Abstract

Background

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most common psychiatric disorders worldwide. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment option for patients with SAD. In the present study, we examined the efficacy of group CBT for patients with generalized SAD in Japan at 1-year follow-up and investigated predictors with regard to outcomes.

Methods

This study was conducted as a single-arm, naturalistic, follow-up study in a routine Japanese clinical setting. A total of 113 outpatients with generalized SAD participated in group CBT from July 2003 to August 2010 and were assessed at follow-ups for up to 1 year. Primary outcome was the total score on the Social Phobia Scale/Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SPS/SIAS) at 1 year. Possible baseline predictors were investigated using mixed-model analyses.

Results

Among the 113 patients, 70 completed the assessment at the 1-year follow-up. The SPS/SIAS scores showed significant improvement throughout the follow-ups for up to 1 year. The effect sizes of SPS/SIAS at the 1-year follow-up were 0.68 (95% confidence interval 0.41–0.95)/0.76 (0.49–1.03) in the intention-to-treat group and 0.77 (0.42–1.10)/0.84 (0.49–1.18) in completers. Older age at baseline, late onset, and lower severity of SAD were significantly associated with good outcomes as a result of mixed-model analyses.

Conclusions

CBT for patients with generalized SAD in Japan is effective for up to 1 year after treatment. The effect sizes were as large as those in previous studies conducted in Western countries. Older age at baseline, late onset, and lower severity of SAD were predictors for a good outcome from group CBT.

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), often referred to as social phobia, is characterized by fear and avoidance of social situations. Epidemiological surveys have shown that SAD is the fourth most common psychiatric disorder,Citation1 with a lifetime prevalence of 12%.Citation2 SAD begins during adolescence and often persists.Citation3 Patients with SAD often suffer from comorbid depressionCitation4,Citation5 and other anxiety disorders.Citation6 According to such characteristics of the disorder, SAD causes significant social dysfunction, and patients with SAD frequently develop functional impairment at work and in their private lives, which decreases their quality of life.Citation7,Citation8 Therefore, providing appropriate treatment for SAD is important.

Previous studies have provided evidence that pharmacotherapy,Citation9 including benzodiazepines, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors, are effective during SAD treatment as well as during cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).Citation10 A number of randomized controlled trialsCitation11,Citation12 and strong evidence for a positive effect of CBT on SAD have been published. The effect size of CBT has been estimated at 0.71 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.56–0.85) by a recent meta-analysis,Citation13 and it showed lower relapse rates than treatments based on pharmacotherapy.Citation14

Some researchers have demonstrated the effectiveness of CBT in a group format. Because patients with SAD are often anxious and avoid small-group work, they can be exposed to fearful situations by attending sessions.Citation10 Furthermore, group CBT has greater cost-effectiveness compared with individual CBT.Citation15

From 2003 onward, we conducted group CBT for outpatients with SAD at the Department of Psychiatry, Nagoya City University Hospital, based on previous studies. Our preliminary posttreatment data (from July 2003 to January 2007, n = 57) show that group CBT is acceptable.Citation16 We have also published the long-term (1-year) effects on quality of lifeCitation17 (n = 57) and symptomatologyCitation18 (n = 62) in patients with SAD. These studies examined the baseline predictors of the outcomes, but none were found. These studiesCitation16–Citation18 also had limitations because of small sample size, and many dropout cases made it difficult to identify predictors. Furthermore, we included both the generalized and nongeneralized subtypes of SAD in these studies. Although both subtypes can be improved by CBT, the generalized subtype has more severe social anxiety symptoms and social function disability than those of the nongeneralized subtype, and patients are more impaired prior to and after treatment.Citation19 Our previous studies may have contaminated efficacy by including both subtypes.

To overcome these limitations, in the present study we accumulated twice the number of participants (n = 113) as in our previous studies,Citation16–Citation18 and we focused on the generalized subtype to present more conclusive data. Moreover, we adopted a mixed-model analysis, which is considered the most effective way to identify treatment outcome predictors. Many studies have attempted to identify predictors of treatment outcomes, but only a few specific predictors have been found.Citation20 Baseline predictors may enable us to provide CBT more effectively and to prevent dropout from treatment.

