Abstract

Background

The Prospective Epidemiological Research on Functioning Outcomes Related to Major Depressive Disorder (PERFORM) study has been initiated to better understand the course of a depressive episode and its impact on patient functioning. This analysis aimed to identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with failure to achieve remission at month 2 after initiating or switching antidepressant monotherapy and with subsequent relapse at month 6 for patients in remission at month 2.

Materials and methods

This was a 2-year observational cohort study in 1,159 outpatients aged 18–65 years with major depressive disorder initiating or undergoing the first switch of antidepressant monotherapy. Factors with P<0.20 in univariate logistic regression analyses were combined in a multiple logistic regression model to which backward variable selection was applied (ie, sequential removal of the least significant variable from the model and recomputation of the model until all remaining variables have P<0.05).

Results

Baseline factors significantly associated with lower odds of remission at month 2 were body-mass index ≥30 kg/m2 (OR 0.51), depressive episode >8 weeks (OR 0.51), being in psychotherapy (OR 0.51), sexual dysfunction (OR 0.62), and severity of depression (OR 0.87). Factors significantly associated with relapse at month 6 were male sex (OR 2.47), being married or living as a couple (OR 2.73), residual patient-reported cognitive symptoms at 2 months (OR 1.12 per additional unit of Perceived Deficit Questionnaire-5 score) and residual depressive symptoms at 2 months (OR 1.27 per additional unit of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score).

Conclusion

Different factors appear to be associated with failure to achieve remission in patients with major depressive disorder and with subsequent relapse in patients who do achieve remission. Patient-reported cognitive dysfunction is an easily measurable and treatable characteristic that may be associated with an increased likelihood of relapse at 6 months in patients who have achieved remission.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a chronic and recurring condition that affects more than 120 million people worldwide and ranks among the top ten causes of global disability.Citation1,Citation2 Patients with MDD report substantial deficits in daily functioningCitation3 that equal or exceed those associated with other severe chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes and congestive heart failure.Citation4 Multiple domains of functioning may be impaired;Citation4 consequently, MDD can have a significant impact on both quality of life and work productivity.Citation5,Citation6

In terms of clinical management of MDD, the primary objective is to achieve remission. However, despite therapeutic advances, a considerable proportion of patients fail to achieve this goal. Meta-analyses of results of controlled clinical trials have generally shown remission rates of 30%–50% after 6–8 weeks of treatment with currently available antidepressants.Citation7–Citation12 Remission rates are even lower in routine practice settings. In the US STAR*D study – a large trial designed to assess the efficacy of sequential acute treatments for MDD – only 30%–40% of patients achieved remission after adequate treatment with a first-line antidepressant.Citation13,Citation14 In addition, approximately a third of patients failed to achieve remission after trials of as many as four different antidepressants.Citation14 A 12-week remission rate of 31.4% was reported in the South Korean Clinical Research Centre for Depression study.Citation15 Beyond its clinical consequences, failure to achieve remission in MDD is associated with subsequently higher annual health-care resource utilization and expenditure.Citation16–Citation19

For patients who have achieved remission, the objective of clinical management is to prevent relapse. However, prevention of relapse in patients who achieve remission is also a challenge for current treatments. In STAR*D, the 6-month relapse rate was 34%–83%, depending on the phase of treatment.Citation13 Patients who relapse within 6 months of remission have been shown to have a far worse course of depression over the next 5 years than those who do not relapse within this period of time, as indicated by a significantly greater proportion of time spent with higher levels of severity of depressive symptoms and fewer asymptomatic weeks.Citation20

Awareness of sociodemographic or clinical factors that may be associated with failure to achieve remission in patients with MDD or with an increased risk of subsequent relapse in patients who do achieve remission may help to improve clinical management by enabling identification of patients who may require more intensive follow-up and care. Sociodemographic factors that have previously been reported to be associated with failure to achieve remission of MDD include sex,Citation21,Citation22 educational level,Citation21,Citation23 employment status,Citation21,Citation23 and marital status;Citation24 clinical factors include depression severity in the acute phase,Citation25,Citation26 concomitant mental or chronic medical disorders,Citation21,Citation22 and lower functioning and quality of life at baseline.Citation21,Citation24 Factors that have been reported to be associated with relapse in patients with MDD include chronicity (ie, presence of previous depressive episodes)Citation27,Citation28 and presence of residual mood symptoms.Citation29 Many studies have been undertaken to identify factors that may be associated with poor treatment outcomes in MDD; however, the majority of these have been in highly selected patient populations, which may limit generalization of the findings to routine clinical practice.

The Prospective Epidemiological Research on Functioning Outcomes Related to Major Depressive Disorder (PERFORM) study is an observational cohort study initiated to better understand the course of a depressive episode and its impact on patient functioning over a 2-year period in outpatients with MDD in real-world settings in five European countries. This paper reports planned analyses undertaken to examine potential sociodemographic or clinical factors associated with failure to achieve remission at month 2 and with subsequent relapse at month 6 for patients in remission at month 2. Factors explored included those previously identified in the literature and others, such as cognitive symptoms, which have been identified more recently as relevant in the course of depression and thus have been less extensively studied to date.Citation30,Citation31

