Abstract

Postpartum depression (PPD) is common, occurring in 10%–15% of women. Due to concerns about teratogenicity of medications in the suckling infant, the treatment of PPD has often been restricted to psychotherapy. We review here the biological underpinnings to PPD, suggesting a powerful role for the tryptophan catabolites, indoleamine 2,3-dixoygenase, serotonin, and autoimmunity in mediating the consequences of immuno-inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress. It is suggested that the increased inflammatory potential, the decreases in endogenous anti-inflammatory compounds together with decreased omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acids, in the postnatal period cause an inflammatory environment. The latter may result in the utilization of peripheral inflammatory products, especially kynurenine, in driving the central processes producing postnatal depression. The pharmacological treatment of PPD is placed in this context, and recommendations for more refined and safer treatments are made, including the better utilization of the antidepressant, and the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of melatonin.

Keywords:

Introduction

The prevalence of postpartum depression (PPD) is between 10% and 15%, although generally thought to be considerably underreported.Citation1 A prior history of PPD is the major predictive factor for subsequent occurrence.Citation2,Citation3 Other risk factors include antenatal depressive symptoms, prenatal neuroticism, lower social support, lower socioeconomic status, obstetric complications, including preeclampsia, and major life events or stressors during pregnancy.Citation4–Citation6 PPD is often not recognized and if left untreated can have devastating consequences on the maternal–infant bond as well as on infant mental, motor, and emotional development, leading to depression, anxiety and behavioral problems in the offspring.Citation7–Citation9 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) treats PPD as a subcategory of major depressive disorder (MDD), and not as a separate disorder.

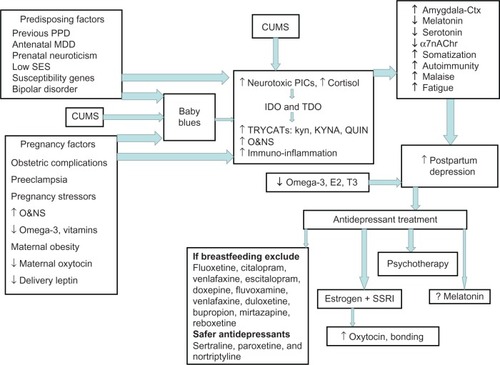

Figure 1 The predisposing, pregnancy and CUMS factors that contribute to PPD, both directly and via “baby blues” induce TDO and IDO, increasing TRYCATs, including KYNA and QUIN, as well as increasing PiCs and O&NS.

Abbreviations: á7nAChr, alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; CUMS, chronic unpredictable mild stress; E2, estradiol; EDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; kyn, kynurenine; KYNA, kynurenic acid; MDD, major depressive disorder; O&NS, oxidative and nitrosative stress; PIC, proinflammatory cytokine; PPD, postpartum depression; QUIN, quinolinic acid; SES, socioeconomic status; SSI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; T3, thyroid hormone; TDO, tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase; TRYCAT, tryptophan catabolite.

Predisposing factors

The susceptibility to depression, including PPD, is the result of epigenetic, genetic, and stress/environment interactions, including in the very early development of the mother herself. Longer-term follow up of PPD offspring at 16 years of age shows that they are four times more likely to be depressed,Citation10 suggesting an inter-generational transfer that increases offspring depression and PPD susceptibility.

During pregnancy, the mother is under high oxidative challenge, and dietary factors that impinge on oxidant status, including a range of vitamins and trace elements, are thought to contribute to the etiology of PPD. Changes in fatty acid composition during pregnancy quickly return to the normal range following parturition However, an increase in the omega-6/3 ratio increases the risk of PPDCitation11,Citation12 Low maternal omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake is suggested to contribute to decreased maternal and fetal health, interacting with the serotonin transporter alleles to contribute to PPD.Citation13

Decreased pregnancy vitamin D associates with many risk factors for PPD, including preeclampsia,Citation14 suggesting that it will indirectly modulate PPD susceptibility. Maternal obesity and excessive weight gain during pregnancy increase PPD riskCitation15 as do alterations in levels of maternal leptin at delivery.Citation16 However, maternal obesity is associated with decreased vitamin D and omega-3 as well as increased preeclampsia, suggesting that many obesity effects may be indirect. Such dietary susceptibility factors alter the regulation of oxidant status and immuno-inflammatory activations.

Within 48 hours of parturition, maternal levels of cortisol, estrogen, progesterone, and neurosteroids fall dramatically, which has been suggested to contribute to PPD,Citation17,Citation18 perhaps paralleling varying depression sensitivity to hormonal changes in menses and menopause. However, other work suggests that hormonal changes are not the major determinant of PPD,Citation19 although a decrease in allopregnanolone is correlated with decreased mood in the “baby blues” period postnatally.Citation20 Depression during pregnancy, often associated with sleep disturbance,Citation21 increases the risk of PPD.Citation22 Of note, the risk factors for depression during pregnancy are very similar to the risk factors for PPDCitation23 suggesting that prenatal and postpartum depression are intimately related.

In the third trimester, plasma oxytocin concentration negatively correlates with the postpartum score on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale,Citation24 leading the authors to suggest that targeting an increase in oxytocin during pregnancy may decrease PPD. Oxytocin has a significant role in preparing the mother for the process of delivery as well as for lactation and maternal behavioral adaptations. Much research in this area is preclinical, but human studies also show a significant role for varying oxytocin levels, in both pregnancy and infant attachment.Citation25,Citation26 This is of importance as maternal behavioral adaptations, including emotional attachment to the newborn, are often challenged in PPD, resulting in offspring with higher levels of insecure attachment, driving subsequent behavioral and mood problems.Citation10 Decreased oxytocin in adults is also linked to increased anxiety and depression.Citation27

To accommodate the placenta and developing fetus, the maternal immuno-inflammatory response in normal pregnancy has to adapt. In part, this is driven by high maternal oxidative challenge during pregnancy and is important in how risk factors increase PPD susceptibility. This overlaps PPD to recent conceptualizations of adult depression as an immuno-inflammatory response to oxidative and nitrosative stress (O&NS), leading to altered tryptophan catabolism, which drives changes in neuronal activity. Here we review how such a psychoneuroimmunological conceptualization of PPD integrates biological data on course and treatment.

