Abstract

Background

To review empirical studies of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) reported to be associated with the use of medications generally licensed for treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in the pediatric population.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO® databases were searched from origin until June 2011. Studies reporting ADRs from amphetamine derivates, atomoxetine, methylphenidate, and modafinil in children from birth to age 17 were included. Information about ADR reporting rates, age and gender of the child, type, and seriousness of ADRs, setting, study design, ADR assessors, authors, and funding sources were extracted.

Results

The review identified 43 studies reporting ADRs associated with medicines for treatment of ADHD in clinical studies covering approximately 7000 children, the majority of 6- to 12-year-old boys, and particularly in the United States of America (USA). The most frequently reported ADRs were decrease in appetite, gastrointestinal pain, and headache. There were wide variations in reported ADR occurrence between studies of similar design, setting, included population, and type of medication. Reported ADRs were primarily assessed by the children/their parents, and very few ADRs were rated as being serious. A large number of children dropped out of studies due to serious ADRs, and therefore, the actual number of serious ADRs from use of psychostimulants is probably higher. A large number of studies were conducted by the same groups of authors and sponsored by the pharmaceutical companies manufacturing the respective medications.

Conclusion

Reported ADRs from use of psychostimulants in children were found in clinical trials of short duration. Since ADHD medications are prescribed for long-term treatment, there is a need for long-term safety studies. The pharmaceutical companies should make all information about ADRs reported for these medications accessible to the public, and further studies are needed on the impact of the link between researchers and the manufacturers of the respective products.

Introduction

Psychostimulants, such as amphetamine derivates, methylphenidate, and modafinil, as well as the nonstimulant medication atomoxetine, are considered first-line medication treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in the pediatric population.Citation1 Case reports on serious cardiovascular adverse drug reactions (ADRs), sudden death, and psychiatric disorders led regulatory agencies to warn against the use of methylphenidate in the pediatric population in 2006 and 2007.Citation2,Citation3 In 2006, warnings were also linked to atomoxetine use due to reports of hepatotoxicity and suicidal thoughts in children.Citation4 Concern has been raised about ADRs from long-term treatment with ADHD medications, such as psychosis, sensitization, dependency, and withdrawal reactions.Citation1 The issue of appropriate warnings about possible ADRs to the use of methylphenidate and other ADHD medications is ever more important as usage continues to increase rapidly in many countries: an increase in the number of treated patients has been observed, as well as an increase in the average dispensed daily dose of psychostimulants.Citation5

The use of psychostimulants, particularly methylphenidate, to treat ADHD symptoms in children has increased rapidly since the 1990s. Studies have shown that the prevalence of psychostimulant use in children in the Netherlands increased eight times from 1996 to 2006,Citation6 and in Germany, prescription rates of methylphenidate increased by 96% from 2000 to 2007.Citation7 From 1994 to 2004, the prevalence of psychostimulant use in Norwegian children increased five times,Citation8 while the prevalence of stimulant medication increased ten times in American children from 1987 to 1996.Citation9 Previous meta-analyses and reviews that evaluated the short-term efficacy of psychostimulants on ADHD symptoms in children concluded that psychostimulants are more effective than placebo with respect to treating disturbed attention and impulsivity.Citation1,Citation10 Several articles have reported information about the safety of methylphenidate and other psycho-stimulants in clinical studies,Citation11 but to the current reviewers’ knowledge no articles have systematically reviewed the occurrence of ADRs following the use of ADHD medications in the pediatric population.

The objective of this study is to review published empirical studies on the occurrence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with the use of medications generally licensed for treatment of ADHD symptoms in the pediatric population.

Methods

Literature search

A literature search was performed in PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO® (whole databases without language restriction) using the search terms “atomoxetine” (ATC group N06BA09), “methylphenidate” (ATC group N06BA04), “modafinil” (ATC group N06BA07), “amphetamine” (ATC group N06BA02), “psychostimulants,” and “nonstimulants” combined with any of the following: “adverse drug reaction,” “side effect,” and “adverse event.” Reference lists of identified articles were also screened for additional potentially relevant articles. For further details of the search strategy, please see Appendix 1. Literature searches were updated until September 2011.

Study selection

Using article titles as the selection basis, the first author retrieved and screened the abstracts to identify studies relevant to the study objective. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved in full text and screened for inclusion. To be considered relevant for this review, articles had to be peer reviewed and report ADRs in children in the age group 0–17 years of age associated with the use of psychostimulants.

