Abstract

The relapse rate for many psychiatric disorders is staggeringly high, indicating that treatment methods combining psychotherapy with neuropharmacological interventions are not entirely effective. Therefore, in psychiatry, there is a current push to develop alternatives to psychotherapy and medication-based approaches. Cognitive deficits have gained considerable importance in the field as critical features of mental illness, and it is now believed that they might represent valid therapeutic targets. Indeed, an increase in cognitive skills has been shown to have a long-lasting, positive impact on the patients’ quality of life and their clinical symptoms. We hereby present four principal arguments supporting the use of event-related potentials (ERP) that are derived from electroencephalography, which allow the identification of specific neurocognitive deficiencies in patients. These arguments could assist psychiatrists in the development of individualized, targeted therapy, as well as a follow-up and rehabilitation plan specific to each patient’s deficit. Furthermore, they can be used as a tool to assess the possible benefits of combination therapy, consisting of medication, psychotherapy, and “ERP-oriented cognitive rehabilitation”. Using this strategy, specific cognitive interventions could be planned based on each patient’s needs, for an “individualized” or “personalized” therapy, which may have the potential to reduce relapse rates for many psychiatric disorders. The implementation of such a combined approach would require intense collaboration between psychiatry departments, clinical neurophysiology laboratories, and neuropsychological rehabilitation centers.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, “… there is no health without mental health… ”.Citation1 Mental disorders make up an important independent contribution to the burden of non-communicable diseases worldwide. In fact, neuropsychiatric conditions account for up to one quarter of all disability-adjusted life years (ie, the sum of years lived with disability and years of life lost).Citation1 A psychiatrist’s main responsibility is to render accurate diagnoses that guide the selection of appropriate medication for severely mentally ill patients.Citation2 A crucial problem in psychiatry, which affects both research and clinical work, is that in practice it is difficult to strictly apply the scientific method to the investigation of human mental illness, since the evaluations should (at least) include analyses of both the mind and the brain when assessing normal and aberrant behaviors.Citation3 A consequence of this complexity is that, even if psychopathological states can effectively be alleviated by a combination of psychotherapy and neuropharmacological interventions, the relapse rate for several psychiatric disorders is tremendously high.Citation4 For example, the relapse rate for manic episodes in bipolar disorders was found to be 50% at 1 year, and 70% at 5 years.Citation5 Similarly, the relapse rate following a first episode of schizophrenia was reported to be 35% at 18 months, and 74% at 5 years.Citation6 In other words, there is still much to learn in order to fill this existing gap between a “partial recovery”, which allows patients to return home, and the achievement of a “complete recovery”.Citation7

The complexity surrounding the treatment of mental illness is also illustrated by alcohol dependence, which constitutes one of the most severe and widespread public health problems. Indeed, it is estimated that 3%–8% of all deaths and 4% of all disability-adjusted life years worldwide are attributable to alcohol.Citation1 Without intervention, detoxification alone does little to prevent an alcoholic’s subsequent relapse. During clinical trials, placebo control groups showed a relapse rate of up to 85%, even if hospitalized until complete remission of the physical withdrawal symptoms.Citation8 Similarly, there is little evidence supporting that antidepressants alter in any way the risk factors that lead to relapse and recurrence. Consequently, most patients with chronic or recurrent depression are encouraged to stay on medication indefinitely.Citation9 In addition, while it has been well established that maintenance treatment with antipsychotic medication decreases relapse rates, a substantial proportion of patients suffering from schizophrenia either relapse despite taking medication or have trouble adhering to antipsychotic treatment.Citation10 All of the above fuels the current strong interest for the development of alternatives to psychotherapy and medication.Citation11 In recent years, we have seen the emergence of several intervention strategies aimed at improving psychiatric treatment, such as multisystemic,Citation12 cognitive behavioral,Citation13 or mindfulnessCitation14 therapies. The goal of these “new” interventions is evidently not to discredit existing treatment methods, but to provide a complementary set of tools to be used by clinicians to improve current patient assessment.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to present four key arguments that support the use of event-related potential (ERP)-based cognitive assessment in combination with psychotherapy and medication to develop more efficient psychiatric therapies. It is now largely accepted that psychiatric disorders are brain disorders,Citation15 and brain-related tools, such as electroencephalography (EEG)Citation16 or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS),Citation17 have already proven their value for the management of psychiatric diseases. For instance, the combined use of rTMS and EEG enables the noninvasive evaluation of functional connections between brain areas, and provides a tool to investigate cortical activity.Citation18 Thus, a non-invasive input (TMS) known spatial and temporal characteristics with directional and precise chronometric data can be applied to the study of the brain’s local reactivity and the interactions between different brain regions.Citation19 This emerging technique allows for instance to observe that, during an 8 to 10 minute long EEG session with single-pulse TMS over the right premotor cortex, patients suffering from schizophrenia present reduced evoked gamma oscillations in the frontal cortex, reinforcing the hypothesis of an intrinsic dysfunction of the frontal thalamo-cortical circuit.Citation20 In this paper, we focus on ERPs, since by allowing the evaluation of the entire information processing stream, they can help pinpoint the specific neurocognitive functions that should be rehabilitated in each patient through specific and individualized cognitive remediation procedures. The aim of this paper is not to provide an exhaustive review of the literature pertaining to ERPs and psychiatric disorders, but to systematically illustrate four reasons why we think that it is now time to incorporate cognitive ERPs as a requisite step in clinical evaluations and use them to direct the development of an individualized therapy for mentally ill patients. This approach should also include a cognitive neuropsychological rehabilitation step, as an integrative part of the “whole process” that is classically only based on psychotherapy and medication. We will discuss the advantages, limitations, and perspectives associated with the clinical use of ERPs and we will propose new ways in which this technique can be effectively incorporated into patient care.

