Abstract

Body dysmorphic disorder is a body image dysperception, characterized either by an excessive preoccupation with a presumed or minimal flaw in appearance, or by unrecognition, denial, or even neglect regarding an obvious defect. These features are evaluated by a novel questionnaire, the Brief Assessment of Negative Dysmorphic Signs (BANDS). Moreover, the temperament and character background is examined. The relationship with addictive mentality/behavior and schizoaffectivity is also highlighted. Lastly, the potential shift toward cognitive impairment and dementia is considered.

Introduction

Body dysmorphic disorder is a complex and multifactorial affliction, the clinical features of which vary from an excessive preoccupation with a presumed or minimal flaw in appearance to lack of recognition, denial, or even neglect of an obvious defect.Citation1 The body image appears fragmented, with the “real body”, “perceived body”, “ideal body”, and “socially accepted body” in conflict. Egodystonic features, obsessive-compulsive reactions,Citation2,Citation3 and delusional aspectsCitation1,Citation4 impair quality of life and daily activities, with short-and long-term consequences, worsened by cultural and social factors,Citation1 as well as addictive behaviors.Citation5

Aims and methods

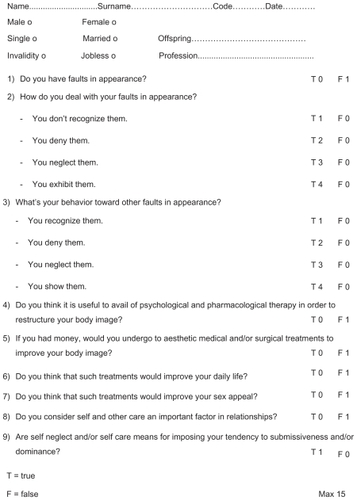

The aim of the present study was directed to identification and scoring of negative psychopathologic features of body dysmorphic disorder. We devised a novel questionnaire, ie, the Brief Assessment of Negative Dysmorphic Signs (BANDS, see ), addressing the presence of faults in own and others’ appearance, the behavioral response toward these faults (lack of recognition, denial, negligence, exhibition), compliance with pharmacologic and aesthetic treatments, their putative success in improving daily life and sex appeal, concern for self-care as an important factor in relationships, and the association of self-care or self-neglect with a tendency to dominance or submissiveness. Moreover, we evaluated early aspects of temperament and character related to the development of body dysmorphic disorder and its worsening because of addictive mentality and/or behaviors. We referred to “Cloninger’s biosocial theory” and administered the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI).Citation6,Citation7 We also used the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Examination (BDDE),Citation8 the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS),Citation9 Michigan Alcoholism Screening test (MAST),Citation10 Munich Alcoholism Test (MAT),Citation11 and Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS).Citation12

Case 1

A 33-year-old craftswoman, with a precarious job and lonely, came to our observation for cranial trauma, followed by two episodes of loss of consciousness with tonic-clonic movements, over a three-day period. She used to drink 0.50–0.75 L of wine with meals and an unspecified quantity of beer during the day. Her physical appearance was neglected (thin, acne) and with some abnormal features (facial down and a tendency to cyphotic posture). She suffered from episodes of migraine and epigastralgia. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 15. Neurologic examination was normal. TCI showed high self-transcendence (29, normal range 15.96 SD 6.14), high harm avoidance (27,18.36 ± 7.01), high persistence (7, 4.54 ± 1.8), low self-directiveness (17, 25.39 ± 7.6), normal novelty seeking (15, 20.58 ± 5.63), reward dependence (16, 16.01 ± 3.35), and cooperativeness (31, 31.43 ± 5). BDDE was 15 and BANDS was 14/15. HDRS score was 22/68 (moderate depression), MAST showed 9/45 positive answers and 2/8 negative answers (alcoholism), and MAT score was 24/52 (alcoholism). DDIS revealed a tendency to dissociative experiences (42 positive and 71 negative answers). Blood examination showed changes in mean corpuscular hemoglobin of 33.9 pg, leucocytes 3.2 × 103, total bilirubin 1.12 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.37 mg/dL, aspartate transminase 286 U/L, alanine transaminase 231 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 113 U/L, and gamma-GT 563 U/L. The electroencephalogram (EEG) showed sporadic central and parietotemporal spikes during hyperventilation and photostimulation. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging were negative. The patient was rehydrated and treated with gabapentin 300 mg, one tablet orally twice daily, vitamin B1 (cocarboxylase) 38 mg, B6 (pyridoxine) 200 mg, B12 (hydroxocobalamin) 1000 mg in 2 mL, metadoxine 500 mg, and omeprazole 40 mg.