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a 2-year multicenter, prospective, noninterventional cohort study in outpatients aged 18–65 years with a current diagnosis of MDD (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM]-IV-TR) enrolled by either a primary care physician or a psychiatrist in France, UK, Spain, Germany, and Sweden. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01427439). Enrolled patients were either initiating antidepressant monotherapy or undergoing their first switch of antidepressant for a new episode of major depression, with the choice of antidepressant used based on the clinical judgment of the treating physician. Patients receiving antidepressant combination therapy at the time of the initial consultation and patients with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, substance dependence, mood disorders due to a general medical condition or substances, dementia, or other neurodegenerative diseases significantly impacting cognitive functioning were excluded from study entry. Pregnant women and women ≤6 months’ postpartum were also excluded.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained for each study site before study initiation following country regulations regarding observational studies:

France: French health authority (ANSM, previously called AFSSAPS), advisory committee on information processing in material research in the field of health (CCTIRS), French data-protection agency (CNIL), French National Medical Council (CNOM) Ethics Committee (CPP Ile de France II); 102 physicians/sites included

Germany: Munich Ethics Committee, local ethics committees, including Hamburg, Rheinland-Pfalz, Sachsen, and Westfalen-Lippe ethics committees and others; 47 physicians/sites included

Spain: Agencia Española del Medicamento y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS), Comités Eticos de Investigaciones Clinicas (CEIC), Comunidades Autónomas (CCAA) of 14 regions; 46 physicians/sites included

Sweden: Uméå Ethics Committee; 22 physicians/sites included

UK: Medical Research and Ethics Committee (MREC), National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and local submissions; 65 physicians/sites included.

All patients provided written informed consent for participation.

Study assessments and data collection

Study assessments and data collection occurred during routine visits within the normal course of care at baseline, 2 months (±3 weeks), and 6 months (±1 month), after which data were collected approximately every 6 months up to 2 years. Patient characteristics recorded included demographic information, history of MDD, characteristics of the current episode of depression, MDD management and resource use, and the presence of any other mental disorder or functional syndrome.

Clinical severity of depression was assessed at all visits by patients using the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)Citation32 and by all participating investigators using the Clinical Global Impressions–severity of illness scale (CGI-S).Citation33 The Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)Citation34 was also administered when patients were recruited by psychiatrists. Patient-reported cognitive function was assessed using the five-item Perceived Deficit Questionnaire (PDQ-5), which assesses subjective cognitive symptoms (impairments in memory, concentration, and executive function) over the past 4 weeks.Citation35,Citation36 Total score range is 0–20, with higher scores reflecting greater impairment.

Psychiatrists also assessed the severity of anxiety symptoms using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale.Citation37 Other patient-reported questionnaires administered included the Sheehan Disability Scale,Citation38 the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire,Citation39 the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12),Citation40 the EuroQol questionnaire (EQ-5D three-level version; in UK patients only),Citation41 the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale,Citation42 and the four-item Morisky–Green Medication Adherence Scale.Citation43

Outcomes

The primary definition of remission at the 2-month visit was PHQ-9 total score ≤9.Citation32 If PHQ-9 score was missing, then MADRS total score was used for patients recruited by psychiatrists; remission was defined as a MADRS score ≤10.Citation44,Citation45 If MADRS score was missing, then remission was defined as a CGI-S score ≤2.Citation46 For patients in remission at 2 months, relapse at the 6-month visit was defined as: (i) treatment modification (switch or combination) for lack of efficacy at the 6-month visit;Citation47 or (ii) PHQ-9 total score ≥10 at the 6-month visit,Citation32 or MADRS total score ≥22 at the 6-month visit if PHQ-9 was missing,Citation48 or CGI-S score ≥4 at the 6-month visit if PHQ-9 and MADRS were missing.Citation48 Relapse status was classified as ambiguous for patients who met criteria for both remission and relapse at month 6 or who were neither remitters nor relapsers at month 6 (eg, MADRS score of 11–21 if PHQ-9 was missing or CGI-S score of 3 if PHQ-9 and MADRS were missing).

Statistical analysis

The population for analysis comprised all patients who met study inclusion criteria and for whom at least one postbase-line assessment was recorded. Clinically relevant variables recorded at baseline were tested in univariate logistic regression analyses for association with failure to achieve remission at month 2. Clinically relevant variables recorded at baseline and/or at or up to month 2 were tested in univariate logistic regression analyses for association with subsequent relapse at month 6 in patients who achieved remission at month 2. The variables included in these univariate analyses were selected based on literature review and clinical evaluation (). Variables with P<0.20 in the univariate analyses were then combined in a multiple logistic regression model to which backward variable selection was applied (ie, sequential removal of the least significant variable from the model and recomputation of the model until all remaining variables had P<0.05). Four factors were forced into the model as adjustment variables because they were identified as potential confounders: country, age, sex, and PHQ-9 total score (at baseline for the remission analysis and at month 2 for the relapse analysis).

Table 1 Variables selected for univariate analyses to identify factors associated with remission at month 2 and relapse at month 6 for patients in remission at month 2

Results are presented as ORs with 95% CIs. By default, ORs for assessment scales and for continuous outcomes are given per additional unit. To account for the differences in metrics between scales, ORs for assessment scales were also estimated per additional 0.5 SD to provide a standardized measure and enable comparisons between scales. Supportive analyses were performed by using a forward-selection process instead of backward selection. In addition, for the analysis of factors associated with relapse, alternative definitions for remission and relapse were used to investigate the effect of the PHQ-9 thresholds applied in the study. Alternative definitions included reducing the cutoff used to define remission, placing MADRS before PHQ-9 in the composite definition of remission, increasing the cutoff used to define relapse, and imposing a defined minimum change in PHQ-9 score. These later analyses were conducted using the final model identifying factors associated with relapse at month 6 for patients in remission at month 2 obtained by backward selection. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, US).

