Abstract

Purpose

Internet-based treatments have been tested for several psychological disorders. However, few studies have directly assessed the acceptability of these self-applied interventions in terms of expectations, satisfaction, treatment preferences, and usability. Moreover, no studies provide this type of data on Internet-based treatment for flying phobia (FP), with or without therapist guidance. The aim of this study was to analyze the acceptability of an Internet-based treatment for FP (NO-FEAR Airlines) that includes exposure scenarios composed of images and real sounds. A secondary aim was to compare patients’ acceptance of two ways of delivering this treatment (with or without therapist guidance).

Patients and methods

The sample included 46 participants from a randomized controlled trial who had received the self-applied intervention with (n = 23) or without (n = 23) therapist guidance. All participants completed an assessment protocol conducted online and by telephone at both pre- and posttreatment.

Results

Results showed good expectations, satisfaction, opinion, and usability, regardless of the presence of therapist guidance, including low aversiveness levels from before to after the intervention. However, participants generally preferred the therapist-supported condition.

Conclusion

NO-FEAR Airlines is a well-accepted Internet-based treatment that can help enhance the application of the exposure technique, improving patient acceptance and access to FP treatment.

Introduction

Internet- and computer-based treatments have been tested and can be considered evidence-based treatments for several psychological disorders.Citation1–Citation4 Specifically, for anxiety disorders (including panic, specific phobias, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder), Internet-based treatments have shown large effect sizes as compared to control groups (waiting list or placebo treatment) and equal or greater effects when compared to face-to-face treatment.Citation5–Citation8

Authors have pointed out that the use of the Internet to deliver psychological treatment can help address common mental health treatment barriers – specifically, in terms of access and geographical reach, versatility, safety, acceptability, and convenience.Citation9–Citation11 Focusing on the specific phobias, Internet-based treatments can help overcome the limitations of in vivo exposure, such as low acceptance by patients and therapists and the difficulties in accessing treatment outlined in several studies.Citation12–Citation14

The implementation of Internet-based interventions is promising, but some challenges remain.Citation15,Citation16 One important issue in research related to self-applied programs is acceptability. Although clinical effectiveness is important, the acceptability of Internet-based treatments is an additional criterion that is likely to affect their implementation.Citation17 Acceptability refers to the degree to which patients (or other users) are satisfied or at ease with a service and willing to use it.Citation7,Citation18 A treatment is acceptable when it is perceived as fair and reasonable, appropriate, and non-intrusive in addressing a problem.Citation17,Citation19 Following the recommendations of the United Kingdom technology appraisal of computerized treatments, evaluation of treatment acceptability must also be a priority.Citation15 In fact, taking an intervention’s acceptability into account can improve adherenceCitation20 and outcomes.Citation21 Some variables related to treatment acceptability are expectations, satisfaction, treatment preferences, and usability.Citation22–Citation24 The literature suggests that “expectations” may be crucial to the psychotherapy process and its outcomes,Citation25 and positive expectations have been associated with better outcomes.Citation26,Citation27 Moreover, “satisfaction” is another important variable because it provides information about the feasibility of the intervention, helping to optimize its effectiveness.Citation26,Citation28 Treatment “preferences” – the systems or interventions that are preferred by patients – are considered a way to enhance clinical utility, thereby increasing treatment adherence and outcomes.Citation29–Citation32

In spite of the importance of treatment acceptability, few studies have focused on its assessment in terms of Internet-based interventions,Citation22–Citation24,Citation33,Citation34 and most of them provide only indirect data.Citation35,Citation36 The most commonly used rating to measure acceptability is program adherence.Citation26,Citation37 Although this information about the completion rate is quite important, it is necessary to evaluate acceptability more directly, as Kaltenthaler et alCitation15 concluded in their systematic review. With regard to “usability” testing, it has been described as a method for evaluating user performance and acceptance of a product during its development process.Citation38 Results from usability studies can help us to enhance the technology developed. However, few studies have assessed usability or ease-of-use issues in Internet- and computer-based interventions.Citation23,Citation39–Citation42 As Currie et alCitation41 claimed research that tests user perceptions of usability in computerized mental health self-help programs is still in its infancy, in spite of their advances and advantages.

Studies on Internet-based treatments for specific phobias are scarce. The literature we reviewed reveal two small trials – one on spider phobiaCitation43 and another on snake phobiaCitation44 – but the authors did not assess treatment acceptance. In a series of cases, Botella et alCitation45 provided preliminary data on the acceptability of a self-applied telepsychology program using an intranet to treat small-animal phobia (spiders, cockroaches, and mice). In addition, Kok et alCitation46 pointed out that an Internet-based exposure intervention with weekly support was well accepted in outpatients awaiting face-to-face psychotherapy for several phobias (including specific phobia), although a high dropout rate was observed (only 13.3% finished the intervention). Furthermore, some interesting studies have been conducted in the area of online image-based exposure for spider fear, providing evidence in support of their efficacy.Citation47 For example, Matthews et alCitation48 found that alternating fear-relevant and -irrelevant exposure (continuous vs intermittent exposure) was feasible in online exposure and may lead to habituation with less summed anxiety that has implications for tolerability and acceptability. However, acceptability was not directly assessed throughout those studies. Recently, Schröder et alCitation49 conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a transdiagnostic Internet intervention for individuals with panic and phobias, and they evaluated satisfaction with the program. Participants reported a moderate level of satisfaction. Furthermore, the authors pointed out that attitudes toward psychological online interventions moderated the effects of the program, as there was a substantial increase in benefits among patients with more positive attitudes.

With regard to flying phobia (FP), some computer-assisted treatments have shown patient acceptance, but the Internet was not used to deliver them.Citation30,Citation50 Tortella-Feliu et alCitation50 carried out a randomized trial comparing three computer-aided exposure treatments for FP: virtual reality exposure treatment assisted by a therapist; computer-aided exposure with a therapist present throughout the exposure sessions; and self-administered computer-aided exposure. All three of the interventions were well accepted without compromising their efficacy. Based on data from Tortella-Feliu et al,Citation50 Bretón-López et alCitation30 pointed out that participants’ preferences for the three interventions differed in terms of subjective effectiveness, recommendation to others, and aversiveness. According to the authors, “facing the flight situation in a more realistic way makes the participants judge the treatment as more aversive.”Citation30 In this regard, decreasing a treatment’s aversiveness is a key feature and an ethical commitment in efforts to improve the application of the exposure technique.Citation12–Citation14 Thus, research on patients’ acceptance of computer-assisted exposure using significant stimuli is especially relevant. Particularly in the case of FP, the application of exposure through interactive computer programs and Internet-based delivery is specifically recommended because it can produce lower aversion levels and reach more people in need.