Argument 1: the cognitive process is a key element of psychopathological states

Cognitive deficits have gained considerable importance in the field as critical features of mental illness, and it is now believed that they might represent valid therapeutic targets.Citation21 Indeed, several studies have provided consistent evidence that mental illness involves significant cognitive impairment. For instance, virtually all areas of cognition, such as perception, attention, and memory, are known to be impaired in the schizophrenic individual,Citation22 as well as in patients of other psychiatric afflictions, such as euthymic bipolar disorder,Citation23 alcohol-dependence,Citation24 or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).Citation25 In schizophrenic patients, literature data reports a substantial decrease in cognitive function of about 1.0–1.75 standard deviations below the normal mean.Citation26 Moreover, some variability in the cognitive domain was also reported in euthymic bipolar patients (large effect sizes [d≥0.8] for executive functions and small effect sizes [0.2≤db0.5] for sustained attention).Citation23 However, a proven connection between the onset of a mental illness and the presence of cognitive impairment would be needed in order to establish the requirement for cognitive therapeutics.Citation27 Additionally, while there is overwhelming evidence that medication can reduce the severity of clinical symptoms, cognitive gains are either poor or undetectable.Citation21 Thus, it is currently accepted that cognitive impairment and symptomatic manifestations of mental illness require separate therapeutic approaches.Citation28

Cognitive retraining procedures (CRPs) have brought new applications to psychiatric rehabilitation.Citation29 Cognitive remediation is a behavioral intervention designed to improve cognition in patients who have suffered a cognitive decline.Citation30 The major elements of psychiatric rehabilitation focus on highlighting the patient’s strengths, improving vocational/social competencies, working with environmental facts of an individual’s life, and instilling a sense of mastery and hope.Citation31 From this perspective, cognitive retraining techniques range from assistive or prosthetic devices (including computers, diaries, and/or lists) to approaches that focus on enhancing the patient’s efficiency, (eg, mnemonic strategies).Citation32 Many studies have demonstrated that the use of CRPs can enhance cognitive performance in diverse psychiatric diseases,Citation33 and that these improvements are stable up to at least 6 months after the treatment is discontinued.Citation34 Additionally, CRP-related cognitive gains have been proved to translate to improvements in real world activities,Citation35 with greater impact than any drug treatment.Citation21 For example, in a single case study involving a schizophrenic patient,Citation35 Levaux et al demonstrated that the usage of an attention training technique leads to the following beneficial effects: i) at the cognitive level, a specific improvement in selective attention, attention switching, and resistance to distractive interference; and ii) at the clinical level, a reduction in intrusive thoughts in daily life and a general decrease in symptoms stable up to at least 6 months. Overall, cognitive remediation is a therapy that engages patients in learning activities that enhance the neurocognitive skills relevant to their chosen recovery goals.Citation36 A number of approaches to remediating cognition in schizophrenia have been developed and studied over the last 20 years. At the time of writing this article, this literature has been reviewed in six meta-analytic studies. Five of these, while differing in focus, determined that it has moderate to large effect sizes;Citation37–Citation41 the remaining one didn’t.Citation42 Moreover, with the spread of CRP’s application to patients suffering from schizophrenia, positive outcomes with CRP for other psychiatric disorders, such as unipolar depression,Citation43 social phobia,Citation44 ADHD,Citation45 and alcohol dependenceCitation46 have begun to appear in the literature. Overall, these data are consistent with the general idea that recognizing the nature of the cognitive impairment involved in a specific mental illness will be very useful for the development of treatment and rehabilitation strategies.Citation29

Although the usefulness of CRPs for the treatment of psychiatric disorders is gradually becoming more accepted, several questions regarding how to use them in clinical practice still remain to be resolved. Among other concerns, it is unknown whether cognitive impairments will be detected in all patients or just on a case-by-case basis.Citation27 Also, the assignment of impairment requires the comparison of patients’ results to those of a “normal” or “standard” cognitive control; however, normal values may be difficult to define, mainly because of the healthy individuals’ variability in cognitive function. In fact, it appears that, for instance, around 20% of schizophrenics generally perform within the normal range, only showing subtle evidence of impairment in specific cognitive domains.Citation47 Indeed, the human mind can be defined by several cognitive domains, such as attention, memory, language, or executive functions, any of which may prove to be altered.Citation48 This requires rehabilitation specialists (usually neuropsychologists) to thoroughly assess the cognitive status of each domain in order to decide the appropriate rehabilitative treatment. This process may be complicated by two factors: i) the fractionation of each cognitive domain implies the involvement of various neural networks (eg, executive function refers to a wide range of cognitive processes [including problem-solving, flexibility, inhibition, planning, and decision-making], and a patient’s performance in one executive function may have little or no predictive value for how the patient will perform in another);Citation49 and ii) time pressure is an important feature of the clinical examination, because cognitive screening needs to identify genuine impairment in as little time as possible, using an easily administered instrument.Citation50

In the following arguments, we will describe how and why we believe that cognitive ERPs can aid in the cognitive screening process. A general screening of main cognitive functions can be achieved by performing rapid tasks, which are easily implementable in clinical practice and have the potential to index the cognitive areas that require further assessment and/or rehabilitation by neuropsychologists.

