Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to determine which antipsychotic is most effective for the treatment of acute schizophrenia with catatonic stupor.

Patients and methods

Data were obtained from the medical records of 450 patients with the diagnosis of schizophrenia, who had received acute psychiatric inpatient treatment between January 2008 and December 2010 at our hospital. Among them, 39 patients (8.7%) met the definition of catatonic stupor during hospitalization. The diagnoses of schizophrenia in all 39 patients were reconfirmed during the maintenance phase. We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of these 39 patients to investigate which antipsychotics were chosen for treatment during the period from admission to recovery from catatonia, at the time of discharge, and 12 and 30 months after discharge.

Results

As compared to other antipsychotics, it was found out that use of quetiapine had better outcomes and hence was used more often. A total of 61.5% of patients were on quetiapine at the time of recovery from catatonia and 51.3% of patients were on quetiapine at the time of discharge as compared to only 17.9% of patients on quetiapine on admission. However, at 12 and 30 months after discharge, the rates had decreased to 38.4% and 25.6%. Similarly, of 29 patients who were not administered electroconvulsive therapy, quetiapine was used at significantly higher rates at the time of recovery from catatonia (48.3%) than at the time of admission (17.2%). All 39 patients had received an antipsychotic as the first-line treatment and some antipsychotics might have contributed to the development of catatonia.

Conclusion

This study suggests that quetiapine is a promising agent for the treatment of schizophrenia with catatonic stupor during the acute phase.

Introduction

Catatonia is a syndrome characterized by marked psychomotor abnormalities associated with schizophrenia, mood disorders, general medical conditions, drug withdrawal, and toxic drug states.Citation1 The clinical symptoms of catatonia are stupor, catalepsy, excessive and purposeless motor activity, extreme negativism, mutism, peculiarities of voluntary movement, echolalia, and echopraxia.Citation2,Citation3 Catatonia is observed in 5%–15% of psychiatric patients who require acute psychiatric hospital treatment. The predilection of psychiatrists to diagnose catatonic patients with schizophrenia appears to be based on historical reasons.Citation4 However, previous studies show that most cases of catatonia are caused by mood disorders, irrespective of the age group, while 10%–20% of them are caused by schizophrenia.Citation5–Citation7

Malignant catatonia is a condition in which psychomotor symptoms of catatonia are accompanied by autonomic instability or hyperthermia.Citation8 This frequently fatal condition cannot be distinguished from neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) either clinically or by laboratory tests, which leads to the conclusion that NMS is a variant form of malignant catatonia, and that treating catatonia with antipsychotics is recognized as a risk factor for the development of NMS.Citation9–Citation11

Benzodiazepines (BZP) and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) are the only recognized treatments of catatonia.Citation5,Citation12–Citation16 Numerous articles indicate that BZP are rapidly effective, safe, and easily administered and are therefore regarded as suitable for first-line treatment for catatonia. If catatonic symptoms do not resolve rapidly with BZP, ECT is indicated. It may be necessary in some cases to treat with antipsychotics, but some authors recommend that antipsychotics should be avoided altogether in patients with catatonia because their use may be harmful.Citation6,Citation17

The number of cases of catatonia due to schizophrenia is minor, but the treatment of acute schizophrenia with catatonia is very complex, and the use of antipsychotics in patients with catatonia is controversial.Citation6 Catatonic symptoms of patients with schizophrenia are somewhat less likely to respond to BZP.Citation12,Citation18 Even if catatonic symptoms are resolved rapidly with BZP, they may recur without adequate treatment of the underlying cause.Citation5 However, which antipsychotic is most effective for the treatment of acute schizophrenia with catatonia has not been determined. To our knowledge, there is no more suggestive indication for treating schizophrenia with catatonia than the case reports of successful treatment with aripiprazole,Citation19,Citation20 risperidone,Citation21,Citation22 olanzapine,Citation23,Citation24 ziprasidone,Citation25 and clozapine.Citation26 In particular, catatonic stupor states have considerable potential for serious complications, which include dehydration, venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and pneumonia. To determine the most effective antipsychotic for the treatment of acute schizophrenia with catatonic stupor, we reviewed the medical records of 39 patients with the diagnosis of schizophrenia with catatonic stupor.

