Abstract

Objectives

This review aimed to identify the evidence for predictors of repetition of suicide attempts, and more specifically for subsequent completed suicide.

Methods

We conducted a literature search of PubMed and Embase between January 1, 1991 and December 31, 2009, and we excluded studies investigating only special populations (eg, male and female only, children and adolescents, elderly, a specific psychiatric disorder) and studies with sample size fewer than 50 patients.

Results

The strongest predictor of a repeated attempt is a previous attempt, followed by being a victim of sexual abuse, poor global functioning, having a psychiatric disorder, being on psychiatric treatment, depression, anxiety, and alcohol abuse or dependence. For other variables examined (Caucasian ethnicity, having a criminal record, having any mood disorders, bad family environment, and impulsivity) there are indications for a putative correlation as well. For completed suicide, the strongest predictors are older age, suicide ideation, and history of suicide attempt. Living alone, male sex, and alcohol abuse are weakly predictive with a positive correlation (but sustained by very scarce data) for poor impulsivity and a somatic diagnosis.

Conclusion

It is difficult to find predictors for repetition of nonfatal suicide attempts, and even more difficult to identify predictors of completed suicide. Suicide ideation and alcohol or substance abuse/dependence, which are, along with depression, the most consistent predictors for initial nonfatal attempt and suicide, are not consistently reported to be very strong predictors for nonfatal repetition.

Introduction

In recent years, suicide-attempt (SA) rates have been widely studied. A World Health Organization community survey reported the lifetime prevalence of SAs at 0.4%–4.2%.Citation1 Female sex, young age, marital status (divorced or widowed), and having a personality disorder have been associated with an increased risk of attempting suicide.

The incidence rate for completed suicide (S) is 11.2/100,000,Citation2 increases with age, and is three times higher in males than in females.Citation3 Suicide accounts for about 1% of all deaths and is the ninth-leading cause of death in the US and the third in ages 15–24 years.Citation3,Citation4 Rates in Caucasians are twice those of non-Caucasian populations, and married people are less likely than single, divorced, or widowed to commit suicide.Citation2 For those in bereavement, the risk is higher in the first year after loss. Rates are higher in Protestants (31.4/100,000) than in Catholics (10.9/100,000) or Jews (15.5/100,000). Unemployment increases the rate of suicide by 50%.Citation3

The suicide risk is higher in psychiatric patients compared to nonpsychiatric populations. More specifically, lifetime risk of suicide has been reported as high as 15% for affective disorders, 10% for schizophrenia, and 2%–3% for alcohol abuse.Citation4 With respect to affective disorders, the risk is higher with increasing severity of depression. Suicides occur more often in patients with a family history of suicide, mood disorders, and alcohol abuse.Citation4 Suicidality tends to emerge early in the course of a mood disorder, and increases in association with melancholia and agitation.Citation4

Despite these many variables having been associated with suicidal behavior, their usefulness in predicting future suicidal behavior remains undemonstrated. The prospective prediction of later suicide remains difficult.Citation5,Citation6 A need exists, as underlined by Hughes and Owens,Citation6 for more effective monitoring of people who contact hospitals because of SAs, and for more information on patients who carry out SAs but do not attend hospital. The likelihood of a repeated attempt after a first SA has been investigated less extensively. An episode of self-harm is a strong predictor of later suicide, with the risk peaking in the first 6 months after a self-harming episode, but risk persists for many decades.

A recent review estimated the 1-year incidence of repetition at 16% and fatal repetition at 2% of attempters.Citation7 After 9 years, the suicide-fatality rate increased to more than 5%. Both fatal and nonfatal repetition rates were reported to be lower in Mediterranean than in Northern European countries.Citation8

However, despite the potential importance of studies investigating the risk factors involved in repetition of SA, no systematic reviews of the issue have been reported. Accordingly, the aim of this review was to identify the evidence for predictors of repetition of SA, and more specifically for subsequent S.