Another relevant research issue that might be related to the acceptability of Internet-based treatments is the degree of support or guidance provided during the intervention process.Citation51,Citation52 Recently, a growing body of research has been conducted to determine the role of human support in these interventions, and the literature shows the importance of providing this support.Citation53 Meta-analyses have shown that Internet- and computer-based treatments that offer some level of professional support or guidance produce larger effect sizes and lower dropout rates than self-help programs without any support.Citation53,Citation54 Patients generally reported greater satisfaction with therapist-supported Internet-based interventions; however, as explained earlier, patient satisfaction was not formally assessed.Citation6 Other recent studies have found no significant differences in adherence between conditions with and without human support.Citation55,Citation56 Therefore, it is interesting to continue to investigate whether there are differences in acceptability, depending on the support provided.

To our knowledge, no studies have directly assessed these variables to determine the user acceptability of an Internet-based program for FP that includes exposure scenarios composed of images and real sounds. The aim of the present study is to examine the acceptability of NO-FEAR Airlines in terms of expectations, satisfaction, treatment preferences, and usability. A secondary aim is to explore patient acceptance of two ways of delivering the program – with and without therapist guidance.

Patients and methods

Research design

This study employed a randomized control design where the participants were randomly allocated to three groups:Citation57 1) Internet-based exposure treatment for FP without therapist guidance (NO-FEAR Airlines completely self-applied); 2) Internet-based exposure treatment for FP with therapist guidance (brief, weekly call; NO-FEAR Airlines with therapist guidance); and 3) a waiting-list control. In the present study, data from participants allocated to the two treatment conditions were analyzed. The RCT was registered under ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02298478), approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitat Jaume I (Castellón, Spain, December 20, 2014), and conducted in compliance with the study protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki, the CONSORT statements (http://www.consort-statement.org), CONSORT-EHEALTH guidelines,Citation58 and good clinical practice guidelines.

Participants

The final sample included in this study comprised 46 participants (NO-FEAR Airlines completely self-applied, n = 23; NO-FEAR Airlines with therapist guidance, n = 23). Of the total sample, 32 participants were women and 14 were men. The mean age was 37.59 years (SD = 11.13), ranging from 20 to 65 years. Most of the participants had completed a university degree (80.4%) or secondary studies (19.6%). With regard to marital status, 50% were married, 45.7% single, and 4.3% separated or divorced. Most of the sample were employed (58.7%), 17.4% were students, 17.4% were unemployed, and 6.5% were retired. Participants came from Spain (89%), Colombia (4.3%), the USA (2.2%), Cuba (2.2%), and Italy (2.2%). With regard to pharmacological treatment, 93.5% of the participants were not taking any regular medication, and 6.5% of the sample were receiving anxiolytics for anxiety-related symptoms.

Recruitment and procedure

Recruitment was carried out online using both professional websites (ie, LinkedIn) and non-professional social networks (ie, Facebook and twitter), as well as advertisements in newspapers and posters placed in local universities. People who were interested could request participation through the research website (www.fobiavolar.es) and by signing the informed consent form. All participants were contacted by telephone to screen them for the inclusion and exclusion criteria and to explain the research terms. Participants who met the study criteria received a diagnostic telephonic interview, and were randomly assigned to one of the three experimental groups using a computer randomization program (Epidat 4.0) run by an independent researcher who was blinded to the characteristics of the study. Before starting the treatment, participants allocated to the two treatment conditions (completely self-applied or self-applied with therapist guidance) received a brief explanation of the rationale for the treatment, how to use the program, and information of each experimental condition (including details about how both conditions – with and without therapist guidance – work), but information about which condition they would receive was not provided at this stage. Thereafter, participants reported their preferences without knowing the treatment to which they had been assigned. Next, researchers told patients the condition to which they had been randomly allocated, and they assessed their expectations about the treatment. Posttreatment, participants reported their satisfaction, their preferences, and the usability of the program. A detailed description of the recruitment process and procedure is provided in the study protocol.Citation57

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: adults who were 18 years of age or older and met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Health Disorders-Fifth edition (DSM-5)Citation59 criteria for specific, situational phobia (FP); sufficient knowledge to understand and read Spanish; the ability to use a computer; and access to the Internet. Exclusion criteria were: receiving psychological treatment for FP; diagnosis of a severe mental disorder (abuse or dependence on alcohol or other substances, psychotic disorder, dementia, or bipolar disorder); presence of depressive symptomatology, suicidal ideation or plan; presence of heart disease; pregnancy (from the fourth month). Participants with comorbid and related disorders (ie, panic disorder, agoraphobia, claustrophobia, or acrophobia) were included when FP was the primary diagnosis. Receiving pharmacological treatment was not an exclusion criterion during the study period, but any increase and/or change in the medication implied the participant’s exclusion from the study. A decrease in pharmacological treatment was accepted.

Measures

Diagnostic interview

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-TR (ADIS-IV) is a semi-structured interview used to determine the diagnostic status and quantify different features related to the phobia (on a scale from 0 to 8). The section on specific phobias was used in this study. This interview has been validated in Spanish and shows adequate psychometric properties.Citation60–Citation62

Treatment Preferences Questionnaire

The Treatment Preferences Questionnaire was specifically developed for this research.Citation57 This instrument is composed of five questions designed to measure participant preferences for the two treatment conditions included in the study (with and without therapist support): 1) “Preference” (“If you could have chosen between the two treatments, which one would you have chosen?”); 2) “Subjective effectiveness” (“Which of these two treatments do you think would have been the most effective in helping you to overcome your problem?”); 3) “Logic” (Which of these two treatments do you think would have been the most logical to help you overcome your problem); 4) “Subjective aversion” (“Which of these two treatments do you think would have been the most aversive?”); and 5) “Recommendation” (“Which of these two treatments would you recommend to a friend with the same problem you have?”). Questions have two response options based on the two treatment conditions.

