting exchange, involvement, and participation in the child and in aspects relating to emotionality, which does not reveal the positivity to be expected in a playful situation (as happens for families with children born at term). Our most important finding, however, indicates that faced with the difficulties that appear when dyads are expected to interact actively, when all family members should interact mutually, the families with preterm children succeed in contributing to completion of the task, generating pleasant sharing moments. This result, along with the finding regarding parents’ support and cooperation, is an indication of the quality of the coparenting couple and represents the fundamental resource identified in these families. The LTP procedure aims to bring to light a family’s limits, but even more its resources, so that the intervention can then be planned taking the latter into account.Citation105,Citation106 Parents’ capacity of emotional and interactive coordination can be reinforced to create a positive climate where affect can be authentically expressed and shared, and this could certainly be a protective factor, and when treatments are needed, a good basis for building a positive working alliance is finalized to caregiving experience improvement.Citation107–Citation109

The main limits of our research concern the sample size, which was not large enough to allow us the generalization of our results, and the use of self-report questionnaires. Our research group is thus expanding its collaborations with a view to increasing the sample size and consequently becoming able to identify the presence or any differences and peculiarities relating to the degree of prematurity and the child’s birth weight. We are also planning a follow-up to monitor families involved in this study, not only to enrich our knowledge of their subsequent development but also to offer preventive support to the marital and coparenting couples.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationWHO Recommendations on Interventions to Improve Preterm Birth OutcomesGeneva, SwitzerlandWHO2015

- Ministero della SaluteNuovo rapporto CeDAP, analisi dell’evento nascita in Italia2012 Available from: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/news/p3_2_1_1_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=notizie&p=dalministero&id=459Accessed May 30, 2017

- SpittleAJWalshJOlsenJENeurobehaviour and neurological development in the first month after birth for infants born between 32–42 weeks’ gestationEarly Hum Dev20169671426964011

- MentoGBisiacchiPSSviluppo neuro-cognitivo in nati pretermine:la prospettiva delle Neuroscienze cognitive dello sviluppoPsicol Clin Sviluppo2013172744

- JohnsonSMarlowNPreterm birth and childhood psychiatric disordersPediatr Res20116911R18R

- MontagnaANosartiCSocio-emotional development following very preterm birth: pathways to psychopathologyFront Psychol201678026903895

- BhuttaATClevesMACaseyPHCradockMMAnandKJCognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born pretermJAMA200228872873712169077

- SaigalSDoyleLWAn overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthoodLancet200837126126918207020

- HoffBHansenBMMunckHMortensenELBehavioral and social development of children born extremely premature: 5-year follow-upScand J Psychol20044528529215281917

- WolkeDPsychological development of prematurely born childrenArch Dis Child1998785675709713018

- ColettiMFCaravaleBGaspariniCFrancoFCampiFDottaAOne-year neurodevelopmental outcome of very and late preterm infants: risk factors and correlation with maternal stressInfant Behav Dev201539112025779697

- GrunauRWhitfieldMFPetrie-ThomasJNeonatal pain, parenting stress and interaction, in relation to cognitive and motor development at 8 and 18 months in preterm infantsPain200914313814619307058

- BöhmBSmedlerACForssbergHImpulse control, working memory and other executive functions in preterm children when starting schoolActa Paediatr2004931363137115499959

- MarlowNHennessyEMBracewellMAWolkeDMotor and executive function at 6 years of age after extremely preterm birthPediatrics200712079380417908767

- NosartiCGiouroukouEMicaliNRifkinLMorrisRGMurrayRMImpaired executive functioning in young adults born very pretermJ Int Neuropsychol Soc20071357158117521479

- MulderHPitchfordNJHaggerMSDevelopment of executive function and attention in preterm children: a systematic reviewDev Neuropsychol20093439342120183707

- SansaviniAPentimontiJJusticeLLanguage, motor and cognitive development of extremely preterm children: modeling individual growth trajectories over the first three years of lifeJ Commun Disord201449556824630591