Argument 2: the ERP method, a highly adapted tool to investigate the sequence of cognitive processes

The main goal of cognitive psychology has been to define the different stages that are required to achieve a final performance for each human cognitive function.Citation51 Indeed, every cognitive function (eg, recognizing an emotion on a face, recalling an event, reading a text, or making a decision) is associated with various cognitive stages. In fact, advances in brain imaging techniques (namely positron emission tomography [PET] and functional resonance magnetic imaging [fMRI]) have revealed that each of the serial cognitive stages is implemented within separate neural processes in order to achieve normal function.Citation52

The fact that healthy cognitive functions are implemented within distributed neural networks has important implications for the understanding of mental disorders. Firstly, the use of advanced imaging methods enabled the study of the neurobiology of mental disorders, confirming the fact that mental disorders have a neurobiological component (ie, they are not only functional or psychogenic conditions).Citation53 Secondly, imaging technology contributed insight into the pathological mechanisms of mental disorders, demonstrating that a functional alteration may result from an isolated brain lesion (eg, after a stroke) or deficient interactions between different brain regions (functional connectivity).Citation54 In this regard, imaging analysis can also provide a better understanding of the mechanisms of action of psychopharmaceuticals, potentially aiding in the search for novel therapeutic targets.Citation53

The study of blood flow (fMRI) or glucose metabolism (PET) in certain areas of the brain during activation tasks enables the identification of the areas of the brain that are activated or deactivated during specific cognitive tasks. Therefore, by comparing patients to controls, we can observe which brain activities are deficient. However, from a purely cognitive perspective, these data have an important limitation, residing on the fact that brain images are averaged on seconds. Thus, it is impossible to relate specific brain activations to the different cognitive stages involved in the task.Citation55 In other words, the excellent anatomical resolution of brain imaging techniques (3–4 mm for fMRI) might allow the visualization of the brain network involved in a certain task, but its coarse temporal resolution (1–2 seconds) impedes the determination of the activation sequence. For this purpose, we should recur to electrophysiological tools, and more precisely, to cognitive ERPs.Citation56

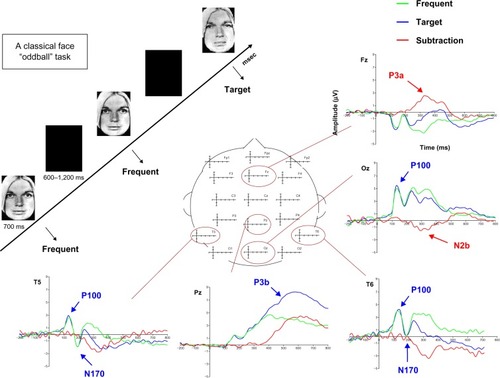

ERPs, which are derived from electroencephalography, are highly sensitive and have the potential to monitor brain lectrical activity with a fine temporal resolution (on the order of milliseconds). Thus, when healthy individuals perform a cognitive task, it is possible to observe the various electrophysiological components representing the cognitive stages utilized to achieve “normal” performance.Citation56 illustrates the different electrophysiological components representing the various cognitive stages needed to perform a simple task.

Figure 1 Illustration of the different ERP components recorded in a face-oddball task, in which participants have to detect as quickly as possible the appearance of a target “emotional sad” face among a train of frequent neutral faces by clicking on a button. The P100 component, recorded around 100 ms, refers to the visual perceptive analysis of the stimulus, and can be modulated through attention by different mechanisms such as complexity or motivation. The N170 component is a bilateral occipito-temporal negativity, recorded around 170 ms that refers to the structural encoding of facial information in order to generate a representation of the observed face in short-term memory. The N2b/P3a is a bipolar complex, obtained by subtracting the activity recorded for frequent stimuli from the one obtained for targets, with a posterior negativity recorded around 250 ms, referring to the allocation of attentional resources, while the frontal P3a is more sensitive to stimulus novelty. This complex is functionally seen as the switch of attention needed to process something new appearing in the environment. Finally, the P3b component is a parietal activity indexing pre-motor response stages that shows that the facial representation created in short-term memory for frequent faces has been updated, so that a behavioral motor response may be prepared.

Abbreviation: ERP, event-related potentials.

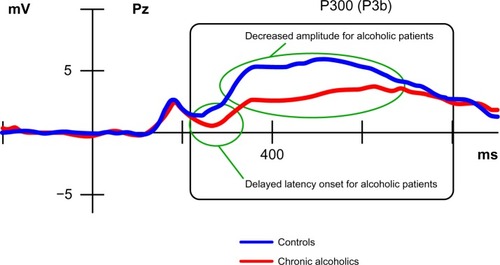

Another highly valuable aspect of cognitive ERPs is that they can permit the identification/detection of the electrophysiological component(s) consistent with the onset of a dysfunction, allowing the inference of impaired cognitive stages.Citation56 In other words, by using a well characterized task and analyzing which ERPs show decreased amplitude and/or delayed latency compared to normal values, it is possible to deduce which ERP component is responsible for the cognitive deficit.Citation56 illustrates the well-known P300 component, a late, long-lasting parietal positive wave, which is decreased and delayed in alcoholic patients compared to matched controls. However, while P300 deficit is common in many psychiatric afflictions, there is also an abundance of literature reporting; for instance, many earlier ERP components, such as the mismatch negativity or the sensory gating P50, but also later ones, such as the N400 indexing language semantic processes, are affected in alcoholic,Citation57 as well as in schizophrenicCitation58 patients. This suggests that during illness, various cognitive stages of the information-processing stream may be affected, and that the recorded ERP components may be considered as biological markers of the disease, indexing specific pathophysiological mechanisms that may or may not recover with the illness remission.Citation59

Figure 2 Illustration of a disturbed P300 (P3b) component resulting from the comparison of alcoholic patients with healthy matched controls.

