Abstract

Introduction

Antipsychotics are recommended as first-line therapy for acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder; however, published literature suggests their real-world use remains limited. Understanding attitudes toward these medications may help identify barriers and inform personalized therapy. This literature review evaluated patient and clinician attitudes toward the use of antipsychotics for treating bipolar disorder.

Materials and methods

A systematic search of the Cochrane Library, Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, and BIOSIS Previews identified English language articles published between January 1, 2000, and June 15, 2016, that reported attitudinal data from patients, health care professionals, or caregivers; treatment decision-making; or patient characteristics that predicted antipsychotic use for bipolar disorder. Results were analyzed descriptively.

Results

Of the 209 references identified, 11 met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated. These articles provided attitudinal information from 1,418 patients with bipolar disorder and 1,282 treating clinicians. Patients’ attitudes toward antipsychotics were generally positive. Longer duration of clinical stability was associated with positive attitudes. Implementation of psychoeducational and adherence enhancement strategies could improve patient attitudes. Limited data suggest clinicians’ perceptions of antipsychotic efficacy and tolerability may have the greatest impact on their prescribing patterns. Because the current real-world evidence base is inadequate, clinician attitudes may reflect a relative lack of experience using antipsychotics in patients with bipolar disorder.

Conclusion

Although data are very limited, perceived tolerability and efficacy concerns shape both patient and clinician attitudes toward use of antipsychotic drugs in bipolar disorder. Additional studies are warranted.

Introduction

Bipolar spectrum disorders (BSDs) consist of many cycling mood disorders, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 2.4% to 15.1%,Citation1,Citation2 comprising bipolar I disorder (BD-I), bipolar II disorder, cyclothymic disorder, and other related disorders. BSD is often complicated by many other comorbidities such as anxiety, substance abuse, and personality disordersCitation3,Citation4 and is associated with a high suicide rate relative to other types of depression.Citation5 Poor treatment adherence and frequent discontinuation of treatment among patients with BSD are common clinical problems and may be responsible for illness chronicity, comorbidity complications, and increased economic burden.Citation3,Citation4 Since the year 2000, numerous second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) have received US Food and Drug Administration approval for first-line treatment of BD-I.Citation6–Citation9 These treatments are approved either as monotherapies or in combination with lithium and/or anticonvulsants.Citation6–Citation8 The most recent guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder recommend antipsychotics as first-line therapy for acute mania and maintenance treatment.Citation4,Citation10–Citation13 Although trends in prescribing patterns show an increase in prescribing of antipsychotics for bipolar disorder over the past decade,Citation14 their real-world use remains limited, and lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilizers remain the standard of care.Citation15–Citation17

Barriers to use of second-generation antipsychotic medications (APs) in bipolar disorder may exist for reasons related to the patient,Citation18,Citation19 clinician,Citation20,Citation21 or health care system.Citation22,Citation23 It is possible that patients and clinicians generally avoid antipsychotics in bipolar disorder because of early reports that described dysphoria or subjective discomfort with first-generation compounds.Citation24–Citation27 Patient- or clinician-related barriers may include tolerability concerns, specifically the increased risk of adverse effects, such as weight gain, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and QT prolongation.Citation28–Citation31 Further, formulary restrictions may lead to prescribing barriers.Citation22,Citation23

Studies have shown that medication satisfaction is positively correlated with treatment adherence, and better adherence is associated with symptom reduction.Citation32,Citation33 However, choosing treatment that is the best fit for patients is a complex process. Clinicians must weigh efficacy benefits versus tolerability concerns based on their familiarity with the drug and available clinical data.Citation20,Citation21,Citation34 Individual patient factors, including preference for a specific treatment modality, treatment history, comorbidities, and adherence history, all need to be considered.Citation34 Factors that affect patient attitudes toward treatment include duration of untreated disease, insight, and past treatment experience.Citation19 This systematic review evaluated the published literature on patient and clinician attitudes toward the use of antipsychotics for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Findings on what patients and clinicians believe to be factors that encourage or discourage the use of this class of drugs may help in understanding the place of these compounds in the bipolar disorder treatment armamentarium and inform personalized therapy for patients with bipolar disorder.

