Abstract

Background

Research shows that impairment in the expression and recognition of emotion exists in multiple psychiatric disorders. The objective of the current study was to evaluate the way that patients with schizophrenia and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder experience and display emotions in relation to specific emotional stimuli using the Facial Action Coding System (FACS).

Methods

Thirty individuals participated in the study, comprising 10 patients with schizophrenia, 10 with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and 10 healthy controls. All participants underwent clinical sessions to evaluate their symptoms and watched emotion-eliciting video clips while facial activity was videotaped. Congruent/incongruent feeling of emotions and facial expression in reaction to emotions were evaluated.

Results

Patients with schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder presented similarly incongruent emotive feelings and facial expressions (significantly worse than healthy participants). Correlations between the severity of psychopathological condition (in particular the severity of affective flattening) and impairment in recognition and expression of emotions were found.

Discussion

Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia seem to present a similarly relevant impairment in both experiencing and displaying of emotions; this impairment may be seen as a chronic consequence of the same neurodevelopmental origin of the two diseases. Mimic expression could be seen as a behavioral indicator of affective flattening. The FACS could be used as an objective way to evaluate clinical evolution in patients.

Introduction

The ability to identify and express emotions through facial expression is an essential component of human communication and social interaction. The manifestation of a facial expression consequent to an emotion is a complex process that involves functions different from those involved in voluntary movement of facial muscles.Citation1,Citation2 Six universal emotions have been established, including amusement, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise, each of which corresponds to a specific arrangement of facial muscles and has partially separable neurocircuitry processes.Citation3

The elaboration of facial emotions involves specific neuronal systems, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, fusiform gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, amygdale, ventral striatum, hippocampus, and dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus.Citation4,Citation5 Moreover, it is known that the right hemisphere is more involved in the expression of emotion than the left.Citation6–Citation8

The Facial Action Coding System (FACS) of Ekman and FriesenCitation9 is one of the most widely used instruments in the analysis of facial expression. It is based on an anatomical analysis of facial action through the codification of facial expression into 44 “action units.” Action units are anatomically defined, and represent the basic repertoire of human facial expressions. Using FACS, the intensity and variety of facial movements can be observed objectively. It has been repeatedly reported that psychiatric patients and especially patients with schizophrenia show characteristic facial activities,Citation10–Citation15 such as reduced levels of facial expressivity compared with healthy controls in reaction to emotional stimuli,Citation16–Citation18 during social interactions,Citation19 and/or as a result of the effects of medication.Citation20

Several studies have evaluated the facial expression of patients with schizophrenia in response to appropriate emotive stimuli using the FACS as a rating system of the emotions expressed, reporting that treatment with neuroleptics induces a deficit in the recognition and expression of emotions,Citation21 mainly related to the upper face,Citation16 and to specific emotions such as amusement, pain, anger, fear, and disgust.Citation22 Further, it was found that reduction in facial expressions in response to emotive stimuli was correlated with the presence of negative symptoms, in particular with affective flatteningCitation7,Citation23 and that there was no effect of gender with regard to facial expression in schizophrenia.Citation24 Just one study evaluated facial expressiveness in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder using FACS; Mergl et alCitation25 found that execution of adequate facial reactions to humor was abnormally slow in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and correlated with severity of symptoms.

Use of video clips to elicit specific emotions has a long history in clinical psychology and psychiatry;Citation26 Gross and Levenson systematized this issue, selecting and validating 16 films that successfully elicited amusement, anger, contentment, disgust, sadness, surprise, fear, and a neutral state.Citation27 Several studies using movie clips to elicit emotions in patients with schizophrenia have reported a diminished emotional response in comparison with healthy controls,Citation13 and just one study investigated this issue in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder.Citation25

Obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia are considered to have common neurodevelopmental origins, and comorbidity between these two disorders is quite frequent.Citation28 The objective of this study was to evaluate emotivity, expressed through facial expression, in patients with schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder in relation to specific emotional stimuli. We hypothesize that both diseases may present with significantly impaired perception and expression of emotions in comparison with healthy controls, suggesting an additional common pathological element between schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Materials and methods

Participants

The sample consisted of outpatients recruited at the A Fiorini Hospital of Terracina, Sapienza University of Rome, and healthy controls. After signing an written informed consent form, patients underwent a structured clinical interview according to the SCID-I modelCitation29 and the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. They were then divided in two groups, ie, patients suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder (n = 10) and those suffering from schizophrenia (n = 10, ). Patients with significant neurological diseases, other Axis 1 diagnoses, tardive dyskinesia, a history of abuse of alcohol or other drugs of abuse, or on treatment with typical antipsychotics were excluded from the study.

