Abstract

We aimed to evaluate the functional abilities of persons with Rett syndrome (RTT) in stages III and IV. The group consisted of 60 females who had been diagnosed with RTT: 38 in stage III, mean age (years) of 9.14, with a standard deviation of 5.84 (minimum 2.2/maximum 26.4); and 22 in stage IV, mean age of 12.45, with a standard deviation of 6.17 (minimum 5.3/maximum 26.9). The evaluation was made using the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory, which has 197 items in the areas of self-care, mobility, and social function. The results showed that in the area of self-care, stage III and stage IV RTT persons had a level of 24.12 and 18.36 (P=0.002), respectively. In the area of mobility, stage III had 37.22 and stage IV had 14.64 (P<0.001), while in the area of social function, stage III had 17.72 and stage IV had 12.14 (P=0.016). In conclusion, although persons with stage III RTT have better functional abilities when compared with stage IV, the areas of mobility, self-care, and social function are quite affected, which shows a great functional dependency and need for help in basic activities of daily life.

Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a chronic and incapacitating condition that has distinct phenotypic characteristics. It is a neurological disorder characterized by cognitive impairments, communicative dysfunctions, stereotyped movements, and changes in growth.Citation1,Citation2 Its genetic identification was described in 1999 as an alteration in the MECP2 gene,Citation3 but the first characterization was established in 1966 by the Austrian physician Andreas Rett,Citation4 who reported observations of girls who demonstrated autistic behavior, dementia, apraxia of gait, stereotypic hand movements, and loss of facial expression.Citation5,Citation6 The diagnosis of RTT is based on clinical criteriaCitation7 established by Hagberg et alCitation8 and subsequently updated by Hagberg et alCitation9 and reviewed by Neul et al.Citation10

RTT almost exclusively affects girls,Citation11 who show no abnormalities at birth or in the first months of life. However, between 6 and 18 months of age, RTT sufferers display regression of developmental milestones, irritability, and stagnation in neuromotor development.Citation12,Citation13 Other characteristic problems include a loss of functional abilities, with symptoms of seizures,Citation14–Citation16 characteristics of autism, and autonomic dysfunctionCitation17 with the prognosis of severe cognitive impairment.Citation18

The characteristic clinical pattern and profile of RTT over time was illustrated in the system of four clinical stages.Citation19 This system still remains useful for the description of the classical form of the disease:Citation20 stage I (stagnation) – early onset stagnation stage at 6 months to 1.5 years, which includes developmental arrest, decelerating head growth, reduced communication and eye contact, and diminishing interest in play; stage II (regression) – the rapid destructive stage, at 1 year to 3 years with developmental deterioration, autistic features and stereotypies, severe dementia with loss of speech, and loss of hand skills with frequent hand wringing; stage III (pseudo-stationary stage) – contains some stabilization at preschool to school years, but exhibits gait ataxia, stereotypic hand movements, severe mental retardation or dementia, and epileptic seizures, and; stage IV (late motor deterioration) – the girls have decreased mobility around the age of 15 years and are often wheelchair-bound with persistent growth retardation. Scoliosis is also very common, emotional contact tends to be improved, and epilepsy becomes less common and more easily controlled.Citation20

Although the characteristics of the four stages of RTT are well presented and documented,Citation19,Citation20 a comparison between functional stages using an evaluation system that measures different functional areas is important for the understanding of capabilities in different everyday activities and also for monitoring disease progression. Due to the difficulty of early diagnosis and rapid passage through stages I and IICitation7,Citation9,Citation10 it is difficult to collect data in the early stages of the disease. However, the later stages (III and IV) persist for several years and enable scientific study.

For professionals in rehabilitation, RTT is a particularly challenging condition with respect to the severity of motor and cognitive impairment, the osteotendinous retractions, and progressive immobility, which characterize the later stages of the disease. In addition to professionals and family members, society needs information about the capabilities of people with RTT and the changes that occur at different stages. Lim et alCitation21 conducted a qualitative study exploring the daily experiences of families caring for children with RTT and found participants reporting a lack of education and rehabilitation and support services available to them. Those families reported that limited access to information reduced families’ capacity to adequately meet the needs of their child.