Psychostimulants were specified as amphetamine derivates, methylphenidate, and modafinil, and nonstimulants as atomoxetine. Articles reporting ADRs from psychostimulants in mixed populations of children and adults were excluded if age-related ADR occurrence was not specified. Articles were excluded if they did not report data on ADR occurrence that made it possible to calculate rates. Hence, case reports, letters, commentaries, interim analyses, meta-analyses, and review articles were excluded. Further, articles reporting unintended events not classified as ADRs and articles on misuse were excluded, although reference lists of these studies were searched for relevant studies.

Data extraction

Data from included articles were extracted using a standard form, one for each article. The following information was recorded: authors, publication year, country, study design, dosage, comparator, monitoring period (weeks), size of study population, age and gender of included population, and ADR reporting rates in percentage. ADR reporting rates were indicated as reported in the original papers. In placebo-controlled studies, information about ADR reporting rates for placebo was also extracted. Information about who had assessed the ADRs, reported ADRs classified as being serious by the respective authors, and funding sources were also recorded. The first author extracted data, while the second author controlled and verified all cases.

Results

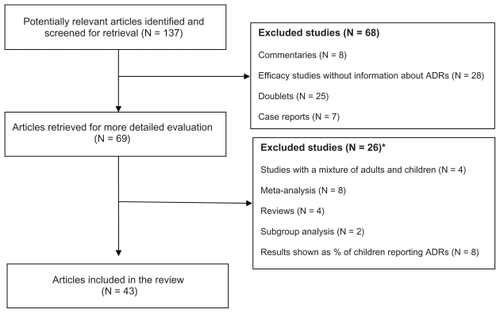

A total of 137 potentially relevant references were identified during the database searches and reference screenings. An overview of the review process and reasons for exclusion are displayed in . Sixty-eight studies were excluded after screening abstracts. Sixty-nine studies were retrieved for full text review. Of these studies, four were later excluded as they reported mixed data on children and adults that could not be separated. Eight meta-analyses and four reviews of efficacy were excluded as they reported information from studies already included. Also excluded were two studies reporting data from a subgroup analysis of already included studies, and nine studies reporting ADRs as percent of children reporting an ADR.

Figure 1 Decision tree of the review process.

Abbreviation: ADRs, adverse drug reactions.

Eventually 43 articles reporting ADRs from psycho-stimulants in the pediatric population were included. displays an overview of the study characteristics of included articles. The majority of studies were conducted in the United States of America (USA), the remaining in Australia, Canada, Europe, Iran, and Latin America. Atomoxetine studies were published in the period from 2001 to 2009; amphetamine studies from 1997 to 2007; methylphenidate studies from 1997 to 2009; and modafinil studies from 2005 to 2009.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies by country, design, study population, and funding

Design and setting

Information about ADRs was reported in clinical studies using different designs, ie, randomized parallel group studies (N = 28);Citation12–Citation15,Citation17–Citation19,Citation22,Citation23,Citation28,Citation31,Citation32,Citation34–Citation36,Citation40,Citation42–Citation47,Citation48–Citation54 randomized crossover studies (N = 6);Citation16,Citation23,Citation25,Citation27,Citation30,Citation39 and open-label designs (N = 9).Citation20,Citation26,Citation29,Citation33,Citation37,Citation38,Citation41,Citation50 The majority of studies were conducted in naturalistic settings at home and at school (N = 38);Citation12,Citation13,Citation15–Citation22,Citation24,Citation26,Citation28–Citation30,Citation31–Citation43,Citation44–Citation54 five articles reported ADRs from children participating in laboratory school protocols,Citation14,Citation23,Citation25,Citation27,Citation30 in which classroom sessions were organized in cycles to include 12 hours of observation. This design consisted of daily schedules of alternating classroom, meals/snacks, recess, and research activities scheduled at specific times during the day. The largest number of studies (N = 21)Citation31–Citation47 concerned atomoxetine; followed by methylphenidate (N = 14;Citation17–Citation30 modafinil (N = 7);Citation48–Citation54 and amphetamine (N = 5).Citation12–Citation16

Dosage and comparator

The tested dosages varied from 10 to 70 mg/day in amphetamine studies; from 5 to 72 mg/day in methylphenidate studies; from 10 to 90 mg/day in atomoxetine studies; and from 100 to 425 mg/day in modafinil studies. Placebo was used as a comparator drug in the majority of studies (N = 28), while an active comparator, was administered in nine studies. Seven open-label studies did not include a control group.