Immunological conceptualizations of depression

Recent conceptualizations of depression have emphasized the effects of increased kynurenine (kyn) in the induction of depression. The driving of the precursor tryptophan down the kyn pathway and away from serotonin and melatonin production is crucial to lowering serotonin in MDD. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the serotonin rate-limiting enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) gene are linked to increased depression during pregnancy as well as postnatally.Citation28 Depressive and anxiety symptoms in the early postnatal period are also linked to a rise in the kyn/tryptophan ratio,Citation29 with increases in the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-á in the cerebral spinal fluid at delivery also evident, indicative of elevated central immuno-inflammatory activity.Citation30 However, a decrease in serotonin is not the only driver of a depressed response. As well as active depressant effects arising from tryptophan catabolites (TRYCATs), such as kyn and kynurenic acid (KYNA), a reduction in the effects of melatonin, particularly during pregnancy and the postpartum period when anti oxidant defenses are low will have wider inflammatory and immune consequences.

Increased peripheral kyn will also actively contribute to depression. Sixty percent of central kyn is peripherally derived, being readily transported over the blood–brain barrier, where it is converted to KYNA by astrocytes and to wider kyn pathway products, including the excitotoxic quinolinic acid (QUIN), by microglia. KYNA inhibits the alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (á7nAChr), decreasing glutamate, acetylcholine, and dopamine levels in the cortex, contributing to decreased cortex activity, cognition, and cortex influence in refining affectively driven behaviors.Citation31 In rodents, prenatal and postnatal exposure to kyn results in cognitive deficits in adulthood.Citation32 Proinflammatory cytokine induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) drives the TRYCATs increase. It should be noted that IDO has site-specific effects, being important at the placental interface for the immune tolerance necessary for successful pregnancy, but also producing neuroregulatory products such as KYNA and QUIN. As such, the loss of the anti-inflammatory effects of melatonin will directly contribute to proinflammatory cytokine induction of IDO.

Another major inducer of kyn is tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), which is highly expressed in the liver, but also in astrocytes and some neurons.Citation33 TDO knockout in the rodent central nervous system is anxioloytic, increasing both neurogenesis and serotonin, the latter 20-fold, emphasizing the importance of TDO in the regulation of central serotonin.Citation34 TDO is induced by cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and cortisol, both of which are inhibited by melatonin.Citation35 Maternal cortisol levels double over pregnancy, suggesting that some of the variation in kyn, KYNA, and kyn/tryptophan ratio may be driven by cortisol induction of TDO, and not solely IDO. The loss of placental melatonin in the maternal circulation following parturition may then contribute to the inflammatory, cytokine, and oxidant induction of TDO and IDO that drive decreases in serotonin and increased kyn in the postpartum period.Citation29

The weeks that separate parturition and the emergence of PPD are often stressful, typically incorporating a brief depressive period of “baby blues.” In the animal literature, a series of novel stressors is used to induce depression, framed in the context of chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS). The driver of CUMS is an increase in peripherally derived kyn, leading to increased levels of QUIN in the amygdala and striatum, as well as a trend increase of KYNA in the cortex.Citation36,Citation37 This generally parallels the changes in depression, where heightened amygdale-driven affective processing occurs at the expense of higher order influences on thoughts and behavior. Interestingly, a pattern of decreased orbital frontal cortex negative feedback on amygdala activity heightens and prolongs amygdala activation, increasing the risk of explosive outbursts, evident in about 40% of people with MDD.Citation38 Given the CUMS inhibition of cortex activity, coupled to heightened amygdala activation, it will be interesting to determine the relevance of cortex KYNA and amygdala QUIN to the common fear in PPD of behaving violently to the infant. This could also suggest an important role for variations in the levels of dopamine D1 receptor activity in the paracapsular cells of the intercalated masses, which surround the amygdala and act as a relay for cortex inhibitory feedback.Citation39 Dopamine D1r activation hyperpolarizes the paracapsular cells, preventing cortex inhibitory feedback and prolonging enhanced amygdala activation. Interestingly oxytocin alleles interact with the dopamine response to stress, correlating with measures of anxiety, attachment, and emotional wellbeing in nonpregnant women,Citation40 suggesting an interaction of amygdala oxytocin with stress responses driving depression and associated aggressive impulses.

Increased QUIN in the anterior cingulate is evident in severe depression, an area of the central nervous system linked to emotional processing.Citation41 QUIN is excitatory via the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, being excitotoxic at higher concentrations. QUIN is produced by IDO activation, probably by amygdala and striatal microglia as a consequence of CUMS. On the other hand, the increase in cortex KYNA decreases cortex arousal. As such, any CUMS effects in the immediate weeks after parturition will increase the amygdalae-driven affective regulation at the expense of higher order cognitive influences on cognitive and behavioral outputs. The associations of hormonal and neurosteroid decreases following parturition would then be sensitizing the mother to the effects of postpartum stressors, acting similarly to CUMS, in driving motivated depressive outputs. Repeat stress is known to decrease allopregnanolone,Citation42 an important regulator of IL-1â modulation of oxytocin in pregnancy.Citation43 This is a perspective that emphasizes the importance of the TRYCAT pathways in driving immunological influences on patterned neuronal activity, both centrally and peripherally.Citation31,Citation44

Interestingly, a decrease in tryptophan is associated more with physiosomatic (formerly psychosomatic) symptoms,Citation45 suggesting that the differentiation of somatization and depression may be important to investigate over pregnancy and PPD. We have previously shown that an increase in the kyn/KYNA ratio is specifically associated with somatization, across different DSM-IV categories,Citation46 emphasizing the importance of a more refined understanding of the TRYCAT paths. Changes in nociceptive processing locally and centrally may be relevant in PPD, indicated by the dramatic potentiation of pain reporting following cesarean section in mothers who had a depressive episode during pregnancy.Citation47 High reporting of feelings of infection, malaise, and fatigue in PPD, coupled with altered T-helper (Th)-1 and Th-2 cytokines is suggestive of wider alterations in immune response, which will contribute to the subjective stress and nociceptive intolerance.Citation48