Materials and methods

Search methodology

Systematic searches were performed focused on identifying original research studies and reviews that described barriers and facilitators to prescribing or taking AP for the treatment of bipolar disorder. The Cochrane Library; Ovid MEDLINE® In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; Ovid MEDLINE 1996 to June 15, 2016; Embase 1974 to June 15, 2016; and BIOSIS Previews 1993 to 2016 Week 29 were searched using the following search string: (“bipolar disorder” AND “antipsychotic” NOT “lithium” NOT “valproate”) AND (“barriers” OR “attitudes” OR “prescribing patterns” OR “treatment planning” OR “prescribing” OR “decision-making” OR “treatment choice” OR “awareness” OR “perception” OR “knowledge” OR “experience” OR “treatment satisfaction” OR “stigma”). The searches were limited to English language articles published in peer-reviewed journals between January 1, 2000, and June 15, 2016. The year 2000 was chosen as a cutoff date to ensure clinical relevance of the included articles based on the availability of multiple APs. Eligible articles were also searched by hand to see if there were any additional publications in their reference list that met the initial inclusion criteria.

Article selection process

Authors independently evaluated the articles for eligibility, beginning with the titles (performed by two authors), proceeding to abstracts (each abstract reviewed by two authors, all authors participated), and, lastly, full text (each full-text article reviewed by two authors, all authors participated). Disagreements were resolved by discussion among all authors. Only those articles containing either primary or secondary analyses specific to the bipolar disorder population, including any subgroup analyses specific to patients with this diagnosis, were included. Studies that reported only efficacy or safety, or adherence behavior information without specific attitudinal data from patients, health care professionals, or caregivers were excluded. Review articles and opinion pieces not containing original research data were excluded after their reference lists were searched to identify any new/original research articles not previously identified. Preclinical research, case reports, policy-focused articles, studies in pediatric patients, or those that reported use of antipsychotics in other psychiatric conditions without including bipolar disorder were excluded as well. Descriptive analysis of the selected articles was performed.

Results

Article selection

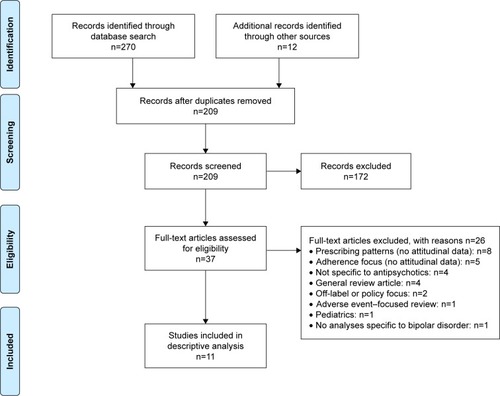

The initial database search retrieved 270 references with another 12 records identified through other sources, including a search by hand (). After duplicates were removed, 209 unique references were screened, and 172 references were excluded after the title and abstract review. The remaining 37 articles were subjected to a full-text review, and 11 articles with attitudinal information from patients with bipolar disorder or clinicians treating patients with bipolar disorder were identified and subsequently analyzed.

Figure 1 PRISMACitation56 flow diagram of study selection.

Abbreviation: PRISMA, preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Study characteristics

Overall, 11 articles reported attitudinal information, representing a total of 1,418 patients with bipolar disorder ()Citation18,Citation19,Citation32,Citation35–Citation37 and 1,282 treating clinicians ()Citation20,Citation34,Citation38–Citation40 from the US, Argentina, and Europe ().Citation18–Citation20,Citation32,Citation34–Citation40 All studies assessing patient attitudes used surveys or validated questionnaires, such as the Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI) and the Attitudes toward Mood Stabilizers Questionnaire (AMSQ). The articles pertaining to clinicians primarily determined attitudes using nonstandardized surveys developed to characterize the decision-making process during drug selection. All standardized instruments used for assessing attitudes toward APs in the studies identified by this search are summarized in .Citation35,Citation41–Citation45

Figure 2 Geographic locations for research conducted.

Table 1 Overview of studies assessing patient attitudes toward antipsychotics for bipolar I disorder

Table 2 Overview of studies assessing clinician attitudes toward antipsychotics for bipolar I disorder

Table 3 Standardized instruments used to assess patient and clinician attitudes toward antipsychotics

Patient attitudes

Although the data are limited, articles reporting patient attitudes suggest that the majority of patients with bipolar disorder have positive attitudes toward antipsychotic treatmentCitation18 and that negative attitudes are generally held by those who have poor insight regarding their illness or less stable disease.Citation19 Available data also indicate that positive attitudes toward medications are associated with better adherenceCitation32 and that educational strategies may improve attitudes toward medication and, in turn, improve adherence.Citation35,Citation37