Treatment period

Treatment duration varied from 1 to 32 weeks across studies. Treatment duration varied from 2 to 4 weeks in amphetamine studies; from 1 to 10 weeks in methylphenidate studies; from 3 to 32 weeks in atomoxetine studies; and from 4 to 9 weeks in modafinil studies.

Population

A total of 8512 children were included in the clinical studies, of which 7244 children completed treatment: amphetamine (1076); methylphenidate (2092); atomoxetine (3127); and modafinil (949). The reasons for noncompletion were many, but lack of efficacy and the appearance of ADRs were the most common. The ages of the included children varied from 4 to 17 years (median 6–12 years), and the share of male patients in the studies varied from 0 to 100% (median 69%).

Type of assessor

Parents rated information about ADRs in 20 studies,Citation12–Citation15,Citation19,Citation25–Citation28, Citation32,Citation35–Citation36,Citation40–Citation46,Citation48,Citation50,Citation52 54 patients in 15 studies,Citation18,Citation20–Citation24,Citation31,Citation33–Citation35,Citation38–Citation39,Citation42,Citation44,Citation47 and a combination of teacher/parent (five studies),Citation16–Citation17,Citation30,Citation48–Citation49 and patient/parent (three studies).Citation27,Citation49,Citation51 The articles specified only limited information about applied ADR scales and the classification systems used.

Funding source

In almost all studies the funding source was the manufacturer of the respective medications, and only four studies were publicly funded. Additionally, a large number of the studies were conducted by the same groups of authors who declared conflicts of interest. The majority of the authors received contributions from the pharmaceutical companies producing the medications in return for activities, such as providing scientific advice and making oral and poster presentations at scientific meetings.

ADRs by type and occurrence

– display the ADR reporting rates listed in the included studies for each type of psychostimulant. ADRs of similar type and wording were aggregated in a common category in order to clarify data presentation. The aggregated categories were: weight changes (changes in weight, weight decreased, weight increased, decrease in weight); gastrointestinal pain (abdominal pain, upper abdominal pain, gastrointestinal pain); anxiety (anxiety, anxiousness); influenza (influenza, flu syndrome); tics (tics, motor tics, facial tics); blood pressure changes (diastolic blood pressure, changes in blood pressure); sleeping problems (awake during the night, difficulty falling asleep, sleep disturbance, delayed onset of sleep); changes in heart rate (racing heart, changes in heart rate). Thirty-one categories of ADRs were reported for amphetamine derivates (); 65 categories for methylphenidate formulations (); 55 categories for atomoxetine (); and 38 categories for modafinil (). The following ADRs were most frequently reported for all four psychostimulants: decrease in appetite, gastrointestinal pain, and headache.

Table 2 Adverse drug reaction reporting rates (%) for amphetamine derivates by category and study

Table 3 Adverse drug reaction reporting rates (%) for methylphendiate by category and study

Table 4 Adverse drug reaction reporting rates (%) for atomoxetine by category and study

Table 5 Adverse drug reaction reporting rates (%) for modafinil by category and study

ADRs by seriousness

The majority of reported ADRs were categorized by the authors/investigators as nonserious. shows information about the categories of serious ADRs reported in the clinical studies. Serious cases included aggression (amphetamine, methylphenidate);Citation16 anxiety (amphetamine);Citation16 emotional disturbances (amphetamine);Citation14,Citation15 insomnia (amphetamine, modafinil);Citation13,Citation15,Citation37 and attempted suicide (amphetamine).Citation13

Table 6 Serious ADRs reported for ADHD medications in identified studies

Discussion

This is the first study to systematically review the empirical literature on the occurrence of ADRs reported for ADHD medications in the pediatric population. Information about ADRs from psychostimulants and the nonstimulant atomoxetine was reported in clinical studies of short duration, primarily conducted in 6- to 12-year-old boys, and particularly in the USA. The most frequently reported ADRs were decrease in appetite, gastrointestinal pain, and headache. A large number of studies were conducted by the same groups of authors and sponsored by the pharmaceutical companies manufacturing the respective medications.