An interesting factor to assist in clinical practice is the development of studies that quantify the abilities of persons with RTT, which enables the verification of the true extent of capacities that will help to inform families, community, and appropriate interventions. It is important to present key information for clinicians and families regarding possible skill areas that may guide therapeutic interventions.Citation22

To date, a growing number of studies have revealed a variety of RTT characteristics including pathogenetical mechanisms,Citation23–Citation26 physiological characteristics,Citation27 polysomnographic abnormalities,Citation28 microvascular abnormalities,Citation29 seizures,Citation30,Citation31 bone abnormalities,Citation32–Citation35 oxidative stress,Citation36 and nutritional factors.Citation37,Citation38 However, considering the importance of functionality, few studies have aimed to quantify the different functional abilities of RTT persons. Larsson et alCitation39 made a description of early development; Downs et alCitation40 used observations for hand function; Baptista et alCitation41 as well as Djukic and McDermottCitation42 examined the pattern of visual fixation and social preferences using eyetracking technology. Marschik et alCitation43,Citation44 delineated the achievement of early speech-language milestones in RTT. Lotan et alCitation45 investigated a physical exercise program with a treadmill in RTT in order to improve functional skills, and Foley et alCitation22 used video data to investigate the course of gross motor function in girls and women with RTT. Finally, Lane et alCitation46 described the impact of clinical severity on quality of life among female children and adolescents with classic RTT and found that quality of life is significantly related to clinical severity, as they also examined the relationships among MECP2 mutations, clinical severity, and psychosocial and physical aspects of quality of life for persons with RTT.

Furthermore, improved understanding on the motor and cognitive capacity of RTT is particularly important for professionals in rehabilitation, in view of the impact of RTT on the level of functional independence of these persons.

Therefore, in order to provide detailed knowledge of the functional abilities of people with RTT, in the current study we aimed to characterize and identify areas of greater functional abilities and verify functional differences between persons at stages III and IV of RTT.

Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee for review of research projects of the Hospital of Clinics of the School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo under protocol number 1033/03 and informed consent was obtained from the parents of the persons with RTT.

Participants

We evaluated 60 persons with RTT, who met the criteria for classic or typical form of the disease; 38 persons were in stage III, mean age (years) of 9.14 with a standard deviation of 5.84 (minimum 2.2/maximum 26.4) and 22 persons were in stage IV, mean age of 12.45 with a standard deviation of 6.17 (minimum 5.3/maximum 26.9). These stages were chosen for evaluation because early stages of the disease (stage I and II) persist briefly with rapid progression, making them particularly difficult to monitor and diagnose.

The participants were a consecutive selection of persons with RTT, consisting of a convenience sample determined by availability. Parental permission to conduct the study was obtained from every parent by signing a consent form. Participant’s parents needed to be available to answer the necessary items with the simultaneous presence of their children.

Of the 60 classifications and evaluations, 40 (67%) were performed at the outpatient clinic of the pediatric neurology department of the University of São Paulo and 20 (33%) were performed at the Brazilian Rett Syndrome Association. The diagnosis and classifications as used by Larsson et alCitation47 and Halbach et alCitation48 were made by a group of child neurologists of the participating institutions with experience in RTT, and who had been following the clinical treatments and therapeutic interventions of most of the participants for several years.

Instrument

The Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI) was used to verify functional difficulties. The PEDI was developed by Haley et alCitation49 and translated, validated, and adapted to address the specificities of the sociocultural environment in Brazil, by Mancini,Citation50 with permission and collaboration of the authors of the original assessment. Psychometric properties of the PEDI (Brazilian version) suggested high inter-interviewer reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient: 0.91 to 0.99) and excellent intrarater reliability (Pearson’s correlation: 0.89 to 0.98)Citation50 and it was used in several earlier studies.Citation51–Citation54

The main purpose of this assessment instrument is to collect information about capacity and performance in the areas of self-care, mobility, and social function. The age at which more than 90% of children were able to perform a particular activity is determined and validated. It is expected that over 90% of typical developing children are able to perform all activities of the PEDI after 8 years of age.

