Abstract

Interferon-α, currently used for the treatment of hepatitis C, is associated with a substantially elevated risk of depression. However, not everyone who takes this drug becomes depressed, so it is important to understand what particular factors may make some individuals more ‘at risk’ of developing depression than others. Currently there is no consensus as to why interferon-induced depression occurs and the range of putative risk factors is wide and diverse. The identification of risk factors prior to treatment may allow identification of patients who will become depressed on interferon, allowing the possibility of improved treatment support and rates of treatment adherence. Here, we consolidate and review the literature on risk factors, and we discuss the potential confounds within the research examined in order to better isolate the risk factors that may be important in the development of depression in these patients and which might help predict patients likely to become depressed on treatment. We suggest that interactions between psychobehavioral, genetic, and biological risk factors are of particular importance in the occurrence of depression in patients with hepatitis C taking interferon-α.

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of liver disease and death and affects ∼170 million people worldwide.Citation1 Recent epidemiological studies suggest more than 90% of transmission in developed countries occurs through the sharing of nonsterilized needles and syringes in the intravenous drug-using population, ‘unknown’ sources, and ‘other’ sources such as dialysis, hemophilia, sexual transmission, and tattoos or piercing.Citation2–Citation5 Rates through blood transfusion are decreasing dramatically in the developed world due to improved screening for viruses in blood donations since the early 1990s, although progress is somewhat slower in developing countries.Citation2 Progression from initial infection to liver cirrhosis and cancer can take 20–30 years;Citation6,Citation7 thus, complications from chronic HCV infection are, therefore, anticipated to continue to increase,Citation8 with rates of cirrhosis doubling, liver-related deaths tripling, and HCV becoming the leading reason for liver transplantation.Citation9

There is no vaccine for HCV; thus, the need for effective treatments for this infection is critical. Currently, the main Federal Drug Authority-approved treatment for HCV is the use of the proinflammatory cytokine interferon-α (IFN-α), a multifunctional pleiotropic protein with antiproliferative, antiviral, and immunoregulatory functions,Citation10 which is usually used in combination with broad-spectrum antiviral ribavirin. Unfortunately, this treatment is only effective in ∼40%–80% of patients, with efficacy varying dramatically between genotypes.Citation11,Citation12 Treatment is also expensive and has a well-documented profile of physical, behavioral, and psychiatric side effects, including flu-like symptoms, fatigue, insomnia, depressed mood, and irritability,Citation12–Citation16 all of which could impact upon compliance. Depression is a particularly common side effect that may occur in up to 60% of patients,Citation17,Citation18 and in some rare cases, it may be associated with deliberate self-harm or suicide attempts.Citation19,Citation20 The neuropsychiatric side effects of IFN-α therapy are among the commonest causes of treatment discontinuation,Citation21,Citation22 and risk factors such as baseline psychiatric symptoms and interpersonal problems can predict poor compliance.Citation23 Identification of the risk factors that lead to neuropsychiatric side effects and the associated low adherence rates may help identify patients at risk who may then benefit from additional psychological assessment and support.

Current treatment for IFN-α-induced depression involves the coadministration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which have been shown to improve treatment adherence in depressed patients.Citation24 However, variations in prescribing practice exist. Some clinicians wait for the depression to occur before prescribing these drugs, meaning up to a month may pass before a reduction in depressive symptoms occurs.Citation25 Other clinicians adopt a policy of prophylactically administering SSRIs to reduce the occurrence of depression and depressive symptomology, with dose modification where necessary,Citation26–Citation28 but this means a large number of patients who do not need an SSRI could be prescribed one. Where studies have identified ‘at-risk’ patients for prophylaxis of antidepressants and psychological support, these have both proven effective methods of reducing the occurrence of depression.Citation29–Citation31

In order to avoid depressive complications and associated treatment compliance risks, identification of risk factors for the subsequent development of depression could assist clinicians in deciding to coprescribe an antidepressant and psychological support at the start of antiviral treatment. Here, we provide an overview of data on HCV patients taking IFN-α in order to assess potential risk factors that affect the development of depression.

The main risk factors identified and investigated in this literature review can be divided into five main categories: biological, demographic, treatment related, genetic, and psychobehavioral. Here, we examine these categories and review evidence that these potential risk factors pose a sufficiently substantive risk of depression that pretreatment support should be considered.

Methods

A literature search was conducted in PubMed using the keywords ‘depression’, ‘interferon-α’, and ‘hepatitis C’. A total of 169 English, full-text, original research articles where rates of depression were assessed in the target population were then screened for their assessment of risk factors of depression. Those articles that used formal statistical analysis to assess possible risk factors were then broken down into five broad categories: biological, demographic, treatment related, genetic, and psychobehavioral. Once these categories were identified, further PubMed searches were conducted including category titles and subtitles as additional keywords. In total, 52 articles were assessed as part of the main review, and results from these articles are presented along with supporting evidence.

Review of risk factors

Biological risk factors

Biological mechanisms

Many humans or animals administered with a cytokine develop a behavioral syndrome and set of somatic effects termed ‘sickness behavior’; these behaviors result in an alteration of the motivational state of an organism so that it can preferentially respond to infections.Citation32–Citation34 In other words, the organism will have depressed functioning of mood, activity, and metabolism so that all of its energy is put into fighting illness. The observation that sickness behavior and depression share common featuresCitation35 (see ) has led many researchers to implicate raised levels of cytokines in the pathology of depression, giving rise to the cytokine theory of depression.

Table 1 Similarities between MDD and sickness behaviorCitation36–Citation39

The cytokine theory of depression suggests biological vulnerability in certain individuals that is linked, in part, to the immune system.Citation33 This could be exposed by a compound that stimulates the immune system (such as IFN-α), and increases in cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-10 are positively correlated with depressive symptoms.Citation40,Citation41 The enhanced cytokine response seen in depressed patients resonates with data that shows that people who become depressed during treatment are more likely to have a sustained antiviral response.Citation42,Citation43

Several potential biological mechanisms for this vulnerability to developing an IFN-α-induced depression have been examined.Citation17,Citation38,Citation42,Citation44–Citation47 Three main mechanisms that are supported by clinical data are introduced briefly before clinical data assessing their relationship with depression is discussed.

Serotonin

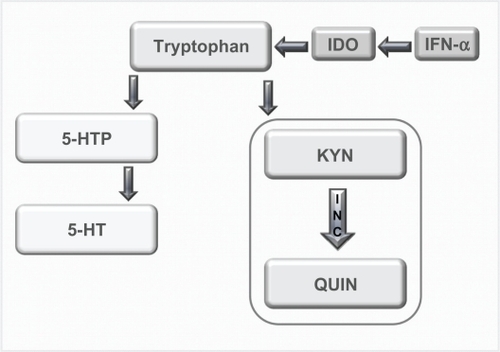

The neurotransmitter serotonin has long been believed to play a role in depression;Citation48,Citation49 however, more recent research has linked the observed decrease in serotonin with a cytokine-mediated pathway.Citation50,Citation51 When IFN-α is administered, it has been shown that there is an upregulation of the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) that metabolizes tryptophan, the precursor to serotonin.Citation34 Thus, when IDO is overstimulated, there is potentially a reduction in plasma tryptophan and serotonin in the brain (see ),Citation42,Citation45,Citation52 which may lead to depression.Citation51

Figure 1 Tyrptophan–Kynurenine pathway. Diagram showing the alteration of tryptophan metabolism by IFN-α. Tryptophan is normally converted in 5-hydroxy tryptophan (5-HTP) and serotonin (5-HT). However, this metabolism is switched to the KYN pathway by IDO, which is induced by immune stimuli such as IFN-α, and it is this pathway that produced the neurotoxin quinolinic acid (QUIN). Copyright © 2002, Elsevier. Adapted with permission from Konsman JP, Parnet P, Dantzer R. Cytokine-induced sickness behaviour: mechanisms and implications. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(3):154–159.