Treatment expectations and satisfaction scales

These questionnaires were adapted from Borkovec and NauCitation63 to measure participant expectations before treatment and their later satisfaction with it. Each scale includes six items rated from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“very much”). The questions addressed how logical the treatment seemed, to what extent the patient expected to be satisfied with it, whether the patient would recommend the treatment to others, whether it would be useful in treating other problems, the treatment’s usefulness for the patient’s problem, and to what extent it could be aversive. This adaptation has been used in several studies.Citation22–Citation24,Citation50,Citation64

Qualitative Interview

A Qualitative Interview was also specifically developed to assess participant opinions about the NO-FEAR Airlines program and the support received. This interview included 10 questions: nine of them regarding usefulness of exposure scenarios, fixed pictures, sounds, psychoeducation, overlearning, and the opinion about receiving support or not rated on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 = very little; 2 = little; 3 = something; 4 = a lot; and 5 = very much) and one dichotomous question (“yes” or “no”) regarding whether they would like having at their disposal the program for more time after the treatment has finished. Additionally, options to extend the participants’ qualitative responses were available.

Usability and Acceptability Questionnaire

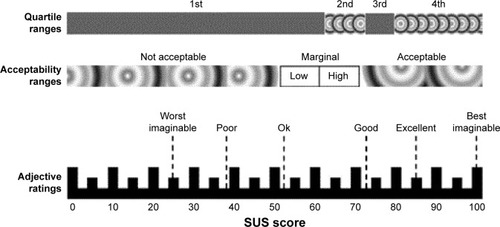

This instrument was adapted from the System Usability Scale (SUS) in order to assess the usability of a service or product and the acceptance of technology by the people who use it.Citation65,Citation66 The SUS has been shown to be a valuable and robust tool for assessing the quality of a wide range of user interfaces, as it is easy to use and understand.Citation23,Citation65 This scale includes 10 statements rated on a five-point scale measuring agreement with the statement (0 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). The final score is obtained by adding the scores on each item and multiplying the result by 2.5. Scores range from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate better usability, according to Bangor et alCitation65,Citation67 (). shows the mapping of the SUS adjective ratings scale (from “Worst imaginable” to “Best imaginable”) corresponding to acceptability ranges (from “Not acceptable” to “Acceptable”), and quartiles range (from the first to fourth quartile). We replaced the word “system” with “NO-FEAR Airlines,” and we adapted some items to assess: learnability, capacity to use, orientation, effectiveness, ecological model, ease of instructions, visibility, intention to use, utility, and ease of use. The Usability and Acceptability Questionnaire is currently being validated by our research group, and a short form consisting of seven items was used in a previous study, showing a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94.Citation40

Treatment program

NO-FEAR Airlines is an Internet-based exposure treatment for FP. This program was designed to be completely self-applied over the Internet, and it allows people who are afraid of flying to be exposed to images and sounds related to their phobic fears on a standard personal computer. From a clinical point of view, NO-FEAR Airlines is based on a previous program – Computer Assisted Fear of Flight Treatment (CAFFT).Citation50,Citation68 NO-FEAR Airlines was designed with linear navigation () – that is, the patient can only continue on to the next section. This design helps to optimize the treatment structure (assessment, psychoeducation, exposure, and overlearning). The graphical user interface includes visual flying metaphors in order to improve immersion and the sense of presence in the exposure scenarios.

The program includes both an “assessment protocol” and a “treatment protocol”. The “treatment protocol” has three therapeutic components: psychoeducation, exposure, and overlearning. “Psychoeducation” consists of information about what the program will contain, as well as specific information related to FP using text, vignettes, and illustrations, in order to make the therapeutic content more attractive to the patient. The “Exposure” component is provided through six scenarios composed of significant stimuli such as images and real sounds related to the flight process: 1) flight preparation; 2) airport; 3) boarding and taking off; 4) the central part of the flight; 5) the airplane’s descent, approach to the runway, and landing; and 6) sequences with images and auditory stimuli related to plane crashes. Exposure presents the different scenarios, depending on the patient’s anxiety level recorded in the assessment (based on the FFQ-II questionnaire scores).Citation69 Therefore, the system reacts in real time to the exposure needs of each patient, organizing the scenes from low to high anxiety. “Overlearning” is offered as additional exposure (to each scenario). Patients can choose the scenarios they want to face based on their needs, with a higher degree of difficulty when storm conditions and turbulence are simulated. The length of the treatment depends on each patient’s pace. Patients were advised to carry out approximately two exposure scenarios per week, taking a few days off between sessions, although each participant was free to advance at his/her own pace within a maximum period of 6 weeks. A detailed description of NO-FEAR Airlines can be found in the published literature.Citation57,Citation70

The program described earlier was delivered in two formats: 1) NO-FEAR Airlines completely self-applied – participants self-administered the Internet-based treatment, and only automatic support was provided by the program; technical assistance (ie, web-accessibility problems or forgotten password) was provided if necessary. 2) NO-FEAR Airlines with therapist guidance – in this case, participants self-applied the treatment over the Internet and received minimal therapist support consisting of a brief weekly phone call (maximum 5 min) to assess and guide the participant’s progress by providing feedback and reinforcement until she/he had finished the treatment. In addition, the therapist checked for any problems and reminded the participant about the recommended treatment pace. Guidance content was standardized, although it could be tailored to patients’ needs. However, support calls had no additional clinical content. Telephonic support was provided by trained and experienced psychologists.

Statistics and data analysis

Sociodemographic and participant data were examined by applying chi-square (χ2) tests for categorical variables and Student’s t-tests for continuous data. Group differences were studied using χ2 tests for participant preference patterns and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) for expectations, satisfaction, usability, and the quantitative statements from the opinion interview. Separate MANOVAs were applied for each of the outcome measures mentioned, where all items were entered into the MANOVA as dependent variables and with the experimental group as a fixed factor (independent variable). In addition, a MANOVA was conducted to analyze whether significant changes were yielded between expectations (at pre-) and satisfaction (at post-intervention). The main effect of time as well as the interaction effect (time by group) were included in the statistical analysis. For the opinion interview, the proportion of participants who rated a score of 4 or 5 for questions on usefulness of exposure scenarios, fixed pictures, sounds, psychoeducation, and overlearning were calculated, and the differences between groups were compared using the χ2 test. Comparisons between the usefulness of the components of exposure scenarios reported by participants were assessed using paired sample t-tests. With regard to the Usability and Acceptability Questionnaire, the proportion of agreement with the statements (participants who rated a score of 3 or 4) was also calculated and χ2 tests to compare differences in proportions between groups were used. Finally, the SUS adjective ratings scale (from “Worst imaginable” to “Best imaginable”) was used to provide a qualitative comparison of usability scores ().Citation65–Citation67 All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.

