Abstract

Objective

The aim of the current study was to evaluate whether cognitive behavioral group therapy has a positive impact on psychiatric, and motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Methods

We assigned 20 PD patients with a diagnosis of psychiatric disorder to either a 12-week cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) group or a psychoeducational protocol. For the neurological examination, we administered the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale and the non-motor symptoms scale. The severity of psychiatric symptoms was assessed by means of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, and the Clinical Global Impressions.

Results

Cognitive behavioral group therapy was effective in treating depression and anxiety symptoms as well as reducing the severity of non-motor symptoms in PD patients; whereas, no changes were observed in PD patients treated with the psychoeducational protocol.

Conclusion

CBT offered in a group format should be considered in addition to standard drug therapy in PD patients.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurological disorder mainly characterized by bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor. The majority of PD patients also experience non-motor and psychological symptoms, including depression, anxiety, apathy, psychosis, and impulse control disorders.Citation1,Citation2 Depressive and anxiety symptoms occur in up to 50% of PD patients and are also associated with poorer quality of life.Citation3,Citation4

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most well-established interventions in reducing both depression and anxiety. Several studies have investigated the efficacy of individual CBT on psychiatric disorders in PD.Citation5,Citation6 By contrast, only a handful of studies have evaluated the efficacy of CBT groups on psychiatric disorders in PD patients.Citation5–Citation9 Group CBT may be useful in the adaptation process in patients affected by a chronic degenerative disease. In PD, the disease may elicit psychological reactions that are expressed in the form of phenomena of biological activation, and of subjective experiences of behavioral reactions and psychiatric symptoms (particularly anxiety and depressive symptoms). In a previous open study, in which we investigated the effect of a group CBT intervention in PD patients, we found that group CBT was useful for treating psychiatric and neurological symptoms.Citation10 However, the efficacy of group CBT in PD patients needs to be confirmed by controlled studies. Currently, no study has compared the effects of group CBT with the effect produced with a psychoeducational protocol in PD patients. In view of earlier findings of the efficacy of individual and group CBT, we conducted a clinical study to investigate the effect of group CBT in PD patients and we compared the results with those obtained with PD patients treated with a psychoeducational protocol.

The primary outcome of the study was to assess the possible improvement in psychiatric symptoms as measured by several rating scales in CBT group therapy and psychoeducational intervention. The secondary outcomes were the effect of CBT group therapy and psychoeducational intervention on motor and non-motor symptoms in PD patients.

Methods

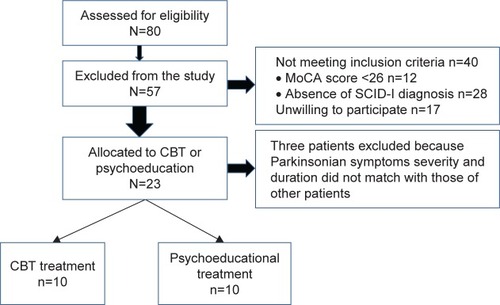

We recruited 20 PD patients from the outpatient clinic for Movement Disorders of the Department of Neurology and Psychiatry, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy. Patients were enrolled if they had a psychiatric diagnosis based on the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I). Exclusion criteria included comorbid psychiatric diagnoses of Axis-I psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder, as well as an education level of less than middle high school. We also excluded patients with possible substance use disorders (). After a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. The local ethics committee approved the study (Ethical Committee Sapienza University of Rome). Participants received the study treatment at no cost. Psychiatric and neurological evaluations were performed before and after the interventions.

Figure 1 Participants’ flow diagram.

The diagnosis of PD was made according to the European Federation of Neurological Society and Movement Disorders Society criteria.Citation11 The severity of PD was scored according to the Hoehn and Yahr (HY) Scale,Citation12 the severity of motor symptoms was assessed by means of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, part III (UPDRS-III)Citation13 and the quality of life was assessed using the Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire (PDQ8).Citation14 Non-motor symptoms (NMS) were assessed by means of the Non-Motor Symptom Scale.Citation15 Cognitive function was measured using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale (MoCA)Citation16 and the Frontal Assessment Battery Scale (FAB).Citation17 To be able to conduct a reliable SCID-I,Citation18 we only enrolled patients without evidence of cognitive impairment (MoCA score >26).