- SansaviniAGuariniASaviniSLongitudinal trajectories of gestural and linguistic abilities in very preterm infants in the second year of lifeNeuropsychologia2011493677368821958647

- Stene-LarsenKBrandlistuenRELangAMLandoltMALatalBVollrathMECommunication impairments in early term and late preterm children: a prospective cohort study following children to age 36 monthsJ Pediatr20141651123112825258153

- BarreNMorganADoyleLWAndersonPJLanguage abilities in children who were very preterm and/or very low birth weight: a meta-analysisJ Pediatr201115876677421146182

- de KievietJFPiekJPAarnoudse-MoensCSOosterlaanJMotor development in very preterm and very low-birth-weight children from birth to adolescence: a meta-analysisJAMA20093022235224219934425

- ArpiEFerrariFPreterm birth and behavior problems in infants and preschool-age children: a review of the recent literatureDev Med Child Neurol20135578879623521214

- PerriconeGMoralesMRThe temperament of preterm infant in pre-school ageItal J Pediatr201137421219632

- GhorbaniMDolatianMShamsJAlavi-MajdHTavakolianSFactors associated with posttraumatic stress disorder and its coping styles in parents of preterm and full-term infantsGlob J Health Sci20146657324762347

- Holditch-DavisDSchwartzTBlackBScherMCorrelates of mother-premature infant interactionsRes Nurs Health20073033334617514707

- DavisLEdwardsHMohayHWollinJThe impact of very premature birth on the psychological health of mothersEarly Hum Dev200373617012932894

- WuCHungCChangYPredictors of health status in mothers of premature infants with implications for clinical practice and future researchWorldviews Evid Based Nurs20151221722726220369

- ZanardoVFreatoFZacchelloFMaternal anxiety upon NICU discharge of high-risk infantsJ Reprod Infant Psycol2003216975

- VoegtlineKMStifterCALate-preterm birth, maternal symptomatology, and infant negativityInfant Behav Dev20103354555420732715

- ShawRJLiloEAStorfer-IsserAScreening for symptoms of postpartum traumatic stress in a sample of mothers with preterm infantsIssues Ment Health Nurs20143519820624597585

- MilesMSHolditch-DavisDSchwartzTAScherMDDepressive symptoms in mothers of prematurely born infantsJ Dev Behav Pediatr200728364417353730

- SilversteinMFeinbergEYoungRSauderSMaternal depression, perceptions of children’s social aptitude and reported activity restriction among former very low birth weight infantsArch Dis Child20109552152520522473

- VigodSNVillegasLDennisCLRossLEPrevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: a systematic reviewBJOG201011754055020121831

- HelleNBarkmannCEhrhardtSvon der WenseANestoriucYBindtCPostpartum anxiety and adjustment disorders in parents of infants with very low birth weight: cross-sectional results from a controlled multicentre cohort studyJ Affect Disord201619412813426820762

- PierrehumbertBNicoleAMuller-NixCForcada-GuexMAnsermetFParental post-traumatic reactions after premature birth: implications for sleeping and eating problems in the infantArch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed200388F400F40412937044

- ShawRJBernardRSDebloisTIkutaLMGinzburgKKoopmanCThe relationship between acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder in the neonatal intensive care unitPsychosomatics20095013113719377021

- AbidinRRParenting Stress Index – Short FormCharlottesville, VAPediatric Psychology Press1990

- GrayPHEdwardsDMO’CallaghanMJCuskellyMGibbonsKParenting stress in mothers of very preterm infants: influence of development, temperament and maternal depressionEarly Hum Dev20138962562923669559

- OlafsenKSKaaresenPIHandegårdBHUlvundSEDahlLBRønningJAMaternal ratings of infant regulatory competence from 6 to 12 months: influence of perceived stress, birth-weight, and intervention – a randomized controlled trialInfant Behav Dev20083140842118282607

- BeckCTThe effects of postpartum depression on maternal-infant interaction: a meta-analysisNurs Res1995442983057567486

- FieldTPostpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: a reviewInfant Behav Dev2010331619962196

- LovejoyMCGraczykPAO’HareENeumanGMaternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic reviewClin Psychol Rev20002056159210860167

- SteinAPearsonRMGoodmanSHEffects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and childLancet20143841800181925455250

- BrowneJVTalmiAFamily-based intervention to enhance infant-parent relationships in the neonatal intensive care unitJ Pediatr Psychol20053066767716260436

- SameroffAJFieseBHTransactional regulation: the development ecology of early interventionShonkoffJPMeiselsSJHandbook of Early Childhood InterventionCambridgeCambridge University Press2000135159

- CussonRMFactors influencing language development in preterm infantsJ Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs200332402409

- EvansTWhittinghamKBoydRWhat helps the mother of a preterm infant become securely attached, responsive and well-adjusted?Infant Behav Dev20123511122078206

- McManusBMPoehlmannJParent-child interaction, maternal depressive symptoms and preterm infant cognitive functionInfant Behav Dev20123548949822721747

- SantosHYangQDochertySLWhite-TrautRHolditch-DavisDRelationship of maternal psychological distress classes to later mother-infant interaction, home environment, and infant development in preterm infantsRes Nurs Health20163917518627059608

- MontirossoRArrigoniFCasiniEGreater brain response to emotional expressions of their own children in mothers of preterm infants: an fMRI studyJ Perinatol20173771672228151495

- Holditch-DavisDCoxMFMilesMSBelyeaMMother-infant interactions of medically fragile infants and non-chronically ill premature infantsRes Nurs Health20032630031112884418

- ChengERKotelchuckMGersteinEDTaverasEMPoehlmann-TynanJPostnatal depressive symptoms among mothers and fathers of infants born preterm: prevalence and impacts on children’s early cognitive functionJ Dev Behav Pediatr201637334226536007

- WeissSJChenJLFactors influencing maternal mental health and family functioning during the low birthweight infant’s first year of lifeJ Pediatr Nurs20021711412512029605

- GhorbaniMDolatianMShamsJAlavi-MajdHAnxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and social supports among parents of premature and full-term infantsIran Red Crescent Med J201416e1346124829766

- SingerLTDavillierMBrueningPHawkinsSYamashitaTSocial support, psychological distress, and parenting strains in mothers of very low birthweight infantsFam Relat19964534335025431508

- DeckerKAMillerWRBuelowJMParent perceptions of family social supports in families with children with epilepsyJ Neurosci Nurs20164833634127824801

- WakimizuRYamaguchiKFujiokaHFamily empowerment and quality of life of parents raising children with developmental disabilities in 78 Japanese familiesInt J Nurs Sci201743845

- BozzetteMA review of research on premature infant-mother interactionNewborn Infant Nurs Rev200774955

- KorjaRLatvaRLehtonenLThe effects of preterm birth on mother-infant interaction and attachment during the infant’s first two yearsActa Obstet Gynecol Scand20129116417322007730

- Muller-NixCForcada-GuexMPierrehumbertBJauninLBorghiniAAnsermetFPrematurity, maternal stress and mother-child interactionsEarly Hum Dev20047914515815324994

- HughesMBShultsJMcgrathJMedoff-CooperBTemperament characteristics of premature infants in the first year of lifeJ Dev Behav Pediatr20022343043512476073

- HallRAHoffenkampHNTootenABraekenJVingerhoetsAJvan BakelHJThe quality of parent-infant interaction in the first 2 years after full-term and preterm birthParent Sci Pract201515247268

- MindeKPerrottaMMartonPMaternal caretaking and play with full-term and premature infantsJ Child Psychol Psychiatr198526231244

- ReisslandNStephensonTTurn-taking in early vocal interaction: a comparison of premature and term infants’ vocal interaction with their mothersChild Care Health Dev19992544745610547707