Obviously, ERPs also suffer from some limitations. Their spatial resolution is very weak, so that inferences can only be made on the neural generators of the observed components, and parameters of ERPs (latency and amplitude) are subject to large inter-individual differences, so that the collection of normative data may prove fastidious.Citation56 Nevertheless, cognitive ERPs are advantageous, because they allow the assessment of the different stages used in the information-processing stream during performance of a task. Therefore, how and why could this technique be useful to psychiatrists in their daily clinical practice?

Argument 3: a similar behavioral deficit may originate from different cognitive levels

The most widely used and studied ERP component is the P300 component.Citation60 This component is of particular interest because it is functionally related to various complex cognitive processes, such as decision-making and cognitive closure phenomena, which are associated with different types of response-related cognitive activities.Citation61 Many studies investigating P300 in dementia, schizophrenia, depression, alcoholism, drug addiction, anxiety, or personality disorders have described disturbances in recorded latency and amplitude values of this component compared to healthy individuals. These differences have been associated with deficits in behavioral performance and can indicate the severity of a clinical state, as well as its possible evolution.Citation62

For example, if we consider the literature on the ability to recognize emotional facial expressions (EFE) in psychiatric populations, two main points emerge: i) at a behavioral level, many patients with psychiatric diseases display a deficit in emotional recognition, which can be indexed by decreased performance rates and longer response latencies compared to controls;Citation63 and ii) at an electrophysiological level, this behavioral deficit is associated with a decreased and delayed P300 component.Citation64 However, an important question in the field has revolved around the events occurring in the information-processing stream prior to the P300 component (ie, before the response-related stages). By using an emotional oddball task,Citation64,Citation65 we demonstrated that even if different psychopathological populations displayed a similar behavioral deficit in EFE recognition, this deficit originated at different cognitive levels, as indexed by cognitive ERPs. Indeed, while patients suffering from alcohol dependence or schizophrenia displayed altered ERP components affecting all information-processing streams (from perceptive-visual P100, to attention N2b and response-related P300 components),Citation66,Citation67 depressed people exhibited only a disturbed P300 component (with intact earlier components).Citation68 On the other hand, ecstasy users presented differences starting at the level of attention (N2b).Citation69 In other words, similar patterns at the behavioral level can result from different disturbances in cognitive processes from one population to another. This point has great clinical relevance, because it suggests that a similar pattern of deficit may be attributable to different neurocognitive disturbances, supporting the notion that similar behavioral deficits should be differently rehabilitated.

From a clinical point-of-view, it might not be a surprise that there are neurocognitive differences linked to different neuropsychiatric afflictions, especially considering the specificity of the pathophysiological mechanisms associated with distinct mental illnesses. However, interestingly, we also observe that such neurocognitive differences can be seen between individuals within a specific population that have a certain type of behavioral deficit. For instance, among anxious patients, Rossignol et al showed that those suffering from generalized anxiety disorder only displayed P300 differences when confronted with emotional oddball task,Citation70 whereas people with social anxiety showed earlier differences starting from the perceptive P100 component.Citation71 This suggests that social anxiety and trait anxiety should be considered separately and treated independently.Citation72 This realization is of great relevance, because it suggests that patients who display a similar group of symptoms and belong to a closed psychiatric category might have deficits that originate from different levels of the cognitive process.

Overall, the monitoring of ERPs is useful for identifying the cognitive origin of a behavioral deficit. By temporally analyzing the information-processing stream, the root causes of behavioral problems can be identified as perceptive, attention, or response related. Current data suggest that such differences not only exist between the various neuropsychiatric afflictions, but also among different patients categorized in the same psychiatric category. Therefore, the next important question is: how can such information be useful for psychiatrists?

Argument 4: once specific cognitive deficiencies are defined, directed cognitive retraining procedures may help to alleviate symptoms in homogeneous subgroups of patients

Thanks to an optimal temporal resolution, ERPs allow the assignment of a behavioral deficit to its cognitive origin. This feature of ERP analysis is of great clinical relevance, since it suggests that each patient’s behavioral deficit can be specifically treated. However, even if the importance of indexing cognitive disturbances is well-established in psychiatric clinical settings, the manner with which to efficiently perform cognitive analyses is a matter of debate. This is mainly due to cognition fractionation, which means that a global assessment of all cognitive functions may take several hours to perform, and this is incompatible with both patients’ statuses and consultation pressures. Nevertheless, ERP analysis is non-invasive, painless, and cheap. In addition, ERPs provide the most informative profile for psychiatrists regarding the cognitive deficits presented by their patients, especially when examining ERP components that are well-characterized in terms of eliciting stimuli, technical recording methods, and quantification. These defined ERPs are easily implementable in clinical practice and are operationally related to the neurocognitive processes they reflect.Citation73

We would especially like to emphasize that the most useful components span different stages of the information processing stream, including P50, mismatch negativity (MMN), P300, NoGo P300, and error-related negativity (ERN). The P50 component is the earliest to be observed (around 50 ms) and the smallest in amplitude of the auditory ERPs. The P50 sensory gating effect refers to an amplitude reduction in P50 upon exposure to a second stimulus in a pair of identical stimuli presented with a short inter-stimulus interval. P50 gating is one of the earliest, measurable brain sensory processing steps that are linked to screening-out and attention filtering mechanisms of redundant incoming information.Citation74 MMN (also called N2a) is an ERP component with peak latency around 150 ms after stimulus and maximal amplitude at the frontal scalp locations. MMN is usually evoked by a physically deviant auditory stimulus that occurs in a series of frequent standard stimuli. It is believed to reflect cortical information processing at the earliest level of the sensory cortex; however, recent findings suggest that the transient auditory sensory memory representation underlying the MMN is facilitated by a long-term memory representation of the corresponding stimulus.Citation75 The P300 component (or P3) is a long-lasting positive component that occurs between 300 and 700 ms after stimulation. P3 is thought to reflect premotor processes, such as short-term memory updating or cognitive closure mechanisms.Citation58 The NoGo P300 has been identified as one of the markers for response inhibition,Citation76 which involves the activation of the executive system of the frontal lobes.Citation77 The neural basis for this executive system is believed to be a distributed circuitry, which involves the following: the prefrontal areas and anterior cingulated gyrus;Citation78 the orbitofrontal cortex;Citation79 the ventral frontal regions;Citation80 the parietal, dorsal, and ventral prefrontal regions;Citation81 and the premotor and supplementary motor areas. Finally, ERN represents a neural measure of error processing that peaks 50 ms after subjects make mistakes. This component is linked to the subject’s ability to evaluate his actions as “worse than expected”, and constitutes a “learning signal” that can subsequently be used to adjust behavior.Citation82