The decrease in leptin at delivery in women with later PPD may also be associated with TRYCAT regulation.Citation16 Leptin inhibits cortisol production and glucocorticoid receptor activation, suggesting that it will inhibit cortisol induction of TDO. The maternal cortisol levels in late pregnancy correlate with the cortisol response to stress at 6 and 8 weeks postpartum,Citation49 indicating a significant role for regulators of pregnancy cortisol response in determining later stress reactivity. Other studies have found no significant effect of pregnancy cortisol as a risk factor for PPD, but have shown wider dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, including changes in pregnancy corticotrophin releasing hormone.Citation50 A caveat to measures of cortisol is the association of abusive experiences in women prone to depression, with subsequent posttraumatic stress showing an attenuated cortisol stress response.Citation51 This may be relevant to the decrease in cortisol in the study by Salel and colleagues,Citation52 where decreased cortisol was associated with severity of PPD. This highlights the wider developmental influences that come to bear in the etiology of depression, including PPD. That said, the interaction of cortisol with leptin is important, with leptin inhibiting the HPA axis and cortisol increasing leptin in healthy individuals.Citation53 Leptin is negatively coupled to the cAMP pathways, decreasing cAMP induction of KYNA and TDO and is a significant immune regulator,Citation54 increasing Th-1 responses.Citation55 Leptin also has prosurvival and protective effects. However, chronically raised leptin leads to leptin resistance, mediated by increased cAMP pathway activity,Citation56 suppressing the effects of leptin. It is unknown whether increased cAMP in leptin resistance contributes to TRYCAT regulation, linking obesity with MDD and PPD.

The placenta also produces leptin; with placental levels being raised 12-fold in preeclampsia. In the pineal gland of some animals, leptin increases levels of norepinephrine-induced 2, arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase, increasing melatonin production.Citation57 As to whether variations in placental leptin and leptin resistance modulate placental melatonin levels requires investigation. Overall, this suggests a potential role for variations in leptin to modulate different facets of the immune processes driving PPD.

Postpartum depression and immuno-inflammatory pathways

A number of immuno-inflammatory changes are associated with the puerperium, correlating to postpartum mood and anxiety. Immune activation in the early puerperium, as indicated by increased IL-6, IL-1 receptor antagonist (RA), and leukemia inhibitory factor receptor, as well as decreased anti-inflammatory Clara cell protein correlates with early postpartum anxiety and depressive symptoms.Citation58,Citation59 Puerperal IL-6 and IL-1RA are further increased in women with a prior history of depression,Citation60 with anxiety and inflammatory responses being more evident in primiparae women versus multiparae.Citation61 Such immuno-inflammatory, mood, and anxiety increases in the early puerperium correlate with decreased tryptophan and an increase in the kyn/tryptophan ratio,Citation29,Citation62 although not all studies show a correlation of decreased tryptophan with early postpartum mood.Citation63 As such, available data suggest an association of immuno-inflammatory and TRYCAT changes with mood in the early postpartum blues period, and require investigation as to whether this is a direct link to PPD itself. The data as available clearly indicate the postnatal period as an inflammatory condition, increasing the risk of depression, especially in women with a predisposition to depression.

Autoimmunity

Autoimmunity is associated with depression including serotonin autoimmunity and thyroid autoimmunityCitation64,Citation65 Elevations in thyroid stimulating hormone, linked to thyroid autoimmunity, have been proposed as a parturition measure predicting later PPD.Citation66 This would link to the decreased thyroid hormone, evident in PPD, where it negatively correlates with PPD severity.Citation52 Serotonin autoimmunity is associated with increased physiosomatic symptoms, including malaise and neurocognitive symptoms, as well as increased serum neopterin and lysozyme, coupled to increased plasma TNF-á and IL-1 in comparison with depressed patients without 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) autoimmunity.Citation64 This emphasizes the importance that immuno-inflammatory pathways have in the onset of 5-HT autoimmunity. Increased bacterial translocation significantly interacts with these inflammatory processes,Citation67 and may be of relevance in parturition, especially following cesarean section. Fatigue is common in PPD,Citation68 which like malaise is associated with autoimmune activity.Citation69 The interaction of 5-HT autoimmunity with somatization driven by alterations in specific TRYCATs and overlapping with CUMS-associated changes post-parturition in PPD requires investigation. Such a perspective better incorporates the known changes and risk factors in PPD and may lead to more refined treatment, as shown in the summary figure.

Treatment

Treatment of PPD has often utilized different forms of psychotherapy, given the concern about pharmacological treatment postpartum on the suckling infant.Citation70 Other treatment approaches are various including preventative exercise,Citation71 acupuncture, massage, morning light exposure, and hypnosis.Citation72 Here we focus on the role of pharmacological treatments and try to place this in the context of immune-inflammatory pathways, including TRYCATs and O&NS.

There is a general lack of methodologically sound randomized, double-blind placebo controlled clinical trials of antidepressant treatments in pregnancy as well as in PPD.Citation73 Two recent reviews of antidepressants and PPD found only nine studies.Citation70,Citation74 Of these, four were randomized, with only two being placebo controlled.Citation75,Citation76 The nonrandomized trials tend to show a stronger benefit of antidepressants. However, this has to be tempered by design weakness. In the better controlled studies, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are superior to placebo,Citation76 but show no significant advantage when combined with psychotherapy versus psychotherapy alone. The Yonkers et al study produced similar results.Citation75

These studies could suggest that psychotherapy would be the more efficacious and safer option. However, a couple of caveats have to be borne in mind. Most of the antidepressant studies in PPD have comprised groups of women with mainly mild to moderate depression. A meta-analysis of the benefits of antidepressants shows that efficacy over placebo increases with severity of depression.Citation77 Secondly, although women generally respond better to SSRIs than men, variations in the levels of estrogen postpartum may be interacting with SSI response,Citation78 with low estrogen levels, as evident in PPD,Citation52 inhibiting SSI efficacy.Citation79

