Abstract

Capgras syndrome consists of the delusional belief that a person or persons have been replaced by doubles or impostors. It can occur in the context of both psychiatric and organic illness, and seems to be related to lesions of the bifrontal and right limbic and temporal regions. Indeed, magnetic resonance imaging has revealed brain lesions in patients suffering from Capgras syndrome. This case study reports the findings of a thorough diagnostic evaluation in a woman suffering from Capgras syndrome and presenting with the following clinical peculiarities: obsessive modality of presentation of the delusional ideation, intrusiveness of such ideation (that even disturbed her sleep), as well as a sense of alienation and utter disgust towards the double. These characteristics bring to mind the typical aspects of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuroanatomic investigation, through magnetic resonance imaging, performed on this patient showed alteration of the bilateral semioval centers, which are brain regions associated with the emotion of disgust and often show alterations in subjects suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder. Hence, neuroimaging allows researchers to put forward the hypothesis of a common neuroanatomic basis for Capgras syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder, at least for cases in which the delusional ideation is associated with deep feelings of disgust and presents with a certain pervasiveness.

Introduction

Delusional misidentification syndromes are characterized by an interesting psychopathologic phenomenon in which patients misidentify familiar persons, objects, or themselves, believing that they have been replaced or transformed.Citation1,Citation2 The correct classification of these diseases is still unclear; within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV),Citation3 they could be included among the broader category of delusional disorders but, as reported in the literature, there is not always a concordance between the symptoms presented by the patients and the rigid diagnostic categories.Citation4 Delusional misidentification syndromes can occur in the case of idiopathic psychiatric illness as well as in the case of diffuse or focal brain damage, and are characterized by a pattern of neuropsychologic impairments (particularly affecting memory and perception) which are not indicators of the selectivity of these delusional phenomena. In fact, other variables, such as premorbid psychopathology and motivation, may be important in determining which patients are more vulnerable to developing delusional misidentification syndromes.Citation5

Among the delusional misidentification syndromes, Capgras syndrome is the most common and consists of the delusional belief that a person or persons have been replaced by doubles or impostors.Citation6 In 1923, this syndrome was described by Capgras and Reboul-Lachaux, and was originally termed “illusion des sosies”.Citation7 The Capgras delusion can be considered a symptom occurring in adults and in childrenCitation8 in the context of both psychiatric and organic illness.Citation9,Citation10 As a matter of fact, it can be associated with other psychiatric conditions, especially schizophrenia.Citation11 It can present as a complication of neurodegenerative disorders (such as multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease)Citation12,Citation13 and infective conditions,Citation10 or can even be a manifestation of drug toxicity.Citation14 Moreover, it seems to be related to lesions of bifrontal and right limbic and temporal regions.Citation9 Indeed, magnetic resonance imaging has revealed brain lesions in patients suffering from Capgras syndrome affecting in particular the frontal and subcortical regions.Citation15,Citation16 This delusion could also be due to a disconnection between the frontal lobes and right temporolimbic regions. Hence, it is impossible to link information regarding identification of the person and the emotions arising from such identification.Citation6 Psychodynamic explanations for the occurrence of such a particular delusion have been provided by some authors,Citation17,Citation18 even though these explanations have been regarded as insufficient.Citation19 From a psychodynamic point of view, the Capgras delusion arises from an altered affective response and leads to intolerable ambivalent feelings which are neutralized by “creation” of doubles.Citation17,Citation18 This case study reports the findings of thorough diagnostic evaluation in a woman suffering from Capgras syndrome.

Case report

A 53-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our Psychiatry Unit for hospitalization by her general practitioner. Anamnestic data collection revealed that the patient had had a difficult adolescence, due to the fact that her father had had a mistress and suffered from pathologic gambling. Notwithstanding, she had not experienced any previous psychopathologic problems in the past. She was a housewife with two daughters, and the eldest daughter had always been in conflict with her mother. On the day of her admission to hospital, the patient had a fatuous expression, seemed apathetic, and was suffering from considerable psychomotor retardation. She was distrustful of other patients because they were “too intrusive”. However, when approaching other patients, she showed a childish attitude and was disrespectful of conventional interpersonal distances. The patient had the delusional belief that her eldest daughter, whom she thought had disappeared for 12 months, had been replaced by an impostor. In fact, the previous year the patient’s daughter had left her house without telling her mother. The patient tried to get in touch with her, and the girl answered the phone saying that she was at work. Because her workplace was quite far off from her house, the patient thought that it was not possible for her daughter to arrive at work in such a short time. Hence, she believed that the person she had spoken to over the phone was an impostor who was replacing the daughter whom she thought had disappeared.

