Abstract

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a neuropsychiatric disorder with typical onset in childhood and characterized by chronic occurrence of motor and vocal tics. The disorder can lead to serious impairments of both quality of life and psychosocial functioning, particularly for those individuals displaying complex tics. In such patients, drug treatment is recommended. The pathophysiology of TS is thought to involve a dysfunction of basal ganglia-related circuits and hyperactive dopaminergic innervations. Congruently, dopamine receptor antagonism of neuroleptics appears to be the most efficacious approach for pharmacological intervention. To assess the efficacy of the different neuroleptics available, a systematic, keyword-related search in PubMed (National Library of Medicine, Washington, DC) was undertaken. Much information on the use of antipsychotics in the treatment of TS is based on older data. Our objective was to give an update and therefore we focused on papers published in the last decade (between 2001 and 2011). Accordingly, the present review aims to summarize the current and evidence-based knowledge on the risk-benefit ratio of both first and second generation neuroleptics in TS.

Introduction

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a serious, often intractable neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by enduring though waxing and waning phonic (vocal) and motor tics. Contrary to the earlier perception of TS as a psychogenic disorder, its neurobiological basis has been proven, although the exact mechanisms are not yet fully understood.Citation1 Once tics have emerged, usually by the age of about 6–8 years, they reach a maximum at around 12 years. About 40% of all TS patients show a gradual to complete spontaneous remission of symptoms in early adulthood.Citation2 Drug treatment is recommended for children who suffer from severe tics and adults with persistent and significantly impairing symptoms as a result of TS.

The pathophysiology is thought to involve a dysfunction of basal ganglia-related circuits and hyperactive dopaminergic innervations.Citation3 Studies supporting the strong hypothesis of an imbalance in the dopaminergic system have shown an increased number of striatalCitation4 and corticalCitation5 dopamine receptors, as well as altered dopamine binding properties in the basal ganglia.Citation6,Citation7 Therefore, the main action of drugs used in the treatment of tics is the modulation of the dopaminergic metabolism. In this context, research is still focusing on the D2 receptor systemCitation5 and congruently D2 receptor antagonism appears to be the most efficacious approach for pharmacological intervention.Citation8 For 40 years, the beneficial effects of D2 receptor blocking in the treatment of tics have been reported, with an average success rate of 70%.Citation9 In general, typical or first generation antipsychotics are thought to have a very high dopamine blocking potency. Hence, they are thought to be very effective in ameliorating tics.Citation10 However, these agents might be associated with severe adverse events, because a strong D2 receptor antagonism is connected with high rates of extrapyramidal symptoms (parkinsonism, akathisia, tardive dyskinesia) or even hyperprolactinemia. Furthermore, they also alter cholinergic, serotonergic, histaminergic, and alpha-adrenergic transmission and thereby might lead to weight gain, drowsiness, and excessive sedation. Atypical or second generation neuroleptics usually have a greater affinity for 5-HT2 receptors than for D2 receptors which is associated with fewer extrapyramidal side effectsCitation11 than seen under typical neuroleptics.

As a result of frequent adverse events caused by antipsychotics, attempts have been made to use other medications for the treatment of TS such as noradrenergic agents (clonidine, guanfacine, atomoxetine) or tetrabenazine, nicotine, tetrahydrocannabinol, talipexole, clonazepam, baclofen, levetiracetam, topiramate, lithium, or naloxone (as shown in the paper by Roessner et alCitation9). As well as pharmacological treatment, psychotherapy or rather, habit reversal trainingCitation12 can be helpful if patients are willing to engage in it. Finally, deep brain stimulation should be considered for therapy-resistant patients because it can successfully expand the limits of medication-based treatment options.Citation13

Methods

Given the big impact of neuroleptics in the treatment of TS, the intention of this review is to give an update on the evidence-based, risk-benefit ratio of the different available antipsychotics.

Therefore, a systematic literature search was carried out in PubMed including articles published from 2001 to May 2011. The search terms were “antipsychotics and Tourette syndrome” plus “neuroleptics and Tourette syndrome”. By using a combination of these search terms we identified 175 articles published in German or English. In the first step, all titles and abstracts were screened carefully for aspects relevant to our main topic. Our second step was an analysis of the full texts to identify valuable information. In this process, we checked whether the information presented was collected in clinical studies with high methodological standards or from case reports or incidental findings. We used 43 articles in the present paper, found by using the research criteria described above; 132 articles were excluded. In addition, references for the identified articles were screened for further relevant literature not listed in PubMed or beyond our search period. In this way, another 89 articles were found and considered in the present review.

Results

Typical antipsychotics

Haloperidol

The butyrophenone haloperidol was the first drug used in treatment for TS and remains the most widely used agent for this indication worldwide. The first report on its empirical use in TS concerned an adult who had already undergone a frontal lobectomy.Citation14 Haloperidol was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of adult TS patients in 1969 and for children in 1978.Citation15 Due to its strong blocking effect on D2 receptors, tic reductions of 78%–91% at a maximum dosage of 10 mg have been estimated.Citation16,Citation17 The most commonly observed adverse events are extrapyramidal reactions (parkinsonism, tardive dyskinesia), neuroleptic malignant syndrome, drowsiness, restlessness, and sexual dysfunction. In our search period, we were unable to find any valuable studies. The approval of haloperidol is based mainly on its effectiveness known from older comparison studies with pimozide, fluphenazine, and placebo. An early randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled study showed that haloperidol and pimozide decrease tic frequency significantly. Citation18 Some studies stated that haloperidol is superior to both placebo and pimozide.Citation16 However, in another study including 22 patients the effect of haloperidol was described as inferior to pimozide and even to placebo.Citation19 Yet another study suggested that treatment with haloperidol is more often discontinued than with pimozide, even though both drugs produced comparable relief of symptoms.Citation20 Additionally, haloperidol produced significantly more acute dyskinesia/dystonia than pimozide. Some studies suggested that other, similar, agents such as pimozideCitation19 and fluphenazineCitation21 may be as efficacious as haloperidol, but with fewer side effects and a slightly better patient tolerance.