Procedures

To investigate functional abilities, 73 self-care, 59 mobility, and 65 social function activities (total of 197) were assessed, for which the person was considered able (1) or unable (0) to perform the activity. For administering the PEDI, prior minimal training, as recommended by the authors,Citation49 was conducted. Although the PEDI can be applied without the presence of the person, this study employed the method of interviewing the parents concurrent to direct observation of all persons with RTT.

All interviews were held in the assessment room of the participating institutions. Most interviews were conducted with the presence of the mother of the participants (n=54; 90%) or with the father and mother together (n=5; 10%). In the case of disagreement (only in a few occasions) agreement by discussion among parents and the evaluator was necessary to score a response.

Data analysis

The results of functional abilities were assessed by transforming the raw score into a continuous score as used by Öhrvall et al.Citation55 This continuous score data allows the use of the PEDI data for people under and over the age of 8 years. In addition, using the continuous score made it possible to perform comparisons between the areas of self-care, mobility, and social function of the PEDI functional skills that feature a number of different activities.

To present capacity using the PEDI items to compare stage III and IV, values were weighted and organized according to age. An item was not considered valid if the person had not reached the age where certain functional abilities can be performed by at least 90% of children without any changes. For this reason, the number of items considered valid differed between children younger and children older than 8 years old.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the sample characteristics. A two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the scores obtained in the areas of mobility, self-care, and social function on each stage of RTT. By this means, the different areas (mobility, self-care, social function) were taken as within factor and the two stages (stage III and stage IV) were taken as between factor. Finally, the one-way ANOVA was used to compare the stages of RTT on each area of the PEDI. Effect sizes were calculated by dividing the mean change scores for each stage in all areas of the PEDI by the standard deviation of continuous scores. The interpretation of effect sizes are based on Cohen’s criteria, whereby an effect of less than 0.4 is considered small, 0.5 is considered moderate, and above 0.8 is considered large,Citation56 as used by Lin et alCitation57 and Tellegen and Sanders.Citation58 The SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data management and statistical analysis. Significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

The results of functional skills are presented through tables with presentation of functional skills that were executed by at least one of the persons with RTT, together with the age at which 90% of normal children are expected to be able to accomplish the task. Also appearing in these tables are the numbers of persons where the activity was not applicable due to age and the number and percentage of persons with stage III and IV RTT able and unable to perform the task.

Self-care

For the PEDI assessment of the 73 activities that make up the area of self-care, 52 (71.2%) were not performed by any of the persons, who had reached the age to do so. The worst performance in this area was zero and the best 19, with a mean score of 6.67±3.88. This value corresponds to only 9.1% of possible performance. The three functional activities that were more often achieved considering both stages were as follows. First: eats foods whipped/mashed/strained, 60 individuals – 38 (100%) stage III and 22 (100%) stage IV. Second: eats foods ground/granulated, 36 (95%) stage III and 19 (87%) stage IV. Third: for stage III, eats foods chopped/in pieces and eats foods of various textures, 45 individuals (75%); and for stage IV allows nose to be wiped, 14 individuals (64%). Thus, we can see that most of those functional activities are in the food texture subarea. The results of all functional tasks from the self-care assessment are presented in .

Table 1 Self-care activities performed by at least one person with Rett syndrome

Mobility

Eight of the 59 mobility activities (13.5%) evaluated were not performed by any person, despite the fact that they had reached the age to do so. The mean value of the raw score of mobility was 17.5±15.1, ranging from 1 to 44. This value corresponds to 30% of possible performance. The three functional activities that were more often achieved were as follows. First: sits if supported by equipment, 38 (100%) stage III and 22 (100%) stage IV. Second: sits in chair or bench unsupported, 35 (97%) stage III and 14 (64%) stage IV. Third: for stage III, moves within a room, but with difficulty, 34 (90%); and for stage IV, raises to sitting position in bed, eight (36%). The results of all functional mobility tasks are shown in .

Table 2 Mobility activities performed by at least one person with Rett syndrome

Social function

Of the 65 social function activities evaluated, 50 (76.9%) were not performed by any of the participants despite them reaching the age at which the average population would normally do so. The mean raw score of social function was 3.4±3.2, ranging from 0 to 14. This value corresponds to 5.2% of possible performance. The three functional activities that were achieved more often were as follows. First: orients to sound, 38 (100%) stage III and 22 (100%) stage IV. Second: shows awareness and interest in others, 21 (55%) stage III and six (27%) stage IV. Third: recognizes own name or name of familiar person, 18 (47%) stage III and six (27%) stage IV. The results of all social functional tasks are presented in .