Design and setting

Although the review process found a large number of small clinical trials exploring the efficacy of ADHD medications in the pediatic population, only a minor share of these studies reported information about ADRs. The studies included in this article were similar in design and setting, treatment duration, as well as number, age, and gender of included patients. The reliability of the studies may be questioned as the number of reported ADRs varied widely for identical and similar study designs. Further exploration of these questions would require access to the original study material. Large variations in ADR reporting rates were observed between studies and therapeutic groups, and similar types of ADRs were reported for the individual ADHD medications. It is puzzling that large numbers of specific ADRs are reported in some studies, but few if any in others. These findings question the relevance of the many small clinical trials conducted on the medications, particularly atomoxetine and methylphenidate, as they are not designed to measure long-term efficacy and safety.Citation55 Almost all of these clinical trials were sponsored by the pharmaceutical companies producing the subject medications, and therefore, the current reviewers encourage these companies to make information about the ADRs reported in said clinical trials accessible to the public.

Seriousness of reported ADRs

Only a small number of serious ADRs were reported. However, in several of the included studies a large number of children withdrew due to experiencing ADRs, and therefore, the actual number of serious ADRs occurring from the use of ADHD medications might be higher, and some types of ADRs may not have been reported. Information about ADR incidence in the monitored population was only reported if the incidence was above 2% and/or 5%; consequently, information about rarely occurring ADRs is not included. Another issue is that information about definitions and scales to define and evaluate events occurring during the clinical trials is not reported in the articles, thus making it impossible to react to this information. Therefore, the regulatory agencies are encouraged to allow access to the original clinical protocols, so that all information reported for ADHD medications can be made public. A previous study has shown that there are large discrepancies between the data reported in clinical trial protocols and data published in scientific journals.Citation56

Long-term safety aspects of psychostimulant use

Psychostimulants and other ADHD medications are prescribed for long-term treatment in large populations and there is a need for long-term efficacy and safety studies.Citation1 The lack of sufficient knowledge about ADRs at the point of licensing of new medicines makes spontaneous ADR reporting an important source of information about medicine safety.Citation57 As clinical trials in the pediatric population are limited, clinicians and health authorities must rely on spontaneous reports as the main source of information about previously unknown ADRs.Citation57 However, the current review did not find any studies about ADRs from the use of psychostimulants reported to any national ADR databases. Systematic analyses of ADRs reported to national databases are necessary, as these databases constitute a critical (and underestimated) source of important data, especially information about new, serious, and rarely occurring ADRs. Further studies of data from large databases, ie, the World Health Organization/Uppsala Monitoring Centre VigiBase™ (Uppsala, Sweden) or the European Medicines Agency EudraVigilance (London, United Kingdom [UK]) databases, are recommended in order to increase knowledge about ADRs from the use of ADHD medications.

Strengths and limitations of this review

The included studies were conducted over a period of approximately 20 years in different countries, with a great deal of inconsistency in observing and classifying the type and seriousness of reported ADRs. Information about the seriousness of the reported ADRs was extracted from the included studies, and it was not possible for the review to evaluate these ratings, nor to estimate ADRs in terms of effect sizes, as the review did not have access to the original data material. A major limitation of this study is that it is unknown to what extent the causality of these ADRs can be confirmed, and this has implications for the interpretation of the findings in the review. A large number of published clinical studies were not included in this review because these articles did not report information about ADRs, despite the fact that pharmaceutical companies had a legal obligation to monitor ADRs in clinical trials, and therefore, these data must exist. As the clinical trials were mainly sponsored by the pharmaceutical companies that produce the medications, these companies are urged to make these data accessible to the public.

Conclusion

Reported ADRs from the use of psychostimulants in the pediatric population were generally found in clinical trials of short duration. Since ADHD medications are prescribed for long-term treatment there is a need for long-term safety studies. Considering the widespread and increasing use of these medications in children, greater care must be taken when prescribing these medications for long-term use. Further studies of spontaneous reports submitted to national and international databases are recommended in order to increase knowledge about ADRs from the use of psychostimulants in the pediatric population. Pharmaceutical companies should make all information about ADRs reported for ADHD medications accessible to the public. Additionally, the impact of the link between researchers and the manufacturers of the medications needs to be studied.