The psychiatric evaluation was performed by two trained psychiatrists and was based on the SCID-I for Axis-I disorders and the SCID-II for Axis-II disorders. The severity of psychiatric symptoms was assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D),Citation19 the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A),Citation20 the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),Citation21 and the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI).Citation22 To assess the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms, we used the cut-off scores recommended for the HAM-D-7 (8–13, mild; 14–18, moderate; ≥19, severe) and for the HAM-A (≤17, mild; 18–24, moderate; ≥24, severe). All of the PD patients were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. Apathy was rated using the apathy evaluation scale.Citation23

Patients were pseudorandomized to one of the two groups of treatment by matching duration and severity of Parkinson disease and homogeneity in psychiatric clinical diagnosis. In our study, 10 of the 20 PD patients were assigned to group CBT and 10 to the psychoeducational protocol (psychoeducational group). The neurological and psychiatric evaluations were performed at baseline and at the end of the group intervention (12 weeks) in the group CBT, and at baseline and at the end of the psychoeducational intervention in the psychoeducational group (12 weeks). The baseline and final assessments were conducted by a neurologist and psychiatrist who were blind to the type of intervention.

CBT group

A CBT-trained psychiatrist and a neurologist conducted the CBT sessions. The CBT intervention consisted of 12 weekly 90-minute sessions of group therapy.Citation24 The therapists involved in the CBT group received weekly supervision and training. The group CBT administered to the patients was standard group CBT,Citation25,Citation26 the only difference being that attention was paid to the link between psychological distress and physical illness.Citation27,Citation28 Important elements of the group CBT sessions included a convincing rationale for the intervention, training in practical skills to change mood-related thoughts, behaviors and PD motor symptoms, an encouraging practice of the skills outside the therapy sessions, and the attribution of improvement to the use of the skills.Citation29 We also evaluated specific aspects, including the tendency to avoid social situations, family conflict, and low levels of assertiveness and self-sufficiency. In addition, several sessions were devoted to problem-solving, coping strategies, and modeling.Citation30

Psychoeducational group

The psychoeducational group met every 2 weeks. A psychiatrist and a neurologist (different from those who conducted the CBT group) conducted the psychoeducational sessions. The interventions focused on information and explanations concerning the neurological disease and the possible effects on patients’ psychological world. Four main areas were targeted: illness awareness; adherence to treatment; early detection of motor and non-motor symptoms; and lifestyle regularity. Each session began with a 30–40 minute presentation on the topic of the day, followed by a related exercise and concluded with a group discussion. Although the principal goal of psychoeducation for PD was to provide accurate and reliable information regarding the disease course and therapeutic strategies, additional objectives included teaching patients’ self-management skills and helping them make informed decisions about their own management within the context of a collaborative working relationship with their clinical team. Some sessions were focused on side effects of PD medication. Other sessions included an explanation of motor complications and other side effects, such as impulsive and compulsive behavior, hallucinations, and delusions. When possible, psychoeducational interventions were also personalized, for example, by taking into account the individual’s unique pattern of illness, their risk factors for relapse, and their current social circumstances.

All variables are expressed as mean ± SD. Differences in age, years of education and gender between PD patients allocated to the CBT group therapy and PD patients allocated to the psychoeducational group were evaluated by means of the Mann–Whitney U test. Non-parametric tests (ie, Mann–Whitney U test and Wilcoxon sum square test) were used to identify potential differences between the two groups in the mean baseline values of the psychiatric and neurological rating scales, and to identify any differences within each group in the psychiatric and neurological rating scale scores before and after the interventions. Bonferroni’s correction was applied to multiple comparisons. All p-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 13.0.