The Jorvi Bipolar Study,Citation18 a naturalistic study conducted in Finnish patients with bipolar disorder type I or II, assessed patient attitudes toward various types of treatment, including antipsychotics. For the 176 patients followed during the first 6 months of this study, most (86.9%) received mood stabilizers or SGAs. Of 106 patients who provided responses, 7.5% reported having a negative attitude toward antipsychotics that would prevent them from using this treatment. At 18 months of follow-up, ~29% of those taking antipsychotics reported nonadherence, of which >20% was attributed to a generally negative attitude toward treatment. Results from this study suggest that negative attitudes toward antipsychotic treatment can increase the likelihood of nonadherence more than sevenfold, based on an odds ratio comparing those with negative versus positive attitudes. However, overall, patients reported positive attitudes toward antipsychotics, similar to their attitudes regarding other treatments for bipolar disorder (eg, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and anxiolytics).

Bates et alCitation32 found that patient satisfaction with medication, as assessed by the Satisfaction with Antipsychotic Medication (SWAM) scale, was positively associated with treatment adherence. These investigators recruited patients who participated in the 2006 and 2007 US National Health and Wellness Survey. A total of 1,052 patients who self-reported a diagnosis of bipolar disorder and had a Composite International Diagnostic Interview–bipolar disorder score of ≥7 (indicating higher risk for bipolar disorder) and did not have schizophrenia were surveyed to determine attitudes toward current medication. Patient adherence was measured using the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale. The majority of patients in this cross-sectional sample, both adherent and nonadherent, were female (>75%), and 47% and 2% were being treated with second- and first-generation antipsychotics, respectively. Overall, patients who reported satisfaction with their AP, as measured by the SWAM, were 2.4 times as likely to be adherent as patients who were dissatisfied.

In a cross-sectional study conducted in Spain, Medina et alCitation19 assessed attitudes toward antipsychotics among inpatients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Forty-one patients with bipolar disorder who were admitted for an acute manic episode were included, though only limited results were reported separately for this group. Using the 10-item DAI (DAI-10), a true–false self-report instrument that assesses patients’ experience with psychotropic medications,Citation43,Citation46,Citation47 and the Rating of Medication Influences (ROMI), a scale that assesses subjective reasons for adherence or nonadherence,Citation44 these investigators found that patients with bipolar disorder who exhibited positive attitudes toward treatment (n=35) had a significantly longer duration of clinical stability (ie, an event-free period) versus those with negative attitudes (n=6; mean difference in stability time, 2.9 years; P=0.0012).

Only one study reported negative attitudes toward specific psychotropic drugs.Citation36 In a letter to the editor, Strejilevich and BonettoCitation36 briefly described subjective findings from a survey they conducted among 100 Argentinian patients with bipolar disorder. When patients were asked about their experience related to treatment, haloperidol and trifluoperazine were the drugs most commonly associated with the worst memories (86% and 24% of patients, respectively). The authors note, however, that more recent data suggest better subjective tolerability with newer SGAs.

Two studies monitored patients’ attitudes toward medication before and after specific psychosocial and educational interventions.Citation35,Citation37 Ventriglio et alCitation37 used the 30-item DAI (DAI-30) to prospectively evaluate the effects of psycho-education on medication attitudes among 33 patients with BD-I and 33 with schizophrenia from a single center in Italy. Education was aimed at increasing awareness of the patient’s respective psychiatric illness as well as general health, diet, exercise, weight control, and current treatment. Results following the intervention were reported separately for the two diagnoses. Most of the patients with BD-I were receiving antipsychotics (97.0%), and no change in mean dosing was observed during the study. At the 6-month follow-up assessment, patients with BD-I showed a significantly improved DAI-30 score (+0.432; P<0.0001).

In the second study, Levin et alCitation35 conducted an analysis of medication adherence and attitudes assessed before and after Customized Adherence Enhancement (CAE), a needs-based adherence enhancement psychosocial intervention. Data were extracted from three studies, two of which each enrolled 43 poorly adherent patients with bipolar disorder, each from different clinical settings in the US (ie, a com-munity mental health center or an academic medical center), who were receiving SGAs and/or mood stabilizers, as well as a third cohort of patients with schizophrenia (n=10) or schizoaffective disorder (n=20).Citation48,Citation49 Medication adherence and attitudes assessed before and after CAE using the Tablet Routines Questionnaire, AMSQ, the ROMI, and the DAI-10, demonstrated improvements in medication adherence and in most of the medication attitude scales.Citation35