Conclusion

Although the evidence is not consistent, based on clinical experience, haloperidol may be an effective agent for the treatment of TS. Older studies (data collection before 1997) suggested that it is less tolerable and is more often associated with adverse events than other typical neuroleptics. For this reason, haloperidol should be used mainly as a spare medication in severely diseased patients.Citation22

Pimozide

Pimozide is a D2 receptor antagonist which in addition blocks calcium channelsCitation11 and to a lesser extent D1 receptors. It exhibits less noradrenaline (alpha1) antagonism than haloperidol, and less sedation.Citation22 Pimozide can be associated with severe arrhythmia and prolongation of the QTc interval. Citation23 The most recent article about the efficacy of pimozide is a comprehensive Cochrane review from 2009 reporting on six randomized controlled trials with a total of 162 participants.Citation24 The comparison between pimozide, haloperidol, and risperidone revealed inconsistent results. Pimozide, however, was shown to be considerably more effective than placebo. Inconsistency of results is brought about by three double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of pimozide versus haloperidol: one revealed equal efficacy, another found haloperidol slightly more effective than pimozide, while yet another showed pimozide to be superior to haloperidol. Pimozide is further described as having fewer side effects (including sedation and extrapyramidal symptoms) than haloperidol. In two trials comparing pimozide with risperidone, no significant differences between the two drugs in terms of efficacy or side-effect profile could be identified.Citation25,Citation26

Conclusion

In our opinion, pimozide is indicated for the suppression of tics in patients who have failed to respond satisfactorily to standard treatment with the frequently recommended agent risperidone. As a rather older compound with a considerable cardiac risk profile, we support the appraisal for pimozide as a reserve treatment especially because no substantial new data have been acquired in recent years. Singer favored pimozide as second choice medication in his helpful suggestions.Citation11

Fluphenazine

Fluphenazine acts as both a D1 and D2 receptor antagonist.Citation11 It has been used particularly in the US for many years to treat TS, though it has simply been studied systematically.Citation9 Our search period included only a small amount of current data. A naturalistic follow-up study from 2004 including 41 patients indicated that treatment with fluphenazine for at least one year was safe and effective.Citation27 A retrospective review from 2009 also showed fluphenazine to be an effective and well-tolerated therapy.Citation28 The main data were collected in a few older studies including placebo-controlled, double-blind trials between 1982 and 1985 which revealed that fluphenazine is effective in controlling tics, while having fewer side effects than haloperidol (small, open-label studies).Citation29–Citation31

Conclusion

Although fluphenazine has been shown to be an effective and well-tolerated therapy for TS, we would not unconditionally recommend its use due to the lack of recent studies comparing this drug to newer medications such as atypical antipsychotics. Yet, it is also favored by Singer as second choice medication.Citation11

Atypical antipsychotics

Benzamide

The benzamides (tiapride, sulpiride, and amisulpride) are a class of amides of benzoic acid and further selective D2 receptor antagonists.Citation32 Substituted benzamides are effective in the treatment of tics and it seems that the occurrence of extrapyramidal side effects is unusual.Citation22

In Germany, benzamides (especially tiapride) are used as first-line medication in the treatment of TS, particularly in children and young adults. The lack of studies investigating the efficacy of these agents might be explained by the fact that tiapride and sulpiride are not available in the US.Citation8

Tiapride

Tiapride has a selective antagonistic effect on D2 receptors, especially in the ventral striatum and in parts of the limbic system.Citation9 Although this drug is in general well-suited for the treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorders which are associated with functional dopamine hyperactivityCitation33 and is even considered as first choice in European guidelines,Citation9 no clinical studies focusing on the treatment with tiapride in humans were found in our search period. There is only one case report from 2004 about a patient with severe side effects such as massive weight gain, hyperprolactinemia, amenorrhea, and sedation under therapy with tiapride.Citation34 Nevertheless, there are two animal studies investigating the effects of tiapride, suggesting that this drug does not lead to long-lasting alterations of dopamine concentration or other severe short- and long-term adverse reactions in young rats.Citation35,Citation36 Thus evidence for its clinical efficacy in humans is mostly based on older studies. Since the 1970s, some case reports and placebo-controlled studies have reported the success of TS treatment with tiapride.Citation37–Citation39 Only one randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled crossover study from 1988 investigated the effects of tiapride in 17 children. The results yielded beneficial therapeutic effects on tic symptomatology, while no adverse effects on children’s cognitive functioning were reported.Citation40 Drowsiness, modest transient hyperprolactinemia, and moderate weight gain have been observed as side effects.

Conclusion

Despite the lack of actual studies, the treatment of TS with tiapride should still be considered, especially because of its moderate side effects, which have been confirmed by translational studies and clinical experience. Citation9 Nevertheless, further well-designed studies and head-to-head comparisons would be desirable.

Sulpiride

Sulpiride is a highly selective D2 and D3 receptor antagonist with antipsychotic and antidepressant mechanisms as well as anxiolytic effects.Citation41 It was first used for the treatment of TS in 1970.Citation42 Usually, few adverse events are reported with its use (eg, sedation and sustained drowsiness in up to 25%).Citation32 Less frequent side effects are restlessness, as well as sleep problemsCitation43 and depressive symptoms, which occur despite the antidepressant and mood-stabilizing effects of sulpiride.Citation44 Increased appetite and as a consequence weight gain may occur, which is probably attributable to the stimulating effects of prolactin secretion causing galactorrhea and amenorrhea.Citation45,Citation46 Due to its rare extrapyramidal and vegetative side effects, sulpiride is probably one of the most prescribed medications in the treatment of tics in TS in Europe.Citation18