Authors’ contributions

LA and EHH designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the final draft of the manuscript. LA conducted the literature search and data extraction. EHH checked all data extractions. Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ditte Sloth-Lisbjerg, MSc (Pharm.), for assistance with parts of the literature search and data extraction.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- American Academy of PediatricsClinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderPediatrics200110841033104411581465

- European Medicines AgencyMeeting Highlights From the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, Doc. Ref. EMEA/431407/2007LondonEuropean Medicines Agency2007 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Press_release/2009/12/WC500017068.pdf16–1972007Accessed October 31, 2011

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, United States Food and Drug AdministrationRitalin®, Ritalin-SR®East Hanover, New JerseyNovartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation2007 Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/010187s069,018029s040,021284s011lbl.pdfAccessed October 31, 2011

- MosholderADOverview of ADHD and its pharmacotherapyGaithersburg, MDUnited States Food and Drug Administration, Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee292006 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/slides/2006-4202S1_01_FDA-mosholder.pptAccessed July 18, 2011

- NuttDJFoneKAshersonPEvidence-based guidelines for management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents and in adults: recommendations from the British Association for PsychopharmacologyJ Psychopharmacol2007211104117092962

- TripAMVisserSTKalverdijkLJLarge increase of the use of psycho-stimulants among youth in The Netherlands between 1996 and 2006Br J Clin Pharmacol200967446646819371321

- SchubertIKösterILehmkuhlGThe changing prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and methylphenidate prescriptions: a study of data from a random sample of insurees of the AOK Health Insurance Company in the German State of Hesse, 2000–2007Dtsch Arztebl Int20101073661562120948775

- AsheimHNilsenKBJohansenKForskvivning av sentralstimulerende legemidler ved AD/HD i Nordland [Prescribing of stimulants for ADHD in Nordland County]Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen200712723602362 Article in Norwegian17895938

- ZuvekasSHVitielloBNorquistGSRecent trends in the stimulant medication use among US childrenAm J Psychiatry2006163457958516585430

- BlochMHPanzaKELanderos-WeisenbergerAMeta-analysis: treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with comorbid tic disordersJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200948988489319625978

- AagaardLThirstrupSHansenEHOpening the white boxes: the licensing documentation of efficacy and safety of psychotropic medicines for childrenPharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf200918540141119326364

- BiedermanJKrishnanSZhangYEfficacy and tolerability of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (NRP-104) in children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder: a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, forced-dose, parallel-group studyClin Ther200729345046317577466

- SpencerTJAbikoffHBConnorDFEfficacy and safety of mixed amphetamine salts extended release (Adderall XR) in the management of oppositional defiant disorder with or without comorbid attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children and adolescents: a 4-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, forced-dose-escalation studyClin Ther20062840241816750455

- WigalSBMcGoughJJMcCrackenA laboratory school comparison of mixed amphetamine salts extended release (Adderall XR) and atomoxetine (Strattera) in school-aged children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Atten Disord20059127528916371674

- BiedermanJLopezFABoellnerSWA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of SLI381 (Adderall XR) in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderPediatrics2002110225826612165576

- EfronDJarmanFBarkerMSide effects of methylphenidate and dexamphetamine in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a double-blind, crossover trialPediatrics199710046626669310521

- ArabgolFPanaghiLHebraniPReboxetine versus methylphenidate in treatment of children and adolescents with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorderEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry2009181535918563471

- FindlingRLBuksteinOGMelmedRDA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of methylphenidate transdermal system in pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200869114915918312050

- NewcornJHKratochvilCJAllenAJAtomoxetine and osmotically released methylphenidate for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: acute comparison and differential responseAm J Psychiatry2008165672173018281409

- MaayanLPaykinaNFriedJThe open-label treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 4- and 5-year-old children with beaded methylphenidateJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200919214715319374023

- FindlingRQuinnDHatchSJComparison of the clinical efficacy of twice-daily Ritalin and once-daily Equasym XL with placebo in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200615845045916791541

- GreenhillLLMunizRBallRREfficacy and safety of dexmethylphenidate extended-release capsules in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200645781782316832318

- McGoughJJWigalSBAbikoffHA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, laboratory classroom assessment of methylphenidate transdermal system in children with ADHDJ Atten Disord20069347648516481664

- GauSSShenHYSoongWTAn open-label, randomized, active-controlled equivalent trial of osmotic release oral system methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in TaiwanJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200616444145516958569

- SilvaRRMunizRPestreichLEfficacy and duration of effect of extended-release dexmethylphenidate versus placebo in school-children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol2006163293251

- KemnerJEStarrHLCicconePEOutcomes of OROS methylphenidate compared with atomoxetine in children with ADHD: a multicenter, randomized prospective studyAdv Ther200522549851216418159