Our review found seven articles (64%) that included attitudinal data pertaining to patients with bipolar disorder in addition to patients with other psychiatric illnesses,Citation19,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37–Citation40 yet only five of these included survey questions or statistical analyses in the subgroup of patients with bipolar disorder.Citation19,Citation34,Citation37,Citation39 The remaining two articles provided only descriptive attitudinal data specific to patients with bipolar disorder, without further analyses in this subgroup.Citation35,Citation38 Two of the articles that assessed patients’ subjective attitudes toward antipsychotics offered overarching conclusions for patients with bipolar disorder combined with those with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder despite inherent differences in these conditions,Citation19,Citation35 though Levin et alCitation35 performed analyses of covariance confirming no significant effect of diagnosis on any of the attitudinal measures.Citation35

Clinician attitudes

Based on the articles identified in this search, information regarding clinician attitudes toward APs appears to be limited and comes largely from surveys that did not use standardized instruments. The literature suggests that clinicians perceive antipsychotic efficacy and tolerability as varying across patients and that there is a need for personalization of treatment regimens based on patient clinical needs.Citation34,Citation38

A European survey of psychiatrists in the UK, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands examined perceptions about antipsychotic drug therapy among 363 psychiatrists from a variety of practice settings, primarily offices/private consulting (31%), hospitals (23%), and outpatient clinics (20%).Citation34 Responses were based on physicians’ notes from 1,442 patients with schizophrenia (53%) or bipolar disorder (47%). Results suggested that, overall, physicians perceive significant differences in efficacy and tolerability between the SGAs, and the most common reasons for sequential prescribing of these drugs in patients with bipolar disorder were avoidance of specific side effects (90%), consideration of treatment history (92%), patient discontinuation or nonadherence (84%), and the presence of specific clinical symptoms (80%). Overall, the authors concluded that tailoring therapy should involve consideration of a variety of factors, including a patient’s previous medication experience, comorbidities, current symptoms, environment, and medication tolerability.

In a position paper published by a panel of Italian psychiatry experts, guidance is offered regarding the optimal strategy for switching to the SGA aripiprazole.Citation38 Similar to the findings from the survey research described earlier, these authors highlight the need to consider factors such as patient characteristics, illness, medication, and environment, and note that medications should be evaluated individually when making the decision to switch between antipsychotics.

A survey of 718 European psychiatrists in the UK, Germany, France, Italy, and Spain, 67% of whom were practicing in the hospital setting, specifically assessed how metabolic concerns influence psychiatrists’ opinions regarding the treatment of bipolar disorder.Citation20 The potential for weight gain was identified as the most common concern, and respondents reported this was also their patients’ top concern. The majority of psychiatrists associated several of the evaluated antipsychotics with weight gain, most often olanzapine (94%) and risperidone (72%). The authors note this is a significant finding not only because of increased cardiovascular risk but because weight gain can lead to nonadherence.

Two additional articles provide further insight regarding factors that drive psychiatrists’ pharmacotherapy decision-making in the treatment of bipolar disorder.Citation39,Citation40 Goldberg et alCitation39 conducted a survey of the membership of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology to determine consensus on sequential treatment steps for major depression and bipolar disorder. A total of 154 responses were received, primarily from clinicians who were directly involved in patient care ≥75% of their time (71%).Citation39 All respondents reported prescribing SGAs for bipolar depression, and 90% believed they provide a moderate to marked response. When asked which clinical factors influenced prescribers away from using an antidepressant for bipolar depression, 89% indicated rapid cycling was a key consideration, and SGAs were a preferred first-line treatment in this patient group by 24% of respondents. In addition, when asked about preferred first-line agents for treating bipolar disorder during pregnancy, SGAs were most commonly selected (45% of respondents); the next most frequently selected first-line treatments were lamotrigine (35%) and FGAs (21%).

In the second article, Llorca et alCitation40 report results from a 32-item questionnaire completed by experts from the French Association for Biological Psychiatry and Neuropsychopharmacology during development of treatment guidelines for the use of long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics in serious mental illnesses, specifically schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and bipolar disorder.Citation40 A consensus rating scale was used in which respondents expressed levels of agreement or disagreement with survey questions, and these responses were then interpreted as recommended indications for first-, second-, or third-line treatment strategies for each diagnosis. The majority of respondents (54.8%) felt that patients with bipolar disorder could benefit from a second-generation LAI (monotherapy or in combination) as second-line therapy. These guidelines specifically recommended second-generation LAI antipsychotics as second-line treatment for patients with BD-I, manic polarity, rapid-cycling bipolar disorder, and low insight as well as those who pose a risk to others. First- or second-generation LAI antipsychotics were recommended as first-line treatment for patients who exhibited partial/full nonadherence and those who preferred these therapies.

