Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most frequent neurological diseases. Despite the modern imaging and nuclear techniques which help to diagnose it in a very early stage and lead to a better discrimination of similar diseases, PD has remained a clinical diagnosis. The increasing number of available treatment options makes the disease management often complicated even when the presence of PD seems undoubted. In addition, nonmotor symptoms and side effects of some therapies constitute some pitfalls already in the preclinical state or at the beginnings of the disease, especially with the progressive effect on patients. Therefore, this review aimed to summarize study results and depict recommended medical treatments for the most common motor and nonmotor symptoms in PD. Additionally, emerging new therapeutic options such as continuous pump therapies, eg, with apomorphine or parenteral levodopa, or the implantation of electrodes for deep brain stimulation were also considered.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder, initially characterized by a loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra that spreads over the course of the disease to almost the whole central nervous system. But although the first description of the “shaking palsy” by James Parkinson was published almost 200 years ago, there is still a lack of understanding of the causes of PD. However, great insight into the pathomechanisms was gained during the last decades, identifying in microscopic postmortem studies ubiquitous Lewy bodies as histological correlates of cell death.Citation1

Nevertheless, PD remains a clinical diagnosis with cardinal motor symptoms such as akinesia, rigidity, and tremor. Yet, advances in different imaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging or nuclear imaging techniques, provide supplementary information allowing a precise distinction from differential diagnosis, such as essential tremor or other parkinsonian syndromes.Citation2,Citation3 Additionally, they allow a classification of subtypes, allowing a more accurate and even earlier diagnosis.Citation4,Citation5 This is crucial for avoiding a delayed therapy for evolving symptoms and therefore improving quality of life (QOL). Also, it could offer in the near future the possibility of designing and studying disease modifying drugs able to slow neurodegeneration, and tailoring patient-specific therapy strategies. One possible way might be the development of alternative and more invasive options that have emerged recently, such as pump therapies or deep brain stimulation (DBS). All these treatments have shown promising results in terms of reducing motor symptoms (tremor, akinesia, and/or rigidity).

Nonmotor symptoms have also gained importance, as patients report them impairing their daily life. For physicians, however, they appear at times difficult to treat and even to identify, as they often intermingle with comorbidities. In this respect, many results have been published lately concerning different medical agents and their efficacy and possibilities, but also their restrictions in PD management. Therefore, this review aims to summarize current recommendations and therapeutic strategies for PD patients.

Nonpharmacologic therapies

From clinical experience and by what patients report, exercise, physical therapy, and speech and/or occupational therapy have a sustainable effect for PD patients in terms of maintaining the status quo and improving QOL. For this purpose, there are numerous offered approaches; yet, listing all of them would certainly go beyond the scope of this work. Still, only a few methods have been tested in high-standard studies and constitute effective therapies.

Methods considered helpful include multiple forms of physical exercise such as tai chi or LSVT BIG™ (LVST Global, Inc, Tucson, AZ, USA) but also speech therapy with the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment.Citation6–Citation11 Nevertheless, they can hardly be considered a replacement of pharmaceuticals, but rather a basis which has to be extended by medical treatment. Particularly, patients suffering from axial signs such as freezing of gait, camptocormia, or severe gait and speech problems do benefit from regular physical and/or speech therapy, and attention can be drawn to movement strategy training or cueing. All other PD patients should also receive regular physical and/or speech therapy and should be motivated to regular exercise. In agreement with other authors, well-designed trials are needed to demonstrate efficient but also cost-effective approaches for nonpharmacological therapies in PD.Citation12

Medical treatment of PD

Therapy should be started as soon as the diagnosis of PD is made. A delayed start of the treatment cannot be justified with the risk of motor fluctuations and one has to keep in mind that patients show the best results when treated early. In addition, the authors believe that the mere attendance of a professional is a consequence of a decreased QOL and therefore an indication for therapy. However, the numerous available possibilities make the best choice difficult for the different indications.

Disease modification

One of the foci in recent PD research has addressed pathomechanisms in an early state for hampering disease progression. This deceleration of the progress in PD has been demonstrated in animal models with selegiline,Citation13 rasagiline,Citation14 pramipexole,Citation15 and coenzyme Q10.Citation16 To date, however, few results were reproducible in humans. Thus, 1 mg rasagiline daily over 18 months possibly delays clinical progression in early stages of PD.Citation17 This is why it is still considered – despite being inconclusive with prior studiesCitation18 – a good choice for younger patients with only mild symptoms. These patients not only benefit from the possible disease modification but also from the improvement in motor symptoms. When rasagiline is not sufficient, it can also be safely combined with other agents, eg, dopamine agonists (DA). In contrast, studies investigating the latter ones alone (eg, pramipexole)Citation19 did not show conclusive neuroprotective properties and can therefore not be recommended for this purpose.

Further insight into disease modification and current investigation can be found in the review by Hart et al.Citation20 The properties of rasagiline as a possibly disease modifying drug can be found in .

Table 1 Possible disease modifying agents in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease

Management of motor symptoms (eg, akinesia, rigidity, and tremor)

Dopaminergic medication

Levodopa

Levodopa in combination with a peripheral decarboxylase inhibitor is still the most effective medication available.Citation18,Citation21 Oral application of levodopa is available in different galenic formulations. The wide range of possibilities allows a selective choice if either fast delivery is needed (eg, in the morning) or long-lasting effects are desired (eg, during the night). Alternatively, “on” phases might be prolonged when using combinations such as catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors with levodopa.Citation22–Citation24 However, patients treated with levodopa tend to develop motor complications after 4–6 years.Citation25

Complications after long-term levodopa treatment involve medically refractory fluctuations and/or dyskinesias. Therefore, the primary use of levodopa should only be considered when there is a lack of efficiency with DAs or side effects impede sufficient symptom control in younger patients with agents other than levodopa. In contrast, levodopa is recommended in older patients as monotherapy or in combination with other drugs even as the first-line option, as it shows high efficacy and good safety.Citation26

DAs

This group of pharmaceuticals comprises medications that activate the dopaminergic receptor with an individual affinity to the distinct subtypes of it (pharmacokinetic properties and details can be found in Kvernmo et al).Citation27 In general, there are two different groups: (1) ergoline and (2) nonergoline derivates. The former are not recommended as first-line medications anymore since they can produce several severe side effects which may cause a considerable risk if they are not specially monitored.Citation28 The nonergoline DA, in contrast, are considered efficacious and safe and are therefore especially recommended for treatment in younger patients in combination with levodopa or as a monotherapy.Citation28 Therefore, a wide range of agents and galenic formulations allows individual therapy, providing constant levels of medication and, eventually, good motor control. In addition, motor complications due to long-term treatment are not as likely as with levodopa therapy and can even be reduced by treatment with DA.Citation29–Citation31 Nevertheless, it should be noted that DAs have a worse short-term risk profile compared to levodopa, causing more psychiatric and nonmotor side effects and making regular follow-up necessary.

Other drugs

Besides levodopa and DAs, there are other medications which have proven efficacious for treatment of motor symptoms in PD.Citation28 These drugs improve the plasmatic levels of levodopa and/or dopamine (monoamine oxidase B [MAOB] inhibitors or COMT inhibitors). Due to their distinct mechanisms, however, each of these substances has advantages and properties that need to be considered. COMT inhibitors, for instance, have no intrinsic effect but increase plasmatic levels of levodopa. It has been proven efficacious for adjunct therapy with levodopa and for the treatment of motor fluctuations.Citation28 Still, there are side effects to be considered, especially tolcapone leading to hepatotoxicity.Citation32 Therefore, entacapone – particularly combined with levodopa – is widely applied in clinical practice, improving activities of daily living and reducing the “off” timeCitation23 in fluctuating patients.Citation33 Similar characteristics can be found for MAOB inhibitors as they also provide higher levels of dopamine, decelerating its metabolization. Hence, it is effective as monotherapy for motor symptoms and also as an adjunct to levodopa.Citation28 Additionally, both available medications (selegiline and rasagiline) are recommended due to their good safety. Taken together, the symptoms of PD might also be positively influenced, targeting the metabolization of dopamine.

On the other hand, neurotransmitters other than dopamine have also shown efficacy for the treatment of PD. Amantadine, for instance, possibly works by antagonizing N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors. However, the role is not clear and interference with other neurotransmitters is also feasible. Despite its unclear mechanism of action, it is recommended for therapy of motor symptoms in young patientsCitation28 and appears to be useful in decreasing levodopa-induced dyskinesias.Citation34,Citation35 Other target structures, eg, the adenosine receptor, are currently under investigation and show promising results.Citation36–Citation38 This should motivate the expansion of ongoing basic research in order to discover further ways for symptomatic treatments for PD.

