Abstract

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures have long been known by many names. A short list includes hysteroepilepsy, hysterical seizures, pseudoseizures, nonepileptic events, nonepileptic spells, nonepileptic seizures, and psychogenic nonepileptic attacks. These events are typically misdiagnosed for years and are frequently treated as electrographic seizures and epilepsy. These patients experience all the side effects of antiepileptic drugs and none of the benefits. Video electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring is the gold standard diagnostic test that can make a clear distinction between psychogenic nonepileptic seizures and epilepsy. Video EEG allows us to correctly characterize the patient’s events and therefore properly diagnose and direct management. As a result, years of faulty management and wasted health care dollars can be avoided.

Introduction

Unlike epileptic seizures, psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) do not result from abnormal electrical discharges from the brain, but rather are a physical manifestation of a psychological disturbance. They fall under the broader category of somatoform disorders and are classified as conversion disorder based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. These events are involuntary and out of the patient’s conscious control. Rarely, PNES can occur secondary to malingering or factitious disorder, in which case the behavior is purposeful with intent for primary or secondary gain. Making this diagnosis is fraught with medicolegal hazards and is hard to prove.Citation1 PNES should also be differentiated from physiological, nonepileptic events such as syncope, cataplexy, migraine, paroxysmal movement disorders, breath-holding spells, and shuddering attacks in children.Citation1 The semiology of the event can help distinguish PNES from epilepsy. summarizes pertinent semiology and timing features that can assist in differentiating between PNES and epileptic seizures.Citation2 The importance of recognizing these semiological characteristics will be discussed in further detail later in this paper.

Table 1 Differences in semiology and timing between PNES and epileptic seizures

PNES is commonly misdiagnosed as epilepsy, and patients are often treated for years with an incorrect diagnosis.Citation3 It is a common indication for referral to epilepsy centers, where approximately 30% of epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU) admissions for refractory epilepsy are appropriately diagnosed with PNES.Citation3 In fact, it is the most frequent nonepileptic condition seen at epilepsy centers, more common than physiological nonepileptic conditions.Citation3 In addition, of the 1% of the US population with epilepsy, 5%–20% also experience PNES.Citation4

Over time, the tangible and intangible costs add up for the patient, the medical system, and society. The individual with PNES has an estimated US $100,000 lifetime cost for diagnostic tests, procedures, and medications.Citation3 In the US alone, up to US $900 million per year is unnecessarily spent on diagnostic evaluations, repeated labs, antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), and emergency department utilization for the evaluation and management of patients with PNES.Citation5

PNES occur more frequently in women than men (accounting for 80% of all cases) and the majority of patients are 15–35 years of age (83%).Citation3 However, some recent studies suggest that this condition might be more prevalent than was previously thought in men and in the elderly.Citation6 Based on one study, approximately 30% of patients undergoing video electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring in both the civilian and Veterans Administration populations (mostly male and of older age) were diagnosed with PNES.Citation6 PNES has also been observed in diverse ethnic groups.Citation7

With an average delay to diagnosis of 7–10 years, it is clear that the index of suspicion for PNES is not high enough when evaluating patients with refractory seizures.Citation8 Additionally, many physicians are unaware that a patient can have both epilepsy and PNES. Of note, one study reported that 10% of patients diagnosed with PNES also had epileptic seizures.Citation9 Therefore, when patients with multiple event types undergo EEG monitoring, additional care must be taken to confirm that all of the patients’ typical events have been captured and appropriately categorized. Otherwise, neither PNES nor epilepsy can be absolutely excluded.

The health risk of persons with PNES misdiagnosed with epilepsy is considerable. Aggressive treatment to stop the seizure sometimes results in oversedation, requiring paralysis and intubation. In one study in a pediatric population,Citation10 5%–20% of patients with presumed status epilepticus were eventually determined to be in “pseudo-status” and, therefore, could have avoided the dangers of paralysis and intubation if properly diagnosed. Other risks are posed by toxic medication levels, the insertion of central catheter lines, venous cutdowns, vagal nerve stimulator placement, and evaluations for temporal lobectomy.Citation5 Vocational costs add to the burden. The 50% disability rate for persons with PNES equals that of patients with epilepsy.Citation4 All these factors underscore the need for an accurate diagnosis early in the course, opening the door to appropriate treatments. Furthermore, delay to diagnosis worsens the prognosis for PNES.Citation11