Methods

The sample data was obtained from the medical records of 450 patients with the diagnosis of schizophrenia, not including schizoaffective disorder, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV),Citation2 who had received acute psychiatric inpatient treatment between January 2008 and December 2010 on the acute psychiatric ward of the Okayama Psychiatric Medical Center. Among them, with the exclusion of patients with catatonic stupor associated with general medical conditions, drug withdrawal, and toxic drug states, 39 patients (8.7%) met the definition of schizophrenia with catatonic stupor during hospitalization. All patients had formal medical evaluations by an internist to rule out underlying medical conditions that might have contributed to their psychiatric symptoms. The diagnoses of schizophrenia in all 39 patients were reconfirmed during the maintenance phase through clinical interview by each attending physician.

Because our hospital had no specific treatment algorithm, patients with schizophrenia characterized by catatonia were merely treated with antipsychotics in the same way as those without catatonia at the discretion of the attending physician.

Retrospectively, we reviewed the medical records of 39 patients with the diagnosis of schizophrenia with catatonic stupor to investigate which antipsychotics were used for treatment during the period from admission to recovery from catatonia, at the time of discharge, and 12 and 30 months after discharge. We defined “recovery from catatonia” as a mental state without catatonic symptoms or recurrence of catatonia during hospitalization. All 39 patients had made a “recovery from catatonia” prior to discharge. To assess the severity, we routinely used the Bush–Francis Catatonia Rating ScaleCitation3 and Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale in the acute and maintenance phases. We also investigated the presence of fever (>38°C), high serum creatine kinase (h-CK; >500 IU/L), NMS (on the basis of the criteria for NMS of Caroff and Mann),Citation27 duration of catatonia, other pharmacotherapies, and co-treatment with ECT. We classified the condition of patients with stupor in the presence of both fever and h-CK as “severe,” and defined the others as “less severe.”

The Institutional Review Board of our hospital approved this study. Because data for this study were collected in the course of routine clinical care, and these data were analyzed retrospectively and anonymized, informed consent was neither sought nor obtained.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics 19 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were analyzed using the independent sample t-test; categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. The level of significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

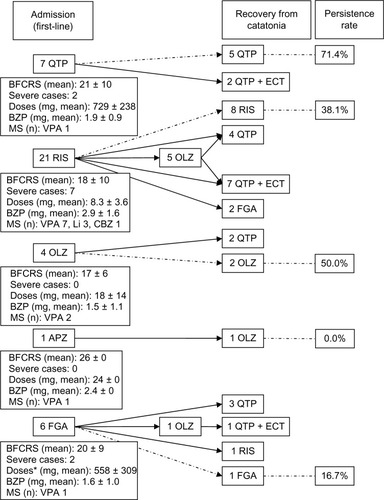

Of 39 patients with catatonic stupor, 28 and 11 patients met the criteria of less severe and severe stupor, respectively (). is a flow chart of antipsychotics used for the 39 patients during the period from admission to recovery from catatonia.

Figure 1 A flow chart of antipsychotics used for 39 patients during the period from admission to recovery from catatonia.

Abbreviations: APZ, aripiprazole; BFCRS, Bush–Francis Catatonia Rating Scale; BZP, benzodiazepine dosage (lorazepam equivalent); CBZ, carbamazepine; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; Li, lithium carbonate; MS, mood stabilizers; OLZ, olanzapine; QTP, quetiapine; RIS, risperidone; VPA, sodium valproate.

Table 1 Clinical data of 39 patients

Thirty-two patients (82.1%) had an established diagnosis of schizophrenia prior to presenting with catatonia. The mean duration of untreated psychosis of eleven patients with first-episode was 31.0 ± 46.2 weeks. The mean time interval between the initial diagnosis of schizophrenia and the time-point of presentation with catatonia of 28 patients with multi-episode was 13.8 ± 10.4 years.

The frequency of catatonic symptoms, in order of declining frequency, were as follows: immobility/stupor, mutism and staring, 39/39; posturing/catalepsy, 36/39; mannerism, 30/39; rigidity and withdrawal, 26/39; grimacing, 24/39; autonomic abnormality, 22/39; negativism, 20/39; excitement, 19/39; impulsivity, 14/39; gegenhalten, 10/39; verbigeration, 9/39; stereotypy, 7/39; waxy flexibility, 5/39; ambitendency, 4/39; automatic obedience and combativeness, 2/39; echopraxia/echolalia and perseveration, 1/39; mitgehen and grasp reflex, 0/39.