SSRIs are the most widely used antidepressants in PPD. Systematic reviews on antidepressant use postpartum suggest that sertraline, paroxetine, and nortriptyline are associated with only rare adverse effects in infants and are least likely to show detectable amounts in infant serum.Citation80,Citation81 However, detectable amounts of fluoxetine and citalopram have been found in the infant, as with venlafaxine and escitalopram, decreasing their use postpartum.Citation82 Side effects in infants are found mostly with fluoxetine and citalopram.Citation83 The tricyclic doxepine is also not recommended.Citation83,Citation84 Particular caution should be used when the baby is premature, of low birth weight, or currently ill, as all these conditions are linked to a decrease in metabolic capacity. A general lack of data on fluvoxamine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, bupropion, mirtazapine, and reboxetine suggests that they are best avoided, pending further studies. As in adult depression more generally, if a patient has shown a positive response to a particular antidepressant in the past, it should be considered first choice, subsequently taking the above into account.

The use of SSRIs, increasing the availability of serotonin, is relevant to our understanding of depression, as outlined above. Preliminary data show that SNPs in EDO interact with antidepressant efficacy, highlighting the role of the EDO pathway in the depression-modifying effects of SSRIs.Citation85 An increase in EDO and TDO, driving tryptophan down the kyn pathways and away from serotonin, N-aceytlserotonin, and melatonin production, links with serotonin autoimmunity to suggest that a decrease in serotonin is relevant to depression, including PPD. However, it should be emphasized that the induction of kyn, KYNA, and QUIN is not an incidental sideshow, as these TRYCATs are crucial to the etiology and course of depression. As to whether the utilization of adjunctive melatonin, given its anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant effects, would inhibit the O&NS/inflammation driven changes in TRYCATs in PPD requires investigation. The utilization of melatonin in the treatment of PPD is discussed in more detail below.

Generally, antidepressant treatment would only be commenced with caution, starting with a single treatment at the lowest possible dose. This should be preceded by a careful benefits–risk analysis, with emphasis on the issue of breastfeeding. Breastfeeding may have to be discontinued if dosage is high or multiple pharmacological treatments are used.

Combined treatment

A combination of psychotherapy and antidepressants is often more efficacious than either alone in the treatment of adult depression.Citation86 This is increasingly common in urban areas, but sometimes hard to achieve in rural communities. The utilization of telephone, text, and Internet has proved useful in the absence of direct, personal contact psychotherapy and may be an important point of contact for women with PPD,Citation87 including when adjunctive to pharmacotherapy. This requires more investigation.

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial looking at the effects of either sertraline or placebo conjunctive to psychotherapy in the treatment of PPD, there was a trend for additional benefit, but no significant effect of the SSI.Citation88 The Bloch and colleagues study was limited by a small sample size,Citation88 but like the other well controlled studies,Citation75,Citation76 does not provide convincing evidence for the use of SSRIs either in comparison, or adjunctive, to psychotherapy.

Other biological treatments

A decrease in zinc and magnesium has been shown in PPD.Citation89,Citation90 Thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency increases mouse depression, aggression, confusion and memory impairment, which antidepressants suppress.Citation91 In an animal model of PPD, the administration of zinc, magnesium, and thiamine improved depression and anxiety indicants, as well as total antioxidant status,Citation92 leading the authors to propose beneficial effects of such a combination in PPD.

Estrogen has been proposed as an antidepressant, including for use in PPD, where it would increase oxytocin levels.Citation93 SNPs in the estrogen receptor are associated with increased susceptibility to depression.Citation94 As highlighted above, the initial hypogonadism in early PPD,Citation52 followed by significant fluctuations in subsequent months, may significantly interact with the efficacy of SSRIs. The use of combinations of estrogen and SSRIs requires careful investigation. Possible adjunctive use of testosterone has also been proposed. Such hormonal treatment is thought to be more beneficial in women with a history of premenstrual depression.Citation93 However, this may require a delicate balance with progesterone, which can be problematic, especially when indicants of progesterone intolerance are evident. The role for hormonal treatment of PPD requires further investigation, including as to how hormonal modulations interact with TRYCAT pathways, SSRIs, and oxytocin regulation.

Melatonin and melatonergic medications

Recently, we proposed the efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of postpartum psychosis and depression in bipolar women.Citation95 The tapering down of mood-stabilizers around parturition increases the likelihood of mood dysregulation in the immediate postnatal period, which melatonin may help. Bipolar disorder is by far the major risk factor for postpartum psychosis, but is also a risk factor for PPD. A genetic decrease in melatonin is evident in bipolar disorder.Citation96 A melatonin receptor SNP is associated with depression risk generally,Citation97 suggesting that variations in melatonin will contribute to PPD susceptibility. Alterations in melatonin production are evident in depressed pregnant women, as well as in PPD.Citation98

Melatonin is a powerful antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antinociceptive, and increases mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, being generally free of side effects.Citation99 The placenta produces melatonin, with levels increasing over pregnancy as the placenta grows.Citation100 Melatonin has been used successfully with struggling neonates, with beneficial effectsCitation100,Citation101 and has been proposed to mediate the beneficial effects of breastfeeding on infantile colic and sleep improvement.Citation102

There is growing appreciation of melatonin’s antidepressant action, leading to the development of melatonergic-based pharmaceuticals, including agomelatine (a melatonin MT1r and MT2r agonist and serotonin 2Cr antagonist) and ramelteon (MT1/2r agonist). The efficacy of these melatonergic medications is still to be tested in PPD, although melatonin itself may prove a more effective and safer option. Certainly, the dysregulation in the circadian rhythm and sleep pattern that is common in PPD would be improved, contributing to maternal well-being per se.