Results

Sociodemographic and participant data

Sociodemographic and participant data are presented in . No statistical differences were found between conditions (NO-FEAR Airlines completely self-applied vs NO-FEAR Airlines self-applied with therapist guidance) with regard to demographic data and medication-intake patterns.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and participant data

Attrition and adherence

Forty-six participants started the program and completed the pretreatment assessment. From the total sample, 13 participants (28.26%) withdrew from the program: six in the NO-FEAR Airlines completely self-applied condition (13.04%) and seven in the NO-FEAR Airlines self-applied with therapist support condition (15.22%). No significant differences in attrition rates were found between the treatment conditions. Dropout reasons were reported as follows: own illness (N = 1), partner illness (N = 1), exposure scenarios did not evoke anxiety (N = 1), lack of time (N = 1), and unable to contact them (N = 9). At the posttreatment assessment, the data on treatment acceptance were obtained from 33 participants (NO-FEAR Airlines completely self-applied, n = 17; NO-FEAR Airlines self-applied with therapist guidance, n = 16).

Preferences

Results of χ2 tests revealed significant differences between treatment conditions on all preference measures, except “aversiveness” at baseline and posttreatment. Before treatment, most participants (71.7%) preferred the self-applied condition with therapist guidance (χ2 = 8.70; p < 0.01), 87% considered it more effective than the completely self-applied condition (χ2 = 25.13; p < 0.001), 82.6% of participants reported the therapist-supported condition as being more logical (χ2 = 19.57; p < 0.001), and 82.6% of participants would recommend it to a friend who had the same problem (χ2 = 19.57; p < 0.001). In addition, the completely self-applied condition was considered more aversive by 60.9% of participants, although statistically significant differences were not found.

Posttreatment, 72.7% of participants continued to prefer the self-applied treatment with therapist guidance (χ2 = 6.82; p < 0.01), 84.8% considered it more effective (χ2 = 16.03; p < 0.001), 90.9% assessed this condition as more logical (χ2 = 22.09; p < 0.001), and 87.9% would recommend it to a friend who had the same problem (χ2 = 18.95; p < 0.001). With regard to aversiveness, 54.5% of participants chose the completely self-applied program as the most aversive condition (χ2 = 0.273; p = 0.602), but no significant differences were reported between groups.

Expectations and satisfaction

As shows, results from analyzing participant expectations and satisfaction with the Internet-based program revealed high scores on all expectations and satisfaction measures, except “aversiveness” – which obtained low scores. MANOVA analysis did not reveal significant differences between the two ways of delivering the treatment on any of the expectations and satisfaction measures. In addition, results showed a statistically significant reduction between scores at pre- (that refer to expectations) and post-intervention (satisfaction scale; F[6, 26] = 2.875; p < 0.05), specifically for the items that referred to “satisfaction with the intervention” (F[1, 31] = 2.796; p < 0.05) and “usefulness for treating their problem” (F[1, 31] = 5.908; p < 0.05). Nevertheless, no significant interaction effect was found.

Table 2 Expectations and satisfaction scores

Opinion interview

Results from the opinion interview revealed that the “exposure scenarios” were assessed as useful (mean 3.48, SD 0.91). All program components were valued as helpful, and no statistical differences were found between treatment conditions. Specifically, the proportion of participants who rated scores of 4 or 5 (on a scale ranging from 1 “very little” to 5 “very much”) for the question that referred to the usefulness was 69.57% for exposure scenarios, 50% for fixed pictures, 89.13% for sounds, 65.21% for psychoeducation component, and 73.9% for overlearning. No statistically significant differences were found for proportions of participants reporting values of 4 or 5 between both experimental groups.

With regard to the comparison between components of exposure scenarios, the “sounds” of each scenario were considered significantly more useful than the fixed images (p < 0.001), psychoeducation (p < 0.01), and overlearning component (p < 0.001; ). Moreover, fixed images were considered significantly less useful than psychoeducation (p < 0.05) and overlearning components (p < 0.05). Qualitative opinions of some participants pointed out that they would prefer navigable images such as 360° view images or short videos with movement images. In addition, 72.7% of participants would like to have access to the program after completing the treatment for the first time, in order to use it in the future and go over it between flights.

Table 3 Opinion interview

Finally, with regard to the opinion about receiving support or not, participants who received the “weekly therapist guidance” pointed out that they liked it (mean 4.56, SD 0.81) and considered it “useful” (mean 4.25, SD 1.06), expressing a positive opinion ranging from “a lot” and “to very much”. Participants allocated to the completely self-applied condition said they would have liked to receive therapist support and rated it as helpful between “something” and “very much” (mean 3.35, SD 1.45; mean 3.11, SD 1.36, respectively).

Usability and Acceptability

Usability and Acceptability scores are shown in . According to Bangor et al,Citation67 their results revealed that NO-FEAR Airlines showed high acceptability levels among participants, and it was classified as “excellent” on the Usability Adjective Rating Scale (). The MANOVA analysis did not reveal statistical differences between groups (F[10, 22] = 0.986; p = 0.483). The proportion of participants from the total sample who gave a rating of 3 or 4 (on a scale ranging from 0 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree”) is displayed in . Overall, values ranged from 73.91% to 100%. Moreover, χ2 tests did not reveal statistically significant differences on proportion of agreement (on who rated 3 or 4) between both of the experimental groups.