Furthermore, although CBT was originally developed in Western countries, some previous studies have discussed the cultural boundaries of SAD symptoms or SAD treatment.Citation21,Citation22 A condition called “taijin kyofusho” syndrome occurs in Japan and some other East Asian countries, as stated in the appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). From this perspective, exploring the efficacy of CBT for SAD has a significant meaning in Japan.

Thus, we conducted this study with the aim of identifying the long-term efficacy and predictors of group CBT for patients with generalized SAD in Japan.

Methods

Subjects

From July 2003 to August 2010, 113 outpatients with SAD were enrolled in the group-based CBT program at the Department of Psychiatry, Nagoya City University Hospital, Japan. All patients fulfilled the criteria for generalized SAD as the primary disorder according to the structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV. Furthermore, all patients met the following criteria: (1) no history of psychosis or bipolar disorder, or current substance-abuse disorder, (2) no previous CBT treatments, with agreement not to be involved in any other structured psychosocial therapies during treatment, and (3) absence of cluster B personality disorder. We included patients with current axis I disorders if symptoms were controlled sufficiently to allow joining a group session. For example, we included major depressive disorder or other current anxiety disorders or patients with axis II personality disorders except criterion (3).

All patients gave written informed consent after a full explanation of the study. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences.

Treatments

This study was conducted as a single-arm, naturalistic, follow-up study in a routine Japanese clinical setting. We followed the CBT manual for SAD written by Andrews et al,Citation23 and we modified and improved the program according to Clark and Wells’ model.Citation24 Treatment was conducted in groups of three patients led by one principal therapist and one cotherapist, and were scheduled for 120 minutes once per week.

The average number of sessions was 14 (range 12–20), depending on the needs of each group. The program included (1) psychoeducation about SAD (session 1), (2) introduction about the individual cognitive behavioral model of SAD (session 2), (3) experiments to drop safety behavior and self-focused attention (from session 8 to last session), (4) attention training to shift focus away from themselves to the task or the external social situation (sessions 4 and 5), (5) video feedback of role-playing in anxious situations to modify their self-image (sessions 6 and 7), (6) in vivo exposure using behavioral experiments to test the patient’s catastrophic predictions (from session 8 to last session), and (7) cognitive restructuring (session 3, from session 8 to last session). We assigned homework to the patients after every session. Among 113 patients, 98 patients (86.7%) completed CBT, and almost all of the patients (n = 109) finished all the exercise kinds, even when they were absent from a few sessions.

Eight therapists (five psychiatrists and three doctoral-level clinical psychologists), with more than 3 years of clinical practice with anxiety disorders, conducted the treatment program. Adherence to the treatment manual was monitored by group discussion once per month. We allowed patients to use antidepressants and benzodiazepines during CBT, because our study was based in a clinical setting and there is some evidence for combined pharmacologic/CBT therapy.Citation11,Citation25 Patients did not participate in any other structured psychotherapy while attending group CBT.

Assessment

The principal therapist conducted the mood- and anxiety-disorder sections of the structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV at baseline, for the SAD diagnosis, and any mood and anxiety comorbidities.

Patients’ demographic data were gathered at baseline, including such sociodemographic factors as sex, age, educational status, marital status, and employment status. Information about age of onset and duration of SAD, SAD subtype, psychiatric comorbidities, and medication use was also obtained.

The patients were assessed with self-report questionnaires at baseline, post-treatment, and by mail at the 1-year follow-up. Our primary outcome was the total Social Phobia Scale/Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SPS/SIAS)Citation26 score at the 1-year follow-up.

SPS/SIAS

The SPS and SIAS are 20-item self-report questionnaires with ratings on a 4-point scale from 0 (not at all characteristic or true of me) to 4 (extremely characteristic or true of me), and total scores of 0–80. A high score indicates severe symptoms. The SPS measures the fear of being observed, whereas the SIAS provides a measure of fear of social interaction. Sufficient internal consistency, reliability, and discrimination, as well as predictive and concurrent validity have been demonstrated for both original and Japanese versions.Citation27 Cronbach’s alphas of our sample for SPS/SIAS were 0.88/0.60–0.88.