Results

Patients

A total of 1,895 patients were screened, of whom 1,402 were enrolled in the study. The first patient was screened on February 25, 2011, and the last patient completed the study on February 19, 2015. In all, 1,159 (82.7%) patients were included in the population for analysis. Reasons for exclusion from the analysis population were violation of at least one of the inclusion and/or exclusion criteria at baseline (n=167) or lack of postbaseline data (n=101, including 76 who met the inclusion criteria at baseline). The majority of patients were enrolled and followed up by primary care physicians (n=969; 83.6%). At the start of the study, 78.7% of patients were initiating antidepressant treatment and 21.3% were switching antidepressant; the treatment status of two patients was unknown.

Remission status was available for 1,112 of the 1,120 patients who attended a month 2 visit (99.3%). Of these 1,112 patients, 330 were in remission (29.7%). Of the 330 patients in remission at month 2, 300 had known relapse status at month 6 (90.9%). Of those, 59 (19.7%) had relapsed at month 6, 226 (75.3%) were in sustained remission, and remission status was ambiguous for 15 (5.0%). and present baseline data for the different study subpopulations.

Table 2 Baseline sociodemographic characteristics for subsets of patients by remission status at month 2 and by relapse status at month 6 in those who achieved remission at month 2

Table 3 Medical profile, functioning, and quality of life at baseline for subsets of patients by remission status at month 2 and by relapse status at month 6 in those who achieved remission at month 2

Factors associated with failure to achieve remission at month 2

Statistically significant results (P<0.05) were observed for 18 of the 30 factors of interest included in the univariate analyses (): switch of antidepressant, body-mass index (BMI), tobacco use, educational level, time since beginning of this depressive episode, at least one other concomitant mental disorder, chronic pain or fibromyalgia, hospitalization for depression during the 12 weeks before baseline, suicide attempt before baseline, sick leave during the 12 months before baseline, current psychotherapy, PHQ-9 total score, PDQ-5 total score, CGI-S score, percentage activity impairment due to problem, SF-12 physical component summary (PCS), SF-12 mental component summary (MCS), and sexual dysfunction. Living area and at least one chronic medical condition were not statistically significant in univariate analyses; however, since the P-values for these factors were below 0.20, they were also included in the multivariate analysis.

In addition to the four forced adjustment factors (country, age, sex, and PHQ-9 total score at baseline), the final multivariate analysis model retained four factors with P<0.05 from the backward-selection process: BMI, time since beginning of this depressive episode, current psychotherapy, and sexual dysfunction (). Among the forced factors, country and PHQ-9 total score were statistically significant.

Table 4 Multivariate logistic regression model for analysis of risk factors of failure to achieve remission at month 2 (backward selection)

The odds of achieving remission at month 2 were significantly lower for obese patients (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), patients with a longer time since the beginning of the depressive episode (>8 weeks vs <4 weeks), patients who were in psychotherapy at the beginning of the study, and patients who had sexual dysfunction. The odds of achieving remission at month 2 were 13% less likely when the PHQ-9 total score increased by 1 unit (P<0.001) and 30% less likely when PHQ-9 total score increased by 0.5 SD (2.6 units). As ORs cannot be interpreted as relative risks, these figures are provided only to gain a better understanding of the size of the effect.

The results of the supportive analysis using the forward-selection process were consistent with those obtained using the backward-selection process (base-case analysis). In particular, the same factors were retained by both selection processes. The only factor among those initially selected that had a P-value between 0.05 and 0.10 when removed from the multivariate models during the backward-selection process was suicide attempt before baseline (P=0.0624) ().

Factors associated with relapse at month 6

Statistically significant results (P<0.05) were observed for six of the 30 variables of interest selected to perform the univariate analyses (): marital status, PHQ-9 total score, PDQ-5 total score, percentage activity impairment due to problem, SF-12 MCS, and suicide attempt (before baseline or between baseline and month 2). CGI-S, SF-12 PCS, and switch of antidepressant (at baseline, between baseline and month 2, or at month 2) were not statistically significant in univariate analyses, but were included in the multivariate analysis (P<0.20).

In addition to the four forced adjustment factors (country, age, sex, and PHQ-9 total score at month 2), the final multivariate analysis model retained two factors with P<0.05 from the backward-selection process: marital status and PDQ-5 total score at month 2 (). Among the forced factors, sex and PHQ-9 total score were statistically significant.

Table 5 Multivariate logistic regression model for analysis of risk factors of relapse at month 6 for patients in remission at month 2 (backward selection)

The odds of experiencing relapse at month 6 were significantly higher for male patients and patients who were married or living as a couple. Each additional unit of PDQ-5 total score (range 0–20) at 2 months was associated with a 12% increase in the odds of relapse at 6 months (P=0.042). Each additional unit of PHQ-9 total score (range 0–27) at 2 months was associated with a 27% increase in the odds of relapse at 6 months (P=0.030). The standardization process to account for the difference in metrics between the two scales showed an additional 0.5 SD in PDQ-5 total score (2.16 units) and PHQ-9 total score (1.18 units) at 2 months to be associated with a similar increase in the odds of relapse at 6 months.