Table 4 Usability and Acceptability Questionnaire

Discussion

The present study aimed to analyze the acceptability of an Internet-based treatment for FP (NO-FEAR Airlines) that includes exposure scenarios composed of images and real sounds. A secondary aim was to compare patient acceptance of two methods of delivering this self-applied treatment (completely self-applied or self-applied with therapist guidance). On the one hand, results for “adherence” showed that most of the participants completed the online intervention (71.24%). Thus, the dropout rate was in line with other studies that used the Internet to deliver psychological treatment (~30%).Citation71–Citation73 Nevertheless, this result contrasts with Kok et al,Citation46 who found a high attrition rate in treatments for phobic outpatients. On the other hand, no differences in adherence were found in the present study when considering therapist guidance. Data on the impact of support on adherence to Internet-based interventions is inconsistent and varies across studies.Citation53–Citation56,Citation74–Citation76

With regard to treatment “preferences” assessed at pre- and post-intervention stages, results indicated that participants generally preferred the self-applied condition with therapist guidance. They considered this treatment condition to be more effective and more logical, and they would recommend it more than the completely self-applied condition, although no differences were found when aversiveness was considered. These results suggest that therapist guidance was not relevant in deciding which condition they would prefer in terms of aversiveness, but it clearly affected patient preferences overall. These findings are congruent with studies that recommend the need to offer support, guidance, and reinforcement to the participant during exposure in self-applied treatments, and this support has been related to patient preferences.Citation30 It is interesting that, in this study, the therapist’s guidance did not include clinical content, which is linked to the important issue of who is providing the support and what kind of guidance is required. Although few studies have been carried out on acceptability variables, the literature suggests that the qualifications of the people providing the guidance (technicians vs clinicians) might not be very important.Citation77 Generally, authors suggest that, depending on the degree of structure of the Internet intervention model adopted, guidance can be mainly practical and supportive – based on reinforcement, rather than explicitly therapeutic content.Citation9 Thus, guidance could be provided through automated reinforcement and persuasive technologies.Citation55,Citation75 This idea agrees with authors who indicate that unguided Internet-based interventions can work similarly with automated guidance and no human support.Citation56,Citation78–Citation81 Therefore, we suggest that including automated guidance and making patients aware of it could help to reduce these differences in preferences for Internet interventions delivered with or without therapist guidance.

In contrast, participants in both groups reported high “expectations” and “satisfaction” scores, including low aversiveness levels toward the Internet-based exposure both before and after the treatment. These results coincide with previous studies showing that computer-assisted treatments are well accepted, in terms of expectations and satisfaction to treat FP.Citation50,Citation68 In addition, they are consistent with studies conducted with Internet-based interventions for specific phobias and other anxiety disorders, where participants also reported positive expectations and high satisfaction.Citation2,Citation22,Citation45,Citation81 It is true that patient satisfaction has generally been found to be higher in therapist-supported, Internet-based interventions.Citation6 However, coinciding with our results, other studies have found that providing therapist support does not affect satisfaction.Citation56,Citation82 In addition, the data on aversiveness are especially relevant. As pointed out earlier, participants in both intervention groups reported low aversiveness levels toward the Internet-based exposure intervention in the evaluation of both expectations and satisfaction. Moreover, no differences were found in treatment preferences related to aversiveness, and the number of participants who preferred the supported intervention diminished after treatment. This is important because reducing aversion is a major challenge in exposure treatment for phobias.Citation12–Citation14 These results suggest that NO-FEAR Airlines – self-applied with and without therapist guidance – could help improve the exposure technique’s acceptance due to its reduced exposure aversiveness. According to Botella et al,Citation22 Internet-delivered treatments may be particularly valuable to patients who are reluctant to start an in vivo exposure intervention because they provide a less frightening way to confront their fears. Moreover, it is interesting to note that scores on satisfaction scale (assessed at posttreatment) were lower than expectations (assessed at pretreatment) on several items, revealing significant reductions for the items that referred to satisfaction with the intervention and usefulness for treating their problem. No significant interaction effect was found, indicating that reductions were similar in both groups. In spite of such significant decrements on satisfaction items, it is worth considering that mean scores were still high, revealing good participant opinion, and the differences found could be caused by the initial high expectations. Additional explanations are twofold: First, participants were volunteers that could be especially interested in receiving an Internet-based treatment, thus inflating expectation scores. Second, participants could have experienced some anxiety levels during the treatment and exposure scenarios that may affect the decrement in satisfaction scores. Thus, anxiety experienced during the treatment may have had an influence on satisfaction reported after treatment. Further research is required to confirm these hypotheses.

With regard to the results obtained from the “opinion interview”, all the program components (ie, psychoeducation, exposure, and overlearning) were accepted and found to be useful by the participants, agreeing with studies using computer-assisted treatment for FP.Citation68 Focusing particularly on the features of exposure scenarios, sounds were rated as more useful than fixed pictures. These data are consistent with previous findings that highlight the critical role of sound in evoking anxiety in patients with FP.Citation50,Citation83 In addition, some participants suggested the inclusion of navigable images, such as 360° pictures, or short videos with movement images in order to improve the scenarios and evoke a greater sense of presence. This issue addresses an interesting question related to improving exposure by creating more realistic exposure scenarios. However, according to Tortella-Feliu et al,Citation50 literature has shown that treatment effects are not enhanced by enriching computer-generated exposure environments or creating more sophisticated immersive conditions.Citation83–Citation85 Moreover, some authors have suggested that, particularly referring to the flight situation, facing the feared situation in a more realistic way may evoke higher aversiveness levels,Citation30 which could hinder the treatment’s acceptability. However, more research is needed on this topic.

Finally, “usability” results would place NO-FEAR Airlines between the third and fourth quartile, achieving the “excellent” rating on the Usability Adjective Rating Scale in both the intervention conditions and showing that receiving therapist guidance did not affect the system’s usability. Based on the technology acceptance model, authors have suggested that one of the factors that can be related to the intention to use a product in the future is ease of use.Citation86–Citation89 Therefore, efforts to research and ensure the usability of Internet-based treatments might lead more people to accept the Internet to treat their psychological problems, continue to use it in the future, and recommend it to friends and family. Thus, an important challenge in psychological treatments is improved – that is, their dissemination.Citation90

In summary, our results showed that NO-FEAR Airlines was well accepted among participants, with no differences when considering therapist guidance, in terms of attrition rates, expectations, satisfaction, opinions, and usability. However, participants preferred the self-applied condition with therapist guidance. Therefore, our results partially agree with studies that highlighted the role of therapist guidance to enhance treatment acceptability.Citation6 According to our findings, we suggest these inconsistencies could point out that the role of therapist guidance has different implications, depending on the disorder involved. Thus, in specific phobias – specifically in FP – therapist guidance might not seem to be relevant in improving treatment acceptability, particularly with regard to attrition rates, expectations, satisfaction, opinion, and usability. A further explanation could be related to the fact that all participants were contacted by a therapist at both the pre- and posttreatment stages to explain the research criteria and design as well as to conduct the subsequent assessments. Studies have found that providing initial human contact enhances the treatment.Citation91 Nevertheless, based on our data, therapist guidance affects treatment preferences. More research is needed to formally assess the acceptability of Internet-based treatments, depending on the support provided.