Even though PNES are very common, there are limited data regarding outcomes. A few studiesCitation12,Citation13 have looked at event remission after the diagnosis of PNES is made with video EEG monitoring. At follow-up, approximately 30% of patients were shown to be event free. However, these studies are small and do not take into account whether the patients receive ongoing therapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).Citation12,Citation13

Video EEG monitoring background

Video EEG is the gold standard for the diagnosis of PNES. It simultaneously records the patient’s brain electrical activity and captures corresponding behaviors on video. This testing is indicated in all patients with frequent paroxysmal events that persist despite taking antiseizure medications. In most cases, the treating epileptologist can differentiate between PNES and epileptic seizures using video analysis alone. However, combined electroclinical analysis of the clinical semiology or clinical pattern of the event and the ictal EEG findings allows for a definitive diagnosis in nearly all cases.Citation14

No laboratory tests or imaging studies are as reliable as video EEG monitoring at identifying and characterizing PNES, and differentiating them from epileptic seizures. However, elevated serum prolactin may differentiate generalized tonic-clonic seizures from PNES.Citation15 Serum prolactin rise within 30 minutes of ictus onset may be helpful in differentiating generalized tonic-clonic seizures from PNES, but at best is useful as an adjunctive diagnostic test to the delineation of PNES from epileptic seizures, particularly since the absence of any change in prolactin level cannot exclude the possibility of an epileptic seizure.Citation2 Structural neuroimaging abnormalities can neither confirm nor exclude either disorder since PNES may occur in the presence of focal lesions such as mesial temporal sclerosis.Citation16

A glaring deficiency of routine and/or ambulatory EEG compared to the gold standard of continuous video EEG monitoring is the absence of video to correlate with the EEG findings. Background EEG findings can be misleading when trying to distinguish epileptic seizures from PNES, particularly when a typical event is not captured. For example, 30% of patients with epilepsy have normal EEGs at presentation.Citation17 On the other hand, there are nonspecific EEG abnormalities or benign variants (subtly different than normal waveforms, but not pathological) that can be seen in more than 10% of healthy individuals.Citation17 Frequently, these normal variants are read as pathological and can contribute to erroneous diagnosis in patients with PNES. In addition, one large retrospective study showed that approximately 0.5% of healthy individuals with neither a diagnosis of epilepsy nor PNES had “unequivocal” epileptiform discharges without any previous documented pathology or history of seizures.Citation18

Clinical history

When admitting patients to the EMU, special care must be taken to procure an in-depth history. This could give the necessary information that leads to the suspicion of PNES versus epilepsy. A lack of efficacy of AEDs may be the first sign that the events could be psychogenic. Like other somatoform disorders, patients with PNES often demonstrate features of suggestibility, such as the reproduction of symptoms upon the physician’s examination. Risk factors for PNES may include a history of physical and sexual abuse, and a floridly positive review of systems.Citation19 About three-quarters of patients report prior emotional or physical trauma such as abuse, bereavement, serious illness, accidents, or assault.Citation19 Chronic pain or a history of fibromyalgia are often associated with psychogenic symptoms, and their presence can have a high predictive value for PNES of 70%–80%.Citation1,Citation19

Semiology

Analysis of the ictal semiology (ie, video) is of paramount importance. Certain characteristics of motor phenomena are strongly associated with PNES: gradual onset or termination; occurrence of events during “pseudosleep”; discontinuous (stop-and-go) movements; irregular or asynchronous (out-of-phase) activity; side-to-side head movement; pelvic thrusting; opisthotonic posturing; stuttering; weeping; preserved awareness during bilateral motor activity; and postictal whispering.Citation1

Additional evaluation focusing on ocular and facial movements can help further distinguish between PNES and epilepsy.Citation2,Citation13 Eye closure, especially of long duration, is highly associated with PNES. Patients with PNES may also show geotropic eye movements (turning or movement of the eyes in the direction of gravity). Ictal stuttering and postictal whispering are also suggestive of PNES.Citation2,Citation13 On the other hand, there are features that can be very suggestive of epileptic seizures and that are not typically seen in PNES, such as postictal nose rubbing and cough, which are common in temporal lobe epilepsy, and stertorous breathing in the postictal period following an epileptic generalized tonic-clonic seizure. Stereotypy strongly suggests epileptic seizures rather than PNES.Citation1