Similarly, among the articles describing clinician attitudes, one provided overall conclusions that combined patients with bipolar disorder and those with schizophrenia,Citation34 but did include a separate discussion of the top considerations for psychiatrists choosing between SGAs for bipolar disorder, namely, side effects, and patient treatment history.

Discussion

Our review suggests that assessing patient attitudes toward medication and implementing strategies to combat those that may be based on inaccurate or inadequate knowledge could help maintain adherence and improve long-term outcomes. Two studies reported in this review found that specific educational strategies can improve patient attitudes toward medications.Citation35,Citation37 Targeting specific negative attitudes or reasons for poor adherence can potentially improve attitudes and may ultimately lead to better adherence, as highlighted by the two longitudinal studies of Levin et al,Citation50 which demonstrated that patients whose medication attitudes improved became more adherent to treatment.

It is important to note that caregiver attitudes toward treatment can also play a key role in medication attitudes and adherence in general,Citation51,Citation52 as reported by Chang et alCitation51 who in a cross-sectional study investigated 200 outpatients with a chronic psychiatric disorder and their caregivers about their attitudes toward psychotropic medications. This study revealed that additional factors that shape both patient and caregiver attitudes toward medications include perceived risks and benefits of the treatment, necessity for taking medication, and costs. In another cross-sectional analysis, Chang et alCitation51 evaluated the relationship between medication attitudes and a number of patient-related variables. Patients with more positive attitudes toward medication had better social support and believed more strongly that others, such as family or clinicians, determine their health outcomes. Although further work is needed to assess how both patient and caregiver medication attitudes directly affect adherence,Citation51,Citation52 current evidence generally suggests that it is beneficial to include caregivers in education and support focused on medication prescribing and medication taking.

This review found that clinician perceptions of drug-specific efficacy, tolerability, and adverse effects impact their attitudes toward antipsychotics. It is worth noting, however, that clinician attitudes were not specifically assessed using standardized attitude questionnaires. Although none of the articles used an attitude-specific measure for evaluation, general perceptions in the form of recommendationsCitation39,Citation40 and prescribing behaviorsCitation34 gave some insight into clinicians’ attitudes toward antipsychotic use for bipolar disorder. Clinicians mainly focused on drug characteristics (eg, efficacy, pharmacologic activity, and tolerabilityCitation20,Citation38) and patient comorbidities and potential propensity to experience side effects (eg, weight, medical historyCitation20,Citation38) to guide their treatment decisions and prescribing patterns.Citation20 Perceived tolerability of individual treatments, particularly potential metabolic risks, strongly affected treatment choice.

Overall, this review found few published studies addressing patient or clinician attitudes toward antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Many articles did not include attitudinal data as a primary outcome, and all had methodological limitations such as cross-sectional design, which prohibits causal interpretation, or a relatively short follow-up period, which precludes generalization to long-term treatment regimens that are the norm for bipolar disorder.

Although one study in this review reported negative patient attitudes associated with specific first-generation antipsychotics (haloperidol and trifluoperazine),Citation36 it should be noted that this study may have limited current clinical relevance since it was conducted in 1999 and published over a decade ago. Numerous SGA treatments have been approved for use in bipolar disorder in the past 15 years. The bipolar clinical trial evidence base for the second-generation compounds is robust, and these agents generally have a decreased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms compared with first-generation compounds.Citation6,Citation28,Citation53 Several of the articles identified in this review failed to distinguish between first-generation antipsychotics and SGAs. Interpretations regarding patient attitudes specific to first-generation antipsychotics are especially limited because in the two articles that assessed attitudes toward these agents either few patients were taking this class of antipsychotics (1.7% of the patient sample)Citation32 or the data were derived >15 years ago with little detail on study methodology.Citation36 Clinician attitude articles similarly had limited focus on first-generation drugs. Importantly, because of the overall lack of distinction between older and newer antipsychotics, along with the overall limited number of studies identified, some of which included very small numbers of patients with bipolar disorder, findings from this review may not be generalizable to the first-generation antipsychotics.