Fear Questionnaire social phobia subscale

The Fear Questionnaire social phobia subscale (FQ-sp)Citation28 is a 5-item self-reported instrument for measuring the fear-motivated avoidance of being observed, performing, being criticized, and talking to authorities. Items are rated on a 9-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (would not avoid it) to 8 (always avoid it). A high score indicates severe symptoms. Good test–retest reliability and factor validity have been demonstrated.Citation29

Statistical analyses

We compared treatment completers with patients who dropped out using unpaired t-tests for continuous variables or chi-square tests for categorical variables. We also calculated Cohen’s d for the continuous variables. Treatment completers were defined as participants who had attended at least 80% of all treatment sessions and completed posttreatment and 1-year follow-up questionnaires.

The pretreatment and 1-year follow-up scores on SPS/SIAS were compared using paired t-tests to quantify outcomes from the CBT program. Furthermore, to examine the outcomes of the CBT program across various aspects of the disorder, pre- and posttreatment scores were compared for SPS, SIAS, and FQ-sp using paired t-tests, and pretreatment and 1-year follow-up were compared for FQ-sp using paired t-tests. To show the magnitude of the treatment effect, we calculated the effect size (M pretest – M posttest)/pooled standard deviation [SD]. All statistical analyses for these treatment outcomes were conducted twice: once based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle and once among the completers only. The ITT analyses were conducted using the last-observation-carried forward (LOCF) model, for which we used the mid-treatment data (after the eighth session) or the 3-month follow-up data, whichever were the last observational data available. We used the LOCF model to present more conservative treatment-effectiveness estimates.

We conducted mixed-model analyses to detect the baseline predictors of treatment outcome with the 1-year follow-up SPS/SIAS score as a dependent variable and the baseline demographic and clinical variables (sex, age, marital status, educational status, employment status, onset, duration of SAD, current mood disorder, current anxiety disorder, antidepressant use at baseline, benzodiazepine use at baseline, number of treatment sessions, severity) as variables. We converted continuous variables into categorical variables for this analysis. Age and onset of SAD age were categorized by Medline search criteria (age was divided into three categories: 13–18 years, 19–45 years, and ≥46 years; onset of SAD was divided into three categories: ≤12 years of age, 13–18 years of age, and 19–45 years of age). The number of treatment sessions was divided into two categories according to our definition of minimal session number (n = 12). We divided the variable of duration of SAD into two categories of ≤1 year or >1 year, because we wanted to explore the effectiveness of early treatment intervention. Baseline severity of SAD was defined by the baseline SPS total score, based on Heimberg et al,Citation30 with more than 34 being defined as severe.

All the statistical tests were two-tailed, and an alpha value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the data were examined using SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows.

Results

Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of patients and comparison of treatment completers and dropouts

One hundred and thirteen outpatients with SAD (57 males and 56 females; age range 14–63 years; mean ± SD 31.8 ± 10.4 years) were enrolled in our study. summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients and compares treatment completers with dropouts. All participants met the principal diagnostic criteria for the DSM-IV SAD generalized subtype.

Table 1 Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the patients and a comparison of treatment completers and dropouts

As a result of chi-square tests for categorical variables, onset of SAD and SPS total score at baseline showed P < 0.05, but no other major differences were observed between completers and dropouts. The number of sessions taken by patients on average was 14 (range 12–20).

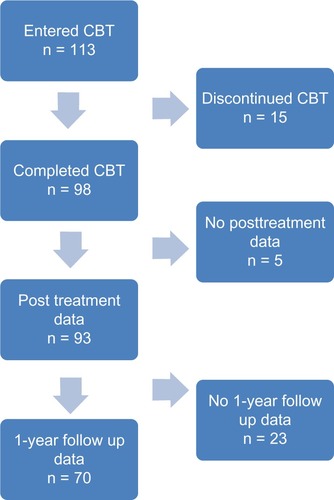

shows the number of patients at different time points. Of the 113 patients who were enrolled, 98 completed treatment and 70 finished the 1-year follow-up. Although pre- and posttreatment SPS were not normally distributed, we conducted analyses as we planned, because the other measures were normally distributed.