A summary of the recommended treatment of motor symptoms in PD with the distinct pharmaceuticals can be found in .

Table 2 Management of motor impairments in Parkinson’s disease

Management of special motor symptoms

Dyskinesias and fluctuations

The underlying pathogenesis of dyskinesias and fluctuations is probably the iatrogenic discontinuous administration of dopamine, which is in contrast to the physiologic steady concentrations.Citation39 As a consequence, dyskinesias and fluctuations often emerge due to early and longstanding levodopa therapy. Thus, the best treatment is the delay of levodopa in favor of DA or drugs with other target structures.

If, however, fluctuations occur, a practical approach is to reduce levodopa intervals and keep the dosage constant or to increase it only slightly, being aware that additional medications often lead to compliance problems. Furthermore, expansion of medical treatment can also be recommended. In particular, DA, MAOB inhibitors,Citation40 and amantadineCitation41 demonstrated good efficacy and COMT inhibitors (eg, combined with levodopa) provide more stable plasmatic levels and are therefore a good option. On the contrary, side effects such as the worsening of nonmotor symptoms or the emergence of hallucinations in generally older patients have to be kept in mind. Eventually, therapy options such as pump therapies or the implantation of electrodes for DBS should be contemplated as they are often very efficacious (see below), providing regular and therefore more physiologic dopaminergic stimulation.

Tremor

Tremor as a cardinal symptom in PD mainly manifests as resting or reemerging tremor during holding tasks and might be effectively addressed by classic antiparkinsonian agents in many cases. First-line medications include levodopa or DAs, which show good efficacy. A subgroup of PD patients, on the other hand, is only affected to a lesser extent by akinesia and rigidity and often presents with a slower progression of the disease.Citation42,Citation43 Thus, classic antiparkinsonian medication might be ineffective. Additionally, there are patients having contraindications due to, for example, an uncommon manifestation like a postural tremor because of medication intolerance or as a result of psychiatric comorbidities. Therefore, at times alternative medication is required for the treatment of tremor.

Depending on the tremor manifestation and the individual patient profile, other medications can be considered for treating tremor-dominant PD patients. Propranolol, for instance, might be beneficial when there is a significant postural tremor and no concomitant cardiac problems. Also, anticholinergics are suitable when akinesia and rigidity are mild, and use is not restricted by bladder dysfunction or neuropsychiatric symptoms such as cognitive impairments. In the latter case, another possible medication is clozapine, which appears to be effective in many cases for treating tremor.Citation44 Clozapine is particularly beneficial when patients manifest tremor and psychosis and when possibly life-threatening side effects are monitored cautiously. However, the high demand for family physicians constitutes a significant problem in practice, making the treatment of tremor with medical options challenging.

Finally, DBS as a surgical procedure also represents a feasible therapy for tremor. Classic target points such as thalamic DBS have been abandoned lately in favor of DBS of the subthalamic nucleus (STN-DBS), as the latter addresses tremor as well as akinesia and rigidity, while the former target lacks efficiency for therapy of these symptoms.Citation45 However, when tremor is the dominant source of disability, thalamic DBS still constitutes a feasible and very efficacious therapy option in refractory tremor or when contraindications against medical treatment are present.

Axial motor signs

Axial motor signs entail symptoms which affect the patient’s axis and therefore have no lateral preference (eg, akinesia, tremor). Treatment of axial motor signs is particularly challenging since there is often no good response on classical parkinsonian medication or STN-DBS.Citation1,Citation46,Citation47 This disparity might be attributable to different pathomechanisms, as nondopaminergic neurotransmitters have been postulated to play a crucial role in the emergence of freezing of gait (FoG) or camptocormia – two of the most frequent axial motor signs.

FoG

FoG is a paroxysmal phenomenon, most commonly found in patients with advanced PD; however, freezing behavior can also affect speech and the upper limbs. The underlying pathophysiology remains uncertain, causing difficulties for identifying a concrete medical or surgical target. Physical therapy and speech therapy and rehabilitation approaches for FoG are highly effective and should therefore be recommended. Several studies have been published recently which show attentional strategies and cueing being usefulCitation48–Citation50 and highly effective to overcome FoG.Citation51,Citation52 Other rehabilitative strategies address exercise in groupsCitation53 and treadmill training, and can also be recommended to patients suffering from FoG. This can be regarded independently from possible surgical or medical treatments.

The medical therapy of FoG requires a differentiation between freezing during “on” or “off” periods in the first instance. The “on” freezing can be treated by reducing medication. The “off” freezing, on the other hand, is more common and typically responds to treatments aimed at improving “on” time. Occasionally, however, levodopa deteriorates FoG and consequently it may be necessary to reduce dopaminergic medication. Furthermore, MAOB inhibitors have been associated with a decreased likelihood of developing FoG. However, these agents rarely reduce freezing behavior once it has developed.Citation54 The contradictory role of dopamine in FoG is clarified by studies that have shown that patients suffer more often from FoG when receiving DA than those treated with placebo,Citation55 yet withdrawing DA rarely improves FoG. Hence, nondopaminergic targets and drugs have been investigated including amantadine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, methylphenidate, and botulinum toxin injections in leg muscles. Although these studies have shown promising results, a solid recommendation is still impossible as the studies were small and uncontrolled (for further review see Giladi).Citation56 The difficulty in finding effective relief for freezing behavior has also led to the investigation of therapies besides medical treatment.

The surgical therapy options for FoG such as DBS might be beneficial, although results are highly controversial. Particularly forms appearing in the “off” time might be treated with STN-DBS.Citation57,Citation58 At the same time, it has been reported that FoG is induced by STN-DBS.Citation57 This situation becomes even more complicated as reducing the frequency of STN-DBS has also been reported to ameliorate FoG,Citation59 and new target points such as the pedunculopontine nucleus are under investigation, with conflicting results.Citation60 In summary, the efficacy of DBS for FoG requires further investigation. Currently, in the authors’ opinion, DBS should be considered for individual therapeutic attempts and when regular follow-up is possible for frequent changes in stimulation parameters. As previously mentioned, all surgical or medical therapy attempts should be supported by intensive physical and/or speech therapy.

Camptocormia

Camptocormia describes a severe flexion of the trunk, presenting in a sitting position but classically worsening when standing or walking. There are several possible theories explaining camptocormia, such as paraspinal myopathy, axial dystonia, or drug-induced forms. To date, however, there is no consistent pathophysiological concept available. This lack of understanding and few high-standard studies make all recommendations rely on empirical knowledge. The adjustment of dopaminergic therapy (controlled release levodopa therapy or levodopa with entacapone) has been reported to not only improve lateral symptoms but also camptocormia;Citation61 other patients profit from the injection of botulinum toxin into rectal abdominal muscles, emphasizing a dystonic component in its genesis.Citation62 In the authors’ own experience, however, patients describe physical exercise and the use of equipment such as walkers or rollators as helpful, especially when the handle bars are adjusted to a high position.

All presented results of the treatment of special motor restraints such as dyskinesias, tremor, or axial motor signs can be found in .

Table 3 Treatment of special motor restraints in Parkinson’s disease patients

Medical treatment of nonmotor symptoms in PD

Sleep disorders

Different forms of sleep disorders can be detected among patients suffering PD and can also possibly indicate a clinical symptom. Rapid eye movement behavior disorder, for instance, shows a higher prevalence in PD and half of all rapid eye movement behavior disorder patients will develop PD, dementia with Lewy bodies, or multiple system atrophy within 10 years. Hence, α-synuclein pathology possibly starts decades before the first motor symptoms.Citation63 Possible therapy of rapid eye movement behavior disorder consists in adding clonazepam (0.5–2.0 mg at night), which might reduce the symptoms significantly.Citation64

Nevertheless, insomnia in PD is the most common sleep disorder. It involves difficulty with initiation, duration, and/or maintenance of sleep, and consequent daytime somnolence. In PD, and due to dopaminergic deficiency, levodopa in a controlled release formulation at night is possibly efficacious, although there are controversial results.Citation28 For DAs, there is a lack of controlled studies. Only pergolide should not be used; it improves sleep mildly but its use is accompanied by a considerable number of adverse events.Citation28 Additionally, side effects of DAs especially, but also levodopa (eg, excessive daytime sleepiness, sudden onset of sleep), have a severe repercussion on QOL. This should be kept in mind when prescribing medication at first instance. Other drugs tested during recent years without direct effect on dopamine, such as eszopiclone or melatonin, did not show any conclusive results in terms of efficacy for treating insomnia and cannot be recommended.Citation65

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) can also be detected more frequently in PD patients. RLS leads to an irresistible urge to move the legs accompanied by uncomfortable sensations worsened at rest and exacerbated in the evening or at night. Therapy for RLS associated with PD is the same as in other forms and includes general measures such as maintaining a regular sleep pattern, moderate exercise, massaging the legs, and using heating pads or ice packs. Possible medications are levodopa, benzodiazepine, gabapentin, opioids, and pregabalin.Citation66 DAs or gabapentin enacarbil as a first-line medical option show very good results. The former are particularly useful as they treat motor symptoms and RLS at the same time. In addition, it has been shown that in long-term treatment, some DAs cause less augmentation compared to levodopa.Citation67 This phenomenon depicts worsening of RLS and the spread to previously unaffected parts of the body. DBS for treating RLS cannot be recommended as there are inconclusive results and some authors suspect manifestation after electrode implantation, possibly due to the reduction of dopaminergic therapy.Citation71 Hence, the role of DBS for treatment in RLS remains elusive.