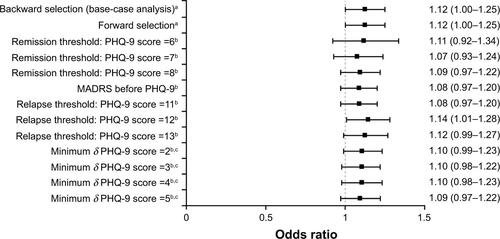

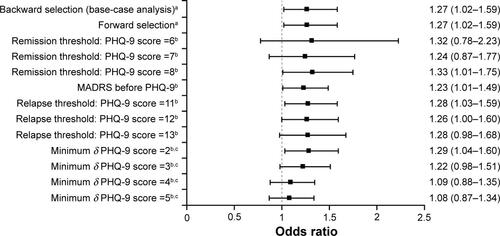

The results of the supportive analysis using a forward-selection process were identical to those obtained using the backward-selection process (base-case analysis). The same factors were retained by both selection processes. The ORs for association with PDQ-5 and PHQ-9 scores were consistent across all alternative definitions of remission and relapse tested, ranging from 1.07–1.14 and 1.08–1.33, respectively ( and ). The only two factors among those initially selected that had P-values between 0.05 and 0.10 when they were removed from the multivariate models during the backward-selection process were suicide attempt before baseline or up to month 2 (P=0.0844) and SF-12 PCS score at month 2 (P=0.0667) ().

Discussion

Results of this study suggest that different sociodemographic and clinical factors may be associated with failure to achieve remission compared with relapse in patients with MDD. Baseline sociodemographic and clinical factors that appeared to be associated with a reduced likelihood of achieving remission at month 2 were severity of depression (assessed by PHQ-9 total score), obesity, longer duration of depression, being in psychotherapy, and sexual dysfunction. The finding that baseline severity of depression and longer duration of depression were associated with the likelihood of remission was expected.Citation15,Citation21,Citation68 Other studies have also suggested that overweight or obese patients may be less likely to achieve remission of MDD.Citation50

The finding that baseline sexual dysfunction increased the likelihood of failing to achieve remission was more unexpected. Although sexual dysfunction is known to be linked to serotonergic neurotransmission and to be associated with depression and antidepressant treatment, sexual dysfunction may also be a trigger for depression.Citation69,Citation70 Our finding could support this hypothesis. If sexual dysfunction plays a role in the onset of depression, then it is reasonable to assume that it will be associated with the prognosis; however, this clearly requires confirmation in further studies. In patients on antidepressant therapy, low adherence related to treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction can also be hypothesized.Citation69,Citation71

The finding that current psychotherapy was associated with a lower likelihood of remission at 2 months was also unexpected. However, in the context of this analysis, being in psychotherapy should be considered as a patient characteristic indicating chronicity of depression or more complex disease (such as double depression or depression associated with personality disorders), rather than as a treatment intervention. This was supported by results of complementary analyses undertaken to explore this finding (). The observed association between country and likelihood of achieving remission is difficult to interpret, as it might stem from many different sources, including differences in clinical practice among participating countries, such as differences in the proportion of patients treated by psychiatrists and the type of antidepressant received.

Factors that appeared to be associated with an increased likelihood of relapse at month 6 in patients in remission at month 2 in this study were male sex, being married or living as a couple, residual depressive symptoms, and residual patient-reported cognitive symptoms. The role of sex as a factor associated with relapse in MDD remains uncertain, with previous studies yielding conflicting data.Citation21,Citation22,Citation27,Citation64 The relationship between marital status and depression is also complex; however, previous studies have shown low relationship satisfaction to be a risk factor for depression, which might explain the observed association between being married or living as a couple and relapse in this study.Citation72–Citation74

With regard to the association of higher PHQ-9 total score with increased likelihood of relapse, it is well documented that residual depressive symptoms after remission are associated with an increased risk of subsequent relapse in patients with MDD.Citation29,Citation66,Citation75 It is not known how cognitive symptoms may influence clinical outcome in patients with MDD. Recent data suggest that cognitive impairment is a frequent residual symptom of MDD and a principal mediator of occupational impairment in patients in remission.Citation76,Citation77 Residual cognitive symptoms may also lead to persistent psychosocial impairment, or cognitive dysfunction may be associated with a cognitive affective bias.Citation30 Cognitive symptoms might also impair adherence to treatment; however, data on this topic are lacking.

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that residual patient-reported cognitive symptoms may be associated with subsequent relapse in patients with MDD. In this analysis, each additional unit of PDQ-5 total score at month 2 was associated with a 12% increase in the odds of relapse at month 6. The magnitude of effect for residual patient-reported cognitive symptoms at month 2 was comparable to that of depressive symptoms at month 2 when expressed in terms of a change of 0.5 SD to account for the difference in metrics between the PDQ-5 and PHQ-9 scales (range 0–20 and 0–27, respectively). The extensive control for known factors associated with relapse in the final model and the supportive analyses demonstrate the consistency of these findings. These results need to be confirmed in further studies using objective tests of cognitive function. However, these findings suggest a role for assessment of cognitive function – even with simple questions and in all settings, including primary care practices – to identify patients at higher risk of subsequent relapse after remission of MDD. While these results confirm that residual mood symptoms are a good target for detection of patients at risk of relapse of MDD,Citation78,Citation79 they also imply that therapeutic interventions that reduce residual cognitive dysfunction in patients with MDD who achieve remission could potentially lead to reduced risk of relapse. However, this requires confirmation in further studies before definitive recommendations can be made.