Results

One of the 10 patients assigned to the group CBT, and one of the 10 patients assigned to the psychoeducational group did not complete the protocol. Therefore, we analyzed data for nine patients in the CBT group and nine patients in the psychoeducational group who participated in all the sessions of the study ().

Table 1 Demographic and clinical data of patients with Parkinson’s disease who completed the interventions

Patients being treated with antiparkinsonian drugs continued their treatment throughout the study, and all of the patients were examined while they were on their usual drug treatment regimen. One patient in the group CBT and one in the psychoeducational group had been on antidepressant therapy for approximately a year prior to starting the study; this medication treatment continued unchanged throughout the study.

Neurological features before and after interventions

There were no differences in UPDRS-III and NMS scores at baseline among patients who underwent the CBT treatment and those who were randomized to the psychoeducational protocol (, S1, and S2). There were also no differences found in UPDRS scores between the two groups at the end of the two treatments (). The NMS total score improved significantly in the CBT group, but not in the psychoeducational group (). There were no significant differences before and after CBT therapy in any of the variables of the NMS scale, and only differences in the total score were significant.

Table 2 Effect of CBT and psychoeducational interventions on neurological symptoms and quality of life

Psychiatric features before and after interventions

At baseline evaluation, psychiatric diagnoses based on the SCID-I interview revealed that patients randomized to the CBT treatment and patients randomized to the psychoeducational protocol had similar psychiatric burden (). Similarly, the severity of psychiatric symptoms was also comparable between patients who participated in the CBT treatment and those who participated in the psychoeducational treatment (). The SCID-II interview did not reveal any diagnoses in either group.

Table 3 Effect of CBT and psychoeducational interventions on psychiatric rating scales

The HAM-A scores, the HAM-D scores, and the BPRS scores improved significantly in the CBT group from baseline to the end of the treatment; whereas, these symptoms did not decrease among PD patients in the psychoeducational group (). The apathy score also improved significantly in the CBT group (). Regarding the CGI scores, in the CBT group at baseline, three patients had a score of 4, and six patients had a score of 6; whereas at the end of treatment, five patients had a score of 3, three patients a score of 2, and one patient had a score of 0. In the psychoeducational group, at baseline four patients had a score of 4 and five patients had a score of 3, and the scores remained unchanged at the end of the treatment. When assessing individual scores on the psychiatric rating scales and the CGI scores, we found that all participants in the CBT group improved; whereas, scores in these domains for participants in the psychoeducational group remained stable.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrated that among PD patients in the CBT group, scores on the HAM-A decreased by 30%, HAM-D scores decreased by 22%, BPRS scores were reduced by 18.0%, and apathy score decreased by 15%, revealing that all patients treated with group CBT improved with regard to their psychiatric functioning. NMS scores were also significantly improved in the CBT group. Conversely, no changes in these measures were observed in the psychoeducational group. We also found that the UPDRS-III did not change significantly following the CBT group intervention or the psychoeducational group.

All the patients were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder according to the SCID-I, and the patients’ HAM-A, HAM-D, and BPRS scores were all above the cut-off and considered pathological. Therefore, it is unlikely that the differences between the CBT and the psychoeducational group were due to the variation in clinical severity of psychiatric disturbances.

The results of the present study are in keeping with those of previous studies investigating individual CBT for depression in PD patients.Citation5 Few studies have evaluated the efficacy of group CBT for psychiatric symptoms among individuals with PD. Two such studies without a control group showed an improvement in anxiety and depression symptoms following group CBT;Citation10,Citation31 whereas other studies used a wait-list control group.Citation32,Citation33 Our study demonstrated that group CBT improves psychiatric symptoms in PD patients when compared to those receiving a psychoeducational intervention. Our study therefore confirms that group CBT improves psychiatric symptoms in PD patients also when compared with a psychoeducational intervention. The CBT group therapy began with a brief summary of the aims of the group and the rationale for learning what would be taught during the sessions. Each session focused on a specific set of skills. The first level of CBT group therapy consisted of modifying specific thoughts and behaviors.Citation34 This level included identification of thoughts and behaviors with potentially positive or negative effects on mood, and the identification of PD motor symptoms associated with mood and anxiety changes. The second level included learning self-instructional methods, which allowed the patients to start taking over the function previously played by the therapist.Citation35 The third level focused on logical analysis and was based on methods similar to those developed by Ellis,Citation36 and, later, by Beck et al.Citation37 At this level, the patients question the logic of taking certain facts, values or perspectives for granted, and consider alternative ways of interpreting their own experiences.Citation38 Some sessions were aimed at understanding the patients’ vulnerability and their fear of the future.