Our data shows that only quetiapine (QTP) was used at significantly higher rates at the time of recovery from catatonia (n=24, 61.5%, P<0.001) and discharge (n=20, 51.3%, P=0.002) than at the time of admission (n=7, 17.9%). Similarly, of 29 patients who were not administered ECT, QTP was used at significantly higher rates at the time of recovery from catatonia (n=14, 48.3%, P=0.012) than at the time of admission (n=5, 17.2%). However, at 12 and 30 months after discharge, the rates had decreased to 38.4% (n=15, P=0.044) and 25.6% (n=10, P=0.41).

The rate of QTP use was significantly higher in patients with severe stupor than in patients with less severe stupor at the time of recovery from catatonia (P=0.001) and discharge (P<0.001). The tendency was decreasing at 12 and 30 months after discharge (P=0.18 and P=0.088).

One and two patients developed NMS during treatment with first-generation antipsychotics and risperidone, respectively. Two of these three patients with NMS were treated by combination of medication and ECT, and another patient was treated with high-dose BZP. No patient treated with QTP as first-line treatment developed exacerbation of catatonia or severe extrapyramidal side effects.

The mean dosage (± standard deviation [range]) of QTP was 727 (±212 [300–1100]) mg/day at the time of recovery from catatonia (n=24). Treatment with dosages of QTP near the approved maximum (750 mg/day in Japan) was safe under conditions in which other antipsychotics are risky. From the time of recovery from catatonia to discharge, the mean dosages of QTP for patients who were administered ECT decreased (from 805 to 733 mg/day), and those for patients who were not administered ECT increased (from 671 to 727 mg/day). Only one patient was treated with high-dose BZP (7.2 mg, equivalent to lorazepam 6 mg or more daily), and 33 patients were treated with low-dose BZP. From the time of recovery from catatonia to 30 months after discharge, QTP was switched to other antipsychotics for 16/24 patients (insufficient efficacy, eight; sedation, three; hyperglycemia, two; weight gain, one; initiation of depot, two), and other antipsychotics were switched to QTP for 2/15 patients (dysphoria, one; extrapyramidal side effects, one).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a naturalistic investigation indicating that QTP might be a promising agent in the treatment of acute schizophrenia with catatonic stupor. Further, QTP might be more effective than other antipsychotics in the presence of catatonic stupor, fever, and h-CK. Only QTP was used at significantly higher rates at the time of recovery from catatonia and discharge than at the time of admission. The same was true in patients who were not administered ECT. The rate of QTP use at the time of recovery from catatonia and discharge was significantly higher in patients with severe stupor than in patients with less severe stupor. On the other hand, the rates had decreased at 12 and 30 months after discharge. Therefore, QTP was specifically more effective during the acute phase than the maintenance phase in the treatment of schizophrenia with catatonic stupor. However, five limitations apply.

First, the rate of QTP use is not necessarily equivalent to the effectiveness of QTP because our research was performed at a single hospital without a specific treatment algorithm and we investigated the medical records retrospectively. Thus, the possibility of physicians’ preferences in drug selection cannot be ruled out. The attending physician might have chosen QTP with the possibility in mind that the underlying causes of catatonia were mood disorders such as bipolar depression, for which QTP is effective and first-line treatment.Citation28 Most catatonic patients suffer from mood disorders.Citation5,Citation6 If a history of present illness is unclear, the underlying cause of catatonia cannot be confirmed because it is difficult to conduct a structured interview with patients with catatonic stupor. However, all of the physicians at Okayama Psychiatric Medical Center during the period of study did not have a marked predilection for QTP. We most frequently used risperidone as first-line treatment for patients with acute schizophrenia characterized by catatonic stupor in the same way as those without catatonia. Further, we generally chose QTP or olanzapine as second-line treatment if first-line antipsychotics were not efficacious or poorly tolerated. Eventually most patients recovered from catatonia and were discharged with QTP or a combination of QTP and ECT. Moreover, we would like to consider the prescription of antipsychotics of patients with the diagnosis of schizophrenia without catatonia (n=175), who received acute psychiatric hospital treatment between April 2008 and March 2009 at our psychiatric acute inpatient ward. Although the investigation period is different from that of this report, the rate of QTP use for non-catatonic schizophrenia patients was continuously about 10% (admission, 9.7%; discharge, 8.0%; 12 months after discharge, 13.2%) in our hospital.Citation29

Second, this study is a retrospective chart review and the sample size (n=39) is too small. Third, the effectiveness of BZP combined with mood stabilizers was not considered. Fourth, a more favorable outcome might have been obtained from high-dose BZP without antipsychotics during catatonia. Only one patient had been treated with high-dose BZP in our case series. High-dose BZP trial remained a first option in the treatment of catatonia whatever the condition associated with.Citation4,Citation30 Antipsychotic treatment might be one factor that resulted in the development of catatonia. Fifth, clozapine, which may have beneficial effects for catatonia in psychotic patients,Citation31 was not used during the acute phase in this study.