Table 3 Social function activities performed by at least one person with Rett syndrome

Comparisons between the areas of self-care, mobility, and social function

The repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of the areas on the PEDI score (F2,116=43.20, P<0.001, partial η2=0.43) and a significant areas by stage interaction effect (F2,116=33.75, P<0.001, partial η2=037). Differences in scores between areas are noted (P<0.05) when areas are compared in stage III, but in stage IV there was no difference between the areas of mobility and social function ().

Table 4 Comparison between the different areas (indicated with P-values) of the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory for each stage of Rett syndrome

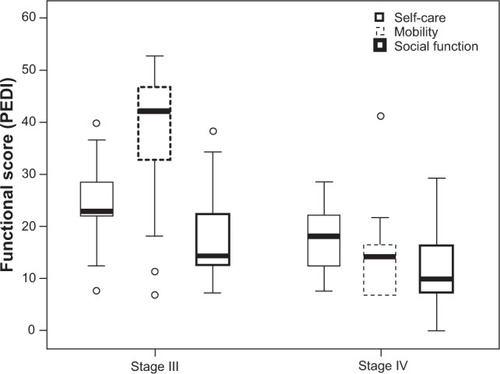

To present the comparisons between the areas of self-care, mobility, and social function with stages III and IV of the disease, box plot-type graphs were chosen (). The ANOVA one-way test was used for the comparison between stage III and stage IV in the area of self-care (F1,59=10.23; P<0.05, partial η2=0.15), mobility (F1,59=54.53; P<0.01, partial η2=0.48), and social function (F1,59=6,16; P<0.05, partial η2=0.10) of RTT. Significant differences were observed between the two groups of persons for all areas, indicating that persons with stage IV had the lowest scores.

Figure 1 Comparison of the three areas (self-care, mobility, and social function) between persons with stage III and stage IV Rett syndrome.

Abbreviation: PEDI, Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory.

Discussion

The functional abilities in RTT have gained much interest in the last decades.Citation2,Citation7,Citation40,Citation47 Results found in the literature concerning the outcomes in RTT studies vary greatly; some studies report high percentages for some abilities, while other studies find different results. Although some discrepancies in these studies may be found, they all show the general capacity of individuals with RTT. However, until now, comparable functional abilities in persons with stages III and IV of RTT have not been systematically investigated using instruments such as the PEDI. In the present study we therefore examined through questionnaires and direct observation the functional abilities of 60 people with stages III and IV RTT who presented functional abilities related to the areas of self-care, mobility, and social function.

A common area of self-care that greatly influences the inability of RTT persons is the difficulty to functionally move the hands.Citation2,Citation7 Appearance of stereotypies interferes with voluntary hand functions, such as rubbing, wringing, or clapping of both hands at the midline in front of the chest or around the mouth.Citation59–Citation61 In the current study, 26.7% of persons evaluated were able to eat with their fingers, 5.0% were able to use a spoon, 25.0% were able to hold a feeding bottle or cup with a spout, 15.0% were able to raise a glass to drink, and 3.4% were able to firmly raise a glass without a lid using both hands. Mount et alCitation62 observed in a series of 143 persons that 70.6% did not use hands with functional purpose. However, Fabio et alCitation63 found that the containment of manual stereotypies, postural control, and organization of external stimuli may be options for the functionality of RTT. Thus, while the area of self-care is fundamental to guarantee the basic conditions of daily living, the results show that RTT persons are unable to perform these basic living tasks, and therefore require a large amount of assistance from the family for most activities.