A further novel finding of our study is the improvement in NMS in patients treated with group CBT. NMS in PD include neuropsychiatric symptoms, autonomic dysfunction, sleep disorders, fatigue, and pain. Among patients with PD, the presence and severity of NMS is associated with poorer quality of life, nevertheless few studies have investigated the effect of specific treatments addressing these disabling symptoms.Citation39 The finding that group CBT improved NMS scores while psychoeducational therapy did not, suggests that group CBT is a useful therapeutic approach which should be considered in the treatment of PD patients. It is important to note that NMS improved in a general way, and improvement was not due only to changes in the scores of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

In this study, we used a group therapy approach to allow patients suffering from the same neurological disorder (ie, PD) to interact with each other in an organized manner on the basis of shared experiences, fears, and expectations. In this framework, the group has a personal experience and evolution, a social space that promotes the development of relations between individuals that belong to the group.Citation40

The therapeutic factors of group therapy are the universality, the acquisition of new information, the infusion of hope and altruism, the enhancement of socialization techniques, imitative behavior, interpersonal learning, group cohesion and the psychological adaptation to the presence of an organic neurological pathology.Citation41 Patients with chronic neurological diseases tend to experience an increased degree of stigma, withdrawal, and social isolation, which play a significant role in both the development and persistence of psychiatric comorbidity.Citation42 The exchange of information, the development of socializing techniques, self-disclosure, shared cognitive analysis of emotions and restructuring techniques create a sense of cohesion and belonging.Citation43–Citation47 The recognition by individuals within the same group of both similarities and differences enhances the development of functions as well as of metacognitive skills. In PD patients, group CBT can provide a particularly powerful sense of universality and cohesion that reduces the sense of stigma and isolation through direct social support,Citation48 whereas, the psychoeducational program in a group setting allows patients to obtain information and share their concerns, with the attention dedicated to other patients creating a climate of shared hope.

In recent years, many studies have shown the effectiveness of psychoeducational programs for treating psychiatric disorders and have demonstrated the superiority of psychoeducational family interventions as compared to standard treatments.Citation49 Psychoeducation is a specific type of therapy that focuses on educating patients about their disorders and ways of coping. This approach has been shown to be effective in the prevention and management of many psychiatric disorders, psychiatric symptoms in medical conditions, and neuropsychiatric disorders.Citation50–Citation52 The psychoeducation model used in our study was based on the psychoeducational model developed by Carkhuff.Citation53 This model has been adapted in order to teach the interpersonal skills of empathy, respect, concreteness, genuineness, self-disclosure, confrontation, for PD patients with psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, structured psychological therapies that combine psychoeducation and CBT are being increasingly used in patients diagnosed with a variety of psychiatric disorders.Citation54 Psychoeducation is a behavioral therapeutic approach which mainly focusses on briefing the patients about their illness, problem-solving training, communication training, and self-assertiveness training. The lack of clinical improvement in our PD patients treated with the psychoeducational intervention suggests that strategies which include cognitive, affective and psychomotor components such as the group CBT intervention are more likely to change complex behavior patterns influencing mood and anxiety symptoms in PD patients than didactic interventions which focus on knowledge and concepts of illness, such as the psychoeducational program. These changes of complex behavior obtained after CBT were indeed associated with an improvement in psychiatric symptoms when compared with psychoeducation.