Serotonin as a risk factor

Clinical studies in HCV patients have provided mixed results regarding the involvement of serotonin in the IFN-α-induced depression; some studies support a correlation between lower tryptophan levels and scores on a depression scaleCitation53 and others do not find any correlation with tryptophanCitation54 or whole blood serotonin.Citation55 However, lower tryptophan has been correlated with other behavioral issues associated with depression such as increased irritability and aggression.Citation56 Reasons for differences in results could be in part explained by the low number of participants in the studies and also the issue of correlating the centrally driven disorder of depression with peripheral biomarkers. This issue has been addressed by two recent studies conducted by Raison et al.Citation57,Citation58 The first study found that when IFN-α was administered peripherally, there was an increase in the amount of kynurenine (KYN) and quinolinic acid (QUIN) centrally, which correlated with Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) scores. The second study found that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid were significant predictors of depressive symptoms.Citation57

Further support for the involvement of this system is the observation that depressive symptoms in this cohort are effectively ameliorated by the use of SSRIs,Citation25–Citation28,Citation59 implicating some role for serotonin in the relief of IFN-α-induced depression.

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

Interferons are acknowledged to activate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis,Citation60 which could in part be linked to the development of depression.Citation61–Citation63 Recent research has identified a pathway where stress can increase glucocorticoids and corticotrophin-releasing hormones, which act in tandem with an increase in cytokines to disrupt levels of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine.Citation50,Citation64,Citation65 Vulnerability in this pathway could mean a stress-related response to cytokines is in part responsible for IFN-induced depression.

HPA axis as a risk factor

There are mixed results for the involvement of peripheral biomarkers of HPA axis functioning in IFN-α-induced depression. One study found that IFN-α does not induce a change in plasma cortisol levels and cannot be correlated with depression scores.Citation55 Another found that although there was a significant increase in daily salivary cortisol following 8 weeks of treatment, this change was not significantly associated with depression scores.Citation66

However, a recent study that compared HCV patients who were and were not taking IFN-α found that treatment was associated with a relative flattening of the diurnal slope for both salivary cortisol and adrenocorticotrophin-releasing hormone production and that flattening of the cortisol slope was associated with depressive symptoms, particularly somatic depressive symptoms.Citation67 Issues leading to mixed results in these studies include the low number of participants and different measurements of cortisol (plasma cortisol and salivary cortisol). Another issue is the differing analyses employed by investigators with Raison et alCitation67 analyzing the daily cortisol slope, whereas Wichers et alCitation66 analyzed daily average cortisol levels.

Cytokine mechanisms

As IFN-α is a cytokine designed to affect immune system functioning, some researchers have chosen to look at baseline immune system functioning and the relative increase in cytokines induced by treatment to see if that had any effect on the subsequent development of depression.

One of the main questions regarding biological risk factors for development of an IFN-α-induced depression is how the immune system, which is a peripheral system, can exert effects on mood and behavior via the central nervous system (CNS). There are two main theories regarding this question; the first supposes that cytokines may enter the brain. There are a number of ways in which cytokines may enter the brain. The first is via circumventricular regions where the blood–brain barrier (BBB) is more permeableCitation68 such as the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis, with uptake mechanisms for cytokines such as IL-1 being demonstrated at the surface of the BBB.Citation69,Citation70 Active transport mechanisms for transportation into the brain are also being identified for cytokines, including IL-1Citation71 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).Citation72 Another hypothesis concerns the induction of adhesion molecules such as vascular endothelial growth factor-1 in the brain endothelium, which increases the potential for circulating T-lymphocytes to cross the BBB.Citation73

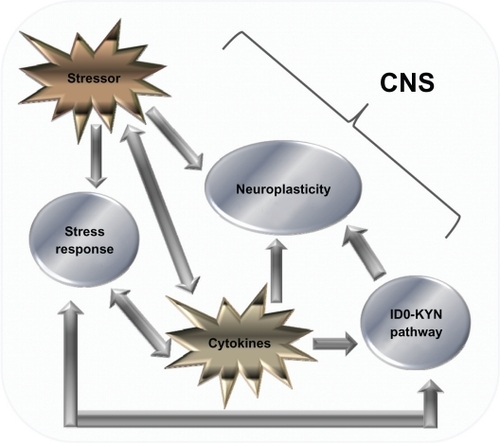

However, the second theory suggests that the immune system influences secondary factors that in turn interact with the CNS.Citation32 In the second scenario, there is a complex interplay between stressors, the IDO–KYN pathway (see ), and factors that influence neuroplasticity in the development of cytokine-induced depression (see ).Citation57,Citation74,Citation75

Figure 2 Cytokine-mediated pathways that influence the CNS. Diagram showing the various factors that influence the CNS. There is a complex relationship, the relationship with monoamines and the IDO–Kyn pathway, growth factors, and stress. Stressors and cytokines both increase the stress response, which is reflected by an increase in the amount of CRH, both in the CNS and peripherally, which in turn activates ACTH and cortisol (CORT) levels. CRH also has a bidirectional relationship with serotonin (5-HT) levels, and gamma aminobutyric acid acts as a mediator for this process. 5-HT levels are also influenced by the production of IDO, which favors the production of the neurotoxin KYN over 5-HT. The stressor system and IDO–KYN pathway both lead to a reduction in 5-HT. Cytokines also influence oxidative and apoptotic mechanisms, leading to a reduction in growth factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which in turn leads to impaired neuroplastic processes and decreased neurogenesis, as well as cytokines having an indirect effect on growth factor levels; stress has also been shown to have a direct effect. The culmination of these three pathways can lead to the development of major depression. Copyright © 2005, Elsevier. Adapted with permission from Hayley S, Poulter MO, Merali Z, Anisman H. The pathogenesis of clinical depression: stressor- and cytokine-induced alterations of neuroplasticity. Neuroscience. 2005;135(3):659–678.

Cytokines as a risk factor

The role of cytokines in IFN-α-induced depression is a complex one, with circulating cytokines, but not central cytokines, appearing to have a relationship with depression scores. It was found that a higher IL-6 response at weeks 2–4 was predictive of a higher MADRS score 4–6 months later.Citation40 Another study found that pretreatment levels of circulating IL-6 predicted the incidence of developing a major depressive disorder (MDD), and using regression analyses, the authors were able to predict the following month’s Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score using the previous month’s IL-6 levels.Citation41 Other studies have also found that a significantly increased baseline concentration of IL-6 can be a predictor for subsequent depression.Citation76 In addition to IL-6, other peripheral cytokines shown to correlate with an increase in depressive symptoms include the soluble IL-2 receptor and TNF-α,Citation66 with baseline levels of soluble IL-2 receptor and IL-10 being significantly increased in those patients who went on to develop depression.Citation76 Another study that examined the relative importance of cytokines in depressive symptomology found that TNF-α and not IL-6 was correlated with mood scores.Citation67

However, when central levels of cytokines were measured in CSF while IFN-α induced a significant increase in the cytokines IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), only CSF concentrations of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid predicted depressive symptoms.Citation57 These findings could mean that only peripheral cytokines can be correlated with depressive symptoms, possibly due to the influence of peripheral cytokines on the neurovegetative symptoms of depression.