Pelvic thrusting can be seen in both epilepsy (especially frontal lobe seizures) and PNES. Out-of-phase, or asynchronous, movements tend to favor PNES, especially if the movements wax and wane over many minutes and do not occur during sleep. In contrast, frontal lobe seizures typically arise from sleep, involve vocalization, as well as quick and tonic posturing or bicycling movements of the legs, and are brief.Citation2 Whether associated physical injuries can differentiate between PNES and epileptic seizures is a matter of debate. Some sources conclude that physical injuries can occur as a result of either epileptic seizures or PNES.Citation13 However, in our experience, objective injuries such as tongue bite and bone fracture are seen more frequently with epilepsy and subjective injury is often over-reported and exaggerated in the PNES population.

In a study of 120 seizures from 35 patients (36 PNES and 84 epileptic seizures), only a few clinical signs were reliable in predicting a diagnosis of PNES versus epilepsy.Citation20 Useful clues to the diagnosis of PNES included preserved awareness during bilateral motor activity, as unresponsiveness is almost always present during bilateral motor activity in an epileptic seizure. PNES were also predicted by eye flutter, as well as by events affected by the presence of bystanders (intensified or alleviated). Epileptic seizures were predicted by abrupt onset, eye opening/widening, and postictal confusion or sleep. Importantly, compared to an expert review of these signs on video recording, eyewitness reports of these symptoms were not reliable.Citation20

The categorization of PNES has been a difficult task in the past, as the semiology is varied. A few have made attempts at categorizations based on retrospective cluster analysis.Citation21 One study divided PNES into six stereotypic categories (utilizing video EEG): 1) rhythmic motor PNES; 2) hypermotor PNES characterized by violent movements; 3) complex motor PNES; 4) dialeptic PNES characterized by unresponsiveness without motor manifestations; 5) nonepileptic auras characterized by subjective sensations without external manifestations; and 6) mixed PNES with combinations of the aforementioned categories.Citation21

Another studyCitation22 conducted multiple correspondence analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis based on a review of video EEG studies to construct a practical and useful semiological classification of PNES. This study separated the patterns into five clusters of signs: 1) dystonic attack with primitive gestural activity; 2) paucikinetic attack with preserved responsiveness; 3) pseudosyncope; 4) hyperkinetic prolonged attack with hyperventilation and auras; and 5) axial dystonic prolonged attack.Citation22 The categorization of PNES has potential implications for diagnosis and prognosis, with a number of studies indicating that the outcome of PNES may vary among different types.Citation13,Citation23

EEG findings

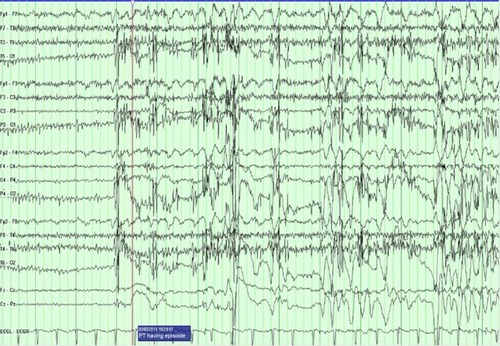

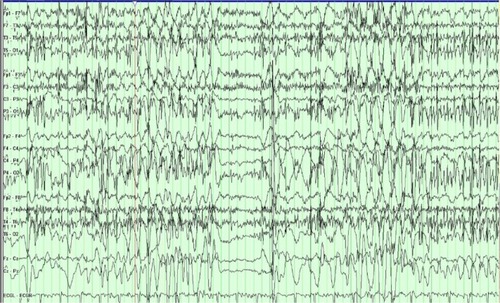

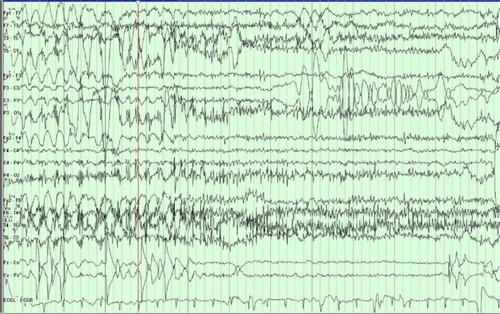

The diagnosis of PNES is made conclusively by coregistering video with EEG findings. While coregistered EEG findings can confirm a nonepileptic event origin, the differentiation between psychogenic versus physiologic etiology relies upon careful evaluations of the patient’s clinical history, event semiology, physical exam, psychosocial morbidities, and/or psychometric testing.Citation2 Typically in PNES, the EEG background is normal in the waking state prior to the ictus, during the ictus, and after the ictus (see –).