Complications in pregnancy, including cesarean section, increase the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-á, which inhibits the production of melatonin by the pineal gland for around 2 weeks after parturition.Citation103 Levels of postsurgical infection following cesarean section are about 10% in the UK.Citation104 It is unknown as to whether postsurgery infection would modulate the increased risk of PPD following cesarean section or impact on levels of TNF-á and melatonin production. As to whether melatonin would have particular efficacy after cesarean section in improving maternal mood and decreasing subsequent PPD requires investigation.

Maternal prenatal depression increases pain reporting in women who have had a cesarean section.Citation47 The greater the severity of acute pain following parturition, irrespective of mode of delivery, increases PPD risk.Citation105 As to whether this would have any relevance to increased levels of the kyn/KYNA ratio, which is associated with somatization and differentiates somatization from MDD requires investigation.Citation45,Citation46 For some, an increase in somatization, rather than MDD, in pregnancy and in the period between parturition and PPD may occur, involving distinct changes in TRYCATs, including a relative increase in kyn/KYNA ratio or a general increase in both kyn and KYNA. As outlined above, a relative increase in kyn, will be a peripheral source for a CUMS-mediated alteration in central TRYCATs, including amygdalae-driven affective regulation by QUIN. The antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects of melatonin are likely to safely dampen such peripheral drivers of central affective regulation. Factors modulating the regulation of kyn aminotransferase, which mediates the conversion of kyn to KYNA would also be a treatment target for such peripheral to central communication, given that KYNA, unlike kyn, cannot be transferred over the blood–brain barrier. Likewise, further breakdown into other TRYCATs would modulate levels and ratios of specific kyn products. It is unknown whether melatonin would influence this.

KYNA will modulate the central and peripheral immune system, as well as nociception, via the á7nAChr. Given that agonism at the á7nAChr has antidepressant effects in rodents, when coupled with a subactive dose of SSI,Citation106 suggests that variations in kyn/KYNA ratio, like estrogen, will relevantly modulate SSI efficacy and doses required. This may have some relevance to the data showing the reemergence of cigarette smoking in women with PPD, who had stopped during pregnancy,Citation107 implying a wider and perhaps more direct role of the á7nAChr in the etiology, course, and treatment of PPD. Nicotine/á7nAChr agonists have antinociceptive effects and would compete with KYNA at the á7nAChr, potentiating the effects of SSRIs, whilst allowing KYNA to have continued antinociceptive effects via the direct activation of the GPR35.Citation108 Melatonin increases levels and the cellular responsiveness of the á7nAChr.Citation109

As to whether these biological processes drive the efficacy of blocking blue light in PPD treatment awaits investigation. Blocking blue light when mothers with PPD awake for middle of the night feeding, prevents melatonin suppression, maintains their circadian rhythm, and hastens recovery from PPD.Citation110

Variations in melatonin will also modulate the effects of oxytocin,Citation111,Citation112 which when decreased in the third trimester correlates with PPD symptoms.Citation24 Melatonin sensitizes myometerial cells to oxytocin, facilitating uterine contractions,Citation111 but can also act to inhibit oxytocin release to gonadotropin-releasing hormone.Citation112 Given the role of oxytocin, like melatonin, in the regulation of the amygdala and stress-induced cortisol reactivityCitation113,Citation114 it is likely oxytocin and melatonin will interact in pregnancy and postpartum to modulate the susceptibility to PPD. Such alterations in the cortisol response and amygdala activity are likely to be driven by changes in EDO and TDO, given the effects of stress-induced inflammatory responses and cortisol respectively, on EDO and TDO induction.

Agomelatine is both an anxioloytic and antidepressant.Citation115 Its efficacy in PPD is untested. Ramelteon is likewise untested in PPD.

Conclusion

The etiology of PPD, like MDD, is determined by many factors, including in the early development of the mother. Its course is driven by O&NS and immuno-inflammatory pathways, subsequently regulating TRYCATs, serotonin, and autoimmunity. Its treatment is approached cautiously, with psychotherapy being generally recommended, due to concerns centered on drug transfer during breastfeeding. A better appreciation of its biological underpinnings should lead to a more targeted and safer pharmaceutical intervention. The antidepressant, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant capacities, and proven safety of melatonin are likely to make a significant contribution to the treatment of this disorder, providing better outcomes for both the mother and her child.

Disclosure

The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interests to declare.

References

- GaynesBNGavinNMeltzer-BrodySPerinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomesEvid Rep Technol Assess (Summ)20051191815760246

- HarrisBBiological and hormonal aspects of postpartum depressed moodsBr J Psychiatry199416432882928199780

- LlewellynAMStoweZNNemeroffCBDepression during pregnancy and the puerperiumJ Clin Psychiatry199758Suppl 1526329427874

- HirstKPMoutierCYPostpartum major depressionAm Fam Physician201082892693320949886

- Martin-SantosRGelabertESubiraAIs neuroticism a risk factor for postpartum depression?Psychol Med2012421559156522622082

- HoedjesMBerksDVogelIPostpartum depression after mild and severe preeclampsiaJ Womens Health (Larchmt)201120101535154221815820

- FieldTPostpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: a reviewInfant Behav Dev20103311619962196

- GoodmanSHGotlibIHRisk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmissionPsychol Rev1999106345849010467895

- WalkerMJDavisCAl-SahabBTamimHReported maternal post-partum depression and risk of childhood psychopathologyMatern Child Health J

- PawlbySHayDFSharpDWatersCSO’KeaneVAntenatal depression predicts depression in adolescent offspring: prospective longitudinal community-based studyJ Affect Dis200911323624318602698

- De VrieseSRChristopheABMaesMFatty acid composition of phospholipids and cholesteryl esters in maternal serum in the early puerperiumProstaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids2003a68533133512711250

- De VrieseSRChristopheABMaesMLowered serum n-3 polyun-saturated fatty acid (PUFA) levels predict the occurrence of postpartum depression: further evidence that lowered n-PUFAs are related to major depressionLife Sci200373253181318714561523

- ShapiroGDFraserWDSéguinJREmerging risk factors for post-partum depression: serotonin transporter genotype and omega-3 fatty acid statusCan J Psychiatry2012571170471223149286