- SwansonJMWigalSBWigalTA comparison of once-daily extended-release methylphenidate formulations in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the laboratory school (the Comacs Study)Pediatrics20041133 Pt 1e206e21614993578

- BiedermanJQuinnDWeissMEfficacy and safety of Ritalin LA, a new, once daily, extended-release dosage form of methylphenidate, in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorderPaediatr Drugs200351283384114658924

- KratochvilCJHeiligensteinJHDittmannRAtomoxetine and methylphenidate treatment in children with ADHD: a prospective, randomized, open-label trialJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200241777678412108801

- PelhamWEGnagyEMBurrows-MacleanLOnce-a-day Concerta methylphenidate versus three-times-daily methylphenidate in laboratory and natural settingsPediatrics20011076e10511389303

- SvanborgPThernlundGGustafssonPAEfficacy and safety if atomoxetine as add-on to psychoeducation in the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in stimulant-naïve Swedish children and adolescentsEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200918424024919156355

- BlockSLKelseyDCouryDOnce-daily atomoxetine for treating pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: comparison of morning and evening dosingClin Pediatr (Phila)200948772373319420182

- TamayoJMPumariegaARotheEMLatino versus Caucasian response to atomoxetine in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol2008181445318294088

- BangsMEEmslieGJAtomoxetine ADHD and Comorbid MDD Study GroupEfficacy and safety of atomoxetine in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and major depressionJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200717440742017822337

- GellerDDonnellyCLopezFAtomoxetine treatment for pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with comorbid anxiety disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry20074691119112717712235

- GauSFHuangYSSoongWTA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial on once-daily atomoxetine hydrochloride in Taiwanese children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200717444746117822340

- KratochvilCJVaughanBSMayfield-JorgensenMLA pilot study of atomoxetine in young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200717217518517489712

- PrasadSHarpinVPooleLA multi-centre, randomized, open-label study of atomoxetine compared with standard current therapy in UK children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)Curr Med Res Opin200723237939417288692

- ArnoldLEAmanMGCookAMAtomoxetine for hyperactivity in autism spectrum disorders: placebo-controlled crossover pilot trialJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200645101196120517003665

- NewcornJHMichelsonDKratochvilCJLow-dose atomoxetine for maintenance treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderPediatrics20061186e1701e170617101710

- EscobarRSoutulloCSan SebastiánJAtomoxetine safety and efficacy in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): initial phase of 10-week treatment in a relapse prevention study with a Spanish sampleActas Esp Psiquiatr20043312632 Article in Spanish15704028

- AllenAJKurlanRMGilbertDLAtomoxetine treatment in children and adolescents with ADHD and comorbid tic disordersNeurology200565121941194916380617

- KelseyDKSumnerCRCasatCDOnce-daily atomoxetine treatment for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, including an assessment of evening and morning behavior: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trialPediatrics20041141e1e815231966

- BiedermanJHeiligensteinJHFariesDEEfficacy of atomoxetine versus placebo in school-aged girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderPediatrics20021106e7512456942

- MichelsonDAllenAJBusnerJOnce-daily atomoxetine treatment for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled studyAm J Psychiatry2002159111896190112411225

- SpencerTHeiligensteinJHBiedermanJResults from 2 proof-of-concept, placebo-controlled studies of atomoxetine in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200263121140114712523874

- MichelsonDFariesDWernickeJAtomoxetine in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response studyPediatrics20011085e8311694667

- KahbaziMGhoreishiARahiminejadFA randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled trial of modafinil in children and adolescents with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorderPsychiatry Res2009168323423719439364

- AmiriSMohammadiMRMohamaddiMModafinil as treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in children and adolescents: a double blind, randomized clinical trialProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry200832114514917765380

- BoellnerSEarlCQAroraSModafinil in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a preliminary 8-week, open-label studyCurr Med Res Opin200622122457246517257460

- WigalSBBiedermanJSwansonJMEfficacy and safety of modafinil film-coated tablets in children and adolescents with or without prior stimulant treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: pooled analysis of 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studiesPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry20068635236017245457

- BiedermanJSwansonJMWigalSBA comparison of once-daily and divided doses of modafinil in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychiatry200667572773516841622

- GreenhillLLBiedermanJBoellnerSWA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of modafinil film-coated tablets in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200645550351116601402