Her delusional belief was characterized by incorrigibility and unwarranted subjective conviction. The patient had two “proofs” to justify her belief: the distance of the workplace and the impostor’s makeup, which was heavier than that worn by her daughter.

The patient was experiencing not only the tragedy of a mother who had lost her daughter, but also the frustration of continuous deception by the “double”/impostor. Indeed, the patient thought that the “double” was imitating her daughter’s way of speaking so as to convince her (the patient) that she (the “double”) was her daughter. The patient had no idea where her daughter could be. However, she did nothing to find out where she was. In addition, even though she considered the impostor to be a menacing presence, the patient had a passive attitude towards the impostor, and treated her with indifference. Her mood was deflected owing to her daughter’s disappearance. Obviously, the patient had no insight into her illness. The Capgras delusion was the only unusual belief presented by this patient, who did not show any other psychotic symptoms. The clinical picture of this patient was peculiar: she was tormented by the thought of the “double” who, in addition, provoked a feeling of disgust. This feeling was caused by the fact that the “double” treated the patient in a confidential way in order to deceive her without feeling any real affection. This thought, which was particularly intrusive, caused her considerable distress and even disturbed her sleep; almost every night, she had difficulty in falling asleep at the thought of the painful condition of deception that she had to endure. In addition, this delusional belief was presented to the medical interviewers in an obsessive way, with perseveration regarding the subject (she constantly repeated that the woman was not her daughter), and the thought content restricted to it. The story about her daughter was the answer to simple questions that had nothing to do with the topic. The intrusive thoughts pertaining to her daughter’s disappearance and to the impostor were always present and did not fluctuate much over time.

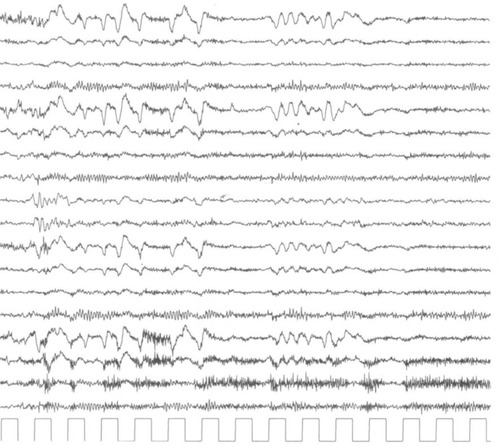

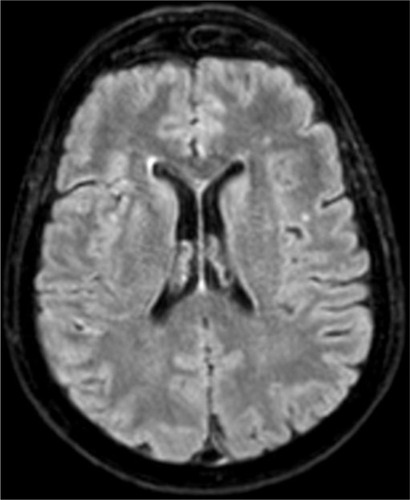

General physical examination was within normal limits. She did not drink alcohol or coffee, and did not use any illicit or recreational drugs. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)Citation20 was 27/30, indicating normal cognition. Items of the MMSE that the patient was less able to complete pertained to calculation and to short-term and long-term memory. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality DisordersCitation21 indicated an unspecified personality disorder, with a preponderance of paranoid and obsessive-compulsive personality traits. The electroencephalogram was characterized by background alpha activity and rapid rhythms in the frontocentral regions, bilaterally, as shown in . Magnetic resonance imaging (images obtained through fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, spin echo, and turbo field echo techniques, diffusion weighted in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes) showed moderate lesions in the frontal subcortical white matter and in the semioval centers on both sides. In particular, in long repetition time sequences, these cerebral areas showed hyperintensities compatible with a picture of gliosis, as shown in .