However, as STN-DBS provides regular dopaminergic stimulation and therefore improves nocturnal mobility and/or dystonic symptoms, it might be helpful for reducing unease in PD patients.Citation68,Citation69 Apart from subjective improvement, there are also objective measurements showing better sleep quality.Citation70 Therefore STN-DBS might be helpful, compared to thalamic high-frequency stimulation of the thalamus, which does not influence sleep.Citation72

Lastly, advice about sleep hygiene, treatment of concomitant depression, and the reduction of hypnosedative agents are all considered common sense measures.Citation73 Medical interventions for improvement of sleep problems in PD are listed in .

Table 4 Treatment of sleep disorders in Parkinson’s disease patients

Excessive daytime sleepiness

Patients treated with DA or levodopa often experience excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden onset of sleep as side effects. However, sleep disturbances and possible changes in daytime alertness were already described by James Parkinson and might therefore be a symptom of the disease itself. Medications aiming to reduce excessive daytime sleepiness are rare. Modafinil has been tested as a possible treatment, providing inconclusive results and therefore not recommended. It is important to keep in mind the rare dermal side effects (eg, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, drug rash with eosinophilia, systematic symptoms) and the risk of inducing mania, delusions, hallucinations, and/or aggression.Citation65 In the authors’ opinion, the only possible advice so far is to reduce dopaminergic medication as far as needed and possibly switch to alternative medications as far as practicable.

Autonomic dysfunctions in PD

Autonomic dysfunction constitutes important constraints in the course of PD. The possible cause are Lewy bodies in brain areas involved in the control of vegetative functions, such as the hypothalamus or the dorsal vagus nucleus, but also in the spinal cord, sympathetic ganglia, and the plexus of the digestive tract.Citation74 The most common autonomic symptoms are orthostatic dizziness, gastrointestinal problems, and bladder and erectile dysfunction.

Concerning orthostatic hypotension and dizziness, nonpharmacological interventions should be attempted first, such as sleeping in a head-up position, fragmentation of meals, avoidance of low sodium and carbohydrate-rich meals, increased water (2–2.5 L/day) and salt intake (>8 g or 150 mmol/L), or wearing support stockings. For medication, fludrocortisone and domperidone might have beneficial effects.Citation75

In contrast, urinary disturbances should be treated primarily with proper medications. These constraints are not only very frequent but also have a severe impact on QOL. Therapeutic options are an optimization of dopaminergic therapy, as this might improve storage properties in PD patients.Citation76,Citation77 However, study results are contradictory. An alternative might be the prescription of peripherally acting anticholinergics such as trospium chloride (10–20 mg two to three times daily) or oxybutynin (2.5–5 mg twice daily). Nevertheless, there are not enough high-standard studies to assure efficacy.

Other frequent autonomic dysfunctions are gastrointestinal motility problems in PD. Therapy constitutes different approaches: constipation can be treated with macrogol effectively,Citation65 while nausea and/or vomiting in connection with the initial intake of levodopa can be antagonized by domperidone or ondasetron.Citation78 Dysphagia in late stages of PD is also a very disabling and potentially harmful symptom, as malnutrition, dehydration, aspiration, or even asphyxia may occur. Management includes a sufficient dopaminergic therapy, injection of botulinum toxin,Citation79 and different forms of rehabilitative treatments.Citation80 Enteral feeding options such as a short-term nasogastric feeding tube or long-term feeding system (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) can be considered as a final option.

For erectile dysfunction, sildenafil or other phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors might be efficacious when considering side effects/contraindications and interactions with other medications.Citation81

The effects of STN-DBS on autonomic symptoms are currently being investigated and, to date, have been considered as investigational. A summary of medical options, their adverse effects, and the level of evidence can be found in .

Table 5 Treatment of autonomic dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease patients

Psychiatric comorbidity in PD patients and its treatment

Impulse control disorders, dopamine dysregulation syndrome, and punding

Possible long-term side-effects of dopaminergic treatment in PD are impulse control disorders, punding, or dopamine dysregulation syndrome. The latter describes craving for dopaminergic medication when medication effects are at its peak, but also other behavioral symptoms such as hypomania, hypersexuality and/or gambling, and dysphoria. In contrast, fatigue or apathy might occur towards the end of the dopaminergic effect.Citation82,Citation83 Therefore, therapy recommendations include the reduction of dopaminergic therapy, in particular the switch from DA to levodopa. Amantadine as an add-on to dopaminergic treatment might also reduce impulsivity and compulsiveness, although this has only been proven so far in a small number of patients.Citation84 Lastly, in the authors’ own experience, low dosage of an antipsychotic agent (eg, quetiapine 25–50 mg at night) also helps stabilizing such symptoms with only rare side effects, although no clinical trials are yet available in this context.Citation65

Medication-induced psychosis

Psychotic disorders are rare in untreated PD patientsCitation85 but more common after initiation of dopaminergic medication.Citation86 Besides treatment with levodopa and/or DAs, further predisposing risk factors for psychosis in PD are older age,Citation87–Citation89 increasing severity of cognitive impairment or dementia,Citation88,Citation90 disease severity,Citation88,Citation89,Citation91 and polypharmacy.Citation86

Psychosis occurs in two different manifestations: (1) PD patients experiencing visual perceptual changes or visual hallucinations only (although other forms of hallucination can also occur);Citation90 and (2) patients classically presenting dementia and experiencing complex psychotic symptoms, including both hallucinations and systematized persecutory delusions in the context of dementia.Citation92 Dementia with Lewy bodies requires special mention as the cognitive decline progresses faster than in classical PD, and these patients tend to develop psychosis with delusions.Citation91 Compared to the first group, patients suffering from dementia with Lewy bodies and patients with complex psychotic symptoms typically do not have insight into their psychosis. However, once psychotic symptoms emerge, therapy for psychosis does not differ significantly between both groups.

General therapeutic recommendations include the switch to PD treatments with a smaller potential to enhance psychosis and the search for its underlying reasons. It is important to keep in mind that metabolic disorders or infection can be responsible – but also easily manageable – reasons for acute psychotic symptoms. Therefore, they should be ruled out before initiation of antipsychotic therapy. This is particularly important as classical neuroleptics have a substantial antidopaminergic effect, making their use in PD complicated.

Nevertheless, antipsychotics and especially atypical ones can and should be utilized. For example, clozapine has proven efficacious in several studies against psychotic symptoms.Citation21,Citation93 Its risk of potential life-threatening agranulocytosis makes regular follow-up inevitable. Alternatives with a better risk profile are therefore highly desirable. As such, quetiapine has emerged during the last few decades, showing good effects in some small-sized and short-term studies;Citation65,Citation94,Citation95 in one study demonstrating similar benefits to those observed with clozapine.Citation96 However, there are also results showing no superiority to placebo.Citation95 Hence, a recommendation is not possible currently and awaits further research. Finally, in special cases, possible agents are also cholinesterase inhibitors, which have demonstrated a decrease in hallucinations in patients suffering from dementia with Lewy bodies.Citation97

Antidementive therapy in PD

Cognitive decline is one of the most disabling symptoms in PD during the later stagesCitation98 and, as such, an important symptom to be treated. One of the underlying reasons might be the spread of neurodegeneration with cortical cholinergic deficiency.Citation99 Thus, anticholinergics and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) should be replaced where possible as they deteriorate cognitive performance. Available therapies for treating dementia are scarce and only two groups of medications are available. First, cholinesterase inhibitors – especially rivastigmine, which have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of cognitive impairment in PD.Citation100 Other cholinesterase inhibitors were either not tested systematically (eg, galantamine) or showed conflicting results (eg, donepezil) and are therefore not recommended.Citation65 Also, it needs to be kept in mind that all cholinesterase inhibitors should be monitored cautiously as a worsening of tremor, autonomic dysfunction, and the induction of psychosis are possible. The second structure to be targeted is N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor. Memantine as an N-methyl-D-aspartic acid antagonist appears to have a modest improvement in cognitive performance in PD patientsCitation101,Citation102 and might be considered for improving cognition and general clinical impression.