One recent prospective, open-label, study investigated the effect of low-dose sulpiride treatment of children and adolescents with TS or chronic tic disorder. The 189 treated patients demonstrated a significant reduction in tic symptomatology after a period of 6 weeks. The most common adverse events were sedation (16% of the patients), which often disappeared 1–2 weeks after treatment onset.Citation47 These promising results are supported by older studies. Robertson and colleagues for example documented in 1990 a positive effect of treatment with sulpiride in 59% of patients. Furthermore, besides tic reduction, a significant decrease in other phenomena such as echophenomena, aggression, subjective tension, and obsessive compulsive traits was found.Citation44 In a placebo-controlled crossover study the treatment effects of fluvoxamine and sulpiride in patients suffering from TS and obsessive compulsive disorders were compared. Sulpiride monotherapy was shown to reduce tics significantly.Citation48

Conclusion

Given the previously described data, the treatment of mild-to-moderate TS or chronic tic disorder with sulpiride can be recommended.Citation9,Citation44 Even in low doses, sulpiride seems to be effective and is usually associated with few adverse events.

Amisulpride

Amisulpride is a highly selective benzamide with 10× higher affinity to D2 and D3 receptors than sulpiride and with little activity at serotonergic, histaminergic, or muscarinic receptors. Citation32 While the agonistic effects on presynaptic D2/D3 receptors prevail at lower doses (increased dopamine transmission), at higher doses, amisulpride acts preferentially on postsynaptic D2/D3 receptors, reducing dopaminergic transmission.Citation32

Randomized controlled studies on the treatment of TS with amisulpride are lacking. As far as we know, only three case reports have been published on the treatment of TS with amisulpride, of which one was published in French.Citation49 The second case report describes the effective treatment of TS with moderate doses of amisulpride (maximum 400 mg/day). One adverse event concerning amenorrhea was reported by a patient.Citation50 Another case report on a patient with atypical TS as a tardive dyskinesia, indicated a change of medication from olanzapine to amisulpride.Citation51

Conclusion

Because of the lack of randomized controlled studies, amisulpride cannot be recommended as first-line medication for the treatment of TS. Amisulpride could be seen as a second-choice medication given several expert opinions.Citation32 Further studies are necessary to obtain valid results on its effectiveness.

Clozapine

Clozapine was first introduced in Europe in 1971, and was approved by the FDA to treat refractory schizophrenia in 1989.Citation52 It acts as a 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT3 antagonist and, to a lesser extent, as a D1 antagonist.Citation9 It has only a weak D2 blocking effect and may therefore be less effective in treating tics than other antipsychotics. A few older studies reported successful reductions in tics during monotherapy (as shown by Jaffe et alCitation53 in the context of tardive TS) or in combination with propanolol or tetrabenazine.Citation54 However, clozapine has not been found helpful in the treatment of TS as stated by several case reports which also documented serious adverse events (eg, agranulocytosis) associated with this agent.Citation55 Furthermore, the occurrence of stuttering, facial tics, myoclonic seizures,Citation56 and even the exacerbation of tics seems to be related to the administration of clozapine.Citation57

Conclusion

Due to the lack of efficacy and its potentially severe side effects, we would not recommend clozapine for the treatment of TS symptoms.

Risperidone

Risperidone acts as a 5-HT2 receptor antagonist at low doses and as a D2 antagonist at higher doses.Citation58 It, too, has moderate-to- high affinity for α1-adrenergic, D3, D4, and H1-histamine receptors.Citation11 Risperidone can prolong the QTc interval, and weight gain can be an emerging problem.Citation58–Citation61 Our search period includes many well-executed studies. Bruggeman and colleagues suggest that risperidone may improve tic symptoms in 30%–62% of patientsCitation25 although some studies have reported even greater success rates.Citation62 The efficacy of risperidone has been confirmed by two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.Citation63,Citation64 Furthermore, risperidone was found to be equally effective or possibly slightly more effective than pimozide in two randomized, double-blind, crossover studies.Citation25,Citation26 Compared with haloperidol, risperidone showed slightly better tic reduction (28% vs 21%) but the difference in efficacy between the two drugs was not significant.Citation65 In a randomized, double-blind study, risperidone and clonidine appeared equally effective in the treatment of tics.Citation66 Additionally, many older studies reported a positive responseCitation67–Citation70 with a similar efficacy to haloperidol. A high discontinuation rate seems to be one major drawback in the use of risperidone. It is suggested that only 20%–30% of patients can tolerate the use of this medication in the long term due to the associated side effects.Citation71 Risperidone was also effective in treating obsessive–compulsive symptoms.Citation25,Citation66,Citation72 Moreover, risperidone could also be useful in ameliorating aggressive behaviour.Citation73,Citation74

Conclusion

The effectiveness of risperidone has been proven in several studies with high methodical demands. It seems that this drug is as effective as haloperidol in treating tics and may be also effective in treating comorbidities like obsessive–compulsive and aggressive symptoms. Therefore, we recommend risperidone as standard therapy. An unfavorable aspect of risperidone is the high discontinuation rate which may be due to common adverse events like fatigue, somnolence, and weight gain.Citation22

Olanzapine

Olanzapine is an atypical neuroleptic with moderate-to-high affinity for D2, D4, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and α-1 adrenergic receptors, as well as D1 receptors.Citation75 Compared with other antipsychotics, olanzapine has greater activity at serotonin 5-HT2 receptors than at D2 receptors,Citation76 which may explain the few extrapyramidal effects. A lower incidence of hyperprolactinemia than with typical antipsychotic agents or risperidone could be explained by the presumption that this drug does not appear to block dopamine within the tuberoinfundibular tract. The most widely reported adverse reactions were drowsiness/sedation and increased appetite, frequently followed by weight gain.Citation77,Citation78 Because of metabolic adverse reactions, caution is recommended in case of hyperglycemia and diabetes. Recently published open-label trials have shown improvement in tic scores.Citation76,Citation77 In 60 children treated for 4 weeks with either olanzapine or haloperidol, efficacy in terms of tic severity reduction and global clinical impression was found to be 74% for both groups, though olanzapine was associated with fewer side effects.Citation81 Other studies indicated that olanzapine leads to significant reductions in tic severity and even in aggression. The only identified drawback was weight gain.Citation75 In an older, double-blind, crossover study, olanzapine seemed to be better at reducing tics in four patients with severe tics compared with low-dose pimozide.Citation80 In addition, several older case reportsCitation81–Citation84 and open-label studiesCitation85,Citation86 have suggested efficacy of olanzapine in the treatment of TS in adolescents and adults.