Methods

One of the authors (MB) searched both PubMed and Embase systematically for studies carried out between January 1, 1991 and 31 December, 2009 in English, using the keywords repetition/repeated suicide attempt, repetition/repeated self-harm, recurrence/recurrent self-harm, recurrence/recurrent suicide attempt, repetition/repeated self-poisoning, and recurrence/recurrent self-poisoning. Suicides in most primary studies included those that were definite (by verdict of a coroner or equivalent authority) or probable (open verdict or equivalent judgment); definitions were too variable for us to discriminate further, and we have included them all and used this broad definition of suicide. With the terms “suicide attempt” or “SA,” any nonfatal act in which the patient causes self-harm (self-mutilation, poisoning, jumping from high places, firearm shots, hanging, asphyxiation) was considered. The nomenclature has been taken from Silverman et al; we considered all suicidal acts, despite the degree of suicidal intent. With the term “SA” we mean a not-completed suicide (with or without injuries), while with the term “S” we mean a completed suicide.Citation9,Citation10

For the aim of this study, we included cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies. Since our review focused on environmental risk factors and not on management, we excluded studies investigating self-harm management and/or care. Moreover, some of these studies investigated selected populations at risk, and others had very small samples. Thus, we decided to exclude studies investigating selected populations (childhood/adolescence, elderly, males/females only, minorities only, patients with a specific personality disorder), studies with small samples (fewer than 50), or prospective studies with a follow-up shorter than 6 months. We decided to exclude special populations because the aim of the review was the prospective prediction of later suicide in the whole population referring to the emergency room.

Studies on self-poisoning only were included because the self-poisoning method encompasses 80% of females’ and 64% of males’ SAs.Citation8 For the same reason, we decided to include studies on adults only.

Data extraction

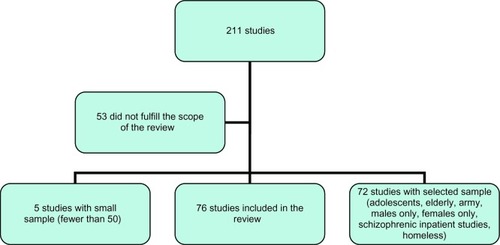

After a first screening, 211 papers satisfied our inclusion criteria. Six were useful for the introduction and for the discussion. The majority of them were carried out in Europe. Since designs, the variables studied, and the length of follow-up were different among these studies, a formal meta-analysis or direct comparison was not possible. After excluding 53 studies for not fulfilling the scope of the review, five studies for small sample size, 72 studies for a selected sample (37 childhood/adolescence, ten elderly, three females only, one males only, 19 patients with a psychiatric diagnosis, two minorities), we were left with 76 studies: 13 (17%) with a cohort analysis, 45 (59%) with a case-control analysis, and 18 (24%) with a cross-sectional analysis ().

Sixty of them (79%) were carried out in Europe, more specifically, 24 in the UK, 20 in Scandinavian countries, five in Ireland, two in France, one in Spain, one in the Netherlands, one in Belgium, and six in three or more countries. The other studies were done in the US (five), Australia (four), Canada (two), the People’s Republic of China (two), Iran (one), Brazil (one), and Uganda (one). SA was investigated in 64, while S was investigated in 18 studies.

All the risk factors investigated in the studies were inserted and then selected by a consensus-based process (by all the authors).

Results

Nonfatal repetition

The strongest predictor for nonfatal repetition was a history of SA, a finding reported as significant in 13 of 16 multivariate analyses and 13 of 14 univariate analyses (). Also significant were being a victim of a sexual abuse (multivariate 5/9, univariate 4/5), poor global functioning (multivariate 3/4, univariate 4/4), having a psychiatric disorder (multivariate 5/11, univariate 6/11), undergoing psychiatric treatment (multivariate 2/7, univariate 7/8), depression (multivariate 3/10, univariate 8/12), anxiety (multivariate 2/6, univariate 4/5), or alcohol abuse or dependence (multivariate 4/10, univariate 4/8). There were weaker associations for having a personality disorder, repetition for young adult age, unmarried status, alcohol abuse or dependence, psychiatric morbidity or treatment, and unemployment status. For many variables (Caucasian ethnicity, having a criminal record, having any mood disorders, bad family environment, and impulsivity) there are indications for a correlation, but data are very scarce. The results of analyses are in .