Antidepressive therapy in PD

Depression is a common manifestation either as preclinical symptomCitation103 or during the course of PD. Prevalence ranges between 2.7% and 90%, depending on diagnosis criteria and the types of depressive disorders included. In any case, many PD patients consider QOL most impaired by their decreased emotional state.Citation104 Yet, depression in PD is independent of motor symptomsCitation105,Citation106 and should therefore be addressed separately; nevertheless, sufficient dopaminergic therapy needs to be ensured due to the importance of dopamine in the limbic system.Citation107 One possible way of addressing both problems might be pramipexole, as it helps with motor symptoms and has showed an antidepressant effect in experimental animal modelsCitation108,Citation109 as well as in clinical routine.Citation110 For the clinical efficacy of actual antidepressants, there are only sparse high-standard studies. TCAs such as desipramine and nortriptyline have proven effective in improving depressive mood.Citation65 However, their use is restricted in many cases by side effects such as cognitive impairment, autonomic dysfunction, and orthostatic dysregulation. Therefore, TCAs should be used carefully, particularly in elderly PD patients. Alternatively, treatment with modern antidepressants has also provided good results in clinical routine. Again, systematic studies are lacking and side effects include a possible interaction with MAOB inhibitors, leading to a serotonin syndrome. Nevertheless, these are very unlikely risks compared to those listed in older antidepressants (eg, TCA). Lastly, modern antidepressants such as atomoxetine could not show any beneficial effect on depression in PD patients and should therefore not be considered. Drugs such as omega-3 or interventions with transcranial magnetic stimulation have to be regarded, to date, experimental.Citation65 In summary, although high-standard studies are missing, the authors’ would rather use modern antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to treat depression and/or, whenever possible, switch to pramipexole.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the basis of every antidepressant therapy should be an introduction to educational programs. These programs should be considered even in early stages of PD without heavy motor impairments and should, in particular, include the improvement of coping strategies regarding PD symptoms.

A summary of available pharmaceutical options against psychiatric comorbidities in PD can be found in .

Table 6 Treatment of concomitant psychiatric symptoms in Parkinson’s disease patients

Other therapeutic options in PD

Pump therapy in PD

Motor fluctuations and/or dyskinesias range among the major concerns in the management of advanced PD, as stated above. An underlying mechanism might be fluctuating plasmatic dopamine concentrations with oral intake; therefore, two different forms of continuous nonoral applications have been developed and tested recently: the apomorphine pump and the levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) pump.

General indications for apomorphine infusion and LCIG (but also DBS) in PD are quite similar: patients with significant effect on dopaminergic medication and pronounced motor fluctuations not responding to classical pharmacological therapy. Contraindications differ significantly between DBS and pump therapies; older patients and significant psychiatric or cognitive problems are generally considered as contraindications for DBS but with regular follow-up and monitoring are not necessarily contraindications for infusional treatments and LCIG in particular.Citation111

LCIG

Intestinal infusion of LCIG is an efficacious way of treating motor symptoms, as it has the same mechanisms of action as oral levodopa administration. Therefore, LCIG is infused into the proximal jejunum by means of a portable pump through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube,Citation111,Citation112 although temporary application via nasoduodenal for testing of clinical response is also possible. Besides the efficacy in motor symptoms, nonmotor symptoms as well as QOL seem to be ameliorated.Citation113 However, results have to be regarded carefully, since many of the available data originate from open-label and/or observational studies. In the authors’ opinion, this method is especially suited for older patients with late sequelae of levodopa therapy such as motor complications and for patients with a high risk of hallucinations.

Apomorphine pump

Apomorphine is a potent DA showing good efficacy for treating motor symptoms in PD. It is characterized by reaching its plasmatic maximum in less than 10 minutes after subcutaneous application. Therefore, apomorphine rapidly increases the duration of “on” phases and is effectively applicable to patients with motor fluctuations.Citation114,Citation115

Two methods are available: (1) subcutaneous apomorphine injections “on demand;” or (2) continuous subcutaneous injection by means of a pump. Both forms might cause side effects, the most frequent being nausea and vomiting. This can be addressed effectively by administering domperidone several days before the first application. Another important problem to be considered is the emergence of cutaneous nodules in almost 100% of the cases, leading not only to a cosmetic problem but also to worse resorption. As a consequence, a regular change of the injection side is unavoidable. Eventually, psychiatric effects from hallucinations to acute psychotic syndrome may occur particularly in patients with preexisting psychiatric conditions. Taken together, and due to the common comorbidity of motor fluctuations and psychiatric symptoms in later stages of PD, the use of apomorphine is hence restricted. For patients suffering from motor complications, apomorphine is, nevertheless, a good choice providing satisfactory immediate and long-term results.Citation116

Functional surgery in PD

In recent years, DBS has emerged as efficacious therapy for different medically refractory neurological symptoms using current pulses in different target areas. Origins of DBS go back to lesional/ablative approaches under which improvement of both tremor (eg, after thalamotomy) and akinesia/rigidity (eg, via pallidotomy) could be achieved. The mechanisms of action remain elusive but different approaches are discussed: (1) depolarizing blockade, (2) synaptic inhibition, (3) synaptic depression, and (4) simulation-induced disruption of pathological network activity.Citation117 From a clinician’s point of view, in contrast, additional questions need to be answered, as there are different areas to be targeted and these involve distinct “pros” and “cons.” Therefore, side effects or the best moment for surgery are nowadays subject of intensive investigation.

Target points and specific side effects

There are no guidelines for the target structure for DBS in PD. Different arguments can be used for an appropriate and individual clinical decision.

STN

Today, STN is considered the most effective for DBS in PD as it improves all cardinal symptoms. Also, it provides better long-term results in motor outcome compared to the classic target point – the internal globus pallidus (GPi). In addition, the STN shows less decay of motor efficacy in long-term studies.Citation118,Citation119 From a short-term perspective, however, there are side effects due to the small size of the STN and the stimulation of adjacent structures as well as functional loops interconnected within the STN. Limbic and affective loops in particular seem to be afflicted by stimulation, leading to postoperative dysphoria and hypomaniaCitation120 and a higher risk of suicide.Citation121 In addition, cognitive decline has been attributed to STN-DBS, particularly in patients with advanced age, higher dopaminergic medications, and higher axial subscores of the Unified PD Rating Scale.Citation122 The reasons are unclear, although due to the heterogeneous results, electrode localization and/or the trajectory through the frontal lobe has been speculated playing a role in cognitive decline.Citation123 As a result, STN is indicated as an effective target when younger patients suffer from severe motor complications, such as dyskinesias or fluctuations.

GPi

The original operative PD treatment, the GPi has lost importance – compared to STN-DBS – due to its disadvantages. This was due to worse long-term results,Citation118,Citation119 higher energy consumption, and the lack of possibility in reducing dopaminergic medications drastically with GPi-DBS. However, during the last few years, GPi-DBS is regaining importance for several reasons. First, GPi is easier to target, since it is a bigger structure than STN. Secondly, patients operated on in the GPi are less prone to develop psychiatric and cognitive implications. And finally, GPi-DBS appears to be more efficient in treating some of the nonmotor symptoms in PD. Also, worse long-term results could not be replicated in other studies.Citation124 Therefore, GPi will be possibly targeted in the future more frequently and should be taken into account in elderly patients who might develop psychiatric or cognitive impairments.

Ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus (VLp)

The thalamus was the traditional target for stereotactic tremor surgery as ablative procedures in the VLp* showed good efficacy, and stimulation has also consistently shown long-lasting therapy of contralateral tremor. However, the structure has lost its importance in PD since other cardinal symptoms are not modified to the same extent. Therefore, VLp-DBS should only be considered in patients suffering from severe tremor and when other options appear less practicable. Advantages are mainly the fewer aforementioned side effects during VLp-DBS compared to equally effective target points such as STN or GPi.Citation45 Possible side effects of this target are on the one hand a stimulation of structures in the vicinity of the VLp with resulting dysarthria, paresthesias, or gait disturbances and on the other hand mild executive deficits (eg, in verbal fluency).Citation126 Therefore exact planning and meticulous intraoperative testing of tremor-dominant and elderly patients is required in order to stimulate segregated motor loops.Citation4,Citation127

Pedunculopontine nucleus

This brain area was introduced as an additional DBS target, with the purpose of ameliorating axial symptoms responding in an unsatisfactory way to DBS of other structures or medical treatment.Citation128,Citation129 So far, it has been practiced as an add-on to STN-DBS, providing controversial results.Citation130,Citation131 Therefore, no recommendation on DBS in the pedunculopontine nucleus can be made at this point.

General considerations

The safety and efficacy of DBS in PD has been proven not least because of the clinical experience with thousands of patients. However, there are several different open and general questions concerning DBS. For instance, there is still an open debate on how many targets should be operated on. As PD is a lateral disease, some centers conduct unilateral electrode implantation as studies have demonstrated unilateral DBS being associated with better QOLCitation132 and reduced surgery time. On the other hand, PD is a progressive disease which spreads to both sides, therefore making a second electrode in later stages necessary. This, however, leads to duplicated operation risks and therefore higher economic expenses for health care systems. Concerning medical issues, in contrast, there are no short-term differences for motor outcome between unilateral and bilateral implantation.Citation133,Citation134 All in all, and subject to limited exceptions, the authors therefore plead in favor of a bilateral implantation.

However, having determined the amount of targets leads to the question as to when is the best moment for surgery. Nowadays, DBS is only practiced in patients suffering from medically refractory motor restraints. However, there is growing evidence that although not neuroprotective,Citation135 DBS leads to a better QOL.Citation136–Citation138 Therefore, it is conceivable that early stimulation has great repercussions on QOL. Preliminary results of an international randomized and multicenter study (Controlled Trial of Deep Brain Stimulation in Early Patients With Parkinson’s Disease; EARLYSTIM study) have been recently presented and the final results are expected in the near future.Citation176 Nevertheless, the risks of precipitated electrode implantation should be pointed out. First, there is a disproportional risk of confounding other or atypical parkinsonian syndromes in the first years of symptoms. And secondly, it should be kept in mind that patients can continue functioning well for years with only medical treatment without being exposed to the risks of surgery.

Regarding these open questions, the decision for surgery should be made by an interdisciplinary team. In the authors’ center, neurologists, neurosurgeons, psychiatrists, and other specialists – depending on the underlying problems (eg, physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist, social worker) – are involved in the decision. In addition, past medical history, current comorbidities, imaging studies, and the Unified PD Rating Scale in the “on” and “off” condition should be carefully considered when it comes to decide whether or not to operate, or which structure to target in PD patients. The authors believe that this increases the quality and the outcomes of this procedure, and therefore patients obtain satisfying results.

Summary

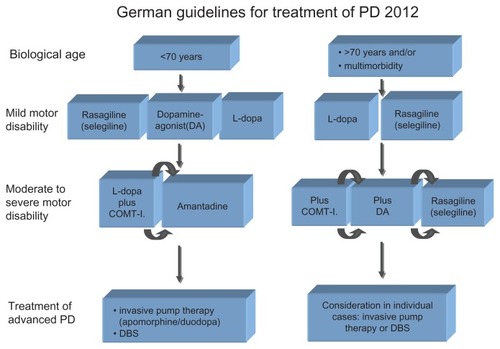

In summary, as the possibilities have increased dramatically in the last decades, first attempts to alleviate motor symptoms with just levodopa have been abandoned. Although still considered the most effective drug, the awareness of possible long-term risks has led to more sophisticated regimens with additional agents and additional therapeutic options such as infusional therapies or DBS. For a practical approach, the current German guidelines for PD therapy are referred to ().

Figure 1 German guidelines for treatment of PD 2012.

However, it needs to be remembered that such schemes are not suited for tailoring the best individual medication. The reason for this is that they focus on the treatment of the cardinal motor symptoms and do not include other therapeutic targets. Yet, the awareness of additional restraints and nonmotor symptoms is important, as they are often perceived as highly impairing. It therefore results in an even more complex situation for physicians, as every patient needs their risk profile and concomitant diseases considered.

Finally, as current therapies improve QOL and motor restraints in early stages of the disease, physicians face the problem of additional problems and long-term side effects in later stages. In many cases, these circumstances are especially challenging as there is currently no effective response. Therefore, further investigation is highly desirable in order to develop even better therapies which allow the modification of the neurodegenerative processes and provide solutions for the existing additional motor and nonmotor symptoms in PD patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BraakHDel TrediciKRubUde VosRAJansen SteurENBraakEStaging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s diseaseNeurobiol Aging200324219721112498954

- KaufmanMJMadrasBKSevere depletion of cocaine recognition sites associated with the dopamine transporter in Parkinson’s-diseased striatumSynapse19919143491796351

- NiznikHBFogelEFFassosFFSeemanPThe dopamine transporter is absent in parkinsonian putamen and reduced in the caudate nucleusJ Neurochem19915611921981987318

- EggersCPedrosaDJKahramanDParkinson subtypes progress differently in clinical course and imaging patternPLoS One2012710e4681323056463

- RajputAHVollARajputMLRobinsonCARajputACourse in Parkinson disease subtypes: a 39-year clinicopathologic studyNeurology200973320621219620608

- AshburnAFazakarleyLBallingerCPickeringRMcLellanLDFittonCA randomised controlled trial of a home based exercise programme to reduce the risk of falling among people with Parkinson’s diseaseJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200778767868417119004

- CakitBDSaracogluMGencHErdemHRInanLThe effects of incremental speed-dependent treadmill training on postural instability and fear of falling in Parkinson’s diseaseClin Rehabil200721869870517846069

- EbersbachGEbersbachAEdlerDComparing exercise in Parkinson’s disease – the Berlin LSVT®BIG studyMov Disord201025121902190820669294

- EllisTde GoedeCJFeldmanRGWoltersECKwakkelGWagenaarRCEfficacy of a physical therapy program in patients with Parkinsons disease: a randomized controlled trialArch Phys Med Rehabil200586462663215827910

- MorrisMEIansekRKirkwoodBA randomized controlled trial of movement strategies compared with exercise for people with Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord2009241647118942100

- BarbeMTCepuranFAmarellMSchoenauETimmermannLLong-term effect of robot-assisted treadmill walking reduces freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease patients: a pilot studyJ Neurol2013260129629823070468

- TomlinsonCLPatelSMeekCPhysiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson’s diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20127CD00281722786482

- ChrispPMammenGJSorkinEMSelegiline. A review of its pharmacology, symptomatic benefits and protective potential in Parkinson’s diseaseDrugs Aging1991132282481794016

- YoudimMBBar AmOYogev-FalachMRasagiline: neurodegeneration, neuroprotection, and mitochondrial permeability transitionJ Neurosci Res2005791–217217915573406

- ZouLJankovicJRoweDBXieWAppelSHLeWNeuroprotection by pramipexole against dopamine- and levodopa-induced cytotoxicityLife Sci199964151275128510227583

- BealMFMatthewsRTTielemanAShultsCWCoenzyme Q10 attenuates the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) induced loss of striatal dopamine and dopaminergic axons in aged miceBrain Res199878311091149479058

- OlanowCWRascolOHauserRA double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s diseaseN Engl J Med2009361131268127819776408

- Parkinson Study GroupA controlled, randomized, delayed-start study of rasagiline in early Parkinson diseaseArch Neurol200461456156615096406

- SchapiraAHAlbrechtSBaronePRationale for delayed-start study of pramipexole in Parkinson’s disease: the PROUD studyMov Disord201025111627163220544810

- HartRGPearceLARavinaBMYalthoTCMarlerJRNeuroprotection trials in Parkinson’s disease: systematic reviewMov Disord200924564765419117366

- GoetzCGPoeweWRascolOSampaioCEvidence-based medical review update: pharmacological and surgical treatments of Parkinson’s disease: 2001 to 2004Mov Disord200520552353915818599

- AdlerCHSingerCO’BrienCRandomized, placebo-controlled study of tolcapone in patients with fluctuating Parkinson disease treated with levodopa–carbidopa. Tolcapone Fluctuator Study Group IIIArch Neurol1998558108910959708959

- DeaneKHSpiekerSClarkeCECatechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors for levodopa-induced complications in Parkinson’s diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20044CD00455415495119

- KurthMCAdlerCHHilaireMSTolcapone improves motor function and reduces levodopa requirement in patients with Parkinson’s disease experiencing motor fluctuations: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Tolcapone Fluctuator Study Group INeurology199748181879008498

- FahnSOakesDShoulsonILevodopa and the progression of Parkinson’s diseaseN Engl J Med2004351242498250815590952

- TalatiRBakerWLPatelAAReinhartKColemanCIAdding a dopamine agonist to preexisting levodopa therapy vs levodopa therapy alone in advanced Parkinson’s disease: a meta analysisInt J Clin Pract200963461362319222614

- KvernmoTHoubenJSylteIReceptor-binding and pharmacokinetic properties of dopaminergic agonistsCurr Top Med Chem20088121049106718691132

- FoxSHKatzenschlagerRLimSYThe Movement Disorder Society evidence-based medicine review update: treatments for the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord201126Suppl 3S2S4122021173

- MollerJCOertelWHKosterJPezzoliGProvincialiLLong-term efficacy and safety of pramipexole in advanced Parkinson’s disease: results from a European multicenter trialMov Disord200520560261015726540

- HollowayRGShoulsonIFahnSPramipexole vs levodopa as initial treatment for Parkinson disease: a 4-year randomized controlled trialArch Neurol20046171044105315262734

- HauserRARascolOKorczynADTen-year follow-up of Parkinson’s disease patients randomized to initial therapy with ropinirole or levodopaMov Disord200722162409241717894339

- OlanowCWWatkinsPBTolcapone: an efficacy and safety review (2007)Clin Neuropharmacol200730528729417909307

- ReichmannHBoasJMacmahonDMyllylaVHakalaAReinikainenKEfficacy of combining levodopa with entacapone on quality of life and activities of daily living in patients experiencing wearing-off type fluctuationsActa Neurol Scand20051111212815595934

- SnowBJMacdonaldLMcauleyDWallisWThe effect of amantadine on levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled studyClin Neuropharmacol2000232828510803797

- LugingerEWenningGKBoschSPoeweWBeneficial effects of amantadine on L-dopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord200015587387811009193

- HauserRACantillonMPourcherEPreladenant in patients with Parkinson’s disease and motor fluctuations: a phase 2, double-blind, randomised trialLancet Neurol201110322122921315654

- HodgsonRABedardPJVartyGBPreladenant, a selective A(2A) receptor antagonist, is active in primate models of movement disordersExp Neurol2010225238439020655910

- PostumaRBLangAEMunhozRPCaffeine for treatment of Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trialNeurology201279765165822855866

- OlanowCWObesoJAStocchiFDrug insight: continuous dopaminergic stimulation in the treatment of Parkinson’s diseaseNat Clin Pract Neurol20062738239216932589

- OndoWGSethiKDKricorianGSelegiline orally disintegrating tablets in patients with Parkinson disease and “wearing off” symptomsClin Neuropharmacol200730529530017909308

- CrosbyNDeaneKHClarkeCEAmantadine in Parkinson’s diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20031CD00346812535476

- PedrosaDJReckCFlorinEEssential tremor and tremor in Parkinson’s disease are associated with distinct “tremor clusters” in the ventral thalamusExp Neurol2012237243544322809566

- HelmichRCJanssenMJOyenWJBloemBRToniIPallidal dysfunction drives a cerebellothalamic circuit into Parkinson tremorAnn Neurol201169226928121387372

- Parkinson Study GroupLow-dose clozapine for the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s diseaseN Engl J Med19993401075776310072410

- HarizMIKrackPAleschFMulticentre European study of thalamic stimulation for parkinsonian tremor: a 6 year follow-upJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200879669469917898034

- PillonBDuboisBBonnetAMCognitive slowing in Parkinson’s disease fails to respond to levodopa treatment: the 15-objects testNeurology19893967627682725868

- LevyGLouisEDCoteLContribution of aging to the severity of different motor signs in Parkinson diseaseArch Neurol200562346747215767513

- RahmanSGriffinHJQuinnNPJahanshahiMThe factors that induce or overcome freezing of gait in Parkinson’s diseaseBehav Neurol200819312713618641432

- NieuwboerAKwakkelGRochesterLCueing training in the home improves gait-related mobility in Parkinson’s disease: the RESCUE trialJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200778213414017229744

- AriasPCudeiroJEffect of rhythmic auditory stimulation on gait in parkinsonian patients with and without freezing of gaitPLoS One201053e967520339591

- NieuwboerABakerKWillemsAMThe short-term effects of different cueing modalities on turn speed in people with Parkinson’s diseaseNeurorehabil Neural Repair200923883183619491396

- NieuwboerACueing for freezing of gait in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a rehabilitation perspectiveMov Disord200823Suppl 2S475S48118668619

- AllenNECanningCGSherringtonCThe effects of an exercise program on fall risk factors in people with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled trialMov Disord20102591217122520629134

- GiladiNMcDermottMPFahnSFreezing of gait in PD: prospective assessment in the DATATOP cohortNeurology200156121712172111425939

- JankovicJLong-term study of pergolide in Parkinson’s diseaseNeurology19853532962993974887

- GiladiNMedical treatment of freezing of gaitMov Disord200823Suppl 2S482S48818668620

- FerrayeMUDebuBFraixVEffects of subthalamic nucleus stimulation and levodopa on freezing of gait in Parkinson diseaseNeurology20087016 Pt 21431143718413568

- DavisJTLyonsKEPahwaRFreezing of gait after bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation for Parkinson’s diseaseClin Neurol Neurosurg2006108546146416139421

- MoreauCDefebvreLDesteeASTN-DBS frequency effects on freezing of gait in advanced Parkinson diseaseNeurology2008712808418420482

- FerrayeMUDebuBFraixVEffects of pedunculopontine nucleus area stimulation on gait disorders in Parkinson’s diseaseBrain2010133Pt 120521419773356

- FinstererJStroblWPresentation, etiology, diagnosis, and management of camptocormiaEur Neurol20106411820634620

- JankovicJCamptocormia, head drop and other bent spine syndromes: heterogeneous etiology and pathogenesis of parkinsonian deformitiesMov Disord201025552752820425791

- ClaassenDOJosephsKAAhlskogJESilberMHTippmann-PeikertMBoeveBFREM sleep behavior disorder preceding other aspects of synucleinopathies by up to half a centuryNeurology201075649449920668263

- OlsonEJBoeveBFSilberMHRapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder: demographic, clinical and laboratory findings in 93 casesBrain2000123Pt 233133910648440

- SeppiKWeintraubDCoelhoMThe Movement Disorder Society evidence-based medicine review update: treatments for the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord201126Suppl 3S42S8022021174

- AuroraRNKristoDABistaSRThe treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in adults – an update for 2012: practice parameters with an evidence-based systematic review and meta-analyses: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice GuidelineSleep20123581039106222851801

- OertelWTrenkwalderCBenesHLong-term safety and efficacy of rotigotine transdermal patch for moderate-to-severe idiopathic restless legs syndrome: a 5-year open-label extension studyLancet Neurol201110871072021705273

- ArnulfIBejjaniBPGarmaLImprovement of sleep architecture in PD with subthalamic nucleus stimulationNeurology200055111732173411113233

- IranzoAValldeoriolaFSantamariaJTolosaERumiaJSleep symptoms and polysomnographic architecture in advanced Parkinson’s disease after chronic bilateral subthalamic stimulationJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200272566166411971059

- MonacaCOzsancakCJacquessonJMEffects of bilateral subthalamic stimulation on sleep in Parkinson’s diseaseJ Neurol2004251221421814991357

- KediaSMoroETagliatiMLangAEKumarREmergence of restless legs syndrome during subthalamic stimulation for Parkinson diseaseNeurology200463122410241215623715

- ArnulfIBejjaniBPGarmaLEffect of low and high frequency thalamic stimulation on sleep in patients with Parkinson’s disease and essential tremorJ Sleep Res200091556210733690

- LarsenJPTandbergESleep disorders in patients with Parkinson’s disease: epidemiology and managementCNS Drugs200115426727511463132

- WakabayashiKTakahashiHOhamaETakedaSIkutaFLewy bodies in the visceral autonomic nervous system in Parkinson’s diseaseAdv Neurol1993606096128420198