In conclusion, together, our results highlight good acceptability of NO-FEAR Airlines by patients for the treatment of FP, when completely self-applied and self-applied with therapist guidance. However, the present study presents some limitations that should be mentioned. First, assessments were conducted online and via phone calls. Some authors suggest that psychometric properties may change when the assessment is conducted via the web,Citation92 although several studies have shown the usefulness of Internet- and telephonically administered assessments and their concordance with traditional face-to-face assessment.Citation93–Citation96 Second, another limitation to consider is that participants voluntarily requested online access to the study. Thus, people who wanted to participate might be especially interested in receiving a treatment delivered via the Internet and more likely to accept the program by expressing a favorable opinion. Future research might examine these issues in other contexts (ie, primary care). Another interesting issue that has not been considered in this study refers to the possible influence of the technical support provided, which was available for both experimental conditions. The number of participants receiving technical support by phone was not recorded in our trial; thus, the differences in patterns of use could not be analyzed. Finally, usability assessment was based on one questionnaire rather than on qualitative feedback that might indicate overall program impressions. This could interfere with the interpretation of the usability testing and its subsequent use for program improvement or refinement.Citation41 In the future, qualitative analyses should be included to report detailed and complementary data on program usability and participant opinions.

In sum, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze patient acceptance of an Internet-based program that includes exposure scenarios composed of images and real sounds for the treatment of FP, while comparing two delivery methods – completely self-applied and self-applied with therapist guidance. NO-FEAR Airlines is presented as a well-accepted FP treatment self-applied via the Internet. This program helps to enhance the application of the exposure technique, improving patient acceptance and access to FP treatment. Further research – as, for example, to investigate whether there are sociodemographic variables that may influence the acceptance of these Internet-based programs – is needed. Finally, future research is required to develop increasingly sophisticated Internet-based programs that include different technologies (ie, persuasive technologies and more sophisticated and relevant exposure scenarios) in order to improve acceptance and access to evidence-based psychological interventions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Spain; Plan Nacional I+D+I; grant no PSI2013-41783-R); Red de Excelencia (grant no PSI2014-56303-REDT) PROMOSAM, Research in processes, mechanisms and psychological treatments for mental health promotion from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (2014); a PhD grant from Generalitat Valenciana (VALi+d; grant no ACIF/2014/320); and CIBER (CIBER Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición is an initiative of ISCIII).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AnderssonGInternet-delivered psychological treatmentsAnnu Rev Clin Psychol20161215717926652054

- AndrewsGCuijpersPCraskeMGMcEvoyPTitovNComputer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysisPLoS One2010510e1319620967242

- HedmanELjótssonBLindeforsNCognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost–effectivenessExpert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res201212674576423252357

- SijbrandijMKunovskiICuijpersPEffectiveness of internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysisDepress Anxiety201633978379127322710

- MewtonLSmithJRossouwPAndrewsGCurrent perspectives on Internet delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with anxiety and related disordersPsychol Res Behav Manag20147374624511246

- OlthuisJVWattMCBaileyKHaydenJAStewartSHTherapist-supported Internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adultsCochrane Database Syst Rev20163CD01156526968204

- PeñateWFumeroAA meta-review of Internet computer-based psychological treatments for anxiety disordersJ Telemed Telecare201622131126026188

- RegerMAGahmGAA meta-analysis of the effects of internet- and computer-based cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxietyJ Clin Psychol2009651537519051274

- AnderssonGTitovNAdvantages and limitations of Internet-based interventions for common mental disordersWorld Psychiatry201413141124497236

- AndrewsGNewbyJMWilliamsADInternet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders is here to stayCurr Psychiatry Rep201517153325413639

- PeñateWAbout the effectiveness of telehealth procedures in psychological treatmentsInt J Clin Health Psychol2012123475487

- DeaconBJFarrellNRTherapist barriers to the dissemination of exposure therapyStorchEMcKayDHandbook of Treating Variants and Complications in Anxiety DisordersNew YorkSpringer2013363373

- Garcia-PalaciosABotellaCHoffmanHFabregatSComparing acceptance and refusal rates of virtual reality exposure vs. in vivo exposure by patients with specific phobiasCyberpsychol Behav200710572272417927544

- OlatunjiBODeaconBJAbramowitzJSThe cruelest cure? Ethical issues in the implementation of exposure-based treatmentsCogn Behav Pract2009162172180

- KaltenthalerEBrazierJDe NigrisEComputerised cognitive behaviour therapy for depression and anxiety update: a systematic review and economic evaluationHealth Technol Assess20061033iiixixiv1168

- WhitfieldGWilliamsCIf the evidence is so good–why doesn’t anyone use them? A national survey of the use of computerized cognitive behaviour therapyBehav Cogn Psychother20043215765

- WallinEEMattssonSOlssonEMThe preference for Internet-based psychological interventions by individuals without past or current use of mental health treatment delivered online: a survey study with mixed-methods analysisJMIR Ment Health201632e2527302200

- RushBScottREApproved telehealth outcome indicator guidelines: quality, access, acceptability and costCalgary, AB, CanadaCalgary Health Telematics Unit, University of Calgary2004

- KazdinAEAcceptability of alternative treatments for deviant child behaviorJ Appl Behav Anal19801322592737380752

- SantanaLFontenelleLFA review of studies concerning treatment adherence of patients with anxiety disordersPatient Prefer Adherence2011542743921949606

- SwiftJKCallahanJLThe impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: a meta-analysisJ Clin Psychol200965436838119226606