- ChristesenHTFalkenbergTLamontRFJørgensenJSThe impact of vitamin D on pregnancy: a systematic reviewActa Obstet Gynecol Scand201291121357136722974137

- MilgromJSkouterisHWorotniukTHenwoodABruceLThe association between ante- and postnatal depressive symptoms and obesity in both mother and child: a systematic review of the literatureWomens Health Issues2012223e319e32822341777

- SkalkidouASylvénSMPapadopoulosFCOlovssonMLarssonASundstrom-PoromaaIRisk of postpartum depression in association with serum leptin and interleukin-6 levels at delivery: A nested case – control study within the UPPSAT cohortPsychoneuroendocrinology2009341329133719427131

- BlochMMeiboomHLorberblattMBluvsteinIAharonovISchreiberSThe effect of sertraline add-on to brief dynamic psychotherapy for the treatment of postpartum depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychiatry201273223524122401479

- PaskovaAJirakRMikesovaMThe role of steroids in the development of post-partum mental disordersBiomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub11122012

- MillerLJPostpartum depressionJAMA2002287676276511851544

- NappiREPetragliaFLuisiSPolattiFFarinaCGenazzaniARSerum allopregnanolone in women with postpartum “blues”Obstet Gynecol2001971778011152912

- D RheimSKBjorvatnBREberhard-GranMInsomnia and depressive symptoms in late pregnancy: a population-based studyBehav Sleep Med201210315216622742434

- SilvaRJansenKSouzaLSociodemographic risk factors of perinatal depression: a cohort study in the public health care systemRev Bras Psiquiatr201234214314822729409

- LancasterCAGoldKJFlynnHAYooHMarcusSMDavisMMRisk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: a systematic reviewAm J Obstet Gynecol2010202151420096252

- SkrundzMBoltenMNastIHellhammerDHMeinlschmidtGPlasma oyxtocin concentration during pregnancy is associated with development of postpartum depressionNeuropsychopharmacology2011361886189321562482

- FeldmanRWellerAZagoory-SharonOLevineAEvidence for a neuroendocrinological foundation of human affiliation: plasma oxytocin levels across pregnancy and the postpartum period predict mother-infant bondingPsychol Sci20071896597017958710

- GordonIZagoory-SharonOLeckmanJFFeldmanROxytocin and the development of parenting in humansBiol Psychiatry20106837738220359699

- OzsoySEselEKulaMSerum oxytocin levels in patients with depression and the effects of gender and antidepressant treatmentPsychiatry Res200916924925219732960

- FaschingPAFaschingbauerFGoeckeTWGenetic variants in the tryptophan hydroxylase 2 gene (TPH2) and depression during and after pregnancyJ Psychiatr Res20124691109111722721547

- MaesMVerkerkRBonaccorsoSOmbeletWBosmansEScharpéSDepressive and anxiety symptoms in the early puerperium are related to increased degradation of tryptophan into kynurenine, a phenomenon which is related to immune activationLife Sci200271161837184812175700

- BoufidouFLambrinoudakiIArgeitisJCSF and plasma cytokines at delivery and postpartum mood disturbancesJ Affect Disord20091151–228729218708264

- AndersonGNeuronal-immune interactions in mediating stress effects in the etiology and course of schizophrenia: role of the amygdala in developmental co-ordinationMed Hypotheses201176546020843610

- PocivavsekAWuHQElmerGIBrunoJ PSchwarczRPre- and postnatal exposure to kynurenine causes cognitive deficits in adulthoodEur J Neurosci201235101605161222515201

- OhiraKHagiharaHToyamaKExpression of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase in mature granule cells of the adult mouse dentate gyrusMol Brain201032620815922

- FunakoshiHKanaiMNakamuraTModulation of tryptophan metabolism, promotion of neurogenesis and alteration of anxiety-related behavior in tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase-deficient miceInt J Tryptophan Res20114718

- RenSCorreiaMAHeme: a regulator of rat hepatic tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenaseArch Biochem Biophys2000377119520310775460

- LaugerayALaunayJMCallebertJSurgetABelzungCBaronePRPeripheral and cerebral metabolic abnormalities of the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway in a murine model of major depressionBehav Brain Res20102101849120153778

- LaugerayALaunayJMCallebertJSurgetABelzungCBaronePREvidence for a key role of the peripheral kynurenine pathway in the modulation of anxiety- and depression-like behaviours in mice: focus on individual differencesPharmacol Biochem Behav20119816116821167857

- HallerJMikicsEHalászJTóthMMechanisms differentiating normal from abnormal aggression: glucocorticoids and serotoninEur J Pharmacol12520055261–38910016280125

- FuxeKJacobsenKXHöistadMThe dopamine D1 receptor-rich main and paracapsular intercalated nerve cell groups of the rat amygdala: relationship to the dopamine innervationNeuroscience2003119373374612809694

- LoveTMEnochMAHodgkinsonCAOxytocin gene polymorphisms influence human dopaminergic function in a sex-dependent mannerBiol Psychiatry201272319820622418012

- SteinerJWalterMGosTSevere depression is associated with increased microglial quinolinic acid in subregions of the anterior cingulate gyrus: evidence for an immune-modulated glutamatergic neurotransmission?J Neuroinflammation201189421831269

- GirdlerSSKlatzkinRNeurosteroids in the context of stress: implications for depressive disordersPharmacol Ther2007116112513917597217

- BruntonPJBalesJRussellJAAllopregnanolone and induction of endogenous opioid inhibition of oxytocin responses to immune stress in pregnant ratsJ Neuroendocrinol201224469070022340139

- AndersonGMaesMBerkMinflammation-related disorders in the tryptophan catabolite (TRYCAT) pathway in depression and somatizationAdv Protein Chem Struct Biol201288274822814705

- MaesMRiefWDiagnostic classifications in depression and somatization should include biomarkers, such as disorders in the tryptophan catabolite (TRYCAT) pathwayPsychiatr Res201219623243249

- AndersonGMaesMBerkMBiological underpinnings of the commonalities in depression, somatization, and chronic fatigue syndromeMed Hypotheses20127875275622445460