Table 1 Study participants

Study design

The first stage of this study required participants to be assessed using the following scales: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale 24-items (BPRS) for all patients, the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for patients with schizophrenia. The BPRS is a rating scale used to measure psychiatric symptoms. Each symptom is rated 1–7 and the following items are scored: somatic concern, anxiety, depression, suicidality, guilt, hostility, elevated mood, grandiosity, suspiciousness, hallucinations, unusual thought content, bizarre behavior, self-neglect, disorientation, conceptual disorganization, affective flattening, emotional withdrawal, motor retardation, tension, uncooperativeness, excitement, distractibility, motor hyperactivity, and mannerisms and posturing.Citation30

The Y-BOCS is a test to rate the severity of symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The scale is a clinician-rated, 10-item scale (obsession-free interval, interference due to obsessive thoughts, distress associated with obsessive thoughts, resistance against obsessions, degree of control over obsessive thoughts, time spent performing compulsive behaviors, interference due to compulsive behaviors, distress associated with compulsive behavior, resistance against compulsions, degree of control over compulsive behavior), each item rated from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (extreme symptoms), yielding a total possible score range from 0 to 40.Citation31

The PANSS is a scale used to assess the severity of symptoms among patients with schizophrenia. Administration takes approximately 45 minutes and patients are rated from 1 to 7 on 30 different symptoms subdivided into three subscales: positive (delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinations, hyperactivity, grandiosity, suspiciousness/persecution, hostility); negative (blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, poor rapport, passive/apathetic social withdrawal, difficulty in abstract thinking, lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation, stereotyped thinking); and general psychopathology (somatic concern, anxiety, guilt feelings, tension, mannerisms and posturing, depression, motor retardation, uncooperativeness, unusual thought content, disorientation, poor attention, lack of judgment and insight, disturbance of volition, poor impulse control, preoccupation, active social avoidance).Citation32

In a second phase (film session), all patients watched video clips designed to elicit significant and specific emotions, including amusement, fear, surprise, anger, sadness, disgust, or neutrality. The mimic reaction of each patient in response to the vision of the films was video-recorded. These video clips, all in Italian, were watched by the three groups of people in the same order, according to the protocol of Gross and Levenson:Citation27 video 1, neutral; video 2, amusement; video 3, fear; video 4, surprise; video 5, anger; video 6, sadness; video 7, disgust; and video 8, amusement (). Between video clips, patients were asked to fill out a post film questionnaire to indicate the emotion experienced in relation to the video (). Each response to the questionnaire was then scored in relation to the expected emotion.

Table 2 Video clips used to elicit emotions

Table 3 Post film questionnaire

Two different reports were produced. In the report of concordant responses, a score of 1 was given for each emotional report concordant with the expected emotion, and a score 0 was given if the patient reported not having felt any emotion (neutrality) or having felt an emotion different from that expected. Scores could range between a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 8. In the report of discordant responses, a score of 1 was given for each emotional report discordant with the expected emotion associated with the video clip and 0 if the patient reported not having felt any emotion (neutrality). Scores could range between a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 8.

At the end of the film session, the mimic reactions to the video clips were coded following the indications in the FACS investigator’s guide.Citation33 The same three examiners (EP, GV, DL) evaluated all the video registrations. The three examiners previously attended a specific three-day workshop organized by the FACS Research Center at the University of Trieste. The scoring took into account the specific emotion associated with the video expectedCitation27 and the combination of action units observed in response. Because each video was evocative of only one specific emotion,Citation27 specific combinations of action units were expected in relation to each video.Citation33 If one of the expected combinations of emotion and action units occurred, the examiners assigned a score of 1; if the expected combinations did not occur, the examiners assigned a score of 0 (this scoring was repeated for each movie clip).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) software version 17. Means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlation coefficient were used. One-way univariate analysis of variance was performed to compare the means of patients divided into diagnosis groups. Because the diagnosis factor had more than two levels, post hoc tests were calculated using the Bonferroni test.