Considering mobility, persons with RTT who remain ambulant (stage III) have a characteristic gait, performed with the legs in extension and broadening the base of support. The steps are short and the hands remain clasped along the midline, with no reciprocal oscillation of the upper limbs. Sometimes, individuals in stage III RTT prefer to walk on tiptoe.Citation64 The lack of direction and planning gives the gait an apraxic character.Citation65 According to Segawa,Citation27,Citation66 who investigated 38 persons with RTT using an evaluation of the motor milestones, 47% were unable to walk outdoors without assistance. Colvin et alCitation67 found that 68% of 147 persons had never walked. Larsson et alCitation39 presented data on 119 persons evaluated, of whom 73% (87/119) learned to walk, but 20% stopped in the period of motor deterioration, others simply stopped walking, and of these, only 2% were able to relearn to walk.

In the current study, the PEDI was used to reveal different levels of ability in various functional abilities in mobility in RTT persons (). Considering walking and posture changes that are presented by a majority of the articles related to mobility in RTT, 29 (71%) of the persons in stage III were able to walk in internal or external environments and 30 (79%) were capable of purposely changing physical location with difficulty. The ability to walk is important for the RTT persons because they do not need to be constantly accompanied by a caregiver in in-house and controlled environments and are able to explore spaces and areas with little or no assistance. However, in outdoor environments people with RTT must be supported by a caregiver. Larsson et alCitation39 found that even girls and women who were able to walk were unable to perform or had difficulty performing ordinary transitional movements.

Lotan et alCitation45 investigated the feasibility of a physical exercise program with a treadmill for four persons with RTT (stage III) in order to promote fitness and health and showed statistically significant improvement in areas of functional ability such as knee walking, going up and down stairs, and walking at a speed over 25 m. Lifelong care for persons with RTT should include standing, weight bearing, and activity, since the majority of people with RTT today survive into adulthood.Citation47

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the transfer from a lying to a sitting position, and then maintenance of a sitting position, are the functional abilities that the persons in stage III and IV were most able to perform. An incentive to change simple posture provides functional benefits for RTT persons. Thus, achieving the sitting position adequately is fundamental for improving the quality of life of these persons, as it is a functional position that the person maintains throughout the day.

With respect to social function in RTT persons, the absence of speech with simple maintenance of vocalizations and babbling was observed. As verbal skills are quite limited,Citation2 attention is necessary to recognize nonverbal forms of communication. Forms of nonverbal communication are usually very subtle in RTT persons.Citation68

Marschik et al,Citation43,Citation44 in contrast to the commonly accepted concept that these children are normal in the preregression period, found markedly atypical development of speech-language capacities, suggesting a paradigm shift in the pathogenesis of RTT and a possible approach to its early detection.

In this study, we observed that four persons (11%) in stage III and only one person (5%) in stage IV used a single word with appropriate meaning and that ten persons (26%) in stage III and three (14%) in stage IV used meaningful gestures. SegawaCitation66 reported that 53% of 38 persons studied did not speak a word, and Halbach et alCitation48 in a longitudinal study about aging in RTT reported that 22% of 37 persons with RTT were at least sometimes able to express themselves by spoken language and/or signals. However, Larsson et alCitation39 reported 65% (75/115) of persons were able to, in some form, express what they wanted and Gratchev et alCitation69 reported that 34% of their 38 persons were able to pronounce a word. Although there are some differences in the reported findings with respect to speech in RTT persons, the difficulty of communication can be seen as a principal incapacity in RTT that hinders any social function. The inability to resolve problems along with difficulties in social interaction, self-protection, and community function are so great that total aid must be given by the caregiver for any basic needs.

The data in the current work indicate that the main difference between stage III and IV of RTT is in the area of mobility. Individuals in stage III have greater mobility than individuals in stage IV. These results appear to be expected, as the clinical stages of the disease indicate an increase in severity from stage I to stage IV. However, this is the first study that evaluates a significant number of persons with RTT using an evaluation system such as the PEDI, and through this assessment it is possible to discover important details in the areas of self-care, mobility, and social function. The knowledge of the capabilities of persons with RTT is important for organizing intervention programs and clarifying the functional abilities to families and the society.