Changes in symptoms and function through treatment

shows the mean symptom scores and SDs of all measures for all participants (ITT population using the LOCF model) and pre- and posttreatment completers and pre- and 1-year follow-ups. An examination of the change in symptom measures (SPS, SIAS, and FQ-sp) between pre- and posttreatment and between pre- and 1-year follow-ups revealed significant improvements not only for the completers but also for the ITT samples (all P < 0.05).

Table 2 ITT and completers mean symptom scores and SDs at the pre- and post-treatment

Table 3 ITT and completers mean symptom scores and SDs at the pre-treatment and 1-year follow ups

Next, the effect sizes for each symptom measure were calculated, and the results are presented in and . The effect sizes for the total SPS/SIAS scores at the 1-year follow-up, which was our primary outcome, were 0.68 (95% CI 0.41–0.95)/0.76 (95% CI, 0.49–1.03) in the ITT sample and 0.77 (0.42–1.10)/0.84 (0.49–1.18) in completers. Based on the ITT sample analyses, effect sizes for assessment at posttreatment were SPS 0.64 (0.37–0.90), SIAS 0.76 (0.49–1.03), and FQ-sp 0.66 (0.39–0.93), and at 1-year follow-up FQ-sp was 0.76 (0.48–1.02).

Table 4 Effect sizes for ITT and completers at the pre- and post-treatment compared with our previous study

Table 5 Effect sizes for ITT and completers at the pre-treatment and 1-year follow ups

Effect sizes for treatment completers at posttreatment were SPS 0.81 (95% CI, 0.46–1.15), SIAS 0.76 (0.49–1.10), and FQ-sp 0.81 (0.47–1.15), and the effect size of the FQ-sp at 1-year follow up was 0.96 (0.61–1.31), indicating a greater change than that in the ITT sample.

All effect sizes were larger at 1-year follow-up than those at posttreatment.

Predictors of treatment outcomes at 1-year follow-up

summarizes the mixed-model analyses outcome. A significant difference was found for SIAS in the older age-group at baseline (P = 0.019), a lower severity on SPS (P = 0.000), and late onset of SAD for both SPS (P = 0.001) and SIAS (P = 0.000) as predictors of good treatment outcome.

Table 6 The mixed model analyses outcome for detecting the baseline predictors of the SPS and SIAS scores at the 1-year follow ups

Discussion

Main findings

The results indicate the long-term efficacy of a CBT program for Japanese patients with SAD generalized subtype. Although we focused on patients with the generalized subtype, who have more severe symptoms than those with the nongeneralized subtype, the effect sizes were as large as those in a meta-analysis conducted in Western countriesCitation13 and our previous study at posttreatment.

According to the effect-size calculation, our treatment program had significant effects at posttreatment that were maintained until the 1-year follow-up. This outcome is the same as that of a previous study, which demonstrated the maintenance efficacy of CBTCitation14 and indicates the possibility that patients are able to use treatment elements by themselves after group treatment.

Few CBT therapists are available for SAD treatment in Japan, and national health insurance does not include CBT for anxiety disorders. Thus, accumulating evidence for a positive effect of CBT in Japan is a matter of urgency, and we hope our study contributes to this purpose. Group CBT is more cost-effective than individual CBT in this regard, and we would like to diffuse this effective treatment for SAD in Japan.

We investigated baseline predictors for treatment outcomes. A number of studies have examined the role of particular variables in predicting the response to treatment; however, results have been inconsistent and inconclusive.Citation20 The severity of comorbid depression,Citation31,Citation32 symptomatic severity,Citation31 avoidant personality disorder,Citation33 and expectancyCitation32 have been suggested as possible follow-up predictors for group CBT.

Although some demographic variables (female, married, higher education) were possible follow-up predictors in a studyCitation34 that conducted individual CBT, and the aforementioned demographic variables were not statistically significant in our group CBT study, we believe that suitable characteristics of patients are different between group CBT and individual therapy.

We found that older age, late onset of SAD, and less severe symptoms on SPS were possible baseline treatment predictors for a good outcome. These results agreed with our clinical impression. We may have to pay more attention to patients who are contrary to those features by reflecting on those results.