Results

Demographics

Ten patients were enrolled in each of the three groups of participants: obsessive-compulsive disorder group (mean age 40.22 ± 13.49 years), schizophrenia group (mean age 40.88 ± 12.97 years), and healthy participants (mean age 40.20 ± 10.49 years). Each group included five males and five females (). At the time of evaluation, obsessive-compulsive disorder patients were treated with the following medications: clomipramine (n = 7), fluvoxamine (n = 4), sertraline (n = 1), escitalopram (n = 1), citalopram (n = 1), valproic acid (n = 3), gabapentin (n = 1), alprazolam (n = 3), lorazepam (n = 1), and zolpidem (n = 1). Schizophrenia patients were treated with the following medications: paliperidone (n = 3), aripiprazole (n = 4), olanzapine (n = 1), quetiapine (n = 1), clozapine (n = 1), risperidone (n = 1), valproic acid (n = 4), and lithium (n = 1).

Post film questionnaire: concordant and discordant responses

In the report of concordant responses, analysis of variance showed that the diagnosis factor influenced the total score of concordant responses in the post film questionnaire (F[2.25] = 16.413; P ≤ 0.001).

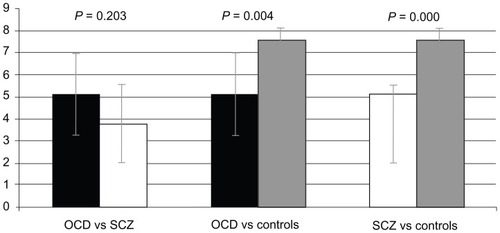

Comparing the groups between them with the post hoc Bonferroni test, our results showed that healthy controls had significantly higher scores (7.60 ± 0.516) than both obsessive-compulsive disorder patients (5.11 ± 1.833; difference of means −2.489; P = 0.004) and schizophrenia patients (3.78 ± 1.787; difference of means −3.822; P < 0.001). There was no difference in performance between patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and those with schizophrenia ().

Figure 1 Mean number of concordant responses in obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, and control groups.

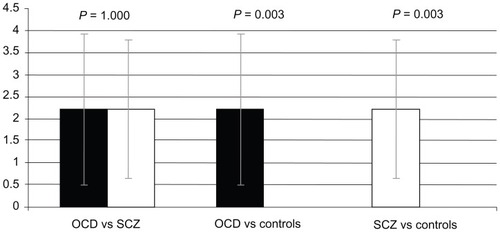

In the report of discordant responses, analysis of variance showed that the diagnosis factor influenced the total score of discordant responses in the post film questionnaire (F[2.25] = 9.205; P = 0.001). Post hoc comparisons indicated that the number of discordant responses in the healthy participant group (0 ± 0) was significantly lower than for patients with either obsessive-compulsive disorder (2.222 ± 1.716; difference of means −2.222; P = 0.003) or schizophrenia (2.222 ± 1.563; difference of means −2.222; P = 0.003). No statistically significant difference was found between patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and those with schizophrenia ().

Facial expression

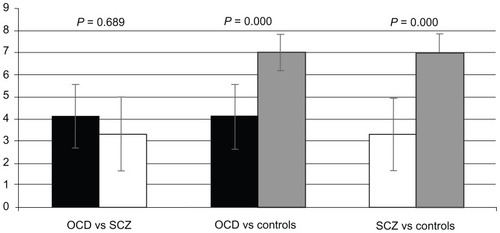

Analysis of variance indicates that the “diagnosis” factor influenced the number of film-elicited emotions correctly expressed on the face (F[2.25] = 19.991; P < 0.001). FACS scores for healthy participants were significantly higher (7 ± 0.816) than in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (4.11 ± 1.453; difference of means −2.889; P < 0.001) or schizophrenia (3.33 ± 1.658; difference of means −3.667; P < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and those with schizophrenia. No significant difference was found between patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and those with schizophrenia ().

Correlation between Y-BOCS, FACS, and post film questionnaire scores in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder

A statistically significant positive correlation was found between FACS score and concordant responses (r = 746; P = 0.021). Statistically significant negative correlations were found between discordant responses and concordant responses (r = −0.883; P = 0.002) and between discordant responses and FACS scores (r = 0.713; P = 0.031). Negative correlations approaching statistical significance were found between Y-BOCS and FACS scores (r = −0.657; P = 0.054) and between Y-BOCS scores and concordant responses (r = −0.659; P = 0.053). The positive correlation between Y-BOCS scores and discordant responses was not significant (r = 0.550; P = 0.125, ).