Recent research is attempting to determine the specific neurobehavioral effect of cytokines by acknowledging the multidimensional nature of MDD as a disorder consisting of a number of specific subgroups of symptoms.Citation47 There is a possibility that cytokines may be involved in certain aspects of the depressive syndrome, such as sleep and appetite changes, rather than being the central neurobiological cause of depression.Citation35 There has been evidence that IL-6 may be linked in with poor sleep quality in patients taking IFN-α,Citation41 with poor sleep quality being identified as a predicting factor for the development of a subsequent depression.Citation41,Citation77

There is substantive support for the role of biological risk factors in the development of the IFN-α-induced depression. However, as results are not always conclusive and replicable, there is a possibility that this risk factor acts in conjuntion with other factors in the development of a depression.

Genetic risk factors

Biological mechanisms responsible for IFN-α-induced depression will inevitably be influenced by underlying genetic vulnerability. Several genetic polymorphisms have been associated with an increased risk of developing depression. One of the most reproducible findings in this area is the observation that people who have the short allele in the functional 5′ promoter of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) are significantly more likely to be depressed in response to a major life eventCitation78,Citation79 or in generalCitation80,Citation81 than those people with the long version of this allele. Other genes implicated in depression are involved in the functioning of glucocorticoids,Citation82 neuronal growth,Citation83 dystonia,Citation84 as well as the 5-HT1 A autoreceptor gene,Citation85 and the IL-1β geneCitation86 among others.Citation87,Citation88

These genes offer potential avenues for researchers looking to identify genetic risk factors to explore, and recent research conducted in HCV patients taking IFN has identified a number of genes that have been shown to correlate with depression (see ). The 5-HT transporter gene has been shown to have a role in the development of depression in addition to polymorphisms in the interferon receptor-A1 gene, the apoloprotein (APOE) 4 allele, the cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) and phospholipase A2 (PLA2) genes, and the IL-6 gene in patients taking IFN (see ). A number of researchers have shown that the short version of the 5-HTTLPR increases the risk of developing a depressive episode when undertaking IFN-α therapy.Citation92,Citation93

Table 2 Genetic risk factors

One recent study demonstrates the difficulty in generalizing results across different ethnic groups, with non-Hispanic Caucasians and Hispanic Caucasians both showing opposite risk polymorphisms of the 5-HTTLPR gene for depression,Citation93 meaning that results from different ethnic groups should be interpreted with caution. These studies are also limited by the different types of depression scales used such as the overall Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score,Citation91 BDI,Citation92–Citation94 Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS),Citation95 and BDI or SDS.Citation89

Some genes appear to be related to a specific subgroup of depressive symptoms rather than the depressive disorder as a whole. Both the interferon receptor-A1 and PLA2 genes were associated primarily with somatic and neurovegetative symptoms.Citation94,Citation95 The APOE 4 allele was shown to be more so associated with symptoms of anger and irritability,Citation90 with a recent study showing that a TNF-α polymorphism is also associated with labile anger and fatigue but not depression.Citation96 The 5-HTTLPR, IL-6, and 5-HT1A genes were associated with overall depression scores.Citation89,Citation91,Citation92 The 5-HTTLPR gene was also associated with sleep quality,Citation92 which is in itself a predictor of depression.Citation41,Citation77 Further work demonstrated that both the 5-HTTLPR and IL-6 genes are not associated with fatigue scores.Citation92

These studies show that different genes are possibly involved in different aspects of the depressive disorder. There is also the possibility that the future may yield some useful genetic markers so that clinicians may identify ‘at-risk’ individuals and also identify what subgroups of symptoms patients may experience.

Demographic and social risk factors

Several demographic factors potentially impact on the development of depression,Citation62 including age, gender, ethnicity, and education level. However, there is no consensus as to whether any of these factors impact on the development of depression in patients taking IFN-α (see ).

Table 3 Demographic risk factors

The problems with these studies are demonstrated by the work of Pierucci-Lagha et alCitation93 who found that there was a significant difference between ethnic groups at week 12 but that this difference was no longer significant at week 20. This could mean that the observed significant difference was an artifact rather than a true reflection of ethnic differences in depression, and thus all other results regarding ethnicity must be interpreted with caution.

The only social risk factor that appears to influence levels of depression is that of social support, with lower levels leading to a significantly higher risk of developing a depression.Citation24 Support for the involvement of this demographic factor also comes from research conducted in patients with malignant melanoma, where patients who employed effective coping strategies and had social support were less likely to become depressed.Citation105 However, more work needs to be conducted in this area before any concrete conclusions can be drawn.

Treatment-related risk factors

Higher doses of IFN-α are associated with more numerous side effects.Citation106,Citation107 However, it is not clear whether this observed dose effect also holds for the development of depression (see ). In general, rates of depression in patients taking IFN-α for HCV vary from 0%Citation109,Citation118 to up to 50%.Citation21,Citation62,Citation97,Citation99–Citation101,Citation104,Citation108,Citation113,Citation116 Oncology patients taking up to five times the dose of IFN-α than those patients infected with HCV are prescribed have similar rates of depression from 5%Citation119 up to 50%.Citation120 Given that the doses of IFN-α given to the two populations are very different, there does not appear to be a convincing difference regarding the impact of dose on development of depression. However, a potential confounding factor is the retrospective design of most of these studies. This design can yield lower rates of depression than prospective depression-specific design, used by many contemporary researcher-led studies,Citation62 perhaps also explaining the lower rates of depression seen in some of the studies in .Citation107

Table 4 Studies reviewed to assess whether treatment-related risk factors can be associated with development of depression in patients prescribed IFN-α

Other treatment-related factors such as coprescription of ribavirin and length of treatment do not seem to yield a general consensus on the impact of treatment-related risk factors on depression. This suggests that while treatment factors impact on the ‘sickness’ aspect of sickness behavior, that is, those somatic complaints that follow an infection or illness (see ), there is little evidence suggesting that they impact hugely on the behavioral aspects of sickness behavior, one of which is depression.

Psychobehavioral risk factors

Risk factors implicating both psychological and behavioral vulnerabilities as being predictors of subsequent depression have been arguably the most researched in this field as simple reasoning would suggest that if a drug induces psychobehavioral side effects, a pre-existing vulnerability to developing a psychiatric disorder (be that history, current diagnosis, behavioral problems, or higher than normal rating on a psychiatric scale) should lead such patients to be more ‘at risk’ than others. Following an early observation that higher pretreatment scores on a depressive rating scale led to cancer patients having a higher risk of becoming depressed,Citation121 several studies on HCV patients have explored this observation in more detail, with an emerging consensus that this risk factor results in patients being significantly more likely to develop depression when taking IFN-α (see ). It could, however, also be argued that this ‘risk factor’ has the most support simply because it has been the most investigated. This risk factor goes hand in hand with findings which suggest that people with a past history of psychiatric illness, in particular MDD, are more vulnerable to becoming depressed on treatment.Citation62,Citation97 The research summarized in suggests that some kind of ‘subsyndromal’ depression could leave people more susceptible to developing an IFN-α-induced depression.