It has been suggested that the analysis of a weighted combination of these electrophysiological features may provide greater diagnostic power than any single endophenotype alone.Citation83 For instance, Price et alCitation84 compared and contrasted four electrophysiological components, analyzing their covariance on a single cohort of schizophrenic patients, family members, and controls. Their findings revealed that the use of the electrophysiological battery provided novel information on the characteristics of the different groups. In particular, they highlighted the heterogeneity of electrophysiological features among the groups and demonstrated that the combined analysis could serve to minimize the impact of such heterogeneity.Citation84

We propose the use of P50, MMN, P300, NoGo P300, and ERN to facilitate the indexing of cognitive stages affected in psychiatric patients by assessing, respectively, the attention-filtering, early perceptive discriminative, response-related decisional, inhibitory, and self-action evaluation processes. Indeed, neurocognitive processes (indexing attention, executive functions, and meta-cognition) have been linked to psychopathology.Citation85 Once cognitive disturbances are characterized through ERP screening for individual patients, psychiatrists will be able to orient the “cognitive” treatment (individually or in groups that present homogeneous patterns of cognitive deficits). More precisely, specific cognitive retraining procedures could be used to target deficits and increase cognitive efficiency, which has already been shown to reduce clinical symptoms.Citation86,Citation87 In this regard, there are currently many CRPs available, including those directed at attention mechanisms (increasing or decreasing the attention resources devoted to a specific cue),Citation88 for which compelling evidence has already been gathered in anxiety disorders. Indeed, behavioral and ERP studies have shown that attention training can alter threat bias, influence vulnerability to stress, and reduce clinical anxiety symptoms by modulating top-down processes of attention control rather than processes of early attention orienting.Citation89 In the same vein, there are also available CRPs increasing organization, goal achievement,Citation90 cognitive control (ie, inhibitory skills),Citation46 and even self-monitoring.Citation91

Conclusion

Creating a multi-disciplinary approach to mental illness, including neurophysiologists and neuropsychologists

Mental illness is commonly managed with a combined approach involving psychotherapy and pharmacological intervention. This strategy is certainly useful for some patients, but the relapse rate remains tremendously high for several psychiatric disorders. Thus, in psychiatry there is currently a recognized need for alternatives to psychotherapy and medication.Citation11 Cognitive deficits have gained considerable importance in the field as critical features of mental illness.Citation21 Therefore, in the present paper, we suggest that a possible way to increase the efficiency of psychiatric treatment is to include ERPs and CRPs in clinical practice, combining these techniques with psychotherapy and medication. However, this would require a significant collaboration between psychiatry departments, clinical neurophysiology laboratories, and neuropsychological rehabilitation centers. In this view, a psychiatrist may prescribe a “complete ERP screening” to his/her patients, which is easy to perform and will not be time-consuming if only the main cognitive domains are analyzed (attention, execution, and self-monitoring). The basic purpose of these ERP screening tests will be to indicate the likelihood of genuine cognitive impairment, which can be inferred through the comparison of the patient’s results with reference controls. Thus, a borderline score or a very impaired score (along with supporting history) might lead the psychiatrist to order a more specialized assessment of cognition (eg, by neuropsychologists), and thus thoroughly identify which cognitive domain(s) to rehabilitate. Indeed, CRPs have been proven to have a positive impact on daily quality of lifeCitation92 and on clinical symptoms.Citation86,Citation87 Hence, psychiatric treatment data from neurophysiologists (ERPs) could help neuropsychologists decide which cognitive processes to rehabilitate through CRPs in order to enhance the daily quality of life and soften the clinical symptoms of individual patients. Ultimately, based on the fact that the long-lasting, positive effects of CRPs on clinical symptoms have already been demonstrated,Citation35,Citation87 we are convinced that the combination of this cognitive procedure (involving ERPs and CRPs) with psychotherapy and medication could lead to decreased relapse rates.

There is still a long way to go before this strategy can be implemented into daily clinical practice

Although the rationale of this proposal is highly reliable and theoretically grounded, we are entirely aware that it is currently impossible to implement this proposal in clinical practice. Indeed, the principal concern relates to the ERP screening procedure. To date, the majority of ERP related studies comparing psychiatric populations to matched controls used grand-averaged data (ie, mean data comparing a group of healthy individuals to a group of patients). However, in daily clinical practice, in order to be able to decide whether an individual patient presents a genuine cognitive impairment, we need to develop normal and impaired ranges for ERP parameters (amplitude and/or latency). In other words, it is necessary to accumulate unambiguous referenced normative data in order to determine whether a patient requires cognitive rehabilitation. In this regard, there already exist guidelines for some ERP components (MMN and P300), which could be clinically implemented.Citation93 For other components, normative data remains to be gathered (P50, NoGo P300, and ERN). Therefore, there is an urgent need for further research to develop multisite guidelines that can be compared and used across studies by recording a battery of these five electrophysiological measures (P50, MMN, P300, NoGo P300, and ERN).