Conclusion

The major drawback of olanzapine is the valid concern about adverse metabolic effects and weight gain as known from the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Apart from this, the early use of olanzapine to treat TS can be recommended based on studies which have shown olanzapine to be as effective as haloperidol or pimozide. Additionally, this drug can reduce symptoms of ADHD and aggression.Citation22

Quetiapine

Quetiapine antagonizes 5-HT1a, 5-HT2, D2, histamine H1, and α1 and α2 adrenergic receptors.Citation11 Up to now, its efficacy for tic suppression is based solely on case reports which include, for example, the effective treatment of two children with TS.Citation87 In an open-label trial with twelve children, quetiapine reduced tics significantly.Citation88 In the beginning, the main adverse event was sedation. During the 8 weeks under investigation, patients did not experience extrapyramidal adverse reactions and no statistically significant weight gain. Quetiapine reduced tic severity scores by over 60% after week 4 in a retrospective review of 12 patients of ages 8–18 years in which, contrary to the study mentioned before, the only noteworthy adverse reaction was increased weight.Citation89

Conclusion

The few available studies which mainly concentrate on patients under 18 years suggest that quetiapine could be effective in the treatment of TS and is associated with a tolerable side-effect profile, although weight gain and fatigue are fairly common. Due to the lack of methodologically well-executed studies, no further statement can be given.

Ziprasidone

Ziprasidone pharmacological actions work by D2 and 5-HT antagonism and blocking other neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, serotonin, and adrenaline. It also has a moderate affinity for H1 receptors. The near absence of weight gain makes it attractive for the treatment of TS in obese patients.Citation90 Generally, ziprasidone has a higher risk for prolongation of the QT-interval than other compounds such as risperidone, olanzapine, or haloperidol.Citation11 The most frequently reported adverse event is a mild transient somnolence.Citation91,Citation92 An open-label study including 24 children and adolescents with tic disorders indicated that a single dose of ziprasidone was well tolerated without clinically significant effects on electrocardiogram.Citation93 Efficacy was evaluated in an older, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study including 28 children and adolescents, where ziprasidone appeared to be significantly more effective than placebo in reducing tics and was well tolerated.Citation91 A case report described the induction of tardive symptoms in a 28-year-old patient suffering from vocal tics secondary to treatment with ziprasidone. Additionally, anxiety and tension seemed to be aggravated by an increase in the drug. However, vocal tics resolved approximately 4 days after cessation.Citation94

Conclusion

Although the availability of recent data is too restricted to draw a final conclusion, ziprasidone could be used as an attempt if first-line medication was not effective. Apart from QT-prolongation, this drug has a favorable side-effect profile and initial promising results give hope for upcoming studies.

Aripiprazole

Aripiprazole is one of the newest antipsychotics with a unique mechanism of action since it works as a partial agonist on the D2 receptors.Citation22 It also has a high affinity with the serotonin receptor system, working as an antagonistic on 5-HT2A receptors,Citation95,Citation96 and a partial agonistic on 5-HT2C and 5-HT1a receptors.Citation97 Despite the lack of randomized double-blind and placebo-controlled studies, since 2004 more than 200 cases in at least 25 mostly open studies have been published, reporting good efficacy of aripiprazole in the treatment of tics for both adults and children.Citation95,Citation98–Citation120 For instance, one larger retrospective study describes tic reduction in 29 of the 37 patients, who all tolerated the drug and continued the treatment.Citation95 In general, aripiprazole is well tolerated and side effects (insomnia, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, tremor, and agitationCitation121) are usually mild-to-moderate and most often transient. At equivalent doses, aripiprazole is characterized by a safer cardiovascular profile than pimozide.Citation23 Weight gain during treatment with aripiprazole is controversial, however. While some studies report negligible weight gain,Citation101,Citation117 others have described weight increase in 22%Citation95 and up to 50%Citation112 of patients. Murphy and colleaguesCitation115 noticed a mean increase of 2.3 kg after a 6-week trial in an open-label, flexible-dose study with 16 children.

Conclusion

Despite the lack of studies with high methodological standards, the treatment of TS with aripiprazole seems possible to recommend as a second choice, due to its unique mechanism of action, its mostly harmless side-effect profile, and the good clinical experiences reported. At least two studies have judged its effectiveness to be superior to that of previous pharmacological treatment options, even in refractory cases.Citation9,Citation98

Discussion

The importance of neuroleptics in the treatment of tics and TS is illustrated by the fact that haloperidol and pimozide are the only drugs that are approved for therapy of these disorders by the FDA. This approval is based on older trials, however. As our research has shown, the trials representing the basis for the pharmacological treatment of TS with typical antipsychotics are rather old and vary in their results and methodological designs. For example, assessments range from subjective self- rating scales of varying complexity to standardized counting of tics based on video recordings. Furthermore, many studies include both children and adults which often results in the suggestion that both groups should be treated in similar ways, apart from drug dosages. At the same time, many experts prescribe these older drugs rather reluctantly due to the nature of their adverse events, especially when treating the typical patient population which consists of children and younger people. In line with this, the few existing guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of tics and TSCitation9,Citation122–Citation124 and helpful papers with treatment advice and suggested strategiesCitation11,Citation22 mainly recommend the use of atypical antipsychotics as first-line treatment rather than typical neuroleptics. The main reason for this preference for atypical antipsychotics seems to be their different side-effect profiles and their efficacy in the reduction of tic symptoms. But for the example of clozapine, in particular, as the present review shows, it would be wrong to assume this efficacy to be a group effect of antipsychotic agents in general. Among the atypical antipsychotics, risperidone is the best studied agent for the treatment of TS. This, in combination with its positive outcomes, makes this drug, in our and other experts’ opinion, first choice.Citation9,Citation22,Citation124