Table 1 Summary of available factors correlated with suicidality

Completed suicide

The strongest predictors of S are older age (multivariate 9/16, univariate 2/5), a high suicide ideation (multivariate 5/9, univariate 1/2), a history of SA (multivariate 7/11, univariate 1/5). Living alone, male sex, and alcohol abuse are weaker predictors. There is a correlation (but supported by very scarce data) for poor impulsivity and having a somatic diagnosis. There are no data available for sexual and physical abuse during childhood or for the family environment. The syntheses of the available results are in .

Table 2 Factors correlated with suicide attempts (SAs) and completed suicide (S)

Discussion

At present, there is no psychological test, clinical technique, or biological marker sensitive and specific enough to predict either short-term suicide or repetition. In line with Appleby et al,Citation3 there is a north–south gradient in the repetition rate of suicide. A study by PokornyCitation5 illustrates how a method to predict suicide based on recognized risk factors will not only lead to a better identification of individuals at risk but also to a higher number of lost-to-follow-up or undetected cases. In this study, the authors attempted to identify which of 4,800 consecutive patients would commit suicide. On the basis of 21 risk factors, they identified 803 patients having increased risk of suicide. Thirty of 803 (3.7%) committed suicide in a 5-year follow-up. None of these risk factors was detected in 37/67 suicides. These results are confirmed by a review of twelve studies conducted by Diekstra in 1985.Citation85 About 50% of suicidal people had committed at least one previous attempt. Also in this review, it is shown that it is easier to detect a nonfatal SA than a fatal one. This means that S is multifactorial, and involves not only medical but also philosophical aspects, eg, life is or is not worth living, and it is often a difficult but aware choice. The goal of a suicide assessment is not to predict suicide, but to place a person along a putative risk continuum to evaluate suicidality, especially in the period immediately following the attempt, and allow for a more informed intervention. In fact, according to Reulbach and Bleich,Citation86 up to 45% of people who deliberately harm themselves leave accident and emergency departments without receiving an adequate psychiatric assessment; after the discharge, the patients should not be lost in aftercare, especially if they suffer from depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia.Citation86

In fact, after adjustment for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and hospital differences, being referred for specialist follow-up was associated with reduction in repetition rate.Citation87

Synthesis of the available results

It is difficult to identify risk factors for repetition of nonfatal SA, and even more for repetition ending in S. The studies evaluated in this review had different designs and follow-up, so they are not comparable for a systematic review with meta-analysis of the available data. However, some intriguing results are available. Alcohol/substance abuse or dependence and suicide ideation, which are, along with depressed mood, the most consistent predictors for self-harm and suicide,Citation4 do not seem as strong for nonfatal repetition. The presence of a previous SA is a more consistent finding for nonfatal repetition than for S, but it is the best risk factor for both and persists for many decades. The presence of a personality disorder, depression, sexual abuse in childhood, alcohol dependence, or unemployed or unmarried status are more consistently significant in nonfatal than in fatal SAs, while in nonrepeated SA, having a personality disorder increased rates among both fatal and nonfatal attempts.Citation4 Impulsivity seems to be correlated with SA and inversely correlated with suicide completion. On the other hand, having a suicide ideation, (older) age, and (male) sex are thought to be more consistently found in fatal repetition, although the role of sex is not very clear. Female sex and younger age, in contrast with data on nonfatal SA, are not likely to predict repetition. This means that once a first SA has been made (an event more frequent in females and younger people), the risk for a second attempt does not appear increased in these two categories.

Other variables, such as family environment, problem-solving, and global functioning, have a positive correlation with fatal and/or nonfatal SA repetition, but data available are not sufficient to identify them as “predictors” of repetition. Further studies are needed to confirm this correlation.

Methodological pitfalls

Many other variables have been studied, eg, Caucasians commit suicide twice as frequently as other races, and Protestants are more likely to commit suicide than Catholics or Jews.Citation4 A nonheterosexual orientation carries an increased risk for attempted but not for completed SAs.Citation4 In all these cases, data on SA repetition are inconsistently reported.

Moreover, since a previous SA is the best risk factor for both fatal and nonfatal repetition, most findings presented here might not be specific to repetition. Only three studies in our group investigated the risk factors in first attempters for future attempts,Citation38,Citation45,Citation78 and only oneCitation45 studied it prospectively.