Future studies should focus not only on pretreatment variables but also on the treatment process, such as homework compliance and the client–therapist relationship, as suggested by Scholing and Emmelkamp.Citation31 These factors may help improve the clinical practice of CBT for SAD.

Limitations

The present study had several limitations. First, this study was conducted in a routine Japanese clinical setting as a single-arm, naturalistic, follow-up study. Thus, a random control trial is needed to estimate the conservative efficacy of treatment.

Second, antidepressant and benzodiazepine medications were allowed during treatment, but information about the amount of drug consumption during the course was not collected. We are unable to consider dose effects of medications on CBT; however, use of medication at baseline was not a significant predictor of treatment outcomes in the present study.

Third, some may argue that there were no patients with avoidant personality disorder in our study. We used the structured clinical interview of the DSM-IV mood/anxiety module, but we did not use other modules considering patient load. We only excluded patients who were clinically diagnosed with personality B disorders in accordance with group therapy. The diagnosis of avoidance personality disorder is difficult, as is distinguishing between severe generalized SAD and avoidant personality disorder, thus we did not diagnose avoidant personality disorder rigidly in the aforementioned way.

Fourth, there were some statistical issues in our study. Multiple t-tests may have increased the risk for type I errors. However, the magnitude of the treatment effectiveness was quantified by effect size as well as the percentage reduction. Besides, data for pre- and posttreatment SPS were not normally distributed, although those for the other measures were normally distributed. This might have had some effect on the statistical validity of our study. However, we conducted post hoc Mann–Whitney analysis between completers and dropouts, and the result was not different.

Some may point out that we did not use the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale as the primary outcome, which is a widely used measure. Because this study was conducted as routine Japanese clinical work, follow-up assessments done by post- and self-reporting versions of thisCitation35 have not been validated in Japan to date.

Moreover, a recent studyCitation36 showed the effectiveness of attention training, which costs less than typical CBT. Although our program included attention training, we might be able to improve our program by emphasizing this component, according to the new findings.

Despite these limitations, this study provided evidence of long-term efficacy of group CBT for Japanese patients with generalized SAD. Although there is still room for improvement, our results favor the use of CBT for generalized SAD in Japan.

Conclusions

Group CBT resulted in improvements in Japanese patients with generalized SAD, and these improvements were maintained for up to 1 year after group CBT. We showed that older age at baseline, late onset, and lower severity of SAD were predictors of good outcome at 1-year follow-up for group CBT.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Department of Psychiatry and Cognitive-Behavioral Medicine, Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, and also by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 10103220) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests with regard to the present study.

References

- LiebowitzMRHeimbergRGFrescoDMTraversJSteinMBSocial phobia or social anxiety disorder: what’s in a name?Arch Gen Psychiatry200057219119210665624

- KesslerRCBerglundPDemlerOJinRMerikangasKRWaltersEELifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationArch Gen Psychiatry200562659360215939837

- KellerMBThe lifelong course of social anxiety disorder: a clinical perspectiveActa Psychiatr Scand Suppl2003417859412950439

- BeesdoKBittnerAPineDSIncidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the frst three decades of lifeArch Gen Psychiatry200764890391217679635

- KesslerRCStangPWittchenHUSteinMWaltersEELifetime co-morbidities between social phobia and mood disorders in the US National Comorbidity SurveyPsychol Med199929355556710405077

- ChartierMJWalkerJRSteinMBConsidering comorbidity in social phobiaSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol2003381272873414689178

- KesslerRCThe impairments caused by social phobia in the general population: implications for interventionActa Psychiatr Scand Suppl2003417192712950433

- DavidsonJRHughesDLGeorgeLKBlazerDGThe epidemiology of social phobia: findings from the Duke Epidemiological Catchment Area StudyPsychol Med19932337097188234577

- BlancoCSchneierFRSchmidtAPharmacological treatment of social anxiety disorder: a meta-analysisDepress Anxiety2003181294012900950

- HeimbergRGCognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder: current status and future directionsBiol Psychiatry200251110110811801235

- DavidsonJRFoaEBHuppertJDFluoxetine, comprehensive cognitive behavioral therapy, and placebo in generalized social phobiaArch Gen Psychiatry200461101005101315466674