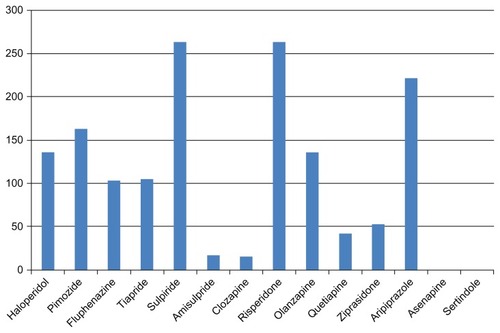

Yet this review of the literature shows that there is currently insufficient evidence-based data on the available second-generation antipsychotics, apart from risperidone (). Maybe the fact that TS in adulthood is a relatively rare disorder could partially explain why the pharmaceutical industry seems to be making only a marginal effort to approve modern antipsychotics for the treatment of TS. This is regrettable especially given the promising results for aripiprazole and olanzapine in methodologically “low level” studies. The efficacy of other promising compounds has not yet been studied either. AsenapineCitation125,Citation126 and sertindoleCitation127 are, based on their mechanism of action, possibly capable of reducing tics. But up to now there is no evidence-based information available on these agents in the treatment of TS. Further research is needed.

Figure 1 Number of patients* with TS, treated with each specific agent in studies and case reports published until May 2011.

The usual fluctuation in both severity and nature of symptoms over time, known as “waxing and waning”, complicates the objective measurement of symptom severity in studies. In addition, it is necessary to know that long-term treatment with neuroleptic, antiepileptic medication, or stimulants can cause tardive TS, which is characterized by the occurrence of multiple motor and vocal tics as well.Citation128 As well as neuroleptics, some experts suggest that alpha-agonists such as clonidine or even guanfacine as first-line therapy have fewer adverse events.Citation129 The existing data for these agents are relatively limited, however, and mainly ascribable to smaller, placebo-controlled studies.Citation130,Citation131 Thus we lack empirical data in support of alpha-agonists, compared with antipsychotics, and on atypical antipsychotics in general. Large, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies and well executed head-to-head comparisons are urgently required, especially those referring to modern, evidence-based criteria. Multicenter studies and independent, well-trained video-raters could be useful to consider larger numbers of patients, and to collect more reliable information on the reduction of Tourette symptoms.

Limitations

The fact that we have only searched PubMed could cause a certain bias in the collection of considered publications, but we assume that all relevant papers are available in PubMed because all highly renowned journals are listed in this database. For many agents presented, the data found were too poor to allow any specific conclusions about a drug. We assume this problem to be caused by the generally limited evidence-based data dealing with TS and tics rather than our search criteria.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO-219 grant) for financial support.

Disclosure

K Hardenacke, P Poppe, B Baskin, and C Bartsch report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest in this investigation. D Huys reports having received financial assistance for travel to congresses from AstraZeneca. J Kuhn has occasionally received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Lilly, Lundbeck, and Otsuka Pharma for lecturing at conferences and financial support to travel to congresses.

References

- MinkJWNeurobiology of basal ganglia and Tourette syndrome: basal ganglia circuits and thalamocortical outputsAdv Neurol200699899816536354

- JankovicJDifferential diagnosis and etiology of ticsAdv Neurol200185152911530424

- WongDFBrasićJRSingerHSMechanisms of dopaminergic and serotengeric neurotransmission in Tourette syndrome: clues from an in vivo neurochemistry study with PETNeuropsychopharmacology20083361239125117987065

- WongDFSingerHSBrandtJD2-like dopamine receptor density in Tourette syndrome measured by PETJ Nucl Med1997388124312479255158

- YoonDYGauseCDLeckmanJFSingerHSFrontal dopaminergic abnormality in Tourette syndrome: a postmortem analysisJ Neurol Sci20072551–2505617337006

- YehCBLeeCHChouYHChangCJMaKHHuangWSEvaluating dopamine transporter activity with 99 mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT in drug-naive Tourette’s adultsNucl Med Commun2006271077978416969259

- YehCBLeeCSMaKHLeeMSChangCJHuangWSPhasic dysfunction of dopamine transmission in Tourette’s syndrome evaluated with (99 m)Tc TRODAT-1 imagingPsychiatry Res20071561758217716877

- GilbertDTreatment of children and adolescents with tics and Tourette syndromeJ Child Neurol200621869070016970870

- RoessnerVPlessenKJRothenbergerAEuropean clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part II: pharmacological treatmentEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry201120417319621445724

- ScahillLErenbergGBerlinCMJrContemporary assessment and pharmacotherapy of Tourette syndromeNeuro Rx20063219220616554257

- SingerHSTreatment of tics and tourette syndromeCurr Treat Options Neurol201012653956120848326

- AzrinNHNunnRGHabit reversal: a method of eliminating nervous habits and ticsBehav Res Ther19731146196284777653

- KuhnJGründlerTOLenartzDSturmVKlosterkötterJHuffWDeep brain stimulation for psychiatric disordersDtsch Arztebl Int2010107710511320221269

- RickardsHHartleyNRobertsonMMSeignot’s paper on the treatment of Tourette’s syndrome with haloperidolHist Psychiatry1997831 Pt 343343611619589

- ParragaHCHarrisKMParragaKLBalenGMCruzCAn overview of the treatment of Tourette’s disorder and ticsJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol201020424926220807063

- ShapiroEShapiroAKFulopGControlled study of haloperidol, pimozide and placebo for the treatment of Gilles de la Tourette’s syndromeArch Gen Psychiatry19894687227302665687