According to Owens et al,Citation7 the median proportion of patients repeating nonfatal SA is 16% at 1 year and 23% in studies lasting longer than 4 years. For a subsequent suicide, after a longer follow-up, the suicide rate increases from less than 2% at 1 year to more than 5% in studies lasting over 9 years. However, as most prospective studies lasted 1 year, the risk factors for S in subsequent years may differ from those detected at early follow-up.

Future perspectives

Further studies would ideally examine a well-defined inception cohort (ie, patients at time of first SA) identified and followed prospectively. A long-term follow-up (at least 4 years) is recommended. Standard definitions of risk and prognostic factors should be determined when planning the study. Interacting factors such as previous attempts or selected samples should be controlled for at the planning or the analysis stage. Some variables, like sexual child abuse, family environment, problem-solving, and global functioning, should be included, to evaluate their role for a repeated episode. Ideally, a study would compare different ethnicities and religions and investigate the differences in suicide repetition between immigrants and nonimmigrants. Sexual orientation should be investigated as well.

Conclusion

SA repetition (whether fatal or nonfatal) is a common event in developed countries. Prediction of recurrent SA in a patient who committed a first SA is an important task for the psychiatrist. However, it is hard to find independent predictors out of all the many variables associated with repeated and especially with S. Based on the available evidence, only a previous SA, depression, sexual abuse in childhood, and personality disorders have been found to predict nonfatal SA, while previous SA and older age were found to predict fatal SA. Suicidal ideation, which is one of the most consistent predictors for SA and S, does not seem as strong for repeated SA, while it remains consistent for S. In several cases, no apparent risk factor was detected, and it makes it difficult to prevent fatal and nonfatal attempts.

A large multicenter prospective investigation of first SAs should be undertaken comparing different countries and differing social and cultural backgrounds and settings within each country.

Acknowledgments

Jennifer Covino, PhD and Countney Clabby, PhD, for their help on the data collection, and Ettore Beghi, MD, for critically reviewing the study proposal.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BertoloteJMFleischmannADe LeoDSuicide attempts, plans, and ideation in culturally diverse sites: the WHO SUPRE-MISS community surveyPsychol Med200535101457146516164769

- MościckiEKIdentification of suicide risk factors using epidemiologic studiesPsychiatr Clin North Am19972034995179323310

- ApplebyLDennehyJAThomasCSFaragherEBLewisGAftercare and clinical characteristics of people with mental illness who commit suicide: a case-control studyLancet199935391621397140010227220

- BlumenthalSJKupferDJSuicide over the Life Cycle: Risk Factors, Assessment, and Treatment of Suicidal PatientsWashingtonAmerican Psychiatric Association1990

- PokornyADPrediction of suicide in psychiatric patients. Report of a prospective studyArch Gen Psychiatry19834032492576830404

- HughesTOwensDCan attempted suicide (deliberate self-harm) be anticipated or prevented?Curr Opin Psychiatry1995827679

- OwensDHorrocksJHouseAFatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic reviewBr J Psychiatry200218119319912204922

- SchmidtkeABille-BraheUDeLeoDAttempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989–1992. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on ParasuicideActa Psychiatr Scand19969353273388792901

- SilvermanMMBermanALSanddalNDO’CarrollPWJoinerTERebuilding the tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 1: Background, rationale and methodologySuicide Life Threat Behav200737324826317579538

- SilvermanMMBermanALSanddalNDO’CarrollPWJoinerTERebuilding the tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: Suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviorsSuicide Life Threat Behav200737326427717579539

- AsnisGMFriedmanTASandersonWCKaplanMLvan PraagHMHarkavy-FriedmanJMSuicidal behaviors in adult psychiatric outpatients, I: Description and prevalenceAm J Psychiatry199315011081128417551

- BattAEudierFLe VaouPRepetition of parasuicide: risk factors in general hospital referred patientsJ Ment Health199873285297

- Bille-BraheUJessenGRepeated suicidal behavior: a two-year follow-upCrisis199415277827988169

- BoyesAPRepetition of overdose: a retrospective 5-year studyJ Adv Nurs19942034624687963051