The mean dosages of QTP at discharge for patients with severe stupor was significantly lower than those for patients with less severe stupor, because patients with severe stupor were administered ECT at a significantly higher rate than patients with less severe stupor. From the time of recovery from catatonia to discharge, the dosages of QTP for patients who were administered ECT had decreased to improve the tolerability of medication, and the dosages of QTP for patients who were not administered ECT had increased to treat remaining psychotic symptoms.

Catatonia is thought to be predominantly caused by dopamine hypoactivity, specifically at D2 receptors, which leads to an increase in the release of glutamate in an attempt to increase dopamine activity.Citation32 In studies on rat models, QTP was shown to increase the release of dopamine, nor-epinephrine, and glutamate in the medial prefrontal cortex in a dose-dependent fashion without affecting the release of serotonin or gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in the same area.Citation33 BZP potentiates the action of gamma-aminobutyric acid, which can inhibit glutamate hyperactivity.Citation32 It is possible that there are combined effects of QTP and BZP in the treatment of catatonia.

To further support the hypoactive D2 receptor theory, several case reports exist that demonstrate high-potency typical antipsychotics either causing or worsening catatonia.Citation31,Citation32 The antagonism of D2 receptors by QTP is the weakest of all antipsychotics. The affinity for D2 receptors of QTP is weaker than that of intrinsic dopamine (loose binding),Citation34,Citation35 and it is the most rapid to dissociate from D2 receptors (transient blockade).Citation36,Citation37 Thus, QTP may be tolerable when patients are at risk of NMS if treated with antipsychotics. However, it is necessary to consider the benefits and risks of QTP because cases of NMS have been reported in conjunction with all antipsychotics including QTP.Citation38

Although the efficacy of QTP in the treatment of acute schizophrenia with catatonic stupor cannot be confirmed given the small number of cases, retrospective study design which merely describes physician preference and the concurrent use of ECT and/or BZP, our study indicated that this antipsychotic agent may be somewhat better tolerated in patients with catatonic stupor.

Acknowledgments

No financial support for this study was provided. We thank Drs Suguru Ishizu and Jun Goshima for their assistance in conceiving the idea and methodology of this study and writing the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FinkMTaylorMACatatonia. A Clinician’s Guide to Diagnosis and TreatmentCambridge, UKCambridge University Press2003

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1994

- BushGFinkMPetridesGDowlingFFrancisACatatonia. I. Rating scale and standardized examinationActa Psychiatr Scand19969321291368686483

- FinkMShorterETaylorMACatatonia is not schizophrenia: Kraepelin’s error and the need to recognize catatonia as an independent syndrome in medical nomenclatureSchizophr Bull201036231432019586994

- RosebushPIMazurekMFCatatonia and its treatmentSchizophr Bull201036223924219969591

- TaylorMAFinkMCatatonia in psychiatric classification: a home of its ownAm J Psychiatry200316071233124112832234

- GhaziuddinNDhosscheDMarcotteKRetrospective chart review of catatonia in child and adolescent psychiatric patientsActa Psychiatr Scand20121251333822040029

- SingermanBRahejaRMalignant catatonia – a continuing realityAnn Clin Psychiatry1994642592667647836

- WhiteDACatatonia and the neuroleptic malignant syndrome – a single entity?Br J Psychiatry19921615585601393347

- CarrollBTTaylorREThe nondichotomy between lethal catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndromeJ Clin Psychopharmacol19971732352389169979

- FinkMTaylorMAThe many varieties of catatoniaEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci2001251Suppl 1I8I1311776271

- RosebushPIMazurekMFCatatonia: re-awakening to a forgotten disorderMov Disord199914339539710348460