- ShapiroAKShapiroESYoungJGFeinbergTEGilles de la Tourette Syndrome2nd edNew YorkRaven Press1988

- RossMSMoldofskyHA comparison of pimozide and haloperidol in the treatment of Gilles de la Tourette’s syndromeAm J Psychiatry19781355585587347954

- SalleeFRNesbittLJacksonCRelative efficacy of haloperidol and pimozide in children and adolescents with Tourette’s disorderAm J Psychiatry19971548105710629247389

- SandorPMusisiSMoldofskyHLangATourette syndrome: a follow-up studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol19901031971992115892

- BorisonRLAngLHamiltonWJDiamondBIDavisJMTreatment approaches in Gilles de la Tourette syndromeBrain Res Bull19831122052086578865

- EddyCMRickardsHECavannaAETreatment strategies for tics in Tourette syndromeTher Adv Neurol Disord201141254521339906

- GulisanoMCaliPVCavannaAEEddyCRickardsHRizzoRCardiovascular safety of aripiprazole and pimozide in young patients with Tourette syndromeNeurol Sci20113261213121721732066

- PringsheimTMarrasCPimozide for tics in Tourette’s syndromeCochrane Database Syst Rev20092CD00699619370666

- BruggemanRvan der LindenCBuitelaarJKRisperidone versus pimozide in Tourette’s disorder: a comparative double-blind parallel-group studyJ Clin Psychiatry2001621505611235929

- GilbertDLBattersonJRSethuramanGSalleeFRTic reduction with risperidone versus pimozide in a randomized, double-blind, crossover trialJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443220621414726728

- SilayYSVuongKDJankovicJThe efficacy and safety of fluphenazine in patients with Tourette syndromeNeurology200462Suppl 5A506

- JankovicJJimenez-ShahedJBrownLWA randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of topiramate in the treatment of Tourette syndromeJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry2009811707319726418

- BorisonRLAngLChangSDyskenMComatyJEDavisJMNew pharmacological approaches in the treatment of Tourette syndromeAdv Neurol1982353773826756088

- GoetzCGTannerCMKlawansHLFluphenazine and multifocal tic disordersArch Neurol19844132712726582810

- SingerHSGammonKQuaskeySHaloperidol, fluphenazine and clonidine in Tourette syndrome: controversies in treatmentPediatr Neurosci1985–19862127174

- Müller-VahlKRThe benzamides tiapride, sulpiride, and amisulpride in treatment of Tourette’s syndromeNervenarzt200778326427116924461

- DoseMLangeHWThe benzamine tiapride: treatment of extrapyramidal motor and other clinical syndromesPharmacopsychiatry2000331192710721880

- MeiselAWinterCZschenderleinRArnoldGTourette syndrome: efficient treatment with ziprasidone and normalization of body weight in a patient with excessive weight gain under tiaprideMov Disord200419899199215300676

- ScattonBCohenCPerraultGThe preclinical pharmacologic profile of tiaprideEur Psychiatry200116Suppl 129s34s11520476

- BockNMollGHWickerMEarly administration of tiapride to young rats without long-lasting changes in the development of the dopaminergic systemPharmacopsychiatry200437416316715467972

- DrtilkovaIClonazepam, clonidine and tiapride in children with tic disorderHomeostasis1996375216

- KlepelHGebeltHKochRDTzenowHTreatment of extrapyramidal hyperkineses in childhood with tiapridePsychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz)19884095165223070595

- LipcseyAGilles de la Tourette’s diseaseSem Hop198359106956966304891

- EggersCRothenbergerABerghausUClinical and neurobiological findings in children suffering from tic disease following treatment with tiaprideEur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci198823742232292974416

- PaniLGessaGLThe substituted benzamides and their clinical potential on dysthymia and on the negative symptoms of schizophreniaMol Psychiatry20027324725311920152

- YvonneauMBezardPApropos of a case of Gilles de la Tourette’s disease blocked by sulpiride. Psycho-biological studyEncephale19705954394595278253

- RutherEDegnerDMunzelUAntidepressant action of sulpiride. Results of a placebo-controlled double-blind trialPharmacopsychiatry199932412713510505482

- RobertsonMMSchneiderVLeesAJManagement of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome using sulpirideClin Neuropsychopharmacol1990133229235

- HuangTLLuCYCorrelations between weight changes and lipid profile changes in schizophrenic patients after antipsychotics therapyChang Gung Med J2007301263217477026

- WetterlingTMussigbrodtHEWeight gain: side effect of atypical neuroleptics?J Clin Psychopharmacol199919431632110440458

- HoCSChenHJChiuNCShenEYLueHCShort-term sulpiride treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome or chronic tic disorderJ Formos Med Assoc20091081078879319864199

- GeorgeMSTrimbleMRRobertsonMMFluvoxamine and sulpiride in comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder and Gilles-De-La-Tourette syndromeHum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp19938327334

- TrilletMMoreauTDaleryJde VillardRAimardGTreatment of Gilles de la Tourette’s disease with amisulpridePresse Med19901941751968252

- FountoulakisKNIacovidesASt KaprinisGSuccessful treatment of Tourette’s disorder with amisulprideAnn Pharmacother200438590115010520

- KozianRFriedrichMGilles-de-la-Tourette Syndrome as a Tardive DyskinesiaPsychiatr Prax200734525325417597439

- CrillyJThe history of clozapine and its emergence in the US market: a review and analysisHist Psychiatry2007181396017580753

- JaffeETremeauFSharifZReiderRClozapine in tardive Tourette syndromeBiol Psychiatry19953831961977578666

- KalianMLernerVGoldmanMAtypical variants of tardive dyskinesia, treated by a combination of clozapine with propanolol and clozapine with tetrabenazineJ Nerv Ment Dis1993181106496518105027