- BiedermanJSwansonJMWigalSBEfficacy and safety of modafinil film-coated tablets in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, flexible-dose studyPediatrics20051166e777e78416322134

- HansenEHTechnology assessment in a user perspective – experiences with drug technologyInt J Technol Assess Health Care1992811501651601585

- GøtzschePHróbjartssonAJohansenHKConstraints on publication rights in industry-initiated clinical trialsJAMA2006295141645164616609085

- AagaardLHansenEHInformation about ADRs explored by pharmacovigilance approaches: a qualitative review of studies on antibiotics, SSRIs, and NSAIDsBMC Clin Pharmacol20099419254390

Appendix 1

Search strategy: complete databases were searched until February 2011

Appendix 2

Excluded studies listed by reason for exclusion, alphabetically by first author: Meta-analyses

- BangsMETauscher-WisniewskiSPolzerJMeta- analysis of suicide-related behavior events in patients treated with atomoxetineJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200847220921818176331 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- GreenhillLLNewcornJHGaoHEffect of two different methods of initiating atomoxetine on the adverse event profile of atomoxetineJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200746556657217450047 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- KratochvilCJWilensTEGreenhillLLEffects of long-term atomoxetine treatment for young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200645891992716865034 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- KratochvilCJMichelsonDNewcornJHHigh-dose atomoxetine treatment of ADHD in youths with limited response to standard dosesJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry20074691128113717712236 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- KratochvilCJMiltonDRVaughanBSAcute atomoxetine treatment of younger and older children with ADHD: a meta-analysis of tolerability and efficacyChild Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health2008212518793405 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- PolzerJBangsMEZhangSMeta-analysis of aggression or hostility events in randomized, controlled clinical trials of atomoxetine for ADHDBiol Psychiatry200761571371916996485 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- SchachterHMPhamBKingJHow efficacious and safe is short-acting methylphenidate for the treatment of attention-deficit disorder in children and adolescents? A meta- analysisCMAJ2001165111475148811762571 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}--><!--${/if:}--> <!--${ifNot: isGetFTREnabled}--><!--${/ifNot:}--><!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}--><!--${/if:}-->PubMed Web of Science ®<!--${googleScholarLinkReplacer: %00empty%00 journal How+efficacious+and+safe+is+short-acting+methylphenidate+for+the+treatment+of+attention-deficit+disorder+in+children+and+adolescents%3F+A+meta-+analysis author%3DHM+Schachter%26author%3DB+Pham%26author%3DJ+King 2001 SchachterHMPhamBKingJHow+efficacious+and+safe+is+short-acting+methylphenidate+for+the+treatment+of+attention-deficit+disorder+in+children+and+adolescents%3F+A+meta-+analysisCMAJ2001165111475148811762571 1475-1488 CMAJ 165 11 %00empty%00 11762571 %00null%00 getFTREnabled FULL_TEXT %00empty%00}--><!--${sfxLinkReplacer: e_1_3_5_2_2_8_1 %00empty%00 url_ver%3DZ39.88-2004%26rft.genre%3Darticle%26rfr_id%3Dinfo%3Asid%2Fliteratum%253Atandf%26rft.aulast%3DSchachter%26rft.aufirst%3DHM%26rft.atitle%3DHow%2520efficacious%2520and%2520safe%2520is%2520short-acting%2520methylphenidate%2520for%2520the%2520treatment%2520of%2520attention-deficit%2520disorder%2520in%2520children%2520and%2520adolescents%253F%2520A%2520meta-%2520analysis%26rft.jtitle%3DCMAJ%26rft.date%3D2001%26rft.volume%3D165%26rft.issue%3D11%26rft.spage%3D1475%26rft.epage%3D1488%26rft_id%3Dinfo%3Apmid%2F11762571 %00empty%00}-->

- WilensTENewcornJHKratochvilCJLong-term atomoxetine treatment in adolescents with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorderJ Pediatr2006149111211916860138 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

Review articles

- BramsMMoonEPucciMDuration of effect of oral long-acting stimulant medications for ADHD throughout the dayCurr Med Res Opin20102681809182520491612 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- FindlingRLEvolution of the treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in children: a reviewClin Ther200830594295718555941 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- MerkelRLJrKuchibhatlaASafety of stimulant treatment in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Part IExpert Opinion Drug Saf200986655668 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- WernickeJFFariesDGirodDCardiovascular effects of atomoxetine in children, adolescents, and adultsDrug Saf2003261072974012862507 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