Table 5 Psychiatric risk factors

It has been shown that those people who become depressed on treatment are more likely to have an increased baseline score on a depression scale (see ). Raison et alCitation127 propose that all people prescribed IFN-α develop a side effect profile, comprised of neurovegetative symptoms (those somatic aspects of sickness behavior) or depressive-specific symptoms (those symptoms specific to the behavioral parts of sickness behavior). Both of these side effect profiles are measured by depression rating scales. Thus, if a person scores highly at baseline on one of these scales, it would stand to reason that these scores would remain throughout the course of the treatment and that some additional treatment-related factors would also come into play. The additive effect would mean that this subset of patients would be more at risk of being diagnosed with a depressive disorder due to elevated scores on a depression rating scale. Should this be the case, then all patients would experience an increase in scores on a depression rating scale relative to time, which is something that much of the literature seems to support.Citation23,Citation25,Citation104,Citation108,Citation111,Citation113,Citation114,Citation125,Citation128–Citation134 In fact, some researchers have pinpointed a relative increase in somatic components of depressive rating scales as being primarily responsible for the increase in scores seen in many patients.Citation46 However, many recent studies have become aware of the potential confounds associated with using only depression rating scales; the range cannot be deleted and so diagnose MDD using DSM-IV-TR criteria. In order to meet criteria for diagnosis of MDD, patients are required to show depressed mood for most of the days, nearly every day, and/or demonstrate a direct loss in interest in activities every day for 2 weeks. Neither of these factors are somatic in nature, although it could be said that they may result from a primarily somatic complaint.

Psychiatric morbidity at baseline is perhaps the most intriguing of all research in this area. Evidence, however, is varied with some studies finding no difference in development of depression in patients taking IFN-α, regardless of psychiatric history, and some indicating that patients are more likely to develop depression should they exhibit psychiatric vulnerability (see ). This in part could be related to the fact that many of the studies that investigate a predefined ‘at-risk’ population such as those who have pre-existing psychiatric disorder are often coprescribed additional support at baseline with SSRIs and therapy.Citation29–Citation31

Another important issue with this population is whether researchers are investigating the incidence of total depression or ‘new’ depression only. Hauser et alCitation99 reported an incidence of 6% of ‘new’ depression in the psychiatric group, which was not significant when compared against the incidence of ‘new’ depression in the other groups examined. However, if people depressed prior to treatment were included, then the total incidence of depression in this group was 44%, a much higher rate than in other groups. Some studies that have found evidence for a past psychiatric history impacting on IFN-α-induced depression include people who were diagnosed as being depressed prior to the start of treatment (see ). This begs the question of which approach is better. If examining a ‘psychiatric group’, then a substantial proportion of this group may have depression, and removing this group from subsequent analyses will impact upon the level of depression observed. At the same time, however, these studies are supposedly examining IFN-α-induced depression, and if a person is depressed when commencing treatment, the depression observed while on treatment is not an IFN-α-induced phenomenon and should not be included.

The approach adopted by Hauser et alCitation99 is perhaps the most sensible, given this dilemma. They report their results in terms of ‘new depression’ but also mention that those depressed prior to treatment were more likely to develop moderate or severe depression compared to patients in other groups, thus providing evidence that IFN-α may increase depressive symptoms relative to the baseline that people begin treatment at. Thus, people with a lower ‘baseline depression’ will have an increase in depressive symptoms, but this is not always necessarily enough of an increase to mean a diagnosis of depression. However, those people with higher depression scores when commencing treatment will have the same kind of increase in depressive symptoms leading, in their case, to a diagnosis of depression.

Another risk factor that has increasing support is personality, with those individuals who have low self-directednessCitation122 and high neuroticismCitation92,Citation104 being more likely to become depressed on treatment. The likelihood is that these personality factors interact with other psychobehavioral risk factors; however, more research needs to be conducted in order to determine this.

A behavioral risk factor that is gaining increasing interest from researchers is the impact of sleep disorders on the subsequent development of depression. Studies have shown that those patients who exhibit higher scores on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index at baseline are more likely to develop MDD in a shorter time span,Citation77 with sleep disturbance on treatment being a predictive factor for subsequent depression scale scoresCitation41 and suicidal ideation.Citation102 However, a recent literature review on sleep disturbance in HCV states that the presence of insomnia in this cohort is influenced by underlying psychiatric comorbidity such as depression.Citation122 This could mean that sleep disturbance interacts with other risk factors in determining the possible risk of developing depression in individuals. This idea is supported by Lotrich et alCitation92 who found that when assessed alone, baseline sleep quality and BDI could predict depression; however, when Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and BDI scores were combined with 5-HTTLPR genotype, the effect of sleep and depression scale scores were diminished and only genotype had a significant impact on the development of depression.

The area of psychobehavioral risk factors impacting on subsequent development of IFN-α-induced depression is perhaps the most convincing in terms of evidence gathered and rationale supplied by researchers. This risk factor is inevitably influenced by genetic and/or biological vulnerabilities.

Limitations

Limitations of cited studies

Many of the studies examined are retrospective and have only identified ‘risk factors’ following patients’ completion of treatment. It could, therefore, be argued that it is easy to retrospectively identify a risk factor using statistics to compare ‘depressed’ and ‘nondepressed’ groups. In fact, a prospective depression-specific design rather than the retrospective general design often employed in clinical trials generally yields much higher rates of depression.Citation135 Despite this, a risk factor might only be identified using a prospective depression-specific design, and following identification of that risk factor, other studies could have the effect of that particular risk factor on the development of depression as their primary hypothesis. This has certainly been the case with many studies on psychiatric side effects, and this area of research has much stronger empirical evidence supporting it than others (eg, demographic risk factors, which when examined in a study, appears to be an afterthought examined only retrospectively). Paradoxically, many studies have focused from the outset on the side effect of depression and will often find higher rates of depression, as they are ‘on the look out’ for this specific side effect. Studies of general side effects rather than the specific side effect of depression have found lower rates of depression. It may be the same with other risk factors. Should researchers and clinicians be more aware that certain risk factors could lead to an increased likelihood of depression being developed, depression in these individuals may be diagnosed more quickly. Many of these studies employ scales to examine depressive symptoms, and these scales are often high in somatic items, which because of IFN-α being a drug that induces a ‘sickness behavior’, many patients taking this drug will score highly on these items simply because they are sick, rather than being depressed per se.Citation46 It will be important in future studies to determine the subscale loads of those items that are somatic or affective.

When assessing the role of the various biological and genetic risk factors identified in this review, there are some key issues that limit the interpretation of results. Many of the biological risk factors identified were not readily identifiable at baseline and instead are correlated with depressive symptoms after the induction of therapy. Another issue is the problem of correlating mood scores with a biomarker; high scores on a depression scale are not neccesarily representative of a depressive disorder and could instead be linked in to higher somatic symptoms. Some studies have shown that their biomarker of interest is preferentially correlated with somatic symptoms,Citation67,Citation94,Citation95 and future work should determine which cluster of symptoms each biomarker is associated with. The majority of studies examined in this review chose to conduct correlational and regression analysis, with no studies comparing between groups who did and did not develop a depression. In future, it would be interesting to conduct analyses that include all comparisons in order to gain a full appreciation of the role of biomarkers in IFN-α-induced depression.

Moreover, in issues relating to experimental design, there is the simple, yet often ignored issue that many patients who have HCV are more depressed than a healthy population; in fact, rates of depression in HCV patients can be as high as 40%.Citation136 Yates and GleasonCitation137 found that in a study of 78 patients who were HCV positive, the main reasons for being referred for psychiatric consultation were showing psychiatric symptoms, consultations either prior to listing for liver transplantation and/or therapy with IFN-α, and that the lowest number of patients that were referred for treatment in this group were those patients receiving IFN-α who had developed depressive symptoms. Furthermore, populations acquiring HCV tend to be from backgrounds that can lead them to have a higher level of depression regardless of treatment with IFN-α.Citation138 This evidence demonstrates that the HCV population is a vulnerable group generally and that focusing on only treatment-associated problems may lead clinicians and researchers alike to underestimate those problems that are associated with HCV itself.