- BrådvikLSuicide after suicide attempt in severe depression: a long-term follow-upSuicide Life Threat Behav200333438138814695053

- BrezoJParisJHébertMVitaroFTremblayRTureckiGBroad and narrow personality traits as markers of one-time and repeated suicide attempts: a population-based studyBMC Psychiatry200881518325111

- CarterGLWhyteIMBallKRepetition of deliberate self-poisoning in an Australian hospital-treated populationMed J Aust1999170730731110327971

- CarterGLCloverKABryantJLWhyteIMCan the Edinburgh Risk of Repetition Scale predict repetition of deliberate self-poisoning in an Australian clinical setting?Suicide Life Threat Behav200232323023912374470

- CarterGReithDMWhyteIMMcPhersonMRepeated self-poisoning: increasing severity of self-harm as a predictor of subsequent suicideBr J Psychiatry200518625325715738507

- CederekeMOjehagenAPrediction of repeated parasuicide after 1–12 monthsEur Psychiatry200520210110915797693

- ChandrasekaranRGnanaselaneJPredictors of repeat suicidal attempts after first-ever attempt: a two-year follow-up studyHong Kong J Psychiatry2008184131135

- ChristiansenEJensenBFRisk of repetition of suicide attempt, suicide or all deaths after an episode of attempted suicide: a register-based survival analysisAust N Z J Psychiatry200741325726517464707

- CoakleyFHayesCFennellJJohnsonZA study of deliberate self-poisoning in a Dublin Hospital 1986–1990Ir J Psychol Med19941127072

- ColmanINewmanSCSchopflocherDBlandRCDyckRJA multivariate study of predictors of repeat parasuicideActa Psychiatr Scand2004109430631215008805

- ConnerKRPhillipsMRMeldrumSCPredictors of low-intent and high-intent suicide attempts in rural ChinaAm J Public Health200797101842184617395838

- CooperJKapurNWebbRSuicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort studyAm J Psychiatry2005162229730315677594

- CooperJHusainNWebbRSelf-harm in the UK: differences between South Asians and Whites in rates, characteristics, provision of service and repetitionSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol2006411078278816838089

- CorcoranPKeeleyHSO’SullivanMPerryIJThe incidence and repetition of attempted suicide in IrelandEur J Public Health2004141192315080385

- CraneCWilliamsJMHawtonKThe association between life events and suicide intent in self-poisoners with and without a history of deliberate self-harm: a preliminary studySuicide Life Threat Behav200737436737817896878

- da Silva CaisCFStefanelloSFabrício MauroMLVaz Scavacini de FreitasGBotegaNJFactors associated with repeated suicide attempts. Preliminary results of the WHO Multisite Intervention Study on Suicidal Behavior (SUPRE-MISS) from Campinas, BrazilCrisis2009302737819525165

- De MooreGMRobertsonARSuicide in the 18 years after deliberate self-harm: a prospective studyBr J Psychiatry199616944894948894201

- EkebergOEllingsenOJacobsenDSuicide and other causes of death in a five-year follow-up of patients treated for self-poisoning in OsloActa Psychiatr Scand19918364324371882694

- EvansJPlattsHLiebenauAImpulsiveness and deliberate self-harm: a comparison of “first-timers” and “repeaters”Acta Psychiatr Scand19969353783808792908

- EvansJReevesBPlattHImpulsiveness, serotonin genes and repetition of deliberate self-harm (DSH)Psychol Med20003061327133411097073

- FormanEMBerkMSHenriquesGRBrownGKBeckATHistory of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioral marker of severe psychopathologyAm J Psychiatry2004161343744314992968

- GilbodySHouseAOwensDThe early repetition of deliberate self harmJ R Coll Physicians Lond19973121711729131517

- HarrissLHawtonKZahlDValue of measuring suicidal intent in the assessment of people attending hospital following self-poisoning or self-injuryBr J Psychiatry2005186606615630125

- HaukkaJSuominenKPartonenTDeterminants and outcomes of serious attempted suicide: a nationwide study in Finland, 1996–2003Am J Epidemiol2008167101155116318343881