Case 2

A 38-year-old unemployed bricklayer came under our care for transient left dystonia, followed by right paresthesia and hyposthenia. He reported that he was born by dystocic delivery. He was a current smoker. He suffered from early baldness, severe caries, and psoriasis, and visual acuity was reduced in the right eye as a result of accidental trauma. He was strongly attached to his family and was single. GCS was 15. Hematologic parameters were altered, ie, erythrocytes 6.71 × 106, mean cell volume 65.5 dL, mean corpuscular hemoglobin 20.9 pg, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration 31.9 g/dL, leucocytes 11.8 × 103, neutrophils 94.4%, lymphocytes 5%, monocytes 0.5%, eosinophils 0.1%, basophils, 0%, and glycemia 144 mg/dL. At urine examination, density was 1033, glucose 100 mg/dL, and proteins 20 mg/dL, with the presence of calcium oxalate. Sinus bradycardia was recorded on ECG. A nonspecific dysregulation was also recorded at EEG. Computed tomography of the brain and encephalic magnetic resonance imaging were negative, with cervical magnetic resonance imaging showing a C3–C4 disc bulge. He was treated with betamethasone 4 mg daily, pentoxiphyllin 400 mg orally, vitamin B1 (cocarboxylase) 38 mg, B6 (pyridoxine) 200 mg, B12 (hydroxocobalamin) 1000 mg in one 2 mL vial daily, and omeprazole 40 mg. Therapy with oral cyclosporine 100 mg, topical calcipotriol, and betamethasone were continued. TCI showed high self-directiveness (36), low harm avoidance (7), and normal reward dependence (18), while scores related to self-transcendence (13), persistence (4), novelty seeking (20), and cooperativeness (27) were at the low limit of normal. BDDE was 11 and BANDS was 12/15.

Case 3

A 44-year-old woman came under our care for schizoaffective symptoms. She had married at the age of 16 as a result of pregnancy and had three children. Her husband had died from an unheralded myocardial infarction. Apparently, she appeared “full of beans”. She did not care about her physical aspect (hooked and deviated nose, slimness). Mitral insufficiency was detected on clinical examination and confirmed by echocardiography. TCI revealed a tendency to low scores for harm avoidance (17), novelty seeking (17), persistence (4), self-directiveness (23), cooperativeness (24), and reward dependence (11), with a high score for self-transcendence (22). BDDE was 3 and BANDS was 13/15. On DDIS, there were 36 positive and 77 negative answers. She was already being followed up by the regional mental health and social services, to which she was referred back with the suggestion to be more compliant with her existing therapeutic and social program, in order to safeguard herself and her children.

Discussion

The present study confirms our previous observations concerning the negative signs of body dysmorphic disorder that are often misdiagnosed, even though they interfere with daily activities and relationships, and can cause or worsen clinical conditions from young adulthood onwards. Social factors, substance abuse disorders (eg, alcoholism)Citation5 and sexual disturbances further worsen body dysmorphic disorder and quality of life. None of the available scales published assess the negative features of body dysmorphic disorder. The proposed novel scale, BANDS, is a useful tool to evaluate and monitor the course of body dysmorphic disorder and its possible shift toward behavioral-cognitive deterioration.

The psychopathologic process is related to the mode of attachment, and early emotional and cognitive experiences.Citation13,Citation14 The consequent development of abnormal aspects of temperament and character may even progress to borderline personality disorder and dissociative experiences.Citation1 The opposite findings are revealed in unmarried females compared wıth males, with high harm avoidance, high self-transcendence, and low self-directiveness being peculiar to women compared with low harm avoidance, high self-directiveness, and a tendency to low levels of self-transcendence and cooperativeness in men.

Self-directiveness is a characteristic reflecting self esteem, discipline, and responsibility, and the capacity for strategic planning and reaching one’s personal goals in a social context. Dysfunction in self-directiveness is linked to irresponsibility, apathy, and a tendency to blame others for personal failure. Although negative experiences of rejection account for self-dysregulation,Citation15 it should be considered that the latter may predispose to them. Often, these negative aspects of personality precede submissiveness, dependency, rumination, and revenge motives. In our unmarried female patient, although high harm avoidance represents a defense mechanism, it may also have been an expression of limited insight. Indeed, addictive behavior was observed, characterized by avoiding responsiveness, reward, and punishment, and abuse of alcohol as a means to cope with negative feelings. These characteristics were further suppressed by high self-transcendence together with a magical ideation on the future. In this case, high persistence may represent an abnormal perseverative responding, described as “obsessive drive” in substance use disorders.Citation16

Smith et al reported that high harm avoidance, low self-directiveness, high self-transcendence, and poor executive functioning are related to schizophrenia endophenotypes.Citation17 In the male case, high self-directiveness, low harm avoidance, and a tendency to low self-transcendence and cooperativeness may be the expression of a narcissistic trait, emotional repression, and internal conflict, which explains the relational closure and chronic activation of stress responses, with consequent somatizations that worsen the psychophysical state. In the third case, negative aspects of personality (low cooperativeness and reward dependence with high self-transcendence) interfered with mental health and social functioning.

In all the cases, body dysmorphic disorder assumed a regressive meaning. As suggested by Phillips et al, treatments should be aimed at improving functioning and quality of life in addition to relieving symptoms.Citation18 In this regard, a cognitive-behavioral approach prompts self-care and assumption of responsibility concerning one’s own life. It stimulates subjects affected by body dysmorphic disorder to rebuild their body image through a strategy that involves three fundamental steps, ie, compliance with therapy, control of risk factors and prevention of diseases and their complications, acceptance of universally shared norms, and behavioral models.