Figure 1 The PT transitions into a typical PNES.

Abbreviations: PT, patient; PNES, psychogenic nonepileptic seizure; EEG, electroencephalogram.

Figure 2 The patient is in the middle of a typical PNES.

Abbreviations: PNES, psychogenic nonepileptic seizure; EEG, electroencephalogram.

Figure 3 The patient transitions out of a typical PNES.

Abbreviations: PNES, psychogenic nonepileptic seizure; EEG, electroencephalogram.

Uninterpretable EEG recordings may occur if movement generates excessive artifact that obscures the EEG background. However, in these cases, completely normal EEG background immediately preceding and following a typical “convulsive event” is highly suggestive of PNES.Citation1 The ictal EEG can also be limited in some focal seizure types, as the EEG background may show minimal or no change. Focal seizures without clear alteration of awareness are the most common type of seizure that can be unaccompanied by significant EEG changes in approximately 30% of cases.Citation1 Seizures that occur without impairment of awareness involve sensory phenomena such as paresthesias, psychiatric symptoms of olfactory hallucinations, fear and déjà vu, focal motor or brief tonic movements, and autonomic symptoms. These are typically brief and can be of frontal or temporal lobe origin.Citation1

Seizure induction

What can be done in the cases when the typical event has not been captured during the designated monitoring period in the EMU? Provocative techniques including activation procedures and seizure “induction” can be very helpful. When combined with ictal video EEG monitoring, these techniques have a very high specificity for PNES.Citation24 However, provocative induction is only helpful when the reproduced event is confirmed by the patient or his/her family to be strongly characteristic of the habitual event of interest. Otherwise, due to the anxious and suggestible nature of some patients, provocative induction can frequently trigger nonspecific and nonrelevant symptoms.Citation24 Currently accepted techniques include photic stimulation, hyperventilation, and verbal suggestion. One advantage of photic stimulation and hyperventilation is that these maneuvers are used during routine EEG as well, and therefore do not appear out of the ordinary to the patient. Even without using placebo, provocative induction with photic stimulation, verbal suggestion, and hyperventilation can achieve up to an 84% success rate in capturing typical events.Citation25 An intravenous injection of saline is used in some centers, but is controversial because of ethical concerns.Citation25 The principle of suggestibility, a characteristic of all somatoform disorders, is the crucial component to all provocative techniques.

Delivering the diagnosis

After the diagnosis of PNES is definitively made, the question then arises as to how to approach the patient with this new and unfamiliar diagnosis. It is extremely helpful for discussions of expectations and the possibility of PNES to take place during the patient’s outpatient clinic visit, prior to admission for video EEG monitoring. Taking this step opens a dialogue of trust and transparency that will likely allow the patient to accept the diagnosis more readily when the final diagnosis is made.

The role of the epileptologist is of paramount importance in delivering the diagnosis of PNES. The initial explanation in the EMU after confirmation is probably the most important step in initiating treatment.Citation11 Patients and families are unlikely to comply with recommendations unless they understand and accept the diagnosis. A negative reaction to the explanation can affect outcomes. Therefore, the epileptologist must explain the diagnosis with unambiguous terms (for example, “stress-induced”) while simultaneously remaining compassionate, firm, and confident. The diagnosis of PNES must be clearly delineated from a diagnosis of epileptic seizures. Because this delivery of diagnosis is so important, many providers follow a templated script such as the protocol by Shen et al.Citation26 This protocol emphasizes the goal of conveying to the patient the importance of knowing the nonepileptic nature of the spells and the need for psychiatric follow-up. It also allows for elicitation of the patient’s sexual abuse history and the use of suggestion to aid in the control of PNES. When the PNES diagnosis is properly conveyed and then accepted by the patient, then up to ~30% of the patients enjoy remission of PNES, often without any further intervention.Citation27 This concept further underscores the importance of a proper delivery of the PNES diagnosis by the epileptologist.