- CaineEDPolinskyRJKartzinelREbertMHThe trial use of clozapine for abnormal involuntary movement disordersAm J Psychiatry19791363317320154301

- BegumMClozapine-induced stuttering, facial tics and myoclonic seizures: a case reportAust N Z J Psychiatry200539320215701074

- BastiampillaiTDhillonRMohindraRExacerbation of tics secondary to clozapine therapyAust N Z J Psychiatry200842121068107019034993

- KimBNLeeCBHwangJWShinMSChoSCEffectiveness and safety of risperidone for children and adolescents with chronic tic or tourette disorders in KoreaJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200515231832415910216

- van der LindenCBruggemanRvan WoerkomTCSerotonin-dopamine antagonist and Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome: an open pilot dose-titration study with risperidoneMov Disord1994966876887531282

- DiantoniisMRHenryKMPartridgePASoucarETics and risperidoneJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry19963578398408768339

- StamenkovicMAschauerHKasperSRisperidone for Tourette’s syndromeLancet19943448936157715787527115

- ZhaoHZhuYRisperidone in the treatment of Tourette syndromeMent Health J20031730

- ScahillLLeckmanJFSchultzRTKatsovichLPetersonBSA placebo- controlled trial of risperidone in Tourette syndromeNeurology20036071130113512682319

- DionYAnnableLSandorPChouinardGRisperidone in the treatment of tourette syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trialJ Clin Psychopharmacol2002221313911799340

- LimLKShinSYRisperidone versus Haloperidol in the treatment of children with Tourette’s Syndrome and chronic motor or vocal tic disorder in KoreaEur Neuropsychopharacol2006165527

- GaffneyGRPerryPJLundBCBever-StilleKAArndtSKupermanSRisperidone versus clonidine in the treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette’s syndromeJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241333033611886028

- BruunRDBudmanCLRisperidone as a treatment for Tourette’s syndromeJ Clin Psychiatry199657129318543544

- LombrosoPJScahillLKingRARisperidone treatment of children and adolescents with chronic tic disorders: a preliminary reportJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry1995349114711527559308

- ShulmanLMSingerCWeinerWJRisperidone in Gilles de la Tourette syndromeNeurology199545714197542376

- RobertsonMMScullDAEapenVTrimbleMRRisperidone in the treatment of Tourette syndrome: a retrospective case note studyPsychopharmacol1996104317320

- ChappellPBLeckmanJFRiddleMAThe pharmacological treatment of tic disordersChild Adolesc Psychiatric Clin North Am19954197216

- GiakasWJRisperidone treatment for a Tourette’s disorder patient with comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorderAm J Psychiatry19951527109710987540801

- SandorPStephensRJRisperidone treatment of aggressive behavior in children with Tourette syndromeJ Clin Psychopharmacol200020671071211106151

- PappadopulosEWoolstonSChaitAPerkinsMConnorDFJensenPSPharmacotherapy of aggression in children and adolescents: efficacy and effect sizeJ Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2006151273918392193

- StephensRJBasselCSandorPOlanzapine in the treatment of aggression and tics in children with Tourette’s syndrome – a pilot studyJ Child Adolescent Psychopharmacol2004142255266

- BudmanCLGayerALesserMShiQBruunRDAn open-label study of the treatment efficacy of olanzapine for Tourette’s disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200162429029411379844

- McCrackenJTSuddathRChangSThakurSPiacentiniJEffectiveness and tolerability of open label olanzapine in children and adolescents with Tourette syndromeJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200818550150818928414

- http://www.lilly.comZyprexa product label Available from: http://pi.lilly.com/us/zyprexa-pi.pdfAccessed September 28, 2011

- JiWDLiYLiNGuoBYOlanzapine for treatment of Tourette syndrome: a double-blind randomized controlled trialChinese J Clin Rehab200596668

- OnofrjMPaciCD’AndreamatteoGTomaLOlanzapine in severe Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: a 52-week double-blind cross-over study vs low-dose pimozideJ Neurol2000247644344610929273

- Bengi SemerciZOlanzapine in Tourette’s disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039214010673820

- BhadrinathBROlanzapine in Tourette syndromeBr J Psychiatry19981723669715346

- Karam-HageMGhaziuddinNOlanzapine in Tourette’s disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039213910673819

- Lucas TaracenaMTMontanes RadaFOlanzapine in Tourette’s syndrome: a report of three casesActas Esp Psiquiatr200230212913212028946

- KrishnamoorthyJKingBHOpen-label olanzapine treatment in five preadolescent childrenJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol1998821071139730076

- StamenkovicMSchindlerSDAschauerHNEffective open-label treatment of tourette’s disorder with olanzapineInt Clin Psychopharmacol2000151232810836282

- ParragaHCParragaMIWoodwardRLFenningPAQuetiapine treatment of children with Tourette’s syndrome: report of two casesJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200111218719111436959

- MukaddesNMAbaliOQuetiapine treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette’s disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200313329529914642017

- CopurMArpaciBDemirTNarinHClinical effectiveness of quetiapine in children and adolescents with Tourette’s syndrome: a retrospective case-note surveyClin Drug Investig2007272123130

- KeckPEJrMcElroySLArnoldLMZiprasidone: a new atypical antipsychoticExpert Opin Pharmacother2001261033104211585006

- SalleeFRKurlanRGoetzCGZiprasidone treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette’s syndrome: a pilot studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200039329229910714048

- StahlSMShayeganDKThe psychopharmacology of ziprasidone: receptor-binding properties and real-world psychiatric practiceJ Clin Psychiatry200364Suppl 19612

- SalleeFRMiceliJJTensfeldtTRobargeLWilnerKPatelNCSingle-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of ziprasidone in children and adolescentsJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry45672072816721322

- WillmundGLeeAHWertenauerFVocal tics associated with ziprasidoneJ Clin Psychopharmacol200929661161219910734