The early diagnosis and care of body image disorders is aimed at offering either short-term or long-term solutions for disorders in youth, which include neuropsychologic support and aesthetic treatment, which is important as an educational tool and as a guide to prevent conduct and behavioral disorders noxious to self and others. The spontaneous human fascination with “synchronicity”Citation19 helps in recovering behavioral harmony through the experience of interpersonal connectedness.Citation20 According to the “circumplex model of personality”, all social interactions are distributed along two orthogonal axes, ie, power/dominance and love/affiliation.Citation21 The need to belong, considered to be a fundamental human motivation,Citation22 is risky without consciousness of self and other feelings and resources, and emotional and social competence, in order to avoid emotional reliance and/or incapacity to discriminate between one’s own and other emotions and sensationsCitation23 with loss of self directiveness.

On the other hand, while solitude represent emotional detachment/dissociation and ambivalence, mental and conduct disorders may develop in adolescence and are reported in teenage pregnancy.Citation24 Moreover, more vocal and prolific tendencies are markers of a suboptimal reproductive social stateCitation25 and of a pseudodemocracy.Citation26 These factors reverse the meaning of the individual and social “niche” in defeat and convert the latter into conflict, destabilizing civil society all over the world. In behavioral variants of frontotemporal dementia, a progressive loss of dominance and increased submissive behaviors are described in cases of predominant involvement of the frontal lobe, while cold-heartedness and lack of empathy are described in the temporal lobe.Citation27 Neuropsychologic and neuroradiologic studies are ongoing to assess whether body dysmorphic disorder represents a dysfunction of the mirror system and is predictive of cognitive diseases.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- FioriPGiannettiLMBody dysmorphic disorder: A complex and polimorphic affectionNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2009547748119777069

- JanetPLes Obsessions et la PsychastenieParigiAlcan1903

- KraepelinECompendium der PsychiatrieLeipzigBarth1908

- JaspersKAllgemeine PsychopathologieBerlinSpringer Verlag1959

- GrantJEMenardWPaganoMEFayCPhillipsKSubstance use disorders in individuals with body dysmorphic disorderJ Clin Psychiatry20056630940515766296

- CloningerCRA systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. A proposalArch Gen Psychiatry1987445735883579504

- CloningerCRSvrakicDMPrzybeckTRA psychobiological model of temperament and characterArch Gen Psychiatry1993509759908250684

- RosenJCReiterJLDevelopment of the Body Dysmorphic Disorder ExaminationBehav Res Ther1996347557668936758

- HamiltonMA rating scale for depressionJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry196023566214399272

- SelzerMLThe Michigan Alcoholism Screening test: The quest for a new diagnostic instrumentAm J Psychiatry1971127165316585565851

- FeuerleinWFRingerCHKufnerHAntonsKDiagnose des the Munich’s test on alcoholismMunch Med Wschr19774012751282

- RossCHeberSNortonGThe Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule: A structured interviewDissociation19892169189

- BowlbyJAttachment and Loss. Volume 1. AttachmentLondonHogarth Press1969

- GiannettiLMNazzaroABalsamoMAgneliFTecniche e Strategie Cognitive-emotional-behavioral techniques and strategiesRome2001

- Smart RichmanLLearyMRReactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism and other forms of interpersonal rejectionPsychol Rev200911636538319348546

- AdinoffBNeurobiologic processes in drug reward and addictionHarv Rev Psychiatry20041230532015764467

- SmithMJCloningerCRHarmsMPCsernanskyJCTemperament and character as schizophrenia endophenotypes in non-psychotic siblingsSchizophr Res200810419820518718739

- PhillipsKAMenardWFayCPaganoMEPsychosocial functioning and quality of life in body dysmorphic disorderCompr Psychiatry20054625426016175755

- StrogatzSHSync: The Emerging Science of Spontaneous OrderNew YorkHyperion2003

- PinelECLongAELandauMJAlexanderKPyszczynskiTSeeing I to I: A pathway to interpersonal connectednessJ Pers Soc Psychol20069024325716536649

- WigginsJSInterpersonal Adjectives ScaleProfessional ManualOdessa, FLPsychological Assessment Resources1995

- BaumeisterRFLearyMRThe need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivationPsychol Bull19951174975297777651

- DecetyJMoriguchiYThe empathic brain and its dysfunction in psychiatric populations: implications for intervention across different clinical conditionsBioPsychoSocial Med20071121

- DwyerJMJacksonTUnwanted pregnancy, mental health and abortion: Untangling the evidenceAust New Zealand Health Policy200851618439247

- FinerLBHenshawSDisparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001Perspect Sex Reprod Health200638909616772190

- RaineTRGardJCBoyerCBContraceptive decision-making in sexual relationships: Young men’s experiences, attitudes and valuesCult Health Sex20101237338620169479

- RankinKPKramerJHMychackPMillerBLDouble dissociation of social functioning in fronto-temporal dementiaNeurology20036026627112552042