Table 4 Correlation between Y-BOCS scores, FACS scores and post film questionnaire in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder

Correlation between PANSS, FACS, and post film questionnaire in patients with schizophrenia

The only significant correlation was found between PANSS total score and the negative PANSS subscale score (r = 0.787; P = 0.012). Among the others, the strongest positive correlations were found between discordant responses and the negative PANSS subscale score (r = 0.412) and the strongest negative correlation was found between FACS and PANSS total score (r = −0.369, ).

Table 5 Correlation between PANSS scores, FACS scores, and post film questionnaire in schizophrenia patients

Correlation between BPRS, FACS, and post film questionnaire

In the overall sample, there were significant positive correlations between BPRS total score and the BPRS affective flattening item (r = 0.697; P = 0.001) and between the number of concordant responses and FACS total score (r = 0.779; P < 0.001); significant negative correlations were found between FACS total score and BPRS total score (r = −0.469; P = 0.049) and between the BPRS affective flattening item and number of concordant responses (r = −0.487; P = 0.040). In the obsessive-compulsive disorder group, significant positive correlations were found between BPRS total score and the BPRS affective flattening item (r = 0.707; P = 0.033) and between the number of concordant responses and FACS total score (r = 0.746; P = 0.021); significant negative correlations were found between the BPRS affective flattening item and FACS total score (r = −0.732; P = 0.025), between the number of concordant responses and number of discordant responses (r = −0.883; P = 0.002), and between FACS total score and number of discordant responses (r = −0.713; P = 0.031). No statistically significant correlations were found in the schizophrenia group ().

Table 6 Correlation between BPRS scores, FACS scores, and post film questionnaire

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating and comparing facial expressions in patients with schizophrenia and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder using the FACS system. As expected, the healthy controls showed more appropriate experience of emotion and facial expression than patients with schizophrenia and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder. It is known that patients with schizophrenia are impaired in their ability to discriminate and recognize emotions expressed by others, have difficulty in expressing their own emotional states, and show a marked deficiency in facial expression that may be correlated with length and type of pharmacological treatment.Citation13

Doop et al showed that worse social functioning is correlated with errors in recognition of emotional expressions on the face, and that patients with schizophrenia show general deficits in processing of emotional expressions which, in turn, are associated with worse symptoms and reduced social functioning.Citation34 However, an emotion subjectively or objectively “experienced” by patients may be different from the emotion “recognized” by patients. For instance, a patient may recognize that a video is happy, but due to his/her affective psychopathology, experience sadness.

The results obtained by administration of the post film questionnaire showed that patients with schizophrenia and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder showed fewer concordant responses compared with healthy people (). It is interesting to note that there was no significant difference between the results for patients with schizophrenia and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder (), indicating that patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder have an impairment almost identical to that in patients with schizophrenia with regard to experiencing emotions, even though this kind of impairment is usually considered a classical phenomenon related to schizophrenia and not to obsessive-compulsive disorder.Citation35,Citation36

This finding is strengthened by the scoring of facial activity in response to video clips eliciting emotion, ie, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder showed mimic emotional responses very similar to those in patients with schizophrenia, and the scores for the two groups did not differ significantly (). These findings indicate that patients with schizophrenia and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder seem to suffer from similar impairments with regard to both experiencing and expressing emotions.

This common feature increases the number of characteristics shared between the two diseases. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia are, in fact, considered to be neurodevelopmental disorders with dysfunctional frontal subcortical circuitry.Citation37 A possible common neurodevelopmental origin is suggested by several lines of evidence: both obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia have a juvenile onset and chronic course; relevant neurological soft signs are present in both diseases;Citation38,Citation39 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and those with schizophrenia have more adverse perinatal experiences than healthy controls;Citation38,Citation40 obsessive-compulsive symptoms are clinically important phenomena in people with schizophrenia; and people with obsessive-compulsive disorder often experience psychosis.Citation41 In line with this theory, the impaired capacity to experience and express emotions may be seen as another chronic consequence of the same neurodevelopmental origin of the two diseases.

The hypothesized common neurodevelopmental origin of impaired expression and experience of emotions in obsessive-compulsive disorder and schizophrenia is also supported by the fact that this kind of impairment is less frequent and less relevant in psychiatric patients affected by diseases with a different presumed etiopathogenesis. For example, it is known that patients with bipolar disorderCitation42 or unipolar depressionCitation16 are more accurate in recognizing emotions than patients with schizophrenia.