- BudmanCCoffeyBJShechterRAripiprazole in children and adolescents with Tourette disorder with and without explosive outburstsJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200818550951518928415

- WoodMReavillCAripiprazole acts as a selective dopamine D2 receptor partial agonistExpert Opin Investig Drugs2007166771775

- JordanSKoprivicaVChenRTottoriKKikuchiTAltarCAThe antipsychotic aripiprazole is a potent, partial agonist at the human 5-HT1A receptorEur J Pharmacol2002441313714012063084

- Ben DjebaraMWorbeYSchopbachMHartmannAAripiprazole: a treatment for severe coprolalia in “refractrory” Gilles de la Tourette syndromeMov Disord200815;233438440

- BublEPerlovETebartzVanElstLAripiprazole in patients with Tourette syndromeWorld J Biol Psychiatry20067212312516684686

- ConstantELBorrasLSeghersAAripiprazole is effective in the treatment of Tourette’s disorderInt J Neuropsychopharmacol20069677377416734937

- CuiYHZhengYYangYPLiuJLiJEffectiveness and tolerability of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with Tourette’s disorder: a pilot study in ChinaJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol201020429129820807067

- DaviesLSternJSAgrawalNRobertsonMMA case series of patients with Tourette’s syndrome in the United Kingdom treated with aripiprazoleHum Psychopharmacol200621744745317029306

- DehningSRiedelMMullerNAripiprazole in a patient vulnerable to adverse reactionsAm J Psychiatry2005162362515741488

- DuaneDDAripiprazole in childhood and adolescence for Tourette syndromeJ Child Neurol200621435816900939

- FountoulakisKNSiamouliMKantartzisSPanagiotidisPIacovidesAKaprinisGSAcute dystonia with low-dosage aripiprazole in Tourette’s disorderAnn Pharmacother200640477577716569800

- HoodKKLourivalBNBeasleyPJLobisRPravdovaICase study: severe self-injurious behavior in comorbid Tourette’s disorder and OCDJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2004431012961303

- HounieADe MathisASampaioASMercadanteMTAripiprazole and Tourette syndromeRev Bras Psiquiatr200426321315645072

- Ikenouchi-SugitaAYoshimuraRHayashiKA case of late-onset Tourette’s disorder successfully treated with aripiprazole: view from blood levels of catecholamine metabolites and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)World J Biol Psychiatry2009104 Pt 397798019225990

- KastrupASchlotterWPlewniaCBartelsMTreatment of tics in tourette syndrome with aripiprazoleJ Clin Psychopharmacol2005251949615643108

- KawohlWSchneiderFVernalekenINeunerIAripiprazole in the pharmacotherapy of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome in adult patientsWorld J Biol Psychiatry2009104 Pt 382783118843565

- KawohlWSchneiderFVernalekenINeunerIChronic motor tic disorder and aripiprazoleJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci200921222419622695

- LyonGJSamarSJummaniRAripiprazole in children and adolescents with Tourette’s disorder: an open-label safety and tolerability studyJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200919662363320035580

- MirandaCMCastiglioniTCAripiprazole for the treatment of Tourette syndrome. Experience in 10 patientsRev Med Chil2007135677377617728905

- MurphyTKBengtsonMASotoOCase series on the use of aripiprazole for Tourette syndromeInt J Neuropsychopharmacol20058348949015857570

- MurphyTKMutchPJReidJMOpen label aripiprazole in the treatment of youth with tic disordersJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200919444144719702496

- PadalaPRQadriSFMadaanVAripiprazole for the treatment of Tourette’s disorderPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry20057629629916498492

- SeoWSSungHMSeaHSBaiDSAripiprazole treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette disorder or chronic tic disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200818219720518439116

- WinterCHeinzAKupschAStrohleAAripiprazole in a case presenting with tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Clin Psychopharm2008284452454

- YooHKChoiSHParkSWangHRHongJPKimCYAn open-label study of the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole for children and adolescents with tic disordersJ Clin Psychiatry20076871088109317685747

- YooHKKimJYKimCYA pilot study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with Tourette’s disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200616450550616958578

- PaeCUA review of the safety and tolerability of aripiprazoleExpert Opin Drug Saf20098337338619505266

- Müller-VahlKRRothenbergerARoessnerVPoeweWVingerhoetsFMünchauAGuidelines for diagnosis and treatment: Tic disordersDienerHCPutzkiNGuidelines for Diagnosis and Therapy in NeurologyStuttgart, Thieme2008125129 German

- RothenbergerABanaschewskiTRoessnerVTic disordersGerman Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry PuPGuidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders in Infancy, Childhood and AdolescenceKöln, Deutscher Ärzteverlag2007319325 German

- http://www.dgn.orgGuidelines of the German Society for Neurology Available from: http://www.dgn.org/images/stories/dgn/leitlinien/LL2008/ll08kap_012.pdfAccessed August 12, 2011 German

- ShahidMWalkerGBZornSHWongEHAsenapine: A novel psychopharmacologic agent with a unique human receptor signatureJ Psychopharmacol2009231657318308814

- PompiliMVenturiniPInnamoratiMThe role of asenapine in the treatment of manic or mixed states associated with bipolar I disorderNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2011725926521654871

- AzorinJMKaladjianAFakraEAdidaMSertindole for the treatment of schizophreniaExpert Opin Pharmacother201011183053306421080854

- FountoulakisKNSamaraMSiaperaMIacovidesATardive Tourette-like syndrome: a systematic reviewInt Clin Psychopharmacol201126523724221811171

- JankovicJKurlanRTourette syndrome: evolving conceptsMov Disord20112661149115621484868

- ScahillLChappellPBKimYSA placebo controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorderAm J Psychiatry200115871067107411431228

- CummingsDDSingerHSKriegerMNeuropsychiatric effects of guanfacine in children with mild tourette syndrome: a pilot studyClin Neuropharmacol200225632533212469007