- SingerLTFultonSDavillierMKSalvatorABaleyJEEffects of infant risk status and maternal psychological distress on maternal-infant interactions during the first year of lifeJ Dev Behav Pediatr20032423324112915795

- SalerniNSuttoraCD’OdoricoLA comparison of characteristics of early communication exchanges in mother-preterm and mother-full-term infant dyadsFirst Lang200727329346

- MalatestaCZGrigoryevPLambCAlbinMCulverCEmotion socialization and expressive development in preterm and full-term infantsChild Dev1986573163303956316

- HarelHGordonIGevaRFeldmanRGaze behaviors of preterm and full-term infants in nonsocial and social contexts of increasing dynamics: visual recognition, attention regulation, and gaze synchronyInfancy2011166990

- TenutaFCostabileAMarconeRCorchiaCLombardiOLa comunicazione precoce madre-bambino: un confronto tra diadi con bambino nato a termine e bambino nato preterminePsicol Clin Sviluppo200812357378

- CrnicKARagozinASGreenbergMTRobinsonMNBashamRBSocial interaction and developmental competence of preterm and full-term infants during the first year of lifeChild Dev198354119912106354627

- SchmückerGBrischKHKöhntopBThe influence of prematurity, maternal anxiety, and infants’ neurobiological risk on mother-infant interactionsInfant Ment Health J20052642344128682494

- MontirossoRBorgattiRTrojanSZaniniRTronickEA comparison of dyadic interactions and coping with still-face in healthy pre-term and full-term infantsBr J Dev Psychol20102834736820481392

- De SchuymerLDe GrooteIStrianoTStahlDRoeyersHDyadic and triadic skills in preterm and full term infants: a longitudinal study in the first yearInfant Behav Dev20113417918821185604

- KorjaRMaunuJKirjavainenJMother-infant interaction is influenced by the amount of holding in preterm infantsEarly Hum Dev20088425726717707118

- HsuHCJengSFTwo-month-olds’ attention and affective response to maternal still face: a comparison between term and preterm infants in TaiwanInfant Behav Dev20083119420618035422

- FeldmanREidelmanAIMaternal postpartum behavior and the emergence of infant-mother and infant-father synchrony in preterm and full-term infants: the role of neonatal vagal toneDev Psychobiol20074929030217380505

- OlafsenKSRønningJAHandegårdBHUlvundSEDahlLBKaaresenPIRegulatory competence and social communication in term and preterm infants at 12 months corrected age: results from a randomized controlled trialInfant Behav Dev20123514014921908049

- LandrySHPreterm infants’ responses in early joint attention interactionsInfant Behav Dev19869114

- DavisDWBurnsBSnyderEDossettDWilkersonSAParent-child interaction and attention regulation in children born prematurelyJ Spec Pediatr Nurs20049859415553550

- ReaLMamonePSantirocchiGBraibantiPEffetti della marsupioterapia sulle interazioni precoci madre-bambino pretermineEta Evol199862311

- AgostiniFNeriEDellabartolaSBiasiniAMontiFEarly interactive behaviours in preterm infants and their mothers: influences of maternal depressive symptomatology and neonatal birth weightInfant Behav Dev201437869324463339

- Schermann-EizirikLHagekullBBohlinGPerssonKSedinGInteraction between mothers and infants born at risk during the first six months of corrected ageActa Paediatr1997868648729307169

- GernerEMEmotional interaction in a group of preterm infants at 3 and 6 months of corrected ageInfant Child Dev19998117128

- HarrisonMJMagill-EvansJMother and father interactions over the first year with term and preterm infantsRes Nurs Health1996194514598948399

- FeldmanRMaternal versus child risk and the development of parent-child and family relationships in five high-risk populationsDev Psychopathol20071929331217459172

- KmitaGKiepuraEMajosAPaternal involvement and attention sharing in interactions of premature and full-term infants with fathers: a brief reportPsychol Lang Commun201418190203