- HawCHawtonKHoustonKTownsendECorrelates of relative lethality and suicidal intent among deliberate self-harm patientsSuicide Life Threat Behav200333435336414695050

- HawCBergenHCaseyDHawtonKRepetition of deliberate self-harm: a study of the characteristics and subsequent deaths in patients presenting to a general hospital according to extent of repetitionSuicide Life Threat Behav200737437939617896879

- HawtonKHoustonKHawCTownsendEHarrissLComorbidity of axis I and axis II disorders in patients who attempted suicideAm J Psychiatry200316081494150012900313

- HenriquesGWenzelABrownGKBeckATSuicide attempters’ reaction to survival as a risk factor for eventual suicideAm J Psychiatry2005162112180218216263863

- HeyerdahlFBjornaasMADahlRRepetition of acute poisoning in Oslo: 1-year prospective studyBr J Psychiatry20091941737919118331

- HjelmelandHStilesTCBille-BraheUParasuicide: the value of suicidal intent and various motives as predictors of future suicidal behaviorArch Suicide Res199843209225

- HjelmelandHPolitCRepetition of parasuicide: a predictive studySuicide Life Threat Behav19962643954049014269

- JohnstonACooperJWebbRKapurNIndividual- and area-level predictors of self-harm repetitionBr J Psychiatry200618941642117077431

- KapurNCooperJKing-HeleSThe repetition of suicidal behavior: a multicenter cohort studyJ Clin Psychiatry200667101599160917107253

- KeeleyHO’SullivanMCorcoranPBackground stressors and deliberate self-harm. Prospective case note study in southern IrelandPsychiatr Bull R Coll Psychiatr20032711411415

- KinyandaEHjelmelandHMusisiSKigoziFWalugembeJRepetition of deliberate self-harm as seen in UgandaArch Suicide Res20059433334416179329

- KiankhooyACrookesBPrivetteAOslerTSartorelliKFait accompli: suicide in a rural trauma settingJ Trauma200967236637119667891

- LilleyROwensDHorrocksJHospital care and repetition following self-harm: multicentre comparison of self-poisoning and self-injuryBr J Psychiatry2008192644044518515895

- McAuliffeCCorcoranPKeeleyHSProblem-solving ability and repetition of deliberate self-harm: a multicentre studyPsychol Med2006361455516194285

- McAuliffeCArensmanEKeeleyHSCorcoranPFitzgeraldAPMotives and suicide intent underlying hospital treated deliberate self-harm and their association with repetitionSuicide Life Threat Behav200737439740817896880

- McAuliffeCCorcoranPHickeyPMcLeaveyBCOptional thinking ability among hospital-treated deliberate self-harm patients: a 1-year follow-up studyBr J Clin Psychol200847Pt 1435817681111

- McEvedyCJTrends in self-poisoning: admissions to a central London hospital, 1991–1994J R Soc Med19979094964989370985

- NeelemanJWesselySWadsworthMPredictors of suicide, accidental death, and premature natural death in a general-population birth cohortLancet1998351909693979439493

- NordentoftMBreumLMunckLKNordestgaardAGHundingALaursen BjaeldagerPAHigh mortality by natural and unnatural causes: a 10 year follow up study of patients admitted to a poisoning treatment centre after suicide attemptsBMJ19933066893163716418324430

- NordströmPSamuelssonMAsbergMSurvival analysis of suicide risk after attempted suicideActa Psychiatr Scand19959153363407639090

- OjehagenARegnéllGTräskman-BendzLDeliberate self-poisoning: repeaters and nonrepeaters admitted to an intensive care unitActa Psychiatr Scand19918432662711950627

- OstamoALönnqvistJExcess mortality of suicide attemptersSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol2001361293511320805

- OsváthPKelemenGErdösMBVörösVFeketeSThe main factors of repetition: review of some results of the Pecs Center in the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Suicidal BehaviourCrisis200324415115415509139

- OwensDDennisMJonesSDoveADaveSSelf-poisoning patients discharged from accident and emergency: risk factors and outcomeJ R Coll Physicians Lond19912532182221920209

- OwensDDennisMReadSDavisNOutcome of deliberate self-poisoning. An examination of risk factors for repetitionBr J Psychiatry199416567978017881782