This study revealed an important correlation in the overall sample of patients between affective flattening, incongruent answers to a post film questionnaire, and low FACS scores (), leading to the idea that mimic expression is a behavioral indicator of affective flattening,Citation18 which is considered to be the most important negative symptom of schizophrenia, even if not pathognomic of the disease. Controversy surrounds the issue of whether second-generation antipsychotics are more effective than first-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of negative symptoms. However, it is undisputed that negative symptoms persist in many cases despite pharmacological treatment.Citation43–Citation45 Negative symptoms are known to be strongly connected with neurogenesis, and thus present in both schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder: Flagstad et alCitation46 recently found that disruption of neurogenesis in the rat led to behavioral changes that mimic the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

The results of this study also show a correlation between the severity of psychopathology and impaired ability to feel, express, and communicate emotions. A more severe psychopathological condition (measured on the BPRS scale) correlated with poorer facial expressiveness in the overall sample of patients, and more severe obsessive-compulsive symptoms (measured on the Y-BOCS scale) correlated with a minor number of concordant responses and with inappropriate mimic expression in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. These data partially confirm the results of previous studiesCitation13 and highlight the fact that the FACS system could be used as a reliable semi-objective method to evaluate the clinical course in patients.

The small number of participants is a major limitation of this study and, for this reason, the results can only be considered preliminary. The choice to reduce the power of FACS to a binary number (expression prototype present or absent) makes it a less sensitive measure and, as such, different degrees of more refined and subtle facial movements could not be evaluated. However, this step was deemed necessary because it reduced the possibility of codification bias. Further studies are needed to assess further the differences and similarities between emotional responses in obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, and other psychiatric disease.

Disclosure

The authors of this paper report no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties. All authors acknowledge that the conflict of interest disclosures are complete for both themselves and their coauthors, to the best of their knowledge.

References

- Duchenne de BoulogneGBThe Mechanism of Human Facial ExpressionNew York, NYCambridge University Press1990

- SchilbachLEickhoffSBMojzischAVogeleyKWhat’s in a smile? Neural correlates of facial embodiment during social interactionSoc Neurosci20083375018633845

- GosselinPKirouacGDecoding facial emotional prototypesCan J Exp Psychol1995493133299264759

- KohlerCTurnerTBilkerWFacial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: intensity effects and error patternAm J Psychiatry20031601768177414514489

- LawrenceNWilliamsASurguladzeSSubcortical and ventral prefrontal cortical neural responses to facial expressions distinguish patients with bipolar disorder and major depressionBiol Psychiatry20045557858715013826

- BrockmeierBUlrichGAsymmetries of expressive facial movements during experimentally induced positive versus negative mood states: a videoanalytic studyCogn Emot19937393405

- BorodJCAlpertMBrozgoldAA preliminary comparison of flat affect schizophrenics and brain-damaged patients on measures of affective processingJ Commun Disord198922931042723147

- AdelmannPZajoncRFacial efference and the experience of emotionAnnu Rev Psychol1989402492802648977

- EkmanPFriesenWVFacial Action Coding System: A Technique for the Measurement of Facial MovementPalo Alto, CAConsulting Psychologists Press1978

- EdwardsJJacksonHJPattisonPEEmotion recognition via facial expression and affective prosody in schizophrenia: a methodological reviewClin Psychol Rev20022278983212214327

- KrauseRSteimerESanger-AltCWagnerGFacial expression of schizophrenic patients and their interaction partnersPsychiatry1989521122928411

- Myin-GermeysIDelespaulPAde VriesMWSchizophrenia patients are more emotionally active than is assumed based on their behaviorSchizophr Bull20002684785411087017

- PolliEBersaniFSDe RoseCFacial Action Coding System (FACS): an instrument for the objective evaluation of facial expression and its potential applications to the study of schizophreniaRiv Psichiatr201247126138 Italian22622249

- SchaeferKLBaumannJRichBAPerception of facial emotion in adults with bipolar or unipolar depression and controlsJ Psychiatr Res2010441229123520510425

- SchneiderFFusIFriedrichJHeimannHHimerWMobility of mimic in unmedicated schizophrenic patientsZeitschrift fuer Klinische Psychologie199221352360 German

- GaebelWWolwerWFacial expressivity in the course of schizophrenia and depressionEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci200425433534215365710