More than half of the articles identified in this review did not distinguish the subtypes of bipolar disorder in the patient sample (54.5%).Citation19,Citation20,Citation32,Citation34–Citation36 This is a well-known limitation of the available literature, as noted in treatment guidelines, leading to uncertainty regarding whether subtypes of patients with bipolar disorder may respond differently to treatments.Citation12 Likewise, it is unclear whether patients with different subtypes of bipolar disorder may have differing attitudes toward antipsychotic treatment. For example, individuals with a history of manic psychosis and hospitalization might potentially have negative thoughts or memories of antipsychotics, while individuals with no history of frank mania who are receiving antipsychotic treatment for long-term mood stabilization may have a very different experience. In addition, the inclusion of patients with a self-reported diagnosis of bipolar disorderCitation32 adds uncertainty to generalization of the findings.

Given that data specific to the use of antipsychotics for bipolar disorder are limited, it is possible that the findings regarding clinician attitudes may, in part, reflect a relative lack of experience using antipsychotics in this patient population, drawing attention to the larger issue that few data are available to support evidence-based decisions in this area. As prescribing patterns for bipolar disorder are reported to be changing in some settings, with antipsychotics increasingly prescribed,Citation14,Citation54 additional evidence on both patient and clinician attitudes toward antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of bipolar disorder will likely accumulate over time.

After performing this systematic review of current literature, numerous research gaps were identified. As newer SGAs become approved for treating people with bipolar disorder, there remain scant high-quality data regarding patient, provider, or caregiver attitudes toward their use. The majority of the literature regarding attitudes toward bipolar disorder treatments is focused on lithium and anticonvulsants, while attitudes toward antipsychotics are primarily found in the schizophrenia literature. Although this review of the literature provides some insight into current patient and clinician attitudes, a comprehensive and prospective evaluation of factors that influence antipsychotic drug attitudes in bipolar disorder has not been conducted. There is a need for well-designed, real-world studies using standardized, validated questionnaires to collect additional attitudinal data that can be placed into clinical context, with an emphasis on understanding how medication attitudes influence treatment decisions in bipolar disorder. Additional studies that evaluate clinician and patient attitudes toward specific drugs, drug classes, and different drug formulations (eg, LAI antipsychotics) in bipolar disorder may help to identify ways to optimize adherence, satisfaction with care, and long-term outcomes.

As with any systematic review, our analysis had several limitations. Our search was limited to articles written in English; potentially relevant articles published in other languages were not captured. Although a comprehensive list of search terms was designed to retrieve all publications regarding attitudes toward antipsychotics for bipolar disorder, a search done by hand retrieved additional pertinent references, indicating that some publications meeting our search criteria may not have been captured and evaluated. Although there were few articles meeting the predefined inclusion criteria, we believe that the risk of publication bias with a broad, drug-class wide attitudinal analysis such as ours is likely lower compared to publications on studies focused on efficacy or safety of specific drugs. Moreover, the results are specific to antipsychotics in bipolar disorder and cannot be compared with or generalized to attitudes toward other treatments for bipolar disorder. Further, the articles could not be directly compared because their studies had varying designs, end-points, and attitude evaluation methods (eg, surveys versus interviews; numerous questionnaires [DAI, ROMI, SWAM, AMSQ]). Lastly, given the limited quantity of data and the lack of consistent methodology, a meta-analysis could not be performed to quantify differences. We used the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) approachCitation55 to guide our literature review, although there are other guidelines that may have been appropriate as well, such as enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ).Citation56

Conclusion

In conclusion, there remains a dearth of information regarding patient and clinician attitudes toward the use of antipsychotics for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Understanding attitudes may help overcome barriers, meet treatment expectations, and confer greater treatment adherence. Additional real-world studies are warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. Editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Jessica Holzhauer, DVM, and Sheri Arndt, PharmD, of C4 MedSolutions, LLC (Yardley, PA), a CHC Group company, with funding from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Disclosure

Martha Sajatovic has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Reinberger Foundation, Reuter Foundation, and the Woodruff Foundation; has been a consultant for Bracket, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Pfizer, Prophase, and Supernus; has received royalties from Johns Hopkins University Press, Lexicomp, Oxford University Press, Springer Press, and UpToDate; and has participated in CME activities for the American Physician Institute, CMEology, and MCM Education. Faith DiBiasi and Susan N Legacy are employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Dell’AglioJCJrBassoLAArgimonIIArtecheASystematic review of the prevalence of bipolar disorder and bipolar spectrum disorders in population-based studiesTrends Psychiatry Psychother20133529910525923299

- MerikangasKRJinRHeJPPrevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiativeArch Gen Psychiatry201168324125121383262

- FagioliniAForgioneRMaccariMPrevalence, chronicity, burden and borders of bipolar disorderJ Affect Disord20131482–316116923477848

- FountoulakisKNGrunzeHVietaEThe International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) treatment guidelines for Bipolar disorder in adults (CINP-BD-2017), part 3: the clinical guidelinesInt J Neuropsychopharmacol Epub20161210

- LatalovaKKamaradovaDPraskoJSuicide in bipolar disorder: a reviewPsychiatr Danub201426210811424909246

- KetterTACitromeLWangPWCulverJLSrivastavaSTreatments for bipolar disorder: can number needed to treat/harm help inform clinical decisions?Acta Psychiatr Scand2011123317518921133854

- Abilify® (aripiprazole) [prescribing information]Tokyo, JapanOtsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd2016

- Saphris® (asenapine) [prescribing information]St. Louis, MOForest Pharmaceuticals, Inc2015

- US Food and Drug AdministrationApproval package for: application number NDA 20-592/S-006 Zyprexa oral tablets2000 Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2000/020592_S006_ZUPREXA_ORAL_TABS_AP.pdfAccessed December 1, 2016

- GoodwinGMConsensus Group of the British Association for PsychopharmacologyEvidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised second edition – recommendations from the British Association for PsychopharmacologyJ Psychopharmacol200923434638819329543

- MalhiGSBassettDBoycePRoyal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disordersAust N Z J Psychiatry201549121087120626643054

- American Psychiatric AssociationPractice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, second edition2002 Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar.pdfAccessed July 21, 2016

- American Psychiatric AssociationGuideline watch: practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, second edition2005 Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar-watch.pdfAccessed November 22, 2016

- KessingLVVradiEAndersenPKNationwide and population-based prescription patterns in bipolar disorderBipolar Disord201618217418226890465

- HirschowitzJKolevzonAGarakaniAThe pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder: the question of modern advancesHarv Rev Psychiatry201018526627820825264

- KarantiAKardellMLundbergULandenMChanges in mood stabilizer prescription patterns in bipolar disorderJ Affect Disord2016195505626859073

- MiuraTNomaHFurukawaTAComparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysisLancet Psychiatry20141535135926360999

- ArvilommiPSuominenKMantereOLeppamakiSValtonenHIsometsaEPredictors of adherence to psychopharmacological and psychosocial treatment in bipolar I or II disorders – an 18-month prospective studyJ Affect Disord201415511011724262639

- MedinaESalvaJAmpudiaRMaurinoJLarumbeJShort-term clinical stability and lack of insight are associated with a negative attitude towards antipsychotic treatment at discharge in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorderPatient Prefer Adherence2012662362922969293

- BauerMLecrubierYSuppesTAwareness of metabolic concerns in patients with bipolar disorder: a survey of European psychiatristsEur Psychiatry200823316917718160267

- CampbellECDeJesusMHermanBKA pilot study of antipsychotic prescribing decisions for acutely-Ill hospitalized patientsProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry201135124625121108980

- SeaburySAGoldmanDPKalsekarISheehanJJLaubmeierKLakdawallaDNFormulary restrictions on atypical antipsychotics: impact on costs for patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in MedicaidAm J Manag Care2014202e52e6024738555

- VogtWBJoyceGXiaJDiraniRWanGGoldmanDPMedicaid cost control measures aimed at second-generation antipsychotics led to less use of all antipsychoticsHealth Aff (Millwood)201130122346235422147863

- HoganTPAwadAGEastwoodMREarly subjective response and prediction of outcome to neuroleptic drug therapy in schizophreniaCan J Psychiatry19853042462482861887

- AwadAGHoganTPVorugantiLNHeslegraveRJPatients’ subjective experiences on antipsychotic medications: implications for outcome and quality of lifeInt Clin Psychopharmacol199510Suppl 3123132

- AwadAGVorugantiLNImpact of atypical antipsychotics on quality of life in patients with schizophreniaCNS Drugs2004181387789315521791

- VorugantiLNAwadAGSubjective and behavioural consequences of striatal dopamine depletion in schizophrenia – findings from an in vivo SPECT studySchizophr Res2006881–317918616949796

- HaddadPMSharmaSGAdverse effects of atypical antipsychotics: differential risk and clinical implicationsCNS Drugs2007211191193617927296

- MuenchJHamerAMAdverse effects of antipsychotic medicationsAm Fam Physician201081561762220187598