- OwensDWoodCGreenwoodDCHughesTDennisMMortality and suicide after non-fatal self-poisoning: 16-year outcome studyBr J Psychiatry200518747047516260824

- PettitJWJoinerTEJrRuddMDKindling and behavioral sensitization: are they relevant to recurrent suicide attempts?J Affect Disord2004832–324925215555722

- PlattSBille-BraheUKerkhofAParasuicide in Europe: the WHO/EURO multicentre study on parasuicide. I. Introduction and preliminary analysis for 1989Acta Psychiatr Scand1992852971041543046

- ScoliersGPortzkyGvan HeeringenKAudenaertKSociodemographic and psychopathological risk factors for repetition of attempted suicide: a 5-year follow-up studyArch Suicide Res200913320121319590995

- SheikholeslamiHKaniCZiaeeAAttempted suicide among Iranian populationSuicide Life Threat Behav200838445646618724794

- SidleyGLCalamRWellsAHughesTWhitakerKThe prediction of parasuicide repetition in a high-risk groupBr J Clin Psychol199938Pt 437538610590825

- SinclairJMCraneCHawtonKWilliamsJMThe role of autobiographical memory specificity in deliberate self-harm: correlates and consequencesJ Affect Disord20071021–3111817258815

- StenagerENStenagerEJensenKAttempted suicide, depression and physical diseases: a 1-year follow-up studyPsychother Psychosom1994611–265738121978

- SuokasJSuominenKIsometsäEOstamoALönnqvistJLong-term risk factors for suicide mortality after attempted suicide – findings of a 14-year follow-up studyActa Psychiatr Scand2001104211712111473505

- SuominenKHIsometsäETHenrikssonMMOstamoAILönnqvistJKSuicide attempts and personality disorderActa Psychiatr Scand2000102211812510937784

- SuominenKIsometsäEOstamoALönnqvistJLevel of suicidal intent predicts overall mortality and suicide after attempted suicide: a 12-year follow-up studyBMC Psychiatry200441115099401

- TaylorCJKentGGHuwsRWA comparison of the backgrounds of first time and repeated overdose patientsJ Accid Emerg Med19941142382427894810

- TejedorMCDíazACastillónJJPericayJMAttempted suicide: repetition and survival – findings of a follow-up studyActa Psychiatr Scand1999100320521110493087

- TidemalmDLångströmNLichtensteinPRunesonBRisk of suicide after suicide attempt according to coexisting psychiatric disorder: Swedish cohort study with long term follow-upBMJ2008337a220519018040

- TownsendEHawtonKHarrissLBaleEBondASubstances used in deliberate self-poisoning 1985–1997: trends and associations with age, gender, repetition and suicide intentSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol200136522823411515700

- TrémeauFStanerLDuvalFSuicide attempts and family history of suicide in three psychiatric populationsSuicide Life Threat Behav200535670271316552986

- VerkesRJFekkesDZwindermanAHPlatelet serotonin and [3H]paroxetine binding correlate with recurrence of suicidal behaviorPsychopharmacology (Berl)1997132189949272764

- WangAGMortensenGCore features of repeated suicidal behaviour: a long-term follow-up after suicide attempts in a low-suicide-incidence populationSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol200641210310716362167

- WestlingSAhrénBTräskman-BendzLWestrinALow CSF leptin in female suicide attempters with major depressionJ Affect Disord2004811414815183598

- YstgaardMHestetunILoebMMehlumLIs there a specific relationship between childhood sexual and physical abuse and repeated suicidal behavior?Child Abuse Negl200428886387515350770

- ZahlDLHawtonKRepetition of deliberate self-harm and subsequent suicide risk: long-term follow-up study of 11,583 patientsBr J Psychiatry2004185707515231558

- DiekstraRFSuicide and suicide attempts in the European Economic Community: an analysis of trends, with special emphasis upon trends among the youngSuicide Life Threat Behav198515127423992615

- ReulbachUBleichSSuicide risk after a suicide attemptBMJ2008337a251219018042

- KapurNHouseAMayCCreedFService provision and outcome for deliberate self-poisoning in adults – results from a six centre descriptive studySoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol200338739039512861446