- BotellaCGallegoMJGarcia-PalaciosABañosRMQueroSAlcañizMThe acceptability of an Internet-based self-help treatment for fear of public speakingBr J Guid Couns2009373297311

- BotellaCMiraAMoragregaIAn Internet-based program for depression using activity and physiological sensors: efficacy, expectations, satisfaction, and ease of useNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20161239340627042067

- BotellaCPérez-AraMÁBretón-LópezJQueroSGarcía-PalaciosABañosRMIn vivo versus augmented reality exposure in the treatment of small animal phobia: a randomized controlled trialPLoS One2016112e014823726886423

- GreenbergRPConstantinoMJBruceNAre patient expectations still relevant for psychotherapy process and outcome?Clin Psychol Rev200626665767815908088

- de GraafLEHuibersMJRiperHGerhardsSAArntzAUse and acceptability of unsupported online computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for depression and associations with clinical outcomeJ Affect Disord2009116322723119167094

- GoossensMEVlaeyenJWHiddingAKole-SnijdersAEversSMTreatment expectancy affects the outcome of cognitive-behavioral interventions in chronic painClin J Pain20052111826 discussion 69–7215599128

- MarksIMCavanaghKGegaLComputer-aided psychotherapy: revolution or bubble?Br J Psychiatry200719147147318055948

- BachofenMNakagawaAMarksIMHome self-assessment and self-treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder using a manual and a computer-conducted telephone interview: replication of a UK-US studyJ Clin Psychiatry199960854554910485637

- Bretón-LópezJTortella-FeliuMdel AmoARPatients’ preferences regarding three computer-based exposure treatments for Fear of FlyingBehav Psychology2015232265285

- García-PalaciosAHoffmanHGSeeSKTsaiABotellaCRedefining therapeutic success with virtual reality exposure therapyCyberpsychol Behav20014334134811710258

- TarrierNLiversidgeTGreggLThe acceptability and preference for the psychological treatment of PTSDBehav Res Ther200644111643165616460671

- Montero-MarínJPrado-AbrilJBotellaCExpectations among patients and health professionals regarding web-based interventions for depression in primary care: a qualitative studyJ Med Internet Res2015173e6725757358

- WoottonBMTitovNDearBFSpenceJKempAThe acceptability of Internet-based treatment and characteristics of an adult sample with obsessive compulsive disorder: an Internet surveyPLoS One201166e2054821673987

- CarrardICrépinCRougetPLamTGolayAVan der LindenMRandomised controlled trial of a guided self-help treatment on the Internet for binge eating disorderBehav Res Ther201149848249121641580

- GunSYTitovNAndrewsGAcceptability of Internet treatment of anxiety and depressionAustralas Psychiatry201119325926421682626

- Kay-LambkinFJBakerALKellyBLewinTJClinician-assisted computerised versus therapist-delivered treatment for depressive and addictive disorders: a randomised controlled trialMed J Aust20111953S44S5021806518

- KushnirukAEvaluation in the design of health information systems: application of approaches emerging from usability engineeringComput Biol Med200232314114911922931

- AndersonPZimandESchmertzSKFerrerMUsability and utility of a computerized cognitive-behavioral self-help program for public speaking anxietyCogn Behav Pract2007142198207

- CastillaDGarcia-PalaciosAMirallesIEffect of Web navigation style in elderly usersComput Hum Behav201655909920

- CurrieSLMcGrathPJDayVDevelopment and usability of an online CBT program for symptoms of moderate depression, anxiety, and stress in post-secondary studentsComput Hum Behav201026614191426

- StjernswärdSOstmanMIlluminating user experience of a website for the relatives of persons with depressionInt J Soc Psychiatry201157437538620233895

- AnderssonGWaaraJJonssonUMalmaeusFCarlbringPOstLGInternet-based self-help versus one-session exposure in the treatment of spider phobia: a randomized controlled trialCogn Behav Ther200938211412020183690

- AnderssonGWaaraJJonssonUMalmaeusFCarlbringPOstLGInternet-based exposure treatment versus one-session exposure treatment of snake phobia: a randomized controlled trialCogn Behav Ther201342428429124245707

- BotellaCQueroSBanosRMTelepsychology and self-help: the treatment of phobias using the internetCyberpsychol Behav200811665966418991528

- KokRNvan StratenABeekmanATCuijpersPShort-term effectiveness of web-based guided self-help for phobic outpatients: randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2014169e22625266929

- MatthewsANaranNKirkbyKCSymbolic online exposure for spider fear: habituation of fear, disgust and physiological arousal and predictors of symptom improvementJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry20154712913725577731

- MatthewsAJWongZHScanlanJDKirkbyKCOnline exposure for spider phobia: continuous versus intermittent exposureBehav Change2011283143155

- SchröderJJelinekLMoritzSA randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic Internet intervention for individuals with panic and phobias – one size fits allJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry201754172427227651

- Tortella-FeliuMBotellaCLlabrésJVirtual reality versus computer-aided exposure treatments for fear of flyingBehav Modif201135133021177516

- GilbodySLittlewoodEHewittCREEACT TeamComputerised cognitive behaviour therapy (cCBT) as treatment for depression in primary care (REEACT trial): large scale pragmatic randomised controlled trialBMJ2015351h562726559241

- JohanssonRAnderssonGInternet-based psychological treatments for depressionExpert Rev Neurother2012127861869 quiz 87022853793

- RichardsDRichardsonTComputer-based psychological treatments for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysisClin Psychol Rev201232432934222466510

- AnderssonGCuijpersPInternet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysisCogn Behav Ther200938419620520183695

- KeldersSMBohlmeijerETPotsWTvan Gemert-PijnenJEComparing human and automated support for depression: fractional factorial randomized controlled trialBehav Res Ther201572728026196078

- MiraABretón-LópezJGarcía-PalaciosAQueroSBañosRMBotellaCAn Internet-based program for depressive symptoms using human and automated support: a randomized controlled trialNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat201713987100628408833

- CamposDBretón-LópezJBotellaCAn Internet-based treatment for flying phobia (NO-FEAR Airlines): study protocol for a randomized controlled trialBMC Psychiatry20161629627544428

- EysenbachGCONSORT-EHEALTH GroupCONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of Web-based and mobile health interventionsJ Med Internet Res2011134e12622209829