The current study has several limitations worth noting. First, despite that the data fully represents the functional capabilities of the evaluated group, there are no studies on the validity and reliability of the PEDI in RTT, because this is the first study that uses the PEDI in this patient population. The second concern is in relation to the diagnostics and classification of RTT. Those data were obtained by a team of doctors, but unfortunately this study does not provide a MECP2-mutation diagnostic and classification division in stage IV (IVA and IVB). Moreover, RTT clinical assessment can generally contain errors in diagnostics and classification, which may have influenced some results. However, since all doctors involved are highly experienced we believe that this did not influence the results to a great extent. The third concern is the lack of data on different forms of therapy performed by patients, which can influence their performance in functional ability. We believe that future studies comparing therapies and functional abilities are relevant to the area. The fourth concern is the presence of outliers due to functional differences between people with RTT. The decision was made to keep the outliers in the results, even with the possibility of altering the mean and increasing variability.

Nevertheless, within the limits of these methodological caveats, the results presented here do allow for new insights into the functionality of persons with RTT. This study characterizes the functional abilities of stage III and IV RTT persons and shows differences between the two stages by using a standard international assessment that is used in different diseases. The use of the PEDI enables a verification of the real abilities of persons through the questionnaire and direct observation of persons, giving important data to professionals who work directly with RTT rehabilitation programs. The use of the PEDI also enables professionals to inform families about the difficulties and functional perspectives, providing a greater comprehension of the disease.

Conclusion

We suggest that the clinical features of RTT are indicative of a disabling disease, which leads to particular challenges for professionals working in rehabilitation. This conclusion is based on the finding that RTT severely impairs motor function due to the presence of scoliosis, osteotendinous retractions, and progressive immobility at the later stages of the disease (stage IV). In addition to motor impairment, cognitive changes are also evident in this population, and changes associated with musculoskeletal disorders may negatively impact the level of functional independence of individuals with RTT. Although persons with stage III RTT have better functional abilities when compared with stage IV, the areas of mobility, self-care, and social function are quite affected, which shows a great functional dependency and need for help in basic activities of daily life.

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support from FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) process number 2014/00320-8.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KirbyRSLaneJBChildersJLongevity in Rett Syndrome: analysis of the North American DatabaseJ Pediatr2010156113513819772971

- FehrSDownsJBebbingtonALeonardHAtypical presentations and specific genotypes are associated with a delay in diagnosis in females with Rett syndromeAm J Med Genet A2010152A102535254220815036

- AmirREVan Den VeyverIBWanMTranCQFranckeUZoghbiHYRett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2Nat Genet199923218518810508514

- RettAÜber ein eigenartiges hirnatrophisches Syndrom bei Hyperammonamie im Kindesalter. [On a unusual brain atrophy syndrome in hyperammonemia in childhood]Wien Medizin Wochschr196611637723726 German

- MonteggiaLMKavalaliETRett syndrome and the impact of MeCP2 associated transcriptional mechanisms on neurotransmissionBiol Psychiatry2009653020421019058783

- RettAThe mystery of the Rett syndromeBrain Dev199214supplS141S1421626626

- TemudoTSantosMRamosERett syndrome with and without detected MECP2 mutations: an attempt to redefine phenotypesBrain Dev2011331697620116947

- HagbergBGoutièresFHanefeldFRettAWilsonJRett syndrome: criteria for inclusion and exclusionBrain Dev1985733723734061772

- HagbergBHanefeldFPercyASkjeldalOAn update on clinically applicable diagnostic criteria in Rett syndromeEur J Pediatr Neurol200265293297

- NeulJLKaufmannWEGlazeDGRett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclatureAnn Neurol201068694495021154482

- HardwickSAReuterKWilliamsonSLDelineation of large deletions of the MeCP2 gene in Rett syndrome patients, including a familial case with a male probandEur J Hum Genet200715121218122917712354

- MorettiPZoghbiHYMeCP2 dysfunction in Rett syndrome and related disordersCurr Opin Genet Dev200616327628116647848

- MoserSJWeberPLütschgJRett syndrome: clinical and electrophysiologic aspectsPediatr Neurol20073629510017275660

- JianLNagarajanLde KlerkNPredictors of seizure onset in Rett syndromeJ Pediatr2006149454254717011329

- PintaudiMCalevoMGVignoliAEpilepsy in Rett syndrome: clinical and genetic featuresEpilepsy Behav201019329630020728410