- UngvariGSLeungCMWongMKLauJBenzodiazepines in the treatment of catatonic syndromeActa Psychiatr Scand19948942852888023696

- YassaRIskandarHLalinecMCletoLLorazepam as an adjunct in the treatment of catatonic states: an open clinical trialJ Clin Psychopharmacol199010166682307736

- BushGFinkMPetridesGDowlingFFrancisACatatonia. II. Treatment with lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapyActa Psychiatr Scand19969321371438686484

- HawkinsJMArcherKJStrakowskiSMKeckPESomatic treatment of catatoniaInt J Psychiatry Med19952543453698822386

- FinkMRediscovering catatonia: the biography of a treatable syndromeActa Psychiatr Scand Suppl2013127s44114723215963

- UngvariGSChiuHFChowLYLauBSTangWKLorazepam for chronic catatonia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over studyPsychopharmacology (Berl)1999142439339810229064

- KirinoEProlonged catatonic stupor successfully treated with aripiprazole in an adolescent male with schizophrenia: a case reportClin Schizophr Relat Psychoses20104318518820880829

- StrawnJRDelgadoSVSuccessful treatment of catatonia with aripiprazole in an adolescent with psychosisJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol200717573373517979595

- GrenierERyanMKoEFajardoKJohnVRisperidone and lorazepam concomitant use in clonazepam refractory catatonia: a case reportJ Nerv Ment Dis20111991298798822134459

- ValevskiALoeblTKerenTBodingerLWeizmanAResponse of catatonia to risperidone: two case reportsClin Neuropharmacol200124422823111479394

- BabingtonPWSpiegelDRTreatment of catatonia with olanzapine and amantadinePsychosomatics200748653453618071103

- GuzmanCSMyungVHWangYPTreatment of periodic catatonia with atypical antipsychotic, olanzapinePsychiatry Clin Neurosci200862448218778449

- AngelopoulosEKCorcondilasMKolliasCTKioulosKTBergiannakiJDPapadimitriouGNA case of catatonia successfully treated with ziprasidone, in a patient with DSM-IV delusional disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol201030674574621057243

- HungYYYangPSHuangTLClozapine in schizophrenia patients with recurrent catatonia: report of two casesPsychiatry Clin Neurosci200660225625816594953

- CaroffSNMannSCNeuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant hyperthermiaAnaesth Intensive Care19932144774788214562

- VietaEValentíMPharmacological management of bipolar depression: acute treatment, maintenance, and prophylaxisCNS Drugs201327751552923749421

- TakakiMYoshimuraBKonoT[Treatment of schizophrenia at emergency unit in Okayama Psychiatric Medical Center, Japan: Effectiveness and selection of antipsychotics at acute and maintenance, intervention and prognosis]Jpn J Clin Psychopharmacol201013943955 Japanese

- LinCCHuangTLLorazepam-diazepam protocol for catatonia in schizophrenia: A 21-case analysisCompr Psychiatry2013

- EnglandMLOngürDKonopaskeGTKarmacharyaRCatatonia in psychotic patients: clinical features and treatment responseJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci201123222322621677256

- CarrollBTLeeJWYAppianiFThomasCThe Pharmacotherapy of CatatoniaPrimary Psychiatry20101744147

- YamamuraSOhoyamaKHamaguchiTEffects of quetiapine on monoamine, GABA, and glutamate release in rat prefrontal cortexPsychopharmacology (Berl)2009206224325819575183

- RichelsonESouderTBinding of antipsychotic drugs to human brain receptors focus on newer generation compoundsLife Sci2000681293911132243

- KasperSTauscherJKüfferleBBarnasCPezawasLQuinerSDopamine- and serotonin-receptors in schizophrenia: results of imaging-studies and implications for pharmacotherapy in schizophreniaEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci1999249Suppl 4838910654113

- TakanoASuharaTIkomaYEstimation of the time-course of dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in living human brain from plasma pharmacokinetics of antipsychoticsInt J Neuropsychopharmacol200471192614764214

- KapurSSeemanPDoes fast dissociation from the dopamine d(2) receptor explain the action of atypical antipsychotics?: A new hypothesisAm J Psychiatry2001158336036911229973

- El-GaalySSt JohnPDunsmoreSBoltonJMAtypical neuroleptic malignant syndrome with quetiapine: a case report and review of the literatureJ Clin Psychopharmacol200929549749919745653