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental DisordersWashington, DCElsevier2013

- AntonyMOrsilloSMRoemerLPractitioner’s Guide to Empirically-Based Measures of AnxietyNew YorkKluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers2001

- BrownTABarlowDHDi NardoPAAnxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV): Client Interview ScheduleNew YorkGraywind Publications Inc1994

- Di NardoPABrownTABarlowDHAnxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L)New YorkGraywind PublicationsInc1994

- BorkovecTDNauSDCredibility of analogue therapy rationalesJ Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry197234257260

- QueroSPérez-AraMÁBretón-LópezJGarcía-PalaciosABañosRMBotellaCAcceptability of virtual reality interoceptive exposure for the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobiaBrit J Guid Couns2014422123137

- BangorAKortumPTMillerJTAn empirical evaluation of the system usability scaleInt J Hum-Comput Int2008246574594

- BrookeJSUS: a “quick and dirty” usability scaleJordanPWThomasBWeerdmeesterBAMcClellandILUsability Evaluation in IndustryLondon, UKTaylor & Francis1996189194

- BangorAKortumPMillerJDetermining what individual SUS scores mean: adding an adjective rating scaleJ Usability Stud200943114123

- Tortella-FeliuMBornasXLlabrésJComputer-assisted exposure treatment for flight phobiaInt J Behav Consult Ther200842158171

- BornasXTortella-FeliuMGarcía de la BandaGFullanaMALlabrésJValidación factorial del cuestionario de miedo a volar (QPV) [The factor validity of the fear of flying questionnaire]Anál Modif Conducta199925885907 Spanish [with English abstract]

- QueroSCamposDRiera Del AmoANO-FEAR Airlines: a computer-aided self-help treatment for flying phobiaStud Health Technol Inform201521919720126799907

- MelvilleKMCaseyLMKavanaghDJDropout from Internet-based treatment for psychological disordersBr J Clin Psychol201049Pt 445547119799804

- SpekVCuijpersPNyklícekIRiperHKeyzerJPopVInternet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysisPsychol Med200737331932817112400

- van BallegooijenWCuijpersPvan StratenAAdherence to Internet-based and face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a meta-analysisPLoS One201497e10067425029507

- Hilvert-BruceZRossouwPJWongNSunderlandMAndrewsGAdherence as a determinant of effectiveness of internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depressive disordersBehav Res Ther2012507–846346822659155

- KeldersSMKokRNOssebaardHCVan Gemert-PijnenJEPersuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventionsJ Med Internet Res2012146e15223151820

- MusiatPTarrierNCollateral outcomes in e-mental health: a systematic review of the evidence for added benefits of computerized cognitive behavior therapy interventions for mental healthPsychol Med201444153137315025065947

- BaumeisterHReichlerLMunzingerMLinJThe impact of guidance on Internet-based mental health interventions – a systematic reviewInternet Interv201414205215

- KaryotakiERiperHTwiskJEfficacy of self-guided Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of individual participant dataJAMA Psychiatry201774435135928241179

- LanceeJvan den BoutJSorbiMJvan StratenAMotivational support provided via email improves the effectiveness of internet-delivered self-help treatment for insomnia: a randomized trialBehav Res Ther2013511279780524121097

- TitovNAndrewsGSchwenckeGSolleyKJohnstonLRobinsonEAn RCT comparing effect of two types of support on severity of symptoms for people completing Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for social phobiaAust N Z J Psychiatry20094310920926

- MacGregorADHaywardLPeckDFWilkesPEmpirically grounded clinical interventions clients’ and referrers’ perceptions of computer-guided CBT (FearFighter)Behav Cogn Psychother20093711919364403

- TitovNAndrewsGDaviesMMcIntyreKRobinsonESolleyKInternet treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistancePLoS One201056e1093920544030

- BornasXTortella-FeliuMFullanaMALlabrésJComputer-assisted treatment of flight phobia: a controlled studyPsychother Res2001113259273

- BornasXTortella-FeliuMLlabrésJDo all treatments work for flight phobia? Computer-assisted exposure versus a brief multicomponent non-exposure treatmentPsychother Res2006164150

- MühlbergerAWiedemannGPauliPEfficacy of a one-session virtual reality exposure treatment for fear of flyingPsychother Res200313332333621827246

- CarvalhoMLGuimarãesHFerreiraJBFreitasAIntention to use M-learning: an extension of the technology acceptance model19th International Conference on Recent Advances in Retailing and Consumer Services ScienceJuly 9–12, 2012Vienna, Austria

- DavisFDPerceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technologyMIS Quart1989133319340

- DavisFDBagozziRPWarshawPRExtrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplaceJ Appl Soc Psychol1992221411111132

- HuangTLLiaoSA model of acceptance of augmented-reality interactive technology: the moderating role of cognitive innovativenessElectron Commer Res2015152269295

- KazdinAERabbittSMNovel models for delivering mental health services and reducing the burdens of mental illnessClin Psychol Sci201312170191

- BoettcherJBergerTRennebergBDoes a pre-treatment diagnostic interview affect the outcome of Internet-based self-help for social anxiety disorder? A randomized controlled trialBehav Cogn Psychother201240551352822800984

- BuchananTJohnsonJAGoldbergLRImplementing a five-factor personality inventory for use on the InternetEur J Psychol Assess2005212115127

- CamposDQueroSBretón-LópezJConcordancia entre la evaluación psicológica a través de Internet y la evaluación tradicional aplicada por el terapeuta para la fobia a volar. [Correlation between psychological evaluation through the Internet and traditional evaluation applied by the therapist for flying phobia]Tesis Psicológica20151025267 Spanish [with English abstract]

- CarlbringPBruntSBohmanSInternet vs. paper and pencil administration of questionnaires commonly used in panic/agoraphobia researchComput Hum Behav200723314211434

- HedmanELjótssonBBlomKTelephone versus internet administration of self-report measures of social anxiety, depressive symptoms, and insomnia: psychometric evaluation of a method to reduce the impact of missing dataJ Med Internet Res20131510e22924140566

- HedmanELjótssonBRückCInternet administration of self-report measures commonly used in research on social anxiety disorder: a psychometric evaluationComput Hum Behav2010264736740