In this study, the remission rate at month 2 was 29.7%; this is lower than typically reported in clinical trial settings, but is in line with the remission rate reported in more naturalistic studies, such as STAR*D.Citation13 The relatively low remission rate highlights the fact that achieving remission is still a major unmet need for patients with MDD. The relapse rate at 6 months in this study was 19.7%, which is lower than that reported in STAR*D.Citation13 However, this may be at least in part due to the fact that there was only a 4-month interval between assessment of remission and relapse in this study; relapse rates are more typically assessed up to 6 months after achieving remission in clinical trials. An interesting next step will be to analyze relapse rates over longer follow-up.

Remission and relapse needed to be precisely defined in this study. Composite definitions relying on several different assessments were used to increase the likelihood of capturing remission and relapse, and to minimize the impact of missing data. PHQ-9 total score was chosen as the first criterion for these composite definitions. The PHQ-9 is a brief, self-administered questionnaire specifically developed for evaluation of the severity of depressive symptoms,Citation32 and is widely used in both research settings and clinical practice. PHQ-9 total score was assessed for all patients in the study, regardless of the setting (primary or specialized care). The second criterion used was MADRS total score.Citation34 The MADRS is widely used to assess depression severity in randomized clinical trials of antidepressant therapy.Citation80,Citation81 This scale requires training to ensure reliable scoring, and was thus administered only by psychiatrists in this study; however, the majority of patients (83.6%) were enrolled and followed up by general practitioners. The investigator-administered CGI-S was the final criterion for the composite definitions of remission and relapse; however, CGI-S score was only used if data were unavailable for both of the previous scales, as this assessment scale is not specific for depression. The composite definition of relapse included an additional criterion related to need for treatment modification for lack of efficacy at the 6-month visit. This criterion was added to capture the clinical evaluation of the physician, and is commonly used in definitions of relapse in relapse-prevention clinical trials.

Cutoff values for remission based on MADRS and CGI-S scores are well established.Citation44-Citation46,Citation82 In contrast, several different cutoff values have been proposed for remission on the PHQ-9 scale. A PHQ-4 total score <5 has been used to define remission in some observational studies.Citation56,Citation83,Citation84 However, this is based on the theoretical absence of depressive symptoms at this score, rather than an accepted definition of remission.Citation32,Citation85 Validation studies of the PHQ-9 scale established a score of 10 or higher as the cutoff for a diagnosis of depression.Citation32 A recent meta-analysis found the PHQ-9 to have acceptable diagnostic properties for detecting MDD for cutoff scores between 8 and 11.Citation86 However, the scale was found to be sensitive to clinical setting, which could affect the number of false positives and thus necessitate adapting the PHQ-9 cutoff used for remission in individual studies. Available data indicate an optimal threshold to define remission of between 7 and 12 on the PHQ-9 when compared with the CGI-S, and between 9 and 13 when compared with the MADRS, supporting the selected cutoff of 9 for the definition of remission used in this study. Indeed, this cutoff value has been used in other studies.Citation87,Citation88 With this definition, there is no gap between remission and relapse on the PHQ-9. To test if this induces a risk of misclassification of patients that could lead to biased estimates, additional supportive analyses using alternative definitions of remission and relapse were undertaken for the current study; using different thresholds yielded similar ORs for PDQ-5 and PHQ-9 effect at month 6.

A key strength of this study is that it was performed in a real-world setting with longitudinal follow-up of a large cohort of patients, the majority of whom were enrolled and followed up by primary care physicians. This suggests that the study findings are applicable to routine clinical practice, where patients with MDD are typically treated in primary care settings. In addition, the analysis was based on variables identified from a literature review as being clinically relevant factors. The literature review yielded concepts and notions that we tried to capture using available PERFORM data. For example, substance abuse is captured both by the tobacco-use covariate and the concomitant mental disorder covariate. Some variables were added to the list of covariates, as they were considered important for the outcome of the disease (eg, disease management and important life events). Country, age, sex, and PHQ-9 total score (at baseline for the remission analysis and at month 2 for the relapse analysis) were forced into the model as adjustment variables, because they were identified as potential confounders. The effects of treatment in the study population were addressed via covariates reflecting the type of treatment (psychotherapy) and meaningful treatment patterns (treatment switch, treatment stop, and line of treatment). The drug received was not taken into account, as the study design and data-collection method did not allow for assessment of treatment effect.

A potential limitation is the fact that the PHQ-9 is completed by patients, while the MADRS and CGI-S are completed by physicians, which may have introduced differences in estimation of rates of remission and relapse between the different measures. For analysis of factors associated with relapse in patients who were in remission at month 2, fewer variables were selected from the univariate analysis; this is most likely due to the relatively limited sample size. Nevertheless, results of the supportive analyses using the forward-selection process were consistent with the ORs obtained using the backward-selection process, confirming the robustness of the statistical model. Regarding relapse, it is important to note that this study was observational and differs in design from relapse-prevention trials. In particular, there was only a 4-month interval between assessment of remission and relapse in this study. In addition, cognitive dysfunction was assessed using a patient-reported questionnaire, and little has been published regarding the extent to which PDQ-5 score reflects or is correlated with objective measures; however, this is relevant from a routine-practice perspective, as objective neuropsychological tests are not used in primary care settings.