Limitations of review

The results reported in this review are also limited by a number of factors. The first one being that only accessible articles were included within the review, and those articles that could not be accessed due to language constraints or inability to access full-text content were not included, which could have an impact on the risk factors identified and discussion of these factors.

In addition, there are some risk factors shown to impact on rates of depression that do not necessarily fit within the pre-defined categories and are not readily identifiable at baseline. Robaeys et alCitation116 found that vegetative-depressive symptoms at week 4 of treatment were predictive of a subsequent diagnosis of MDD; however, there were no differences between groups at baseline. Likewise, decreased motor speed was associated with increased symptoms of depression and fatigue.Citation134

There are also some biological factors that influence IFN-α-induced depression that were not explored in the literature review due to the paucity of literature in that area. One such factor is brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which has been shown to correlate with BDI scores.Citation139

Other studies have examined risk factors in different patient populations. IFN-α is also used as treatment for certain cancers such as malignant melanoma,Citation52,Citation140 and there are studies within this population that support various risk factors that have been examined within this review such as HPA axis biomarkers,Citation140 lower levels of tryptophan,Citation52 higher pretreatment depression scores,Citation141 low social support, sleep disturbance, pessimistic thoughts, and sadness.Citation105

Only those studies that looked at risk factors for depression were examined. In future, it will be important to determine what protective factors prevent people from developing a depression. There is some evidence presented that social support may be a protective factor against the development of depression,Citation24 and further research could determine what other protective factors are important.

When interpreting the results from this review, clinicians also need to be aware of the individual nature of depression and the varying risk factors that will cause each individual to become depressed. Even though this review has found strong evidence for certain risk factors, this does not mean to say that any person who experiences these factors will become depressed; it means that they are at a higher risk of developing depression than others who do not have these risk factors and thus extra assessment and support should be administered prior to commencement of treatment in those individuals who have been ascertained to be at risk of developing depression.

Finally, all results should be interpreted with caution due to the differing methodologies and analyses undertaken in all the studies within this review. While care has been taken to narrow the scope of the review by concentrating only on HCV patients, there are still differences between all the studies included here. These include the number of patients in each study, the type of statistical analysis run, the types of depression analysis undertaken (clinician rated and self-rated, depression scale or clinical diagnosis), and how each researcher defined depression (clinical diagnosis or cutoff point on depression scale). These should be recognized to be limiting factors in interpreting the results of this review.

Conclusions

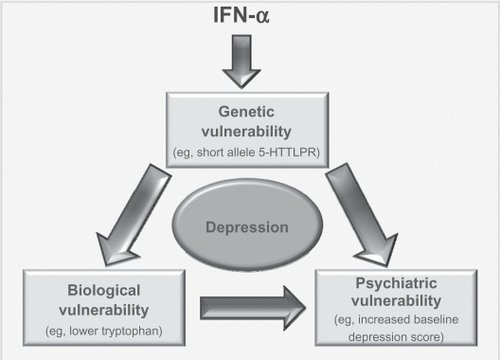

The current climate of psychiatric research is one where there is an acknowledgment of the multidisciplinary factors that play into any psychiatric disorder. Current research is, therefore, focused on finding interactions between genetic, biological, demographic, and psychobehavioral factors that lead some people to be more vulnerable to developing psychiatric disorders than others. It would be very difficult to identify a single risk factor that would lead people to be more susceptible to becoming depressed on IFN-α than others. However, the most convincing research conducted in this area is that which has examined biological,Citation41,Citation57,Citation58 genetic,Citation89,Citation91–Citation93 and psychobehavioralCitation41,Citation62,Citation77,Citation92,Citation97 risk factors, and it is no surprise that these three risk factors interact with one another (for an example of the way these three risk factors could interact to produce depression, see ).

Figure 3 Interaction of risk factors. Model by which various risk factors could interact to possibly produce depression in those patients taking IFN-α. It is possible that administration of IFN-α could lead to some underlying genetic vulnerability (eg, the short allele in 5-HTLLPR) impacting upon levels of a chemical such as tryptophan. This vulnerability, along with the biological response it could induce, would also interact with a psychiatric vulnerability. As these people have the genetic vulnerability, they are more likely to be depressed at baseline and/or have had a history of psychiatric disorders. All this would lead the person to be vulnerable to developing depression following administration of IFN.

Clinicians and researchers should be wary when trying to pinpoint one risk factor to concentrate on when attempting to identify ‘at-risk’ individuals. Instead, there should be an awareness of the complex interplay of biological, psychobehavioral, and genetic factors that lead some people to develop depression while taking IFN-α (see ). Two recent studies have examined interactions between genetic and psychobehavioral risk factors,Citation92,Citation93 demonstrating the need for more translational research in determining the relationship between different risk factors. Only when more research of this nature has been conducted, more concrete conclusions regarding the interaction and importance of individual risk factors can be determined.

Clinicians should attempt to assess people fully at baseline using as many tools available to them, such as depression rating scales, sleep disturbance questionnaires, psychiatric histories, and biological analysis of tryptophan and/or stress hormones. In future, it may also be possible to use genetic tools to identify individuals susceptible to development of IFN-α-induced depression. HCV-infected patients taking IFN-α are undoubtedly a vulnerable population. Effective pretreatment screening for baseline risk factors combined with more effective support during treatment will enable health care workers to better identify patients at risk and provide the additional treatment required should depression develop, thus improving adherence rates and improving clearance of HCV infection.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all staff in the Hepatology Centre, in particular, Barbara Hynes, Clodagh Quinn, and Helena Irish, as well as the Psychological Services Department at St James’s Hospital, for their help in allowing us to better understand the patients’ perspective of taking IFN-α. Supported by the Health Research Board (Ireland).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ShepardCWFinelliLAlterMJGlobal epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infectionLancet Infect Dis20055955856716122679

- PoynardTYuenMFRatziuVLaiCLViral hepatitis CLancet200336294012095210014697814

- EstebanJISauledaSQuerJThe changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in EuropeJ Hepatol200848114816218022726

- RantalaMvan de LaarMJSurveillance and epidemiology of hepatitis B and C in Europe – a reviewEuro Surveill20081321 Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=18880. Accessed 2010 Sep 18.

- AlterMJEpidemiology of hepatitis C virus infectionWorld J Gastroenterol200713172436244117552026

- AlazawiWCunninghamMDeardenJFosterGRSystematic review: outcome of compensated cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C infectionAliment Pharmacol Ther201032334435520497143

- LeoneNRizzettoMNatural history of hepatitis C virus infection: from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis, to hepatocellular carcinomaMinerva Gastroenterol Dietol2005511314615756144

- PatelKMuirAJMcHutchisonJGDiagnosis and treatment of chronic hepatitis C infectionBMJ200633275481013101716644828

- DavisGLAlbrightJECookSFRosenbergDMProjecting future complications of chronic hepatitis C in the United StatesLiver Transpl20039433133812682882

- StarkGRKerrIMWilliamsBRSilvermanRHSchreiberRDHow cells respond to interferonsAnnu Rev Biochem1998672272649759489

- BaconBRManaging hepatitis CAm J Manag Care200410Suppl 2S30S4015084065

- DavisGLEsteban-MurRRustgiVInterferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy GroupN Engl J Med199833921149314999819447