- LahrmannHCortelliPHilzMMathiasCJStruhalWTassinariMEFNS guidelines on the diagnosis and management of orthostatic hypotensionEur J Neurol200613993093616930356

- ArandaBCramerPEffects of apomorphine and L-dopa on the parkinsonian bladderNeurourol Urodyn19931232032098330043

- ChristmasTJKempsterPAChappleCRRole of subcutaneous apomorphine in parkinsonian voiding dysfunctionLancet198828626–8627145114532904571

- SoykanISarosiekIShifflettJWootenGFMcCallumRWEffect of chronic oral domperidone therapy on gastrointestinal symptoms and gastric emptying in patients with Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord19971269529579399220

- RestivoDAPalmeriAMarchese-RagonaRBotulinum toxin for cricopharyngeal dysfunction in Parkinson’s diseaseN Engl J Med2002346151174117511948283

- El SharkawiARamigLLogemannJASwallowing and voice effects of Lee Silverman Voice Treatment (LSVT): a pilot studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry2002721313611784821

- BrigantiASaloniaAGallinaADrug insight: oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunctionNat Clin Pract Urol20052523924716474835

- LawrenceADEvansAHLeesAJCompulsive use of dopamine replacement therapy in Parkinson’s disease: reward systems gone awry?Lancet Neurol200321059560414505581

- EvansAHLeesAJDopamine dysregulation syndrome in Parkinson’s diseaseCurr Opin Neurol200417439339815247533

- ThomasABonanniLGambiFDi IorioAOnofrjMPathological gambling in Parkinson disease is reduced by amantadineAnn Neurol201068340040420687121

- CummingsJLBehavioral complications of drug treatment of Parkinson’s diseaseJ Am Geriatr Soc19913977087162061539

- HendersonMJMellersJDCPsychosis in Parkinson’s disease: “between a rock and a hard place.”Int Rev Psychiatry2000124319334

- Sanchez-RamosJROrtollRPaulsonGWVisual hallucinations associated with Parkinson diseaseArch Neurol19965312126512688970453

- PacchettiCManniRZangagliaRRelationship between hallucinations, delusions, and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord200520111439144816028215

- AarslandDLarsenJPCumminsJLLaakeKPrevalence and clinical correlates of psychotic symptoms in Parkinson disease: a community-based studyArch Neurol199956559560110328255

- FenelonGMahieuxFHuonRZieglerMHallucinations in Parkinson’s disease: prevalence, phenomenology and risk factorsBrain2000123Pt 473374510734005

- AarslandDBallardCLarsenJPMcKeithIA comparative study of psychiatric symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with and without dementiaInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200116552853611376470

- MarshLWilliamsJRRoccoMGrillSMunroCDawsonTMPsychiatric comorbidities in patients with Parkinson disease and psychosisNeurology200463229330015277623

- FactorSAFriedmanJHLannonMCOakesDBourgeoisKClozapine for the treatment of drug-induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: results of the 12 week open label extension in the PSYCLOPS trialMov Disord200116113513911215574

- MorganteLEpifanioASpinaEQuetiapine and clozapine in parkinsonian patients with dopaminergic psychosisClin Neuropharmacol200427415315615319699

- OndoWGTintnerRVoungKDLaiDRingholzGDouble-blind, placebo-controlled, unforced titration parallel trial of quetiapine for dopaminergic-induced hallucinations in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord200520895896315800937

- MerimsDBalasMPeretzCShabtaiHGiladiNRater-blinded, prospective comparison: quetiapine versus clozapine for Parkinson’s disease psychosisClin Neuropharmacol200629633133717095896

- BergmanJLernerVSuccessful use of donepezil for the treatment of psychotic symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s diseaseClin Neuropharmacol200225210711011981238

- AarslandDHutchinsonMLarsenJPCognitive, psychiatric and motor response to galantamine in Parkinson’s disease with dementiaInt J Geriatr Psychiatry2003181093794114533126

- BohnenNIKauferDIIvancoLSCortical cholinergic function is more severely affected in parkinsonian dementia than in Alzheimer disease: an in vivo positron emission tomographic studyArch Neurol200360121745174814676050

- EmreMAarslandDAlbaneseARivastigmine for dementia associated with Parkinson’s diseaseN Engl J Med2004351242509251815590953

- AarslandDBallardCWalkerZMemantine in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trialLancet Neurol20098761361819520613

- LeroiIOvershottRByrneEJDanielEBurnsARandomized controlled trial of memantine in dementia associated with Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord20092481217122119370737

- LemkeMRFuchsGGemendeIDepression and Parkinson’s diseaseJ Neurol2004251Suppl 6VI/24VI/27

- Global Parkinson’s Disease Survey Steering CommitteeFactors impacting on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: results from an international surveyMov Disord2002171606711835440

- KuopioAMMarttilaRJHeleniusHToivonenMRinneUKThe quality of life in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord200015221622310752569

- SchragAJahanshahiMQuinnNWhat contributes to quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease?J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200069330831210945804

- RemyPDoderMLeesATurjanskiNBrooksDDepression in Parkinson’s disease: loss of dopamine and noradrenaline innervation in the limbic systemBrain2005128Pt 61314132215716302

- MajJRogozZSkuzaGKolodziejczykKThe behavioural effects of pramipexole, a novel dopamine receptor agonistEur J Pharmacol1997324131379137910

- WillnerPLappasSCheetaSMuscatRReversal of stress-induced anhedonia by the dopamine receptor agonist, pramipexolePsychopharmacology (Berl)199411544544627871089

- LemkeMRBrechtHMKoesterJKrausPHReichmannHAnhedonia, depression, and motor functioning in Parkinson’s disease during treatment with pramipexoleJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci200517221422015939976

- AntoniniATolosaEApomorphine and levodopa infusion therapies for advanced Parkinson’s disease: selection criteria and patient managementExpert Rev Neurother20099685986719496689

- LundqvistCContinuous levodopa for advanced Parkinson’s diseaseNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat20073333534819300565

- DevosDPatient profile, indications, efficacy and safety of duodenal levodopa infusion in advanced Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord2009247993100019253412

- PoeweWKleedorferBWagnerMBoschSScheloskyLContinuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusions for fluctuating Parkinson’s disease. Long-term follow-up in 18 patientsAdv Neurol1993606566598420206

- StibeCMLeesAJKempsterPASternGMSubcutaneous apomorphine in parkinsonian on–off oscillationsLancet1988185824034062893200

- FrankelJPLeesAJKempsterPASternGMSubcutaneous apomorphine in the treatment of Parkinson’s diseaseJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry1990532961012313313

- McIntyreCCSavastaMKerkerian-Le GoffLVitekJLUncovering the mechanism(s) of action of deep brain stimulation: activation, inhibition, or bothClin Neurophysiol200411561239124815134690

- AllertNLehrkeRSturmVVolkmannJSecondary failure after ten years of pallidal neurostimulation in a patient with advanced Parkinson’s diseaseJ Neural Transm2010117334935120069437

- VolkmannJDeep brain stimulation for the treatment of Parkinson’s diseaseJ Clin Neurophysiol200421161715097290

- VolkmannJDanielsCWittKNeuropsychiatric effects of subthalamic neurostimulation in Parkinson diseaseNat Rev Neurol20106948749820680036

- VoonVKrackPLangAEA multicentre study on suicide outcomes following subthalamic stimulation for Parkinson’s diseaseBrain2008131Pt 102720272818941146

- DanielsCKrackPVolkmannJRisk factors for executive dysfunction after subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord201025111583158920589868

- YorkMKWildeEASimpsonRJankovicJRelationship between neuropsychological outcome and DBS surgical trajectory and electrode locationJ Neurol Sci20092871–215917119767016

- WeaverFMFollettKASternMRandomized trial of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: thirty-six-month outcomesNeurology2012791556522722632

- KrackPDostrovskyJIlinskyISurgery of the motor thalamus: problems with the present nomenclaturesMov Disord200217Suppl 3S2S811948749

- WojteckiLTimmermannLJorgensSFrequency-dependent reciprocal modulation of verbal fluency and motor functions in subthalamic deep brain stimulationArch Neurol20066391273127616966504

- MasonAIlinskyIAMaldonadoSKultas-IlinskyKThalamic terminal fields of individual axons from the ventral part of the dentate nucleus of the cerebellum in Macaca mulattaJ Comp Neurol2000421341242810813796

- HamaniCMoroELozanoAMThe pedunculopontine nucleus as a target for deep brain stimulationJ Neural Transm2011118101461146821194002