Limitations

One limitation of the study is that the psychoeducational treatment was not equivalent to the CBT treatment in terms of number and duration of sessions. The self-report nature of the measures used in the psychiatric evaluation is also a limitation together with the relatively small number of patients studied. This report suggests that studies on a larger population with PD are therefore warranted.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight the potential relevance of a CBT group approach for chronic and disabling illnesses such as PD. The fact that group CBT was effective in PD whereas educational intervention was not, suggests that factors intrinsic to CBT therapy, beyond “social support” are at play in improving symptoms in PD. Group CBT should be considered in addition to standard drug therapy for the treatment of mental health symptoms, particularly depression and anxiety.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting, and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AarslandDLarsenJPCumminsJLLaakeKPrevalence and clinical correlates of psychotic symptoms in Parkinson disease: a community-based studyArch Neurol199956559560110328255

- VeazeyCAkiSOCookKFLaiECKunikMEPrevalence and treatment of depression in Parkinson’s diseaseJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci200517331032316179652

- ReijndersJSEhrtUWeberWEAarslandDLeentjensJFA systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord20082318318917987654

- JonesJDMarsiskeMOkunMSBowersDLatent growth-curve analysis reveals that worsening Parkinson’s disease quality of life is driven by depressionNeuropsychology201529460360925365564

- BerardelliIPasquiniMRoselliVBiondiMBerardelliAFabbriniGCognitive behavioral therapy in movement disorders. A reviewMov Disord Clin Pract201522107115

- YangSSajatovicMWalterBPsychosocial interventions for depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s diseaseJ Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol20122511312122689704

- ColeKVaughanFBrief cognitive behavioural therapy for depression associated with Parkinson’s disease: a single case seriesBehav Cogn Psychother20053389102

- DobkinRDAllenLAMenzaMA cognitive-behavioral treatment package for depression in Parkinson’s diseasePsychosomatics200647325926316684945

- FarabaughALocascioJJYapLCognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease and comorbid major depressive disorderPsychosomatics201051212412920332287

- BerardelliIPasquiniMBloiseMCBT group intervention for depression, anxiety and motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: preliminary findingsInt J Cogn Ther2015811120

- BerardelliAWenningGKAntoniniAEFNS/MDS-ES/ENS [corrected] recommendations for the diagnosis of Parkinson’s diseaseEur J Neurology20132011634

- HoehnMMYahrMDParkinsonism: onset, progression, and mortalityNeurology1967174274426067254

- FahnSEltonRUnified Parkinson’s disease rating scaleFahnSMarsdenCDCalneDGoldsteinMRecent Developments in Parkinson’s DiseaseFolorham Park, NJMacmillan Health Care Information1987

- De BoerAGWijkerWSpeelmanJDde HaesJCQuality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease: development of a questionnaireJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry199661170748676165

- ChaudhuriKRPrieto-JurcynskaCNaiduYThe nondeclaration of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease to health care professionals: an international study using the nonmotor symptoms questionnaireMov Disord20102570470920437539

- NasreddineZSPhillipsNABédirianVThe Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairmentJ Am Geriatr Society2005534695699

- DuboisBSlachevskyALitvanIPillonBThe FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedsideNeurology200055111621162611113214

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.)Washington, DCAPA2000

- HamiltonMA rating scale for depressionJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry196023566214399272

- HamiltonMThe assessment of anxiety states by ratingBr J Med Psychol195932505513638508

- OverallJEGorhamDRThe brief psychiatric rating scalePsychol Rep196210799812

- GuyWECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revisedRockville, MDNational Institute of Mental Health1976

- SantangeloGBaronePCuocoSApathy in untreated, de novo patients with Parkinson’s disease: validation study of Apathy Evaluation ScaleJ Neurol2014261122319232825228003

- BielingPJMcCabeREAntonyMMCognitive Behavioural Therapy in GroupsNew YorkGuilford Press2006

- BernardHBurlingameGFloresPScience to Service Task Force, American Group Psychotherapy Association. Clinical practice guidelines for group psychotherapyInt J Group Psychother200858445554218837662