- CotlerSJWartelleCFLarsonAMGretchDRJensenDMCarithersRLJrPretreatment symptoms and dosing regimen predict side-effects of interferon therapy for hepatitis CJ Viral Hepat20007321121710849263

- FosterGMathurinPHepatitis C virus therapy to dateAntivir Ther200813Suppl 1S3S8

- KowdleyKVHematologic side effects of interferon and ribavirin therapyJ Clin Gastroenterol200539Suppl 1S3S815597025

- OngJPYounossiZMManaging the hematologic side effects of antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C: anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopeniaCleve Clin J Med200471Suppl 3S17S2115468613

- CapuronLMillerAHCytokines and psychopathology: lessons from interferon-alphaBiol Psychiatry2004561181982415576057

- DieperinkEWillenbringMHoSBNeuropsychiatric symptoms associated with hepatitis C and interferon alpha: a reviewAm J Psychiatry2000157686787610831463

- FukunishiKTanakaHMaruyamaJBurns in a suicide attempt related to psychiatric side effects of interferonBurns19982465815839776102

- JanssenHLBrouwerJTvan der MastRCSchalmSWSuicide associated with alfa-interferon therapy for chronic viral hepatitisJ Hepatol19942122412437989716

- McHutchisonJGGordonSCSchiffERInterferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy GroupN Engl J Med199833921148514929819446

- BernsteinDKleinmanLBarkerCMRevickiDAGreenJRelationship of health-related quality of life to treatment adherence and sustained response in chronic hepatitis C patientsHepatology200235370470811870387

- KrausMRSchaferACsefHFallerHMorkHScheurlenMCompliance with therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: associations with psychiatric symptoms, interpersonal problems, and mode of acquisitionDig Dis Sci200146102060206511680576

- EvonDMRamcharranDBelleSHTerraultNAFontanaRJFriedMWProspective analysis of depression during peginterferon and ribavirin therapy of chronic hepatitis C: results of the Virahep-C studyAm J Gastroenterol2009104122949295819789525

- KrausMRSchaferASchottkerKTherapy of interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C with citalopram: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyGut200857453153618079286

- GleasonOCFucciJCYatesWRPhilipsenMAPreventing relapse of major depression during interferon-alpha therapy for hepatitis C – a pilot studyDig Dis Sci200752102557256317436092

- RaisonCLWoolwineBJDemetrashviliMFParoxetine for prevention of depressive symptoms induced by interferon-alpha and ribavirin for hepatitis CAliment Pharmacol Ther200725101163117417451562

- MorascoBJRifaiMALoftisJMIndestDWMolesJKHauserPA randomized trial of paroxetine to prevent interferon-alpha-induced depression in patients with hepatitis CJ Affect Disord20071031–3839017292481

- SchaeferMSchwaigerMGarkischASPrevention of interferon-alpha associated depression in psychiatric risk patients with chronic hepatitis CJ Hepatol200542679379815885349

- SchaeferMSchmidtFFolwacznyCAdherence and mental side effects during hepatitis C treatment with interferon alfa and ribavirin in psychiatric risk groupsHepatology200337244345112540795

- ParianteCMOrruMGBaitaAFarciMGCarpinielloBTreatment with interferon-alpha in patients with chronic hepatitis and mood or anxiety disordersLancet1999354917313113210408496

- DantzerRBlutheRMGheusiGMolecular basis of sickness behaviorAnn N Y Acad Sci19988561321389917873

- DantzerRO’ConnorJCFreundGGJohnsonRWKelleyKWFrom inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brainNat Rev Neurosci200891465618073775

- KonsmanJPParnetPDantzerRCytokine-induced sickness behaviour: mechanisms and implicationsTrends Neurosci200225315415911852148

- DunnAJSwiergielAHde BeaurepaireRCytokines as mediators of depression: what can we learn from animal studies?Neurosci Biobehav Rev2005294–589190915885777

- HartBLBiological basis of the behavior of sick animalsNeurosci Biobehav Rev19881221231373050629

- CharltonBGThe malaise theory of depression: major depressive disorder is sickness behavior and antidepressants are analgesicMed Hypotheses200054112613010790737

- LotrichFEMajor depression during interferon-alpha treatment: vulnerability and preventionDialogues Clin Neurosci200911441742520135899

- SchiepersOJWichersMCMaesMCytokines and major depressionProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200529220121715694227

- BonaccorsoSPuzellaAMarinoVImmunotherapy with interferon-alpha in patients affected by chronic hepatitis C induces an intercorrelated stimulation of the cytokine network and an increase in depressive and anxiety symptomsPsychiatry Res20011051–2455511740974

- PratherAARabinovitzMPollockBGLotrichFECytokine-induced depression during IFN-alpha treatment: the role of IL-6 and sleep qualityBrain Behav Immun20092381109111619615438

- LoftisJMHauserPThe phenomenology and treatment of interferon-induced depressionJ Affect Disord200482217519015488246

- MaddockCLandauSBarryKPsychopathological symptoms during interferon-alpha and ribavirin treatment: effects on virologic responseMol Psychiatry200510433233315655564

- CapuronLDantzerRMillerAHNeuro-immune interactions in psychopathology with the example of interferon-alpha-induced depressionJ Soc Biol2003197215115612910630

- SchaeferMEngelbrechtMAGutOInterferon alpha (IFNalpha) and psychiatric syndromes: a reviewProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200226473174612188106

- TraskPCEsperPRibaMRedmanBPsychiatric side effects of interferon therapy: prevalence, proposed mechanisms, and future directionsJ Clin Oncol200018112316232610829053

- LoftisJMHuckansMMorascoBJNeuroimmune mechanisms of cytokine-induced depression: current theories and novel treatment strategiesNeurobiol Dis201037351953319944762

- ElhwuegiASCentral monoamines and their role in major depressionProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200428343545115093950

- OwensMJNemeroffCBRole of serotonin in the pathophysiology of depression: focus on the serotonin transporterClin Chem19944022882957508830

- MaleticVRobinsonMOakesTIyengarSBallSGRussellJNeurobiology of depression: an integrated view of key findingsInt J Clin Pract200761122030204017944926

- MiuraHOzakiNSawadaMIsobeKOhtaTNagatsuTA link between stress and depression: shifts in the balance between the kynure-nine and serotonin pathways of tryptophan metabolism and the etiology and pathophysiology of depressionStress200811319820918465467

- CapuronLNeurauterGMusselmanDLInterferon-alpha-induced changes in tryptophan metabolism. relationship to depression and paroxetine treatmentBiol Psychiatry200354990691414573318

- BonaccorsoSMarinoVPuzellaAIncreased depressive ratings in patients with hepatitis C receiving interferon-alpha-based immunotherapy are related to interferon-alpha-induced changes in the serotonergic systemJ Clin Psychopharmacol2002221869011799348

- MaesMBonaccorsoSMarinoVTreatment with interferon-alpha (IFN alpha) of hepatitis C patients induces lower serum dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity, which is related to IFN alpha-induced depressive and anxiety symptoms and immune activationMol Psychiatry20016447548011443537

- FontanaRJKronfolZLindsayKLChanges in mood states and biomarkers during peginterferon and ribavirin treatment of chronic hepatitis CAm J Gastroenterol2008103112766277518721241

- RussoSKemaIPHaagsmaEBIrritability rather than depression during interferon treatment is linked to increased tryptophan catabolismPsychosom Med200567577377716204437

- RaisonCLBorisovASMajerMActivation of central nervous system inflammatory pathways by interferon-alpha: relationship to monoamines and depressionBiol Psychiatry200965429630318801471