- FalkenbergIBartelsMWildBKeep smiling! Facial reactions to emotional stimuli and their relationship to emotional contagion in patients with schizophreniaEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci200825824525318297418

- EllgringHGaebelWFacial expression in schizophrenic patientsBeigelALopez IborJJCosta e SilvaJAPast, Present, and Future of PsychiatryLondon, UKWorld Scientific19951

- AghevliMABlanchardJJHoranWPThe expression and experience of emotion in schizophrenia: a study of social interactionsPsychiatry Res200311926127012914897

- DworkinRClarkSAmadorXGormanJDoes affective blunting in schizophrenia reflect affective deficit or neuromotor dysfunctionSchizophr Res1996203013068827857

- SchneiderFEllgringHFriedrichJThe effects of neuroleptics on facial action in schizophrenic patientsPharmacopsychiatry1992252332391357682

- KohlerCGMartinEAStolarNStatic posed and evoked facial expressions of emotions in schizophreniaSchizophr Res2008105496018789845

- BlanchardJJSayersSLCollinsLMBellackASAffectivity in the problem solving interactions of schizophrenia patients and their family membersSchizophr Res20046910511715145476

- SimonsGEllgringJHBeck-DosslerKGaebelWWölwerWFacial expression in male and female schizophrenia patientsEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci201026026727619816738

- MerglRVogelMMavrogiorgouPKinematical analysis of emotionally induced facial expressions in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorderPsychol Med2003331453146214672254

- PhilippotPInducing and assessing differentiated emotion-feeling states in the laboratoryCogn Emot19937171193

- GrossJJLevensonRWEmotion elicitation using filmsCogn Emot1995987108

- BuckleyPFMillerBJLehrerDSCastleDJPsychiatric comorbidities and schizophreniaSchizophr Bull20093538340219011234

- FirstMBSpitzerRLGibbonMWilliamsJBStructured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient EditionNew York, NYBiometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute2002

- OverallJEGorhamDRThe Brief Psychiatric Rating ScalePsychol Rep196210799812

- GoodmanWKPriceLHRasmussenSAThe Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliabilityArch Gen Psychiatry198946100610112684084

- KaySRFiszbeinAOplerLAThe Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophreniaSchizophr Bull1987132612763616518

- EkmanPFriesenWHagerJCFacial Action Coding System Investigator’s GuidePalo Alto, CAConsulting Psychologists Press1978

- DoopMLParkSFacial expression and face orientation processing in schizophreniaPsychiatry Res200917010310719896209

- BozikasVPKosmidisMHGiannakouMSaitisMFokasKGaryfallosGEmotion perception in obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Int Neuropsychol Soc20091514815319128539

- AignerMSachsGBruckmüllerECognitive and emotion recognition deficits in obsessive-compulsive disorderPsychiatry Res200714912112817123634

- ThomasNTharyanPSoft neurological signs in drug-free people with schizophrenia with and without obsessive-compulsive symptomsJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci201123687321304141

- BersaniGClementeRGherardelliSBersaniFSManualiGObstetric complications and neurological soft signs in male patients with schizophreniaActa Neuropsychiatr2012246344348

- GuzHAygunDNeurological soft signs in obsessive-compulsive disorderNeurol India200452727515069243

- GellerDAWielandNCareyKPerinatal factors affecting expression of obsessive compulsive disorder in children and adolescentsJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol20081837337918759647

- AttademoLDe GiorgioGQuartesanRMorettiPSchizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder: from comorbidity to schizo-obsessive disorderRiv Psichiatr20124710611522622247

- RoccaCCHeuvelECaetanoSCLaferBFacial emotion recognition in bipolar disorder: a critical reviewRev Bras Psiquiatr20093117118019578691

- BersaniFSCapraEMinichinoAFactors affecting interindividual differences in clozapine response: a review and case reportHum Psychopharmacol20112617718721455971

- BuchananRWJavittDCMarderSRThe Cognitive and Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia Trial (CONSIST): the efficacy of glutamatergic agents for negative symptoms and cognitive impairmentAm J Psychiatry20071641593160217898352

- LibermanJStroupTMcEvoyJClinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) investigators: effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophreniaN Engl J Med20053531209122316172203

- FlagstadPGlenthøjBYDidriksenMCognitive deficits caused by late gestational disruption of neurogenesis in rats: a preclinical model of schizophreniaNeuropsychopharmacology20053025026015578007