We propose that the time needed for ERP screening could be greatly reduced by focusing on the five ERP components described above, while other components (eg, contingent negative variation, P100, N300, and N400) and other related cognitive processes (eg, anticipation effects, visual, emotional, or language processes) may be of great interest. Here, we have focused on the components related to attention (through MMN, P50), execution (NoGo P300), memory and decision-making capacity (P300), and self-monitoring (ERN), which are the ones that have been primarily screened in psychopathological states.Citation85 Nevertheless, if our approach proves to be efficient, other batteries using different components could also be developed for future clinical use.

To conclude, there is a general agreement that a multi-disciplinary approach is required for the successful treatment of mental illness. In this proposal, we have suggested that psychiatrists should continue to maintain their classic collaboration with psychologists, who are trained to provide psychotherapy. However, we now suggest that neurophysiologists and neuropsychologists may be crucial to aid psychiatrists in the identification of cognitive processes that should be rehabilitated on a patient-by-patient basis. The resulting combined approach (ie, medication, psychotherapy, and “ERP-oriented cognitive rehabilitation”) should reduce relapse rates for many psychiatric afflictions, because individual cognitive interventions would be specifically targeted based on each patient’s needs, thus providing an “individualized” or “personalized” medicine. Therefore, the challenge of future studies will be to highlight whether this procedure is efficient enough to be incorporated into a psychiatrist’s current treatment method toolbox.

Acknowledgments

Salvatore Campanella is a Research Associate at the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS, Belgium).

Disclosure

This research was funded by the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS, Belgium), but this did not exert any editorial direction or censorship on any part of this article. The author reports no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PrinceMPatelVSaxenaSNo health without mental healthLancet2007370959085987717804063

- BascoMBosticJDaviesDMethods to Improve Diagnostic Accuracy in a Community Mental Health SettingAm J Psychiatry20001571599160511007713

- EpsteinJSternESilbersweigDNeuropsychiatry at the millenium: the potential for mind/brain integration through emerging interdisciplinary research strategiesClin Neurosci Res200111018

- KohnRSaxenaSLevavISaracenoBThe treatment gap in mental health careBull World Health Organ2004821185886615640922

- PerryATarrierNMorrissRMcCarthyELimbKRandomised controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatmentBMJ199931871771491539888904

- RobinsonDWoernerMGAlvirJMPredictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorderArch Gen Psychiatry199956324124710078501

- AndreasenNCCarpenterWTKaneJMLasserRAMarderSRWeinbergerDRRemission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensusAm J Psychiatry2005162344144915741458

- BoothbyLADoeringPLAcamprosate for the treatment of alcohol dependenceClin Ther200527669571416117977

- HollonSDThaseMEMarkowitzJCTreatment and prevention of depressionPsychol Science20023139

- LeuchtSBarnesTRKisslingWEngelRRCorrellCKaneJMRelapse prevention in schizophrenia with new-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trialsAm J Psychiatry200316071209122212832232

- DobsonKSHollonSDDimidjianSRandomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the prevention of relapse and recurrence in major depressionJ Consult Clin Psychol200876346847718540740

- HenggelerSWMultisystemic Therapy: An overview of clinical procedures, outcomes, and policy implicationsChild Psychol Psychiatry Rev199941110

- PikeKMWalshBTVitousekKWilsonGTBauerJCognitive behavior therapy in the posthospitalization treatment of anorexia nervosaAm J Psychiatry2003160112046204914594754

- ChiesaASerrettiAMindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysisPsychiatry Res2011187344145320846726

- LeshnerAIAddiction is a brain disease, and it mattersScience1997278533545479311924

- PogarellOHegerlUBoutrosNClinical neurophysiology services in psychiatry departmentsPsychiatr Serv200556787116020824

- SlotemaCWBlomJDHoekHWSommerIEShould we expand the toolbox of psychiatric treatment methods to include Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)? A meta-analysis of the efficacy of rTMS in psychiatric disordersJ Clin Psychiatry201071787388420361902

- LioumisPKicićDSavolainenPMäkeläJPKähkönenSReproducibility of TMS-Evoked EEG responsesHum Brain Mapp20093041387139618537115

- McClintockSMFreitasCObermanLLisanbySHPascual-LeoneATranscranial magnetic stimulation: a neuroscientific probe of cortical function in schizophreniaBiol Psychiatry2011701192721571254

- FerrarelliFMassiminiMPetersonMJReduced evoked gamma oscillations in the frontal cortex in schizophrenia patients: a TMS/EEG studyAm J Psychiatry20081658996100518483133

- LarøiFRaballoANotes from Underground: Are Cognitive-Enhancing Drugs Respecting their Promises?Front Psychol2010115821833224

- HeinrichsRWZakzanisKKNeurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidenceNeuropsychology19981234264459673998

- RobinsonLJThompsonJMGallagherPA meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorderJ Affect Disord2006931–310511516677713

- LoeberSVollstädt-KleinSvon der GoltzCFlorHMannKKieferFAttentional bias in alcohol-dependent patients: the role of chronicity and executive functioningAddict Biol200914219420319291010

- CastellanosFXSonuga-BarkeEJMilhamMPTannockRCharacterizing cognition in ADHD: beyond executive dysfunctionTrends Cogn Sci200610311712316460990

- HeatonRKGladsjoJAPalmerBWKuckJMarcotteTDJesteDVStability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophreniaArch Gen Psychiatry2001581243211146755

- GoldJMCognitive deficits as treatment targets in schizophreniaSchizophr Res2004721212815531404