The epileptologist can continue to be involved afterwards and can help with weaning AEDs, though the psychological treatment should be addressed by the psychologist or psychiatrist. AEDs do not cure and do not typically help PNES, and AED toxicity may worsen this disorder.Citation28 A study that monitored the discontinuation of AEDs in 78 patients with PNES revealed that the majority of these patients experienced a reduction in the frequency of PNES when taken off the medication, indicating that withdrawal of AED treatment is not only safe but can also improve outcomes.Citation29

The issues of driving and disability should be addressed after the diagnosis of PNES is made. Unfortunately, there is little data regarding PNES and driving safety; however, no evidence exists, which demonstrates that patients with PNES have an increased risk of car accidents. Physicians tend to take an experiential approach with this. Some may restrict driving in all PNES patients, while others approach this restriction on a case-by-case basis.Citation30 Since PNES is a psychiatric diagnosis that requires treatment by mental health professionals, disability should ideally be determined by the treating mental health professionals.

Securing follow-up with mental health professionals is of paramount importance in patients with video EEG-confirmed PNES. Unfortunately, these services are not always readily available. Additionally, there are obstacles to treatment, including mental health providers that are not familiar with PNES and its treatment. Providing a video recording of the patient’s typical event can be a useful method to educate and reinforce the diagnosis with the mental health team.Citation31

Treatment

There is mounting evidence that CBT is the treatment of choice for PNES. Goldstein et alCitation32 reported that CBT significantly reduced event activity in patients with PNES compared with standard medical care. Another prospective trial evaluated the effect of CBT on the reduction of PNES events.Citation33 Subjects with video EEG-confirmed PNES were treated with CBT in 12 weekly outpatient sessions. Seventeen of 21 patients completed the CBT intervention, and eleven of the 17 completers reported no seizures by the final CBT session. Mean scores on scales of depression, anxiety, somatic symptoms, quality of life, and psychosocial functioning showed improvement from baseline. This study demonstrates that CBT reduces PNES events and improves psychiatric symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life.Citation33

There is also growing evidence that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medications may play a role in modifying the depression that is often seen concurrently with PNES.Citation34,Citation35 Additionally, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may play a role in reducing the frequency of events in patients with PNES. However, this must be taken with a degree of skepticism, as larger scale studies are needed with higher levels evidence.Citation34,Citation35

Conclusion

PNES is a disorder that affects a significant percentage of patients with presumed epileptic seizures. On average, it takes 7–10 years to arrive at a definitive diagnosis of PNES, suggesting that the index of suspicion is too low and that misdiagnosis is commonplace.Citation4 This leads to years of inappropriate treatment, during which time patients may be consigned to take multiple AEDs and suffer a myriad of untoward side effects while deriving none of the purported benefits of these medications. A proper diagnosis is absolutely key to appropriate treatment. Video EEG is a unique tool that is the gold standard for the diagnosis of PNES. There is no better test for arriving at a near certain diagnosis. Once the diagnosis has been securely established, the appropriate delivery and explanation of the disorder must be given to the patient. The prognosis relies heavily on the clarity of this explanation and on whether the patient receives adequate follow-up from mental health providers. Although the current standard management of PNES includes CBT, there is still much to be learned regarding optimum treatment strategies and outcomes.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BenbadisSRNonepileptic behavioral disorders: diagnosis and treatmentContinuum (Minneap Minn)2013193 Epilepsy71572923739106

- LaFranceWCJrPsychogenic nonepileptic seizuresCurr Opin Neurol200821219520118317280

- BenbadisSRO’NeillETatumWOHeriaudLOutcome of prolonged video-EEG monitoring at a typical referral epilepsy centerEpilepsia20044591150115315329081

- LaFranceWCJrBenbadisSRAvoiding the costs of unrecognized psychological nonepileptic seizuresNeurology200666111620162116769930

- MartinRCGilliamFGKilgoreMFaughtEKuznieckyRImproved health care resource utilization following video-EEG-confirmed diagnosis of nonepileptic psychogenic seizuresSeizure1998753853909808114

- SalinskyMSpencerDBoudreauEFergusonFPsychogenic nonepileptic seizures in US veteransNeurology2011771094595021893668