- LouHYKongJFThe effects of prenatal maternal depressive symptoms on pain scores in the early postpartum periodJ Obstet Gynaecol201232876476623075351

- GroerM WMorganKImmune, health and endocrine characteristics of depressed postpartum mothersPsychoneuroendocrinology200732213313917207585

- MeinlschmidtGMartinCNeumannIDHeinrichsMMaternal cortisol in late pregnancy and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal reactivity to psychosocial stress postpartum in womenStress201013216317120214437

- YimISGlynnLMDunkel-SchetterCHobelCJChicz-DeMetASandmanCARisk of postpartum depressive symptoms with elevated corticotropin-releasing hormone in human pregnancyArch Gen Psychiatry200966216216919188538

- XiePKranzlerHRPolingJInteraction of FKBP5 with childhood adversity on risk for post-traumatic stress disorderNeuropsychopharmacology20103581684169220393453

- SalelESEl-BaheiWEl-HadidyMAZayedAPredictors of postpartum depression in a sample of Egyptian womenNeuropsychiatric Dis Treat201391524

- NewcomerJWSelkeGMelsonAKGrossJVoglerG PDagogo-JackSDose-dependent cortisol-induced increases in plasma leptin concentration in healthy humansArch Gen Psychiatry19985599510009819068

- LuchowskaEKlocROlajossyBBeta2 adrenergic enhancement of brain kynurenic acid production mediated via cAMP-related protein kinase A signallingProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200933351952919439240

- De RosaVProcacciniCCalìGA key role of leptin in the control of regulatory T cell proliferationImmunity20072624125517307705

- FukudaMWilliamsK WGautronLElmquistJKInduction of leptin resistance by activation of cAMP-Epac signalingCell Metab20111333133921356522

- GuptaBBYanthanLSinghKMIn vitro effects of 5-hydroxytryptophan, indoleamines and leptin on arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AA-NAT) activity in pineal organ of the fish, Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822) during different phases of the breeding cycleIndian J Exp Biol201048878679221341536

- MaesMLinAHOmbeletWImmune activation in the early puerperium is related to postpartum anxiety and depressive symptomsPsychoneuroendocrinology200025212113710674277

- MaesMOmbeletWLibbrechtIIEffects of pregnancy and delivery on serum concentrations of Clara Cell Protein (CC16), an endogenous anticytokine: lower serum CC16 is related to postpartum depressionPsychiatry Res1999872–311712710579545

- MaesMOmbeletWDe JonghRKenisGBosmansEThe inflammatory response following delivery is amplified in women who previously suffered from major depression, suggesting that major depression is accompanied by a sensitization of the inflammatory response systemJ Affect Disord2001631–3859211246084

- MaesMBosmansEOmbeletWIn the puerperium, primiparae exhibit higher levels of anxiety and serum peptidase activity and greater immune responses than multiparaeJ Clin Psychiatry2004651717614744172

- MaesMClaesMSchotteCDisturbances in dexamethasone suppression test and lower availability of L-tryptophan and tyrosine in early puerperium and in women under contraceptive therapyJ Psychosom Res19923621911971560430

- MaesMOmbeletWVerkerkRBosmansEScharpéSEffects of pregnancy and delivery on the availability of plasma tryptophan to the brain: relationships to delivery-induced immune activation and early post-partum anxiety and depressionPsychol Med200131584785811459382

- MaesMRingelKKuberaMBerkMRybakowskiJIncreased autoimmune activity against 5-HT: a key component of depression that is associated with inflammation and activation of cell-mediated immunity, and with severity and staging of depressionJ Affect Disord2012136338639222166399

- DonneMLSettineriSBenvengaSEarly pospartum alexithymia and risk for depression: relationship with serum thyrotropin, free thyroid hormones and thyroid autoantibodiesPsychoneuroendocrinology201237451953322047958

- SylvénSMElenisEMichelakosTThyroid function tests at delivery and risk for postpartum depressive symptomsPsychoneuroendocrinology2013

- MaesMRingelKKuberaMIn myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, increased autoimmune activity against 5-HT is associated with immuno-inflammatory pathways and bacterial translocation In press 2013

- GroërMDavisMCaseyKShortBSmithKGroërSNeuroendocrine and immune relationships in postpartum fatigueMCN Am J Matern Child Nurs200530213313815775810

- MorrisGMaesMA neuro-immune model of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndromeMetab Brain Dis2013

- Di ScaleaTLWisnerKLAntidepressant medication use during breastfeedingClin Obstet Gynecol200952348349719661763

- NascimentoSLSuritaFGCecattiJGPhysical exercise during pregnancy: a systematic reviewCurr Opin Obstet Gynecol201224638739423014142

- SadoMOtaEStickleyAMoriRHypnosis during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period for preventing postnatal depressionCochrane Database Syst Rev20126CD00906222696381

- Hübner-LiebermannBHausnerHWittmannMRecognizing and treating peripartum depressionDtsch Arztebl Int20121092441942422787503

- NgRCHirataCKYeungWHallerEFinleyPRPharmacologic treatment for postpartum depression: a systematic reviewPharmacotherapy201030992894120795848

- YonkersKALinHHowellHBHeathACCohenLSPharmacologic treatment of postpartum women with new-onset major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial with paroxetineJ Clin Psychiatry200869465966518363420

- ApplebyLWarnerRWhittonAFaragherBA controlled study of fluoxetine and cognitive-behavioural counselling in the treatment of postnatal depressionBMJ199731470859329369099116

- FournierJCDeRubeisRJHollonSDAntidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysisJAMA20103031475320051569

- RubinowDRSchmidtPJRocaCAEstrogen-serotonin interactions: implications for affective regulationBiol Psychiatry19984498398509807639

- PaeCUMandelliLKimTSEffectiveness of antidepressant treatments in pre-menopausal versus post-menopausal women: a pilot study on differential effects of sex hormones on antidepressant effectsBiomed Pharmacother200963322823518502089

- FortinguerraFClavennaABonatiMPsychotropic drug use during breast feeding: a review of the evidencePediatrics20091244e547e55619736267