- BlanchardCde CosterLQuel intérêt pour la recherche et la clinique de mieux comprendre la trajectoire développementale familiale suite à la naissance prématurée d’un enfant? Projet de rechercheTher Fam201334317332

- TreyvaudKDoyleLWLeeKJFamily functioning, burden and parenting stress 2 years after very preterm birthEarly Hum Dev20118742743121497029

- Fivaz-DepeursingeECorboz-WarneryAIl Triangolo Primario: Le Prime Interazioni Triadiche tra Padre, Madre, e BambinoMilanRaffaello Cortina Editore1999

- Gueron-SelaNAtzaba-PoriaNMeiriGMarksKThe caregiving environment and developmental outcomes of preterm infants: diathesis stress or differential susceptibility effects?Child Dev20158610141030

- SimonelliAParolinMSacchiCde PaloFVienoAThe role of father involvement and marital satisfaction in the development of family interactive abilities: a multilevel approachFront Psychol20167172527872601

- LandrySHSmithKESwankPRAsselMAVelletSDoes early responsive parenting have a special importance for children’s development or is consistency across early childhood necessary?Dev Psychol20013738740311370914

- LandrySHSmithKESwankPRResponsive parenting: establishing early foundations for social, communication, and independent problem solving skillsDev Psychol20064262764216802896

- SimonelliABighinMde PaloFCoparenting interactions observed by the prenatal Lausanne trilogue play: an Italian replication studyInfant Ment Health J20123360961928520113

- AxiaGQUIT: Questionari Italiani del TemperamentoTrento, ItalyErickson2002

- KorenPEDe ChilloNFriesenBJMeasuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: a brief questionnaireRehabil Psychol199237305321

- ZimetGDDahlemNWZimetSGFarleyGKThe multidimensional scale of perceived social supportJ Pers Assess1988523041

- GuarinoADi BlasioPD’AlessioMCamisascaESerantoniGParenting Stress Index: Forma BreveFlorenceGiunti Organizzazioni Speciali2008

- PrezzaMPrincipatoMCLa rete sociale e il sostegno socialePrezzaMSantinelloMConoscere la Comunità: Analisi degli Ambienti di Vita QuotidianaBolognaIl Mulino2002193234

- ArockiasamyVHolstiLAlbersheimSFathers’ experiences in the neonatal intensive care unit: a search for controlPediatrics2008121e215e22218182470

- VizzielloGMCalvoVLa perdita della speranza: effetti della nascita prematura sulla rappresentazione genitoriale e sullo sviluppo dell’attaccamentoSaggi199711535

- VizzielloGMCalvoVCadrobbiMPrematurità e psicopatologia in età prescolare: fattori di rischio neonatali e affettivo-relazionaliPsicol Clin Sviluppo20004441463

- SperanzaAMRogoraCTrentiniCBacigalupiMBaquèBLenaFInteraction between mothers and premature infants during the first two years of life: parental stress and infant emotional-adaptive functioningInfant Ment Health J201031Suppl 1P321

- VizzielloGMQuando nasceun bambino prematuroRighettiPLGravidanza e Contesti Psicopatologici: Dalla Teoria agli Strumenti di InterventoMilanFranco Angeli Editore2010164186

- GattaMMisciosciaMSimonelliAContribution of analyses on triadic relationships to diagnostics and treatment planning in developmental psychopathologyPsychol Rep201712029030428558624

- GattaMMisciosciaMBriandaMESimonelliAAssessment and intervention in mental health services for children and adolescents using the Lausanne trilogue playClin Neuropsychiatry201714216225

- GattaMRamaglioniELaiJPsychological and behavioral disease during developmental age: the importance of the alliance with parentsNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2009554154619898668

- GattaMDal ZottoLNequinioGParents of adolescents with mental disorders: improving their caregiving experienceJ Child Fam Stud201120478490

- GattaMBalottinLMannariniSBirocchiVDel ColLBattistellaPAParental stress and psychopathological traits in children and adolescents: a controlled studyRiv Psichiatr20165125125927996985