Discussion

The identification of an object implies an unconscious mental representation made available to the conscious part of the mind. The perception of an object is automatically connected to an emotion, produced in an unconscious way. In the abovementioned case, the cognitive unconsciousness of the patient processed the information, reaching erroneous conclusions regarding her daughter’s identity.Citation22 The cognitive models of face processing involve two stages: recognition of the face and generation of an affective response to the familiar face.Citation23 Ellis and YoungCitation24 have suggested considering Capgras syndrome as the “mirror image” of prosopagnosia; in patients with Capgras syndrome, there is an inability to associate an emotional content with the recognized visual image, while in those with prosopagnosia, emotional identification is intact and the visual one is damaged.Citation24,Citation25

From a psychodynamic point of view, one could put forward the hypothesis that the negative emotions linked to the conflicting relationship with her daughter were neutralized by the patient through the creation of a “double” who could be hated openly, and toward whom she could show feelings of disgust. The clinical picture of the patient presented some peculiarities, such as the considerable psychomotor retardation, fatuous expression, and childish way of relating to others. These characteristics led us to suspect a dementia status, also considering the well known association between Capgras syndrome and dementia,Citation26 but our suspicion was not confirmed on the MMSE. In addition, some aspects of the patient’s disorder reminded us of the typical characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorder, ie, the obsessive modality of presentation of delusional ideation, the intrusiveness of this ideation (that even disturbed her sleep), as well as a sense of alienation and utter disgust toward the impostor. However, in this case, the patient’s thoughts were egosyntonic, being related to her delusional belief that the daughter had disappeared, so the patient did not try to suppress them. It has been shown that the emotion of disgust itself is a fundamental aspect of obsessive-compulsive disorder.Citation27 Moreover, in a case of obsessive-compulsive disorder, a nondelusional variant of Capgras syndrome characterized by doubts regarding the substitution by doubles has been reported in literature.Citation28 Another study of cases of delusional misidentification syndromes in subjects suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder suggested that these syndromes could be the result of an association between obsessive fears and pre-existing cognitive deficits.Citation29 We know from the literature that Capgras syndrome is associated with organic illness in up to 40% of cases.Citation5 In our patient, both electroencephalography and magnetic resonance imaging showed alterations of an organic nature. Although several studies have correlated frontal and subcortical brain lesions with Capgras syndrome,Citation15,Citation16 to date there has been limited investigation of the correlation between specific cerebral areas and this peculiar delusional syndrome. The neuroanatomic investigation, through magnetic resonance imaging, performed on this patient showed hyperintensities in the frontal subcortical white matter and in the semioval centers on both sides, compatible with a picture of gliosis, thus indicating an alteration affecting these areas. The specific alteration of the bilateral semioval centers in Capgras syndrome is an interesting finding which, to the best of our knowledge, is new in the literature. These data encourage some speculation. The semioval centers are brain regions associated with the emotion of disgust and are often altered in subjects suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder,Citation30 which is notoriously highly sensitive to disgust.Citation31 Hence, this may be the first time that neuroimaging has allowed researchers to put forward the hypothesis of a common neuroanatomic basis for Capgras syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder, which could provide an explanation for the overlap of clinical characteristics between these two disorders (at least for cases in which the delusional ideation is associated with deep feelings of disgust and shows a certain pervasiveness). Some authors have even wondered if delusional misidentification syndromes are nothing but an unusual presentation of psychiatric disorders already considered in the DSM-IV.Citation3,Citation4 Indeed, there is still a lot to investigate with regard to the Capgras delusion, a phenomenon that is both fascinating and complex. Hence, research should be extended in order to provide a response to the many open questions on this subject.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChristodoulouGNDelusional Misidentification SyndromesBasel, SwitzerlandKarger1986

- JocicZDelusional misidentification syndromesJefferson Journal of Psychiatry1992104