- WeissmanALevyBTHartzAJPooled analysis of antidepressant levels in lactating mothers, breast milk, and nursing infantsAm J Psychiatry2004161161066107815169695

- PayneJLAntidepressant use in the postpartum period: practical considerationAm J Psychiatry200716491329133217728416

- BerleJOSpigsetOAntidepressant use during breastfeedingCurr Womens Health Rev20117283422299006

- DavanzoRCopertinoMDe CuntoAMinenFAmaddeoAAntidepressant drugs and breastfeeding: a review of the literatureBreastfeed Med201162899820958101

- CutlerJARushAJMcMahonFJLajeGCommon genetic variation in the indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase genes and antidepressant treatment outcome in major depressive disorderJ Psychopharmacol201226336036722282879

- ManeetonNThongkamAManeetonBCognitive-behavioral therapy added to fluoxetine in major depressive disorder after 4 weeks of fluoxetine-treatment: 16-week open label studyJ Med Assoc Thai201093333734220420109

- SarkarSGuptaRTelephone vs face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for depressionJAMA2012308111090109122990260

- BlochMSchmidtPJDanaceauMEffects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depressionAm J Psychiatry2000157692493010831472

- WjeikJDudekDSchlegel-ZawadzkaMAntepartum/postpartum depressive symptoms and serum zinc and magnesium levelsPharmacol Rep20065857157616963806

- EbyGAEbyKLRapid recovery from major depression using magnesium treatmentMed Hypotheses20066736237016542786

- NakagawasaiOMurataAAraiYEnhanced head-twitch response to 5-HT-related agonists in thiamineJ Neural Transm20071141003101017372673

- NiksereshtSEtebarySKarimianMNabavizadehFZarrindastMRSadeghipourHRAcute administration of Zn, Mg, and thiamine improves postpartum depression conditions in miceArch Iran Med201215530631122519381

- StuddJ WA guide to the treatment of depression in women by estrogensClimacteric201114663764221878053

- RyanJScaliJCarrièreIEstrogen receptor alpha gene variants and major depressive episodesJ Affect Disord201213631222122622051074

- AndersonGThe role of melatonin in postpartum psychosis and depression associated with bipolar disorderJ Perinat Med201038658558720707614

- EtainBDumaineABellivierFGenetic and functional abnormalities of the melatonin biosynthesis pathway in patients with bipolar disorderHum Mol Genet201221184030403722694957

- GaleckaESzemrajJFlorkowskiASingle nucleotide polymorphisms and mRNA expression for melatonin MT(2) receptor in depressionPsychiatry Res2011189347247421353709

- ParryBLMeliskaCJSorensonDLPlasma melatonin circadian rhythm disturbances during pregnancy and postpartum in depressed women and women with personal or family histories of depressionAm J Psychiatry2008165121551155818829869

- HardelandRCardinaliD PSrinivasanVSpenceDWBrownGMPandi-PerumalSRMelatonin – a pleiotropic, orchestrating regulator moleculeProg Neurobiol20119335038421193011

- LanoixDBeghdadiHLafondJVaillancourtCHuman placental trophoblasts synthesize melatonin and express its receptorsJ Pineal Res2008451506018312298

- GittoEPellegrinoSGittoPBarberiIReiterRJOxidative stress of the newborn in the pre- and postnatal period and the clinical utility of melatoninJ Pineal Res20094612813919054296

- Cohen EnglerAHadashAShehadehNPillarGBreastfeeding may improve nocturnal sleep and reduce infantile colic: potential role of breast milk melatoninEur J Pediatr2012171472973222205210

- PontesGNCardosoECCarneiro-SampaioMMMarkusRPPineal melatonin and the innate immune response: the TNF-alpha increase after cesarean section suppress nocturnal melatonin productionJ Pineal Res20074336537117910605

- WlochCWilsonJLamagniTHarringtonPCharlettASheridanERisk factors for surgical site infection following caesarean section in England: results from a multicentre cohort studyBJOG2012119111324313322857605

- EisenachJCPanPHSmileyRLavand’hommePLandauRHouleTTSeverity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depressionPain20081401879418818022

- AndreasenJTRedrobeJPNielsenEØCombined á7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonism and partial serotonin transporter inhibition produce antidepressant-like effects in the mouse forced swim and tail suspension tests: a comparison of SSR180711 and PNU-282987Pharmacol Biochem Behav2012100362462922108649

- FernandezJ WGrizzellJAWeckerLThe role of estrogen receptor â and nicotinic cholinergic receptors in postpartum depressionProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry201240C19920623063492

- CosiCMannaioniGCozziAG-protein coupled receptor 35 (GPR35) activation and inflammatory pain: Studies on the antinociceptive effects of kynurenic acid and zaprinastNeuropharmacolog y20116012271231

- MarkusR PSilvaCLMFrancoDGBarbosaEMJrFerreiraZSIs modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by melatonin relevant for therapy with cholinergic drugs?Pharmacol Therapeut2010126251262

- BennetSAlpertMKubulinsVHanslerRLUse of modified spectacles and light bulbs to block blue light at night may prevent postpartum depressionMed Hypotheses200973225125319329259

- SharkeyJTCableCOlceseJMelatonin sensitizes human myometrial cells to oxytocin in a protein kinase C alpha/extracellular-signal regulated kinase-dependent mannerJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20109562902290820382690

- JuszczakMBoczek-LeszczykEHypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor activation stimulates oxytocin release from the rat hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system while melatonin inhibits this processBrain Res Bull201081118519019874874

- LabuschagneIPhanKLWoodAOxytocin attenuates amygdala reactivity to fear in generalized social anxiety disorderNeuropsychopharmacology2010352403241320720535

- HeinrichsMBaumgartnerTKirschbaumCEhlertUSocial support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stressBiol Psychiatry2003541389139814675803

- SrinivasanVZakariaROthmanZLauterbachECAcuña-CastroviejoDAgomelatine in depressive disorders: its novel mechanisms of actionJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci201224329030823037643