- RaisonCLDantzerRKelleyKWCSF concentrations of brain tryptophan and kynurenines during immune stimulation with IFN-alpha: relationship to CNS immune responses and depressionMol Psychiatry201015439340319918244

- KrausMRSchaferAFallerHCsefHScheurlenMParoxetine for the treatment of interferon-alpha-induced depression in chronic hepatitis CAliment Pharmacol Ther20021661091109912030950

- DafnyNYangPBInterferon and the central nervous systemEur J Pharmacol20055231–311516226745

- AsnisGMde La GarzaR2ndInterferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: a review of its prevalence, risk factors, biology, and treatment approachesJ Clin Gastroenterol200640432233516633105

- RaisonCLBorisovASBroadwellSDDepression during pegylated interferon-alpha plus ribavirin therapy: prevalence and predictionJ Clin Psychiatry2005661414815669887

- LeonardBEThe HPA and immune axes in stress: the involvement of the serotonergic systemEur Psychiatry200520Suppl 1S302S30616459240

- AnismanHCascading effects of stressors and inflammatory immune system activation: implications for major depressive disorderJ Psychiatry Neurosci200934142019125209

- RaisonCLCapuronLMillerAHCytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depressionTrends Immunol2006271243116316783

- WichersMCKenisGKoekGHRobaeysGNicolsonNAMaesMInterferon-alpha-induced depressive symptoms are related to changes in the cytokine network but not to cortisolJ Psychosom Res200762220721417270579

- RaisonCLBorisovASWoolwineBJMassungBVogtGMillerAHInterferon-alpha effects on diurnal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: relationship with proinflammatory cytokines and behaviorMol Psychiatry201015553554718521089

- MaierSFWatkinsLRCytokines for psychologists: implications of bidirectional immune-to-brain communication for understanding behavior, mood, and cognitionPsychol Rev19981051831079450372

- BegleyDJThe interaction of some centrally active drugs with the blood-brain barrier and circumventricular organsProg Brain Res1992911631691410401

- ErmischABrustPKretzschmarRRuhleHJPeptides and blood-brain barrier transportPhysiol Rev19937334895278392735

- DunnAJEndotoxin-induced activation of cerebral catecholamine and serotonin metabolism: comparison with interleukin-1J Pharmacol Exp Ther199226139649691602402

- GutierrezEGBanksWAKastinAJMurine tumor necrosis factor alpha is transported from blood to brain in the mouseJ Neuroimmunol19934721691768370768

- BrownMDWickTMEckmanJRActivation of vascular endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression by sickle blood cellsPediatr Pathol Mol Med2001201477212673844

- AnismanHMeraliZPoulterMOHayleySCytokines as a precipitant of depressive illness: animal and human studiesCurr Pharm Des200511896397215777247

- HayleySPoulterMOMeraliZAnismanHThe pathogenesis of clinical depression: stressor- and cytokine-induced alterations of neuroplasticityNeuroscience2005135365967816154288

- WichersMCKenisGLeueCKoekGRobaeysGMaesMBaseline immune activation as a risk factor for the onset of depression during interferon-alpha treatmentBiol Psychiatry2006601777916487941

- FranzenPLBuysseDJRabinovitzMPollockBGLotrichFEPoor sleep quality predicts onset of either major depression or subsyndromal depression with irritability during interferon-alpha treatmentPsychiatry Res20101771–224024520381876

- CaspiASugdenKMoffittTEInfluence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT geneScience2003301563138638912869766

- BrownGWHarrisTODepression and the serotonin transporter 5-HTTLPR polymorphism: a review and a hypothesis concerning gene-environment interactionJ Affect Disord2008111111218534686

- HoefgenBSchulzeTGOhlraunSThe power of sample size and homogenous sampling: association between the 5-HTTLPR serotonin transporter polymorphism and major depressive disorderBiol Psychiatry200557324725115691525

- PezawasLMeyer-LindenbergADrabantEM5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depressionNat Neurosci20058682883415880108

- BinderEBSalyakinaDLichtnerPPolymorphisms in FKBP5 are associated with increased recurrence of depressive episodes and rapid response to antidepressant treatmentNat Genet200436121319132515565110

- TadokoroKHashimotoRTatsumiMKosugaAKamijimaKKunugiHThe gem interacting protein (GMIP) gene is associated with major depressive disorderNeurogenetics20056312713316086184

- HeimanGAOttmanRSaunders-PullmanRJOzeliusLJRischNJBressmanSBIncreased risk for recurrent major depression in DYT1 dystonia mutation carriersNeurology200463463163715326234

- LemondeSTureckiGBakishDImpaired repression at a 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor gene polymorphism associated with major depression and suicideJ Neurosci200323258788879914507979

- RosaAPeraltaVPapiolSInterleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) gene and increased risk for the depressive symptom-dimension in schizophrenia spectrum disordersAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2004124B1101414681906

- LevinsonDFThe genetics of depression: a reviewBiol Psychiatry2006602849216300747

- ShynSIHamiltonSPThe genetics of major depression: moving beyond the monoamine hypothesisPsychiatr Clin North Am201033112514020159343

- BullSJHuezo-DiazPBinderEBFunctional polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 and serotonin transporter genes, and depression and fatigue induced by interferon-alpha and ribavirin treatmentMol Psychiatry200914121095110418458677

- GocheePAPowellEEPurdieDMAssociation between apolipoprotein E epsilon4 and neuropsychiatric symptoms during interferon alpha treatment for chronic hepatitis CPsychosomatics2004451495714709760

- KrausMRAl-TaieOSchaferAPfersdorffMLeschKPScheurlenMSerotonin-1A receptor gene HTR1A variation predicts interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis CGastroenterology200713241279128617408646

- LotrichFEFerrellRERabinovitzMPollockBGRisk for depression during interferon-alpha treatment is affected by the serotonin transporter polymorphismBiol Psychiatry200965434434818801474

- Pierucci-LaghaACovaultJBonkovskyHLA functional serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and depressive effects associated with interferon-alpha treatmentPsychosomatics201051213714820332289

- SuKPHuangSYPengCYPhospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase 2 genes influence the risk of interferon-alpha-induced depression by regulating polyunsaturated fatty acids levelsBiol Psychiatry201067655055720034614

- YoshidaKAlagbeOWangXPromoter polymorphisms of the interferon-alpha receptor gene and development of Interferon-induced depressive symptoms in patients with chronic hepatitis C: preliminary findingsNeuropsychobiology2005522556115990456

- LotrichFEFerrellRERabinovitzMPollockBGLabile anger during interferon alfa treatment is associated with a polymorphism in tumor necrosis factor alphaClin Neuropharmacol201033419119720661026

- CasteraLConstantAHenryCImpact on adherence and sustained virological response of psychiatric side effects during peginterferon and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis CAliment Pharmacol Ther20062481223123017014581

- HorikawaNYamazakiTIzumiNUchiharaMIncidence and clinical course of major depression in patients with chronic hepatitis type C undergoing interferon-alpha therapy: a prospective studyGen Hosp Psychiatry2003251343812583926

- HauserPKhoslaJAuroraHA prospective study of the incidence and open-label treatment of interferon-induced major depressive disorder in patients with hepatitis CMol Psychiatry20027994294712399946

- MiyaokaHOtsuboTKamijimaKIshiiMOnukiMMitamuraKDepression from interferon therapy in patients with hepatitis CAm J Psychiatry19991567112010401474