- NissenkornAGakEVecslerMReznikHMenascuSBen ZeevBEpilepsy in Rett syndrome – the experience of a National Rett CenterEpilepsia20105171252125820491871

- ZoghbiHYRett syndrome: what do we know for sure?Nat Neurosci200912323924019238181

- MatsonJLDempseyTWilkinsJRett syndrome in adults with severe intellectual disability: exploration of behavioral characteristicsEur Psychiatry200823646046518207372

- HagbergBWitt-EngerströmIRett syndrome: a suggested staging system for describing impairment profile with increasing age towards adolescenceAm J Med Genet Suppl1986147593087203

- DunnHGImportance of Rett syndrome in child neurologyBrain Dev200123suppl 1S38S4311738840

- LimFDownsJLiJBaoXHLeonardHCaring for a child with severe intellectual disability in China: the example of Rett syndromeDisabil Rehabil201335434335122992162

- FoleyKRDownsJBebbingtonAChange in gross motor abilities of girls and women with rett syndrome over a 3- to 4-year periodJ Child Neurol201126101237124521636779

- GrilloELo RizzoCBianciardiLRevealing the complexity of a monogenic disease: rett syndrome exome sequencingPLoS One201382e5659923468869

- EliaMFalcoMFerriRCDKL5 mutations in boys with severe encephalopathy and early-onset intractable epilepsyNeurology2008711399799918809835

- PiniGBigoniSEngerströmIWVariant of Rett syndrome and CDKL5 gene: clinical and autonomic description of 10 casesNeuropediatrics2012431374322430159

- SignoriniCDe FeliceCDurandTIsoprostanes and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal: markers or mediators of disease? Focus on Rett syndrome as a model of autism spectrum disorderOxid Med Cell Longev2013201334382423844273

- SegawaMEarly motor disturbances in Rett syndrome and its pathophysiological importanceBrain Dev200527suppl 1S54S5816182486

- CarotenutoMEspositoMD’AnielloAPolysomnographic findings in Rett syndrome: a case-control studySleep Breath2013171939822392651

- BianciardiGAcampaMLambertiIMicrovascular abnormalities in Rett syndromeClin Hemorheol Microcirc201354110911323481597

- PrinceERingHCauses of learning disability and epilepsy: a reviewCurr Opin Neurol201124215415821293271

- DolceABen-ZeevBNaiduSKossoffEHRett syndrome and epilepsy: an update for child neurologistsPediatr Neurol201348533754523583050

- ZysmanLLotanMBen-ZeevBOsteoporosis in Rett syndrome: a study on normal valuesScientific World Journal200661619163017173180

- GonnelliSCaffarelliCHayekJBone ultrasonography at phalanxes in patients with Rett syndrome: a 3-year longitudinal studyBone200842473774218242156

- O’ConnorRDZayzafoonMFarach-CarsonMCSchanenNCMecp2 deficiency decreases bone formation and reduces bone volume in a rodent model of Rett syndromeBone200945234635619414073

- HofstaetterJGRoetzerKMKreplerPAltered bone matrix mineralization in a patient with Rett syndromeBone201047370170520601296

- De FeliceCSignoriniCLeonciniSThe role of oxidative stress in Rett syndrome: an overviewAnn N Y Acad Sci2012125912113522758644

- MotilKJBarrishJOLaneJVitamin D deficiency is prevalent in girls and women with Rett syndromeJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201153556957421637127

- MotilKJCaegEBarrishJOGastrointestinal and nutritional problems occur frequently throughout life in girls and women with Rett syndromeJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201255329229822331013

- LarssonGLindströmBWitt-EngerströmIRett syndrome from a family perspective: the Swedish Rett Center surveyBrain Dev200527suppl 1S14S1916182488

- DownsJBebbingtonAJacobyPLevel of purposeful hand function as a marker of clinical severity in Rett syndromeDev Med Child Neurol201052981782320345957

- BaptistaPMMercadanteMTMacedoECSchwartzmanJSCognitive performance in Rett syndrome girls: a pilot study using eyetracking technologyJ Intellect Disabil Res200650966266616901293

- DjukicAMcDermottMVSocial preferences in Rett syndromePediatr Neurol201246424024222490770