- DevinskyOGazzolaDLaFranceWCDifferentiating between non-epileptic and epileptic seizuresNat Rev Neurol20117421022021386814

- ReuberMFernándezGBauerJHelmstaedterCElgerCEDiagnostic delay in psychogenic nonepileptic seizuresNeurology200258349349511839862

- BenbadisSRAgrawalVTatumWOHow many patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures also have epilepsy?Neurology200157591591711552032

- PakalnisAPaolicchiJGillesEPsychogenic status epilepticus in children: psychiatric and other risk factorsNeurology200054496997010690994

- CartonSThompsonPJDuncanJSNon-epileptic seizures: patients’ understanding and reaction to the diagnosis and impact on outcomeSeizure200312528729412810341

- ArainAMHamadaniAMIslamSAbou-KhalilBWPredictors of early seizure remission after diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizuresEpilepsy Behav200711340941217905668

- ReuberMPukropRBauerJHelmstaedterCTessendorfNElgerCEOutcome in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: 1 to 10-year follow-up in 164 patientsAnn Neurol200353330531112601698

- AvbersekASisodiyaSDoes the primary literature provide support for clinical signs used to distinguish psychogenic nonepileptic seizures from epileptic seizures?J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201081771972520581136

- ChenDKSoYTFisherRSTherapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyUse of serum prolactin in diagnosing epileptic seizures: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of NeurologyNeurology200565566867516157897

- LoweMRDe ToledoJCRabinsteinAAGiullaMFMRI evidence of mesial temporal sclerosis in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizuresNeurology200156682311274334

- MellersJDThe approach to patients with “non-epileptic seizures”Postgrad Med J20058195849850416085740

- GregoryRPOatesTMerryRTElectroencephalogram epileptiform abnormalities in candidates for aircrew trainingElectroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol199386175777678394

- BenbadisSRA spell in the epilepsy clinic and a history of “chronic pain” or “fibromyalgia” independently predict a diagnosis of psychogenic seizuresEpilepsy Behav20056226426515710315

- SyedTULaFranceWCJrKahrimanESCan semiology predict psychogenic nonepileptic seizures? A prospective studyAnn Neurol2011696997100421437930

- SeneviratneUReutensDD’SouzaWStereotypy of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: insights from video-EEG monitoringEpilepsia20105171159116820384722

- HubschCBaumannCHingrayCClinical classification of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures based on video-EEG analysis and automatic clusteringJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201182995596021561887

- SelwaLMGeyerJNikakhtarNBrownMBSchuhLADruryINonepileptic seizure outcome varies by type of spell and duration of illnessEpilepsia200041101330133411051130

- LancmanMEAsconapéJJCravenWJHowardGPenryJKPredictive value of induction of psychogenic seizures by suggestionAnn Neurol19943533593618122889

- BenbadisSRJohnsonKAnthonyKInduction of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures without placeboNeurology200055121904190511134393

- ShenWBowmanESMarkandONPresenting the diagnosis of pseudoseizureNeurology19904057567592330101

- McKenziePOtoMRussellAPelosiADuncanREarly outcomes and predictors in 260 patients with psychogenic nonepileptic attacksNeurology2010741646920038774

- NiedermeyerEBlumerDHolscherEWalkerBAClassical hysterical seizures facilitated by anticonvulsant toxicityPsychiatr Clin (Basel)19703271845424766

- OtoMEspieCPelosiASelkirkMDuncanRThe safety of antiepileptic drug withdrawal in patients with non-epileptic seizuresJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200576121682168515944179

- BenbadisSRBlusteinJNSunstadLShould patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures be allowed to drive?Epilepsia200041789589710897163

- BenbadisSRThe problem of psychogenic symptoms: is the psychiatric community in denial?Epilepsy Behav20056191415652726

- GoldsteinLHChalderTChigwedereCCognitive-behavioral therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a pilot RCTNeurology201074241986199420548043

- LaFranceWCMillerIWRyanCECognitive behavioral therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizuresEpilepsy Behav200914459159619233313

- LaFranceWCKeitnerGIPapandonatosGDPilot pharmacologic randomized controlled trial for psychogenic nonepileptic seizuresNeurology201075131166117320739647

- LaFranceWCSycSDepression and symptoms affect quality of life in psychogenic nonepileptic seizuresNeurology200973536637119652140