- Martin-SantosRDiez-QuevedoCCastellviPDe novo depression and anxiety disorders and influence on adherence during peginterferon-alpha-2a and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis CAliment Pharmacol Ther200827325726517988237

- GohierBGoebJLRannou-DubasKFouchardICalesPGarreJBHepatitis C, alpha interferon, anxiety and depression disorders: a prospective study of 71 patientsWorld J Biol Psychiatry20034311511812872204

- BonaccorsoSMarinoVBiondiMGrimaldiFIppolitiFMaesMDepression induced by treatment with interferon-alpha in patients affected by hepatitis C virusJ Affect Disord200272323724112450640

- LotrichFERabinovitzMGirondaPPollockBGDepression following pegylated interferon-alpha: characteristics and vulnerabilityJ Psychosom Res200763213113517662748

- CapuronLRavaudAMillerAHDantzerRBaseline mood and psychosocial characteristics of patients developing depressive symptoms during interleukin-2 and/or interferon-alpha cancer therapyBrain Behav Immun200418320521315050647

- LindsayKLDavisGLSchiffERResponse to higher doses of interferon alfa-2b in patients with chronic hepatitis C: a randomized multicenter trial. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy GroupHepatology1996245103410408903371

- OkanoueTSakamotoSItohYSide effects of high-dose interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis CJ Hepatol19962532832918895006

- FriedMWShiffmanMLReddyKRPeginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infectionN Engl J Med20023471397598212324553

- MulderRTAngMChapmanBRossAStevensIFEdgarCInterferon treatment is not associated with a worsening of psychiatric symptoms in patients with hepatitis CJ Gastroenterol Hepatol200215330030310764032

- RenaultPFHoofnagleJHParkYPsychiatric complications of long-term interferon alfa therapyArch Intern Med19871479157715803307672

- MalaguarneraMDi FazioIRestucciaSPistoneGFerlitoLRampelloLInterferon alpha-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C patients: comparison between different types of interferon alphaNeuropsychobiology199837293979566274

- IinoSHigh dose interferon treatment in chronic hepatitis CGut199334Suppl 2S114S1188314475

- KrausMRSchaferACsefHScheurlenMPsychiatric side effects of pegylated interferon alfa-2b as compared to conventional interferon alfa-2b in patients with chronic hepatitis CWorld J Gastroenterol200511121769177415793861

- MannsMPMcHutchisonJGGordonSCPeginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trialLancet2001358928695896511583749

- ZeuzemSFeinmanSVRasenackJPeginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis CN Engl J Med2000343231666167211106715

- RobaeysGde BieJWichersMCEarly prediction of major depression in chronic hepatitis C patients during peg-interferon alpha-2b treatment by assessment of vegetative-depressive symptoms after four weeksWorld J Gastroenterol200713435736574017963300

- QuarantiniLCBressanRAGalvaoABatista-NevesSParanaRMiranda-ScippaAIncidence of psychiatric side effects during pegylated interferon- alpha retreatment in nonresponder hepatitis C virus-infected patientsLiver Int20072781098110217845538

- AmodioPde ToniENCavallettoLMood, cognition and EEG changes during interferon alpha (alpha-IFN) treatment for chronic hepatitis CJ Affect Disord2005841939815620390

- BanninkMFekkesDvan GoolARInterferon-alpha influences tryptophan metabolism without inducing psychiatric side effectsNeuropsychobiology2007553–422523117873497

- DonnellySPatient management strategies for interferon alfa-2b as adjuvant therapy of high-risk melanomaOncol Nurs Forum19982559219279644709

- CapuronLRavaudAPrediction of the depressive effects of interferon alfa therapy by the patient’s initial affective stateN Engl J Med199934017137010223879

- CastellviPNavinesRGutierrezFPegylated interferon and ribavirin-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: role of personalityJ Clin Psychiatry200970681782819573480

- Dell’OssoLPiniSMaggiLSubthreshold mania as predictor of depression during interferon treatment in HCV+ patients without current or lifetime psychiatric disordersJ Psychosom Res200762334935517324686

- CasteraLZiganteFBastieABuffetCDhumeauxDHardyPIncidence of interferon alfa-induced depression in patients with chronic hepatitis CHepatology200235497897911915051

- DieperinkEHoSBThurasPWillenbringMLA prospective study of neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with interferon-alpha-2b and ribavirin therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis CPsychosomatics200344210411212618532

- HoSBNguyenHTetrickLLOpitzGABasaraMLDieperinkEInfluence of psychiatric diagnoses on interferon-alpha treatment for chronic hepatitis C in a veteran populationAm J Gastroenterol200196115716411197246

- RaisonCLDemetrashviliMCapuronLMillerAHNeuropsychiatric adverse effects of interferon-alpha: recognition and managementCNS Drugs200519210512315697325

- DanAAMartinLMCroneCDepression, anemia and health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis CJ Hepatol200644349149816427157

- FontanaRJBieliauskasLALindsayKLCognitive function does not worsen during pegylated interferon and ribavirin retreatment of chronic hepatitis CHepatology20074551154116317465000

- FontanaRJSchwartzSMGebremariamALokASMoyerCAEmotional distress during interferon-alpha-2B and ribavirin treatment of chronic hepatitis CPsychosomatics200243537838512297606

- HuntCMDominitzJAButeBPWatersBBlasiUWilliamsDMEffect of interferon-alpha treatment of chronic hepatitis C on health-related quality of lifeDig Dis Sci19974212248224869440624

- KrausMRSchaferAFallerHCsefHScheurlenMPsychiatric symptoms in patients with chronic hepatitis C receiving interferon alfa-2b therapyJ Clin Psychiatry200364670871412823087

- MaddockCBaitaAOrruMGPsychopharmacological treatment of depression, anxiety, irritability and insomnia in patients receiving interferon-alpha: a prospective case series and a discussion of biological mechanismsJ Psychopharmacol2004181414615107183

- MajerMWelbergLACapuronLPagnoniGRaisonCLMillerAHIFN-alpha-induced motor slowing is associated with increased depression and fatigue in patients with chronic hepatitis CBrain Behav Immun200822687088018258414

- SchaferAWittchenHUSeufertJKrausMRMethodological approaches in the assessment of interferon-alfa-induced depression in patients with chronic hepatitis C – a critical reviewInt J Methods Psychiatr Res200716418620118188838

- YovtchevaSPRifaiMAMolesJKvan der LindenBJPsychiatric comorbidity among hepatitis C-positive patientsPsychosomatics200142541141511739908

- YatesWRGleasonOHepatitis C and depressionDepress Anxiety1998741881939706456

- JohnsonMEFisherDGFenaughtyAThenoSAHepatitis C virus and depression in drug usersAm J Gastroenterol19989357857899625128

- KenisGPrickaertsJvan OsJDepressive symptoms following interferon-alpha therapy: mediated by immune-induced reductions in brain-derived neurotrophic factor?Int J Neuropsychopharmacol201072917 Epub 2010 Sep 1.

- CapuronLRaisonCLMusselmanDLLawsonDHNemeroffCBMillerAHAssociation of exaggerated HPA axis response to the initial injection of interferon-alpha with development of depression during interferon-alpha therapyAm J Psychiatry200316071342134512832253

- HeinzeSEgbertsFRotzerSDepressive mood changes and psychiatric symptoms during 12-month low-dose interferon-alpha treatment in patients with malignant melanoma: results from the multicenter DeCOG trialJ Immunother201033110611419952950

- SockalingamSAbbeySEAlosaimiFNovakMA review of sleep disturbance in hepatitis CJ Clin Gastroenterol2010441384519730115