- BarkNRevheimNHuqFKhalderovVGanzZWMedaliaAThe impact of cognitive remediation on psychiatric symptoms of schizophreniaSchizophr Res200363322923512957702

- SpauldingWDFlemingSKReedDSullivanMStorzbachDLamMCognitive functioning in schizophrenia: implications for psychiatric rehabilitationSchizophr Bull199925227528910416731

- MedaliaARichardsonRWhat predicts a good response to cognitive remediation interventions?Schizophr Bull200531494295316120830

- LambHRA century and a half of psychiatric rehabilitation in the United StatesNew Dir Ment Health Serv20019911011496513

- AllenDNGoldsteinGSeatonBECognitive rehabilitation of chronic alcohol abusersNeuropsychol Rev19977121399243529

- HogartyGEFlesherSUlrichRCognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behaviorArch Gen Psychiatry200461986687615351765

- WykesTReederCWilliamsCCornerJRiceCEverittBAre the effects of cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) durable? Results from an exploratory trial in schizophreniaSchizophr Res2003612–316317412729868

- LevauxMNLaroiFOfferlin-MeyerIDanionJMVan der LindenMThe Effectiveness of the Attention Training Technique in Reducing Intrusive Thoughts in Schizophrenia: A Case StudyClin Case Stud2011106466484

- MedaliaAChoiJCognitive remediation in schizophreniaNeuropsychol Rev200919335336419444614

- KurtzMMMobergPJGurRCGurREApproaches to cognitive remediation of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysisNeuropsychol Rev200111419721011883669

- SuslowTSchonauerKAroltVAttention training in the cognitive rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients: a review of efficacy studiesActa Psychiatr Scand20011031152311202123

- KrabbendamLAlemanACognitive rehabilitation in schizophrenia: a quantitative analysis of controlled studiesPsychopharmacology (Berl)20031693–437638212545330

- TwamleyEWJesteDVBellackASA review of cognitive training in schizophreniaSchizophr Bull200329235938214552510

- McGurkSRTwamleyEWSitzerDIMcHugoGJMueserKTA meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophreniaAm J Psychiatry2007164121791180218056233

- PillingSBebbingtonPKuipersEPsychological treatments in schizophrenia: II. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of social skills training and cognitive remediationPsychol Med200232578379112171373

- ElgamalSMcKinnonMCRamakrishnanKJoffeRTMacQueenGSuccessful computer-assisted cognitive remediation therapy in patients with unipolar depression: a proof of principle studyPsychol Med20073791229123817610766

- HofmannSGCognitive mediation of treatment change in social phobiaJ Consult Clin Psychol200472339339915279523

- VirtaMVedenpääAGrönroosNAdults with ADHD benefit from cognitive-behaviorally oriented group rehabilitation: a study of 29 participantsJ Atten Disord200812321822618192618

- WiersRWEberlCRinckMBeckerESLindenmeyerJRetraining automatic action tendencies changes alcoholic patients’ approach bias for alcohol and improves treatment outcomePsychol Sci201122449049721389338

- KremenWSSeidmanLJFaraoneSVToomeyRTsuangMTThe paradox of normal neuropsychological function in schizophreniaJ Abnorm Psychol2000109474375211196000

- RuffRMA friendly critique of neuropsychology: facing the challenges of our futureArch Clin Neuropsychol200318884786414609580

- ChanRCShumDToulopoulouTChenEYAssessment of executive functions: review of instruments and identification of critical issuesArch Clin Neuropsychol200823220121618096360

- CullenBO’NeillBEvansJJCoenRFLawlorBAA review of screening tests for cognitive impairmentJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200778879079917178826

- BruceVYoungAUnderstanding face recognitionBr J Psychol198677Pt 33053273756376

- HaxbyJVHoffmanEAGobbiniMIThe distributed human neural system for face perceptionTrends Cogn Sci20004622323310827445

- KasparekTHow and why psychiatrists should use imaging methodsActiv Nerv Super2010523–4118127

- GreiciusMResting-state functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disordersCurr Opin Neurol200821442443018607202

- CalhounVDAdaliTPearlsonGDKiehlKANeuronal chronometry of target detection: fusion of hemodynamic and event-related potential dataNeuroimage200630254455316246587

- RuggMDColesMGHElectrophysiology of Mind Event-Related Brain Potentials and CognitionOxfordOxford University Press, Oxford Psychology Series1995

- CampanellaSPetitGMauragePKornreichCVerbanckPNoëlXChronic alcoholism: insights from neurophysiologyNeurophysiol Clin2009394–519120719853791

- CampanellaSGueritJMHow clinical neurophysiology may contribute to the understanding of a psychiatric disease such as schizophreniaNeurophysiol Clin2009391313919268845

- CampanellaSPogarellOBoutrosNEvent-related potentials in substance use disorders: A narrative review based on papers from 1984 to 2012Clin EEG Neurosci Available from: http://eeg.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/10/07/1550059413495533.abstractAccessed November 6, 2013

- SuttonSTuetingPZubinJJohnERInformation delivery and the sensory evoked potentialScience19671553768143614396018511

- PolichJUpdating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3bClin Neurophysiol2007118102128214817573239

- HansenneMEvent-related brain potentials in psychopathology: clinical and cognitive perspectivesPsychologica Belgica2006461–2536

- PowerMDalgleishTCognition and Emotion: From Order to DisorderHovePsychology Press1997

- CampanellaSGaspardCDebatisseDBruyerRCrommelinckMGueritJMDiscrimination of emotional facial expressions in a visual oddball task: an ERP studyBiol Psychol200259317118612009560