- MarschikPBKaufmannWEEinspielerCProfiling early socio-communicative development in five young girls with the preserved speech variant of Rett syndromeRes Dev Disabil20123361749175622699249

- MarschikPBKaufmannWESigafoosJChanging the perspective on early development of Rett syndromeRes Dev Disabil20133441236123923400005

- LotanMIsakovEMerrickJImproving functional skills and physical fitness in children with Rett syndromeJ Intellect Disabil Res200448873073515494062

- LaneJBLeeHSSmithLWClinical severity and quality of life in children and adolescents with Rett syndromeNeurology201177201812181822013176

- LarssonGJuluPOWitt-EngerströmISandlundMLindströmBNormal reactions to orthostatic stress in Rett syndromeRes Dev Disabil20133461897190523584170

- HalbachNSmeetsESteinbuschCMaaskantMvan WaardenburgDCurfsLAging in Rett syndrome: a longitudinal studyClin Genet201384322322923167724

- HaleySMCosterWJLudlowLHHaltiwangerJAndrellasPPediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI)BostonBoston University1992

- ManciniMCInventário de Avaliação Pediátrica de Incapacidade (PEDI). [Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory (PEDI).]Belo Horizonte, BrazilUFMG2005

- De Mello MonteiroCBAraujoDZSilvaTDQuantitative comparison of mobility and gross motor function in Brazilian children with cerebral palsyHealth Med20126724642470

- De Brito BrandãoMManciniMCVazDVPereira de MeloAPFonsecaSTAdapted version of constraint-induced movement therapy promotes functioning in children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trialClin Rehabil201024763964720530645

- GuaranyNRSchwartzIVGuaranyFCGiuglianiRFunctional capacity evaluation of patients with mucopolysaccharidosisJ Pediatr Rehabil Med201251374622543891

- MalheirosSRMonteiroCBMda SilvaTDFunctional capacity and assistance from the caregiver during daily activities in Brazilian children with cerebral palsyInt Arch Med201361123302576

- ÖhrvallAMEliassonACLöwingKÖdmanPKrumlinde-SundholmLSelf-care and mobility skills in children with cerebral palsy, related to their manual ability and gross motor function classificationsDev Med Child Neurol201052111048105520722662

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences2nd edHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum Associates1988

- LinKCChenHFChenCLValidity, responsiveness, minimal detectable change, and minimal clinically important change of the Pediatric Motor Activity Log in children with cerebral palsyRes Dev Disabil201233257057722119706

- TellegenCLSandersMRStepping Stones Triple P-Positive Parenting Program for children with disability: a systematic review and meta-analysisRes Dev Disabil20133451556157123475006

- NomuraYSegawaMMotor symptoms of the Rett syndrome: abnormal muscle tone, posture, locomotion and stereotyped movementBrain Dev199214supplS21S281626630

- HagbergBRett syndrome: clinical peculiarities, diagnostics approach, and possible causePediatr Neurol19895275832653342

- SegawaMNomuraYRett syndromeCurr Opin Neurol20051829710415791137

- MountRHCharmanTHastingsRPReillySCassHThe Rett syndrome behaviour questionnaire (RSBQ): refining the behavioural phenotype of Rett syndromeJ Child Psychol Psychiatr200243810991110

- FabioRAGiannatiempoSAntoniettiABuddenSThe role of stereotypies in overselectivity process in Rett syndromeRes Dev Disabil200930113614518359187

- LarssonGWitt-EngerströmIGross motor ability in Rett syndrome: the power of expectation, motivation and planningBrain Dev2001237781

- ArmstrongDDThe neuropathology of Rett syndromeBrain Dev199214supplS89S981626639

- SegawaMDiscussant: pathophysiologies of Rett syndromeBrain Dev200123suppl 1S218S22311738876

- ColvinLLeonardHKlerkNRefining the phenotype of common mutations in Rett syndromeJ Med Genet2004411253014729826

- KerrAMEarly clinical signs in the Rett disorderNeuropediatrics199426267717566455

- GratchevVVBashinaVMKlushnikTPUlasVUGorbachevskayaNLVorsanovaSGClinical, neurophysiological and immunological correlations in classical Rett syndromeBrain Dev200123suppl 1S108S11211738854