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2002

- AttaKForlenzaNGujskiMHashmiSIsaacGDelusional misidentification syndromes: separate disorders or unusual presentations of existing DSM-IV categories?Psychiatry (Edgmont)20063566120975828

- FeinbergTERoaneDMDelusional misidentificationPsychiatr Clin North Am20052866568316122573

- Madoz-GúrpideAHillers-RodríguezRCapgras delusion: a review of aetiological theoriesRev Neurol201050420430 Spanish20387212

- CapgrasJReboul-LachauxJL’illusion des sosies dans un délire systématisé chronique. [The illusion of doubles in chronic systematized delusions]Bull Soc Clin Med Ment192311616 French

- MazzoneLArmandoMDe CrescenzoFDemariaFValeriGVicariSClinical picture and treatment implication in a child with Capgras syndrome: a case reportJ Med Case Rep2012640623186382

- HillersRodríguez RMadoz-GúrpideATirapuUstárroz JCapgras syndrome: a proposal of neuropsychological battery for assessmentRev Esp Geriatr Gerontol201146275280 Spanish21944325

- SalviatiMBersaniFSMacrìFCapgras-like syndrome in a patient with an acute urinary tract infectionNeuropsychiatr Dis Treat2013913914223355784

- SilvaJALeongGBThe Capgras syndrome in paranoid schizophreniaPsychopathology1992251471531448540

- SharmaAGarubaMEgbertMCapgras syndrome in a patient with multiple sclerosis: a case reportPrim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry20091127419956472

- FischerCKeelerAFornazzariLRingerLHansenTSchweizerTAA rare variant of Capgras syndrome in Alzheimer’s diseaseCan J Neurol Sci20093650951119650368

- CanagasabeyBKatonaCLCapgras syndrome in association with lithium toxicityBr J Psychiatry19911598798811790464

- Paillère-MartinotMLDao-CastellanaMHMasureMCPillonBMartinotJLDelusional misidentification: a clinical, neuropsychological and brain imaging case studyPsychopathology1994272002107846238

- LewisSWBrain imaging in a case of Capgras’ syndromeBr J Psychiatry19871501171213651660

- FishbainDASchiffmanJThe daughter as the principal “double” in a Capgras’ syndrome: psychodynamic correlatesAm J Psychother1986406076113812829

- O’ReillyRMalhotraLCapgras syndrome – an unusual case and discussion of psychodynamic factorsBr J Psychiatry19871512632653690120

- SinkmanAMThe Capgras delusion: a critique of its psychodynamic theoriesAm J Psychother1983374284386625025

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res1975121891981202204

- FirstMBGibbonMSpitzerRLWilliamsJBWBenjaminLSStructured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, (SCID-II)Washington DCAmerican Psychiatric Press Inc1997

- KihlstromJFThe cognitive unconsciousScience1987237144514523629249

- BreenNCaineDColtheartMModels of face recognition and delusional misidentification: a critical reviewCogn Neuropsychol200017557120945171

- EllisHDYoungAWAccounting for delusional misidentificationsBr J Psychiatry19901572392482224375

- EllisHDYoungAWQuayleAHDe PauwKWReduced autonomic responses to faces in Capgras delusionProc Biol Sci1997264108510929263474

- TsaiSJHwangJPYangCHLiuKMLoYCapgras’ syndrome in a patient with vascular dementia: a case reportKaohsiung J Med Sci1997136396429385782

- BerleDPhillipsESDisgust and obsessive-compulsive disorder: an updatePsychiatry20066922823817040174

- SteinRMLipperSAn obsessional variant of Capgras symptom: a case reportBull Menninger Clin19885252573337924

- MelcaIARodriguesCLSerra-PinheiroMADelusional misidentification syndromes in obsessive-compulsive disorderPsychiatr Q20138417518122922811

- NakamaeTNarumotoJShibataKAlteration of fractional anisotropy and apparent diffusion coefficient in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging studyProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry2008321221122618442878

- LawrenceNSAnSKMataix-ColsDRuthsFSpeckensAPhillipsMLNeural responses to facial expressions of disgust but not fear are modulated by washing symptoms in OCDBiol Psychiatry2007611072108017097073