Conclusion

In summary, results of this large observational study suggest that certain sociodemographic and clinical characteristics may be associated with an increased likelihood of failure to achieve remission in patients with MDD or with subsequent relapse in patients who do achieve remission. In particular, cognitive dysfunction appears to be an easily measurable patient characteristic that may be associated with an increased likelihood of relapse at 6 months in patients who have achieved remission. This finding suggests that therapeutic interventions that reduce residual cognitive dysfunction in patients who achieve remission could lead to a reduced risk of relapse of MDD. Further studies are needed to confirm this and to provide evidence on the magnitude of the effect and its importance for clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Lundbeck SAS. The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the physicians and patients who kindly provided data for the study. Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Jennifer Coward of Anthemis Consulting Ltd, funded by Lundbeck SAS. The authors also thank MAPI Registrat for the logistical management of the study.

Supplementary materials

Figure S1 Summary of supportive analyses of PDQ-5 effect on relapse at month 6.

Notes: aComputed for patients with complete values on all candidate variables (n=186); bcomputed for patients with complete values on all variables in the final model (n=193); cadditional criterion for relapse definition: minimum change in PHQ-9 total score between month 2 and month 6. Values expressed as OR (95% CI).

Abbreviations: MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; PHQ-9, 9-item Public Health Questionnaire.

Figure S2 Summary of supportive analyses of PHQ-9 effect on relapse at month 6.

Notes: aComputed for patients with complete values on all candidate variables (n=186); bcomputed for patients with complete values on all variables in the final model (n=193); cadditional criterion for relapse definition: minimum change in PHQ-9 total score between month 2 and month 6. Values expressed as OR (95% CI).

Abbreviations: MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; PHQ-9, 9-item Public Health Questionnaire.

Table S1 Details of backward-selection process for analysis of factors associated with remission at month 2

Table S2 Details of backward-selection process for analysis of factors associated with relapse at month 6 for patients in remission at month 2

Table S3 Complementary analysis comparing factors identified as potential indicators of severity and chronicity of depression according to psychotherapy at baseline

Disclosure

JMH has received honoraria for being an advisor or providing education talks for Lundbeck, Otsuka, Roche, and Eli Lilly and Company. BJ has received honoraria for being an advisor to Lundbeck. MK has received consultancy funding from Lundbeck and Takeda, and has received research funding from Lundbeck. DS and BR are full-time employees of Lundbeck SAS. MT is a full-time employee of Lundbeck LLC. At the time the study was conducted, BB was an employee of Inferential, which received funding from Lundbeck SAS, and his current affiliation is Innovus Consulting Ltd, London, UK. IF and HL are full-time employees of H Lundbeck AS. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KesslerRCBirnbaumHGShahlyVAge differences in the prevalence and co-morbidity of DSM-IV major depressive episodes: results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey InitiativeDepress Anxiety201027435136420037917

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 CollaboratorsGlobal, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013Lancet2015386999574380026063472

- KesslerRCBerglundPDemlerOThe epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R)JAMA2003289233095310512813115

- McKnightPEKashdanTBThe importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: a case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment researchClin Psychol Rev200929324325919269076

- KennedySHEisfeldBSCookeRGQuality of life: an important dimension in assessing the treatment of depression?J Psychiatry Neurosci200126SupplS23S2811590966

- KatonWThe impact of depression on workplace functioning and disability costsAm J Manag Care20091511 SupplS322S32720088628

- KennedySHAndersenHFThaseMEEscitalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysisCurr Med Res Opin200925116117519210149

- ThaseMEEntsuahARRudolphRLRemission rates during treatment with venlafaxine or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitorsBr J Psychiatry200117823424111230034

- ThaseMEPritchettYLOssannaMJSwindleRWXuJDetkeMJEfficacy of duloxetine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: comparisons as assessed by remission rates in patients with major depressive disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol200727667267618004135

- ThaseMEKornsteinSGGermainJMJiangQGuico-PabiaCNinanPTAn integrated analysis of the efficacy of desvenlafaxine compared with placebo in patients with major depressive disorderCNS Spectr200914314415419407711

- ThaseMENierenbergAAVrijlandPvan OersHJSchutteAJSimmonsJHRemission with mirtazapine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 15 controlled trials of acute phase treatment of major depressionInt Clin Psychopharmacol201025418919820531012

- ThaseMEMahableshwarkarARDragheimMLoftHVietaEA meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of vortioxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adultsEur Neuropsychopharmacol201626697999327139079

- RushAJTrivediMHWisniewskiSRAcute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D reportAm J Psychiatry2006163111905191717074942

- WardenDRushAJTrivediMHFavaMWisniewskiSRThe STAR*D project results: a comprehensive review of findingsCurr Psychiatry Rep20079644945918221624

- KimJMKimSWStewartRPredictors of 12-week remission in a nationwide cohort of people with depressive disorders: the CRESCEND studyHum Psychopharmacol2011261415021344501

- MauskopfJASimonGEKalsekarANimschCDunayevichECameronANonresponse, partial response, and failure to achieve remission: humanistic and cost burden in major depressive disorderDepress Anxiety2009261839718833573

- ByfordSBarrettBDespiégelNWadeAImpact of treatment success on health service use and cost in depression: longitudinal database analysisPharmacoeconomics201129215717021142289

- KubitzNMehraMPotluriRCGargNCossrowNCharacterization of treatment resistant depression episodes in a cohort of patients from a US commercial claims databasePLoS One2013810e7688224204694

- DennehyEBRobinsonRLStephensonJJImpact of non-remission of depression on costs and resource utilization: from the comorbidities and symptoms of depression (CODE) studyCurr Med Res Opin20153161165117725879140

- JuddLLSchettlerPJRushAJA brief clinical tool to estimate individual patients’ risk of depressive relapse following remission: proof of conceptAm J Psychiatry2016173111140114627418380

- TrivediMHRushAJWisniewskiSREvaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practiceAm J Psychiatry20061631284016390886

- CheungAAnxiety as a predictor of treatment outcome in children and adolescents with depressionJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol201020321121620578934

- BarkowKMaierWUstünTBGänsickeMWittchenHUHeunRRisk factors for depression at 12-month follow-up in adult primary health care patients with major depression: an international prospective studyJ Affect Disord2003761–315716912943946

- WeinbergerMISireyJABruceMLHeoMPapademetriouEMeyersBSPredictors of major depression six months after admission for outpatient treatmentPsychiatr Serv200859101211121518832510

- O’LearyDCostelloFGormleyNWebbMRemission onset and relapse in depression: an 18-month prospective study of course for 100 first admission patientsJ Affect Disord2000571–315917110708827

- KatonWUnützerJRussoJMajor depression: the importance of clinical characteristics and treatment response to prognosisDepress Anxiety2010271192619798766

- McGrathPJStewartJWQuitkinFMPredictors of relapse in a prospective study of fluoxetine treatment of major depressionAm J Psychiatry200616391542154816946178

- ten DoesschateMCBocktingCLKoeterMWScheneAHPrediction of recurrence in recurrent depression: a 5.5-year prospective studyJ Clin Psychiatry201071898499120797379

- NierenbergAAHusainMMTrivediMHResidual symptoms after remission of major depressive disorder with citalopram and risk of relapse: a STAR*D reportPsychol Med2010401415019460188

- LamRWKennedySHMclntyreRSKhullarACognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: effects on psychosocial functioning and implications for treatmentCan J Psychiatry2014591264965425702365

- GondaXPompiliMSerafiniGCarvalhoAFRihmerZDomePThe role of cognitive dysfunction in the symptoms and remission from depressionAnn Gen Psychiatry2015142726396586

- KroenkeKSpitzerRLWilliamsJBThe PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measureJ Gen Intern Med200116960661311556941

- GuyWCGI: Clinical Global ImpressionsECDEU Assessment Manual for PsychopharmacologyRockville (MD)National Institute of Mental Health1976217222

- MontgomerySAAsbergMA new depression scale designed to be sensitive to changeBr J Psychiatry1979134382389444788

- SullivanJJEdgleyKDehouxEA survey of multiple sclerosis – part 1: perceived cognitive problems and compensatory strategy useCan J Rehabil19904299105

- National Multiple Sclerosis SocietyMultiple Sclerosis Quality of Life Inventory: A User’s ManualNew YorkNMSS1997

- HamiltonMThe assessment of anxiety states by ratingBr J Med Psychol1959321505513638508

- SheehanDVHarnett-SheehanKRajBAThe measurement of disabilityInt Clin Psychopharmacol199611Suppl 38995

- ReillyMCZbrozekASDukesEMThe validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrumentPharmacoeconomics19934535336510146874

- WareJJrKosinskiMKellerSDA 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validityMed Care19963432202338628042

- EuroQol GroupEuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of lifeHealth Policy199016319920810109801

- McGahueyCAGelenbergAJLaukesCAThe Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (ASEX): reliability and validityJ Sex Marital Ther2000261254010693114

- MoriskyDEGreenLWLevineDMConcurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherenceMed Care198624167743945130

- HawleyCJGaleTMSivakumaranTDefining remission by cut off score on the MADRS: selecting the optimal valueJ Affect Disord200272217718412200208

- ZimmermanMPosternakMAChelminskiIDerivation of a definition of remission on the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale corresponding to the definition of remission on the Hamilton rating scale for depressionJ Psychiatr Res200438657758215458853

- DunlopBWLiTKornsteinSGConcordance between clinician and patient ratings as predictors of response, remission, and recurrence in major depressive disorderJ Psychiatr Res20114519610320537348

- FrankEPrienRFJarrettRBConceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrenceArch Gen Psychiatry19914898518551929776

- GeddesJRCarneySMDaviesCRelapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic reviewLancet2003361935865366112606176

- SpijkerJBijlRVde GraafRNolenWADeterminants of poor 1-year outcome of DSM-III-R major depression in the general population: results of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS)Acta Psychiatr Scand2001103212213011167315

- KloiberSIsingMReppermundSOverweight and obesity affect treatment response in major depressionBiol Psychiatry200762432132617241618

- FavaMWiltseCWalkerDBrechtSChenAPerahiaDPredictors of relapse in a study of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorderJ Affect Disord2009113326327118625521

- RucciPFrankECalugiSIncidence and predictors of relapse during continuation treatment of major depression with SSRI, interpersonal psychotherapy, or their combinationDepress Anxiety2011281195596221898715

- NordenskjöldAvon KnorringLEngströmIPredictors of time to relapse/recurrence after electroconvulsive therapy in patients with major depressive disorder: a population-based cohort studyDepress Res Treat2011201147098522110913

- TrinhNHShyuIMcGrathPJExamining the role of race and ethnicity in relapse rates of major depressive disorderCompr Psychiatry201152215115521295221

- McGrathPJStewartJWPetkovaEPredictors of relapse during fluoxetine continuation or maintenance treatment of major depressionJ Clin Psychiatry200061751852410937611

- AngstmanKBShippeeNDMaclaughlinKLPatient self-assessment factors predictive of persistent depressive symptoms 6 months after enrollment in collaborative care managementDepress Anxiety201330214314823139162