- CampanellaSPhilippotPInsights from ERPs into emotional disorders: an affective neuroscience perspectivePsychologica Belgica2006461–23753

- CampanellaSMontedoroCStreelEVerbanckPRosierVEarly visual components (P100, N170) are disrupted in chronic schizophrenic patients: an event-related potentials studyNeurophysiol Clin2006362717816844545

- MauragePPhilippotPVerbanckPIs the P300 deficit in alcoholism associated with early visual impairments (P100, N170)? An oddball paradigmClin Neurophysiol2007118363364417208045

- MauragePCampanellaSPhilippotPAlcoholism leads to early perceptive alterations, independently of comorbid depressed state: an ERP studyNeurophysiol Clin2008382839718423329

- MejiasSRossignolMDebatisseDEvent-related potentials (ERPs) in ecstasy (MDMA) users during a visual oddball taskBiol Psychol200569333335215925034

- RossignolMPhilippotPDouilliezCCrommelinckMCampanellaSThe perception of fearful and happy facial expression is modulated by anxiety: an event-related potential studyNeurosci Lett2005377211512015740848

- RossignolMCampanellaSMauragePHeerenAFalboLPhilippotPEnhanced perceptual responses during visual processing of facial stimuli in young socially anxious individualsNeurosci Lett20125261687322884932

- RossignolMCampanellaSBissotCPhilippotPFear of negative evaluation and attentional bias for facial expressions: an event-related studyBrain Cogn201382334435223811212

- PfefferbaumARothWTFordJMEvent-related potentials in the study of psychiatric disordersArch Gen Psychiatry19955275595637598632

- AdlerLEPachtmanEFranksRDPecevichMWaldoMCFreedmanRNeurophysiological evidence for a defect in neuronal mechanisms involved in sensory gating in schizophreniaBiol Psychiatry19821766396547104417

- NäätänenRKujalaTEsceraCThe mismatch negativity (MMN) – a unique window to disturbed central auditory processing in ageing and different clinical conditionsClin Neurophysiol2012123342445822169062

- SmithJLJohnstoneSJBarryRJEffects of pre-stimulus processing on subsequent events in a warned Go/NoGo paradigm: response preparation, execution and inhibitionInt J Psychophysiol200661212113316214250

- KaiserSUngerJKieferMMarkelaJMundtCWeisbrodMExecutive control deficit in depression: event-related potentials in a Go/Nogo taskPsychiatry Res2003122316918412694891

- PosnerMIDiGirolamoGJExecutive attention: confict, target detection and cognitive controlParasuramanRThe Attentive BrainCambridgeMIT Press1998401423

- FusterJMThe Prefrontal Cortex: Anatomy, Physiology and Neuropsychology of the Frontal Lobe2nd edNew YorkRaven Press1989

- BrownGGKindermannSSSiegleGJGranholmEWongECBuxtonRBBrain activation and pupil response during covert performance of the Stroop Color Word taskJ Int Neuropsychol Soc19995430831910349294

- WatanabeJSugiuraMSatoKThe human prefrontal and parietal association cortices are involved in NO-GO performances: an event-related fMRI studyNeuroimage20021731207121612414261

- HolroydCBColesMGThe neural basis of human error processing: reinforcement learning, dopamine, and the error-related negativityPsychol Rev2002109467970912374324

- CalkinsMEIaconoWGEye movement dysfunction in schizophrenia: a heritable characteristic for enhancing phenotype definitionAm J Med Genet2000971727610813807

- PriceGWMichiePTJohnstonJA multivariate electrophysiological endophenotype, from a unitary cohort, shows greater research utility than any single feature in the Western Australian family study of schizophreniaBiol Psychiatry200660111016368076

- GreenMFNuechterleinKHGoldJMApproaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: the NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteriaBiol Psychiatry200456530130715336511

- LecardeurLStipEGiguereMBlouinGRodriguezJPChampagne-LavauMEffects of cognitive remediation therapies on psychotic symptoms and cognitive complaints in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a randomized studySchizophr Res20091111–315315819395240

- ParkSPüschelJSauterBHRentschMHellDSpatial working memory deficits and clinical symptoms in schizophrenia: a 4-month follow-up studyBiol Psychiatry199946339240010435205

- AmirNWeberGBeardCBomyeaJTaylorCTThe effect of a single-session attention modification program on response to a public-speaking challenge in socially anxious individualsJ Abnorm Psychol2008117486086819025232

- EldarSBar-HaimYNeural plasticity in response to attention training in anxietyPsychol Med201040466767719627649

- LevineBRobertsonIHClareLRehabilitation of executive functioning: an experimental-clinical validation of goal management trainingJ Int Neuropsychol Soc20006329931210824502

- AldermanNFryRKYoungsonHAImprovement of self-monitoring skills, reduction of behaviour disturbance and the dysexecutive syndrome: comparison of response cost and a new programme of self-monitoring trainingNeuropsychol Rehabilit19955193221

- UeokaYTomotakeMTanakaTQuality of life and cognitive dysfunction in people with schizophreniaProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry2011351535920804809

- DuncanCCBarryRJConnollyJFEvent-related potentials in clinical research: guidelines for eliciting, recording, and quantifying mismatch negativity, P300, and N400Clin Neurophysiol2009120111883190819796989

- MauragePPesentiMPhilippotPJoassinFCampanellaSLatent deleterious effects of binge drinking over a short period of time revealed only by electrophysiological measuresJ Psychiatry Neurosci20093411111819270761

- MauragePCampanellaSPhilippotPVermeulenNConstantELuminetOde TimaryPElectrophysiological correlates of the disrupted processing of anger in alcoholismInt J Psychophysiol2008701506218577404