- HofmannSGCognitive mediation of treatment change in social phobiaJ Consult Clin Psychol200472339339915279523

- AcarturkCCuijpersPvan StratenAde GraafRPsychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: a meta-analysisPsychol Med200939224125418507874

- LiebowitzMRHeimbergRGSchneierFRCognitive-behavioral group therapy versus phenelzine in social phobia: long-term outcomeDepress Anxiety1999103899810604081

- GouldRABuckminsterSPollackMHOttoMWMassachusettsLYCognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatment for social phobia: a meta-analysisClin Psychol (New York)199744291306

- ChenJNakanoYIetzuguTGroup cognitive behavior therapy for Japanese patients with social anxiety disorder: preliminary outcomes and their predictorsBMC Psychiatry200776918067685

- WatanabeNFurukawaTAChenJChange in quality of life and their predictors in the long-term follow-up after group cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder: a prospective cohort studyBMC Psychiatry2010108120942980

- FurukawaTANakanoYFunayamaTCBT modifies the naturalistic course of social anxiety disorder: Findings from an ABA design study in the routine clinical practicesPsychiatry Clin Neurosci2013In press.

- BrownEJHeimbergRGJusterHRSocial phobia subtype and avoidant personality disorder: effect on severity of social phobia, impairment, and outcome of cognitive-behavioral treatmentBehav Ther1995263467486

- EskildsenAHougaardERosenbergNKPre-treatment patient variables as predictors of drop-out and treatment outcome in cognitive behavioural therapy for social phobia: a systematic reviewNord J Psychiatry20106429410520055730

- HeimbergRGMakrisGSJusterHROstLGRapeeRMSocial phobia: a preliminary cross-national comparisonDepress Anxiety1997531301339323453

- WeissmanMMBlandRCCaninoGJThe cross-national epidemiology of social phobia: a preliminary reportInt Clin Psychopharmacol199611Suppl 39148923104

- AndrewsGCreamerMCrinoRHuntCLampeLPageAThe Treatment of Anxiety Disorders: Clinician Guides and Patient ManualsCambridgeCambridge University Press2002

- ClarkDWellsAA cognitive model of social phobiaHeimbergRGLiebowitzMHopeDASchneierFRSocial Phobia: Diagnosis, Assessment, and TreatmentNew YorkGuilford Press19956993

- BlomhoffSHaugTTHellströmKRandomised controlled general practice trial of sertraline, exposure therapy and combined treatment in generalised social phobiaBr J Psychiatry2001179233011435264

- MattickRPClarkeJCDevelopment and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxietyBehav Res Ther19983644554709670605

- KanaiYSasakawaSChenJSuzukiSShimadaHSakanoYDevelopment and validation of the Japanese version of Social Phobia Scale and Social Interaction Anxiety ScaleJpn J Psychosom Med20044411841850

- MarksIMBehavioural Psychotherapy: Maudsley Pocket Book of Clinical ManagementBristolJohn Wright1986

- MarksIMMathewsAMBrief standard self-rating for phobic patientsBehav Res Ther1979173263267526242

- HeimbergRGMuellerGPHoltCSHopeDALiebowitzMRAssessment of anxiety in social interaction and being observed by others: the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia ScaleBehav Ther19922315373

- ScholingAEmmelkampPMPrediction of treatment outcome in social phobia: a cross-validationBehav Res Ther199937765967010402691

- ChamblessDLTranGQGlassCRPredictors of response to cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobiaJ Anxiety Disord19971132212409220298

- FeskeUPerryKChamblessDRennebergBGoldsteinAAvoidant personality disorder as a predictor for severity and treatment outcome among generalized social phobicsJ Pers Disord199610174184

- LincolnTMRiefaWHahlwegbKWho comes, who stays, who profits? Predicting refusal, dropout, success, and relapse in a short intervention for social phobiaPsychother Res200515321022522011151

- FrescoDMColesMEHeimbergRGThe Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: a comparison of the psychometric properties of self-report and clinician-administered formatsPsychol Med20013161025103511513370

- HeerenAReeseHEMcNallyRJPhilippotPAttention training toward and away from threat in social phobia: effects on subjective, behavioral, and physiological measures of anxietyBehav Res Ther2012501303922055280