- WangJLPattenSBCurrieSSareenJSchmitzNPredictors of 1-year outcomes of major depressive disorder among individuals with a lifetime diagnosis: a population-based studyPsychol Med201242232733421740627

- PapakostasGILarsenKTesting anxious depression as a predictor and moderator of symptom improvement in major depressive disorder during treatment with escitalopramEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2011261314715620859636

- KessingLVSubtypes of depressive episodes according to ICD-10: prediction of risk of relapse and suicidePsychopathology200336628529114646451

- JangSJungSPaeCKimberlyBPNelsonJCPatkarAAPredictors of relapse in patients with major depressive disorder in a 52-week, fixed dose, double blind, randomized trial of selegiline transdermal system (STS)J Affect Disord2013151385485924021959

- YangHChuziSSinicropi-YaoLType of residual symptom and risk of relapse during the continuation/maintenance phase treatment of major depressive disorder with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetineEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2010260214515019572158

- SheetsESDuncanLEBjornssonASCraigheadLWCraigheadWEPersonality pathology factors predict recurrent major depressive disorder in emerging adultsJ Clin Psychol201470653654523852879

- RiedelMMöllerHJObermeierMClinical predictors of response and remission in inpatients with depressive syndromesJ Affect Disord20111331–213714921555156

- GopinathSKatonWJRussoJELudmanEJClinical factors associated with relapse in primary care patients with chronic or recurrent depressionJ Affect Disord20071011–3576317156852

- ZimmermanMMcGlincheyJBPosternakMAFriedmanMBoerescuDAttiullahNRemission in depressed outpatients: more than just symptom resolution?J Psychiatr Res2008421079780117986389

- PaykelESRamanaRCooperZHayhurstHKerrJBarockaAResidual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depressionPsychol Med1995256117111808637947

- IshakWWGreenbergJMCohenRMPredicting relapse in major depressive disorder using patient-reported outcomes of depressive symptom severity, functioning, and quality of life in the Individual Burden of Illness Index for Depression (IBI-D)J Affect Disord20131511596523790554

- NovickDHongJMontgomeryWDueñasHGadoMHaroJMPredictors of remission in the treatment of major depressive disorder: real-world evidence from a 6-month prospective observational studyNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20151119720525653529

- SeidmanSEjaculatory dysfunction and depression: pharmacological and psychobiological interactionsInt J Impot Res200618Suppl 1S33S3816953246

- ClaytonAHEl HaddadSIluonakhamheJPPonce MartinezCSchuckAESexual dysfunction associated with major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatmentExpert Opin Drug Saf201413101361137425148932

- AshtonAKJamersonBDWeinsteinWLWagonerCAntidepressant-related adverse effects impacting treatment compliance: results of a patient surveyCurr Ther Res Clin Exp20056629610624672116

- WhismanMADepression and marital distress: findings from clinical and community studiesBeachSRMarital and Family Processes in DepressionWashingtonAmerican Psychological Association2001324

- WhismanMAMarital distress and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in a population-based national surveyJ Abnorm Psychol2007116363864317696721

- WhismanMAUebelackerLAProspective associations between marital discord and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and older adultsPsychol Aging200924118418919290750

- JuddLLPaulusMJSchettlerPJDoes incomplete recovery from first lifetime major depressive episode herald a chronic course of illness?Am J Psychiatry200015791501150410964869

- BortolatoBCarvalhoAFMcIntyreRSCognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a state-of-the-art clinical reviewCNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets201413101804181825470396

- WooYSRosenblatJDKakarRBahkWMMcIntyreRSCognitive deficits as a mediator of poor occupational function in remitted major depressive disorder patientsClin Psychopharmacol Neurosci201614111626792035

- KurianBTGreerTLTrivediMHStrategies to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of antidepressants: targeting residual symptomsExpert Rev Neurother20099797598419589048

- ZajeckaJKornsteinSGBlierPResidual symptoms in major depressive disorder: prevalence, effects, and managementJ Clin Psychiatry201374440741423656849

- KhanAKhanSRShanklesEBPolissarNLRelative sensitivity of the Montgomery-Ǻsberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Clinical Global Impressions Rating Scale in antidepressant clinical trialsInt Clin Psychopharmacol200217628128512409681

- JiangQAhmedSAn analysis of correlations among four outcome scales employed in clinical trials of patients with major depressive disorderAnn Gen Psychiatry20098419166588

- TrivediMHCorey-LislePKGuoZLennoxRDPikalovAKimERemission, response without remission, and nonresponse in major depressive disorder: impact on functioningInt Clin Psychopharmacol200924313313819318972

- KatzelnickDJDuffyFFChungHRegierDARaeDSTrivediMHDepression outcomes in psychiatric clinical practice: using a self-rated measure of depression severityPsychiatr Serv201162892993521807833

- GarrisonGMAngstmanKBO’ConnorSSWilliamsMDLineberryTWTime to remission for depression with collaborative care management (CCM) in primary careJ Am Board Fam Med2016291101726769872

- McMillanDGilbodySRichardsDDefining successful treatment outcome in depression using the PHQ-9: a comparison of methodsJ Affect Disord20101271–312212920569992

- ManeaLGilbodySMcMillanDOptimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysisCMAJ20121843E191E19622184363

- EllKKatonWLeePJDepressive symptom deterioration among predominantly Hispanic diabetes patients in safety net carePsychosomatics201253434735522458987

- HorneDKehlerSKaoukisGDepression before and after cardiac surgery: do all patients respond the same?J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg201314551400140623260432