- StefaniALozanoAMPeppeABilateral deep brain stimulation of the pedunculopontine and subthalamic nuclei in severe Parkinson’s diseaseBrain2007130Pt 61596160717251240

- CostaACarlesimoGACaltagironeCEffects of deep brain stimulation of the peduncolopontine area on working memory tasks in patients with Parkinson’s diseaseParkinsonism Relat Disord2010161646719502095

- StefaniAPierantozziMCeravoloRBrusaLGalatiSStanzionePDeep brain stimulation of pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPTg) promotes cognitive and metabolic changes: a target-specific effect or response to a low-frequency pattern of stimulation?Clin EEG Neurosci2010412828620521490

- ZahodneLBOkunMSFooteKDGreater improvement in quality of life following unilateral deep brain stimulation surgery in the globus pallidus as compared to the subthalamic nucleusJ Neurol200925681321132919363633

- FollettKAWeaverFMSternMPallidal versus subthalamic deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s diseaseN Engl J Med2010362222077209120519680

- OkunMSFernandezHHWuSSCognition and mood in Parkinson’s disease in subthalamic nucleus versus globus pallidus interna deep brain stimulation: the COMPARE trialAnn Neurol200965558659519288469

- CharlesPDGillCEDavisTLKonradPEBenabidALIs deep brain stimulation neuroprotective if applied early in the course of PD?Nat Clin Pract Neurol20084842442618594505

- DeuschlGSchade-BrittingerCKrackPA randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s diseaseN Engl J Med2006355989690816943402

- WeaverFFollettKHurKIppolitoDSternMDeep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease: a metaanalysis of patient outcomesJ Neurosurg2005103695696716381181

- WilliamsAGillSVarmaTDeep brain stimulation plus best medical therapy versus best medical therapy alone for advanced Parkinson’s disease (PD SURG trial): a randomised, open-label trialLancet Neurol20109658159120434403

- RascolODuboisBCaldasACSennSDel SignoreSLeesAEarly piribedil monotherapy of Parkinson’s disease: a planned seven-month report of the REGAIN studyMov Disord200621122110211517013922

- Parkinson Study Group CALM Cohort InvestigatorsLong-term effect of initiating pramipexole vs levodopa in early Parkinson diseaseArch Neurol200966556357019433655

- BaronePScarzellaLMarconiRPramipexole versus sertraline in the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease: a national multicenter parallel-group randomized studyJ Neurol2006253560160716607468

- PahwaRLyonsKEOptions in the treatment of motor fluctuations and dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease: a brief reviewNeurol Clin200422Suppl 3S35S5215501365

- WolfESeppiKKatzenschlagerRLong-term antidyskinetic efficacy of amantadine in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord201025101357136320198649

- DurifFDebillyBGalitzkyMClozapine improves dyskinesias in Parkinson disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled studyNeurology200462338138814872017

- SpiekerSEisebittRBreitSTremorlytic activity of budipine in Parkinson’s diseaseClin Neuropharmacol199922211511910202609

- FriedmanJHKollerWCLannonMCBusenbarkKSwanson-HylandESmithDBenztropine versus clozapine for the treatment of tremor in Parkinson’s diseaseNeurology1997484107710819109903

- AndersonKNShneersonJMDrug treatment of REM sleep behavior disorder: the use of drug therapies other than clonazepamJ Clin Sleep Med20095323523919960644

- StocchiFBarbatoLNorderaGBerardelliARuggieriSSleep disorders in Parkinson’s diseaseJ Neurol1998245Suppl 1S15S189617717

- Ferini-StrambiLAarskogDPartinenMEffect of pramipexole on RLS symptoms and sleep: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialSleep Med20089887488118952497

- MontagnaPHornyakMUlfbergJRandomized trial of pramipexole for patients with restless legs syndrome (RLS) and RLS-related impairment of moodSleep Med2011121344020965780

- OertelWHStiasny-KolsterKBergtholdtBEfficacy of pramipexole in restless legs syndrome: a six-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study (effect-RLS study)Mov Disord200722221321917133582

- BoganRKFryJMSchmidtMHCarsonSWRitchieSYRopinirole in the treatment of patients with restless legs syndrome: a US-based randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trialMayo Clin Proc2006811172716438474

- TrenkwalderCGarcia-BorregueroDMontagnaPRopinirole in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: results from the TREAT RLS 1 study, a 12 week, randomised, placebo controlled study in 10 European countriesJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry2004751929714707315

- HeningWAAllenRPOndoWGRotigotine improves restless legs syndrome: a 6-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in the United StatesMov Disord201025111675168320629075

- OertelWHBenesHGarcia-BorregueroDRotigotine transdermal patch in moderate to severe idiopathic restless legs syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled polysomnographic studySleep Med201011984885620813583

- KushidaCABeckerPMEllenbogenALCanafaxDMBarrettRWRandomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of XP13512/GSK1838262 in patients with RLSNeurology200972543944619188575

- KushidaCAWaltersASBeckerPA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of XP13512/GSK1838262 in the treatment of patients with primary restless legs syndromeSleep200932215916819238802

- LeeDOZimanRBPerkinsATPocetaJSWaltersASBarrettRWA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and tolerability of gabapentin enacarbil in subjects with restless legs syndromeJ Clin Sleep Med20117328229221677899

- WaltersASOndoWGKushidaCAGabapentin enacarbil in restless legs syndrome: a phase 2b, 2-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialClin Neuropharmacol200932631132019667976

- WinkelmanJWBoganRKSchmidtMHHudsonJDDeRossettSEHill-ZabalaCERandomized polysomnography study of gabapentin enacarbil in subjects with restless legs syndromeMov Disord201126112065207221611981

- HoglBPaulusWClarenbachPTrenkwalderCRestless legs syndrome: diagnostic assessment and the advantages and risks of dopaminergic treatmentJ Neurol2006253Suppl 4IV22IV2816944353

- Garcia-BorregueroDLarrosaOde la LlaveYVergerKMasramonXHernandezGTreatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin: a double-blind, cross-over studyNeurology200259101573157912451200

- HappeSSauterCKloschGSaletuBZeitlhoferJGabapentin versus ropinirole in the treatment of idiopathic restless legs syndromeNeuropsychobiology2003482828614504416

- SchofferKLHendersonRDO’MaleyKO’SullivanJDNonpharmacological treatment, fludrocortisone, and domperidone for orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson’s diseaseMov Disord200722111543154917557339

- ZangagliaRMartignoniEGloriosoMMacrogol for the treatment of constipation in Parkinson’s disease. A randomized placebo-controlled studyMov Disord20072291239124417566120

- HussainIFBradyCMSwinnMJMathiasCJFowlerCJTreatment of erectile dysfunction with sildenafil citrate (Viagra) in parkinsonism due to Parkinson’s disease or multiple system atrophy with observations on orthostatic hypotensionJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200171337137411511713

- FernandezHHOkunMSRodriguezRLQuetiapine improves visual hallucinations in Parkinson disease but not through normalization of sleep architecture: results from a double-blind clinical-polysomnography studyInt J Neurosci2009119122196220519916848

- RabeyJMProkhorovTMiniovitzADobronevskyEKleinCEffect of quetiapine in psychotic Parkinson’s disease patients: a double-blind labeled study of 3 months’ durationMov Disord200722331331817034006

- ShotboltPSamuelMDavidAQuetiapine in the treatment of psychosis in Parkinson’s diseaseTher Adv Neurol Disord20103633935021179595

- EmreMTsolakiMBonuccelliUMemantine for patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet Neurol201091096997720729148

- BaronePPoeweWAlbrechtSPramipexole for the treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet Neurol20109657358020452823

- RektorovaIRektorIBaresMPramipexole and pergolide in the treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease: a national multicentre prospective randomized studyEur J Neurol200310439940612823492

- DevosDDujardinKPoirotIComparison of desipramine and citalopram treatments for depression in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studyMov Disord200823685085718311826

- MenzaMDobkinRDMarinHA controlled trial of antidepressants in patients with Parkinson disease and depressionNeurology2009721088689219092112

- EggertKOertelWHReichmannHParkinson-Syndrome: Diagnostik und TherapieLeitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der NeurologieDienerHCWeimarC Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie 5 überarb AuflageStuttgartThieme201282112 [German]

- SchuepbachWMRauJKnudsenKEARLYSTIM Study GroupNeurostimulation for Parkinson’s disease with early motor complicationsN Engl J Med20132143687610622 10.1056/NEJMoa120515823406026