- BeckATCognitive Therapy and the Emotional DisordersNew YorkInternational Universities Press1976

- LeszczMIntroduction to special issue on group psychotherapy for the medically illInt J Group Psychother19984821371419563235

- LeszczMGoodwinPJThe rationale and foundations of group psychotherapy for women with metastatic breast cancerInt J Group Psychother19984822452739563240

- HofmannSGAn Introduction to Modern CBT: Psychological Solutions to Mental Health ProblemsOxford, UKWiley-Blackwell2011

- ButlerACChapmanJEFormanEMBeckATThe empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analysesClin Psychol Rev2006261173116199119

- FeeneyFEganSGassonNTreatment of depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study using group cognitive behavioural therapyClin Psychol2005913138

- OkaiDAskey-JonesSSamuelMTrial of CBT for impulse control behaviors affecting Parkinson patients and their caregiversNeurology201380979279923325911

- TroeungLEganSJGassonNA waitlist-controlled trial of group cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s diseaseBMC Psychiatry2014141924467781

- GabbardGOBeckJSHolmesJOxford Textbook of PsychotherapyOxfordOxford University Press2007

- MeichenbaumDSelf-instructional strategy training: a cognitive prothesis for the agedHuman Dev197417273280

- EllisAReason and Emotion in PsychotherapyOxford, UKLyle Stuart1962

- BeckATRushAJShawBFEmertGCognitive Therapy of DepressionNew YorkGuilford1979

- BurnsDDFeeling Good: The New Mood Therapy Revised and updatedNew YorkPenguin1999

- SchragASauerbierAChaudhuriKRNew clinical trial for non motor manifestations of Parkinson diseaseMov Disord201530111490150426371623

- ChoiYoung-HeeParkKee-HwanTherapeutic factors of cognitive behavioral group treatment for social phobiaJ Korean Med Sci200621233333616614524

- ThornBEKuhajdaMCGroup cognitive therapy for chronic painJ Clin Psychol200662111355136616937348

- LiottiGDisorganized/disoriented attachment in the psychotherapy of the dissociative disordersGoldbergSMuirRKerrJAttachment Theory: Social, Developmental and Clinical PerspectivesHillsdale, NJAnalytic Press1995343363

- SafranJDSegalZVInterpersonal Process in Cognitive TherapyNew YorkBasic Books Softcover edition1996Jason Aronson, Inc

- HusainiBACummingsSKilbourneBGroup therapy for depressed elderly womanInt J Group Psychother200454329531915253507

- AlonsoASwillerHIGroup Therapy in Clinical PracticeWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Press, Inc1992

- OrmontLRThe Group Therapy ExperienceNew YorkSt. Martin’s Press1992

- BeckJSCoping with Depression when you have Parkinson’s DiseaseBala Cynwyd, PAThe Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy and Research2000

- LorentzenSRuudTGroup therapy in public mental health services: approaches, patients and group therapistsJ Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs201421321922523581992

- ConradiHJBosEHKamphuisJHde JongePThe ten-year course of depression in primary care and long-term effects of psychoeducation, psychiatric consultation and cognitive behavioral therapyJ Affect Disord201721717418228411506

- DonkerTGriffithsKMCuijpersPChristensenHPsychoeducation for depression, anxiety and psychological distress: a meta-analysisBMC Med200977920015347

- NusseyCPistrangNMurphyTHow does psychoeducation help? A review of the effects of providing information about Tourette syndrome and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderChild Care Health Dev201339561762723461278

- WisemanHMousaSHowlettSReuberMA multicenter evaluation of a brief manualized psychoeducation intervention for psychogenic non-epileptic seizures delivered by health professionals with limited experience in psychological treatmentEpilepsy Behav201663505627565438

- ColijnSHoencampESnijdersHJAvan der SpekMWADuivennoordenHJA comparison of curative factors in different types of group psychotherapyInt J Group Psychother1991413653781885253

- SwartzHASwansonJPsychotherapy for bipolar disorder in adults: a review of the evidenceFocus201412325126626279641