Studies with a mixture of adults and children/ adolescents

- BangsMEJinLZhangSHepatic events associated with atomoxetine treatment for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorderDrug Saf200831434535418366245 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- MaiaCRMatteBCLudwigHTSwitching from methylphenidate immediate release to MPH-SODAS in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry200817313314217846812 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- PatersonRDouglasCHallmayerJA randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of dexamphetamine in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorderAust N Z J Psychiatry199933449450210483843 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- WernickeJFHoldridgeKCJinLSeizure risk in patients with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder treated with atomoxetineDev Med Child Neurol200749749850217593120 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

Sub-group analyses of clinical studies

- DurellTMPumariegaAJRotheEMEffects of open-label atomoxetine on African-American and Caucasian pediatric outpatients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderAnn Clin Psychiatry2009211263719239830 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}--><!--${/if:}--> <!--${ifNot: isGetFTREnabled}--><!--${/ifNot:}--><!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}--><!--${/if:}-->PubMed Web of Science ®<!--${googleScholarLinkReplacer: %00empty%00 journal Effects+of+open-label+atomoxetine+on+African-American+and+Caucasian+pediatric+outpatients+with+attention-deficit%2Fhyperactivity+disorder author%3DTM+Durell%26author%3DAJ+Pumariega%26author%3DEM+Rothe 2009 DurellTMPumariegaAJRotheEMEffects+of+open-label+atomoxetine+on+African-American+and+Caucasian+pediatric+outpatients+with+attention-deficit%2Fhyperactivity+disorderAnn+Clin+Psychiatry2009211263719239830 26-37 Ann+Clin+Psychiatry 21 1 %00empty%00 19239830 %00null%00 getFTREnabled FULL_TEXT %00empty%00}--><!--${sfxLinkReplacer: e_1_3_5_2_5_2_1 %00empty%00 url_ver%3DZ39.88-2004%26rft.genre%3Darticle%26rfr_id%3Dinfo%3Asid%2Fliteratum%253Atandf%26rft.aulast%3DDurell%26rft.aufirst%3DTM%26rft.atitle%3DEffects%2520of%2520open-label%2520atomoxetine%2520on%2520African-American%2520and%2520Caucasian%2520pediatric%2520outpatients%2520with%2520attention-deficit%252Fhyperactivity%2520disorder%26rft.jtitle%3DAnn%2520Clin%2520Psychiatry%26rft.date%3D2009%26rft.volume%3D21%26rft.issue%3D1%26rft.spage%3D26%26rft.epage%3D37%26rft_id%3Dinfo%3Apmid%2F19239830 %00empty%00}-->

- SpencerTJSalleeFRGilbertDLAtomoxetine treatment of ADHD in children with comorbid Tourette syndromeJ Atten Disord200811447048117934184 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

ADRs presented as number of children reporting ADRs, assessment of rate not possible

- Davari-AshtianiRShahrbabakiMERazjouyanKBuspirone versus methylphenidate in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a double-blind and randomized trialChild Psychiatry Hum Dev201041864164820517641 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- BarkleyRAMcMurrayMBEdelbrockCSSide effects of methylphenidate in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systemic, placebo-controlled evaluationPediatrics19908621841922196520 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- FirestonePMustenLMPistermanSShort-term side effects of stimulant medication are increased in preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled studyJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol19988113259639076 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- PelhamWEGnagyEMChronisAMA comparison of morning-only and morning/late afternoon Adderall to morning-only, twice-daily, and three times-daily methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderPediatrics199910461300131110585981 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- PelhamWEJrGreensladeKEVodde-HamiltonMRelative efficacy of long-acting stimulants on children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder: a comparison of standard methylphenidate, sustained-release methylphendiate, sustained-release dextroamphetamine and pemolinePediatrics19908622262372196522 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- PelhamWEAronoffHRMidlamJKA comparison of Ritalin and Adderall: efficacy and time-course in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorderPediatrics19991034e4310103335 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- RuginoTACopleyTCEffects of modafinil in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an open-label studyJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200140223023511211372 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->

- SwansonJMGreenhillLLLopezFAModafinil filmcoated tablets in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study followed by abrupt discontinuationJ Clin Psychiatry200667113714716426100 <!--${if: isGetFTREnabled}-->