- CentorrinoFMastersGATalamoABaldessariniRJOngurDMetabolic syndrome in psychiatrically hospitalized patients treated with antipsychotics and other psychotropicsHum Psychopharmacol201227552152622996619

- GentileSLong-term treatment with atypical antipsychotics and the risk of weight gain: a literature analysisDrug Saf200629430331916569080

- BatesJAWhiteheadRBolgeSCKimECorrelates of medication adherence among patients with bipolar disorder: results of the Bipolar Evaluation of Satisfaction and Tolerability (BEST) study: a nationwide cross-sectional surveyPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry2010125

- Liu-SeifertHOsuntokunOOGodfreyJLFeldmanPDPatient perspectives on antipsychotic treatments and their association with clinical outcomesPatient Prefer Adherence2010436937721049089

- AltamuraACArmadorosDJaegerMKernishRLocklearJVolzHPImportance of open access to atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a European perspectiveCurr Med Res Opin20082482271228218588748

- LevinJBSeifiNCassidyKAComparing medication attitudes and reasons for medication nonadherence among three disparate groups of individuals with serious mental illnessJ Nerv Ment Dis20142021176977325357252

- StrejilevichSGarcia BonettoGSubjective responses to pharmacological treatments in bipolar patientsJ Affect Disord200377219119214607397

- VentriglioAGentileABaldessariniRJImprovements in metabolic abnormalities among overweight schizophrenia and bipolar disorder patientsEur Psychiatry201429740240724439513

- FagioliniABrugnoliRDi SciascioGDe FilippisSMainaGSwitching antipsychotic medication to aripiprazole: position paper by a panel of Italian psychiatristsExpert Opin Pharmacother201516572773725672664

- GoldbergJFFreemanMPBalonRThe American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology survey of psychopharmacologists’ practice patterns for the treatment of mood disordersDepress Anxiety201532860561326129956

- LlorcaPMAbbarMCourtetPGuillaumeSLancrenonSSamalinLGuidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illnessBMC Psychiatry20131334024359031

- HarveyNSThe development and descriptive use of the Lithium Attitudes QuestionnaireJ Affect Disord19912242112191939930

- ScottJPopeMNonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictorsJ Clin Psychiatry200263538439012019661

- AwadAGSubjective response to neuroleptics in schizophreniaSchizophr Bull19931936096187901897

- WeidenPRapkinBMottTRating of medication influences (ROMI) scale in schizophreniaSchizophr Bull19942022973107916162

- RofailDGrayRGournayKThe development and internal consistency of the satisfaction with Antipsychotic Medication ScalePsychol Med20053571063107216045072

- HoganTPAwadAGDrug attitude inventoryRushAHandbook of Psychiatric MeasuresArlington, VAAmerican Psychiatric Association Publishing2000

- TeterCJFaloneAEBakaianAMTuCOngurDWeissRDMedication adherence and attitudes in patients with bipolar disorder and current versus past substance use disorderPsychiatry Res20111902–325325821696830

- SajatovicMLevinJFuentes-CasianoECassidyKATatsuokaCJenkinsJHIllness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medicationCompr Psychiatry201152328028721497222

- SajatovicMLevinJTatsuokaCSix-month outcomes of customized adherence enhancement (CAE) therapy in bipolar disorderBipolar Disord201214329130022548902

- LevinJBTatsuokaCCassidyKAAebiMESajatovicMTrajectories of medication attitudes and adherence behavior change in non-adherent bipolar patientsCompr Psychiatry201558293625617964

- ChangCWSajatovicMTatsuokaCCorrelates of attitudes towards mood stabilizers in individuals with bipolar disorderBipolar Disord201517110611224974829

- GroverSChakrabartiSSharmaATyagiSAttitudes toward psychotropic medications among patients with chronic psychiatric disorders and their family caregiversJ Neurosci Rural Pract20145437438325288840

- LeuchtSCiprianiASpineliLComparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysisLancet2013382989695196223810019

- Walpoth-NiederwangerMKemmlerGGrunzeHTreatment patterns in inpatients with bipolar disorder at a psychiatric university hospital over a 9-year period: focus on mood stabilizersInt Clin Psychopharmacol201227525626622842799

- LiberatiAAltmanDGTetzlaffJThe PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaborationBMJ2009339b270019622552

- TongAFlemmingKMcInnesEOliverSCraigJEnhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQBMC Med Res Methodol20121218123185978